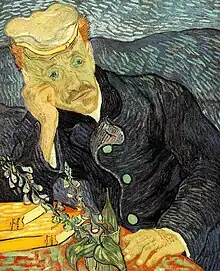

Portrait of Dr. Gachet

Portrait of Dr. Gachet is one of the most revered paintings by the Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh. It depicts Dr. Paul Gachet, a homeopathic doctor and artist[1] with whom van Gogh resided following a spell in an asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Gachet took care of Van Gogh during the final months of his life. There are two authenticated versions of the portrait, both painted in June 1890 at Auvers-sur-Oise. Both show Gachet sitting at a table and leaning his head on his right arm, but they are easily differentiated in color and style. There is also an etching.

| Portrait of Dr. Gachet | |

|---|---|

1st version | |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1890 |

| Catalogue | |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 67 cm × 56 cm (23.4 in × 22.0 in) |

| Location | Private collection |

| Portrait of Dr. Gachet | |

|---|---|

2nd version | |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1890 |

| Catalogue | |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 67 cm × 56 cm (23.4 in × 22.0 in) |

| Location | Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

The first version was acquired by the Städel in Frankfurt in 1911 and subsequently confiscated and sold by Hermann Göring. In May 1990, it was sold at auction for $82.5 million ($184.8 million today) to Ryoei Saito, making it the world's most expensive painting at that time. It then disappeared from public view and the Städel was unable to locate it in 2019. The second version was owned by Gachet and was bequeathed to France by his heirs. Despite arguments over its authenticity, it now hangs in the Musée d'Orsay, in Paris.

Background

In late 1888, Van Gogh began to experience a mental breakdown, cutting off part of his ear.[2] He stayed in hospital for a month,[2] but was not fully healed and in April 1889 he checked himself into an asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where he remained for a year.[1] Released in 1890, Van Gogh's brother Theo searched for a home for the artist. Upon the recommendation of Camille Pissarro, a former patient of the doctor who told Theo of Gachet's interests in working with artists, Theo sent Vincent to Gachet's second home in Auvers.[3]

Vincent van Gogh's first impression of Gachet was unfavorable. Writing to Theo he remarked: "I think that we must not count on Dr. Gachet at all. First of all, he is sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much, so that's that. Now when one blind man leads another blind man, don't they both fall into the ditch?"[4] However, in a letter dated two days later to their sister Wilhelmina, he relayed, "I have found a true friend in Dr. Gachet, something like another brother, so much do we resemble each other physically and also mentally."[5]

Van Gogh had a very prolific spell during his stay with Gachet, producing more than seventy paintings,[6] including the portraits of Gachet.[7]

Van Gogh's thoughts returned several times to the painting by Eugène Delacroix of Torquato Tasso in the madhouse. After a visit with Paul Gauguin to Montpellier to see Alfred Bruyas's collection in the Musée Fabre, Van Gogh wrote to Theo, asking if he could find a copy of the lithograph after the painting.[8] Three and a half months earlier, he had been thinking of the painting as an example of the sort of portraits he wanted to paint: "But it would be more in harmony with what Eugène Delacroix attempted and brought off in his Tasso in Prison, and many other pictures, representing a real man. Ah! portraiture, portraiture with the thought, the soul of the model in it, that is what I think must come."[9]

Van Gogh wrote to his sister in 1890 about the painting:

I've done the portrait of M. Gachet with a melancholy expression, which might well seem like a grimace to those who see it... Sad but gentle, yet clear and intelligent, that is how many portraits ought to be done... There are modern heads that may be looked at for a long time, and that may perhaps be looked back on with longing a hundred years later.[10]

The portraits of Dr. Gachet were completed just six weeks before Van Gogh shot himself and died from his wounds.[11]

Composition

.jpg.webp)

Van Gogh painted Gachet resting his right elbow on a red table, head in hand. Two yellow books as well as the purple medicinal herb foxglove are displayed on the table. The foxglove in the painting is a plant from which digitalis is extracted for the treatment of certain heart complaints, perhaps an attribute of Gachet as a physician.[6]

The doctor's "sensitive face", which Van Gogh wrote to Paul Gauguin carried "the heartbroken expression of our time", is described by Robert Wallace as the portrait's focus.[12] Wallace described the ultramarine blue coat of Gachet, set against a background of hills painted a lighter blue, as highlighting the "tired, pale features and transparent blue eyes that reflect the compassion and melancholy of the man."[12] Van Gogh himself said this expression of melancholy "would seem to look like a grimace to many who saw the canvas".[10]

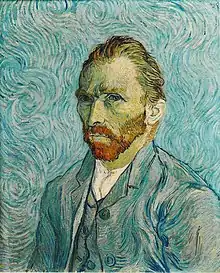

With the Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Van Gogh sought to create a "modern portrait", which he wrote to his sister "impassions me most—much, much more than all the rest of my métier."[5] Elaborating on this quote, Van Gogh scholar Jan Hulsker noted "... much later generations experience it not only as psychologically striking, but also as a very unconventional and 'modern' portrait."[13] He also wrote, "My self-portrait is done in nearly the same way but the blue is the fine blue of the Midi, and the clothes are a light lilac,"[5] which would refer to one of his final self-portraits painted in September the year previous.[13]

