Port Jackson shark

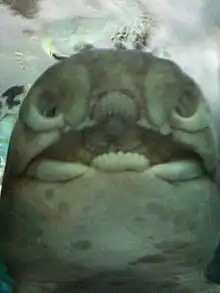

The Port Jackson shark (Heterodontus portusjacksoni) is a nocturnal,[2] oviparous (egg laying) type of bullhead shark of the family Heterodontidae, found in the coastal region of southern Australia, including the waters off Port Jackson. It has a large, blunt head with prominent forehead ridges and dark brown harness-like markings on a lighter grey-brown body,[3] and can grow up to 1.65 metres (5.5 ft) long.[4] They are the largest in the genus Heterodontus.[5]

| Port Jackson shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Heterodontiformes |

| Family: | Heterodontidae |

| Genus: | Heterodontus |

| Species: | H. portusjacksoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Heterodontus portusjacksoni (F. A. A. Meyer, 1793) | |

| |

| Range of Port Jackson shark (in blue) | |

The Port Jackson shark is a migratory species, traveling south in the summer and returning north to breed in the winter. It feeds on hard-shelled mollusks, crustaceans, sea urchins, and fish. Identification of this species is very easy due to the pattern of harness-like markings that cross the eyes, run along the back to the first dorsal fin, then cross the side of the body, in addition to the spine in front of both dorsal fins.

Distribution and habitat

The Port Jackson shark is endemic to the temperate waters around southern Australia and can be found in an area stretching from southern Queensland, south to Tasmania, and west to the central coast of Western Australia. Dubious reports exist of catchings as far north as Western Australia's York Sound. A single specimen of this species was collected in a set net at Mākara, Wellington in 1954.[6] Two more specimens reported as being from New Zealand were presented to the British Museum however although these two specimens have been located they have no information on their collection location to confirm this assertion.[6] and on one occasion, it has occurred off the coast of New Zealand. Genetic studies suggest two Australian groups, one found from Northeastern Victoria to Western Australia and the second found from Southern Queensland to New South Wales. The species is believed to have originated somewhere off the coast of South Africa.[7] It usually lives at depths of less than 100 metres (330 ft), but has been known to go as deep as 275 metres (902 ft).[8]

The shark's territory is habitually on or near the sea bottom, which is also its feeding area.[9] Rocky environments are the most common habitat, though sandy and muddy ones, as well as seagrass beds, are sometimes used.[8] During the day, when it is usually not active, it can be found in flat areas which offer some shelter from currents (including caves)[10] or near other sheltering positions such as rocky outcrops.

Movement and migration

The Port Jackson shark is a nocturnal species which peaks in activity during the late evening hours before midnight and decreases in activity before sunrise.[2] A study showed that captive and wild individuals displayed similar movement patterns and the sharks' movements were affected by time of day, sex, and sex-specific migrational behaviour.[2]

This species completes an annual migration to breed in coastal embayments with males arriving first in harbours and bays along Australia's coastline.[11] The females arrive later and stay later perhaps as a means to reduce egg predation upon their newly laid eggs. Both sexes show philopatry and high site fidelity.[11]

Port Jackson Shark movements have been quantified using tri-axial accelerometers.[12] These sensors function like Fitbits, but for sharks, and are commonly used in fish and shark species to identify important behaviours like resting, swimming and feeding.

Appearance

Port Jackson sharks can grow up to 1.65 metres (5.5 ft) long[4] and are similar to others of their genus, bearing a broad, blunt, flat head, an anal fin, and crests above its eyes. However, the species possesses characteristics that make them easily identifiable, such as their teeth and the harness-like markings which run for a majority of their body length. These markings run from their eyes to their first dorsal fin and then across the rest of their bodies. Both dorsal fins are close to equal size, each with a spine at the foremost edge. These spines are rumored to be poisonous.[8] Other features that help distinguish them are their small mouths as well as their nostrils, which are connected to their mouths.[10]

The sharks have grey-brown bodies covered by black banding, which covers a large portion of their sides and backs. One of these bands winds over the face and progresses to the shark's eyes. Another harness-shaped band goes around the back, continuing to the pectoral fins and sides. Thin, dark stripes are also present on the backs of Port Jackson sharks. These progress from the caudal fin to the first dorsal fin.[10]

Teeth

The teeth of the Port Jackson shark are one of its most distinguishable features. Unlike other sharks, its teeth are different in the front and back. The front teeth are small, sharp and pointed, while the back teeth are flat and blunt. These teeth function to hold, break then crush and grind the shells of the mollusks and echinoderms upon which this species feeds. Juveniles of the species have sharper teeth and their diet has a higher proportion of soft-bodied prey than adults.[8]

