William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain from 1783 until the Acts of Union 1800 and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom from January 1801. He left office in March 1801, but served as prime minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806. He was also Chancellor of the Exchequer for all of his time as prime minister. He is known as "Pitt the Younger" to distinguish him from his father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, who had previously served as prime minister and is referred to as "William Pitt the Elder" (or "Chatham" by historians).

William Pitt | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by John Hoppner, c. 1804-06 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1804 – 23 January 1806 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Lord Grenville | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 January 1801 – 14 March 1801 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established Himself as Prime Minister of Great Britain | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Great Britain | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 December 1783 – 1 January 1801 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Duke of Portland | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Office abolished Himself as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1804 – 23 January 1806 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Lord Henry Petty | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 December 1783 – 1 January 1801 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Lord John Cavendish | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Henry Addington | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 July 1782 – 31 March 1783 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Lord John Cavendish | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Lord John Cavendish | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 28 May 1759 Hayes, Kent, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 23 January 1806 (aged 46) Putney, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham Lady Hester Grenville | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Cambridge | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||

Pitt's prime ministerial tenure, which came during the reign of King George III, was dominated by major political events in Europe, including the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Pitt, although often referred to as a Tory, or "new Tory", called himself an "independent Whig" and was generally opposed to the development of a strict partisan political system.

Pitt was regarded as an outstanding administrator who worked for efficiency and reform, bringing in a new generation of competent administrators. He increased taxes to pay for the great war against France and cracked down on radicalism. To engage the threat of Irish support for France, he engineered the Acts of Union 1800 and tried (but failed) to secure Catholic emancipation as part of the Union. He created the "new Toryism", which revived the Tory Party and enabled it to stay in power for the next quarter-century.

The historian Asa Briggs argues that his personality did not endear itself to the British mind, for Pitt was too solitary and too colourless, and too often exuded an attitude of superiority. His greatness came in the war with France. Pitt reacted to become what Lord Minto called "the Atlas of our reeling globe". William Wilberforce said, "For personal purity, disinterestedness and love of this country, I have never known his equal."[1] Historian Charles Petrie concludes that he was one of the greatest prime ministers "if on no other ground than that he enabled the country to pass from the old order to the new without any violent upheaval ... He understood the new Britain."[2] For this he is ranked highly amongst all British prime ministers in multiple surveys.[3][4]

Pitt served as prime minister for a total of eighteen years, 343 days, making him the second-longest serving British prime minister of all time, after Robert Walpole.

Early life

Family

William Pitt, the second son of William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, was born on 28 May 1759 at Hayes Place in the village of Hayes, Kent.[5] He was from a political family on both sides, as his mother, Hester Grenville, was sister of former prime minister George Grenville.[6] According to biographer John Ehrman, Pitt exhibited the brilliance and dynamism of his father's line, and the determined, methodical nature of the Grenvilles.[7]

Education

Suffering from occasional poor health as a boy, he was educated at home by the Reverend Edward Wilson. An intelligent child, Pitt quickly became proficient in Latin and Greek. He was admitted to Pembroke College, Cambridge, on 26 April 1773,[8] a month before turning fourteen. He studied political philosophy, classics, mathematics, trigonometry, chemistry and history.[9] At Cambridge, Pitt was tutored by George Pretyman, who became a close personal friend. Pitt later appointed Pretyman Bishop of Lincoln, then Winchester, and drew upon his advice throughout his political career.[10] While at Cambridge, he befriended the young William Wilberforce, who became a lifelong friend and political ally in Parliament.[11] Pitt tended to socialise only with fellow students and others already known to him, rarely venturing outside the university grounds. Yet he was described as charming and friendly. According to Wilberforce, Pitt had an exceptional wit along with an endearingly gentle sense of humour: "no man ... ever indulged more freely or happily in that playful facetiousness which gratifies all without wounding any."[12]

In 1776, Pitt, plagued by poor health, took advantage of a little-used privilege available only to the sons of noblemen, and chose to graduate without having to pass examinations. Pitt's father was said to have demanded him to continually translate aloud classical literature into English and declaim upon previously unknown topics in effort to develop his oratory skills.[13] Pitt's father, who had by then been raised to the peerage as Earl of Chatham, died in 1778. As a younger son, Pitt the Younger received only a small inheritance. He acquired his legal education at Lincoln's Inn and was called to the bar in the summer of 1780.[14]

Early political career

Member of Parliament

During the general elections of September 1780, at the age of 21, Pitt contested the University of Cambridge seat, but lost.[15] Still intent on entering Parliament, Pitt secured the patronage of James Lowther, later 1st Earl Lowther, with the help of his university friend, Charles Manners, 4th Duke of Rutland. Lowther effectively controlled the pocket borough of Appleby; a by-election in that constituency sent Pitt to the House of Commons in January 1781.[16] Pitt's entry into parliament is somewhat ironic as he later railed against the very same pocket and rotten boroughs that had given him his seat.[17]

In Parliament, the youthful Pitt cast aside his tendency to be withdrawn in public, emerging as a noted debater right from his maiden speech.[18] Pitt originally aligned himself with prominent Whigs such as Charles James Fox. With the Whigs, Pitt denounced the continuation of the American War of Independence, as his father strongly had. Instead he proposed that the prime minister, Lord North, make peace with the rebellious American colonies. Pitt also supported parliamentary reform measures, including a proposal that would have checked electoral corruption. He renewed his friendship with William Wilberforce, now MP for Hull, with whom he frequently met in the gallery of the House of Commons.[19]

Chancellorship

After Lord North's ministry collapsed in 1782, the Whig Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, was appointed prime minister. Pitt was offered the minor post of Vice-Treasurer of Ireland, but he refused, considering the post overly subordinate. Lord Rockingham died only three months after coming to power; he was succeeded by another Whig, William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne. Many Whigs who had formed a part of the Rockingham ministry, including Fox, now refused to serve under Lord Shelburne, the new prime minister. Pitt, however, was comfortable with Shelburne, and thus joined his government; he was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer.[20]

Fox, who became Pitt's lifelong political rival, then joined a coalition with Lord North, with whom he collaborated to bring about the defeat of the Shelburne administration. When Lord Shelburne resigned in 1783, King George III, who despised Fox, offered to appoint Pitt to the office of Prime Minister. But Pitt wisely declined, for he knew he would be incapable of securing the support of the House of Commons. The Fox–North coalition rose to power in a government nominally headed by William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland.[21]

Pitt, who had been stripped of his post as Chancellor of the Exchequer, joined the Opposition. He raised the issue of parliamentary reform in order to strain the uneasy Fox-North coalition, which included both supporters and detractors of reform. He did not advocate an expansion of the electoral franchise, but he did seek to address bribery and rotten boroughs. Though his proposal failed, many reformers in Parliament came to regard him as their leader, instead of Charles James Fox.

