Conversion therapy

Conversion therapy is the pseudoscientific practice of attempting to change an individual's sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to align with heterosexual and cisgender norms.[1] Methods that have been used to this end include forms of brain surgery, surgical or hormonal castration, aversive treatments such as electric shocks, nausea-inducing drugs, hypnosis, counseling, spiritual interventions, visualization, psychoanalysis, and arousal reconditioning.

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender |

|

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

There is a scientific consensus that conversion therapy is ineffective at changing a person's sexual orientation or gender identity and that it frequently causes significant, long-term psychological harm in individuals who undergo it.[2] The position of current evidence-based medicine and clinical guidance is that homosexuality, bisexuality and gender variance are natural and healthy aspects of human sexuality.[2][3] Historically, conversion therapy was the treatment of choice for individuals who disclosed same-sex attractions or exhibited gender nonconformity, which were formerly assumed to be pathologies by the medical establishment.[3] When performed today, conversion therapy may constitute fraud and when performed on minors, a form of child abuse; it has been described by experts as torture, cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, and contrary to human rights.

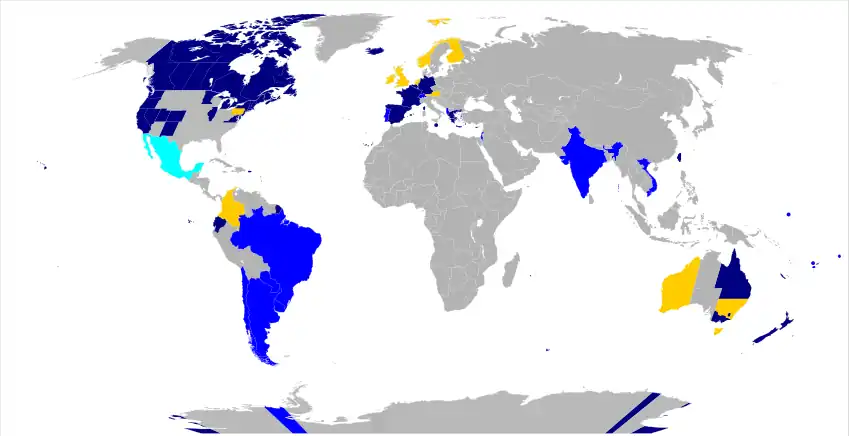

An increasing number of jurisdictions around the world have passed laws against conversion therapy.[4]

Terminology

Medical professionals and activists consider "conversion therapy" a misnomer, as it does not constitute a legitimate form of therapy.[5] Alternative terms include sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE)[5] and gender identity change efforts (GICE)[5]—together, sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts (SOGICE).[6] According to researcher Douglas C. Haldeman, SOCE and GICE should be considered together because both rest on the assumption "that gender-related behavior consistent with the individual's birth sex is normative and anything else is unacceptable and should be changed".[7] "Reparative therapy" may refer to conversion therapy in general,[5] or to a subset thereof.[8]

Advocates of conversion therapy do not necessarily use the term either, instead using phrases such as "healing from sexual brokenness"[9][10] and "struggling with same-sex attraction".[11]

History

Sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE)

The term homosexual was coined by German-speaking Hungarian writer Karl Maria Kertbeny and was in circulation by the 1880s.[12][4] Into the middle of the twentieth century, competing views of homosexuality were advanced by psychoanalysis versus academic sexology. Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, viewed homosexuality as a form of arrested development. Later psychoanalysts followed Sandor Rado, who argued that homosexuality was a "phobic avoidance of heterosexuality caused by inadequate early parenting".[4] This line of thinking was popular in psychiatric models of homosexuality based on the prison population or homosexuals seeking treatment. In contrast, sexology researchers such as Alfred Kinsey argued that homosexuality was a normal variation in human development. In 1970, gay activists confronted the American Psychiatric Association, persuading the association to reconsider whether homosexuality should be listed as a disorder. The APA delisted homosexuality in 1973, which contributed to shifts in public opinion on homosexuality.[4]

Despite their lack of scientific backing, some socially or religiously conservative activists continued to argue that if one person's sexuality could be changed, homosexuality was not a fixed class such as race. Borrowing from discredited psychoanalytic ideas about the cause of homosexuality, some of these individuals offered conversion therapy.[4] In 2001, conversion therapy attracted attention when Robert L. Spitzer published a non-peer-reviewed study asserting that some homosexuals could change their sexual orientation. Many researchers made methodological criticisms of the study, which Spitzer later repudiated.[4]

Gender identity change efforts (GICE)

Gender Identity Change Efforts (GICE) refer to practices of healthcare providers and religious counselors with the goal of attempting to alter a person's gender identity or expression to conform to social norms. Examples include aversion therapy, cognitive restructuring, and psychoanalytic and talk therapies.[13] Western medical-model narratives have historically institutionalized transphobia: systemically favoring a binary gender model and pathologizing gender diversity and non-conformity.[14] This aided the development and proliferation of GICE.[15]

