Population history of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

Population figures for the Indigenous peoples of the Americas prior to European colonization have been difficult to establish. By the end of the 20th century, most scholars gravitated toward an estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more.[1][2]

In an effort to circumvent the hold which the Ottoman Empire held on the overland trade routes to East Asia and the hold that the Aeterni regis granted to Portugal on maritime routes via the African coast and the Indian Ocean, the monarchs of the nascent Spanish Empire decided to fund Columbus' voyage in 1492, which eventually led to the establishment of settler-colonial states and the migration of millions of Europeans to the Americas. The population of African and European peoples in the Americas grew steadily, starting in 1492, and at the same time, the Indigenous population began to plummet. Eurasian diseases such as influenza, pneumonic plagues, and smallpox, in combination with conflict, forced removal, enslavement, imprisonment, and outright warfare with European newcomers reduced populations and disrupted traditional societies.[3][4] The causes of the decline and the extent of it have been characterized as a genocide by some scholars[5][6][7] while other scholars have disputed this characterization.[6][8][9]

Population overview

Pre-Columbian population figures are difficult to estimate due to the fragmentary nature of the evidence. Estimates range from 8–112 million.[10] Scholars have varied widely on the estimated size of the Indigenous populations prior to colonization and on the effects of European contact.[11] Estimates are made by extrapolations from small bits of data. In 1976, geographer William Denevan used the existing estimates to derive a "consensus count" of about 54 million people. Nonetheless, more recent estimates still range widely.[12] In 1992, Denevan suggested that the total population was approximately 53.9 million and the populations by region were, approximately, 3.8 million for the United States and Canada, 17.2 million for Mexico, 5.6 million for Central America, 3 million for the Caribbean, 15.7 million for the Andes and 8.6 million for lowland South America.[13] A 2020 genetic study suggests that prior estimates for the pre-Columbian Caribbean population may have been at least tenfold too large.[14] Historian David Stannard estimates that the extermination of Indigenous peoples took the lives of 100 million people: "...the total extermination of many American Indian peoples and the near-extermination of others, in numbers that eventually totaled close to 100,000,000."[15] A 2019 study estimates the pre-Columbian Indigenous population contained more than 60 million people, but dropped to 6 million by 1600, based on a drop in atmospheric CO2 during that period.[16][17] Other studies have disputed this conclusion.[18][19]

The Indigenous population of the Americas in 1492 was not necessarily at a high point and may actually have already been in decline in some areas. Indigenous populations in most areas of the Americas reached a low point by the early 20th century.[20]

Using an estimate of approximately 37 million people in Mexico, Central and South America in 1492 (including 6 million in the Aztec Empire, 5–10 million in the Mayan States, 11 million in what is now Brazil, and 12 million in the Inca Empire), the lowest estimates give a death toll from all causes of 80% by the end of the 17th century (nine million people in 1650).[21] Latin America would match its 15th-century population early in the 19th century; it numbered 17 million in 1800, 30 million in 1850, 61 million in 1900, 105 million in 1930, 218 million in 1960, 361 million in 1980, and 563 million in 2005.[21] In the last three decades of the 16th century, the population of present-day Mexico dropped to about one million people.[21] The Maya population is today estimated at six million, which is about the same as at the end of the 15th century, according to some estimates.[21] In what is now Brazil, the Indigenous population declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated four million to some 300,000. Over 60 million Brazilians possess at least one Native South American ancestor, according to a DNA study.[22]

While it is difficult to determine exactly how many Natives lived in North America before Columbus,[23] estimates range from 3.8 million, as mentioned above, to 7 million[24] people to a high of 18 million.[25] Scholars vary on the estimated size of the Indigenous population in what is now Canada prior to colonization and on the effects of European contact.[26] During the late 15th century is estimated to have been between 200,000[27] and two million,[28] with a figure of 500,000 currently accepted by Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Health.[29] Although not without conflict, European Canadians' early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful.[30] However repeated outbreaks of European infectious diseases such as influenza, measles and smallpox (to which they had no natural immunity),[31] combined with other effects of European contact, resulted in a twenty-five percent to eighty percent Indigenous population decrease post-contact.[27] Roland G Robertson suggests that during the late 1630s, smallpox killed over half of the Wyandot (Huron), who controlled most of the early North American fur trade in the area of New France.[32] In 1871 there was an enumeration of the Indigenous population within the limits of Canada at the time, showing a total of only 102,358 individuals.[33] From 2006 to 2016, the Indigenous population has grown by 42.5 percent, four times the national rate.[34] According to the 2011 Canadian Census, Indigenous peoples (First Nations – 851,560, Inuit – 59,445 and Métis – 451,795) numbered at 1,400,685, or 4.3% of the country's total population.[35]

The population debate has often had ideological underpinnings.[36] Low estimates were sometimes reflective of European notions of cultural and racial superiority. Historian Francis Jennings argued, "Scholarly wisdom long held that Indians were so inferior in mind and works that they could not possibly have created or sustained large populations."[37] In 1998, Africanist Historian David Henige said many population estimates are the result of arbitrary formulas applied from unreliable sources.[38]

Estimations

| Author | Date | USA and Canada | Mexico | Mesoamerica | Caribbean | Andes | Patagonia and Amazonia |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sapper[39] | 1924 | 2 million-3 million | 12 million-15 million | 5 million-6 million | 3 million-4 million | 12 million-15 million | 3 million-5 million | 37 million-48.5 million |

| Kroeber[40] | 1939 | 0.9 million | 3.2 million | 0.1 million | 0.2 million | 3 million | 1 million | 8.4 million |

| Steward[41] | 1949 | 1 million | 4.5 million | 0.74 million | 0.22 million | 6.13 million | 2.9 million | 15.49 million |

| Rosenblat[42] | 1954 | 1 million | 4.5 million | 0.8 million | 0.3 million | 4.75 million | 2.03 million | 13.38 million |

| Dobyns[43] | 1966 | 9.8-12.25 million | 30-37.5 million | 10.8-13.5 million | 0.44-0.55 million | 30-37.5 million | 9-11.25 million | 90.04-112.55 million |

| Ubelaker[44] | 1988 | 1.213-2.639 million | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Denevan[45] | 1992 | 3.79 million | 17.174 million | 5.625 million | 3 million | 15.696 million | 8.619 million | 53.904 million |

| Snow[46] | 2001 | 3.44 million | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Alchon[47] | 2003 | 3.5 million | 16 million-18 million | 5 million-6 million | 2 million-3 million | 13 million-15 million | 7 million-8 million | 46.5 million-53.5 million |

| Thornton[48] | 2005 | 7 million | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Estimations by tribe

Population size for Native American tribes is difficult to state definitively, but at least one writer has made estimates, often based on an assumed proportion of the number of warriors to total population for the tribe.[49] Typical proportions were 5 people per one warrior and at least 1 up to 5 warriors (therefore at least 5-25 people) per lodge, cabin or house.

