Preslav Literary School

The Preslav Literary School (Bulgarian: Преславска книжовна школа), also known as the '''Pliska Literary School''' or '''Pliska-Preslav Literary school''' was the first literary school in the medieval First Bulgarian Empire. It was established by Boris I in 886 in Bulgaria's capital, Pliska. In 893, Simeon I moved the seat of the school from the First Bulgarian capital Pliska to the new capital, Veliki Preslav. Preslav was captured and burnt by the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimisces in 972 in the aftermath of Sviatoslav's invasion of Bulgaria.

History

The Preslav Literary School was the most important literary and cultural centre of the Bulgarian Empire and of all Slavs. A number of prominent Bulgarian writers and scholars worked at the school, including Naum of Preslav until 893; Constantine of Preslav; Joan Ekzarh (also transcr. John the Exarch); and Chernorizets Hrabar, among others. The school was also a centre of translation, mostly of Byzantine authors. Finally, it was a centre of poetry, of painting, and of painted ceramics.

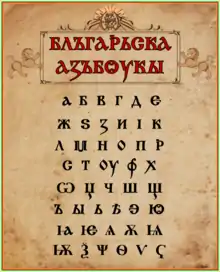

The school developed the Cyrillic script:

Unlike the Churchmen in Ohrid, Preslav scholars were much more dependent upon Greek models and quickly abandoned the Glagolitic scripts in favor of an adaptation of the Greek uncial to the needs of Slavic, which is now known as the Cyrillic alphabet.[1]

The earliest datable Cyrillic inscriptions have been found in the area of Preslav. They have been found in the medieval city itself, and at nearby Patleina Monastery, both in present-day Shumen Province, in the Ravna Monastery and in the Varna Monastery.

In Ravna, an unusually large number of inscriptions in the form of 330 instances of graffiti were found, written in Old Slavonic and in other languages. Many were written by lay people, and some are obscene. Some were written in both Cyrillic and other alphabets,[2] prompting Umberto Eco to label Ravna "a 10th-century language laboratory". Another impressive body of 10th-century Cyrillic inscriptions has been found in the form of a number of leaden pendants, the bulk of which have also been found in an area in northeastern Bulgaria between Preslav and Varna but also extending north into present-day southeastern Romania.[3]

The Preslav School scriptoria where works were created were scattered over much of present-day northeastern Bulgaria, including churches and monasteries at Preslav, where the remains of 25 churches have been found. Other locations include Pliska, Patleina, Khan Krum, and Chernoglavtsi which are all in present-day Shumen Province; Ravna, in Varna Province; and finally Murfatlar in Dobruja, now in Romania.[4][5]

Literature

In the book center of the school, literature in the Old Bulgarian language was created, effectually bringing to an end the so-called trilingual heresy. In the monasteries were also made translations of the Bible, the Slavonic Josephus, the Antiquities of the Jews, and the Alexander Romance.

See also

References

- Curta, Florin (September 18, 2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250 (Cambridge Medieval Textbooks). Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–222.

- Silent Communication: Graffiti from the Monastery of Ravna, Bulgaria. Studien Dokumentationen. Mitteilungen der ANISA. Verein für die Erforschung und Erhaltung der Altertümer, im speziellen der Felsbilder in den österreichischen Alpen (Verein ANISA: Grömbing, 1996) 17. Jahrgang/Heft 1, 57–78.

- Curta, Florin, Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250 (Cambridge Medieval Textbooks), Cambridge University Press (September 18, 2006), p. 222.

- "The scriptorium of the Ravna monastery: once again on the decoration of the Old Bulgarian manuscripts 9th–10th c." In: Medieval Christian Europe: East and West. Traditions, Values, Communications. Eds. Gjuzelev, V. and Miltenova, A. (Sofia: Gutenberg Publishing House, 2002), 719–726 (with K. Popkonstantinov)

- Popkonstantinov, Kazimir, Die Inschriften des Felsklosters Murfatlar. In: Die slawischen Sprachen 10, 1986, S. 77–106.