Early interventions were rooted in psychoanalytic hypotheses.[16] Robert Stoller advanced the theory that gender-nonconforming behavior and expression in children assigned male at birth (AMAB) was caused by being overly close to their mother. Richard Green continued his research; his methods for altering behavior included having the father spend more time with the child and mother less, expecting both to exhibit stereotypical gender roles, and having them praise their child's masculine behaviors, and shame their feminine and gender-nonconforming ones. These interventions resulted in depression in the children and feelings of betrayal from parents that the treatments failed.[16]

In the 1970s, UCLA psychologist Richard Green recruited Ole Ivar Lovaas to adapt the techniques of ABA therapy to attempt to prevent children from becoming transsexuals.[17] Deemed the "Feminine Boy Project", the treatments used operant conditioning to reward gender-conforming behaviors, and punish gender non-conforming behaviors.[17] They recruited George Rekers as a behavioral therapist for the project.[17] The project published several studies focusing on one subject and claiming that the child had been "cured" after 60 treatment sessions.[17][18][19][20][21] However, decades later at the age of 38, the subject died of suicide, with the family blaming psychological trauma from the program.[22][23]

Kenneth Zucker at CAMH adopted Richard Green's methods, but narrowed the scope to attempting to prevent the child from identifying as transgender. His model used the same interventions as Green with the addition of psychodynamic therapy.[16] In January 2015, members of Rainbow Health Ontario, a provincial health promotion and navigation organization, approached CAMH expressing their concerns regarding Zucker's clinic.[24] Rainbow Health Ontario submitted a review of academic literature and clinical practices for transgender youth, and expressed concern that the gender identity clinic was not following accepted practices.[25] Others linked the Gender Identity Clinic's practices to suicide of transgender youth caused by conversion therapy, and referenced the high-profile case of Leelah Alcorn, a transgender teen from Ohio.[24] In November 2015, an external review of the clinic was published.[26] The review noted numerous strengths of the clinic, but also described it as an insular entity with an approach dissimilar from other clinics and described it as being out of step with current best practices, including WPATH SOC Version 7.[26] After the review, CAMH shut down the clinic and fired Zucker. Kwame McKenzie, medical director of CAMH's child, youth, and family services, said "We want to apologize for the fact that not all of the practices in our childhood gender identity clinic are in step with the latest thinking" and that Zucker is, "no longer at CAMH."[27]

Some clinicians have begun using "gender exploratory therapy" as an alternative to gender-affirming approaches for youth with gender dysphoria.[28] Gender exploratory therapy uses talk therapy in an attempt to find pathological roots for gender dysphoria.[28] In a September 2022 review of gender exploratory therapy, bioethicist Florence Ashley found strong similarities to "conversion practices".[28]

Motivations

A frequent motivation for adults who pursue conversion therapy is their religious beliefs, especially evangelical Christianity and Orthodox Judaism, that disapprove of same-sex relations. These adults prioritize maintaining a good relationship with their family and religious community.[29] Adolescents who are pressured by their families into undergoing conversion therapy also typically come from a conservative religious background.[29] Youth from families with low socioeconomic status are also more likely to undergo conversion therapy.[30]

Theories and techniques

As societal attitudes toward homosexuality have become more tolerant over time, the most harsh conversion therapy methods such as aversion have been reduced. Secular conversion therapy is offered less often due to reduced medical pathologization of homosexuality, and religious practitioners have become more dominant.[31]

Aversion therapy and behaviorism

Aversion therapy used on homosexuals included electric shock and nausea-inducing drugs during presentation of same-sex erotic images. Cessation of the aversive stimuli was typically accompanied by the presentation of opposite-sex erotic images, with the objective of strengthening heterosexual feelings.[32] Another method used was the covert sensitization method, which involves instructing patients to imagine vomiting or receiving electric shocks, writing that only single case studies have been conducted, and that their results cannot be generalized. Haldeman writes that behavioral conditioning studies tend to decrease homosexual feelings, but do not increase heterosexual feelings, citing Rangaswami's "Difficulties in arousing and increasing heterosexual responsiveness in a homosexual: A case report", published in 1982, as typical in this respect.[33]

Aversion therapy was developed in Czechoslovakia between 1950 and 1962 and in the British Commonwealth from 1961 into the mid-1970s. In the context of the Cold War, Western psychologists ignored the poor results of their Czechoslovak counterparts, who had concluded that aversion therapy was not effective by 1961 and recommended decriminalization of homosexuality instead.[34] Some men in the United Kingdom were offered the choice between prison and undergoing aversion therapy. It was also offered to a few British women, but was never the standard treatment for either homosexual men or women.[35]