| Rank | Cultural Area | Region | Tribe or nation | Highest pop. estimate | Year | Towns/ villages |

Lodges/cabins/houses/tents/tipis etc. | Sources of estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Sioux [Note 1][50][51] | 150,000 - 50,000 (1841) | 1762 | 40+ | 5,000+ lodges (in 1846) | Lt. James Gorrell and A. Ramsey |

| 2 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Choctaw [Note 2][52] | 125,000 | 1718 | 70+ | Le Page du Pratz | |

| 3 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Illinois [Note 3][53] | 100,000 | 1658 | 60 | Jean de Quen | |

| 4a | Great Basin | Mexican Cession | Shoshone | 60,000 | 1822 | (number without 20,000 East Shoshone) | Jeddediah Morse | |

| 4b | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Eastern Shoshone | 20,000 | 1822 | Jeddediah Morse | ||

| 5 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Tigua | 78,100+ | 1626 | 20 | 7,000 houses only in two largest pueblos | Alonso de Benavides[54] |

| 6 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Blackfoot [Note 4][55] | 75,000 - 60,000 (1841) | 1836 | (60,000 in 1841 & approx. 75,000 in 1836) | George Catlin | |

| 7 | NE Woodlands | Middle Colonies | Iroquois [Note 5][56] | 70,000 | 1690 | 226 | (nearly 60 towns destroyed in 1779–80) | A. L. Lahontan and J. R. Swanton |

| 8 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Apache | 60,000 | 1700 | José de Urrutia | ||

| 9 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Creek (Muscogee) | 50,000 | 1794 | 100 | (at least 100 towns in 1789 per Henry Knox) | R. Brooke Roberts & Henry Knox |

| 10 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Hopi [Note 6][57] | 50,000 | 1584 | 7 | Antonio de Espejo | |

| 11 | NE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Shawnee | 50,000 - 15,000 (1702) | 1540 | 38+ | (at first contact est. 50,000 & 15,000 in 1702) | M. A. Jaimes[58] & Pierre d'Iberville |

| 12 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Crows (Absaroka) | 45,000 | 1834 | Samuel Gardner Drake[59][60] | ||

| 13 | NE Woodlands | Canada Ontario | Hurons [Note 7][61] | 40,000 | 1632 | 32 | Gabriel Sagard and J. Lalemant | |

| 14 | Great Plains | Texas Annexation | Comanche | 40,000 | 1832 | George Catlin | ||

| 15 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Tano/Maguas | 40,000 | 1584 | 11 | Antonio de Espejo | |

| 16 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Miami [Note 8][62] | 40,000 | 1657 | 20+ | (one of their towns had 400 families in 1751) | Gabriel Druillettes |

| 17 | NE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Ioways | 40,000 | 1762 | 16+ | (at least 16 towns in the early 19th century) | Lt. James Gorrell |

| 18 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Piegan | 40,000 | 1700s | 8,000 lodges | George Bird Grinnell | |

| 19 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Pawnee [Note 9][63] | 38,000 | 1719 | 38 | 5,000 - 6,000 cabins/lodges & 7,600 warriors | Claude Du Tisne and L. Krzywicki |

| 20 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Chippewa (Ojibwe) | 36,000 | 1860 | (30,000 Chippewa & 6,000 Ojibwe in 1860) | Emmanuel Domenech[64] | |

| 21 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Assiniboine | 35,000 | 1823 | 30+ | 3,000 lodges (in 1823) | W. H. Keating and G. C. Beltrami |

| 22 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Apalachee | 34,000 | 1635 | 11+ | J. R. Swanton | |

| 23 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Navajo | 30,000 | 1626 | Alonso de Benavides | ||

| 24 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Cherokee [Note 10][65] | 30,000 | 1730-1735 | 65+ | J. Adair | |

| 25 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Tuscarora [Note 11][66] | 30,000 | 1600 | 24 | D. Cusick | |

| 26 | NE Woodlands | New England | Narragansett | 30,000 | 1642 | 8+ | S. G. Drake and J. R. Swanton | |

| 27 | NE Woodlands | New England | Mohicans | 30,000 | 1600 | 16+ | J. A. Maurault and J. R. Swanton | |

| 28 | NE Woodlands | New England | Massachusett | 30,000 | 1600 | J. A. Maurault | ||

| 29 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Jemez [Note 12][67] | 30,000 | 1584 | 11 | Antonio de Espejo | |

| 30 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Timucua | 30,000 | 1635 | 141 | 44 missions in 1635: 30,000 Christian Indians | J. R. Swanton |

| 31 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Clayoquot | 30,000 | 1780s | (30,000 under the rule of chief Wickaninnish) | Ho. Doc. 1839-1840 and Meares | |

| 32a | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Sask. | Woods Cree in Sask. | 5,600 | 1670 | James Mooney | ||

| 32b | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Manitoba | Cree living in Manitoba | 4,250 | 1670 | James Mooney | ||

| 32c | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Alberta | Woodland Cree in Alberta | 3,050 | 1670 | James Mooney | ||

| 32d | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Ontario | Swampy Cree in Ontario | 2,100 | 1670 | James Mooney | ||

| 32e | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Ontario | Moose Cree in Ontario | 5,000 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 32f | Great Plains | Canada | Plains Cree (Alb., Sask.) | 7,000 | 1853 | David G. Mandelbaum | ||

| 33a | Great Basin | Mexican Cession | Ute living in Utah | 13,050 | 1867 | Indian Affairs 1867 | ||

| 33b | Great Basin | Mexican Cession | Ute living in Colorado | 7,000 | 1866 | Indian Affairs 1866 | ||

| 33c | Great Basin | Mexican Cession | Ute living in New Mexico | 6,000 | 1846 | H. H. Davis | ||

| 34 | Northwest Coast | Oregon Country | Chinook | 22,000 | 1780 | 1,000 lodges just among the Lower Chinook | James Mooney and Duflot de Mofras | |

| 35 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Foxes & Mascouten | 20,000+ | 1679 | Claude Dablon | ||

| 36 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Chickasaw | 20,000 | 1687 | 27+ | Louis Hennepin | |

| 37 | NE Woodlands | Canada Ontario | Neutrals [Note 13][68] | 20,000 | 1616 | 40 | Samuel de Champlain | |

| 38 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Zuni | 20,000 | 1584 | Antonio de Espejo | ||

| 39 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Tewa/Ubates | 20,000 | 1584 | 5 | Antonio de Espejo | |

| 40 | NE Woodlands | New England | Pequots [Note 14][69] | 20,000 | 1600s | 21 | Daniel Gookin and J. R. Swanton | |

| 41 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Skidi | 20,000+ | 1700s | 22 | 4,400 cabins (on average 200 per town) | George Bird Grinnell |

