Polygamy

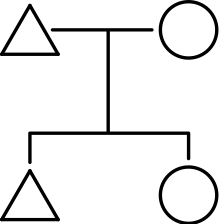

Polygamy (from Late Greek πολυγαμία (polugamía) "state of marriage to many spouses")[1][2][3][4] is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married to more than one husband at a time, it is called polyandry. In sociobiology and zoology, researchers use polygamy in a broad sense to mean any form of multiple mating.

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of kinship |

|---|

|

|

Social anthropology Cultural anthropology |

In contrast to polygamy, monogamy is marriage consisting of only two parties. Like "monogamy", the term "polygamy" is often used in a de facto sense, applied regardless of whether a state recognizes the relationship.[note 1] In many countries, the law only recognises monogamous marriages (a person can only have one spouse, and bigamy is illegal), but adultery is not illegal, leading to a situation of de facto polygamy being allowed without legal recognition for non-official "spouses".

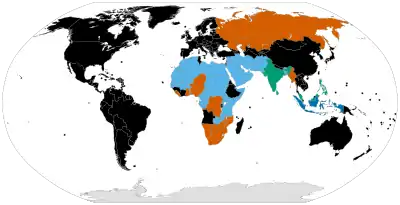

Worldwide, different societies variously encourage, accept or outlaw polygamy. In societies which allow or tolerate polygamy, polygyny is the accepted form in the vast majority of cases. According to the Ethnographic Atlas Codebook, of 1,231 societies noted between from 1960 to 1980, 588 had frequent polygyny, 453 had occasional polygyny, 186 were monogamous, and 4 had polyandry[5] – although more recent research found some form of polyandry in 53 communities, which is more common than previously thought.[6] In cultures which practice polygamy, its prevalence among that population often correlates with social class and socioeconomic status.[7] Polygamy (taking the form of polygyny) is most common in a region known as the "polygamy belt" in West Africa and Central Africa, with the countries estimated to have the highest polygamy prevalence in the world being Burkina Faso, Mali, Gambia, Niger and Nigeria.[8]

Biological and social distinctions

The term "polygamy" may be referring to one of various relational types, depending upon context. Four overlapping definitions can be adapted from the work of Ulrich Reichard and others:[9]

- Marital polygamy occurs when an individual is married to more than one person. The other spouses may or may not be married to one another.

- Social polygamy occurs when an individual has multiple partners that they live with, have sex with, and cooperate with in acquiring basic resources (such as shelter, food and money).

- Sexual polygamy refers to individuals who have more than one sexual partner or who have sex partners outside of a primary relationship.

- Genetic polygamy refers to sexual relationships that result in children who have genetic evidence of different paternity.

Biologists, biological anthropologists, and behavioral ecologists often use polygamy in the sense of a lack of sexual or genetic (reproductive) exclusivity.[10] When cultural or social anthropologists and other social scientists use the term polygamy, the meaning is social or marital polygamy.[10][9]

In contrast, marital monogamy may be distinguished between:

- classical monogamy, "a single relationship between people who marry as virgins, remain sexually exclusive their entire lives, and become celibate upon the death of the partner"[11]

- serial monogamy, marriage with only one other person at a time, in contrast to bigamy or polygamy[12] Some definitions of serial monogamy consider it to be polygamy, as it can result in evidence of genetic polygamy. It can also be considered polygamy for anthropological reasons. See Serial monogamy.

Outside of the legal sphere, defining polygamy can be difficult because of differences in cultural assumptions regarding monogamy. Some societies believe that monogamy requires limiting sexual activity to a single partner for life.[11][13] Others accept or endorse pre-marital sex prior to marriage.[14] Some societies consider sex outside of marriage[15] or "spouse swapping"[16] to be socially acceptable. Some consider a relationship monogamous even if partners separate and move to a new monogamous relationship through death, divorce, or simple dissolution of the relationship, regardless of the length of the relationship (serial monogamy).[17] Anthropologists characterize human beings as “mildly polygynous” or “monogamous with polygynous tendencies.”[18][19][20][21] The average pre-historic man with modern descendents appears to have had children with between 1.5 women (70,000 years ago) to 3.3 women (45,000 years ago), except in East Asia.[22][23] While the forms of non-monogamy in prehistorical times is unknown, these rates could be consistent with a society that practices serial monogamy. Anthropological observations indicate that even when polygyny is accepted in the community, the majority of relationships in the society are monogamous in practice – while couples remain in the relationship, which may not be lifelong.[17] Thus, in many historical communities, serial monogamy may have been the accepted practice rather than a lifelong monogamous bond.[17] The genetic record indicates that monogamy increased within the last 5,000-10,000 years,[24] a period associated with the development of human agriculture, non-communal land ownership, and inheritance.[25]

Forms

Polygamy exists in three specific forms:

- Polygyny, where a man has multiple simultaneous wives

- Polyandry, where a woman has multiple simultaneous husbands

- Group marriage, where the family unit consists of multiple husbands and multiple wives of legal age

Polygyny

.svg.png.webp)

Incidence

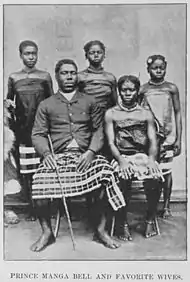

Polygyny, the practice wherein a man has more than one wife at the same time, is by far the most common form of polygamy. Many Muslim-majority countries and some countries with sizable Muslim minorities accept polygyny to varying extents both legally and culturally. In several countries, such as India, the law only recognizes polygamous marriages for the Muslim population. Islamic law or sharia is a religious law forming part of the Islamic tradition which allows polygyny.[26][27] It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam, particularly the Quran and the hadith. In Arabic, the term sharīʿah refers to God's (Arabic: الله Allāh) immutable divine law and is contrasted with fiqh, which refers to its human scholarly interpretations.[28][29][30]

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than on any other continent,[31][32] especially in West Africa, and some scholars see the slave trade's impact on the male-to-female sex ratio as a key factor in the emergence and fortification of polygynous practices in regions of Africa.[33] In the region of sub-Saharan Africa, polygyny is common and deeply rooted in the culture, with 11% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa living in such marriages (25% of the Muslim population and 3% of the Christian population, as of 2019).[34] According to Pew, polygamy is widespread in a cluster of countries in West and Central Africa, including Burkina Faso, (36%), Mali (34%) and Nigeria (28%).[34]

Anthropologist Jack Goody's comparative study of marriage around the world utilizing the Ethnographic Atlas demonstrated a historical correlation between the practice of extensive shifting horticulture and polygamy in the majority of sub-Saharan African societies.[25] Drawing on the work of Ester Boserup, Goody notes that the sexual division of labour varies between the male-dominated intensive plough-agriculture common in Eurasia and the extensive shifting horticulture found in sub-Saharan Africa. In some of the sparsely-populated regions where shifting cultivation takes place in Africa, women do much of the work. This favours polygamous marriages in which men seek to monopolize the production of women "who are valued both as workers and as child bearers". Goody however, observes that the correlation is imperfect and varied, and also discusses more traditionally male-dominated though relatively extensive farming systems such as those traditionally common in much of West Africa, especially in the West African savanna, where more agricultural work is done by men, and where polygyny is desired by men more for the generation of male offspring whose labor is valued.[35]

Anthropologists Douglas R. White and Michael L. Burton discuss and support Jack Goody's observation regarding African male farming systems in "Causes of Polygyny: Ecology, Economy, Kinship, and Warfare"[36]: 884 where these authors note:

Goody (1973) argues against the female contributions hypothesis. He notes Dorjahn's (1959) comparison of East and West Africa, showing higher female agricultural contributions in East Africa and higher polygyny rates in West Africa, especially the West African savanna, where one finds especially high male agricultural contributions. Goody says, "The reasons behind polygyny are sexual and reproductive rather than economic and productive" (1973:189), arguing that men marry polygynously to maximize their fertility and to obtain large households containing many young dependent males.[36]: 873

.jpg.webp)

An analysis by James Fenske (2012) found that child mortality and ecologically related economic shocks had a significant association with rates of polygamy in sub-Saharan Africa, rather than female agricultural contributions (which are typically relatively small in the West African savanna and sahel, where polygyny rates are higher), finding that polygyny rates decrease significantly with child mortality rates.[37]

