Popular Will

Popular Will (Spanish: Voluntad Popular, abbr. VP) is a political party in Venezuela founded by former Mayor of Chacao, Leopoldo López, who is its national co-ordinator. The party previously held 14 out of 167 seats in the Venezuelan National Assembly, the country's parliament, and is a member of the Democratic Unity Roundtable, the electoral coalition that held a plurality in the National Assembly between 2015 and 2020. The party describes itself as progressive and social-democratic,[2][3][4] and was admitted into the Socialist International in December 2014.[5] Observers have also described it as being centrist,[4][6][7][8] or centre-left.[9][10]

Popular Will Voluntad Popular | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | VP |

| Leader | Leopoldo López (elected)[1] |

| Founded | 5 December 2009 |

| Split from | Primero Justicia |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre to centre-left |

| National affiliation | Unitary Platform |

| International affiliation | Socialist International |

| Colours | Orange |

| Seats in the National Assembly | 0 / 277

|

| Seats in the Latin American Parliament | 2 / 12

|

| Seats in the Mercosur Parliament | 3 / 23

|

| Governors | 0 / 23

|

| Mayors | 15 / 337

|

| Website | |

| www | |

The party was formed in reaction to complaints of infringements of individual freedom and human rights on the part of the government of the Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro. The party attempts to bring together Venezuelans of various backgrounds who consider Chavismo oppressive and authoritarian. Popular Will self-identifies itself as "a pluralist and democratic movement" that is committed to "progress", which it defines as the realization of "the social, economic, political, and human rights of every Venezuelan."[11] The party says its "fundamental pillars" are progress, democracy, and social action.[11]

History

Background and foundation

Popular Will traces its roots to the Popular Networks (Redes Populares) formed in 2004 as a means of promoting social action and leadership. The year 2007 saw the formation of the so-called "2D" opposition movement, which considered the constitutional referendum called by Hugo Chávez an attempt to impose dictatorship on the country.

This was followed in 2009 by the formation of the Social Action (Accion Social) movement, which brought together "youths, workers, community leaders, business people, and politicians."[11]

On 5 December 2009, López, along with the other leaders of other political parties, Un Nuevo Tiempo, Primero Justicia, and Acción Democrática,[12][13] officially announced the formation of the Popular Will Movement (Movimiento Voluntad Popular) at a forum in Valencia, Carabobo.

The National Electoral Council, on 1 February 2010, refused to allow the group to call itself Movimiento Voluntad Popular, supposedly because of the similarity between this name and that of the Movimiento Base Popular, a regional political party in Apure. This frustrated the party's desire to field candidates in the 2010 parliamentary election; nonetheless, three party members won election to the National Assembly, two of them with the support of the Coalition for Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD).[14]

On 14 January 2011, the National Electoral Council of Venezuela (Consejo Nacional Electoral) formally accepted Popular Will as a legitimate political party. This was followed by an unprecedented event in Venezuelan political history, namely the choice of a party's officials in open elections, which were held on 10 July 2011. Later, MUD candidates for the presidency and state government offices were selected in primaries that took place on 12 February 2012. Leopoldo López had retired himself and supported Henrique Capriles Radonski who was elected as the MUD candidate for presidential election of 7 October 2012. Hugo Chávez was reelected as president and the party received 471,677 votes. In the regional elections on 16 December 2012, the party was established as the fourth largest party in MUD coalition and as the sixth nationwide. The youth leader, David Smolansky, won the 2013 municipal election for mayor of the municipality of El Hatillo in Miranda State.[15]

The party is a member of the Democratic Unity Roundtable, the electoral coalition that held a plurality in the Venezuelan National Assembly, and between 2015 and 2020 it held 14 out of 167 seats in the National Assembly until losing all of its seats in the 2020 parliamentary elections, when the party did not participate in the elections due to considering the vote to not be sufficiently fair and free.[16]

Protest movement

.jpg.webp)

The Popular Will Party played a central role in the protests that took place in Venezuela in early 2014. López was blamed by the government of president Nicolas Maduro for three deaths that occurred during protests on 12 February, and the next day a Caracas court upheld a request from the Public Prosecutor's Office to order his arrest. "Without a doubt, the violence was created by small groups coordinated, exalted and financed by Leopoldo López," said Jorge Rodriguez, the Socialist Party mayor of the Libertador municipality in Caracas.