| 42 | SE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Natchez | 20,000 | 1715 | 60 | Pierre Charlevoix | |

| 43 | NE Woodlands | Middle Colonies | Lenape (exonym Delaware) | 18,400 | 1635-1648 | 118 | (3,680 warriors in 27 divisions or "kingdoms") | R. Evelin, Th. Donaldson & Swanton |

| 44 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Mandan | 17,500 - 15,000 (1836) | 1738 | 17 | 1,000+ lodges and 3,500 warriors | W. Sanstead[70] & Indian Affairs 1836 |

| 45 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Atsina | 16,800 | 1837 | (smallpox killed about 1/2 in 1838) | Indian Affairs 1837 | |

| 46 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Powhatan | 16,600 | 1616 | 161 | (3,320 warriors in 1616) | William Strachey and John Smith |

| 47 | NE Woodlands | Middle Colonies | Nanticoke confederacy | 16,500 | 1600 | 16+ | (1,100 warriors in 4 tribes, in total 12 tribes) | John Smith and J. R. Swanton |

| 48 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Arikaras | 16,000 | 1700s | 48 | Kinglsey M. Bray[71] | |

| 49 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Vancouver Island Salish | 15,500 | 1780 | (Coast Salish on Vancouver Island) | Herbert C. Taylor | |

| 50 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Arapaho | 15,250 | 1812 | M. R. Stuart | ||

| 51 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Wichita | 15,000+ | 1772 | (3,000+ warriors) | Juan de Ripperda | |

| 52 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Keres [Note 15][72] | 15,000 | 1584 | 7 | Antonio de Espejo | |

| 53 | NE Woodlands | Canada Acadia | Abenaki | 15,000 | 1600 | 31 | J. A. Maurault and J. R. Swanton | |

| 54 | NE Woodlands | New England | Pennacook | 15,000 | 1674 | Daniel Gookin | ||

| 55 | NE Woodlands | New England | Wampanoag | 15,000 | 1600s | 46 | Daniel Gookin and J. R. Swanton | |

| 56 | NE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Missouria [Note 16][73] | 15,000 | 1764 | H. Bouquet and J. Buchanan | ||

| 57 | NE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Osage | 15,000 | 1702 | 17 | 1,500 families | Pierre d'Iberville |

| 58 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Hidatsa | 15,000 | 1835 | William M. Denevan[74] | ||

| 59 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Ottawa | 15,000 - 13,150 (1825) | 1777 | (3,000 warriors in 1777) | L. Houck and J. C. Colhoun | |

| 60 | Southwest | Texas Annexation | Coahuiltecan Tribes | 15,000 | 1690 | James Mooney | ||

| 61 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Mishinimaki | 15,000 | 1600s | 30 | Claude Dablon | |

| 62 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Erie | 14,500 | 1653 | J. N. B. Hewitt | ||

| 63 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Kwakiutl | 14,500 | 1780 | Herbert C. Taylor | ||

| 64 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Nootka | 14,000 | 1780 | Herbert C. Taylor | ||

| 65 | NE Woodlands | New England | Wappinger | 13,500 | 1600 | 68 | E. J. Boesch and J. R. Swanton | |

| 66 | NE Woodlands | Canada Ontario | Mississaugas | 12,000+ | 1744 | 3+ | (2,400 warriors in 3 large towns) | Arthur Dobbs |

| 67 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Coast Salish (except VI) | 12,000 | 1835 | (Coast Salish except Vancouver Island) | Wilson Duff | |

| 68 | Northwest Coast | Oregon Country | Puget Sound Salish | 10,300 | 1780 | Herbert C. Taylor | ||

| 69 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Catawba | 10,000 | 1700 | R. Mills and H. Lewis Scaife[75] | ||

| 70 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pima | 10,000 | 1850 | S. Mowry | ||

| 71 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Cheyenne | 10,000 | 1856 | 1,000 lodges and 2,000 warriors | Thomas S. Twiss | |

| 72 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Chilkat | 10,000 | 1869 | F. K. Louthan | ||

| 73 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Tompiro | 10,000 | 1626 | 15 | Alonso de Benavides | |

| 74 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Menominee | 10,000 | 1778 | (2,000 warriors) | H. R. Schoolcraft | |

| 75 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Mohave | 10,000 | 1869 | William Abraham Bell | ||

| 76 | Southwest | Texas Annexation | Jumanos | 10,000 | 1584 | 5+ | 5 large pueblos | Antonio de Espejo |

| 77 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Seminole | 10,000 | 1836 | 37 | (other figures: 4,883 in 1821 / 6,385 in 1822) | N. G. Taylor and Capt. Hugh Young |

| 78 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Calusa | 10,000 | 1570 | 56 | Lopez de Velasco & J. R. Swanton | |

| 79 | Great Plains | Texas Annexation | Kichai, Waco, Tawakoni | 10,000 | 1719 | (2,000 warriors) | Benard de La Harpe | |

| 80 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Flathead Salish | 9,000 | 1821 | (1,800 warriors) | M. R. Stuart | |

| 81 | Great Basin | Oregon Country | Bannock and Diggers | 9,000 | 1848 | 1,200 lodges of southern Bannock (in 1829) | Joseph L. Meek and Jim Bridger | |

| 82 | SE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Caddo | 8,500 | 1690 | James Mooney | ||

| 83 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Haida (except Kaigani) | 8,400 | 1787 | 42 | C. F. Newcombe | |

| 84 | Great Basin | Mexican Cession | Paiute | 8,200 | 1859 | John Weiss Forney | ||

| 85 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Kansa | 8,000 | 1764 | (1,600 warriors) | Henry Bouquet | |

| 86 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Nez Perce | 8,000 | 1806 | Isaac Ingalls Stevens | ||

| 87 | NE Woodlands | Canada Ontario | Tionontati (Petun) | 8,000 | 1600 | 9 | 9 towns, 600 families in the main town | James Mooney & Jes. Rel. XXXV |

| 88 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Chipewyan | 7,500 | 1812 | Samuel Gardner Drake | ||

| 89 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Shuswap | 7,200 | 1850 | James Teit and A. C. Anderson | ||

| 90 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Omaha-Ponca | 7,200 | 1702 | Pierre d'Iberville | ||

| 91 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Yamasee | 7,000 | 1702 | 10 | (1,400 warriors) | Guillaume Delisle |

| 92 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Conoy | 7,000+ | 1600 | 13+ | W. M. Denevan[74] & J. R. Swanton | |

| 93 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Tsimshian | 7,000 | 1780 | James Mooney | ||

| 94 | Northwest Coast | Oregon Country | Umpqua | 7,000 | 1835 | Samuel Parker | ||

| 95 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Papago | 6,800 | 1863 | 19 | Indian Affairs 1863 | |

| 96 | NE Woodlands | Canada Quebec | Algonquin (Anicinàpe) | 6,500 | 1860 | Emmanuel Domenech | ||

