Post-capitalism

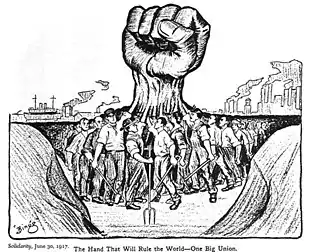

Post-capitalism is, in part, a hypothetical state in which the economic systems of the world can no longer be described as forms of capitalism. Various individuals and political ideologies have speculated on what would define such a world. According to classical Marxist and social evolutionary theories, post-capitalist societies may come about as a result of spontaneous evolution as capitalism becomes obsolete. Others propose models to intentionally replace capitalism, most notably socialism, communism, anarchism, nationalism and degrowth.

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

History

In 1993, Peter Drucker outlined a possible evolution of capitalistic society in his book Post-Capitalist Society.[1] This states that knowledge, rather than capital, land, or labor, is the new basis of wealth. The classes of a fully post-capitalist society are expected to be divided into knowledge workers or service workers, in contrast to the capitalists and proletarians of a capitalist society. Drucker estimated the transformation to post-capitalism would be completed in 2010–2020. Drucker also argued for rethinking the concept of intellectual property by creating a universal licensing system.[2]

In 2015, according to Paul Mason, several factors — the rise of income inequality, repeating cycles of boom and bust, and capitalism's contributions to climate change — led economists, political thinkers and philosophers to start seriously considering how a post-capitalistic society would look and function. Post-capitalism is expected to be made possible with further advances in automation and information technology – both of which are effectively causing production costs to trend toward zero.[3]

Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams identify a crisis in capitalism's ability and willingness to employ all members of society, arguing that: "there is a growing population of people that are situated outside formal, waged work, with minimal welfare benefits, informal subsistence work, or by illegal means".[4]

Variations

Heritage check system

Heritage check system is a socioeconomic plan that retains a market economy but removes fractional reserve lending power from banks and limits government printing of money to offset deflation. Money printed is used to buy materials to back the currency and pay for government programs in lieu of taxes, with the remainder to be split evenly among all citizens to stimulate the economy (termed a "heritage check", for which the system is named). The original author of the idea, Robert Heinlein, stated in his book For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, that the system would be self-reinforcing and would eventually result in regular heritage checks able to provide a modest living for most citizens.[5]

Economic democracy

Economic democracy is a socioeconomic philosophy that establishes democratic control of firms by their workers and social control of investment by a network of public banks.[6]

Participatory economy

In his book Of the People, By the People: The Case for a Participatory Economy, Robin Hahnel describes a post-capitalist economy called the participatory economy.[7]

Hahnel argues that a participatory economy will return empathy to our purchasing choices. Capitalism removes the knowledge of how and by whom a product was made: "When we eat a salad the market systematically deletes information about the migrant workers who picked it".[8]

Socialism

Socialism often implies common ownership of companies and a planned economy, though as an inherently pluralistic ideology, it is argued whether either are essential features.[9] In his book PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future, Paul Mason argues that centralized planning, even with the advanced technology of today, is unachievable.[3]

In UK politics, strands of Corbynism and the Labour party have adopted this 'post-capitalist' tendency.[10][11]

Permaculture

Permaculture is defined by its co-originator Bill Mollison as: "The conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive systems which have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems".[12]

PROUT

Progressive utilization theory (PROUT) is a socioeconomic and political philosophy created by the Indian philosopher and spiritual leader Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar in 1959. PROUT includes the decentralization of the economy; economic democracy; development of cooperatives; provision of all working members of society with five basic needs: food, clothing, shelter, education, medical care; and systematic solution of environmental problems through technological development and limitation of consumption.[13]

Degrowth and MMT

Modern monetary theory (MMT) could enhance the degrowth movement in transitioning to a "post-growth, post-capitalist economy", according to economic anthropologist Jason Hickel. Towards this end, he suggests that the power of "the government’s role as the issuer of currency" could be utilized to bring the economy back into balance with the natural world while at the same time reducing economic inequality by providing high quality universal basic services, implementing the rapid development of renewable energy infrastructure to completely phase out fossil fuels in a shorter period of time, and establishing a public job guarantee for 30 hours a week at a living wage doing decommodified, socially useful work in the public services sector, and also useful work in renewable energy development and ecosystem restoration. Hickel notes that providing a living wage at 30 hours a week also has the added benefit of shifting income from capital to labor. Furthermore, he adds that taxation can be used to "reduce demand in order to bring resource and energy use down to target levels," and specifically to reduce the purchasing power of the wealthy.[14]

Technology as a driver of post-capitalism

Automation

Technological change that has driven unemployment has historically been due to 'mechanical-muscle' machines, which have reduced the need for human labor. Just as the use of horses for transport and other work was gradually made obsolete by the invention of the automobile, humans' jobs have also been affected throughout history. A modern example of this technological unemployment is the replacement of retail cashiers by self-service checkouts. The invention and development of 'mechanical-mind' processes or 'brain labor' is thought to threaten jobs at an unprecedented scale, with Oxford Professors Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne estimating that 47% of US jobs are at risk of automation.[15]

Information technology

Post-capitalism is said to be possible due to major changes brought about by information technology in recent years. These changes have blurred the boundaries between work and free time[16] and loosened the relationship between work and wages. Significantly, information is corroding the market's ability to form prices correctly. Information is abundant and information goods are freely replicable. Goods such as music, software or databases do have a production cost, but once made can be copied infinitely. If the normal price mechanism of capitalism prevails, then the price of any good which has essentially no cost of reproduction will fall towards zero.[17] This lack of scarcity of those things is a problem in those models, which try to counter by developing monopolies in the form of giant tech companies to keep information scarce and commercial. But many significant commodities in the digital economy are now free and open-source, such as Linux, Firefox, and Wikipedia.[18]