Types of polygyny

Polygynous marriages fall into two types: sororal polygyny, in which the co-wives are sisters, and non-sororal, where the co-wives are not related. Polygyny offers husbands the benefit of allowing them to have more children, may provide them with a larger number of productive workers (where workers are family), and allows them to establish politically useful ties with a greater number of kin groups.[38] Senior wives can benefit as well when the addition of junior wives to the family lightens their workload. Wives', especially senior wives', status in a community can increase through the addition of other wives, who add to the family's prosperity or symbolize conspicuous consumption (much as a large house, domestic help, or expensive vacations operate in a western country). For such reasons, senior wives sometimes work hard or contribute from their own resources to enable their husbands to accumulate the bride price for an extra wife.[39]

Polygyny may also result from the practice of levirate marriage. In such cases, the deceased man's heir may inherit his assets and wife; or, more usually, his brothers may marry the widow. This provides support for the widow and her children (usually also members of the brothers' kin group) and maintains the tie between the husbands' and wives' kin groups. The sororate resembles the levirate, in that a widower must marry the sister of his dead wife. The family of the late wife, in other words, must provide a replacement for her, thus maintaining the marriage alliance. Both levirate and sororate may result in a man having multiple wives.[38]

.jpg.webp)

In monogamous societies, wealthy and powerful men may establish enduring relationships with, and established separate household for, multiple female partners, aside from their legitimate wives; a practice accepted in Imperial China up until the Qing Dynasty of 1636–1912. This constitutes a form of de facto polygyny referred to as concubinage.[40]

Household organization

Marriage is the moment at which a new household is formed, but different arrangements may occur depending upon the type of marriage and some polygamous marriages do not result in the formation of a single household. In many polygynous marriages the husband's wives may live in separate households.[41] They can thus be described as a "series of linked nuclear families with a 'father' in common".[42]

Polyandry

.svg.png.webp)

Incidence

Polyandry, the practice of a woman having more than one husband at one time, is much less prevalent than polygyny. It is specifically provided in the legal codes of some countries, such as Gabon.[43]

Polyandry is believed to be more common in societies with scarce environmental resources, as it is believed to limit human population growth and enhance child survival.[44] It is a rare form of marriage that exists not only among poor families, but also the elite.[45] For example, in the Himalayan Mountains polyandry is related to the scarcity of land; the marriage of all brothers in a family to the same wife allows family land to remain intact and undivided.[6] If every brother married separately and had children, family land would be split into unsustainable small plots. In Europe, this outcome was avoided through the social practice of impartible inheritance, under which most siblings would be disinherited.[46]

Types

Fraternal polyandry was traditionally practiced among nomadic Tibetans in Nepal, parts of China and part of northern India, in which two or more brothers would marry the same woman. It is most common in societies marked by high male mortality. It is associated with partible paternity, the cultural belief that a child can have more than one father.[6]

Non-fraternal polyandry occurs when the wives' husbands are unrelated, as among the Nayar tribe of India, where girls undergo a ritual marriage before puberty,[47] and the first husband is acknowledged as the father of all her children. However, the woman may never cohabit with that man, taking multiple lovers instead; these men must acknowledge the paternity of their children (and hence demonstrate that no caste prohibitions have been breached) by paying the midwife. The women remain in their maternal home, living with their brothers, and property is passed matrilineally.[48] A similar form of matrilineal, de facto polyandry can be found in the institution of walking marriage among the Mosuo tribe of China.

Serial monogamy

Serial monogamy refers to remarriage after divorce or death of a spouse from a monogamous marriage, i.e. multiple marriages but only one legal spouse at a time (a series of monogamous relationships).[49]

According to Danish scholar Miriam K. Zeitzen, anthropologists treat serial monogamy, in which divorce and remarriage occur, as a form of polygamy as it also can establish a series of households that may continue to be tied by shared paternity and shared income.[38] As such, they are similar to the household formations created through divorce and serial monogamy.[50]

Serial monogamy creates a new kind of relative, the "ex-".[51] The "ex-wife", for example, can remain an active part of her "ex-husband's" life, as they may be tied together by legally or informally mandated economic support, which can last for years, including by alimony, child support, and joint custody. Bob Simpson, the British social anthropologist, notes that it creates an "extended family" by tying together a number of households, including mobile children. He says that Britons may have ex‑wives or ex‑brothers‑in‑law, but not an ex‑child. According to him, these "unclear families" do not fit the mold of the monogamous nuclear family.[52]

Group marriage

Group marriage is a non-monogamous marriage-like arrangement where three or more adults live together, all considering themselves partners, sharing finances, children, and household responsibilities. Polyamory is on a continuum of family-bonds that includes group marriage.[53] The term does not refer to bigamy as no claim to being married in formal legal terms is made.[54]

Scientific and prehistorical perspectives

Scientific studies classify humans as “mildly polygynous” or “monogamous with polygynous tendencies.”[18][19][20][21] As mentioned above, data from 1960 to 1980 in the Ethnographic Atlas Codebook indicated that polygamy was common.[55] A separate 1988 review examined the practices of 849 societies from before Western imperialism and colonization. The review found that 708 of the societies (83%) accepted polygyny. Only 16% were monogamous and 1% polyandrous.[56] Subsequent evidence in 2012 found that polyandry (in which women have multiple male partners) was likely in pre-history; it also identified 53 communities studied between 1912 and 2010 with either formal or informal polyandry, indicating that polyandry was more common worldwide than previously believed. The authors found that polyandry was most common in egalitarian societies, and suspected contributors to polyandry included fewer men (due to the existence or threat of high adult male mortality or absence/travel) and higher male contributions towards food production.[6] Polyandry still appears to occur in the minority of societies. Regardless of the type of polygamy, even when polygyny is accepted in the community, the majority of relationships in the society are monogamous in practice – while couples remain in the relationship, which may not be lifelong.[17] In many historical communities, serial monogamy may have been the accepted practice rather than a lifelong monogamous bond. How monogamy is defined when it comes to accepted sexual activity outside of the relationship, however, may differ by society.[17]

Recent anthropological data suggest that the modern concept of life-long monogamy has been in place for only the last 1,000 years.[57] Genetic evidence has demonstrated that a greater proportion of men began contributing to the genetic pool between 5,000–10,000 years ago, which suggests that reproductive monogamy became more common at that time.[24] This would correspond to the Neolithic agricultural revolution. During this time, formerly nomadic societies began to claim and settle land for farming, leading to the advent of property ownership and therefore inheritance. Men would therefore seek to ensure that their land would go to direct descendants and had a vested interest in limiting the sexual activities of their reproductive partners. It is possible that the concept of marriage and permanent monogamy evolved at this time.[25]

Other scientific arguments for monogamy prior to 2003 were based on characteristics of reproductive physiology, such as sperm competition,[58] sexual selection in primates,[59] and body size characteristics.[60] A 2019 synthesis of these and other data found that the weight of the evidence supports a mating bond that may include polygyny or polyandry, but is most likely to be predominantly serial monogamy.[17]

More recent genetic data has clarified that, in most regions throughout history, a smaller proportion of men contributed to human genetic history compared to women.[24][61] Assuming an equal number of men and women are born and survive to reproduce, this would indicate that historically, only a subset of men fathered children and did so with multiple women (and may suggest that many men either did not procreate or did not have children that survived to create modern ancestors). This circumstance could occur for several reasons, but there are three common interpretations:

- The first interpretation is a harem model, where one man will out-compete other men (presumably through acts of violence or power) for exclusive sexual access to a group of women. Groups of women could be related or unrelated. This does not seem to reflect real-world observations in more modern polygyny societies, where the majority of individuals seldom have more than one partner at a time.[17]

- Second, it may suggest that some men had either more sex or more reproductive success with multiple women simultaneously; this could be caused by sexual liaisons outside of a lifelong "monogamous" relationship (which may or may not be acceptable in their society), having multiple committed partners at once (polygyny), or simply sexual reproduction with multiple partners entirely outside of committed relationships (i.e., casual sex without relationships or pair-bonding).

- Third, it may suggest that some men were more likely than other men to have a series of monogamous relationships that led to children with different women throughout the man's life (serial monogamy).[17] There are a variety of explanations for this that range from the woman's decisions (the man's perceived attractiveness or ability to produce food) to the man's (social or coercive power).