In the 1970s, behaviorist Hans Eysenck was one of the main advocates of counterconditioning with malaise-inducing drugs and electric shock for homosexuals. He wrote that this type of therapy was successful in nearly 50% of cases. However, his studies were disputed.[36] Behavior therapists, including Eysenck, used aversive methods. This led to a protest against Eysenck by gay activist Peter Tatchell in a London Medical Group Symposium in 1972. Tatchell said that the therapy promoted by Eysenck was a form of torture.[36] Tatchell denounced Eysenck's form of behavioral therapy as inducing depression and suicide among gay men who were subjected to it.[37]

Brain surgery

In the 1940s and 1950s, U.S. neurologist Walter Freeman popularized the ice-pick lobotomy as a treatment for homosexuality. He personally performed as many as 3,439[38] lobotomy surgeries in 23 states, of which 2,500 used his ice-pick procedure,[39] despite the fact that he had no formal surgical training.[40]

In West Germany, a type of brain surgery usually involving destruction of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus was done to some homosexual men. The practice was criticized by sexologist Volkmar Sigusch.[41]: 526

Castration and transplantation

In early twentieth century Germany experiments were carried out in which homosexual men were subjected to unilateral orchiectomy and testicles of heterosexual men were transplanted. These operations were a complete failure.[42]

Surgical castration of homosexual men was widespread in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century and was also practiced in the United States.[43] SS leader Heinrich Himmler ordered homosexual men to be sent to concentration camps because he did not consider a time-limited prison sentence was sufficient to eliminate homosexuality.[44] Although theoretically voluntary, some homosexuals were subject to severe pressure and coercion to agree to castration. There was no age limit; some boys as young as 16 were castrated. Those who agreed to castration after a Paragraph 175 conviction were exempted from being transferred to a concentration camp after completing their legal sentence.[45] Some concentration camp prisoners were also subjected to castration.[46] An estimated 400 to 800 men were castrated.[47]

Endocrinologist Carl Vaernet attempted to change homosexual concentration camp prisoners' sexual orientations by implanting a pellet that released testosterone. Most of the victims, non-consenting prisoners at Buchenwald, died shortly thereafter.[48][49]

An unknown number of men were castrated in West Germany and chemical castration was used in other Western countries, notably against Alan Turing in the United Kingdom.[50]

Ex-gay/ex-trans ministry

Some sources describe ex-gay and ex-trans ministries as a form of conversion therapy, while others state that ex-gay organizations and conversion therapy are distinct methods of attempting to convert gay people to heterosexuality.[51][52][53][54] The umbrella organization Exodus International in the United States ceased activities in June 2013, and the three member board issued a statement which repudiated its aims and apologized for the harm their pursuit has caused to LGBT people.[55] Ex-gay/ex-trans organizations often overlap and portray being trans as inherently sinful or against God's design, or pathologize gender variance as due to trauma, social contagion, or "gender ideology."[56][57]

Hypnosis

Hypnosis was used in conversion therapy since the 19th century by Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Albert von Schrenck-Notzing. In 1967, Canadian psychiatrist Peter Roper published a case study of treating 15 homosexuals (some of which would probably be considered bisexuals by modern standards) with hypnosis. Allegedly, 8 showed "marked improvement" (they reportedly lost sexual attraction towards the same sex altogether), 4 mild improvements (decrease of "homosexual tendencies"), and 3 no improvement after hypnotic treatment; he concluded that "hypnosis may well produce more satisfactory results than those obtainable by other means", depending on the hypnotic susceptibility of the subjects.[58]

Psychoanalysis

Haldeman writes that psychoanalytic treatment of homosexuality is exemplified by the work of Irving Bieber et al. in Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals. They advocated long-term therapy aimed at resolving the unconscious childhood conflicts that they considered responsible for homosexuality. Haldeman notes that Bieber's methodology has been criticized because it relied upon a clinical sample, the description of the outcomes was based upon subjective therapist impression, and follow-up data were poorly presented. Bieber reported a 27% success rate from long-term therapy, but only 18% of the patients in whom Bieber considered the treatment successful had been exclusively homosexual to begin with, while 50% had been bisexual. In Haldeman's view, this makes even Bieber's unimpressive claims of success misleading.[59]

Haldeman discusses other psychoanalytic studies of attempts to change homosexuality. Curran and Parr's "Homosexuality: An analysis of 100 male cases", published in 1957, reported no significant increase in heterosexual behavior. Mayerson and Lief's "Psychotherapy of homosexuals: A follow-up study of nineteen cases", published in 1965, reported that half of its 19 subjects were exclusively heterosexual in behavior four and a half years after treatment, but its outcomes were based on patient self-report and had no external validation. In Haldeman's view, those participants in the study who reported change were bisexual at the outset, and its authors wrongly interpreted capacity for heterosexual sex as change of sexual orientation.[60]