Effects of the American War of Independence

Losing the war and the Thirteen Colonies was a shock to the British system. The war revealed the limitations of Britain's fiscal-military state when it had powerful enemies and no allies, depended on extended and vulnerable transatlantic lines of communication, and was faced for the first time since the 17th century by both Protestant and Catholic foes. The defeat heightened dissension and escalated political antagonism to the King's ministers. Inside parliament, the primary concern changed from fears of an over-mighty monarch to the issues of representation, parliamentary reform, and government retrenchment. Reformers sought to destroy what they saw as widespread institutional corruption. The result was a crisis from 1776 to 1783. The peace in 1783 left France financially prostrate, while the British economy boomed due to the return of American business. That crisis ended in 1784 as a result of the King's shrewdness in outwitting Fox and renewed confidence in the system engendered by the leadership of Pitt. Historians conclude that the loss of the American colonies enabled Britain to deal with the French Revolution with more unity and organisation than would otherwise have been the case.[22] Britain turned towards Asia, the Pacific, and later Africa with subsequent exploration leading to the rise of the Second British Empire.[23]

First premiership

Rise to power

The Fox-North Coalition fell in December 1783, after Fox had introduced Edmund Burke's bill to reform the East India Company to gain the patronage he so greatly lacked while the King refused to support him. Fox stated the bill was necessary to save the company from bankruptcy. Pitt responded that: "Necessity is the plea for every infringement of human freedom. It is the argument of tyrants; it is the creed of slaves."[24] The King was opposed to the bill; when it passed in the House of Commons, he secured its defeat in the House of Lords by threatening to regard anyone who voted for it as his enemy. Following the bill's failure in the Upper House, George III dismissed the coalition government and finally entrusted the premiership to William Pitt, after having offered the position to him three times previously.[25]

Appointment

A constitutional crisis arose when the King dismissed the Fox-North coalition government and named Pitt to replace it. Though faced with a hostile majority in Parliament, Pitt was able to solidify his position within a few months. Some historians argue that his success was inevitable given the decisive importance of monarchical power; others argue that the King gambled on Pitt and that both would have failed but for a run of good fortune.[26]

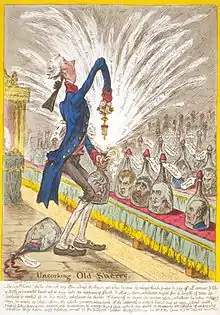

Pitt, at the age of 24, became Great Britain's youngest Prime Minister ever. The contemporary satire The Rolliad ridiculed him for his youth:[27]

Above the rest, majestically great,

Behold the infant Atlas of the state,

The matchless miracle of modern days,

In whom Britannia to the world displays

A sight to make surrounding nations stare;

A kingdom trusted to a school-boy's care.

Many saw Pitt as a stop-gap appointment until some more senior statesman took on the role. However, although it was widely predicted that the new "mince-pie administration" would not outlast the Christmas season,[28] it survived for seventeen years.[29]

So as to reduce the power of the Opposition, Pitt offered Charles James Fox and his allies posts in the Cabinet; Pitt's refusal to include Lord North, however, thwarted his efforts. The new government was immediately on the defensive and in January 1784 was defeated on a motion of no confidence. Pitt, however, took the unprecedented step of refusing to resign, despite this defeat. He retained the support of the King, who would not entrust the reins of power to the Fox–North Coalition. He also received the support of the House of Lords, which passed supportive motions, and many messages of support from the country at large, in the form of petitions approving of his appointment which influenced some Members to switch their support to Pitt. At the same time, he was granted the Freedom of the City of London. When he returned from the ceremony to mark this, men of the City pulled Pitt's coach home themselves, as a sign of respect. When passing a Whig club, the coach came under attack from a group of men who tried to assault Pitt. When news of this spread, it was assumed Fox and his associates had tried to bring down Pitt by any means.[30]

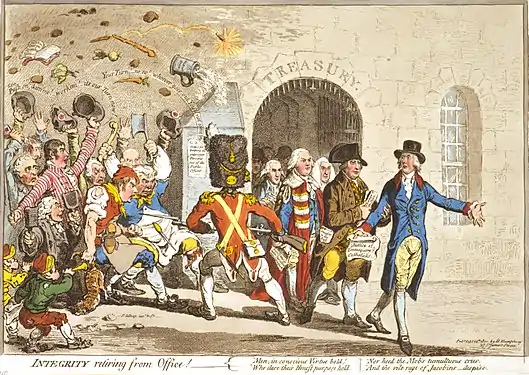

Electoral victory

Pitt gained great popularity with the public at large as "Honest Billy" who was seen as a refreshing change from the dishonesty, corruption and lack of principles widely associated with both Fox and North. Despite a series of defeats in the House of Commons, Pitt defiantly remained in office, watching the Coalition's majority shrink as some Members of Parliament left the Opposition to abstain.[30]

In March 1784, Parliament was dissolved, and a general election ensued. An electoral defeat for the government was out of the question because Pitt enjoyed the support of King George III. Patronage and bribes paid by the Treasury were normally expected to be enough to secure the government a comfortable majority in the House of Commons, but on this occasion, the government reaped much popular support as well.[31] In most popular constituencies, the election was fought between candidates clearly representing either Pitt or Fox and North. Early returns showed a massive swing to Pitt with the result that many Opposition Members who still had not faced election either defected, stood down, or made deals with their opponents to avoid expensive defeats.[32]

A notable exception came in Fox's own constituency of Westminster, which contained one of the largest electorates in the country. In a contest estimated to have cost a quarter of the total spending in the entire country, Fox bitterly fought against two Pittite candidates to secure one of the two seats for the constituency. Great legal wranglings ensued, including the examination of every single vote cast, which dragged on for more than a year. Meanwhile, Fox sat for the pocket borough of Tain Burghs. Many saw the dragging out of the result as being unduly vindictive on the part of Pitt and eventually the examinations were abandoned with Fox declared elected. Elsewhere, Pitt won a personal triumph when he was elected a Member for the University of Cambridge, a constituency he had long coveted and which he would continue to represent for the remainder of his life.[32]

First government

In domestic politics, Pitt concerned himself with the cause of parliamentary reform. In 1785, he introduced a bill to remove the representation of thirty-six rotten boroughs, and to extend, in a small way, the electoral franchise to more individuals.[33] Pitt's support for the bill, however, was not strong enough to prevent its defeat in the House of Commons.[34] The bill of 1785 was the last parliamentary reform proposal introduced by Pitt to British legislators.

Colonial reform

His administration secure, Pitt could begin to enact his agenda. His first major piece of legislation as prime minister was the India Act 1784, which re-organised the British East India Company and kept a watch over corruption. The India Act created a new Board of Control to oversee the affairs of the East India Company. It differed from Fox's failed India Bill 1783 and specified that the board would be appointed by the king.[35] Pitt was appointed, along with Lord Sydney, who was appointed President.[35] The act centralised British rule in India by reducing the power of the governors of Bombay and Madras and by increasing that of Governor-General Charles Cornwallis. Further augmentations and clarifications of the governor-general's authority were made in 1786, presumably by Lord Sydney, and presumably as a result of the company's setting up of Penang with their own superintendent (governor), Captain Francis Light, in 1786.