| 97 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Sauk | 6,500 | 1786 | Wisconsin Hist. Coll., XII | ||

| 98 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Potawatomi | 6,500 | 1829 | Peter Buell Porter & William Clark | ||

| 99 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Piro | 6,000 | 1626 | 14 | Alonso de Benavides | |

| 100 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Pueblo Acoma | 6,000 | 1584 | 500+ houses | Antonio de Espejo | |

| 101 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Wea | 6,000 | 1718 | 5 | (1,200 warriors) | N. Y. Col. Dcts., IX |

| 102 | SE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Quapaw | 6,000 | 1541 | 4+ | Fidalgo D'Elvas | |

| 103 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Yakima | 6,000 | 1857 | (1,200 warriors) | A. N. Armstrong | |

| 104 | NE Woodlands | Middle Colonies | Montauk | 6,000 | 1600 | 20 | J. R. Swanton | |

| 105 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Winnebago | 5,800 | 1818 | Jeddediah Morse | ||

| 106 | Northwest Coast | Oregon Country | Rogue River Indians | 5,600 | 1780 | James Mooney | ||

| 107 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Kutenai (Ktunaxa) | 5,600 | 1820 | Jeddediah Morse | ||

| 108 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Yuma | 5,500 | 1775-1855 | A. F. Bandelier, Ten Kate | ||

| 109 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Innu and Naskapi | 5,500 | 1600 | 17+ | James Mooney and J. R. Swanton | |

| 110 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Kiowa | 5,450 | 1805-1807 | Z. M. Pike | ||

| 111 | NE Woodlands | Middle Colonies | Susquehanna | 5,000 | 1600 | 20+ | James Mooney and J. R. Swanton | |

| 112 | NE Woodlands | New England | Pocumtuk | 5,000 | 1600 | Pocumtuc History | ||

| 113 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Thompson (Nlaka'pamux) | 5,000 | 1858 | James Teit & A. C. Anderson | ||

| 114 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Carrier (Dakelh) | 5,000 | 1780 | James Mooney and A. C. Anderson | ||

| 115 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Klikitat | 5,000 | 1829 | (1,000 warriors under chief Casanow) | Paul Kane | |

| 116 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Yuchi | 5,000 - 2,500 (in 1777) | 1550 | (at least 500 warriors in year 1777) | William Bartram & carolana.com | |

| 117 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Chilcotin | 4,600 | 1793 | (by 1888 population was 10% of 1793 level) | A. G. Morice and HBC employees | |

| 118 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Chopunnish | 4,300 | 1806 | aaanativearts.com/extinct-tribes | ||

| 119 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Honniasont | 4,000+ | 1662 | (800+ warriors) | J. R. Swanton[76] | |

| 120 | NE Woodlands | New England | Niantic | 4,000 | 1500 | Capers Jones[77] | ||

| 121 | SE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Chitimacha | 4,000 | 1699 | 300+ cabins and 800 warriors | Benard de La Harpe | |

| 122 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Lillooet (Stʼatʼimc) | 4,000 | 1780 | James Mooney and James Teit | ||

| 123 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Modoc & Klamath | 4,000 | 1868 | Indian Affairs 1868 | ||

| 124 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Weapemeoc | 4,000 | 1585 | 5+ | (800 warriors) | S. R. Grenville |

| 125 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Chowanoc | 3,500+ | 1585 | 5 | (1585: 700 warriors just in one of five towns) | carolana.com |

| 126 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Acolapissa | 3,500 | 1600 | 120+ cabins | Acolapissa History | |

| 127 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Colville | 3,500 | 1806 | Isaac Ingalls Stevens | ||

| 128 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Babine (Witsuwitʼen) | 3,500 | 1780 | James Mooney | ||

| 129 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Havasupai & Tontos | 3,500 | 1854 | Amiel Weeks Whipple | ||

| 130 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Kiowa-Apache | 3,375 | 1818 | Jeddediah Morse | ||

| 131 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Kutchin | 3,200 | 1740-1857 | (six subdivisions, in total 640 warriors) | Richardson, A. G. Morice, Krzywicki | |

| 132 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada B.C. | Sekani | 3,200 | 1780 | James Mooney | ||

| 133 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada N.L. | Beothuk | 3,050 | 1497 | Ralph T. Pastore, Leslie Upton[78] | ||

| 134 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Alibamu | 3,000 | 1764 | 6 | (600 warriors) | Henry Bouquet |

| 135 | NE Woodlands | New England | Nantucket | 3,000 | 1660 | J. Barber in J. Chase | ||

| 136 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Nottoway | 3,000 | 1586 | (600 warriors) | R. Lane in Hakluyt, VIII | |

| 137 | SE Woodlands | Texas Annexation | Tonkawa | 3,000 | 1814 | (600 warriors) | John F. Schermerhorn | |

| 138 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Wallawalla | 3,000 | 1848 | Miss A. J. Allen | ||

| 139 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Spokan | 3,000 | 1848 | Joseph L. Meek | ||

| 140 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Okinagan | 3,000 | 1780 | James Teit | ||

| 141 | NE Woodlands | Canada Ontario | Nipissing | 3,000 | 1764 | (600 warriors) | Th. Hutchins in H. R. Schoolcraft | |

| 142 | NE Woodlands | New England | Shawomets & Cowsetts | 3,000 | 1500 | Capers Jones[77] | ||

| 143 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Bellabella: Heiltsuk/Haisla | 2,700 | 1780 | James Mooney | ||

| 144 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Nahani and Tahltan | 2,650 | 1780 | (includes 300 Esbataottine) | James Mooney | |

| 145 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Skitswish | 2,600 | 1806 | Isaac Ingalls Stevens | ||

| 146 | NE Woodlands | New England | Mohegan | 2,500+ | 1680 | 21 | (500+ warriors) | Mass. Hist. Coll. and J. R. Swanton |

| 147 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Clackamas | 2,500 | 1780 | 11 | James Mooney | |

| 148 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Yavapai | 2,500 | 1869 | J. Ross Browne | ||

| 149 | NE Woodlands | New England | Nipmuc | 2,500 | 1500 | 29 | Capers Jones[77] and J. R. Swanton | |

| 150 | Southwest | Texas Annexation | Karankawa | 2,500+ | 1751 | (500+ warriors) | Manuel Ramirez de la Piszina | |

| 151 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Inuvialuit | 2,500 | 1850 | Jessica M. Shadian, Mark Nuttall | ||

| 152 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Alchedoma | 2,500 | 1604 | 8 | (according to Juan de Onate - 8 villages) | aaanativearts.com/extinct-tribes |

| 153 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Ofo, Koroa & Tioux | 2,450 | 1700 | J. R. Swanton | ||

| 154 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Cowlitz | 2,400 | 1822 | 3 | Jeddediah Morse | |