Respiratory system

The Port Jackson shark has five gills, the first supports only a single row of gill filaments, while the remaining four support double rows of filaments. Each of the second to the fifth gill arches supports a sheet of muscular and connective tissue called a septum. The shark possesses behind each eye an accessory respiratory organ called a spiracle. Along the top and bottom of each gill filament are delicate, closely packed, transverse flaps of gill tissue known as secondary lamellae. It is these lamellae that are the actual sites of gas exchange. Each lamella is equipped with tiny arteries that carry blood in a direction opposite to that of the water flowing over them. To compensate for the relatively low concentration of dissolved oxygen in seawater, water passes over the secondary lamellae of sharks some 5% as fast as air that remains in contact with the equivalent gas exchange sites, such as the alveoli of the lungs found in humans. This delay allows sufficient time for dissolved oxygen to diffuse into a shark's blood.

Port Jackson sharks have the ability to eat and breathe at the same time. This ability is unusual for sharks which mostly need to swim with their mouths open to force water over the gills. The Port Jackson shark can pump water into the first enlarged gill slit and out through the other four gill slits. By pumping water across the gills, the shark does not need to move to breathe. It can lie on the bottom for long periods of time.

Reproduction

Male Port Jackson sharks become sexually mature between ages 8 and 10, and females at 11 to 14. They are oviparous, meaning that they lay eggs rather than give live birth to their young. The species has an annual breeding cycle which begins in late August and continues until the middle of November. During this time, the female lays pairs of eggs every 8–17 days.[13] As many as eight pairs can be laid during this period. The eggs mature for 10–11 months before the hatchlings, known as neonates, can break out of the egg capsule. The eggs have been assessed in recent studies as having an 89.1% mortality rate, mostly from predation.[10]

Digestive system

Digestion of food can take a long time in the Port Jackson shark. Food moves from the mouth to the J-shaped stomach, where it is stored and initial digestion occurs. Unwanted items may never get any further than the stomach, and are coughed up again. They have the ability to turn their stomachs inside out and spit it out of their mouths to get rid of any unwanted contents. One of the biggest differences in digestion in the shark when compared to mammals is the extremely short intestine. This short length is achieved by the spiral valve with multiple turns within a single short section instead of a very long tube-like intestine. The valve provides a very long surface area for the digestion of food, requiring it to pass around inside the apparently short gut until fully digested, when remaining waste products pass by. The most obvious internal organ in sharks is the huge liver, which often fills most of the body cavity. Dietary items include sea urchins, molluscs, crustaceans, and fishes. Black sea urchins (Centrostephanus rodgersii) are often eaten. Port Jackson Sharks forage for food at night when their prey are most active. They often use caves and rocky outcrops as protection during the day.

The teeth of the Port Jackson shark are very different from other shark species. They are not serrated, and the front teeth have a very different shape from those found at the back of the jaws, hence the genus name Heterodontus (from the Greek heteros, meaning different, and dont, meaning tooth). The anterior teeth are small and pointed, whereas the posterior teeth are broad and flat. The teeth function to hold and break, then crush and grind the shells of molluscs and echinoderms. Juvenile Port Jackson sharks have more pointed teeth and feed on a higher proportion of soft-bodied prey than adults. They can feed by sucking in water and sand from the bottom, blowing the sand out of the gill slits, and retaining the food, which is swallowed.

Behaviour and learning

Port Jackson shark adults are often seen resting in caves in groups, and prefer to associate with specific sharks based on sex and size.[14] Juvenile Port Jackson sharks, on the other hand, do not appear to be social. A captive study showed that these juveniles did not prefer to spend time next to other sharks, even when they were familiar with each other (i.e. tank mates).[15] Juvenile Port Jackson sharks have unique personality traits, just like humans.[16] Some were bolder than others when exploring a novel environment and they also reacted differently to a stressful situation (in choosing a freeze or flight response).

Juvenile Port Jackson sharks are also capable of learning to associate bubbles, LED lights, or sounds with receiving a food reward,[17][18] can distinguish different quantities (i.e. count),[19] and can learn by watching what other sharks are doing.

At least in some of these lab experiments males are shyer than females and boldness increases with consecutive trials of the same experiment. In experiments with different music genres, none of the sharks tested learned to discriminate between a jazz and a classical music stimulus.[18]

Relationship with humans

The shark has no major importance to humans. It is not an endangered species and is not used as a common food supply. It is, however, useful when scientists are hoping to study bottom-dwelling sharks and can be vulnerable to being caught as bycatch. It also does not pose any danger to humans.[10] In October 2011 a man was bitten by a Port Jackson shark at Elwood Beach near Melbourne. The bite did not pierce the skin and the man was able to swim away while the shark was latched on to his calf.[20]

Conservation

Although listed as "Least Concern" on the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Red List, the shark's egg capsules experience very high mortality rates (estimated at 89.1%). Its status is otherwise largely unknown. Predators of the species are also unknown. Though crested bullhead shark (Heterodontus galeatus) are known to prey upon Port Jackson shark embryos, the biggest threat is probably from other sharks such as white sharks and the broadnose sevengill shark (Notorynchus cepedianus).[10]

In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the Port Jackson shark as "Vagrant" with the qualifier "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[21]

References

- Huveneers, C. & Simpfendorfer, C. (2015). "Heterodontus portusjacksoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T39334A68625721. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T39334A68625721.en.