Convicts were originally transported to the Thirteen Colonies in North America, but after the American War of Independence ended in 1783, the newly formed United States refused to accept further convicts.[36] Pitt's government took the decision to settle what is now Australia and found the penal colony in August 1786. The First Fleet of 11 vessels carried over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts. The Colony of New South Wales was formally proclaimed by Governor Arthur Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney.[37]

Finances

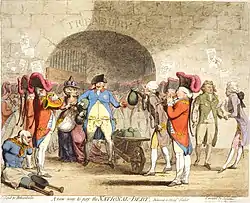

Another important domestic issue with which Pitt had to concern himself was the national debt, which had doubled to £243 million during the American war.[lower-alpha 1] Every year, a third of the budget of £24 million went to pay interest. Pitt sought to reduce the national debt by imposing new taxes. In 1786, he instituted a sinking fund so that £1 million a year was added to a fund so that it could accumulate interest; eventually, the money in the fund was to be used to pay off the national debt. By 1792, the debt had fallen to £170 million.[38][lower-alpha 2]

Pitt always paid careful attention to financial issues. A fifth of Britain's imports were smuggled in without paying taxes. He made it easier for honest merchants to import goods by lowering tariffs on easily smuggled items such as tea, wine, spirits, and tobacco. This policy raised customs revenues by nearly £2 million a year.[39][40][lower-alpha 3]

In 1797, Pitt was forced to protect the kingdom's gold reserves by preventing individuals from exchanging banknotes for gold. Great Britain would continue to use paper money for over two decades. Pitt was also forced to introduce Great Britain's first-ever income tax. The new tax helped offset losses in indirect tax revenue, which had been caused by a decline in trade.[41]

Foreign affairs

Pitt sought European alliances to restrict French influence, forming the Triple Alliance with Prussia and Holland in 1788.[42] During the Nootka Sound Controversy in 1790, Pitt took advantage of the alliance to force Spain to give up its claim to exclusive control over the western coast of North and South America. The Alliance, however, failed to produce any other important benefits for Great Britain.[43]

Pitt was alarmed at Russian expansion in the 1780s at the expense of the Ottoman Empire.[44] The relations between Russia and Britain were disturbed during the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 by Pitt's subscription to the view of the Prussian government that the Triple Alliance could not with impunity allow the balance of power in Eastern Europe to be disturbed. In peace talks with the Ottomans, Russia refused to return the key Ochakov fortress. Pitt wanted to threaten military retaliation. However Russia's ambassador Semyon Vorontsov organised Pitt's enemies and launched a public opinion campaign. Pitt had become alarmed at the opposition to his Russian policy in parliament, Burke and Fox both uttering powerful speeches against the restoration of Ochakov to the Turks. Pitt won the vote so narrowly that he gave up.[45][46] The outbreak of the French Revolution and its attendant wars temporarily united Britain and Russia in an ideological alliance against French republicanism.

The King's condition

In 1788, Pitt faced a major crisis when the King fell victim to a mysterious illness,[lower-alpha 4] a form of mental disorder that incapacitated him. If the sovereign was incapable of fulfilling his constitutional duties, Parliament would need to appoint a regent to rule in his place. All factions agreed that the only viable candidate was the King's eldest son and heir apparent, George, Prince of Wales. The Prince, however, was a supporter of Charles James Fox. Had the Prince come to power, he would almost surely have dismissed Pitt. He did not have such an opportunity, however, as Parliament spent months debating legal technicalities relating to the regency. Fortunately for Pitt, the King recovered in February 1789, just after a Regency Bill had been introduced and passed in the House of Commons.[47]

The general elections of 1790 resulted in a majority for the government, and Pitt continued as prime minister. In 1791, he proceeded to address one of the problems facing the growing British Empire: the future of British Canada. By the Constitutional Act of 1791, the province of Quebec was divided into two separate provinces: the predominantly French Lower Canada and the predominantly English Upper Canada. In August 1792, coincident with the capture of Louis XVI by the French revolutionaries, George III appointed Pitt as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a position whose incumbent was responsible for the coastal defences of the realm.[48] The King had in 1791 offered him a Knighthood of the Garter, but he suggested the honour go to his elder brother, the second Earl of Chatham.[48]

French Revolution

An early favourable response to the French Revolution encouraged many in Great Britain to reopen the issue of parliamentary reform, which had been dormant since Pitt's reform bill was defeated in 1785. The reformers, however, were quickly labelled as radicals and associates of the French revolutionaries. Subsequently, in 1794, Pitt's administration tried three of them for treason but lost. Parliament began to enact repressive legislation in order to silence the reformers. Individuals who published seditious material were punished, and, in 1794, the writ of habeas corpus was suspended. Other repressive measures included the Seditious Meetings Act 1795, which restricted the right of individuals to assemble publicly, and the Combination Acts, which restricted the formation of societies or organisations that favoured political reforms. Problems manning the Royal Navy also led to Pitt to introduce the Quota System in 1795 in addition to the existing system of impressment.[49]

The war with France was extremely expensive, straining Great Britain's finances. Unlike in the latter stages of the Napoleonic Wars, at this point Britain had only a very small standing army, and thus contributed to the war effort mainly through sea power and by supplying funds to other coalition members facing France.

Ideological struggle

Throughout the 1790s, the war against France was presented as an ideological struggle between French republicanism vs. British monarchism with the British government seeking to mobilise public opinion in support of the war.[50] The Pitt government waged a vigorous propaganda campaign contrasting the ordered society of Britain dominated by the aristocracy and the gentry vs. the "anarchy" of the French revolution and always sought to associate British "radicals" with the revolution in France.[51] Though the Pitt government did drastically reduce civil liberties and created a nationwide spy network with ordinary people being encouraged to denounce any "radicals" that might be in their midst, the historian Eric J. Evans argued the picture of Pitt's "reign of terror" as portrayed by the Marxist historian E.P. Thompson is incorrect, stating there is much evidence of a "popular conservative movement" that rallied in defence of King and Country.[52] Evans wrote that there were about 200 prosecutions of "radicals" suspected of sympathy with the French revolution in British courts in the 1790s, which was much less than the prosecutions of suspected Jacobites after the rebellions of 1715 and 1745.[51] However, the spy network maintained by the government was efficient. In Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey, which was written in the 1790s, but not published until 1817, one of the characters remarks that it is not possible for a family to keep secrets in these modern times when spies for the government were lurking everywhere. This comment captures well the tense, paranoid atmosphere of the 1790s, when people were being encouraged to report "radicals" to the authorities.[53]

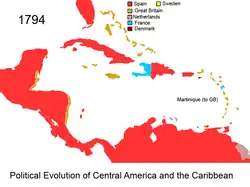

Haiti

In 1793, Pitt decided to take advantage of the Haitian Revolution to seize St. Domingue, the richest French colony in the world, believing this would strike a great blow at France while bringing St. Domingue into the British Empire and ensuring that the slaves in the British West Indies would not be inspired to revolt likewise.[54] Many of those who owned slave plantations in the British West Indies had been greatly alarmed by the revolution, which began in 1791, and they were strongly pressing Pitt to restore slavery in St. Domingue, lest their own slaves be inspired to seek freedom.[55] Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, who was Pitt's Secretary of State for War, instructed Sir Adam Williamson, the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, to sign an agreement with representatives of the French colonists that promised to restore the ancien regime, slavery, and discrimination against mixed-race colonists, a move that drew criticism from abolitionists William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson.[56][57]