| 155 | NE Woodlands | Canada Acadia | Penobscot | 2,250 | 1702 | 14 | (450 warriors) | N. H. Hist. Coll., I and J. R. Swanton |

| 156 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Tunica | 2,250 | 1698 | 7 | 260 cabins and 450 warriors | Montigny and J. R. Swanton |

| 157 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Kalispel | 2,250 | 1835-1850 | (450 warriors) | HBC agents & Joseph Lane | |

| 158 | NE Woodlands | Old Northwest | Kickapoo | 2,200 | 1825 | McKenney | ||

| 159 | Great Plains | Canada Alberta | Sarcee (Tsuutʼina) | 2,200 | 1832 | 220 tents, on average 10 people per tent | George Catlin, John Maclean | |

| 160 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Yazoo | 2,000+ | 1700 | Dumont de Montigny | ||

| 161 | NE Woodlands | New England | Nauset | 2,000 | 1600 | 24 | W. M. Denevan[74] & J. R. Swanton | |

| 162 | NE Woodlands | Middle Colonies | Wenro | 2,000 | 1600 | J. N. B. Hewitt | ||

| 163 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Slavey | 2,000 | 1857 | Emile Petitot | ||

| 165 | Southwest | Mexican Cession | Walapai | 2,000 | 1869 | J. Ross Browne | ||

| 166 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Cayuse | 2,000 | 1835 | Samuel Parker | ||

| 167 | Northwest Plateau | Canada B.C. | Sinixt | 2,000+ | 1780 | 20+ | James Teit | |

| 168 | Northwest Coast | Canada B.C. | Nuxalk (Bella Coola) | 2,000 | 1835 | Wilson Duff | ||

| 169 | NE Woodlands | Canada Ontario | Messassagnes | 2,000 | 1764 | aaanativearts.com/extinct-tribes | ||

| 170 | Great Plains | Canada Sask. | Fall Indians (Alannar) | 2,000 | 1804 | aaanativearts.com/extinct-tribes | ||

| 171 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Cusabo and Cusso | 1,900 | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 172 | Northwest Coast | Oregon Country | Chimnapum | 1,860 | 1805 | 42 lodges | Lewis and Clark | |

| 173 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Wanapum | 1,800 | 1780 | James Mooney | ||

| 174 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Wateree | 1,600 | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 175 | Northwest Coast | Oregon Country | Wappatoo area (5 tribes) | 1,590 | 1820 | aaanativearts.com/extinct-tribes | ||

| 176 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Dogrib | 1,500 | 1875 | Emile Petitot | ||

| 177 | SE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Attacapa | 1,500 | 1650 | James Mooney | ||

| 178 | Great Plains | Louisiana Purchase | Otoe | 1,500 | 1815 | (300 warriors) | William Clark | |

| 179 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Sanpoil | 1,500 | 1805 | 45+ houses | George Gibbs | |

| 180 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Wasco | 1,500 | 1838 | G. Hines | ||

| 181 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Yukon | Hankutchin | 1,500 | 1851 | (three subdivisions x 100 warriors each) | John Richardson | |

| 182 | NE Woodlands | New England | Podunk | 1,500+ | 1675 | (300 warriors fought in King Philip's War) | E. Stiles | |

| 183 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Saponi | 1,500 | 1600 | 2 | carolana.com | |

| 184 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Waxhaw and Sugaree | 1,500 | 1600 | 2 | James Mooney & carolana.com | |

| 185 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Beaver (Tsattine) | 1,250 | 1670 | James Mooney | ||

| 186 | SE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Houma | 1,225 | 1700 | J. R. Swanton | ||

| 187 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Tutelo | 1,200 | 1600 | carolana.com | ||

| 188 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Occaneechi | 1,200 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 189 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Cheraw | 1,200 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 190 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Taensa | 1,200 | 1700 | Benard de La Harpe | ||

| 191 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Machapunga | 1,200 | 1600 | 3 | carolana.com | |

| 192 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Yukon | Tutchone | 1,100 | 1910 | Frederick Webb Hodge | ||

| 193 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Waccamaw | 1,050 | 1715 | 6 | 210 warriors | W. J. Rivers |

| 194 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Guarugunve & Cuchiyaga | 1,040 | 1570 | (they inhabited Florida Keys) | Lopez de Velasco | |

| 195 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Hare | 1,000+ | 1850 | Ludwik Krzywicki | ||

| 196 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Pamlico | 1,000 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 197 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Neusiok & Coree | 1,000 | 1600 | 5 | James Mooney | |

| 198 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Chatot | 1,000+ | 1650 | Ludwik Krzywicki | ||

| 199 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Cape Fear Indians | 1,000 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 200 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Santee | 1,000 | 1600 | 2+ | James Mooney & carolana.com | |

| 201 | Great Plains | Texas Annexation | Bidai | 1,000+ | 1745 | 7 | (200+ warriors) | Athanase de Mezieres |

| 202 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Tequesta | 1,000 | 1650 | 5 | J. R. Swanton | |

| 203 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Tacobaga | 1,000 | 1650 | James Mooney | ||

| 204 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Ais | 1,000 | 1750-1785 | 40 families + additional 600 people | Ludwik Krzywicki | |

| 205 | SE Woodlands | Florida Purchase | Jeaga & Guacata | 1,000 | 1650 | James Mooney | ||

| 206 | SE Woodlands | Trans-Appalachian | Biloxi/Pascagoula/Moctobi | 1,000 | 1650 | 4 | James Mooney | |

| 207 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Moratoc | 1,000 | 1600 | carolana.com | ||

| 208 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Edisto | 1,000 | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 209 | SE Woodlands | Texas Annexation | Aranama | 870+ | 1778 | Athanase de Mezieres | ||

| 210 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Sewee | 800+ | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 211 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Congaree | 800 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 212 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Sissipahaw | 800 | 1600 | 1 | James Mooney & carolana.com | |

| 213 | NE Woodlands | New England | Paugussett | 800 | 1600 | C. Thomas in F. W. Hodge | ||

| 214 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Meherrin | 700 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 215 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada Ontario | Abittibi | 700 | 1736 | (140 warriors) | Michel de La Chauvignerie | |

| 216 | Subarctic & Arctic | Canada | Yellowknives | 600+ | 1877 | 70+ tents | Emile Petitot | |

| 217 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Etiwaw (also Etiwan) | 600 | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 218 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Woccon | 600 | 1701 | 2 | (120 warriors) | John Lawson, "History of Carolina" |

| 219 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Peedee | 600 | 1600 | 1 | James Mooney & carolana.com | |

| 220 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Keyauwee | 600 | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 221 | NE Woodlands | New England | Quinnipiac | 550 | 1730 | John William De Forest | ||

| 222 | NE Woodlands | New England | Manisses | 500 | 1500 | Capers Jones[77] | ||

| 223 | Northwest Plateau | Oregon Country | Takelma and Latgawa | 500 | 1780 | James Mooney | ||