- Kadar, Julianna; Ladds, Monique; Mourier, Johann; Day, Joanna; Brown, Culum (2019). "Acoustic accelerometry reveals diel activity patterns in premigratory Port Jackson sharks". Ecology and Evolution. 9 (16): 8933–8944. doi:10.1002/ece3.5323. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 6706188. PMID 31462992.

- Kindersley, Dorling (2001). Animal. New York City: DK Publishing. ISBN 0-7894-7764-5.

- Carpenter, Kent E.; Luna, Susan M. (2019). Froese, R; Pauly, D. (eds.). "Heterodontus portusjacksoni (Meyer, 1793)". Fishbase. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Heterodontus portusjacksoni (Bullhead)".

- Roberts, Clive; Stewart, A. L.; Struthers, Carl D.; Barker, Jeremy; Kortet, Salme; Freeborn, Michelle (2015). The fishes of New Zealand. Vol. 2. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Papa Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780994104168. OCLC 908128805.

- Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002). International wildlife encyclopedia. New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 2027.

- M. McGrouther (October 2006). "Port Jackson Shark". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- Dianne J. Bray, 2011, Port Jackson Shark, Heterodontus portusjacksoni, in Fishes of Australia, accessed 26 Aug 2014, http://www.fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/1982

- Rebecca Sarah Thaler. "Port Jackson Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- Bass, Nathan; Mourier, Johann; Knott, Nathan; Day, Joanna; Guttridge, Tristan; Brown, Culum (2017). "Long-term migration patterns and bisexual philopatry in a benthic shark species". Marine and Freshwater Research. 68 (8): 1414–1421. doi:10.1071/MF16122. ISSN 1448-6059.

- Kadar, Julianna P.; Ladds, Monique A.; Day, Joanna; Lyall, Brianne; Brown, Culum (January 2020). "Assessment of Machine Learning Models to Identify Port Jackson Shark Behaviours Using Tri-Axial Accelerometers". Sensors. 20 (24): 7096. Bibcode:2020Senso..20.7096K. doi:10.3390/s20247096. PMC 7763149. PMID 33322308.

- "HETERODONTIFORMES", Sharks of the World, Princeton University Press, pp. 247–257, 2021-07-20, doi:10.2307/j.ctv1574pqp.16, ISBN 9780691205991, S2CID 240759913, retrieved 2021-09-11

- Mourier, Johann; Bass, Nathan Charles; Guttridge, Tristan L.; Day, Joanna; Brown, Culum (2017). "Does detection range matter for inferring social networks in a benthic shark using acoustic telemetry?". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (9): 170485. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470485M. doi:10.1098/rsos.170485. PMC 5627096. PMID 28989756.

- Pouca, Catarina Vila; Brown, Culum (2019). "Lack of social preference between unfamiliar and familiar juvenile Port Jackson sharks Heterodontus portusjacksoni". Journal of Fish Biology. 95 (2): 520–526. doi:10.1111/jfb.13982. ISSN 1095-8649. PMID 30993695. S2CID 119522453.

- Byrnes, E. E.; Brown, C. (2016). "Individual personality differences in Port Jackson sharks Heterodontus portusjacksoni". Journal of Fish Biology. 89 (2): 1142–1157. doi:10.1111/jfb.12993. ISSN 1095-8649. PMID 27228221.

- Guttridge, Tristan L.; Brown, Culum (2014). "Learning and memory in the Port Jackson shark, Heterodontus portusjacksoni". Animal Cognition. 17 (2): 415–425. doi:10.1007/s10071-013-0673-4. ISSN 1435-9456. PMID 23955028. S2CID 14511996.

- Vila Pouca, Catarina; Brown, Culum (2018). "Food approach conditioning and discrimination learning using sound cues in benthic sharks". Animal Cognition. 21 (4): 481–492. doi:10.1007/s10071-018-1183-1. ISSN 1435-9456. PMID 29691698. S2CID 19488641.

- Vila Pouca, Catarina; Gervais, Connor; Reed, Joshua; Michard, Jade; Brown, Culum (2019-06-14). "Quantity discrimination in Port Jackson sharks incubated under elevated temperatures". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 73 (7): 93. doi:10.1007/s00265-019-2706-8. ISSN 1432-0762. S2CID 189819362.

- Buttler, Mark (19 October 2011). "Man bitten by shark at Elwood beach". Herald Sun. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 10. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.