Chemical synapse

Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow neurons to form circuits within the central nervous system. They are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They allow the nervous system to connect to and control other systems of the body.

At a chemical synapse, one neuron releases neurotransmitter molecules into a small space (the synaptic cleft) that is adjacent to another neuron. The neurotransmitters are contained within small sacs called synaptic vesicles, and are released into the synaptic cleft by exocytosis. These molecules then bind to neurotransmitter receptors on the postsynaptic cell. Finally, the neurotransmitters are cleared from the synapse through one of several potential mechanisms including enzymatic degradation or re-uptake by specific transporters either on the presynaptic cell or on some other neuroglia to terminate the action of the neurotransmitter.

The adult human brain is estimated to contain from 1014 to 5 × 1014 (100–500 trillion) synapses.[1] Every cubic millimeter of cerebral cortex contains roughly a billion (short scale, i.e. 109) of them.[2] The number of synapses in the human cerebral cortex has separately been estimated at 0.15 quadrillion (150 trillion)[3]

The word "synapse" was introduced by Sir Charles Scott Sherrington in 1897.[4] Chemical synapses are not the only type of biological synapse: electrical and immunological synapses also exist. Without a qualifier, however, "synapse" commonly refers to chemical synapses.

Structure

Synapses are functional connections between neurons, or between neurons and other types of cells.[5][6] A typical neuron gives rise to several thousand synapses, although there are some types that make far fewer.[7] Most synapses connect axons to dendrites,[8][9] but there are also other types of connections, including axon-to-cell-body,[10][11] axon-to-axon,[10][11] and dendrite-to-dendrite.[9] Synapses are generally too small to be recognizable using a light microscope except as points where the membranes of two cells appear to touch, but their cellular elements can be visualized clearly using an electron microscope.

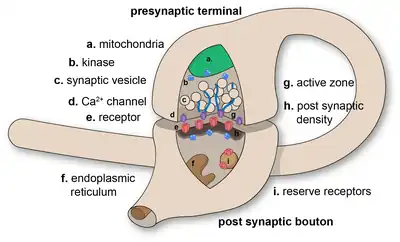

Chemical synapses pass information directionally from a presynaptic cell to a postsynaptic cell and are therefore asymmetric in structure and function. The presynaptic axon terminal, or synaptic bouton, is a specialized area within the axon of the presynaptic cell that contains neurotransmitters enclosed in small membrane-bound spheres called synaptic vesicles (as well as a number of other supporting structures and organelles, such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum). Synaptic vesicles are docked at the presynaptic plasma membrane at regions called active zones.

Immediately opposite is a region of the postsynaptic cell containing neurotransmitter receptors; for synapses between two neurons the postsynaptic region may be found on the dendrites or cell body. Immediately behind the postsynaptic membrane is an elaborate complex of interlinked proteins called the postsynaptic density (PSD).

Proteins in the PSD are involved in anchoring and trafficking neurotransmitter receptors and modulating the activity of these receptors. The receptors and PSDs are often found in specialized protrusions from the main dendritic shaft called dendritic spines.

Synapses may be described as symmetric or asymmetric. When examined under an electron microscope, asymmetric synapses are characterized by rounded vesicles in the presynaptic cell, and a prominent postsynaptic density. Asymmetric synapses are typically excitatory. Symmetric synapses in contrast have flattened or elongated vesicles, and do not contain a prominent postsynaptic density. Symmetric synapses are typically inhibitory.

The synaptic cleft—also called synaptic gap—is a gap between the pre- and postsynaptic cells that is about 20 nm (0.02 μ) wide.[12] The small volume of the cleft allows neurotransmitter concentration to be raised and lowered rapidly.[13]

An autapse is a chemical (or electrical) synapse formed when the axon of one neuron synapses with its own dendrites.

Signaling in chemical synapses

Overview

Here is a summary of the sequence of events that take place in synaptic transmission from a presynaptic neuron to a postsynaptic cell. Each step is explained in more detail below. Note that with the exception of the final step, the entire process may run only a few hundred microseconds, in the fastest synapses.[14]

- The process begins with a wave of electrochemical excitation called an action potential traveling along the membrane of the presynaptic cell, until it reaches the synapse.

- The electrical depolarization of the membrane at the synapse causes channels to open that are permeable to calcium ions.