Reparative therapy

The term "reparative therapy" has been used as a synonym for conversion therapy generally, but according to Jack Drescher it properly refers to a specific kind of therapy associated with the psychologists Elizabeth Moberly and Joseph Nicolosi.[8] The term reparative refers to Nicolosi's postulate that same-sex attraction is a person's unconscious attempt to "self-repair" feelings of inferiority.[61][62]

Marriage therapy

Previous editions of the World Health Organization's ICD included "sexual relationship disorder", in which a person's sexual orientation or gender identity makes it difficult to form or maintain a relationship with a sexual partner. The belief that their sexual orientation has caused problems in their relationship may lead some people to turn to a marriage therapist for help to change their sexual orientation.[63] Sexual orientation disorder was removed from the most recent ICD, ICD-11, after the Working Group on Sexual Disorders and Sexual Health determined that its inclusion was unjustified.[64]

Gender exploratory therapy

Gender exploratory therapy, or GET, is a form of conversion therapy in which the administrator attempts to delay transition (both medical and social) for as long as possible, often indefinitely. This is done in an effort to get the patient to desist altogether, and is undertaken using the pretext of taking an extended period of time to explore potential causes for the patient identifying as a different gender from their assigned sex at birth which are then used to deny access to treatment entirely, including mental health issues, trauma, sexual fetishism, internalized bigotry, and autism.[65][66][67] Gender exploratory therapy is often mandated or recommended for use on gender dysphoric patients in jurisdictions where access to gender-affirming healthcare is banned or heavily restricted.

Effects

There is a scientific consensus that conversion therapy is ineffective at changing a person's sexual orientation.[2] Advocates of conversion therapy rely heavily on testimonials and retrospective self-reports as evidence of effectiveness. Studies purporting to validate the effectiveness of efforts to change sexual orientation or gender identity have been criticized for methodological flaws.[68] After conversion therapy has failed to change someone's sexual orientation or gender identity, participants often feel increased shame that they already felt over their sexual orientation or gender identity.[29]

Conversion therapy can cause significant, long-term psychological harm.[2] This includes significantly higher rates of depression, substance abuse, and other mental health issues in individuals who have undergone conversion therapy than their peers who did not,[69][70] including a suicide attempt rate nearly twice that of those who did not.[71] Modern-day practitioners of conversion therapy—primarily from a conservative religious viewpoint—disagree with current evidence-based medicine and clinical guidance that does not view homosexuality and gender variance as unnatural or unhealthy.[2][3]

In 2020, ILGA world published a world survey and report Curbin Deception listing consequences and life-threatening effects by associating specific public testimonies with different types of methods used to practice conversion therapies.[72]

A 2022 study estimated that conversion therapy of youth in the United States cost $650.16 million annually with an additional $9.5 billion in associated costs such as increased suicide and substance abuse.[70] Youth who undergo conversion therapy from a religious provider have more negative mental health outcomes than those who had consulted a licensed healthcare provider.[29]

Public opinion

A 2020 survey carried out on US adults found majority support for banning conversion therapy for minors.[73]

A 2022 YouGov poll found majority support in England, Scotland, and Wales for a conversion therapy ban for both sexual orientation and gender identity, with opposition ranging from 13 to 15 percent.[74]

Legal status

Some jurisdictions have criminal bans on the practice of conversion therapy, including Canada, Ecuador, France,[75] Germany, Malta, Mexico and Spain.[76] In other countries, including Albania, Brazil, Chile, Vietnam and Taiwan, medical professionals are barred from practicing conversion therapy.[77]

In some states, lawsuits against conversion therapy providers for fraud have succeeded, but in other jurisdictions those claiming fraud must prove that the perpetrator was intentionally dishonest. Thus, a provider who genuinely believes conversion therapy is effective could not be convicted.[78]

Conversion therapy on minors may amount to child abuse.[79][80][81]

Human rights

In 2020 the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims released an official statement that conversion therapy is torture.[79] The same year, UN Independent Expert on sexual orientation and gender identity, Victor Madrigal-Borloz, said that conversion therapy practices are "inherently discriminatory, that they are cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, and that depending on the severity or physical or mental pain and suffering inflicted to the victim, they may amount to torture". He recommended that it should be banned across the world.[82] In 2021 Ilias Trispiotis and Craig Purshouse argue that conversion therapy violates the prohibition against degrading treatment under Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, leading to a state obligation to prohibit it.[77][83] In February 2023 Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović, qualified those practices as “irreconcilable with several guarantees under the European Convention on Human Rights" and having no place in a human rights-based society urging the Member States of the Council of Europe to ban them for both adults and minors,[84] later in July 2023 she advocated for clear actions during a public hearing at the European Parliament studying different approaches to legally ban "conversion therapies" in the European Union.[85]

In media

Efforts to change sexual orientation have been depicted and discussed in popular culture and various media. More recent examples include: Boy Erased, The Miseducation of Cameron Post, Book of Mormon musical, Ratched, and documentary features Pray Away, Homotherapy: A Religious Sickness[86][87].