Van Gogh also wrote to Wilhelmina regarding the Portraits of Madame Ginoux he painted first in Arles in 1888 and again in February 1890 while at the hospital in Saint-Rémy. The second set were styled after the portrait of the same figure by Gauguin, and Van Gogh described Gachet's enthusiasm upon viewing the version painted earlier that year, which the artist had carried with him to the home in Auvers.[13] Van Gogh subsequently carried compositional elements from this portrait to that of Dr. Gachet, including the table-top with two books and pose of the figure with head leaning on one hand.[13]

Exhibition

Original version

First sold in 1897 by Van Gogh's sister-in-law Johanna van Gogh-Bonger for 300 francs, the painting was subsequently bought by Paul Cassirer (1904), Kessler (1904), and Druet (1910). In 1911, the painting was acquired by the Städel (Städtische Galerie) in Frankfurt, Germany and hung there until 1933, when the painting was put in a hidden room. The Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda confiscated the work in 1937 as part of its campaign to rid Germany of so-called degenerate art. Hermann Göring, through his agent Sepp Angerer, sold it to Franz Koenigs in Paris, together with The Quarry of Bibemus by Cézanne and Daubigny's Garden, also by van Gogh.[14] In August 1939, Koenigs transported the paintings from Paris to Knoedler's in New York. Siegfried Kramarsky fled to Lisbon in November 1939 and arrived January 1940 in New York. The paintings ended up in Kramarsky's custody, where the work was often lent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[15]

Kramarsky's family put the painting up for auction at Christie's New York on May 15, 1990,[16] where it became famous for Ryoei Saito, honorary chairman of Daishowa Paper Manufacturing Co., paying US$82.5 million for it ($75 million, plus a 10 percent buyer's commission), making it then the world's most expensive painting.[15] Two days later Saito bought Renoir's Bal du moulin de la Galette for nearly as much: $78.1 million at Sotheby's. The 75-year-old Japanese businessman commented that he would have the Van Gogh painting cremated with him after his death.[17] Though he later said he would consider giving the painting to the Japanese government or a museum, no information has been made public about the exact location and ownership of the portrait since his death in 1996.[18] Reports in 2007 said the painting was sold a decade earlier to the Austrian-born investment fund manager Wolfgang Flöttl.[19] Flöttl, in turn, had reportedly been forced by financial reversals to sell the painting to parties as yet unknown.[19] The Städel hired a private investigator to locate the painting, hoping to show it in an exhibition in 2019. It could not be found and instead the original frame still owned by the museum was put on display empty.[20]

Second version

There is a second version of the portrait which was owned by Gachet himself. In the early 1950s, along with the remainder of his personal collection of Post-Impressionist paintings, it was bequeathed to the Republic of France by his heirs.[21][22]

The authenticity of the second version has often come under scrutiny due to a number of factors. In a letter dated 3 June 1890 to Theo, Vincent mentions his work on the portrait, which includes "... a yellow book and a foxglove plant with purple flowers."[23] The subsequent letter sent to Wilhelmina also mentions "yellow novels and a foxglove flower."[5] As the yellow novels are absent from the second version of the painting, the letters clearly reference only the original version. Dr. Gachet, as well as his son, also named Paul, were amateur artists themselves. Along with original works, they often made copies of the Post-Impressionist paintings in the elder Gachet's collection, which included not only works by Van Gogh, but Cézanne, Monet, Renoir and others. These copies were self-declared, and signed under the pseudonyms Paul and Louis Van Ryssel, yet the practice has thrown the entire Gachet collection into question, including the doctor's portrait.[24] Additionally, some critics have noted the sheer number of works to emerge from Van Gogh's stay in Auvers, roughly eighty in seventy days, and questioned whether he painted them all himself.[21]

Partly in response to these accusations, the Musée d'Orsay, which holds the second version of the Gachet portrait as well as the other works originally owned by the doctor, held an exhibit in 1999 of his former collection.[21] In addition to the paintings by Van Gogh and the other Post-Impressionist masters, the exhibition was accompanied by works of the elder and younger Gachet.[25] Prior to the exhibition, the museum commissioned infrared, ultraviolet and chemical analysis of eight works each by Van Gogh, Cézanne, and the Gachets for comparison. The studies showed pigments on the Van Gogh paintings faded differently from the Gachet copies.[25] It also emerged that the Gachet paintings were drawn with outlines and filled with paint, whereas the Van Gogh and Cézanne works were painted directly to canvas.[24] Van Gogh also used the same rough canvas for all his paintings at Auvers, with the exception of The Church at Auvers (whose authenticity has never been questioned).[21] In addition to scientific evidence, defenders say that while the second version of the Portrait of Dr. Gachet is often considered to be of lesser quality than many of Van Gogh's works in Arles, it is superior in technique to anything painted by either the elder or younger Gachet.[24][25]