- Calcium ions flow through the presynaptic membrane, rapidly increasing the calcium concentration in the interior.

- The high calcium concentration activates a set of calcium-sensitive proteins attached to vesicles that contain a neurotransmitter chemical.

- These proteins change shape, causing the membranes of some "docked" vesicles to fuse with the membrane of the presynaptic cell, thereby opening the vesicles and dumping their neurotransmitter contents into the synaptic cleft, the narrow space between the membranes of the pre- and postsynaptic cells.

- The neurotransmitter diffuses within the cleft. Some of it escapes, but some of it binds to chemical receptor molecules located on the membrane of the postsynaptic cell.

- The binding of neurotransmitter causes the receptor molecule to be activated in some way. Several types of activation are possible, as described in more detail below. In any case, this is the key step by which the synaptic process affects the behavior of the postsynaptic cell.

- Due to thermal vibration, the motion of atoms, vibrating about their equilibrium positions in a crystalline solid, neurotransmitter molecules eventually break loose from the receptors and drift away.

- The neurotransmitter is either reabsorbed by the presynaptic cell, and then repackaged for future release, or else it is broken down metabolically.

Neurotransmitter release

The release of a neurotransmitter is triggered by the arrival of a nerve impulse (or action potential) and occurs through an unusually rapid process of cellular secretion (exocytosis). Within the presynaptic nerve terminal, vesicles containing neurotransmitter are localized near the synaptic membrane. The arriving action potential produces an influx of calcium ions through voltage-dependent, calcium-selective ion channels at the down stroke of the action potential (tail current).[15] Calcium ions then bind to synaptotagmin proteins found within the membranes of the synaptic vesicles, allowing the vesicles to fuse with the presynaptic membrane.[16] The fusion of a vesicle is a stochastic process, leading to frequent failure of synaptic transmission at the very small synapses that are typical for the central nervous system. Large chemical synapses (e.g. the neuromuscular junction), on the other hand, have a synaptic release probability, in effect, of 1. Vesicle fusion is driven by the action of a set of proteins in the presynaptic terminal known as SNAREs. As a whole, the protein complex or structure that mediates the docking and fusion of presynaptic vesicles is called the active zone.[17] The membrane added by the fusion process is later retrieved by endocytosis and recycled for the formation of fresh neurotransmitter-filled vesicles.

An exception to the general trend of neurotransmitter release by vesicular fusion is found in the type II receptor cells of mammalian taste buds. Here the neurotransmitter ATP is released directly from the cytoplasm into the synaptic cleft via voltage gated channels.[18]

Receptor binding

Receptors on the opposite side of the synaptic gap bind neurotransmitter molecules. Receptors can respond in either of two general ways. First, the receptors may directly open ligand-gated ion channels in the postsynaptic cell membrane, causing ions to enter or exit the cell and changing the local transmembrane potential.[14] The resulting change in voltage is called a postsynaptic potential. In general, the result is excitatory in the case of depolarizing currents, and inhibitory in the case of hyperpolarizing currents. Whether a synapse is excitatory or inhibitory depends on what type(s) of ion channel conduct the postsynaptic current(s), which in turn is a function of the type of receptors and neurotransmitter employed at the synapse. The second way a receptor can affect membrane potential is by modulating the production of chemical messengers inside the postsynaptic neuron. These second messengers can then amplify the inhibitory or excitatory response to neurotransmitters.[14]

Termination

After a neurotransmitter molecule binds to a receptor molecule, it must be removed to allow for the postsynaptic membrane to continue to relay subsequent EPSPs and/or IPSPs. This removal can happen through one or more processes:

- The neurotransmitter may diffuse away due to thermally-induced oscillations of both it and the receptor, making it available to be broken down metabolically outside the neuron or to be reabsorbed.[19]

- Enzymes within the subsynaptic membrane may inactivate/metabolize the neurotransmitter.