"The government is playing the violence card, and not for the first time," López claimed. "They're blaming me without any proof....I have a clear conscience because we called for peace." He added: "We won't retreat and we can't retreat because this is about our future, about our children, about millions of people."[17] On 16 February, López announced he would turn himself in to the Venezuelan government after one more protest. "I haven't committed any crime," he said. "If there is a decision to legally throw me in jail I'll submit myself to this persecution."[18]

In early March 2014, a peaceful protest march in Caracas, organized by the Student Movement (Movimiento Estudiantil) and supported by Popular Will, was dispersed by members of the National Guard (GNB) and National Police (PNB) using tear gas and gunshots. This action prevented the marchers from reaching the headquarters of the national Ombudsman, where they planned to demand the resignation of Gabriela Ramirez for justifying acts of torture and other violations of human rights committed by the government of Nicolás Maduro. At this point López had been in prison for 22 days.[19] Popular Will, in response to this action, stated that Maduro, "in addition to being illegitimate, is a murderer." Party official Freddy Guevara emphasized that Popular Will believed in a peaceful and constitutional transfer of power, and called on the Venezuelan people to maintain pressure on the government to provide justice and freedom, saying that "the power of the street" must be used "to force the government to uphold the constitution." He added. "We cannot rest until Leopoldo López is free."[20]

Arrests

Since the party became more involved in Venezuela's protest movement, numerous members of Popular Will have been arrested. In March 2018, The New York Times reported that over 90 members of Popular Will have been detained by the Maduro government.[21]

Party headquarters raid

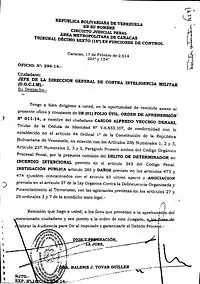

On 17 February 2014, "alleged members of military counterintelligence" broke into the headquarters of Popular Will without a search warrant and holding people at gunpoint. In videotapes of the incident that were later made public, armed men are seen threatening people in one room of the headquarters and violently breaking down a door in order to enter another room. Carlos Vecchio, the party's national political coordinator, reported the incident via Twitter. López, in his own tweet, urged his followers to spread the word about the incident.[22]

Arrest of López

.jpg.webp)

On 18 February 2014, López delivered a speech in Plaza Brión calling for "a pacific exit" from authoritarian government, "within the constitution but in the streets." He lamented the loss of independent media in the country and declared that if his imprisonment helped Venezuelans to wake up once and for all and demand change, it would have been worth it. He said he could have left the country, but instead had "stayed to fight for the oppressed people in Venezuela."[23] He thereupon turned himself in to the National Guard, saying that he was handing himself over to a "corrupt justice" system.[24] On 20 February, Supervisory Judge Ralenis Tovar Guillén, issued a pre-trial detention order against López in response to formal charges of "arson of a public building," "damages to public property," "instigation to commit a crime," and "associating for organized crime."[25]

Human-rights organizations around the world condemned the arrest of López, with Amnesty International, in a 19 February statement, calling it "a politically motivated attempt to silence dissent"[26] and Human Rights Watch accusing the Venezuelan government of adopting "the classic tactics of an authoritarian regime."[27] The New York-based Human Rights Foundation declared López a prisoner of conscience on 20 February and called for his immediate release, adding: "Either Maduro releases López and calls for an honest dialogue with all of the opposition, or he must step down for the sake of all Venezuelans: both those who support Chavismo and those who do not. Venezuela does not need an executioner willing to kill half of the country. Venezuela needs a president."[25]

On 26 February, López's wife, Lilian Tintori, led a quiet protest of female students just prior to a government peace conference.[28]

Arrest warrant for Vecchio

The day after López's arrest, the government issued an arrest warrant for Carlos Vecchio, who with López in jail was serving as the de facto leader of Popular Will. He was charged with the same offenses as López: arson, criminal association, damages to public property, and instigation to commit a crime.[29] Vecchio, who was in hiding, defied the arrest order. Meanwhile, public unrest continued, with the official death toll from more than two weeks of violence rising to 17.[30] Enrique Betancourt, writing in the Yale Daily News, described Vecchio, a 2013 Yale World Fellow, as a champion of freedom who, unlike López, "is not an internationally recognizable figure (yet)." Betancourt expressed the concern that this "relative anonymity will allow government forces to arrest Carlos and violate his human rights with impunity and without fear of any international repercussion."[31] On 22 March, as street protests continued, Vecchio, still defying the arrest order, addressed a crowd of supporters in Caracas.[32]