The serial monogamy interpretation of genetic history would be congruent with other findings, such as the fact that humans form pair bonds (although not necessarily for life) and that human fathers invest in at least the early upbringing of their children.[17] Serial monogamy would also be consistent with the existence of a "honeymoon period", a period of intense interest in a single sexual partner (with less interest in other women) which may help to keep men invested in staying with the mother of their child for this period.[62] When reciprocated, this “honeymoon period” lasts 18 months to three years in most cases.[63][64] This would correspond to the period necessary to bring a child to relative independence in the traditionally small, interdependent, communal societies of pre-Neolithic humans, before they settled into agricultural communities.[24]

While genetic evidence typically displays a bias towards a smaller number of men reproducing with more women, some regions or time periods have shown the opposite. In a 2019 investigation, Musharoff et al. applied modern techniques to the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 high-coverage Complete Genomics whole-genome dataset.[65] They found that the Southern Han Chinese had a male bias (45% female, indicating that women were likely to reproduce with multiple men). This region is known for its lack of a concept of paternity and for a sense of female equality or superiority.[66] The Musharoff study also found a male bias in Europeans (20% female) during an out-of-Africa migration event that may have increased the number of men successfully reproducing with women, perhaps by replenishing the genetic pool in Europe. The study did confirm a more typical female bias in Yorubans (63% female), Europeans (84%), Punjabis (82%), and Peruvians (56%).[67]

Religious attitudes towards polygamy

Buddhism

Buddhism does not regard marriage as a sacrament; it is purely a secular affair. Normally Buddhist monks do not participate in it (though in some sects priests and monks do marry). Hence marriage receives no religious sanction.[68] Forms of marriage, in consequence, vary from country to country. The Parabhava Sutta states that "a man who is not satisfied with one woman and seeks out other women is on the path to decline". Other fragments in the Buddhist scripture seem to treat polygamy unfavorably, leading some authors to conclude that Buddhism generally does not approve of it[69] or alternatively regards it as a tolerated, but subordinate, marital model.[70]

Polygamy in Thailand was legally recognized until 1935. Polygamy in Myanmar was outlawed in 2015. In Sri Lanka, polyandry was legal in the kingdom of Kandy, but outlawed by British after conquering the kingdom in 1815.[68] When the Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese, the concubines of others were added to the list of inappropriate partners. Polyandry in Tibet was traditionally common, as was polygyny, and having several wives or husbands was never regarded as having sex with inappropriate partners.[71] Most typically, fraternal polyandry is practiced, but sometimes father and son have a common wife, which is a unique family structure in the world. Other forms of marriage are also present, like group marriage and monogamous marriage.[38] Polyandry (especially fraternal polyandry) is also common among Buddhists in Bhutan, Ladakh, and other parts of the Indian subcontinent.

Celtic traditions

Some pre-Christian Celtic pagans were known to practice polygamy, although the Celtic peoples wavered between it, monogamy and polyandry depending on the time period and the area.[72] In some areas this continued even after Christianization began, for instance the Brehon Laws of Gaelic Ireland explicitly allowed for polygamy,[73][74] especially amongst the noble class.[75] Some modern Celtic pagan religions accept the practice of polygamy to varying degrees,[76] though how widespread the practice is within these religions is unknown.

Christianity

Although the Old Testament describes numerous examples of polygamy among devotees to God, most Christian groups have rejected the practice of polygamy and have upheld monogamy alone as normative. Nevertheless, some Christians groups in different periods have practiced, or currently do practice, polygamy.[77][78] Some Christians actively debate whether the New Testament or Christian ethics allows or forbids polygamy.

Although the New Testament is largely silent on the subject of polygamy, some point to Jesus's repetition of the earlier scriptures, noting that a man and a wife "shall become one flesh".[79] However, some look to Paul's writings to the Corinthians: "Do you not know that he who is joined to a prostitute becomes one body with her? For, as it is written, 'The two will become one flesh.'" Supporters of polygamy claim that this verse indicates that the term refers to a physical, rather than a spiritual, union.[80]

Some Christian theologians[81] argue that in Matthew 19:3–9 and referring to Genesis 2:24,[82] Jesus explicitly states a man should have only one wife:

Have ye not read, that he which made them at the beginning made them male and female, And said, For this cause shall a man leave father and mother, and shall cleave to his wife: and they twain shall be one flesh?[83]

1 Timothy 3:2 states:

Now a bishop must be above reproach, married only once, temperate, sensible, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher,[84]

See verse 12 regarding deacons having only one wife. Similar counsel is repeated in the first chapter of the Epistle to Titus.[85]

Periodically, Christian reform movements that have sought to rebuild Christian doctrine based on the Bible alone (sola scriptura) have temporarily accepted polygyny as a Biblical practice. For example, during the Protestant Reformation, in a document which was simply referred to as "Der Beichtrat" (or "The Confessional Advice" ),[86] Martin Luther granted the Landgrave Philip of Hesse, who, for many years, had been living "constantly in a state of adultery and fornication",[87] a dispensation to take a second wife. The double marriage was to be done in secret, however, to avoid public scandal.[88] Some fifteen years earlier, in a letter to the Saxon Chancellor Gregor Brück, Luther stated that he could not "forbid a person to marry several wives, for it does not contradict Scripture." ("Ego sane fateor, me non posse prohibere, si quis plures velit uxores ducere, nec repugnat sacris literis.")[89]

In Sub-Saharan Africa, tensions have frequently erupted between advocates of the Christian insistence on monogamy and advocates of the traditional practice of polygamy. For instance, Mswati III, the Christian king of Eswatini, has 15 wives. In some instances in recent times, there have been moves for accommodation; in other instances, churches have strongly resisted such moves. African Independent Churches have sometimes referred to those parts of the Old Testament that describe polygamy in defense of the practice.

The illegality of polygamy in certain areas creates, according to certain Bible passages, additional arguments against it. Paul the Apostle writes "submit to the authorities, not only because of possible punishment but also because of conscience" (Romans 13:5), for "the authorities that exist have been established by God." (Romans 13:1) St Peter concurs when he says to "submit yourselves for the Lord's sake to every authority instituted among men: whether to the king, as the supreme authority, or to governors, who are sent by him to punish those who do wrong and to commend those who do right." (1 Peter 2:13,14) Pro-polygamists argue that, as long as polygamists currently do not obtain legal marriage licenses nor seek "common law marriage status" for additional spouses, no enforced laws are being broken any more than when monogamous couples similarly co-habitate without a marriage license.[90]

Roman Catholic Church

The Roman Catholic Church condemns polygamy; the Catechism of the Catholic Church lists it in paragraph 2387 under the head "Other offenses against the dignity of marriage" and states that it "is not in accord with the moral law." Also in paragraph 1645 under the head "The Goods and Requirements of Conjugal Love" states "The unity of marriage, distinctly recognized by our Lord, is made clear in the equal personal dignity which must be accorded to husband and wife in mutual and unreserved affection. Polygamy is contrary to conjugal love which is undivided and exclusive."[91]

Saint Augustine saw a conflict with Old Testament polygamy. He refrained from judging the patriarchs, but did not deduce from their practice the ongoing acceptability of polygyny. On the contrary, he argued that the polygamy of the Fathers, which was tolerated by the Creator because of fertility, was a diversion from His original plan for human marriage. Augustine wrote: "That the good purpose of marriage, however, is better promoted by one husband with one wife, than by a husband with several wives, is shown plainly enough by the very first union of a married pair, which was made by the Divine Being Himself."[92]

Augustine taught that the reason patriarchs had many wives was not because of fornication, but because they wanted more children. He supported his premise by showing that their marriages, in which husband was the head, were arranged according to the rules of good management: those who are in command (quae principantur) in their society were always singular, while subordinates (subiecta) were multiple. He gave two examples of such relationships: dominus-servus – master-servant (in older translation: slave) and God-soul. The Bible often equates worshiping multiple gods, i.e. idolatry to fornication.[93] Augustine relates to that: "On this account there is no True God of souls, save One: but one soul by means of many false gods may commit fornication, but not be made fruitful."[94]