Medical views

National health organizations around the world have uniformly denounced and criticized sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts.[88][89][90] They state that there has been no scientific demonstration of "conversion therapy's" efficacy.[52][91][92][93] They find that conversion therapy is ineffective, risky and can be harmful. Anecdotal claims of cures are counterbalanced by assertions of harm, and the American Psychiatric Association, for example, cautions ethical practitioners under the Hippocratic oath to do no harm and to refrain from attempts at conversion therapy.[92] Furthermore, they state that conversion therapy is harmful and that it often exploits individual's guilt and anxiety, thereby damaging self-esteem and leading to depression and even suicide.[94] There is also concern in the mental health community that the advancement of conversion therapy can cause social harm by disseminating inaccurate views about gender identity, sexual orientation, and the ability of LGBT people to lead happy, healthy lives.[89] Various medical bodies prohibit their members from practicing conversion therapy.[95]

See also

References

- Fenaughty, John; Tan, Kyle; Ker, Alex; Veale, Jaimie; Saxton, Peter; Alansari, Mohamed (January 2023). "Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Change Efforts for Young People in New Zealand: Demographics, Types of Suggesters, and Associations with Mental Health". Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 52 (1): 149–164. doi:10.1007/s10964-022-01693-3. ISSN 0047-2891. PMC 9813061. PMID 36301377.

- Higbee, Madison; Wright, Eric R.; Roemerman, Ryan M. (2022). "Conversion Therapy in the Southern United States: Prevalence and Experiences of the Survivors". Journal of Homosexuality. 69 (4): 612–631. doi:10.1080/00918369.2020.1840213. PMID 33206024. S2CID 227039714.

- Haldeman 2022, p. 5.

- Drescher, Jack; Schwartz, Alan; Casoy, Flávio; McIntosh, Christopher A.; Hurley, Brian; Ashley, Kenneth; Barber, Mary; Goldenberg, David; Herbert, Sarah E.; Lothwell, Lorraine E.; Mattson, Marlin R.; McAfee, Scot G.; Pula, Jack; Rosario, Vernon; Tompkins, D. Andrew (2016). "The Growing Regulation of Conversion Therapy". Journal of Medical Regulation. 102 (2): 7–12. doi:10.30770/2572-1852-102.2.7. PMC 5040471. PMID 27754500.

- Haldeman 2022, p. 4.

- Csabs, C., Despott, N., Morel, B., Brodel, A., Johnson, R. 'The SOGICE Survivor Statement', 2018.

- Haldeman 2022, p. 8.

- Drescher 2000, p. 152

- Lee, Jin (1 January 2019). "Diversity or a flavor of diversity?". Gateway Journalism Review. 47 (352): 34–35. Gale A586241649.

- Stephens, John Bryant (1997). Conflicts over homosexuality in the United Methodist Church: Testing theories of conflict analysis and resolution (Thesis). OCLC 41964052. ProQuest 304408101.

- Creek, S. J.; Dunn, Jennifer L. (2012). "'Be Ye Transformed': The Sexual Storytelling of Ex-gay Participants". Sociological Focus. 45 (4): 306–319. doi:10.1080/00380237.2012.712863. JSTOR 41633922. S2CID 144699323.

- Whisnant 2016, p. 20.

- Rivera & Pardo 2022, p. 52.

- Rivera & Pardo 2022, p. 53.

- Rivera & Pardo 2022, p. 56.

- Rivera & Pardo 2022, p. 58.

- Silberman, Steve (2016). Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. New York City, NY: Avery. pp. 319–321. ISBN 978-0399185618.

- Rekers, George A.; Lovaas, O. Ivar (1974). "Behavioral treatment of deviant sex-role behaviors in a male child". Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 7 (2): 173–190. doi:10.1901/jaba.1974.7-173. PMC 1311956. PMID 4436165.

- Rekers, George A.; Lovaas, O. Ivar; Low, Benson (June 1974). "The behavioral treatment of a 'transsexual' preadolescent boy". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2 (2): 99–116. doi:10.1007/BF00919093. PMID 4430820. S2CID 23599014.

- Rekers, George A.; Bentler, Peter M.; Rosen, Alexander C.; Lovaas, O. Ivar (Spring 1977). "Child gender disturbances: A clinical rationale for intervention". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 14 (1): 2–11. doi:10.1037/h0087487.

- Rekers, George A.; Rosen, Alexander C.; Lovaas, O. Ivar; Bentler, Peter M. (February 1978). "Sex-role stereotypy and professional intervention for childhood gender disturbance". Professional Psychology. 9 (1): 127–136. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.9.1.127.