Dutch scholar J. B. de la Faille, who compiled the first exhaustive catalog of Van Gogh works in 1928, noted in his manuscript, "We consider this painting a very weak replica of the preceding one, missing the piercing look" of the original. Editors of the posthumous 1970 edition of Faille's book disagreed with his assessment, stating they considered both works to be of high quality.[26]

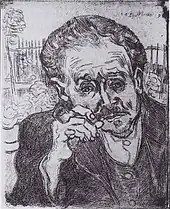

Etching

Van Gogh, introduced to etching by Gachet, made the etching Portrait of Doctor Gachet in 1890. Gachet and Van Gogh discussed creating a series of southern France themes but that never happened. This was the one and only etching, also known as L'homme à la pipe (Man with a pipe), that Van Gogh ever made. Van Gogh's brother, Theo, who received an impression of the etching, called it "a true painter's etching. No refinement in the execution, but a drawing on metal." It is a different pose than that in Van Gogh's Portrait of Dr. Gachet, owned by Musée d'Orsay. The National Gallery of Canada finds that "The undulating flow of the line is typical of the expressive quality of Van Gogh's late style." The impression owned by the National Gallery is from one of the 60 printings following Van Gogh's death by Dr. Gachet's son, Paul Gachet Jr. Gachet's collector's stamp appears on the bottom edge of the print.[27]

References

- "Vincent van Gogh". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Brettell, Richard R.; Hayes Tucker, Paul; Henderson Lee, Natalie (2009). Nineteenth- and Twentieth-century Paintings. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 126. ISBN 9781588393494. Archived from the original on 2018-09-14. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- Ravin, James; Amalric, Pierre (1997). "Paul-Ferdinand Gachet's unpublished manuscript Ophthalmia in the Armies of Europe". Documenta Ophthalmologica. 93 (1/2): 49–59. doi:10.1007/bf02569046. PMID 9476604. S2CID 20217116.

- Letter 648 Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Letter W22 Archived 2011-08-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Henley, Jon (27 January 1999). "The remarkable Dr Gachet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Le docteur Paul Gachet". Musée d'Orsay. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Letter 564 Archived 2006-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Letter 531 Archived 2016-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Letter W23 Archived 2011-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Tully, Judd (16 May 1990). "$82.5 MILLION FOR VAN GOGH". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Wallace, Robert (1969). The World of Van Gogh. New York: Time-Life Books. pp. 174–75.

- Hulsker, Jan (1990). Vincent and Theo Van Gogh: A Dual Biography. Ann Arbor, MI: Fuller Publications. pp. 420–21. ISBN 0-940537-05-2.

- Lindsay, Ivan. (2014). The History of Loot and Stolen Art: from Antiquity until the Present Day. London: Andrews UK. p. 413. ISBN 978-1-906509-56-9. Archived from the original on 2017-04-25. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- Kleiner, Carolyn (July 24, 2000). "Van Gogh's vanishing act". Mysteries of History. U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- Christie's New York May 15, 1990, lot 21 of Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture (Part 1). Sale GACHET-7068.

- Usbourne, David (27 July 1999). "Lost Van Gogh feared cremated with owner". The Independent. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "History of the Dr Gachet painting". Annaboch.com. 1990-05-15. Archived from the original on 2010-12-27. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- "Dr. Gachet" Sighting: It WAS Flöttl! Archived 2018-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, ArtsJournal

- Bailey, Martin (15 November 2019). "Where is the portrait of Dr Gachet? The mysterious disappearance of Van Gogh's most expensive painting". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Bailey, Martin (March 1999). "Cézanne joins Van Gogh for close scrutiny". The Art Newspaper: 10–12. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- Kimmelman, Michael (May 29, 1999). "Comparing the Fake and the Great". Art Review. The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- Letter 638 Archived 2011-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Lichfield, John (5 February 1999). "Arts: No cachet in a Gachet". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- Henley, Jon (28 January 1999). "The remarkable Dr Gachet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- de la Faille, J.B.; Reynal & Company (1970). The Works of Vincent van Gogh. New York: William Morrow & Company. p. 292.

- "Portrait of Doctor Gachet". Collections. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

Further reading

- Saltzman, Cynthia: Portrait of Dr. Gachet: The Story of a Van Gogh Masterpiece: Money, Politics, Collectors, Greed, and Loss. ISBN 0-670-86223-1

External links

- Musée d'Orsay: Vincent van Gogh Dr Paul Gachet

- Van Gogh, Paintings and Drawings: A Special Loan Exhibition, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on this painting (see index)

- Moffett, Charles S. Van Gogh as Critic and Self-Critic, 1973 exhibition catalog from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Podcast Finding Van Gogh, released 12 September 2019 by the Staedel Museum.

Media related to Portrait of Dr. Gachet at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Portrait of Dr. Gachet at Wikimedia Commons