As tribal populations grew, fertility was no longer a valid justification of polygamy: it "was lawful among the ancient fathers: whether it be lawful now also, I would not hastily pronounce (utrum et nunc fas sit, non temere dixerim). For there is not now necessity of begetting children, as there then was, when, even when wives bear children, it was allowed, in order to a more numerous posterity, to marry other wives in addition, which now is certainly not lawful."[95]

Augustine saw marriage as a covenant between one man and one woman, which may not be broken. It was the Creator who established monogamy: "Therefore, the first natural bond of human society is man and wife."[96] Such marriage was confirmed by the Saviour in the Gospel of Matthew (Mat 19:9) and by His presence at the wedding in Cana (John 2:2).[97] In the Church—the City of God—marriage is a sacrament and may not and cannot be dissolved as long as the spouses live: "But a marriage once for all entered upon in the City of our God, where, even from the first union of the two, the man and the woman, marriage bears a certain sacramental character, can in no way be dissolved but by the death of one of them."[98] In chapter 7, Augustine pointed out that the Roman Empire forbad polygamy, even if the reason of fertility would support it: "For it is in a man's power to put away a wife that is barren, and marry one of whom to have children. And yet it is not allowed; and now indeed in our times, and after the usage of Rome (nostris quidem iam temporibus ac more Romano), neither to marry in addition, so as to have more than one wife living." Further on he notices that the Church's attitude goes much further than the secular law regarding monogamy: It forbids remarrying, considering such to be a form of fornication: "And yet, save in the City of our God, in His Holy Mount, the case is not such with the wife. But, that the laws of the Gentiles are otherwise, who is there that knows not."[99]

The Council of Trent condemns polygamy: "If anyone saith, that it is lawful for Christians to have several wives at the same time, and that this is not prohibited by any divine law; let him be anathema."[100]

In modern times a minority of Roman Catholic theologians have argued that polygamy, though not ideal, can be a legitimate form of Christian marriage in certain regions, in particular Africa.[101][102] The Roman Catholic Church teaches in its Catechism that:

polygamy is not in accord with the moral law. [Conjugal] communion is radically contradicted by polygamy; this, in fact, directly negates the plan of God that was revealed from the beginning, because it is contrary to the equal personal dignity of men and women who in matrimony give themselves with a love that is total and therefore unique and exclusive.[103]

Lutheran Church

The Lutheran World Federation hosted a regional conference in Africa, in which the acceptance of polygamists into full membership by the Lutheran Church in Liberia was defended as being permissible.[104] The Lutheran Church in Liberia, however, does not permit polygamists who have become Christians to marry more wives after they have received the sacrament of Holy Baptism.[105] Evangelical Lutheran missionaries in Maasai also tolerate the practice of polygamy and in Southern Sudan, some polygamists are becoming Lutheran Christians.[106]

Anglican Communion

The 1988 Lambeth Conference of the Anglican Communion ruled that polygamy was permissible in certain circumstances:[107]

The Conference upholds monogamy as God's plan, as the idea of relationship of love between husband and wife; nevertheless recommends that a polygamist who responds to the Gospel and wishes to join the Anglican Church may be baptized and confirmed with his believing wives and children on the following conditions:

- that the polygamist shall promise not to marry again as long as any of his wives at the time of his conversion are alive;

- that the receiving of such a polygamist has the consent of the local Anglican community;

- that such a polygamist shall not be compelled to put away any of his wives on account of the social deprivation they would suffer.[107]

Latter Day Saint movement

| Mormonism and polygamy |

|---|

.png.webp) |

|

|

In accordance with what Joseph Smith indicated was a revelation, the practice of plural marriage, the marriage of one man to two or more women, was instituted among members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the early 1840s.[108] Despite Smith's revelation, the 1835 edition of the 101st Section of the Doctrine and Covenants, written after the doctrine of plural marriage began to be practiced, publicly condemned polygamy. This scripture was used by John Taylor in 1850 to quash Mormon polygamy rumors in Liverpool, England.[109] Polygamy was made illegal in the state of Illinois[110] during the 1839–44 Nauvoo era when several top Mormon leaders, including Smith,[111][112] Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball took multiple wives. Mormon elders who publicly taught that all men were commanded to enter plural marriage were subject to harsh discipline.[113] On 7 June 1844 the Nauvoo Expositor criticized Smith for plural marriage.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church)

After Joseph Smith was killed by a mob on 27 June 1844, the main body of Latter Day Saints left Nauvoo and followed Brigham Young to Utah where the practice of plural marriage continued.[114] In 1852, Brigham Young, the second president of the LDS Church, publicly acknowledged the practice of plural marriage through a sermon he gave. Additional sermons by top Mormon leaders on the virtues of polygamy followed.[115]: 128 Controversy followed when polygamy became a social cause, writers began to publish works condemning polygamy. The key plank of the Republican Party's 1856 platform was "to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism, polygamy and slavery".[116] In 1862, Congress issued the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act which clarified that the practice of polygamy was illegal in all US territories. The LDS Church believed that their religiously based practice of plural marriage was protected by the United States Constitution,[117] however, the unanimous 1878 Supreme Court decision Reynolds v. United States declared that polygamy was not protected by the Constitution, based on the longstanding legal principle that "laws are made for the government of actions, and while they cannot interfere with mere religious belief and opinions, they may with practices."[118]

Increasingly harsh anti-polygamy legislation in the US led some Mormons to emigrate to Canada and Mexico. In 1890, LDS Church president Wilford Woodruff issued a public declaration (the Manifesto) announcing that the LDS Church had discontinued new plural marriages. Anti-Mormon sentiment waned, as did opposition to statehood for Utah. The Smoot Hearings in 1904, which documented that the LDS Church was still practicing polygamy spurred the LDS Church to issue a Second Manifesto again claiming that it had ceased performing new plural marriages. By 1910 the LDS Church excommunicated those who entered into, or performed, new plural marriages. Even so, many plural husbands and wives continued to cohabit until their deaths in the 1940s and 1950s.[119]

Enforcement of the 1890 Manifesto caused various splinter groups to leave the LDS Church in order to continue the practice of plural marriage.[120] Polygamy among these groups persists today in Utah and neighboring states as well as in the spin-off colonies. Polygamist churches of Mormon origin are often referred to as "Mormon fundamentalist" churches even though they are not parts of the LDS Church. Such fundamentalists often use a purported 1886 revelation to John Taylor as the basis for their authority to continue the practice of plural marriage.[121] The Salt Lake Tribune stated in 2005 that there were as many as 37,000 fundamentalists with less than half of them living in polygamous households.[122]

On 13 December 2013, US Federal Judge Clark Waddoups ruled in Brown v. Buhman that the portions of Utah's anti-polygamy laws which prohibit multiple cohabitation were unconstitutional, but also allowed Utah to maintain its ban on multiple marriage licenses.[123][124][125][126] Unlawful cohabitation, where prosecutors did not need to prove that a marriage ceremony had taken place (only that a couple had lived together), had been the primary tool used to prosecute polygamy in Utah since the 1882 Edmunds Act.[119]

Mormon fundamentalism

The Council of Friends (also known as the Woolley Group and the Priesthood Council)[127][128] was one of the original expressions of Mormon fundamentalism, having its origins in the teachings of Lorin C. Woolley, a dairy farmer excommunicated from the LDS Church in 1924. Several Mormon fundamentalist groups claim lineage through the Council of Friends, including but not limited to, the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS Church), the Apostolic United Brethren, the Centennial Park group, the Latter Day Church of Christ, and the Righteous Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Community of Christ

The Community of Christ, known as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church) prior to 2001, has never sanctioned polygamy since its foundation in 1860. Joseph Smith III, the first Prophet-President of the RLDS Church following the reorganization of the Church, was an ardent opponent of the practice of plural marriage throughout his life. For most of his career, Smith denied that his father had been involved in the practice and insisted that it had originated with Brigham Young. Smith served many missions to the western United States, where he met with and interviewed associates and women claiming to be widows of his father, who attempted to present him with evidence to the contrary. Smith typically responded to such accusations by saying that he was "not positive nor sure that [his father] was innocent",[129] and that if, indeed, the elder Smith had been involved, it was still a false practice. However, many members of the Community of Christ and some of the groups that were previously associated with it are not convinced that Joseph Smith practiced plural marriage and they believe that the evidence which indicates that he practiced it is flawed.[130][131]