The British landed in St. Domingue on 20 September 1793, stating they had come to protect the white population from the blacks, and were able to seize some coastal enclaves.[58] The fact that the British had come to restore slavery in St. Domingue inspired ferocious resistance from the Haitians, who had no desire to be forced into chains again. The heavy death toll caused by yellow fever, the much dreaded "black vomit", made conquering St. Domingue impossible, but an undeterred Pitt launched what he called the "great push" in 1795, sending out an even larger British expedition.[59]

In November 1795, some 218 ships left Portsmouth for St. Domingue.[60] After the failure of the Quiberon expedition earlier in 1795, when the British landed a force of French royalists on the coast of France who were annihilated by the forces of the republic, Pitt had decided it was crucial for Britain to have St. Domingue, no matter what the cost in lives and money, to improve Britain's negotiating hand when it came time to make peace with the French republic.[61] The British historian Michael Duffy argued that since Pitt committed far more manpower and money to the Caribbean expeditions, especially the one to St. Domingue, than he ever did to Europe in the years 1793–1798, it is proper to view the West Indies as Britain's main theatre of war and Europe as more of a sideshow.[62] By 1795, 50% of the British Army was deployed in the West Indies (with the largest contingent in St. Domingue), whereas the rest of the British Army was divided among Britain, Europe, India, and North America.[63]

As the British death toll, largely caused by yellow fever, continued to climb, Pitt was criticised in the House of Commons. Several MPs suggested it might be better to abandon the expedition, but Pitt insisted that Britain had given its word of honour that it would protect the French planters from their former slaves, and the expedition to St. Domingue could not be abandoned.[64] The British attempt to conquer St. Domingue in 1793 ended in disaster; the British pulled out on 31 August 1798 after having spent 4 million pounds (roughly £400.00 million in 2019[65]) and having lost about 100,000 men − dead or crippled for life, mostly from disease – over the preceding five years.[66] The British historian Sir John William Fortescue wrote that Pitt and his cabinet had tried to destroy French power "in these pestilent islands ... only to discover, when it was too late, that they practically destroyed the British army".[59] Fortescue concluded that Pitt's attempt to add St. Domingue to the British empire had killed off most of the British army, cost the British treasury a fortune and weakened British influence in Europe, making British power "fettered, numbered and paralyzed", all for nothing.[67]

Ireland

In May 1798, the long-simmering unrest in Ireland exploded into outright rebellion with the United Irishmen Society launching a revolt to win independence for Ireland.[68] Pitt took an extremely repressive approach to the United Irishmen with the Crown executing about 1,500 United Irishmen after the revolt.[68] The revolt of 1798 destroyed Pitt's faith in the governing competence of the Dublin parliament (dominated by Protestant Ascendancy families). Thinking a less sectarian and more conciliatory approach would have avoided the uprising, Pitt sought an Act of Union that would make Ireland an official part of the United Kingdom and end the "Irish Question".[69] The French expeditions to Ireland in 1796 and 1798 (to support the United Irishmen) were regarded by Pitt as near-misses that might have provided an Irish base for French attacks on Britain, thus making the "Irish Question" a national security matter.[69] As the Dublin parliament did not wish to disband, Pitt made generous use of what would now be called "pork barrel politics" to bribe Irish MPs to vote for the Act of Union.[70]

Throughout the 1790s, the popularity of the Society of United Irishmen grew. Influenced by the American and French revolutions, this movement demanded independence and republicanism for Ireland.[71] The United Irishmen Society was very anti-clerical, being equally opposed to the "superstitions" promoted by both the Church of England and the Roman Catholic church, which caused the latter to support the Crown.[72] Realising that the Catholic church was an ally in the struggle against the French revolution, Pitt had tried fruitlessly to persuade the Dublin parliament to loosen the anti-Catholic laws to "keep things quiet in Ireland".[73] Pitt's efforts to soften the anti-Catholic laws failed in the face of determined resistance from the families of the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, who forced Pitt to recall Earl Fitzwilliam as Chief Secretary for Ireland in 1795, when the latter had indicated he would support a bill for Catholic relief.[74] In much of rural Ireland, law and order had broken down as an economic crisis further impoverished the already poor Irish peasantry, and a sectarian war with many atrocities on both sides had begun in 1793 between Catholic "Defenders" versus Protestant "Peep o' Day Boys".[71] A section of the Peep o'Day Boys who had renamed themselves the Loyal Orange Order in September 1795 were fanatically committed to upholding Protestant supremacy in Ireland at "almost any cost".[71] In December 1796, a French invasion of Ireland led by General Lazare Hoche (scheduled to coordinate with a rising of the United Irishmen) was only thwarted by bad weather.[71] To crush the United Irishmen, Pitt sent General Lake to Ulster in 1797 to call out Protestant Irish militiamen and organised an intelligence network of spies and informers.[71]

Spithead mutiny

In April 1797, the mutiny of the entire Spithead fleet shook the government (sailors demanded a pay increase to match inflation). This mutiny occurred at the same moment that the Franco-Dutch alliance were preparing an invasion of Britain. To regain control of the fleet, Pitt agreed to navy pay increases and had George III pardon the mutineers. By contrast, the more political "floating republic" naval mutiny at the Nore in June 1797 led by Richard Parker was handled more repressively. Pitt refused to negotiate with Parker, whom he wanted to see hanged as a mutineer. In response to the 1797 mutinies, Pitt passed the Incitement to Mutiny Act 1797 making it unlawful to advocate breaking oaths to the Crown. In 1798, he passed the Defence of the Realm act, which further restricted civil liberties.[50]

Failure

Despite Pitt's efforts, the French continued to defeat the First Coalition, which collapsed in 1798. A Second Coalition, consisting of Great Britain, Austria, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, was formed, but it, too, failed to overcome the French. The fall of the Second Coalition with the defeat of the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo (14 June 1800) and at the Battle of Hohenlinden (3 December 1800) left Great Britain facing France alone.

Resignation

Following the Acts of Union 1800, Pitt sought to inaugurate the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland by granting concessions to Roman Catholics, who formed a 75% majority of the population in Ireland, by abolishing various political restrictions under which they suffered. The king was strongly opposed to Catholic emancipation; he argued that to grant additional liberty would violate his coronation oath, in which he had promised to protect the established Church of England. Pitt, unable to change the king's strong views, resigned on 16 February 1801,[75] so as to allow Henry Addington, his political friend, to form a new administration. At about the same time, however, the king suffered a renewed bout of madness, with the consequence that Addington could not receive his formal appointment. Though he had resigned, Pitt temporarily continued to discharge his duties; on 18 February 1801, he brought forward the annual budget. Power was transferred from Pitt to Addington on 14 March, when the king recovered.[76]

Pitt supported the new administration, but with little enthusiasm; he frequently absented himself from Parliament, preferring to remain in his Lord Warden's residence of Walmer Castle – before 1802 usually spending an annual late-summer holiday there, and later often present from the spring until the autumn.