- Reuptake pumps may actively pump the neurotransmitter back into the presynaptic axon terminal for reprocessing and re-release following a later action potential.[19]

Synaptic strength

The strength of a synapse has been defined by Bernard Katz as the product of (presynaptic) release probability pr, quantal size q (the postsynaptic response to the release of a single neurotransmitter vesicle, a 'quantum'), and n, the number of release sites. "Unitary connection" usually refers to an unknown number of individual synapses connecting a presynaptic neuron to a postsynaptic neuron. The amplitude of postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) can be as low as 0.4 mV to as high as 20 mV.[20] The amplitude of a PSP can be modulated by neuromodulators or can change as a result of previous activity. Changes in the synaptic strength can be short-term, lasting seconds to minutes, or long-term (long-term potentiation, or LTP), lasting hours. Learning and memory are believed to result from long-term changes in synaptic strength, via a mechanism known as synaptic plasticity.

Receptor desensitization

Desensitization of the postsynaptic receptors is a decrease in response to the same neurotransmitter stimulus. It means that the strength of a synapse may in effect diminish as a train of action potentials arrive in rapid succession – a phenomenon that gives rise to the so-called frequency dependence of synapses. The nervous system exploits this property for computational purposes, and can tune its synapses through such means as phosphorylation of the proteins involved.

Synaptic plasticity

Synaptic transmission can be changed by previous activity. These changes are called synaptic plasticity and may result in either a decrease in the efficacy of the synapse, called depression, or an increase in efficacy, called potentiation. These changes can either be long-term or short-term. Forms of short-term plasticity include synaptic fatigue or depression and synaptic augmentation. Forms of long-term plasticity include long-term depression and long-term potentiation. Synaptic plasticity can be either homosynaptic (occurring at a single synapse) or heterosynaptic (occurring at multiple synapses).

Homosynaptic plasticity

Homosynaptic plasticity (or also homotropic modulation) is a change in the synaptic strength that results from the history of activity at a particular synapse. This can result from changes in presynaptic calcium as well as feedback onto presynaptic receptors, i.e. a form of autocrine signaling. Homosynaptic plasticity can affect the number and replenishment rate of vesicles or it can affect the relationship between calcium and vesicle release. Homosynaptic plasticity can also be postsynaptic in nature. It can result in either an increase or decrease in synaptic strength.

One example is neurons of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which release noradrenaline, which, besides affecting postsynaptic receptors, also affects presynaptic α2-adrenergic receptors, inhibiting further release of noradrenaline.[21] This effect is utilized with clonidine to perform inhibitory effects on the SNS.

Heterosynaptic plasticity

Heterosynaptic plasticity (or also heterotropic modulation) is a change in synaptic strength that results from the activity of other neurons. Again, the plasticity can alter the number of vesicles or their replenishment rate or the relationship between calcium and vesicle release. Additionally, it could directly affect calcium influx. Heterosynaptic plasticity can also be postsynaptic in nature, affecting receptor sensitivity.

One example is again neurons of the sympathetic nervous system, which release noradrenaline, which, in addition, generates an inhibitory effect on presynaptic terminals of neurons of the parasympathetic nervous system.[21]

Integration of synaptic inputs

In general, if an excitatory synapse is strong enough, an action potential in the presynaptic neuron will trigger an action potential in the postsynaptic cell. In many cases the excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) will not reach the threshold for eliciting an action potential. When action potentials from multiple presynaptic neurons fire simultaneously, or if a single presynaptic neuron fires at a high enough frequency, the EPSPs can overlap and summate. If enough EPSPs overlap, the summated EPSP can reach the threshold for initiating an action potential. This process is known as summation, and can serve as a high pass filter for neurons.[22]

On the other hand, a presynaptic neuron releasing an inhibitory neurotransmitter, such as GABA, can cause an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) in the postsynaptic neuron, bringing the membrane potential farther away from the threshold, decreasing its excitability and making it more difficult for the neuron to initiate an action potential. If an IPSP overlaps with an EPSP, the IPSP can in many cases prevent the neuron from firing an action potential. In this way, the output of a neuron may depend on the input of many different neurons, each of which may have a different degree of influence, depending on the strength and type of synapse with that neuron. John Carew Eccles performed some of the important early experiments on synaptic integration, for which he received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1963.