Ideology

Popular Will has been variously described as right wing, even "fascist" by the government, but calls itself a centre[6][4][8] to centre-left[9] party, with socialist and progressive tendencies, although some sources have also described it as centre-right.[33] The party supports LGBT rights, and following the 2015 parliamentary election, the first two LGBT members of the Venezuelan legislature (Tamara Adrián and Rosmit Mantilla) were elected under Popular Will's banner.[34][35]

Party platform

The party platform, "The Best Venezuela" (La Mejor Venezuela), calls for an open, transparent government and for the punishment of abuses of power by public officials. It supports globalization and calls for an inclusive society "without regard to wealth, religion, age, race, sexual orientation, gender identity, or political opinions."[36] López, when running for president, called for greater autonomy in fiscal matters to be given to governors and mayors.[37]

The party seeks to make Venezuela the world's largest producer and exporter of oil. López does not seek to nationalize oil firms but says that oil income should be used to form a "Solidarity Fund" to help alleviate extreme poverty and finance an efficient system of social security, as well as to diversify the non-oil sectors of the nation's economy. López also opposes price controls and favors subsidizing domestic production.[38] He supports the market economy and opposes "state capitalism."[39]

The party's "real battle," López has claimed, is "against poverty, exclusion, and disrespect for human rights."[40] In opinion pieces in December 2013 and January 2014, he proposed the creation of a "Social Forum" within the context of which Venezuelans could "discuss and rethink" the country's future and forge a "new social pact." López expressed the view "that mineral resources are owned by the nation" and that "democratizing oil" can lead to a democratization of income. He also encouraged Venezuelans to invest in the oil business in order to "participate in its production."[41] In the January article, López described Popular Will as a grassroots "social and political" movement that "avoids the harmful practices of old and new political parties" and that is opposed to "warlordism and cronyism in the selection of its authorities." He added that Popular Will does "not share the vision of a hegemonic state that controls everything and decides everything"; rather, government's role is to promote the development of human capabilities, to help people flourish as free citizens, to cultivate "social solidarity," and to foster "respect for the constitution."[42]

In order to forge "the best Venezuela," López has written, Venezuelans must focus on "peace, welfare, and progress," and must engage in "a broad process of consultation and reflection…with groups of experts in specific subject areas and with social movements, as well as with communities, in dialogues in which we can feel the needs and cries of Venezuelans." He has expressed confidence that Venezuelans "can construct a country in which the problems that have never been solved can be solved, the eternal problems that exist from generation to generation." López has further spoken of creating a Venezuela "where liberty is exercised in a constructive and responsible manner,...and where opportunities are created for all Venezuelans, regardless of wealth, religion, age, race, sexual orientation, gender identity, or political persuasion."[36]

López has said that Venezuela must commit itself to strengthening production and bringing down inflation, which, he said, would reduce corruption and enable Venezuelans to save money. He has held up the examples of Brazil, Peru, Argentina, and Colombia as countries "that had hyperinflation and achieved price stability." He criticized price controls, saying that Venezuela, while having "a number of controls," also had "the continent's highest inflation."[39]

López has described his foreign policy as "win-win" policy, the objective of which would be to solve the country's problems and to promote peace, welfare, and progress. He has said that he would curb the "ideologized" foreign policy of the current government. López has also expressed belief in a multipolar world in which Venezuela would play a role as an international champion of democracy and human rights.[37]

View of Bolivarian government

The party's manifesto states: "This is an infamous epoch because the laws are used to create injustice; it is a disastrous epoch because the laws are used to subdue, frighten and eliminate the people who protest and who demand justice".[11]

In January 2012, López, at the time a presidential candidate, described the current Venezuelan government as authoritarian, and called on Venezuelans to join him in choosing "the path of democracy." He said that the "first commitment" of government must be to justice, specifically to "functioning courts," an end to impunity, and an end to corrupt tax authorities.[37]

International views

While living in exile, during a press conference in the Círculo de Bellas Artes, in Madrid, in October 2020 Leopoldo López expressed that his goal now was to have "free and transparent" elections in Venezuela, saying that "we want for Venezuela the same as in Bolivia", referring to the 2020 Bolivian elections, where the Movement for Socialism (MAS) candidate Luis Arce was elected president.[43] In exile, López has also declared that "for a transition to be viable" support from the "Maduro regime" was needed,[44] citing as examples South Africa, Eastern Europe and Spain,[44][45] but saying that those who have committed human rights abuses or crimes against humanity should not be included.[44]