- Szalavitz, Maia (8 June 2011). "The 'Sissy Boy' Experiment: Why Gender-Related Cases Call for Scientists' Humility". Time Magazine. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- Bronstein, Scott; Joseph, Jessi (10 June 2011). "Therapy to change 'feminine' boy created a troubled man, family says". CNN. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- Singal, Jesse (7 February 2016). "How the Fight Over Transgender Kids Got a Leading Sex Researcher Fired". New York Magazine. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- Ashley, Florence (2022). Banning Transgender Conversion Practices: A Legal and Policy Analysis. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0774866958.

- "External Review of the Gender Identity Clinic of the Child, Youth and Family Services in the Underserved Populations Program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health" (PDF). CAMH. 26 November 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- Ubelacker, Sheryl (15 December 2015). "CAMH to 'wind down' controversial gender identity clinic services". The Globe and Mail. Canadian Press. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Ashley, Florence (6 September 2022). "Interrogating Gender-Exploratory Therapy". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 18 (2): 472–481. doi:10.1177/17456916221102325. PMC 10018052. PMID 36068009. S2CID 252108965.

- Haldeman 2022, p. 9.

- Haldeman 2022, p. 11.

- Andrade, G.; Campo Redondo, M. (2022). "Is conversion therapy ethical? A renewed discussion in the context of legal efforts to ban it". Ethics, Medicine and Public Health. 20: 100732. doi:10.1016/j.jemep.2021.100732.

- Haldeman 1991, p. 152

- Haldeman 1991, pp. 152–153

- Davison, Kate (2021). "Cold War Pavlov: Homosexual aversion therapy in the 1960s". History of the Human Sciences. 34 (1): 89–119. doi:10.1177/0952695120911593. S2CID 218922981.

- Spandler, Helen; Carr, Sarah (2022). "Lesbian and bisexual women's experiences of aversion therapy in England". History of the Human Sciences. 35 (3–4): 218–236. doi:10.1177/09526951211059422. PMC 9449443. PMID 36090521. S2CID 245753251.

- Rolls 2019, p. .

- Spandler, Helen; Carr, Sarah (2022). "Lesbian and bisexual women's experiences of aversion therapy in England". History of the Human Sciences. 35 (3–4): 218–236. doi:10.1177/09526951211059422. PMC 9449443. PMID 36090521.

- Day, Elizabeth (13 January 2008). "He was bad, so they put an ice pick in his brain..." The Observer.

- "Top 10 Fascinating And Notable Lobotomies". listverse.com. 24 June 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- Rowland, Lewis (April 2005). "Walter Freeman's Psychosurgery and Biological Psychiatry: A Cautionary Tale". Neurology Today. 5 (4): 70–72. doi:10.1097/00132985-200504000-00020.

- Rieber, Inge; Sigusch, Volkmar (1979). "Psychosurgery on sex offenders and sexual "deviants" in West Germany". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 8 (6): 523–527. doi:10.1007/BF01541419. ISSN 1573-2800. PMID 391177. S2CID 41463669.

- Schmidt 1985, pp. 133–134.

- Lehring, Gary (2010). Officially Gay: The Political Construction Of Sexuality. Temple University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4399-0399-5.

- Zinn 2020b, pp. 11–12.

- Wachsmann 2015, p. 147.

- Weindling 2015, p. 30.

- Schwartz 2021, p. 383.

- Whisnant 2016, p. 223.

- Weindling 2015, pp. 183–184.

- Huneke, Samuel Clowes (2022). States of Liberation: Gay Men between Dictatorship and Democracy in Cold War Germany. University of Toronto Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-4875-4213-9.

- Drescher & Zucker 2006, pp. 126, 175

- Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation & Youth: A Primer for Principals, Educators and School Personnel (PDF), Just the Facts Coalition, 1999, retrieved 14 May 2010

- Haldeman 1991, pp. 149, 156–159

- Jones & Yarhouse 2007, p. 374

- Chambers, Alan, I Am Sorry, Exodus International, archived from the original on 23 June 2013, retrieved 22 June 2013

- Robinson, Christine M.; Spivey, Sue E. (17 June 2019). "Ungodly Genders: Deconstructing Ex-Gay Movement Discourses of 'Transgenderism' in the US". Social Sciences. 8 (6): 191. doi:10.3390/socsci8060191.

- Jones, Tiffany; Jones, Timothy W.; Power, Jennifer; Pallotta-Chiarolli, Maria; Despott, Nathan (3 September 2022). "Mis-education of Australian Youth: exposure to LGBTQA+ conversion ideology and practises". Sex Education. 22 (5): 595–610. doi:10.1080/14681811.2021.1978964. S2CID 241018465.

- Roper, P. (11 February 1967). "The effects of hypnotherapy on homosexuality". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 96 (6): 319–327. PMC 1935956. PMID 6017544.