From the castle, he helped organise a local Volunteer Corps in anticipation of a French invasion, acted as colonel of a battalion raised by Trinity House – he was also a Master of Trinity House – and encouraged the construction of Martello towers and the Royal Military Canal in Romney Marsh. He rented land abutting the Castle to farm on which to lay out trees and walks. His niece Lady Hester Stanhope designed and managed the gardens and acted as his hostess.

The Treaty of Amiens in 1802 between France and Britain marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars. Everyone expected it to be only a short truce. By 1803, war had broken out again with France under Napoleon Bonaparte. Although Addington had previously invited him to join the Cabinet, Pitt preferred to join the Opposition, becoming increasingly critical of the government's policies. Addington, unable to face the combined opposition of Pitt and Fox, saw his majority gradually evaporate and resigned in late April 1804.[77]

Second Premiership

Reappointment

Pitt finally returned to the premiership on 10 May 1804. He had originally planned to form a broad coalition government, with both the Tories and Whigs under one government.[78] But Pitt faced the opposition of George III to the inclusion of Fox, due to the King's dislike. Moreover, many of Pitt's former supporters, including the allies of Addington, joined the Opposition. Thus, Pitt's second ministry was considerably weaker than his first.[79]

Nevertheless, Pitt formed a second government which consisted of largely Tory members with some former ministers of the previous ministry. These include Lord Eldon as Lord High Chancellor, former Foreign Secretary Lord Hawkesbury as Home Secretary, Lord Harrowby as Foreign Secretary, former Prime Ministers Duke of Portland and Addington as Lord Privy Seal and Lord President of the Council, with Pitt's prominent allies the Viscount Melville and Lord Castlereagh as First Lord of the Admiralty and Secretary of State for the Colonies respectively..[78]

Resuming war

By the time Pitt became prime minister in 1804, the war in Europe has been escalating for sometime since the peace of Amiens in 1801 and in 1803 War of the Third Coalition begin[78] Pitt's new government resumed the war effort yet again to confront the French and to defeat Napoleon. Pitt initially allied Britain with Austria, Prussia and Russia with its former allies Austria Prussia and Russia against Napoleonic France and its allies.

The British government began placing pressure on the French Emperor, Napoleon I. By imposing sanctions, putting up a blockade across the English Channel and undermining French naval activities, Pitt's efforts proved a success and thanks to his efforts, the United Kingdom joined the Third Coalition, an alliance that included Austria, Russia, and Sweden.[78] In October 1805, the British Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, won a crushing victory in the Battle of Trafalgar, ensuring British naval supremacy for the remainder of the war. At the annual Lord Mayor's Banquet toasting him as "the Saviour of Europe", Pitt responded in a few words that became the most famous speech of his life:

- I return you many thanks for the honour you have done me; but Europe is not to be saved by any single man. England has saved herself by her exertions, and will, as I trust, save Europe by her example.[80]

Nevertheless, the Coalition collapsed, having suffered significant defeats at the Battle of Ulm (October 1805) and the Battle of Austerlitz (December 1805). After hearing the news of Austerlitz Pitt referred to a map of Europe, "Roll up that map; it will not be wanted these ten years."[81]

Finances

Pitt was an expert in finance and served as chancellor of the exchequer.[82] Critical to his success in confronting Napoleon was using Britain's superior economic resources. He was able to mobilize the nation's industrial and financial resources and apply them to defeating France.

With a population of 16 million, the United Kingdom was barely half the size of France, which had a population of 30 million. In terms of soldiers, however, the French numerical advantage was offset by British subsidies that paid for a large proportion of the Austrian and Russian soldiers, peaking at about 450,000 in 1813.[83]

Britain used its economic power to expand the Royal Navy, doubling the number of frigates and increasing the number of the larger ships of the line by 50%, while increasing the roster of sailors from 15,000 to 133,000 in eight years after the war began in 1793. The British national output remained strong, and the well-organized business sector channelled products into what the military needed. France, meanwhile, saw its navy shrink by more than half.[84] The system of smuggling finished products into the continent undermined French efforts to ruin the British economy by cutting off markets.

By 1814, the budget that Pitt in his last years had largely shaped had expanded to £66 million,[lower-alpha 5] including £10 million for the Navy, £40 million for the Army, £10 million for the Allies, and £38 million as interest on the national debt. The national debt soared to £679 million,[lower-alpha 6] more than double the GDP. It was willingly supported by hundreds of thousands of investors and tax payers, despite the higher taxes on land and a new income tax.[85]

The whole cost of the war came to £831 million. The French financial system was inadequate and Napoleon's forces had to rely in part on requisitions from conquered lands.[86][87][88]

Death

The setbacks took a toll on Pitt's health. He had long suffered from poor health, beginning in childhood, and was plagued with gout and "biliousness", which was worsened by a fondness for port that began when he was advised to consume it to deal with his chronic ill-health.[89] On 23 January 1806, Pitt died at Bowling Green House on Putney Heath, probably from peptic ulceration of his stomach or duodenum; he was unmarried and left no children.[90][91]

Pitt's debts amounted to £40,000 when he died, but Parliament agreed to pay them on his behalf.[92][93] A motion was made to honour him with a public funeral and a monument; it passed despite some opposition. Pitt's body was buried in Westminster Abbey on 22 February, having lain in state for two days in the Palace of Westminster.[94]

Pitt was succeeded as Prime Minister by his first cousin William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, who headed the Ministry of All the Talents, a coalition which included Charles James Fox.[95]

Personal life

Pitt became known as a "three-bottle man" in reference to his heavy consumption of port wine. Each of these bottles would be around 350 millilitres (12 US fl oz) in volume.[96]

At one point rumours emerged of an intended marriage to Eleanor Eden, to whom Pitt had grown close. Pitt broke off the potential marriage in 1797, writing to her father, Lord Auckland, "I am compelled to say that I find the obstacles to it decisive and insurmountable".[96]

Of his social relationships, biographer William Hague writes:

Pitt was happiest among his Cambridge companions or family. He had no social ambitions, and it was rare for him to set out to make a friend. The talented collaborators of his first 18 months in office—Beresford, Wyvil and Twining—passed in and out of his mind along with their areas of expertise. Pitt's lack of interest in enlarging his social circle meant that it did not grow to encompass any women outside his own family, a fact that produced a good deal of rumour. From late 1784, a series of satirical verses appeared in The Morning Herald drawing attention to Pitt's lack of knowledge of women: "Tis true, indeed, we oft abuse him,/Because he bends to no man;/But slander's self dares not accuse him/Of stiffness to a woman." Others made snide references to Pitt's friendship with Tom Steele, Secretary to the Treasury. At the height of the constitutional crisis in 1784, Sheridan had compared Pitt to James I's favourite, the Duke of Buckingham, a clear reference to homosexuality. Socially, Pitt preferred the company of young men, and would continue to do so into his thirties and forties. It may be that Pitt had homosexual leanings but suppressed any urge to act on them for the sake of his ambitions. He could be charming to women, but it seems certain that he rejected intimacy whenever it was proffered—and would do so publicly at a later date. In practical terms it appears that Pitt was essentially asexual throughout his life.[96]

Legacy

William Pitt the Younger was a prime minister who consolidated the powers of his office. Though he was sometimes opposed by members of his Cabinet, he helped define the role of the Prime Minister as the supervisor and co-ordinator of the various government departments. After his death the conservatives embraced him as a great patriotic hero.[97]