Hinduism

The Rigveda mentions that during the Vedic period, a man could have more than one wife.[132] The practice is attested in epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The Dharmashastras permit a man to marry women provided that the first wife agree to marry him. Despite its existence, it was most usually practiced by men of higher status. Common people were only allowed a second marriage if the first wife could not bear a son or have some dispute because there is no law for divorce in Hinduism.[133]

According to the Vishnu Smriti, the number of wives one could have is linked to one's social class, referred to as varna:

Now a Brāhmaṇa may take many wives in the direct order of the (four) knowledge;

A Kshatriya means warrior knowledge, three;

A Vaishya means business knowledge, two;

A Shudra means cleaning knowledge, one only[134]

This linkage of the number of permitted wives to the varna system is also supported by the Baudhayana Dharmasutra and the Paraskara Grihyasutra.[135][136]

The Apastamba Dharmasutra and the Manusmriti allow marriage to a second wife if the first one is unable to discharge her religious duties or is unable to bear a child or have any dispute because in Hinduism there was no law for divorce.[135]

For a Brahmana, only one wife could rank as the chief consort who performed the religious rites (dharma-patni) along with the husband. The chief consort had to be of an equal knowledge. If a man married several women from the same knowledgeable, then the eldest wife held the position of the chief consort.[137] Hindu kings commonly had more than one wife and are regularly attributed four wives by the scriptures. They were: Mahisi, who was the chief consort, Parivrkti, who had no son, Vaivata, who is considered the favorite wife and the Palagali, who was the daughter of the last of the court officials.[132]

Traditional Hindu law allowed polygamy if the first wife could not bear a child.[138]

The Hindu Marriage Act was enacted in 1955 by the Indian Parliament and made polygamy illegal for everyone in India except for Muslims. Prior to 1955, polygamy was permitted for Hindus. Marriage laws in India are dependent upon the religion of the parties in question.[139]

Islam

In Islamic marital jurisprudence, under reasonable and warranted conditions, a Muslim man may have more than one wife at the same time, up to a total of four. Muslim women are not permitted to have more than one husband at the same time under any circumstances.

Based on verse 30:21 of Quran the ideal relationship is the comfort that a couple find in each other's embrace:

And one of His signs is that He created for you spouses from among yourselves so that you may find comfort in them. And He has placed between you compassion and mercy. Surely in this are signs for people who reflect.

The polygyny that is allowed in the Quran is for special situations. There are strict requirements to marrying more than one woman, as the man must treat them fairly financially and in terms of support given to each wife, according to Islamic law. However, Islam advises monogamy for a man if he fears he cannot deal justly with his wives. This is based on verse 4:3 of Quran which says:

If you fear you might fail to give orphan women their ˹due˺ rights ˹if you were to marry them˺, then marry other women of your choice—two, three, or four. But if you are afraid you will fail to maintain justice, then ˹content yourselves with˺ one or those ˹bondwomen˺ in your possession. This way you are less likely to commit injustice.

Muslim women are not allowed to marry more than one husband at once. However, in the case of a divorce or their husbands' death they can remarry after the completion of Iddah, as divorce is legal in Islamic law. A non-Muslim woman who flees from her non-Muslim husband and accepts Islam has the option to remarry without divorce from her previous husband, as her marriage with non-Muslim husband is Islamically dissolved on her fleeing.[140] A non-Muslim woman captured during war by Muslims, can also remarry, as her marriage with her non-Muslim husband is Islamically dissolved at capture by Muslim soldiers.[141][142] This permission is given to such women in verse 4:24 of Quran. The verse also emphasizes on transparency, mutual agreement and financial compensation as prerequisites for matrimonial relationship as opposed to prostitution; it says:

Also ˹forbidden are˺ married women—except ˹female˺ captives in your possession. This is Allah’s commandment to you. Lawful to you are all beyond these—as long as you seek them with your wealth in a legal marriage, not in fornication. Give those you have consummated marriage with their due dowries. It is permissible to be mutually gracious regarding the set dowry. Surely Allah is All-Knowing, All-Wise.

Muhammad was monogamously married to Khadija, his first wife, for 25 years, until she died. After her death, he married multiple women. Muhammad had a total of 9 wives at the same time, even though Muslim men were limited to 4 wives. His total wives are 11.

One reason cited for polygyny is that it allows a man to give financial protection to multiple women, who might otherwise not have any support (e.g. widows).[143] However, some Islamic scholars say the wife can set a condition, in the marriage contract, that the husband cannot marry another woman during their marriage. In such a case, the husband cannot marry another woman as long as he is married to his wife. However, other Islamic scholars state that this condition is not allowed.[144] According to traditional Islamic law, each of those wives keeps their property and assets separate; and are paid Mahr separately by their husband. Usually the wives have little to no contact with each other and lead separate, individual lives in their own houses, and sometimes in different cities, though they all share the same husband.

In most Muslim-majority countries, polygyny is legal with Kuwait being the only one where no restrictions are imposed on it. The practice is illegal in Muslim-majority Turkey, Tunisia, Albania, Kosovo, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brunei, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan , Uzbekistan, Tajikistan.[145][146][147][148]

Countries that allow polygyny typically also require a man to obtain permission from his previous wives before marrying another, and require the man to prove that he can financially support multiple wives. In Malaysia and Morocco, a man must justify taking an additional wife at a court hearing before he is allowed to do so.[149] In Sudan, the government encouraged polygyny in 2001 to increase the population.[150]

Judaism

The Torah contains a few specific regulations that apply to polygamy,[151] such as Exodus 21:10: "If he take another wife for himself; her food, her clothing, and her duty of marriage, shall he not diminish".[152] Deuteronomy 21:15–17, states that a man must award the inheritance due to a first-born son to the son who was actually born first, even if he hates that son's mother and likes another wife more;[153] and Deuteronomy 17:17 states that the king shall not have too many wives.[154] Despite its prevalence in the Hebrew Bible, some scholars do not believe that polygyny was commonly practiced in the biblical era because it required a significant amount of wealth.[155] Michael Coogan (and others), in contrast, states that "Polygyny continued to be practiced well into the biblical period, and it is attested among Jews as late as the second century CE".[156][157][158]

The Dead Sea Scrolls show that several smaller Jewish sects forbade polygamy before and during the time of Jesus.[159][160][161] The Temple Scroll (11QT LVII 17–18) seems to prohibit polygamy.[160][162] The rabbinical era that began with the destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE saw a continuation of some degree of legal acceptance for polygamy. In the Babylonian Talmud (BT), Kiddushin 7a, its states, "Raba said: [If a man declares,] 'Be thou betrothed to half of me,' she is betrothed: 'half of thee be betrothed to me,' she is not betrothed."[163] The BT during a discussion of Levirate marriage in Yevamot 65a appears to repeat the precedent found in Exodus 21:10: "Raba said: a man may marry wives in addition to the first wife; provided only that he possesses the means to maintain them".[164] The Jewish Codices began a process of restricting polygamy in Judaism.

Most notable in the rabbinic period on the issue of polygamy, though more specifically for Ashkenazi Jews, was the synod of Rabbeinu Gershom. About 1000 CE he called a synod which decided the following particulars: (1) prohibition of polygamy; (2) necessity of obtaining the consent of both parties to a divorce; (3) modification of the rules concerning those who became apostates under compulsion; (4) prohibition against opening correspondence addressed to another.[165][166][158] Some Sephardic Jews such as Abraham David Taroç, were known to have several wives.

Polygamy was common among Jewish communities in the Levant, possibly due to the influence of Muslim society, with 17% of divorce claims by women being due to complaints over husbands taking additional wives. According to R. Joseph Karo (16th century author of the last great codification of Jewish law, the Shulchan Aruch), and many other rabbis from Safed, the ban of Rabbeinu Gershom had expired, and therefore even Ashkenazim could marry additional wives. Even in instances where the husband made prenuptial agreements not to marry additional wives, local rabbis found loopholes to allow them to do so anyway.[167][168]

The assembly led by Rabbeinu Gershom instituted a ban on polygamy, but this ban was not well received by the Sephardic communities. In addition to the ban, Gershon also introduced a law called Heter meah rabbanim which allows the men to remarry with the permission from one hundred rabbis from different countries.