| 224 | NE Woodlands | New England | Tunxis | 500 | 1600 | (100 warriors) | John William De Forest | |

| 225 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Chiaha in South Carolina | 500 | 1600 | carolana.com | ||

| 226 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Hatteras | 500 | 1600 | carolana.com | ||

| 227 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Eno | 500 | 1600 | 1 | James Mooney & carolana.com | |

| 228 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Shakori | 500 | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 229 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Adshusheer | 500 | 1600 | James Mooney & carolana.com | ||

| 230 | NE Woodlands | New England | Wangunk | 400 | 1600 | James Mooney | ||

| 231 | SE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Avoyel | 400 | 1698 | 32 cabins (and 80 warriors) | J. R. Swanton | |

| 232 | Northwest Coast | Oregon Country | Squaxon | 375 | 1857 | John Ross Browne | ||

| 233 | NE Woodlands | Louisiana Purchase | Ahwajiaway | 200 | 1805 | aaanativearts.com/extinct-tribes | ||

| 234 | SE Woodlands | Southern Colonies | Winyaw | 180 | 1715 | 1 | (36 warriors and one village) | carolana.com |

| 235 | California | Mexican Cession | up to 600 micro-tribes | 340,000 | 1769 | Cook, Jones & Codding,[79] Field[80] | ||

| 236 | Subarctic & Arctic | Alaska | Alaska Native tribes | 93,800 | 1750 | Steve Langdon[81] |

The total peak population size only for the tribes listed in this table is 3,210,215 in the US and Canada (including 327,600 in Canada).

Pre-Columbian Americas

Genetic diversity and population structure in the American land mass using DNA micro-satellite markers (genotype) sampled from North, Central, and South America have been analyzed against similar data available from other Indigenous populations worldwide.[82][83] The Amerindian populations show a lower genetic diversity than populations from other continental regions.[83] Decreasing genetic diversity with increasing geographic distance from the Bering Strait can be seen, as well as a decreasing genetic similarity to Siberian populations from Alaska (genetic entry point).[82][83] A higher level of diversity and lower level of population structure in western South America compared to eastern South America is observed.[82][83] A relative lack of differentiation between Mesoamerican and Andean populations is a scenario that implies coastal routes were easier than inland routes for migrating peoples (Paleo-Indians) to traverse.[82] The overall pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were recently colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70–250), and then they grew by a factor of 10 over 800–1,000 years.[84][85] The data also show that there have been genetic exchanges between Asia, the Arctic and Greenland since the initial peopling of the Americas.[85][86] A new study in early 2018 suggests that the effective population size of the original founding population of Native Americans was about 250 people.[87][88]

Depopulation by Old World diseases

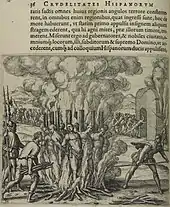

Early explanations for the population decline of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas include the brutal practices of the Spanish conquistadores, as recorded by the Spaniards themselves, such as the encomienda system, which was ostensibly set up to protect people from warring tribes as well as to teach them the Spanish language and the Catholic religion, but in practice was tantamount to serfdom and slavery.[89] The most notable account was that of the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, whose writings vividly depict Spanish atrocities committed in particular against the Taínos.[90] The second European explanation was a perceived divine approval, in which God removed the natives as part of His "divine plan" to make way for a new Christian civilization. Many Native Americans viewed their troubles in a religious framework within their own belief systems.[91]

According to later academics such as Noble David Cook, a community of scholars began "quietly accumulating piece by piece data on early epidemics in the Americas and their relation to the subjugation of native peoples." Scholars like Cook believe that widespread epidemic disease, to which the natives had no prior exposure or resistance, was the primary cause of the massive population decline of the Native Americans.[92] One of the most devastating diseases was smallpox, but other deadly diseases included typhus, measles, influenza, bubonic plague, cholera, malaria, tuberculosis, mumps, yellow fever and pertussis, which were chronic in Eurasia.[93]

However, recently scholars have studied the link between physical colonial violence such as warfare, displacement, and enslavement, and the proliferation of disease among Native populations.[4][94] For example, according to Coquille scholar Dina Gilio-Whitaker, "In recent decades, however, researchers challenge the idea that disease is solely responsible for the rapid Indigenous population decline. The research identifies other aspects of European contact that had profoundly negative impacts on Native peoples' ability to survive foreign invasion: war, massacres, enslavement, overwork, deportation, the loss of will to live or reproduce, malnutrition and starvation from the breakdown of trade networks, and the loss of subsistence food production due to land loss."[95]

Further, Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis points out that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, implying that, until that date, epidemic disease played no significant part in the depopulation of the Antilles. The practices of forced labor, brutal punishment, and inadequate necessities of life, were the initial and major reasons for depopulation.[96] Jason Hickel estimates that a third of Arawak workers died every six months from forced labor in these mines.[97] In this way, "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, as it set the conditions for diseases such as smallpox, influenza, and malaria to flourish.[96] Unlike the populations of Europe who rebounded following the Black Death, no such rebound occurred for the Indigenous populations.[96]

Similarly, historian Jeffrey Ostler at the University of Oregon has argued that population collapses in North America throughout colonization were not mainly due to lack of Native immunity to European disease. Instead, he claims that "When severe epidemics did hit, it was often less because Native bodies lacked immunity than because European colonialism disrupted Native communities and damaged their resources, making them more vulnerable to pathogens." In specific regard to Spanish colonization of northern Florida and southeastern Georgia, Native peoples there "were subject to forced labor and, because of poor living conditions and malnutrition, succumbed to wave after wave of unidentifiable diseases." Further, in relation to British colonization in the Northeast, Algonquian speaking tribes in Virginia and Maryland "suffered from a variety of diseases, including malaria, typhus, and possibly smallpox." These diseases were not solely a case of Native susceptibility, however, because "as colonists took their resources, Native communities were subject to malnutrition, starvation, and social stress, all making people more vulnerable to pathogens. Repeated epidemics created additional trauma and population loss, which in turn disrupted the provision of healthcare." Such conditions would continue, alongside rampant disease in Native communities, throughout colonization, the formation of the United States, and multiple forced removals, as Ostler explains that many scholars "have yet to come to grips with how U.S. expansion created conditions that made Native communities acutely vulnerable to pathogens and how severely disease impacted them. ... Historians continue to ignore the catastrophic impact of disease and its relationship to U.S. policy and action even when it is right before their eyes."[6]

Historian David Stannard says that by "focusing almost entirely on disease ... contemporary authors increasingly have created the impression that the eradication of those tens of millions of people was inadvertent—a sad, but both inevitable and "unintended consequence" of human migration and progress," and asserts that their destruction "was neither inadvertent nor inevitable," but the result of microbial pestilence and purposeful genocide working in tandem.[98] He also wrote:[99]

...Despite frequent undocumented assertions that disease was responsible for the great majority of indigenous deaths in the Americas, there does not exist a single scholarly work that even pretends to demonstrate this claim on the basis of solid evidence. And that is because there is no such evidence, anywhere. The supposed truism that more native people died from disease than from direct face-to-face killing or from gross mistreatment or other concomitant derivatives of that brutality such as starvation, exposure, exhaustion, or despair is nothing more than a scholarly article of faith...