On 9 December, Leopoldo López started a tour in Latin America, travelling to Colombia and seeking to "streghten" an "international front" against Nicolás Maduro, after the Venezuelan parliamentary election that year, which he considered fradulent.[46][47] On 23 López met with the president of the National Assembly of Ecuador, Guadalupe Llori, who on 24 May would be in charge of inaugurating president elect Guillermo Lasso, stressing female leadership "in a moment where in Latin America is badly needed".[48] He travelled later to Peru, during the Peruvian general election, and on 29 May participated in a political panel with politicians and businesspeople related to the right-wing presidential candidate Keiko Fujimori, daughter of the imprisoned former president of Peru Alberto Fujimori, saying that Fujimori represented "freedom" and "democracy" while he characterized her opponent Pedro Castillo as supporting "dictatorship" and "communism". López criticized Castillo for openly declaring that Venezuela was a full democracy.[49] On 23 June, after travelling to the United States and meeting with Republican congressman Rick Scott, López declared that the United States would not lift sanctions "without significant advances".[50]

Mayors

- Fabio José Canache – Píritu, Anzoátegui

- Lumay Barreto – Páez, Apure

- Delson Guarate – Mario Briceño Iragorry, Aragua

- José Gregorio "Gollo" Martínez – Piar, Bolívar

- Yovanny Salazar – Chaguaramas, Guárico

- Álvaro Sánchez – Rangel, Mérida

- David Smolansky – El Hatillo, Miranda

- Warner Jiménez – Maturín, Monagas

- Luis Daniel "Sañelo" Cabeza – Bolívar, Sucre

- Patricia de Ceballos – San Cristóbal, Táchira

- Alberto Maldonado – Torbes, Táchira

- Alejandro "Tato" García – Ureña, Táchira

- William Galavis – Guásimos, Táchira

- José Karkom – Valera, Trujillo

- José Acisclo Viloria – Miranda, Trujillo

References

- "América Latina Supremo de Venezuela solicitó formalmente a España la extradición de Leopoldo López" (in Spanish). Deutsche Welle. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Recognizing Juan Guaidó as Venezuela's Leader Isn't a Coup. It's an Embrace of Democracy". Foreign Policy.

- "CP #12: La Socialdemocracia y el Progresismo en Voluntad Popular". ideas.voluntadpopular.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Future Not Bright For Socialists United Of Venezuela". Forbes. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

Guaido, 35, is president of the National Assembly. His equivalent in the U.S. would be Nancy Pelosi. He is a member of the Popular Will party, a centrist, social-democratic party, which means talk of a right-wing coup looking to topple Maduro is a bit far-fetched.

- "Socialist International - Progressive Politics For A Fairer World". www.socialistinternational.org.

- Romero, Simon; Díaz, María Eugenia (21 October 2011), "A Bolívar Ready to Fight Against the Bolivarian State", The New York Times

- "Venezuela: A simple guide to understanding the current crisis". Al Jazeera. 2 February 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

He was a founding member of a centrist political party, Popular Will, working directly with key opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez.

- Gavin O'Toole, ed. (2017). Politics Latin America. Routledge. ISBN 9781351996402.

... As a result, in 2015 Leopoldo López, leader of the Voluntad Popular (VP, Popular Will) party, was jailed. Although VP is a centrist party, ...

- Dudley Edwards, Ruth (14 December 2014). "What's good for Venezuelan goose isn't good for Irish gander". ruthdudleyedwards.co.uk. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Leopoldo López taunts Maduro after court orders arrest". Buenos Aires Times. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

Popular Will describes itself as a progressive centre-left movement.

- "Quienes Somo?". Voluntad Popular. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Manifiesto de Voluntad Popular (Spanish, visited 21 September 2010)

- Dirigentes opositores lanzan movimiento Voluntad Popular en Carabobo Archived 15 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish, visited 5 December 2009)

- Negado en el CNE conformación del Movimiento Voluntad Popular dirigido por Leopoldo López (Spanish, visited 11 February 2010)

- Leopoldo López anunció que Voluntad Popular es ahora un partido político Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish, visited 18 January 2011)

- "AP Explains: Options narrowing for Venezuela's opposition". Washington Post. Associated Press. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Cawthorne, Andrew (13 February 2014). "Venezuela seeks protest leader's arrest after unrest kills three". Reuters.

