Populous (video game)

Populous is a video game developed by Bullfrog Productions and published by Electronic Arts, released originally for the Amiga in 1989, and is regarded by many as the first god game.[2][3][4][5] With over four million copies sold, Populous is one of the best-selling PC games of all time.

| Populous | |

|---|---|

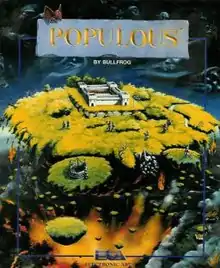

European cover art by David John Rowe[1] | |

| Developer(s) |

|

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Designer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) |

|

| Series | Populous |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | 5 June 1989 |

| Genre(s) | God game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

The player assumes the role of a deity, who must lead followers through direction, manipulation, and divine intervention, with the goal of eliminating the followers led by the opposite deity. Played from an isometric perspective, the game consists of more than 500 levels, with each level being a piece of land which contains the player's followers and the enemy's followers. The player is tasked with defeating the enemy followers and increasing their own followers' population using a series of divine powers before moving on to the next level. The game was designed by Peter Molyneux, and Bullfrog developed a gameplay prototype via a board game they invented using Lego.[6]

The game received critical acclaim upon release, with critics praising the game's graphics, design, sounds and replay value. It was nominated for multiple year-end accolades, including Game of the Year from several gaming publications. Retrospectively, it has been considered one of the greatest video games of all time. The game was ported to many other computer systems and was later supported with multiple expansion packs. It is the first game in the Populous series, preceding Populous II: Trials of the Olympian Gods and Populous: The Beginning.

Gameplay

The main action window in Populous is viewed from an isometric perspective, and it is set in a "tabletop" on which are set the command icons, the world map (depicted as an open book) and a slider bar that measures the level of the player's divine power or "mana".

The game consists of 500 levels, and each level represents an area of land on which live the player's followers and the enemy followers. In order to progress to the next level the player must increase the number of their followers such that they can wipe out the enemy followers. This is done by using a series of divine powers. There are a number of different landscapes the world (depicted on the page in the book) can be, such as desert, rock and lava, snow and ice, etc. and the type of landscape is not merely aesthetic: it affects the development of the player's and enemy's followers.

The most basic power is raising and lowering land. This is primarily done in order to provide flat land for the player's followers to build on (though it is also possible to remove land from around the enemy's followers). As the player's followers build more houses they create more followers, and this increases the player's mana level.

Increasing the mana level unlocks additional divine powers that allow the player to interact further with the landscape and the population. The powers include the ability to cause earthquakes and floods, create swamps and volcanoes, and turn ordinary followers into more powerful knights.[7]

Plot

In this game the player adopts the role of a deity and assumes the responsibility of shepherding people by direction, manipulation, and divine intervention. The player has the ability to shape the landscape and grow their civilization – and their divine power – with the overall aim of having their followers conquer an enemy force, which is led by an opposing deity.[7]

Development

Peter Molyneux led development, inspired by Bullfrog's artist Glenn Corpes having drawn isometric blocks after playing David Braben's Virus.[8][9] The game's budget was £20,000.[10]

Initially Molyneux developed an isometric landscape, then populated it with little people that he called "peeps", but there was no game; all that happened was that the peeps wandered around the landscape until they reached a barrier such as water. He developed the raise/lower terrain gameplay mechanic simply as a way of helping the peeps to move around. Then, as a way of reducing the number of peeps on the screen, he decided that if a peep encountered a piece of blank, flat land, it would build a house, and that a larger area of land would enable a peep to build a larger house. Thus the core mechanics – god-like intervention and the desire for peeps to expand – were created.[8][9]

The endgame – of creating a final battle to force the two sides to enter a final conflict – developed as a result of the developmental games going on for hours and having no firm end.[8][9]

Bullfrog attempted to prototype the gameplay via a board game they invented using Lego, and Molyneux admits that whilst it didn't help the developers to balance the game at all, it provided a useful media angle to help publicise the game.[8][11] One curious incident related in media coverage involved an attempt by Molyneux to investigate the displacement of water when adding blocks to the world model, this being frustrated by Lego not being watertight and thus causing a "flood" that "dissuaded further experimentation".[12]