In contrast, historian Russel Thornton has pointed out that there were disastrous epidemics and population losses during the first half of the sixteenth century “resulting from incidental contact, or even without direct contact, as disease spread from one American Indian tribe to another.” [100] Thornton has also challenged higher Indigenous population estimates, which are based on the Malthusian assumption that “populations tend to increase to, and beyond, the limits of the food available to them at any particular level of technology."[101]

The European colonization of the Americas resulted in the deaths of so many people it contributed to climatic change and temporary global cooling, according to scientists from University College London.[102][103] A century after the arrival of Christopher Columbus, some 90% of Indigenous Americans had perished from "wave after wave of disease", along with mass slavery and war, in what researchers have described as the "great dying".[104] According to one of the researchers, UCL Geography Professor Mark Maslin, the large death toll also boosted the economies of Europe: "the depopulation of the Americas may have inadvertently allowed the Europeans to dominate the world. It also allowed for the Industrial Revolution and for Europeans to continue that domination."[105]

Biological warfare

When Old World diseases were first carried to the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century, they spread throughout the southern and northern hemispheres, leaving the Indigenous populations in near ruins.[93][106] No evidence has been discovered that the earliest Spanish colonists and missionaries deliberately attempted to infect the American natives, and some efforts were made to limit the devastating effects of disease before it killed off what remained of their labor force (compelled to work under the encomienda system).[93][106] The cattle introduced by the Spanish contaminated various water reserves which Native Americans dug in the fields to accumulate rainwater. In response, the Franciscans and Dominicans created public fountains and aqueducts to guarantee access to drinking water.[21] But when the Franciscans lost their privileges in 1572, many of these fountains were no longer guarded and so deliberate well poisoning may have happened.[21] Although no proof of such poisoning has been found, some historians believe the decrease of the population correlates with the end of religious orders' control of the water.[21]

In the centuries that followed, accusations and discussions of biological warfare were common. Well-documented accounts of incidents involving both threats and acts of deliberate infection are very rare, but may have occurred more frequently than scholars have previously acknowledged.[107][108] Many of the instances likely went unreported, and it is possible that documents relating to such acts were deliberately destroyed,[108] or sanitized.[109][110] By the middle of the 18th century, colonists had the knowledge and technology to attempt biological warfare with the smallpox virus. They well understood the concept of quarantine, and that contact with the sick could infect the healthy with smallpox, and those who survived the illness would not be infected again. Whether the threats were carried out, or how effective individual attempts were, is uncertain.[93][108][109]

One such threat was delivered by fur trader James McDougall, who is quoted as saying to a gathering of local chiefs, "You know the smallpox. Listen: I am the smallpox chief. In this bottle I have it confined. All I have to do is to pull the cork, send it forth among you, and you are dead men. But this is for my enemies and not my friends."[111] Likewise, another fur trader threatened Pawnee Indians that if they didn't agree to certain conditions, "he would let the smallpox out of a bottle and destroy them." The Reverend Isaac McCoy was quoted in his History of Baptist Indian Missions as saying that the white men had deliberately spread smallpox among the Indians of the southwest, including the Pawnee tribe, and the havoc it made was reported to General Clark and the Secretary of War.[111][112] Artist and writer George Catlin observed that Native Americans were also suspicious of vaccination, "They see white men urging the operation so earnestly they decide that it must be some new mode or trick of the pale face by which they hope to gain some new advantage over them."[113] So great was the distrust of the settlers that the Mandan chief Four Bears denounced the white man, whom he had previously treated as brothers, for deliberately bringing the disease to his people.[114][115][116]

During the siege of British-held Fort Pitt in the Seven Years' War, Colonel Henry Bouquet ordered his men to take smallpox-infested blankets from their hospital and gave them as gifts to two neutral Lenape Indian dignitaries during a peace settlement negotiation, according to the entry in the Captain's ledger, "To convey the Smallpox to the Indians".[109][117][118] In the following weeks, Sir Jeffrey Amherst conspired with Bouquet to "Extirpate this Execreble Race" of Native Americans, writing, "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them." His Colonel agreed to try.[108][117]

Most scholars have asserted that the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic was "started among the tribes of the upper Missouri River by failure to quarantine steamboats on the river",[111] and Captain Pratt of the St. Peter "was guilty of contributing to the deaths of thousands of innocent people. The law calls his offense criminal negligence. Yet in light of all the deaths, the almost complete annihilation of the Mandans, and the terrible suffering the region endured, the label criminal negligence is benign, hardly befitting an action that had such horrendous consequences."[115] However, some sources attribute the 1836–40 epidemic to the deliberate communication of smallpox to Native Americans, with historian Ann F. Ramenofsky writing, "Variola Major can be transmitted through contaminated articles such as clothing or blankets. In the nineteenth century, the U. S. Army sent contaminated blankets to Native Americans, especially Plains groups, to control the Indian problem."[119] In Brazil, well into the 20th century, deliberate infection attacks continued as Brazilian settlers and miners transported infections intentionally to the native groups whose lands they coveted.[106]

Vaccination

After Edward Jenner's 1796 demonstration that the smallpox vaccination worked, the technique became better known and smallpox became less deadly in the United States and elsewhere. Many colonists and natives were vaccinated, although, in some cases, officials tried to vaccinate natives only to discover that the disease was too widespread to stop. At other times, trade demands led to broken quarantines. In other cases, natives refused vaccination because of suspicion of whites. The first international healthcare expedition in history was the Balmis expedition which had the aim of vaccinating Indigenous peoples against smallpox all along the Spanish Empire in 1803. In 1831, government officials vaccinated the Yankton Sioux at Sioux Agency. The Santee Sioux refused vaccination and many died.[36]

Depopulation by European conquest

War and violence

While epidemic disease was a leading factor of the population decline of the American Indigenous peoples after 1492, there were other contributing factors, all of them related to European contact and colonization. One of these factors was warfare. According to demographer Russell Thornton, although many people died in wars over the centuries, and war sometimes contributed to the near extinction of certain tribes, warfare and death by other violent means was a comparatively minor cause of overall native population decline.[120]

From the U.S. Bureau of the Census in 1894, wars between the government and the Indigenous peoples ranged over 40 in number over the previous 100 years. These wars cost the lives of approximately 19,000 white people, and the lives of about 30,000 Indians, including men, women, and children. They safely estimated that the amount of Native people who were killed or wounded was actually around fifty percent more than what was recorded.[121]