Volume transmission

When a neurotransmitter is released at a synapse, it reaches its highest concentration inside the narrow space of the synaptic cleft, but some of it is certain to diffuse away before being reabsorbed or broken down. If it diffuses away, it has the potential to activate receptors that are located either at other synapses or on the membrane away from any synapse. The extrasynaptic activity of a neurotransmitter is known as volume transmission.[23] It is well established that such effects occur to some degree, but their functional importance has long been a matter of controversy.[24]

Recent work indicates that volume transmission may be the predominant mode of interaction for some special types of neurons. In the mammalian cerebral cortex, a class of neurons called neurogliaform cells can inhibit other nearby cortical neurons by releasing the neurotransmitter GABA into the extracellular space.[25] Along the same vein, GABA released from neurogliaform cells into the extracellular space also acts on surrounding astrocytes, assigning a role for volume transmission in the control of ionic and neurotransmitter homeostasis.[26] Approximately 78% of neurogliaform cell boutons do not form classical synapses. This may be the first definitive example of neurons communicating chemically where classical synapses are not present.[25]

Relationship to electrical synapses

An electrical synapse is an electrically conductive link between two abutting neurons that is formed at a narrow gap between the pre- and postsynaptic cells, known as a gap junction. At gap junctions, cells approach within about 3.5 nm of each other, rather than the 20 to 40 nm distance that separates cells at chemical synapses.[27][28] As opposed to chemical synapses, the postsynaptic potential in electrical synapses is not caused by the opening of ion channels by chemical transmitters, but rather by direct electrical coupling between both neurons. Electrical synapses are faster than chemical synapses.[13] Electrical synapses are found throughout the nervous system, including in the retina, the reticular nucleus of the thalamus, the neocortex, and in the hippocampus.[29] While chemical synapses are found between both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, electrical synapses are most commonly found between smaller local inhibitory neurons. Electrical synapses can exist between two axons, two dendrites, or between an axon and a dendrite.[30][31] In some fish and amphibians, electrical synapses can be found within the same terminal of a chemical synapse, as in Mauthner cells.[32]

Effects of drugs

One of the most important features of chemical synapses is that they are the site of action for the majority of psychoactive drugs. Synapses are affected by drugs, such as curare, strychnine, cocaine, morphine, alcohol, LSD, and countless others. These drugs have different effects on synaptic function, and often are restricted to synapses that use a specific neurotransmitter. For example, curare is a poison that stops acetylcholine from depolarizing the postsynaptic membrane, causing paralysis. Strychnine blocks the inhibitory effects of the neurotransmitter glycine, which causes the body to pick up and react to weaker and previously ignored stimuli, resulting in uncontrollable muscle spasms. Morphine acts on synapses that use endorphin neurotransmitters, and alcohol increases the inhibitory effects of the neurotransmitter GABA. LSD interferes with synapses that use the neurotransmitter serotonin. Cocaine blocks reuptake of dopamine and therefore increases its effects.

History and etymology

During the 1950s, Bernard Katz and Paul Fatt observed spontaneous miniature synaptic currents at the frog neuromuscular junction.[33] Based on these observations, they developed the 'quantal hypothesis' that is the basis for our current understanding of neurotransmitter release as exocytosis and for which Katz received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970.[34] In the late 1960s, Ricardo Miledi and Katz advanced the hypothesis that depolarization-induced influx of calcium ions triggers exocytosis.

Sir Charles Scott Sherringtonin coined the word 'synapse' and the history of the word was given by Sherrington in a letter he wrote to John Fulton:

'I felt the need of some name to call the junction between nerve-cell and nerve-cell... I suggested using "syndesm"... He [ Sir Michael Foster ] consulted his Trinity friend Verrall, the Euripidean scholar, about it, and Verrall suggested "synapse" (from the Greek "clasp").'–Charles Scott Sherrington[4]

Notes

- Drachman D (2005). "Do we have brain to spare?". Neurology. 64 (12): 2004–5. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000166914.38327.BB. PMID 15985565. S2CID 38482114.

- Alonso-Nanclares L, Gonzalez-Soriano J, Rodriguez JR, DeFelipe J (September 2008). "Gender differences in human cortical synaptic density". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (38): 14615–9. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10514615A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803652105. PMC 2567215. PMID 18779570.

- Brain Facts and Figures Washington University.

- Cowan, W. Maxwell; Südhof, Thomas C.; Stevens, Charles F. (2003). Synapses. JHU Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780801871184. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Rapport, Richard L. (2005). Nerve Endings: The Discovery of the Synapse. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 1–37. ISBN 978-0-393-06019-5.