- Haldeman 1991, pp. 150–151

- Haldeman 1991, pp. 151, 256

- Hicks, Karolyn A. (December 1999). "'Reparative' Therapy: Whether Parental Attempts to Change a Child's Sexual Orientation Can Legally Constitute Child Abuse". American University Law Review. 49 (2): 505–547.

- Bright 2004, pp. 471–481

- Rosik, Christopher H (January 2003). "Motivational, ethical, and epistemological foundations in the treatment of unwanted homoerotic attraction". Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 29 (1): 13–28. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb00379.x. OCLC 5154888155. PMID 12616795.

- Reed, Geoffrey M.; Drescher, Jack; Krueger, Richard B.; Atalla, Elham; Cochran, Susan D.; First, Michael B.; Cohen‐Kettenis, Peggy T.; Arango‐de Montis, Iván; Parish, Sharon J.; Cottler, Sara; Briken, Peer (2016). "Disorders related to sexuality and gender identity in the ICD‐11: revising the ICD‐10 classification based on current scientific evidence, best clinical practices, and human rights considerations". World Psychiatry. 15 (3): 205–221. doi:10.1002/wps.20354. PMC 5032510. PMID 27717275.

- "Cutting through the Lies and Misinterpretations about the Updated Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People". Science Based Medicine.

- "Unpacking 'gender exploratory therapy,' a new form of conversion therapy". Xtra Magazine. 13 January 2023.

- "How Therapists Are Trying to Convince Children That They're Not Actually Trans". Slate. 2 May 2023.

- Haldeman 2022, p. 7.

- Christensen, Jen (8 March 2022). "Conversion therapy is harmful to LGBTQ people and costs society as a whole, study says". CNN. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- Forsythe, Anna; Pick, Casey; Tremblay, Gabriel; Malaviya, Shreena; Green, Amy; Sandman, Karen (2022). "Humanistic and Economic Burden of Conversion Therapy Among LGBTQ Youths in the United States". JAMA Pediatrics. 176 (5): 493–501. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0042. PMC 8902682. PMID 35254391. S2CID 247252995.

- thisisloyal.com, Loyal |. "LGB people who have undergone conversion therapy almost twice as likely to attempt suicide". Williams Institute. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- Craig, Elaine (2021). "The Legal Regulation of Sadomasochism and the So-Called 'Rough Sex Defence'". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4082097. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 248256272.

- Flores, Andrew R.; Mallory, Christy; Conron, Kerith J. (2020). "Public attitudes about emergent issues in LGBTQ rights: Conversion therapy and religious refusals". Research & Politics. 7 (4): 205316802096687. doi:10.1177/2053168020966874. S2CID 229001894.

- "The majority of Welsh people support a ban on trans conversion therapy in Wales | YouGov". yougov.co.uk. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- "France Passed Law To Protect LGBTQ People From "Conversion Therapy"". LQIOO. 3 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- Branch, Legislative Services (10 January 2022). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, An Act to amend the Criminal Code (conversion therapy)". laws.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- Trispiotis, Ilias; Purshouse, Craig (2021). "'Conversion Therapy' As Degrading Treatment". Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. 42 (1): 104–132. doi:10.1093/ojls/gqab024. PMC 8902017. PMID 35264896.

- Purshouse, Craig; Trispiotis, Ilias (2022). "Is 'conversion therapy' tortious?". Legal Studies. 42 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1017/lst.2021.28. S2CID 236227920.

- "Conversion Therapy is Torture". International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Canady, Valerie (2015). "New report calls for an end to 'conversion therapy' for youth". The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter. 31 (12): 3–4. doi:10.1002/cbl.30088.

- Lee, Cory (2022). "A Failed Experiment: Conversion Therapy as Child Abuse". Roger Williams University Law Review. 27 (1).

- "'Conversion therapy' Can Amount to Torture and Should be Banned says UN Expert". United Nations Human Rights: Office of the High Commissioner. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- Nugraha, Ignatius Yordan (2017). "The compatibility of sexual orientation change efforts with international human rights law". Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights. 35 (3): 176–192. doi:10.1177/0924051917724654. S2CID 220052834.

- "Nothing to cure: putting an end to so-called "conversion therapies" for LGBTI people - Commissioner for Human Rights - www.coe.int". Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- "'Conversion therapies' in the EU: MEPs discuss potential ban with experts | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 17 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- "MEDIAWAN - HOMOTHERAPY, A RELIGIOUS SICKNESS (2019)". rights.mediawan.com. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- "« Homothérapies » sur Arte : le scandale des « conversions » sexuelles forcées". Le Monde.fr (in French). 26 November 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- "Health and Medical Organization Statements on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity/Expression and 'Reparative Therapy'". Lambda Legal.

- "Policy and Position Statements on Conversion Therapy". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "Memorandum of Understanding on Conversion Therapy in the UK" (PDF). United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy. December 2021.