In the modern day, polygamy is generally not condoned by Jews.[169][170] Ashkenazi Jews have continued to follow Rabbenu Gershom's ban since the 11th century.[171] Some Mizrahi Jewish communities (particularly Yemenite Jews and Persian Jews) discontinued polygyny more recently, after they immigrated to countries where it was forbidden or illegal. Israel prohibits polygamy by law.[172][173][174][175] In practice, however, the law is loosely enforced, primarily to avoid interference with Bedouin culture, where polygyny is practiced.[176] Pre-existing polygynous unions among Jews from Arab countries (or other countries where the practice was not prohibited by their tradition and was not illegal) are not subject to this Israeli law. But Mizrahi Jews are not permitted to enter into new polygamous marriages in Israel. However polygamy may still occur in non-European Jewish communities that exist in countries where it is not forbidden, such as Jewish communities in Iran and Morocco.

Former chief rabbi Ovadia Yosef has come out in favor of legalizing polygamy and the practice of pilegesh (concubine) by the Israeli government.[177] Tzvi Zohar, a professor from the Bar-Ilan University, recently suggested that based on the opinions of leading halachic authorities, the concept of concubines may serve as a practical halachic justification for premarital or non-marital cohabitation.[178][179]

Zoroastrianism

There is limited information about polygamy in Zoroastrian tradition. There is no passage in the Avesta that favors polygamy or monogamy.[180] However, tradition holds that Zoroaster had three wives.[181][182] Polygamy appears to have been a right of spiritual dignitaries and aristocrats.[183] It is mentioned in foreign writings, such as the letter of Tansar.[184]

For those who were the most virtuous and pious, he chose out princesses, that all might desire virtue and chastity. He was content with one or two wives for himself, and disapproved of having many children, saying: to have many children is fitting for the populace, but kings and nobles take pride in the smallness of their families

— Tansar

It was also written about in the 4th century CE by the Roman soldier and historian Ammianus Marcellinus, writing about Zoroastrian communities.[185]

Each man according to his means contracts many or few marriages, whence their affection, divided as it is among various objects, grows cold.

— Ammianus Marcellinus

Legal status

- In India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Singapore, polygamy is only legal for Muslims.

- In Nigeria and South Africa, polygamous marriages under customary law and for Muslims are legally recognized.

International law

In 2000, the United Nations Human Rights Committee reported that polygamy violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), citing concerns that the lack of "equality of treatment with regard to the right to marry" meant that polygamy, restricted to polygyny in practice, violates the dignity of women and should be outlawed.[186] Specifically, reports to UN Committees have noted violations of ICCPR due to these inequalities,[187] and reports to the UN General Assembly have recommended it be outlawed.[188][189]

ICCPR does not apply to countries that have not signed it, which includes many Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Malaysia, Brunei, Oman, and South Sudan.[190]

Canada

Canada has taken a strong stand against polygamy, and the Canadian Department of Justice has argued that polygyny is a violation of International Human Rights Law, as a form of gender discrimination.[191] In Canada, the federal Criminal Code applies throughout the country. It extends the definition of polygamy to having any kind of conjugal union with more than one person at the same time. Also anyone who assists, celebrates, or is a part to a rite, ceremony, or contract that sanctions a polygamist relationship is guilty of polygamy. Polygamy is an offence punishable by up to five years in prison. In 2017, two Canadian religious leaders were found guilty of practicing polygamy by the Supreme Court of British Columbia.[192] Both of them are former bishops of the Mormon denomination of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS).[192]

Russia

Polygamous marriages are not recognized in the Russian Federation. The Family Code of Russia states that a marriage can only be contracted between a man and a woman, neither of whom is married to someone else.[193] Furthermore, Russia does not recognize polygamous marriages that had been contracted in other countries.[194] Under Russian law, de facto polygamy or multiple cohabitation in and of itself is not a crime.[195]

Due to the imbalance between urban educated women and men in predominantly Mongol-inhabited regions of Russia men sometimes may have multiple women as wives one report claims.[196] This sometimes results in households that are openly de facto polygamous.United Kingdom

Bigamy is illegal in the United Kingdom.[197] De facto polygamy (having multiple partners at the same time) is not a criminal offence, provided the person does not register more than one marriage at the same time. In the UK, adultery is not a criminal offence (it is only a ground for divorce[198]). In a written answer to the House of Commons, "In Great Britain, polygamy is only recognized as valid in law in circumstances where the marriage ceremony has been performed in a country whose laws permit polygamy and the parties to the marriage were domiciled there at the time. In addition, immigration rules have generally prevented the formation of polygamous households in this country since 1988."[199]

The 2010 UK government decided that Universal Credit (UC), which replaces means-tested benefits and tax credits for working-age people and will not be completely introduced until 2021, will not recognize polygamous marriages. A House of Commons briefing paper states "Treating second and subsequent partners in polygamous relationships as separate claimants could in some situations mean that polygamous households receive more under Universal Credit than they do under the current rules for means-tested benefits and tax credits. This is because, as explained above, the amounts which may be paid in respect of additional spouses are lower than those which generally apply to single claimants." There is currently no official statistics data on cohabiting polygamous couples who have arranged marriage in religious ceremonies.[200]

United States

Polygamy is illegal in all 50 states in the U.S. In the state of Utah it currently remains a controversial issue that has been subject to legislative battles throughout the years. As of 2020 Utah is the only state where the practice is designated as an infraction rather than the more serious designation as a crime. However, recognizing polygamous unions is still illegal under the Constitution of Utah.[201] Federal legislation to outlaw the practice was endorsed as constitutional in 1878 by the Supreme Court in Reynolds v. United States, despite the religious objections of Mormonism's largest denomination the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). The LDS Church subsequently ended the practice of polygamy around the turn of the twentieth century;[202] however, several smaller fundamentalist Mormon groups across the state (not associated with the mainstream Church) continue the practice.

On 13 December 2013, a federal judge, spurred by the American Civil Liberties Union and other groups,[203] struck down the parts of Utah's bigamy law that criminalized cohabitation, while also acknowledging that the state may still enforce bans on having multiple marriage licenses.[204] This decision was overturned by the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, thus effectively recriminalizing polygamy as a felony.[205] In 2020, Utah voted to downgrade polygamy from a felony to an infraction, but it remains a felony if force, threats or other abuses are involved.[206]

Prosecutors in Utah have long had a policy of not pursuing polygamy in the absence of other associated crimes (e.g. fraud, abuse, marriage of underage persons, etc.).[207][208] There are about 30,000 people living in polygamous communities in Utah.[209]

Individualist feminism and advocates such as Wendy McElroy and journalist Jillian Keenan support the freedom for adults to voluntarily enter polygamous marriages.[210][211]

Authors such as Alyssa Rower and Samantha Slark argue that there is a case for legalizing polygamy on the basis of regulation and monitoring of the practice, legally protecting the polygamous partners and allowing them to join mainstream society instead of forcing them to hide from it when any public situation arises.[212][213]

In an October 2004 op-ed for USA Today, George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley argued that, as a simple matter of equal treatment under the law, polygamy ought to be legal. Acknowledging that underage girls are sometimes coerced into polygamous marriages, Turley replied that "banning polygamy is no more a solution to child abuse than banning marriage would be a solution to spousal abuse".[214]

Stanley Kurtz, a conservative fellow at the Hudson Institute, rejects the decriminalization and legalization of polygamy. He stated:

Marriage, as its ultramodern critics would like to say, is indeed about choosing one's partner, and about freedom in a society that values freedom. But that's not the only thing it is about. As the Supreme Court justices who unanimously decided Reynolds in 1878 understood, marriage is also about sustaining the conditions in which freedom can thrive. Polygamy in all its forms is a recipe for social structures that inhibit and ultimately undermine social freedom and democracy. A hard-won lesson of Western history is that genuine democratic self-rule begins at the hearth of the monogamous family.[215]

In January 2015, Pastor Neil Patrick Carrick of Detroit, Michigan, brought a case (Carrick v. Snyder) against the State of Michigan that the state's ban of polygamy violates the Free Exercise and Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution.[216][217] The case was dismissed with prejudice on 10 February 2016, for lack of standing.[218]

Indonesia

Indonesia is the most populous Muslim country. Most of the polygamy families come from Muslim family, also come from aristocrats, registered civil servants, Islamic students (santri), and wholesalers.[219][220]

Constitutionally, Indonesia (basically) only recognize monogamy. But, government allows polygamy in some conditions:

- The wife cannot carry out her obligations as a wife.