- Squire, Larry R.; Floyd Bloom; Nicholas Spitzer (2008). Fundamental Neuroscience. Academic Press. pp. 425–6. ISBN 978-0-12-374019-9.

- Hyman, Steven E.; Eric Jonathan Nestler (1993). The Molecular Foundations of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 425–6. ISBN 978-0-88048-353-7.

- Smilkstein, Rita (2003). We're Born to Learn: Using the Brain's Natural Learning Process to Create Today's Curriculum. Corwin Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7619-4642-7.

- Lytton, William W. (2002). From Computer to Brain: Foundations of Computational Neuroscience. Springer. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-387-95526-1. Axons connecting dendrite to dendrite are dendrodendritic synapses. Axons which connect axon to dendrite are called axodendritic synapses

-

Garber, Steven D. (2002). Biology: A Self-Teaching Guide. John Wiley and Sons. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-471-22330-6.

synapses connect axons to cell body.

- Weiss, Mirin; Dr Steven M. Mirin; Dr Roxanne Bartel (1994). Cocaine. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-58562-138-5. Retrieved 2008-12-26. Axons terminating on the postsynaptic cell body are axosomatic synapses. Axons that terminate on axons are axoaxonic synapses

- Widrow, Bernard; Kim, Youngsik; Park, Dookun; Perin, Jose Krause (2019). "Nature's Learning Rule". Artificial Intelligence in the Age of Neural Networks and Brain Computing. Elsevier. pp. 1–30. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815480-9.00001-3. ISBN 978-0-12-815480-9. S2CID 125516633.

- Kandel, Schwartz & Jessell 2000, p. 182

- Bear, Mark F; Connors, Barry W; Paradiso, Michael A (2007). Neuroscience: exploring the brain. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 113–118.

- Llinás R, Steinberg IZ, Walton K (1981). "Relationship between presynaptic calcium current and postsynaptic potential in squid giant synapse". Biophysical Journal. 33 (3): 323–351. Bibcode:1981BpJ....33..323L. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84899-0. PMC 1327434. PMID 6261850.

- Chapman, Edwin R. (2002). "Synaptotagmin: A Ca2+ sensor that triggers exocytosis?". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 3 (7): 498–508. doi:10.1038/nrm855. ISSN 1471-0080. PMID 12094216. S2CID 12384262.

- Craig C. Garner and Kang Shen. Structure and Function of Vertebrate and Invertebrate Active Zones. Structure and Functional Organization of the Synapse. Ed: Johannes Hell and Michael Ehlers. Springer, 2008.

- Romanov, Roman A.; Lasher, Robert S.; High, Brigit; Savidge, Logan E.; Lawson, Adam; Rogachevskaja, Olga A.; Zhao, Haitian; Rogachevsky, Vadim V.; Bystrova, Marina F.; Churbanov, Gleb D.; Adameyko, Igor; Harkany, Tibor; Yang, Ruibiao; Kidd, Grahame J.; Marambaud, Philippe; Kinnamon, John C.; Kolesnikov, Stanislav S.; Finger, Thomas E. (2018). "Chemical synapses without synaptic vesicles: Purinergic neurotransmission through a CALHM1 channel-mitochondrial signaling complex". Science Signaling. 11 (529): eaao1815. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aao1815. ISSN 1945-0877. PMC 5966022. PMID 29739879.

- Sherwood L., stikawy (2007). Human Physiology 6e: From Cells to Systems

- Díaz-Ríos M, Miller MW (June 2006). "Target-specific regulation of synaptic efficacy in the feeding central pattern generator of Aplysia: potential substrates for behavioral plasticity?". Biol. Bull. 210 (3): 215–29. doi:10.2307/4134559. JSTOR 4134559. PMID 16801496. S2CID 34154835.

- Rang, H.P.; Dale, M.M.; Ritter, J.M. (2003). Pharmacology (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4.

- Bruce Alberts; Alexander Johnson; Julian Lewis; Martin Raff; Keith Roberts; Peter Walter, eds. (2002). "Ch. 11. Section: Single Neurons Are Complex Computation Devices". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- Zoli M, Torri C, Ferrari R, et al. (1998). "The emergence of the volume transmission concept". Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 26 (2–3): 136–47. doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00048-9. PMID 9651506. S2CID 20495134.