See also

- Anti-capitalism

- Capitalist realism

- Commons-based peer production

- Criticism of capitalism

- Degrowth

- Distributism

- Eco-communalism

- Economic history of the world

- Evolutionary economics

- Historical materialism

- Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

- Late capitalism

- P2P economic system

- Post-democracy

- Post-industrial society

- Post-scarcity economy

- Post-work society

- Resource-based economy

- Sharing economy

- Social democracy

- Socialist calculation debate

- Sociocultural evolution

- Tang ping ("lying flat")

- Technological unemployment § Solutions

- The Venus Project

- The Zeitgeist Movement

References

- Drucker, Peter F. (1993). Post-Capitalist Society. HarperInformation. ISBN 978-0-7506-0921-0.

- Schwartz, Peter (1 March 1993). "Post-Capitalist". WIRED. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Mason, Paul (2015). PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future. Allen Lane. ISBN 9781846147388.

- Srnicek, Nick; Williams, Alex. Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. Verso Books. pp. 103–104. ISBN 9781784780968

- Heinlein, Robert (2003). For Us, The Living. Scribner. pp. 233. ISBN 978-0-7432-5998-9.

- Schweickart, David (2002). After Capitalism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-7425-1299-3.

- Hahnel, Robert (2012). Of the People, By the People: The Case for a Participatory Economy. AK Press Distribution. ISBN 978-0983059769.

- Albert, Michael; Hahnel, Robin. "Participatory Planning" (PDF). Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Wright, Tony (1986) Socialisms: theories and practices. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192191885.

- Pitts, F. and Dinerstein, A. (2017). Corbynism's conveyor belt of ideas: Postcapitalism and the politics of social reproduction. Capital & Class, 41(3), pp.423-434.

- Peck, Tom (2016-08-30). "Jeremy Corbyn promises to 'rebuild Britain' with digital manifesto". Independent. Independent. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "What is Permaculture ?". The Permaculture Research Institute. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- Sarkar, Prabhat (1992). Proutist economics - Discourses on economic liberation. India: Ananda Marga. ISBN 978-81-7252-003-8.

- Hickel, Jason (September 23, 2020). "Degrowth and MMT: a thought experiment". jasonhickel.org. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

MMT proposals align elegantly with one of degrowth's key observations, namely, that if growthism depends on the perpetual creation of artificial scarcity, then by reversing artificial scarcity – by providing public abundance – we can dismantle the growth imperative. As Giorgos Kallis has put it, "capitalism cannot survive under conditions of abundance". MMT provides an opportunity for us to create a post-growth, post-capitalist economy.

- Frey, Carl Benedikt; Osborne, Michael A (2017-01-01). "The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 114: 254–280. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.416. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019. ISSN 0040-1625.

- N. Korody. "Architecture after capitalism, in a world without work". Retrieved 25 Jun 2017.

- P. Mason (2015-07-17). "Three dynamics leading to post-capitalism". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 Jun 2017.

- Mason, Paul (17 July 2015). "The end of capitalism has begun". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

Further reading

- Albert, Michael. Parecon: Life After Capitalism. London: Verso, 2003.

- Ankerl, Guy C. Beyond Monopoly Capitalism and Monopoly Socialism: Distributive Justice in a Competitive Society. Cambridge MA: Schenkman, 1978.

- The Associative Economy: Insights beyond the Welfare System and into Post-Capitalism.

- Bell, Karen (2015). "Can the capitalist economic system deliver environmental justice?". Environmental Research Letters. 10 (12): 125017. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/125017.

- Benkler, Yochai (2006). The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12577-1.

- Blühdorn, Ingolfur (2017). "Post-capitalism, post-growth, post-consumerism? Eco-political hopes beyond sustainability". Global Discourse. 7 (1): 42–61. doi:10.1080/23269995.2017.1300415.

- Bowels, Samuel; Carlin, Wendy (2021). "Shrinking capitalism: components of a new political economy paradigm". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 37 (4): 794–810. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grab029.

- Frase, Peter (2016). Four futures: Life After Capitalism. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1781688137.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). A Postcapitalist Politics. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816648047

- Healy, Stephen (2020). "Alternative Economies". International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second Edition): 111–117. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10049-6.

- Hickel, Jason (2019). "Is it possible to achieve a good life for all within planetary boundaries?". Third World Quarterly. 40 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1535895.

- Hickel, Jason (2020). Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Penguin Random House. ISBN 9781785152498.

- Longhurst, Noel; Avelino, Flor; Wittmayer, Julia; Weaver, Paul; Dumitru, Adina; Hielscher, Sabine; Cipolla, Carla; Afonso, Rita; Kunze, Iris; Elle, Morten (2016). "Experimenting with alternative economies: four emergent counter-narratives of urban economic development". Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 22: 69–74. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.006.

- Mason, Paul (2015). PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future, London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9781846147388.

- Monticelli, Lara (2018). "Embodying Alternatives to Capitalism in the 21st Century". tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society. 16 (2): 501–517. doi:10.31269/triplec.v16i2.1032.

- Rifkin, Jeremy (2014). The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1137278463

- Shutt, Harry (2010). Beyond the Profits System: Possibilities for the Post-Capitalist Era. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1848134171.

- Srnicek, Nick; Williams, Alex (2015). Inventing the future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-7847-8096-8.

- Steele, David Ramsay (1999). From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. ISBN 978-0875484495.

- Wright, Erik O. Envisioning Real Utopias. London: Verso, 2010.

.jpg.webp)