During the test phase the testers requested a cheat code to skip to the end of the game, as there was insufficient time to play through all 500 levels, and it was only at this point that Bullfrog realised that they had not included any kind of ending to the game. The team quickly repurposed an interstitial page from between levels and used it as the final screen.[8]

After demoing the game to over a dozen publishers, Bullfrog eventually gained the interest of Electronic Arts, who had a gap in their spring release schedule and was willing to take a chance on the game. Bullfrog accepted their offer, although Molyneux later described the contract as "pretty atrocious:" 10% royalties on units sold, rising to 12% after one million units sold, with only a small up-front payment.[8]

Peter Molyneux presented a post-mortem of the game's development and work in progress on a related personal project at Game Developers Conference in 2011.[13]

Expansion packs

Bullfrog produced Populous World Editor, which gave users the ability to modify the appearance of characters, cities, and terrain.[14] An expansion pack called Populous: The Promised Lands added five new types of landscape (the geometric Silly Land, Wild West, Lego style Block Land, Revolution Française, and computer themed Bit Plains). In addition, another expansion disk called Populous: The Final Frontier added a single new landscape-type and was released as a cover disk for The One.[15]

Reception

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Computer and Video Games | 96% (Amiga)[16] |

| Dragon | |

| Famitsu | 31/40 (SNES)[18] |

| Raze | 89% (Mega Drive)[19] |

| Zero | 92% (Amiga)[20] |

| Computer Gaming World | |

| Console XS | 88% (Master System)[22] |

| Games International | |

| MegaTech | 91% (Mega Drive)[24] |

| Your Amiga | 93% (Amiga)[25] |

| ST/Amiga Format | 92% (Amiga)[26] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Computer Gaming World | Strategy Game of the Year (1990)[27] |

| Origins Award | Best Military or Strategy Computer Game of 1990[28] |

| Video Games & Computer Entertainment | 1990 Computer Game of the Year |

Populous was released in 1989 to almost universal critical acclaim. The game received a 5 out of 5 stars in 1989 in Dragon #150 by Hartley, Patricia, and Kirk Lesser in "The Role of Computers" column.[17] Biff Kritzen of Computer Gaming World gave the game a positive review, noting, "as heavy-handed as the premise sounds, it really is a rather light-hearted game." The simple design and layout were praised, as were the game's colourful graphics.[11] In a 1993 survey of pre 20th-century strategy games the magazine gave the game three stars out of five, calling it a "quasi-arcade game, but with sustained play value".[21] MegaTech magazine stated that the game has "super graphics and 500 levels. Populous is both highly original and amazingly addictive, with a constant challenge on offer". They gave the Mega Drive version of Populous an overall score of 91%.[24]

In the September–October 1989 edition of Games International (Issue #9), John Harrington differed from other reviewers, only giving the game a rating of 2 out of 5, calling it "repetitive" and saying, "Although you take on the role of a god, somehow there is a lack of mystique about this game, and despite the cute graphics, the colourful worlds and the commendably elegant icon-driven game system, this game left me with a less than 'god like' feeling."[23]

Computer and Video Games reviewed the Amiga version, giving it an overall score of 96%.[16] Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu gave the SNES version 31 out of 40.[18] Raze gave the Mega Drive version of Populous an overall score of 89%.[19] Zero gave the Amiga version of Populous an overall score of 92%.[20] Your Amiga gave the Amiga version of Populous an overall score of 93%.[25] ST/Amiga Format gave the Amiga version of Populous an overall score of 92%.[26]

Maxwell Eden reviewed Populous World Editor for Computer Gaming World, and stated that "Now all Populous fans wanting to be apprentice wizards can share in the magic of that gift. Populous is a great game and PWE is an ideal enhancement that breathes new life into weary bytes. Absolute power was never as incorruptible, nor this creative."[14]

Compute! named the game to its list of "nine great games for 1989", stating that with "great graphics, a simple-to-learn interface, and almost unlimited variety, Populous is a must buy for 1989".[29] Peter Molyneux estimated that the game accounted for nearly a third of all the revenue of Electronic Arts in that year.[8]