One of Pitt's accomplishments was a rehabilitation of the nation's finances after the American War of Independence.[98] Pitt made changes to the tax system in order to improve its capture of revenue, which helped manage the mounting national debt.[98]

Some of Pitt's domestic plans were not successful; he failed to secure parliamentary reform, emancipation, or the abolition of the slave trade although this last took place with the Slave Trade Act 1807, the year after his death. The 1792 Slave Trade Bill passed the House of Commons mangled and mutilated by the modifications and amendments of Pitt, it lay for years, in the House of Lords.[99][100] Biographer William Hague considers the unfinished abolition of the slave trade to be Pitt's greatest failure.[101] He notes that by the end of Pitt's career, conditions were in place that would have allowed a skillful attempt to pass an abolition bill to succeed, partly because of the long campaigning Pitt had encouraged with his friend William Wilberforce. Hague goes on to note that the failure was likely due to Pitt being a "spent force" by the time favourable conditions had arisen. In Hague's opinion, Pitt's long premiership, "tested the natural limits of how long it is possible to be at the top. From 1783 to 1792, he faced each fresh challenge with brilliance; from 1793 he showed determination but sometimes faltered; and from 1804 he was worn down by ... the combination of a narrow majority and war".[102]

Historian Marie Peters has compared his strengths and weaknesses with his father:

- Having some of his father's volatility and much of the self-confidence bordering on arrogance, the younger Pitt inherited superb and carefully nurtured oratorical gifts. These gave him, like his father, unsurpassed command of the Commons and power to embody the national will in wartime. There were, however, significant differences. The younger Pitt's eloquence, unlike his father's, included the force of sustained reasoned exposition. This was perhaps in part expression of his thoroughly professional approach to politics, so unlike his father's, but possibly deriving something from Shelburne. The younger Pitt was continuously engaged in depth with major issues of his day. He regularly and energetically sought the best information. He was genuinely progressive, as his father was not, on parliamentary reform, Catholic emancipation, commercial policy, and administrative reform. His constructive capacity in his chief responsibility, financial policy and administration, far surpassed his father's record, if it was less impressive and perhaps more equally matched in foreign and imperial policy and strategy. With good reason, his long career in high office was the mirror image of his father's short tenure. In contrast, only briefly was Chatham able to rise to the challenge of his age. By his last decade time had passed him by.[103]

Cultural references

Film and television

William Pitt is depicted in several films and television programs.

- Robert Donat portrays Pitt in the 1942 biopic The Young Mr. Pitt, which chronicles the historical events of Pitt's life.

- Pitt's attempts during his tenure as Prime Minister to cope with the dementia of King George III are portrayed by Julian Wadham in the 1994 film The Madness of King George.

- The 2006 film Amazing Grace, with Benedict Cumberbatch in the role of Pitt, depicts his close friendship with William Wilberforce, the leading abolitionist in Parliament.[104]

- Pitt is caricatured as a boy prime minister in the third series of the television comedy Blackadder, in which Simon Osborne plays a fictionalised Pitt as a petulant teenager who has just come to power "right in the middle of [his] exams" in the episode Dish and Dishonesty. A fictionalised younger brother, "Pitt the Even Younger", appeared as a candidate standing in the Dunny-on-the-Wold by-election.

- In the series of prime ministerial biographies Number 10, produced by Yorkshire Television, Pitt was portrayed by Jeremy Brett.

- In the first episode of the 2016 ITV TV series Victoria, written by Daisy Goodwin, Lord Melbourne cites Pitt the Younger becoming Prime Minister at 24 as a reason why youth should not disqualify the 18-year-old Queen Victoria from ruling Britain.

Places named after him

- The University Pitt Club, a club for students at the University of Cambridge, was founded in 1835 "to do honour to the name and memory of Mr William Pitt".[105][106]

- Pittwater in Australia was named in 1788 by British explorer Arthur Phillip.[107]

- Pitt Street is the main financial precinct street in the Central business district of Sydney.

- Pitt Town near Windsor outside of Sydney, together with another township called Wilberforce.

- Mount Pitt, second highest mountain on Norfolk Island

- Pitt Water, a body of water in South East Tasmania

- Pitt's Head in Snowdonia National Park in Wales was named after the rock formation's resemblance to the Prime Minister.

- While Chatham County, North Carolina was named after his father, Pittsboro, North Carolina was named after Pitt the Younger.

- In Penang, Malaysia, Pitt Street and Pitt Lane were named for him, as British Prime Minister when George Town was founded in 1786.

- In Hong Kong, a street on Kowloon side, Pitt Street, is named after him.

- Pittsburgh, Ontario

- Pitt Street in Glasgow is named after William Pitt the Younger.

- Pitt Street in Windsor, Ontario

- Pitt Street in Kingston, Ontario

- Pitt Street in Cornwall, Ontario

- Rue Pitt, Montreal Quebec

- Chemin Pitt, Montreal Quebec

- Pitt Street, Sydney Mines, Nova Scotia

- Pitt Street, Saint John New Brunswick

- Pitt House, High Wycombe Buckinghamshire

- Pitt's Cottage Westerham, Kent, former home of Pitt the Younger and more recently a local curry house (now closed)

- The Pitt River, in British Columbia, Canada

- William Pitt Avenue, Deal, Kent

- Pitt Street in Southport, England

- Pitt Street in Auckland, New Zealand

Note, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was named for his father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham.[108]

Footnotes

- about £33 billion today

- about £19 billion today

- about £269 million today

- The consensus view among historians is that the King was suffering from the blood disorder porphyria, which was unknown at this time. If protracted and untreated, it has serious mentally debilitating effects.

- about £4 billion today

- about £46 billion today

References

- Briggs 1959, pp. 148–149.

- Charles Petrie, "The Bicentenary of the Younger Pitt", Quarterly Review, 1959, Vol. 297 Issue 621, pp 254–265

- Strangio, Hart & Walter 2013, p. 225.

- Wise, Hansen & Egan 2005, p. 298.

- Hague 2005, p. 14.

- Hague 2005, p. 19.

- Ehrman 1969, p. 4, Vol. 1.

- "Pitt, the Hon. William (PT773W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806) HistoryHome.co.uk

- "Spartacus Educational – William Pitt". Spartacus-Educational.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- "History – William Wilberforce (1759–1833)". BBC. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Hague 2005, p. 30.

- Halcombe 1859, p. 110.

- Hague 2005, p. 46.

- "William Pitt, the Younger: Historical importance". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "William Pitt 'The Younger' 1783–1801 and 1804-6 Tory". 10 Downing Street – PMs in history. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- Hague 2005, p. 89.

- Hague 2005, pp. 62–65.

- Hague 2005, p. 71.

- Hague 2005, p. 99.

- Hague 2005, p. 124.

- Black 2006.

- Canny 1998, p. 92.

- Hague 2005, p. 140.

- Hague 2005, p. 146.

- Paul Kelly, "British Politics, 1783-4: The Emergence and Triumph of the Younger Pitt's Administration," Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research Vol. 54 Issue 129, pp 62–78

- Short 1785, p. 61.