- The wife has a physical disability or an incurable disease.

- The wife cannot bear children.

There are other requirements for registered civil servants.[221][222]

Post-war Germany plans

In Nazi Germany, there was an effort by Martin Bormann and Heinrich Himmler to introduce new legislation concerning plural marriage.[223] The argument ran that after the war, 3 to 4 million women would have to remain unmarried due to the great number of soldiers fallen in battle. In order to make it possible for these women to have children, a procedure for application and selection for suitable men (i.e. decorated war heroes) to enter a marital relationship with an additional woman was planned.[223] The privileged position of the first wife was to be secured by awarding her the title Domina.[223]

The greatest fighter deserves the most beautiful woman ... If the German man is to be unreservedly ready to die as a soldier, he must have the freedom to love unreservedly. For struggle and love belong together. The philistine should be glad if he gets whatever is left

— Adolf Hitler[223]

See also

Notes

- For the extent to which states can and do recognize potentially and actual polygamous forms as valid, see Conflict of marriage laws.

References

- Harper, Douglas. "polygamy". Online Etymology Dictionary. "Polygamy | Etymology, origin and meaning of polygamy by etymonline". Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- πολυγαμία. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- "πολυγαμία". Dictionary of Standard Modern Greek (in Greek). Center for the Greek Language. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016.

- Babiniotis, Georgios (2002). "s.v. πολυγαμία". Dictionary of Modern Greek (in Greek). Lexicology Centre.

- Ethnographic Atlas Codebook Archived 18 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine derived from George P. Murdock's Ethnographic Atlas recording the marital composition of 1231 societies from 1960 to 1980

- Starkweather, Katherine; Hames, Raymond (2012). "A Survey of Non‑Classical Polyandry". Human Nature. 23 (2): 149–72. doi:10.1007/s12110-012-9144-x. eISSN 1936-4776. ISSN 1045-6767. OCLC 879353439. PMID 22688804. S2CID 2008559. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- Golomski, Casey (6 January 2016). Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies – via ResearchGate.

- Kramer, Stephanie (7 December 2020). "Polygamy is rare around the world". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- Reichard, Ulrich H. (2003). "Monogamy: past and present". In Reichard, Ulrich H.; Boesch, Christophe (eds.). Monogamy: Mating Strategies and Partnerships in Birds, Humans and Other Mammals. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–25. ISBN 978-0-521-52577-0. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Low B.S. (2003) Ecological and social complexities in human monogamy Archived 2018-07-13 at the Wayback Machine. Monogamy: Mating Strategies and Partnerships in Birds, Humans and Other Mammals:161–176.

- Sheff, Elisabeth (22 July 2014). "Seven Forms of Non-Monogamy". Psychology Today.

- Cf. "Monogamy" in Britannica World Language Dictionary, R.C. Preble (ed.), Oxford-London 1962, p. 1275:1. The practice or principle of marrying only once. opp. to digamy now rare 2. The condition, rule or custom of being married to only one person at a time (opp. to polygamy or bigamy) 1708. 3. Zool. The habit of living in pairs, or having only one mate; The same text repeats The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, W. Little, H.W. Fowler, J. Coulson (ed.), C.T. Onions (rev. & ed.,) Oxford 1969, 3rd edition, vol.1, p.1275; OED Online. March 2010. Oxford University Press. 23 Jun. 2010 Cf. Monogamy Archived 2015-06-23 at the Wayback Machine in Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- Kramer, Karen L.; Russell, Andrew F. (2014). "Kin-selected cooperation without lifetime monogamy: human insights and animal implications". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier BV. 29 (11): 600–606. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.001. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 25267298.

- Schacht, Ryan N. (2013), Cassava and the Makushi: A Shared History of Resiliency and Transformation, Bloomsbury, T&T Clark, pp. 15–30, doi:10.5040/9781350042162.ch-001, ISBN 9781350042162

- Beckerman, Stephen; Valentine, Paul (2002). Cultures of Multiple Fathers. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2456-0.

- Hennigh, Lawrence (1 January 1970). "Functions and Limitations of Alaskan Eskimo Wife Trading". Arctic. The Arctic Institute of North America. 23 (1). doi:10.14430/arctic3151. ISSN 1923-1245.

- Schacht, Ryan; Kramer, Karen (19 July 2019). "Are We Monogamous? A Review of the Evolution of Pair-Bonding in Humans and Its Contemporary Variation Cross-Culturally". Front. Ecol. Evol. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00230.

- Brown, Gillian R.; Laland, Kevin N.; Mulder, Monique Borgerhoff (2009). "Bateman's principles and human sex roles". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier BV. 24 (6): 297–304. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.005. ISSN 0169-5347. PMC 3096780. PMID 19403194. S2CID 5935377.

- Frost, Peter (2008). "Sexual selection and human geographic variation". Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA). 2 (4): 169–191. doi:10.1037/h0099346. ISSN 1933-5377.

- Low, Bobbi S. (4 January 2015). Why Sex Matters. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16388-8.

- Scheidel, Walter (2008). "Monogamy and Polygyny in Greece, Rome, and World History". SSRN Electronic Journal. Elsevier BV. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1214729. ISSN 1556-5068.

- Lippold, Sebastian; Xu, Hongyang; Ko, Albert; Li, Mingkun; Renaud, Gabriel; Butthof, Anne; Schröder, Roland; Stoneking, Mark (24 September 2014). "Human paternal and maternal demographic histories: insights from high-resolution Y chromosome and mtDNA sequences". Investigative Genetics. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 5 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-5-13. ISSN 2041-2223. PMC 4174254. PMID 25254093. S2CID 16464327.

- Sample, Ian (24 September 2014). "More women than men have added their DNA to the human gene pool". the Guardian. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- Dupanloup, Isabelle; Pereira, Luisa; Bertorelle, Giorgio; Calafell, Francesc; Prata, Maria; Amorim, Antonio; Barbujani, Guido; et al. (2003). "A recent shift from polygyny to monogamy in humans is suggested by the analysis of worldwide Y-chromosome diversity". J Mol Evol. 57 (1): 85–97. Bibcode:2003JMolE..57...85D. doi:10.1007/s00239-003-2458-x. PMID 12962309. S2CID 2673314.

- Goody, Jack (1976). Production and Reproduction: A Comparative Study of the Domestic Domain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- "British & World English: sharia". Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "Islam". HISTORY. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- John L. Esposito, ed. (2014). "Islamic Law". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- Vikør, Knut S. (2014). "Sharīʿah". In Emad El-Din Shahin (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 4 June 2014.

- Calder, Norman (2009). "Law. Legal Thought and Jurisprudence". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Many Wives, Many Powers: Authority and Power in Polygynous Families. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. 1970. p. 17. ISBN 9780810102705.

- Fenske, James (9 November 2013). "African polygamy: Past and present". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Henrich, Joseph; Boyd, Robert; Richerson, Peter J. (5 March 2012). "The puzzle of monogamous marriage". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 367 (1589): 657–669. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0290. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3260845. PMID 22271782.

- Kramer, Stephanie. "Polygamy is rare around the world and mostly confined to a few regions".

- Goody, Jack (1974). "Polygyny, Economy and the Role of Women". The Character of Kinship. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–190. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511621697.014. ISBN 9780521202909.

- White, Douglas; Burton, Michael (December 1988). "Causes of Polygyny: Ecology, Economy, Kinship, and Warfare". American Anthropologist. 90 (4): 871–887. doi:10.1525/aa.1988.90.4.02a00060.

- Fenske, James (November 2012). "African polygamy: past and present" (PDF). Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford. pp. 1–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- Zeitzen, Miriam Koktvedgaard (2008). Polygamy: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 978-1-84520-220-0.

- Lee, Gary R. (1982). "Structural Variety in Marriage". Family Structure and Interaction: A Comparative Analysis (2nd, revised ed.). University of Minnesota Press. pp. 92–93.

- Herlihy, David (1984). McNetting, Robert; Will, Richard; Arnould, Eric (eds.). Households: Comparative and Historical Studies of the Domestic Group. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 393–395.