Orson Scott Card in Compute! criticized the game's user interface, but praised the graphics and the ability to "create your own worlds ... you control the world of the game, instead of the other way around".[30] STart in 1990 gave "kudos especially to Peter Molyneux, the creative force behind Populous". The magazine called the Atari ST version "a fascinating, fun and challenging game. It's unlike any other computer game I've ever seen, ever. Don't miss it, unless you are a dyed-in-the-wool arcade gamer who has no time for strategy".[31] Entertainment Weekly picked the game as the No. 16 greatest game available in 1991, saying: "Talk about big-time role-playing. Most video games posit you as a mere sword-wielding, perilously mortal human; in Populous you're a deity. Slow-paced, intricate, and difficult to learn: You literally have to create entire worlds while all the time battling those pesky forces of evil."[32]

The game was released in the same month that The Satanic Verses controversy gained publicity in the United States following the publication of The Satanic Verses in the United States. Shortly after release, Bullfrog was contacted by the Daily Mail and was warned that the "good vs evil" nature of the game could lead to them receiving similar fatwā, although this did not materialize.[8]

By October 1997, global sales of Populous had surpassed 3 million units, a commercial performance that PC Gamer US described as "an enormous hit".[33] By 2001, Populous had sold four million copies,[34][35] making it one of the best-selling PC games of all time.

Awards

In 1990 Computer Gaming World named Populous as Strategy Game of the Year.[27] In 1996, the magazine named it the 30th best game ever, with the editors calling it "the father of real-time strategy games".[36] In 1991 it won the Origins Award for Best Military or Strategy Computer Game of 1990,[28] the 1990 Computer Game of the Year in issue 25 of American video game magazine Video Games & Computer Entertainment, and was voted the sixth best game of all time in Amiga Power.[37] In 1992 Mega placed the game at No. 25 in their Top Mega Drive Games of All Time.[38] In 1994, PC Gamer US named Populous as the third best computer game ever. The editors hailed it as "unbelievably addictive fun, and one of the most appealing and playable strategy games of all time."[39]

In 1999, Next Generation listed Populous as number 44 on their "Top 50 Games of All Time", commenting that, "A perfect blend of realtime strategy, resource management, and more than a little humor, it remains unsurpassed in the genre it created."[40] In 2018, Complex placed the game 98th on their "The Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time".[41] IGN ranked Populous 70th on its "Top 100 SNES Games of All Time."[42]

Legacy

In 1990 Bullfrog used the Populous engine to develop Powermonger, a strategic combat-oriented game with similar mechanics to Populous, but with a 3-dimensional graphical interface. In 1991 they developed and released a true sequel, Populous II: Trials of the Olympian Gods, and in 1998 a further direct sequel, Populous: The Beginning.

Populous was also released on the SNES, developed by Imagineer as one of the original titles for the console in Japan,[9] and features the addition of a race based on the Three Little Pigs.

Populous DS, a new version of the game (published by Xseed Games in America and Rising Star Games in Europe), was developed by Genki for the Nintendo DS and released 11 November 2008. The game allows the user to shape the in-game landscape using the DS's stylus. It also features a multiplayer mode allowing four players to play over a wireless connection.[43]

Populous has been re-released through GOG.com and on Origin through the Humble Origin Bundle sale. It runs under DOSBox.

The browser-based game Reprisal was created in 2012 by Electrolyte and Last17 as a homage to Populous.[44][45]

Godus (formerly Project GODUS) was revealed as a URL on the face of Curiosity – What's Inside the Cube?, and "is aimed to reimagine" Populous.[46]

References

- "David John Rowe's artist page". Box Equals Art. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- Edge Staff (1 November 2007). "50 greatest game design innovations". Edge. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "IGN Hall of Fame: Populous". IGN. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Ernest Adams (2008). "What's Next for God Games". Designer's Notebook. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- "75 Power Players". Next Generation. No. 11. November 1995. p. 51. ISSN 1078-9693.

Its first title, Populous, created a whole new genre, the 'God' game.

- Candy, Robin (September 1989). "Bullfrog: Ribbeting Stuff". The Games Machine. No. 22. pp. 75–76. ISSN 0954-8092.

- Bullfrog (1989). "Populous Amiga version user manual" (PDF). Populous. Electronic Arts.

- Molyneux, Peter (2011). "Game Developer's Conference - Classic Game Post-Mortem: Populous". GDC Vault. UBM Tech. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Edge Staff (2012). "The Making Of: Populous". Edge. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Foster, Michael (5 March 1995). "Britain faces game drain". The Observer. p. 38. Retrieved 6 April 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kritzen, Biff (August 1989). "And On The Eighth Day..." Computer Gaming World. No. 62. pp. 16–17. ISSN 0744-6667.

