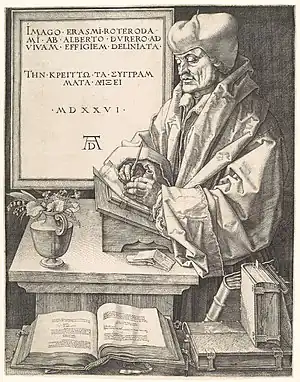

Portrait of Erasmus (Dürer)

Portrait of Erasmus is a late period 1526 copper engraving by the German artist Albrecht Dürer. The portrait was commissioned by the Dutch Renaissance humanist Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (c.1466-69 – 1536) when the two men met in the Netherlands between 1520 and 1521. Erasmus was then at the height of his renown, and required representations of himself to accompany his writings. It was not completed until some six years later, but proceeds a number of preparatory sketches made at that time.

It is not a close representation of Erasmus' physical characteristics, for which has sometimes been criticised, including by Erasmus himself, and by Martin Luther, with whom Erasmus had a prolonged and thorny relationship.[1] It is today viewed by art historians as a pioneering capture of his moral integrity, intellectualism and scholarship, and is one of the most popular and recognisable portraits of the sitter.

Commission

Erasmus was a renowned humanist scholar and theologian. He respected Dürer's stature, and seemingly greatly admired his work, but more his graphic woodcuts and drawings than his paintings.[2] On January 8, 1525, Erasmus wrote, "I wish I could also be portrayed by Dürer. Why not by such an artist? But how could it be accomplished? He began my portrait in charcoal at Brussels, but he has probably put it aside long ago. If he could do it from my medal or from memory, let him do what he has done for you, that is, add some fat". In 1528, after the portrait was complete he wrote, "is it not more wonderful to accomplish without the blandishment of colors what Apelles accomplished with their aid?"[3] The implication being that Dürer could achieve more with bare black lines than other 16th century artists -including Dürer himself- with expansive colours.[4]

They met at least three times, during Dürer's 1520-21 visit to the Netherlands. Erasmus commissioned a portrait,[5] as he required a large number of portraits of himself to send to his correspondents and admirers throughout Europe. As recorded in his dairies, Dürer sketched Erasmus a number of times in charcoal during these encounters, but it was six years before he completed the engraving.[6]

Description

Erasmus is shown in half-length, serious minded, standing and writing in his study.[7] Before him are a number of books, intended to indicate his scholarship. The books serve a deeper purpose, indicating that both men made their names as a result of developments in printing.[8]

The lilies in a vase probably refer to the purity and incorruptibility of his mind and intentions.

The Latin and Greek script behind him is framed on the wall as if a picture, and reads "This image of Erasmus of Rotterdam was drawn from life by Albrecht Dürer. The better portrait will his writings show. 1526. AD".[9]

Art historical evaluation

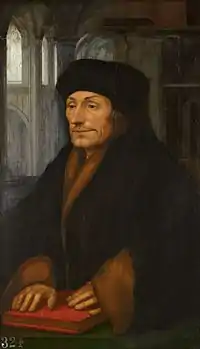

Although the work is widely known and popular, early to mid 20th art historians viewed it with reserve. Both Heinrich Wölfflin and Erwin Panofsky described it in generally favourable terms, although Wölfflin wrote that it "lacked life",[10] especially when compared to Hans Holbein's portraits of Erasmus. Similarly, Max Friedländer described it as "hesitant" and without conviction.

Dürer was not seeking to exactly reproduce the sitter's physical appearance, but more to represent "the better portrait will his writings show"; indicating that his words, rather than his physical features are the most noteworthy aspect for recording.[11] According to Panofsky, "Dürer did his best to 'characterize' Erasmus by the paraphernalia of erudition and taste, with a charming bouquet of violets and lilies-of-the-valley testifying to his love of beauty and, at the same time, serving as symbols of modesty and virginal purity."[10] Panofsky concluded that Durer "failed to capture that elusive blend of charm, serenity, ironic wit, complacency, and formidable strength that was Erasmus of Rotterdam."[12]

Erasmus himself was vocally unhappy with the final work, and in 1528, the year of Dürer's death, complained in a letter that the portrait did not physically resemble him. However, and although Erasmus often sought portraits of himself, he was rarely happy of the results. Of a minor Holbein portrait he wrote, "If Erasmus looked as young as that he would be thinking of taking a wife".[11] Martin Luther (1483-1546) also disliked the engraving, but having publicly fallen out with Erasmus at the time, dryly observed that "no one is really pleased with his own likeness".[13]

References

Notes

- Although an early supporter, by 1526 Erasmus had distanced himself from Luther in bitter terms

- A taste that may have been more influenced by his humanist favour for economy over aesthetics. See Silver; Smith, 63

- Stechow, 123

- Silver; Smith, 35

- Silver; Smith, 63

- "Erasmus of Rotterdam". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 1 September 2017

- Wölfflin, 270

- Hayum, 658

- Dürer extensively used the letters "AD", the Latinate form of his name, as his monograph in paintings, drawings and woodcuts.

- Hayum, 650

- Hayum, 654

- "Epistolarum, VII". Oxford, 1928, 376, no. 1985. Basel, 29 March 1528, to H. Botteus: "... Unde statuarius iste nactus sit effigiem mei demiror, nisi fortasse habet eam quam Quintinus Antuerpiae fudit aere. Pinxit me Durerius, sed nihil simile."

- Hayum, 655

Sources

- Hayum, Andrée. "Dürer's Portrait of Erasmus and the Ars Typographorum". Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 4, Winter, 1985

- Silver, Larry; Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. The Essential Dürer. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8122-2178-7

- Stechow, Wolfgang. Northern Renaissance Art, 1400-1600: Sources and Documents. Northwestern University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8101-0849-3

- Wölfflin, Heinrich. The Art of Albrecht Dürer. London, 1905

.jpg.webp)