- Baloyi, Elijah M. (August 2013). "Critical reflections on polygamy in the African Christian context". Missionalia. 41 (2): 164–181. doi:10.7832/41-2-12. hdl:10500/29386. ISSN 0256-9507.

- Fox, Robin (1967). Kinship and Marriage. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. p. 39.

- "Gender Equality and Social Institutions in Gabon". Social Institutions & Gender Index, genderindex.org. 2007. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- Stone, Linda (2006). Kinship and Gender. Westview. ISBN 9780813348629.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1978). "Pahari and Tibetan Polyandry Revisited". Ethnology. 17 (3): 325–337. doi:10.2307/3773200. JSTOR 3773200.

- Levine, Nancy (1998). The Dynamics of polyandry: kinship, domesticity, and population on the Tibetan border. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- "Nayar – Marriage and Family".

- Gough, E. Kathleen (1959). "The Nayars and the Definition of Marriage". Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 89 (1): 23–34. doi:10.2307/2844434. JSTOR 2844434.

- Fisher, Helen (2000). The First Sex. Ballantine Books. pp. 271–72, 276. ISBN 978-0-449-91260-7.

- FALEN, DOUGLAS J. (23 October 2009). "Polygamy: a cross-cultural analysis by Zeitzen, Miriam Koktvedgaard". Social Anthropology. 17 (4): 510–511. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8676.2009.00088_20.x. ISSN 0964-0282.

- For a popular press angle, see e.g. Rosie Wilby, Is Monogamy Dead?: Rethinking Relationships in the 21st Century (Cardiff: Accent Press, 2017), 107. ISBN 9781786154521. For deeper, scholarly analysis, see e.g. David Silverman, "The Construction of 'Delicate' Objects in Counselling", in ed. Margaret Wetherell et al., Discourse Theory and Practice: A Reader (London: Sage, 2001), 123–27. ISBN 9780761971566

- Simpson, Bob (1998). Changing Families: An Ethnographic Approach to Divorce and Separation. Oxford: Berg.

- "Polyamory", in Robert T. Francoeur and Raymond J. Noonan, eds., The Continuum Complete International Encyclopedia of Sexuality (London: A&C Black, 2004), 1205. ISBN 9780826414885

- Constantine, Larry L. (1974). Group Marriage: A Study of Contemporary Multilateral Marriage. Collier Books. ISBN 978-0020759102.

- Murdock GP (1981) Atlas of World Cultures. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press

- White, Douglas; Betzig, Laura; Mulder, Monique (1 August 1988). "Rethinking Polygyny: Co-Wives, Codes, and Cultural Systems [and Comments and Reply]". Current Anthropology. JSTOR 2743506. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- Zimmer, Carl (2 August 2013). "Monogamy and Human Evolution". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- Anderson, M. J.; Dixson, A. F. (2002). "Sperm competition: motility and the midpiece in primates". Nature. 416 (6880): 496. Bibcode:2002Natur.416..496A. doi:10.1038/416496a. PMID 11932733. S2CID 4388134.

- Dixson, A. L.; Anderson, M. J. (2002). "Sexual selection, seminal coagulation and copulatory plug formation in primates". Folia Primatol. 73 (2–3): 63–69. doi:10.1159/000064784. PMID 12207054. S2CID 46804812.

- Harcourt, A. H.; Harvey, P. H.; Larson, S. G.; Short, RV (1981). "Testis weight, body weight and breeding system in primates". Nature. 293 (5827): 55–57. Bibcode:1981Natur.293...55H. doi:10.1038/293055a0. PMID 7266658. S2CID 22902112.

- Wilder, Jason; Mobasher, Zahra; Hammer, Michael (2004). "Genetic evidence for unequal effective population sizes of human females and males". Mol Biol Evol. 21 (11): 2047–57. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh214. PMID 15317874.

- Fletcher, Garth; Simpson, Jeffry; Campbell, Lorne; Overall, Nickola (1 January 2015). "Pair-Bonding, Romantic Love, and Evolution: The Curious Case of "Homo sapiens"". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 10 (1): 20–36. doi:10.1177/1745691614561683. JSTOR 44281912. PMID 25910380. S2CID 16530399. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- Tennov, Dorothy (1999). Love and Limerence: the Experience of Being in Love. Scarborough House. ISBN 978-0-8128-6286-7. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Leggett, John C.; Malm, Suzanne (March 1995). The Eighteen Stages of Love: Its Natural History, Fragrance, Celebration and Chase. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-882289-33-2. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Musharoff, Shaila; Shringarpure, Suyash; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Ramachandran, Sohini (20 September 2019). "The inference of sex-biased human demography from whole-genome data". PLOS Genetics. Public Library of Science (PLoS). 15 (9): e1008293. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008293. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 6774570. PMID 31539367.

- Booth, Hannah (1 April 2017). "The kingdom of women: the society where a man is never the boss". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- Keinan A, Reich D (2010). "Can a sex-biased human demography account for the reduced effective population size of chromosome X in non-Africans?". Mol Biol Evol. 27 (10): 2312–21. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq117. PMC 2944028. PMID 20453016.

- "Accesstoinsight.org". Accesstoinsight.org. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- The Ethics of Buddhism, Shundō Tachibana, Routledge, 1992, ISBN 978-0-7007-0230-5

- An introduction to Buddhist ethics: foundations, values, and issues, Brian Peter Harvey, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-521-55640-8

- Berzin, Alexander (7 October 2010). "Buddhist Sexual Ethics: Main Issues". Study Buddhism. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Markale, Jean (1986) [1st pub. 1972 La Femme Celte (in French)]. "The Judicial Framework". Women of the Celts. Translated by Mygind, A.; Hauch, C.; Henry, P. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-89281-150-2. LCCN 86-20128. OCLC 14069840. OL 2726337M.

- Fries, Jan (2003). Cauldron of the Gods: A manual of Celtic magick. Oxford: Mandrake. p. 192. ISBN 9781869928612.

- McLeod, Neil (2005). "Brehon law". In Duffy, Seán (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 42–45. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- State, Paul F. (2009). A brief history of Ireland. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0816075171.

- Fox, Martin and O'Ciarrai, Breandan. "Céard is Sinnsreachd Ann? (What Is Sinnsreachd?) Archived 31 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine", Tuath na Ciarraide, 7 March 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Nyami, Faith (11 February 2018). "Cleric: Christian men can marry more than one wife". Daily Nation. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Mamdani, Zehra (28 February 2008). "Idaho Evangelical Christian polygamists use Internet to meet potential spouses". Deseret News. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Genesis 2:24, Matthew 19:3–6

- 1 Corinthians 6:16

- Wilber, David (26 August 2021). "Monogamy: God's Creational Marriage Ideal".

- Genesis 2:24

- Matthew 19:3–9

- 1 Timothy 3:2

- The Digital Nestle-Aland lists only one manuscript (P46) as source of the verse, while nine other manuscripts have no such verse, cf. http://nttranscripts.uni-muenster.de/AnaServer?NTtranscripts+0+start.anv

- Letter to Philip of Hesse, 10 December 1539, De Wette-Seidemann, 6:238–244

- Michelet, ed. (1904). "Chapter III: 1536–1545". The Life of Luther Written by Himself. Bohn's Standard Library. Translated by Hazlitt, William. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 251.

- James Bowling Mozley Essays, Historical and Theological 1:403–404 Excerpts from Der Beichtrat

- Letter to the Chancellor Gregor Brück, 13 January 1524, De Wette 2:459.

- "Law of the Land – Exegesis – Biblical Polygamy . com". biblicalpolygamy.com.

- Ugwu, Kelvin (28 April 2022). "Understanding The Scriptural Teaching on Polygamy". Pen Shuttle. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- On Marriage and Concupiscence, I,10

- Marcus, Joel (April 2006). "Idolatry in the New Testament". Interpretation. 60 (2): 152–164. doi:10.1177/002096430606000203. S2CID 170288252.

- Augustine, On the Good of Marriage, ch. 20; cf. On Marriage and Concupiscence, I,10

- St. Augustin On the Good of Marriage, ch.17; cf. On Marriage and Concupiscence, I,9.8

- On the Good of Marriage, ch.1

- On the Good of Marriage, ch.3