- "Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality". American Psychological Association. 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- "Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation". Psych.org. Archived from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- APA Maintains Reparative Therapy Not Effective, Psychiatric News (news division of the American Psychiatric Association), 15 January 1999, retrieved 28 August 2007

- Luo, Michael (12 February 2007), "Some Tormented by Homosexuality Look to a Controversial Therapy", The New York Times, p. 1, retrieved 28 August 2007

- "Albania becomes third European country to ban gay 'conversion therapy'". France 24. 16 May 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

Bibliography

- Bright, Chuck (December 2004), "Deconstructing Reparative Therapy: An Examination of the Processes Involved When Attempting to Change Sexual Orientation", Clinical Social Work Journal, 32 (4): 471–481, doi:10.1007/s10615-004-0543-2, S2CID 189871877

- Cohen, Richard A. (2000). Coming Out Straight: Understanding and Healing Homosexuality. Oakhill Press. ISBN 978-1-886939-41-7.

- Cruz, David B. (July 1999). "Controlling desires: sexual orientation conversion and the limits of knowledge and law". Southern California Law Review. 72 (5): 1297–1400. hdl:10822/925326. PMID 12731502.

- Drescher, Jack (June 1998a), "I'm Your Handyman: A History of Reparative Therapies", Journal of Homosexuality, 36 (1): 19–42, doi:10.1300/J082v36n01_02, PMID 9670099

- Drescher, Jack (2001), "Ethical Concerns Raised When Patients Seek to Change Same-Sex Attractions", Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 5 (3/4): 183, doi:10.1300/j236v05n03_11, S2CID 146736819

- Drescher, Jack; Zucker, Kenneth, eds. (2006), Ex-Gay Research: Analyzing the Spitzer Study and Its Relation to Science, Religion, Politics, and Culture, New York: Harrington Park Press, ISBN 978-1-56023-557-6

- Drescher, Jack (2000). "Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man". The American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 60 (2): 191–196. doi:10.1023/a:1001968909523. PMID 10874429.

- Haldeman, Douglas (1991). "Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy for Gay Men and Lesbians: A Scientific Examination". Homosexuality: Research Implications for Public Policy. pp. 149–160. doi:10.4135/9781483325422.n10. ISBN 978-0-8039-3764-2.

- Haldeman, Douglas C. (2022). "Introduction: A history of conversion therapy, from accepted practice to condemnation". The case against conversion 'therapy': Evidence, ethics, and alternatives. pp. 3–16. doi:10.1037/0000266-001. ISBN 978-1-4338-3711-1. S2CID 243777493.

- Jones, Stanton L.; Yarhouse, Mark A. (2007). Ex-Gays?: A Longitudinal Study of Religiously Mediated Change in Sexual Orientation. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2846-3.

- Rivera, David P.; Pardo, Seth T. (2022). "Gender identity change efforts: A summary". In Haldeman, Douglas C. (ed.). The Case Against Conversion Therapy: Evidence, Ethics, and Alternatives. American Psychological Association. pp. 51–68. doi:10.1037/0000266-003. ISBN 978-1-4338-3711-1. S2CID 243776563.

- Rolls, Geoff (2019). Rolls, Geoff (ed.). Classic Case Studies in Psychology. doi:10.4324/9780429294754. ISBN 978-0-429-29475-4.

- Schmidt, Gunter (1985). "Allies and Persecutors". Journal of Homosexuality. 10 (3–4): 127–140. doi:10.1300/J082v10n03_16.

- Schwartz, Michael (25 June 2021). "Homosexuelle im modernen Deutschland: Eine Langzeitperspektive auf historische Transformationen" [Homosexuals in Modern Germany: A Long-Term Perspective on Historical Transformations]. Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (in German). 69 (3): 377–414. doi:10.1515/vfzg-2021-0028. S2CID 235689714.

- Waidzunas, Tom (2016), The Straight Line: How the Fringe Science of Ex-Gay Therapy Reoriented Sexuality, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-9615-4

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2015) [2004]. Hitler's Prisons: Legal Terror in Nazi Germany. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22829-8.

- Weindling, Paul (2015). Victims and Survivors of Nazi Human Experiments: Science and Suffering in the Holocaust. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4411-7990-6.

- Whisnant, Clayton J. (2016). Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History, 1880–1945. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-939594-10-5.

- Yoshino, Kenji (2002), "Covering", Yale Law Journal, 111 (4): 769–939, doi:10.2307/797566, hdl:20.500.13051/9392, JSTOR 797566

- Zinn, Alexander (2020b). "'Das sind Staatsfeinde' Die NS-Homosexuellenverfolgung 1933–1945" ["They are enemies of the state": The Nazi persecution of homosexuals 1933–1945] (PDF). Bulletin des Fritz Bauer Instituts (in German): 6–13. ISSN 1868-4211. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

Further reading

- Haldeman, Douglas C. (2021). Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Change Efforts: Evidence, Effects, and Ethics. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-939594-36-5.