- Kilburn, Matthew (24 May 2008). "Mince-pie administration (act. 1783–1784)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95200.

The name "mince-pie administration" was created by Frances Anne Crewe, Lady Crewe, a Whig political hostess.

(Subscription or UK public library membership required.) citing (Ehrman 1969, p. 133) - Hague 2005, p. 152.

- Hague 2005, p. 166.

- Hague 2005, p. 173.

- Hague 2005, p. 170.

- Hague 2005, p. 191.

- Hague 2005, p. 193.

- Hague 2005, p. 182.

- "Why were convicts transported to Australia". Sydney Living Museums. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- George Burnett Barton (1889). "History of New South Wales From the Records, Volume I - Governor Phillip - Chapter 1.4". Project Gutenberg of Australia. Charles Potter, Government Printer.

- Turner 2003, p. 94.

- Foster, R. E. (March 2009). "Forever Young: Myth, Reality and William Pitt". History Review. No. 63. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013.

- Hoh-Cheung; Mui, Lorna H. (1961). "William Pitt and the Enforcement of the Commutation Act, 1784-1788". The English Historical Review. 76 (300): 447–465. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXVI.CCC.447. JSTOR 558296.

- Thompson, S. J.; "The first income tax, political arithmetic, and the measurement of economic growth"; Economic History Review, Vol. 66, No. 3 (2013), pp. 873-894; JSTOR 42922026

- Black 1994, p. .

- Turner 2003, pp. 149–155.

- Holland Rose, John, William Pitt and National Revival (1911) pp. 589-607.

- Black 1994, p. 290.

- Ehrman 1969, p. xx, Vol. 2.

- Gronbeck, Bruce E. (Fall 1970). "Government's Stance in Crisis: A Case Study of Pitt the Younger". Western Speech. 34 =issue=4: 250–261.

- Hague 2005, p. 309.

- Ennis 2002, p. 34.

- Evans 2002, p. 57.

- Evans 2002, p. 59.

- Evans 2002, p. 58.

- Irvine 2005, p. 93.

- Perry 2005, pp. 63–64.

- Duffy 1987, p. 28.

- James 1938, p. 109.

- Geggus 1982, p. .

- Perry 2005, p. 64.

- Perry 2005, p. 69.

- Duffy 1987, p. 197.

- Duffy 1987, p. 162.

- Duffy 1987, pp. 370–372.

- Evans 2002, p. 50.

- Perry 2005, p. 73.

- United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Perry 2005, pp. 75–76.

- Perry 2005, p. 76.

- Evans 2002, pp. 67–68.

- Evans 2002, p. 68.

- Evans 2002, pp. 68–69.

- Evans 2002, p. 67.

- Evans 2002, p. 65.

- Evans 2002, p. 66.

- Evans 2002, pp. 66–67.

- Hague 2005, p. 479.

- Hague 2005, p. 484.

- Hague 2005, p. 526.

- "William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806)".

- Hague 2005, pp. 529–533.

- Hague 2005, p. 565.

- Stanhope 1862, p. 369.

- O'Brien, Patrick; "Political Biography and Pitt the Younger as Chancellor of the Exchequer"; History (1998) Vol. 83, No. 270, pp. 225–233.

- Kennedy 1987, pp. 128–129.

- Briggs 1959, p. 143.

- Cooper, Richard (1982). "William Pitt, Taxation, and the Needs of War". Journal of British Studies. 22 (1): 94–103. doi:10.1086/385799. JSTOR 175658.

- Halévy 1924, pp. 205–228.

- Knight 2014, p. .

- Watson 1960, pp. 374–277, 406–407, 463–471.

- Marjie Bloy (4 January 2006). "William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806)". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Hague 2005, p. 578.

- "Bowling Green House, Putney Heath". The Private Life of William Pitt (1759-1806). 13 November 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "PITT, Hon. William (1759–1806), of Holwood and Walmer Castle, Kent". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- "William Pitt the Younger". Regency History. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Fitzwilliam Museum (1978). Cambridge Portraits from Lely to Hockney. Exhibition catalogs, No. 86. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521223119.

- Hague 2005, p. 581.

- Hague, William (31 August 2004). "He was something between God and man". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- Sack, J. J. (1987). "The Memory of Burke and the Memory of Pitt: English Conservatism Confronts Its Past, 1806-1829". The Historical Journal. 30 (3): 623–640. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00020914. JSTOR 2639162. S2CID 154447696.

- Cooper, Richard (1982). "William Pitt, Taxation, and the Needs of War". Journal of British Studies. 22 (1): 94–103. doi:10.1086/385799. ISSN 0021-9371. JSTOR 175658.

- Parliament, Great Britain (1817). Cobbett's Parliamentary History of England, from the Earliest Period to the Year 1803. Vol. XXIX. p. 1293.

- Journal of the House of Lords. Vol. XXXIX. H.M. Stationery Office. 1790. pp. 391–738.

- Hague 2005, p. 589.

- Hague 2005, p. 590.

- Peters, Marie (23 September 2004). "Pitt, William, first earl of Chatham [Pitt the elder] (1708–1778)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22337. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Amazing Grace (movie)". Amazinggracemovie.com. 23 February 2007. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Fletcher 2011, p. 1.

- Hogan, Aoife (10 November 2017). "Pitt Club vote to allow female members". Varsity.

- "Pittwater's past". Pittwater.nsw.gov.au. Pittwater Library. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- "The Pittsburgh 'H'". Visit Pittsburgh. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

Sources

- Ehrman, John (1969–1996). The Younger Pitt. Constable & Co. (3 volumes)

- Ehrman, John (1969). The Younger Pitt, Vol. 1: The Years of Acclaim. Constable. ISBN 978-0-09455720-8.

- Ehrman, John (1983). The Younger Pitt, Vol. 2: The Reluctant Transition. Constable. ISBN 978-0-09464930-9.

- Ehrman, John (1996). The Younger Pitt, Vol. 3: The Consuming Struggle. Constable. ISBN 978-0-09475540-6.

- Black, Jeremy (1994). British Foreign Policy in an Age of Revolutions, 1783-1793. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521466844.

- Black, Jeremy (2006). "Pitt and the king". George III: America's Last King. pp. 264–287.

- Briggs, Asa (1959). The Making of Modern England 1783–1867: The Age of Improvement.

- Canny, Nicholas (1998). The Origins of Empire, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924676-2. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Duffy, Michael (1987). Soldiers, Sugar, and Seapower: The British Expeditions to the West Indies and the War Against Revolutionary France. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ennis, Daniel (2002). Enter the press-gang: naval impressment in eighteenth-century British literature. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-755-2.

- Evans, Eric (2002). William Pitt the Younger. London: Routledge.

- Fletcher, Walter Morley (2011) [1935]. The University Pitt Club: 1835–1935 (First Paperback ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60006-5.

- Geggus, David (1982). Slavery, War and Revolution: The British Occupation of Saint Domingue, 1793–1798. New York: Clarendon Press.

- Hague, William (2005). William Pitt the Younger. HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-00-714720-5.

- Halévy, Élie (1924). A History of the English People in 1815, Book 2.

- Halcombe, J. J (1859). The Speaker at Home. London: Bell and Daldy.