- Gupta, Girish. "Venezuelan opposition leader says he'll turn himself in". USA Today.

- "Voluntad Popular llama a no retroceder en la protesta pacífica". El Universal. 12 March 2014.

- "Voluntad Popular pide que lucha en la calle exija renovación de poderes". Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Hylton, Wil S. (9 March 2018). "Leopoldo López Speaks Out, and Venezuela's Government Cracks Down". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Difunden imágenes de allanamiento ilegal en sede del partido Voluntad Popular, de Leopoldo López". La Republica. 17 February 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Leopoldo López se entrega a funcionarios de la GN - Nacional y Política". www.eluniversal.com. 13 October 2022.

- ""Si mi encarcelamiento es el despertar de un pueblo, valdrá la pena"". Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Venezuela HRF declares Leopoldo Lopez a Prisoner of Conscience and calls for his immediate release". Human Rights Foundation.

- "Venezuela: Trial of opposition leader an affront to justice and free assembly". Amnesty USA.

- "Venezuela: Violence Against Protesters, Journalists". 21 February 2014.

- Wilson, Peter (26 February 2014). "Women in white protest violence in Venezuela". USA Today.

- "María Corina Machado denuncia que dictaron orden de captura en su contra #24Abr".

- Mogollan, Mary, & Chris Kraul (28 February 2014). "Venezuela seeks opposition figure's arrest; protest death toll rises". LA Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "BETANCOURT: Don't forget Vecchio". Yale Daily News. 24 February 2014.

- "Supporters hold out their hands to greet Carlos Vecchio, the national political coordinator of the Popular Will party, an anti-government group formed by jailed opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez before his arrest, during an anti-government protest in Caracas, Venezuela, Saturday, March 22, 2014. Vecchio addressed the crowd in defiance of an arrest order. Two more people were reported dead in Venezuela as a result of anti-government protests even as supporters and opponents of President Nicolas Maduro took to the streets on Saturday in new shows of force. (AP Photo/Fernando Llano) | View photo - Yahoo News". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "Rights Trampled in Venezuelan Protests". Inter Press Service. 27 February 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Yajure, Jesús Alberto (7 December 2015). "Tamara Adrián: "Mi candidatura es una punta de lanza para el avance de los derechos de LGBT"". Runrun.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Elected congressmen fight to get out of jail in Venezuela". Fusion, 14 December 2015.

- "Una mejor propuesta, para Una Mejor Venezuela | Leopoldo Lopez". Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Leopoldo López: nuestra política exterior será impulsar la exportación "made in Venezuela"". Noticias 24. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Leopoldo López rechaza el control de precios y apuesta por apoyar la producción nacional en Noticias24.com". www.noticias24.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Rodriguez, Mariana Martinez (23 November 2011). "Entrevista: Leopoldo López: "Levantaremos el control de cambio lo más rápido posible"". El Mundo. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- VPA, Prensa. "Carta a los socialdemócratas (II)". www.voluntadpopular.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Gomez, Elvia (18 January 2014). "López ratifica invitación a crear Foro Socialdemócrata". El Universal.

- "Leopoldo López: Bienvenido el debate". www.lapatilla.com. 17 January 2014.

- "Leopoldo López: "Queremos para Venezuela lo mismo que en Bolivia: elecciones libres"". ABC. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ""Para que la transición sea viable hay que contar con parte del régimen de Maduro"". El Independiente (in Spanish). 24 November 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Leopoldo López, en busca de una transición a la española". El Independiente (in Spanish). 31 October 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Leopoldo López viaja a Colombia en una gira que busca "afianzar" el "frente internacional" contra Maduro". Europa Press. 9 December 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Leopoldo López viaja a Colombia: esta es su agenda". CNN (in Spanish). 9 December 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Leopoldo López se reunió con la presidenta de la AN de Ecuador". El Nacional (in Spanish). 23 May 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Briceño, Franklin; Muñoz, Mauricio (30 May 2021). "Leopoldo López: Keiko Fujimori defenderá democracia en Perú". Associated Press (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 June 2021 – via Los Angeles Times.

- "Leopoldo López: EE.UU. no levantará sanciones "sin avances significativos"". ALnavío (in Spanish). 23 June 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

External links

- Official website (in Spanish)