- Fuxe K, Dahlström A, Höistad M, et al. (2007). "From the Golgi-Cajal mapping to the transmitter-based characterization of the neuronal networks leading to two modes of brain communication: wiring and volume transmission" (PDF). Brain Res Rev. 55 (1): 17–54. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.02.009. hdl:10447/9980. PMID 17433836. S2CID 1323780.

- Oláh S, Füle M, Komlósi G, et al. (2009). "Regulation of cortical microcircuits by unitary GABA-mediated volume transmission". Nature. 461 (7268): 1278–81. Bibcode:2009Natur.461.1278O. doi:10.1038/nature08503. PMC 2771344. PMID 19865171.

- Rózsa M, Baka J, Bordé S, Rózsa B, Katona G, Tamás G, et al. (2015). "Unitary GABAergic volume transmission from individual interneurons to astrocytes in the cerebral cortex" (PDF). Brain Structure and Function. 222 (1): 651–659. doi:10.1007/s00429-015-1166-9. PMID 26683686. S2CID 30728927.

- Kandel, Schwartz & Jessell 2000, p. 176

- Hormuzdi et al. 2004

- Connors BW, Long MA (2004). "Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain". Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27 (1): 393–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131128. PMID 15217338.

- Veruki ML, Hartveit E (December 2002). "Electrical synapses mediate signal transmission in the rod pathway of the mammalian retina". J. Neurosci. 22 (24): 10558–66. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10558.2002. PMC 6758447. PMID 12486148.

- Bennett MV, Pappas GD, Aljure E, Nakajima Y (March 1967). "Physiology and ultrastructure of electrotonic junctions. II. Spinal and medullary electromotor nuclei in mormyrid fish". J. Neurophysiol. 30 (2): 180–208. doi:10.1152/jn.1967.30.2.180. PMID 4167209.

- Pereda AE, Rash JE, Nagy JI, Bennett MV (December 2004). "Dynamics of electrical transmission at club endings on the Mauthner cells". Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 47 (1–3): 227–44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.662.9352. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.06.010. PMID 15572174. S2CID 9527518.

- Augustine, George J.; Kasai, Haruo (2007-02-01). "Bernard Katz, quantal transmitter release and the foundations of presynaptic physiology". The Journal of Physiology. 578 (Pt 3): 623–625. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123224. PMC 2151334. PMID 17068096.

- "Nobel prize". British Medical Journal. 4 (5729): 190. 1970-10-24. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5729.190. PMC 1819734. PMID 4320287.

References

- Carlson, Neil R. (2007). Physiology of Behavior (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-205-59389-7.

- Kandel, Eric R.; Schwartz, James H.; Jessell, Thomas M. (2000). Principles of Neural Science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-7701-1.

- Llinás R, Sugimori M, Simon SM (April 1982). "Transmission by presynaptic spike-like depolarization in the squid giant synapse". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79 (7): 2415–9. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.2415L. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.7.2415. PMC 346205. PMID 6954549.

- Llinás R, Steinberg IZ, Walton K (1981). "Relationship between presynaptic calcium current and postsynaptic potential in squid giant synapse". Biophysical Journal. 33 (3): 323–352. Bibcode:1981BpJ....33..323L. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84899-0. PMC 1327434. PMID 6261850.

- Bear, Mark F.; Connors, Barry W.; Paradiso, Michael A. (2001). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-3944-3.

- Hormuzdi, SG; Filippov, MA; Mitropoulou, G; Monyer, H; Bruzzone, R (March 2004). "Electrical synapses: a dynamic signaling system that shapes the activity of neuronal networks". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1662 (1–2): 113–137. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.023. PMID 15033583.

- Karp, Gerald (2005). Cell and Molecular Biology: concepts and experiments (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-46580-5.

- Nicholls, J.G.; Martin, A.R.; Wallace, B.G.; Fuchs, P.A. (2001). From Neuron to Brain (4th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-439-3.

External links

- Synapse Review for Kids

- Synapse – Cell Centered Database

- Atlas of Ultrastructure Neurocytology An electron microscope picture gallery assembled by Kristen Harris' lab of synapses and other neuronal structures.