- Irvine, Robert (2005). Jane Austen. London: Routledge.

- James, C.L.R. (1938). Black Jacobins. London: Penguin.

- Kennedy, Paul (1987). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780394546742.

- Knight, Roger (2014). Britain Against Napoleon: The Organisation of Victory, 1793–1815. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141038940.

- Perry, James (2005). Arrogant Armies: Great Military Disasters and the Generals Behind Them. Edison: Castle Books.

- Short, D., ed. (1785). Criticisms on the Rolliad: Part the First (2nd ed.). London: James Ridgway. OCLC 5203303.

- Stanhope, Philip Henry (1862). Life of the Right Honourable William Pitt, Vol. IV. John Murray.

- Strangio, Paul; Hart, Paul 't; Walter, James (2013). Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199666423.

- Turner, Michael (2003). Pitt the younger: a life. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85285-377-8.

- Watson, J. Steven (1960). The Reign of George III 1760–1815. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198217138.

- Wise, Leonard F.; Hansen, Mark Hillary; Egan, E. W. (2005). Kings, Rulers, and Statesmen. Sterling. ISBN 9781402725920.

Further reading

Biographical

- Carlyle, Thomas (1903). "William Pitt, the Younger". Critical and Miscellaneous Essays: Volume V. The Works of Thomas Carlyle in Thirty Volumes. Vol. XXX. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons (published 1904). pp. 152–167.

- Duffy, Michael (2000). The Younger Pitt (Profiles In Power). Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-05279-6.

- Ehrman, J. P. W., and Anthony Smith. "Pitt, William (1759–1806)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004); online 2009; accessed 12 September 2011

- Evans, Eric J. William Pitt the Younger (1999) 110 pages; online Archived 30 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Furber, Holden. Henry Dundas: First Viscount Melville, 1741–1811, Political Manager of Scotland, Statesman, Administrator of British India (Oxford UP, 1931). online

- Jarrett, Derek (1974). Pitt the Younger. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ASIN B002AMOXYK., a short scholarly biography

- Jupp, Peter. "Grenville, William Wyndham, Baron Grenville (1759–1834)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2009) doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11501

- Jupp, P. (1985), Lord Grenville, Oxford University Press

- Leonard, Dick. "William Pitt, the Younger—Reformer Turned Reactionary?." in Leonard, ed. Nineteenth-Century British Premiers (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2008) pp. 5–27.

- Mori, Jennifer. William Pitt & the French Revolution, 1785–1795 (1997) 305pp

- Mori, Jennifer. "William Pitt the Younger" in R. Eccleshall and G. Walker, eds., Biographical Dictionary of British Prime Ministers (Routledge, 1998), pp. 85–94

- Reilly, Robin (1978). Pitt the Younger 1759–1806. Cassell Publishers. ASIN B001OOYKNE.

- Rose, J. Holland. William Pitt and National Revival (1911); William Pitt and the Great War (1912), solid, detailed study superseded by Ehrman; vol 1; vol 2 free;

- Stanhope, Philip Henry [5th Earl Stanhope] (1861–1862). Life of the Right Honourable William Pitt. John Murray.. (4 volumes); includes many extracts from Pitt's correspondence vol 1 online; vol 2 online

Scholarly studies

- Blanning, T. C. W. The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787–1802 (1996)

- Bryant, Arthur. Years of Endurance 1793–1802 (1942); and Years of Victory, 1802–1812 (1944), well-written surveys of the British story

- Cooper, William. "William Pitt, Taxation, and the Needs of War," Journal of British Studies Vol. 22, No. 1 (Autumn, 1982), pp. 94–103 JSTOR 175658

- Derry, J. Politics in the Age of Fox, Pitt and Liverpool: Continuity and Transformation (1990)

- Gaunt, Richard A. From Pitt to Peel: Conservative Politics in the Age of Reform (2014)

- Kelly, Paul. "British Politics, 1783-4: The Emergence and Triumph of the Younger Pitt's Administration," Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research Vol. 54, No. 123 (1981) pp. 62–78.

- Ledger-Lomas, Michael. "The Character of Pitt the Younger and Party Politics, 1830–1860." The Historical Journal Vol. 47, No. 3 (2004), pp. 641–661 JSTOR 4091759

- Mori, Jennifer. "The political theory of William Pitt the Younger," History, April 1998, Vol. 83 Issue 270, pp. 234–248

- Richards, Gerda C. "The Creations of Peers Recommended by the Younger Pitt," American Historical Review Vol. 34, No. 1 (October 1928), pp. 47–54 JSTOR 1836479

- Sack, James J. From Jacobite to Conservative: Reaction and Orthodoxy in Britain c.1760–1832 (Cambridge University Press, 1993), does not see Pitt as a Tory

- Sack, James J. The Grenvillites, 1801–29: Party Politics and Factionalism in the Age of Pitt and Liverpool (U. of Illinois Press, 1979)

- Simms, Brendan. "Britain and Napoleon," The Historical Journal Vol. 41, No. 3 (1998) pp. 885–894 JSTOR 2639908

- Wilkinson, D. "The Pitt-Portland Coalition of 1794 and the Origins of the 'Tory' party" History Vol. 83 (1998), pp. 249–264

Historiography and memory

- Foster, R. E. "Forever Young: Myth, Reality and William Pitt," History Review (March 2009) No. 63

- Ledger-Lomas, Michael. "The Character of Pitt the Younger and Party Politics, 1830–1860" The Historical Journal, Vol. 47, No. 3 (2004) pp. 641–661

- Loades, David Michael, ed. Reader's guide to British history (2003) 2: 1044–45

- Moncure, James A. ed. Research Guide to European Historical Biography: 1450–Present (4 vol 1992); 4:1640–46

- Petrie, Charles, "The Bicentenary of the Younger Pitt," Quarterly Review (1959), Vol. 297 Issue 621, pp 254–265

- Sack, J. J. "The Memory of Burke and the Memory of Pitt: English Conservatism Confronts its Past, 1806–1829," The Historical Journal Vol. 30, No. 3 (1987) pp. 623–640 JSTOR 2639162, shows that after his death the conservatives embraced him as a great patriotic hero.

- Turner, Simon. ‘I will not alter an Iota for any Mans Opinion upon Earth’: "James Gillray's Portraits of William Pitt the Younger" in Kim Sloan et al. eds., Burning Bright: Essays in Honour of David Bindman (2015) pp. 197–206.

Primary sources

- Pitt, William. The Speeches of the Right Honourable William Pitt, in the House of Commons (1817) online edition

- Temperley, Harold and L.M. Penson, eds. Foundations of British Foreign Policy: From Pitt (1792) to Salisbury (1902) (1938), primary sources online

External links

- 1791 Caricature of William Pitt by James Gillray

- Pitt the Younger on the 10 Downing Street website

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- After Words interview with William Hague on his book William Pitt the Younger, February 27, 2005

- Hutchinson, John (1892). . Men of Kent and Kentishmen (Subscription ed.). Canterbury: Cross & Jackman. pp. 108–110.

- Biographies of William Pitt at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

_(14797903353).jpg.webp)

_(2022).svg.png.webp)