- Wade, Bob (March 1989). "And Frog Created Man". Advanced Computer Entertainment. No. 18. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- "Classic Game Postmortem:Populous". Gamasutra. UBM Tech. 17 January 2017.

- Eden, Maxwell (July 1992). "The World According To...Max: Electronic Arts' Populous World Editor". Computer Gaming World. No. 96. pp. 40–41. ISSN 0744-6667.

- "The One: Final Frontier Disk". The One. No. 14. emap Images. November 1989. p. 8.

- Rignall, Julian (April 1989). "Reviews: Populous". Computer and Video Games. No. 90. pp. 30–32.

- Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (October 1989). "The Role of Computers". Dragon. No. 150. p. 68. ISSN 0279-6848.

- 30 Point Plus: ポピュラス. Weekly Famicom Tsūshin. No.358. Pg.32. 27 October 1995.

- Boardman, Julian (December 1990). "Reviews: Populous". Raze. No. 2. p. 70. ISSN 0960-7706.

- Eberneezer Bloggo (January 1992). "The Price I$ Right: Populous". Zero. No. 27. p. 82.

- M. Evan Brooks (June 1993). "An Annotated Listing of Pre-20th Century Wargames". Computer Gaming World. No. 107. p. 141. ISSN 0744-6667.

- "Software A-Z: Master System". Console XS. No. 1 (June/July 1992). United Kingdom. 23 April 1992. pp. 137–47.

- Harrington, John (September–October 1989). "Computer Games". Games International. No. 9. p. 48.

- "Game Index: Populous" (PDF). MegaTech. No. 5. May 1992. p. 78.

- Hamlett, Gordon (July 1989). "Review: Populous". Your Amiga. pp. 46–47.

- Higham, Mark (April 1989). "Review: Populous". ST/Amiga Format. No. 10. pp. 72–73.

- "CGW's Game of the Year Awards". Computer Gaming World. No. 74. September 1990. p. 70. ISSN 0744-6667.

- "The 1990 Origins Awards". The Origin Awards. The Game Manufacturers Association. 1990. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Gutman, Dan (July 1989). "Nine for '89". Compute!. p. 25. ISSN 0194-357X.

- Orson Scott Card (November 1989). "Deluged by Brilliant World-Creation Games: Entertainment Gameplay". Compute!. No. 114. p. 88. ISSN 0194-357X.

- Reese, Andrew (January 1990). "Strange New Worlds to Conquer". STart. Vol. 4, no. 6. ISSN 0889-6216.

- Strauss, Bob (22 November 1991). "Video Games Guide". Entertainment Weekly.

- "EA Signs Molyneux". PC Gamer US. Vol. 4, no. 10. October 1997. p. 79.

- Frauenfelder, Mark (May 2001). "Death Match". Wired. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Livingstone, Ian. "How British video games became a billion pound industry". BBC Teach. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "150 Best (and 50 Worst) Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. No. 148. November 1996. p. 68. ISSN 0744-6667.

- Matt Bielby; Stuart Campbell; Mark Ramshaw; Bob Wade; Trenton Webb; Gary Penn; Andy Smith; Maff Evens (May 1991). "This is Amiga Power: Amiga Power's All-time Top 100 Amiga Games". Amiga Power. p. 5.

- "Mega Top 100 Carts" (PDF). Mega. No. 1. October 1992. p. 79.

- "PC Gamer Top 40: The Best Games of All Time". PC Gamer US. No. 3. August 1994. pp. 32–42.

- "The Fifty Best Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 50. February 1999. p. 74. ISSN 1078-9693.

- Knight, Rich (30 April 2018). "The Best Super Nintendo Games of All Time". Complex. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Top 100 SNES Games of All Time - IGN.com, retrieved 29 June 2022

- Hatfield, Daemon (17 July 2008). "E3 2008: Census Taken of Populous DS". IGN. Archived from the original on 22 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Maxwell, Ben (21 May 2012). "Populous reborn in your browser". Edge. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Hamilton, Kirk (22 May 2012). "This Free Game Takes Populous And Gives It A Sworcery Makeover". Kotaku. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- "Project GODUS by 22cans — Kickstarter". Kickstarter.com. Retrieved 22 August 2013.