There is some disagreement among scholars about how widespread warfare was in pre-Columbian America,[122] but there is general agreement that war became deadlier after the arrival of the Europeans and their firearms. The South or Central American infrastructure allowed for thousands of European conquistadors and tens of thousands of their Indian auxiliaries to attack the dominant Indigenous civilization. Empires such as the Incas depended on a highly centralized administration for the distribution of resources. Disruption caused by the war and the colonization hampered the traditional economy, and possibly led to shortages of food and materials.[123] Across the western hemisphere, war with various Native American civilizations constituted alliances based out of both necessity or economic prosperity and, resulted in mass-scale intertribal warfare.[124] European colonization in the North American continent also contributed to a number of wars between Native Americans, who fought over which of them should have first access to new technology and weaponry—like in the Beaver Wars.[125]

Exploitation

Some Spaniards objected to the encomienda system of labor, notably Bartolomé de las Casas, who insisted that the Indigenous people were humans with souls and rights. Due to many revolts and military encounters, Emperor Charles V helped relieve the strain on both the native laborers and the Spanish vanguards probing the Caribana for military and diplomatic purposes.[126] Later on New Laws were promulgated in Spain in 1542 to protect isolated natives, but the abuses in the Americas were never entirely or permanently abolished. The Spanish also employed the pre-Columbian draft system called the mita,[127] and treated their subjects as something between slaves and serfs. Serfs stayed to work the land; slaves were exported to the mines, where large numbers of them died. In other areas the Spaniards replaced the ruling Aztecs and Incas and divided the conquered lands among themselves ruling as the new feudal lords with often, but unsuccessful lobbying to the viceroys of the Spanish crown to pay Tlaxcalan war demnities. The infamous Bandeirantes from São Paulo, adventurers mostly of mixed Portuguese and native ancestry, penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves. Serfdom existed as such in parts of Latin America well into the 19th century, past independence.[128] Historian Andrés Reséndez argues that even though the Spanish were aware of the spread of smallpox, they made no mention of it until 1519, a quarter century after Columbus arrived in Hispaniola.[129] Instead he contends that enslavement in gold and silver mines was the primary reason why the Native American population of Hispaniola dropped so significantly.[128][129] and that even though disease was a factor, the native population would have rebounded the same way Europeans did following the Black Death if it were not for the constant enslavement they were subject to.[129] He further contends that enslavement of Native Americans was in fact the primary cause of their depopulation in Spanish territories;[129] that the majority of Indians enslaved were women and children compared to the enslavement of Africans which mostly targeted adult males and in turn they were sold at a 50% to 60% higher price,[130] and that 2,462,000 to 4,985,000 Amerindians were enslaved between Columbus's arrival and 1900.[131][130]

Massacres

- The Pequot War in early New England.

- In mid-19th century Argentina, post-independence leaders Juan Manuel de Rosas and Julio Argentino Roca engaged in what they presented as a "Conquest of the Desert" against the natives of the Argentinian interior, leaving over 1,300 Indigenous dead.[132][133]

- While some California tribes were settled on reservations, others were hunted down and massacred by 19th century American settlers. It is estimated that at least 9,400 to 16,000 California Indians were killed by non-Indians, mostly occurring in more than 370 massacres (defined as the "intentional killing of five or more disarmed combatants or largely unarmed noncombatants, including women, children, and prisoners, whether in the context of a battle or otherwise").[134][135]

Displacement and disruption

Throughout history, Indigenous people have been subjected to the repeated and forced removal from their land. Beginning in the 1830s, there was the relocation of an estimated 100,000 Indigenous people in the United States called the “Trail of Tears".[136] The tribes affected by this specific removal were the Five Civilized Tribes: The Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole. The treaty of New Echota,[137] was enacted, which stated that the United States “would give Cherokee land west of the Mississippi in exchange for $5,000,000”.[136] According to Jeffrey Ostler, "Of the 80,000 Native people who were forced west from 1830 into the 1850s, between 12,000 and 17,000 perished." Ostler states that "the large majority died of interrelated factors of starvation, exposure and disease".[138]

In addition to the removal of the Southern Tribes, there were multiple other removals of Northern Tribes also known as "Trails of Tears." For example, "In the free labor states of the North, federal and state officials, supported by farmers, speculators and business interests, evicted Shawnees, Delawares, Senecas, Potawatomis, Miamis, Wyandots, Ho-Chunks, Ojibwes, Sauks and Meskwakis." These Nations were moved West of the Mississippi into what is now known as Eastern Kansas, and numbered 17,000 on arrival. According to Ostler, "by 1860, their numbers had been cut in half" due to low fertility, high infant mortality, and increased disease caused by conditions such as polluted drinking water, few resources, and social stress.[138]

Ostler also writes that the areas that Northern tribes were removed to were already inhabited: "The areas west of the Mississippi River were home to other Indigenous nations— Osages, Kanzas, Omahas, Ioways, Otoes and Missourias. To make room for thousands of people from the East, the government dispossessed these nations of much their lands." Ostler writes that in 1840, when Northern Nations were moved onto their land, "The combined population of these western nations was 9,000 ... 20 years later, it had fallen to 6,000."[138]

Later apologies by government officials

On 8 September 2000, the head of the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) formally apologized for the agency's participation in the ethnic cleansing of Western tribes.[139][140][141] In a speech before representatives of Native American peoples in June 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom apologized for the "California Genocide." Newsom said, "That's what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that's the way it needs to be described in the history books."[142]

See also

- Indigenous peoples in Canada

- Native Americans in the United States

- History of Native Americans in the United States

- List of Indian massacres

- List of Indian reserves in Canada by population

- List of Indian reservations in the United States

- Amazonas before the Inca Empire

- American Indian Wars

- Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Conquest of the Desert

- Genocide of indigenous peoples

- Genocides in the Americas

- Guatemalan genocide

- Selknam genocide

- Smallpox epidemics in the Americas

- Trail of Tears

- Indigenous peoples

- Uncontacted peoples

- Racism in Canada#Indigenous peoples

- Racism in North America

- Racism in South America

- Racism in the United States#Native Americans

Notes

- Extrapolated from 30,000 warriors (× 5) in year 1762, according to James Gorrell. Almost a century later, in 1841, George Catlin estimated the Sioux as up to 50,000 people, and mentioned that they had just lost approx. 8,000 dead to smallpox a few years prior.

- Over 70 towns or villages and 25,000 warriors.

- They had 60 towns and 20,000 warriors. One of their towns - Cahokia - contained 400 lodges and was inhabited by 1,800 warriors.

- "The epidemic of 1837-38 was disastrous, approx. 15,000 Blackfeet people fell victim to the disease."

- Five Nations, on average 14,000 per nation.

- They had approx. 7 pueblos (towns), one of which - Oraibi (possibly the largest of all) - had 14,000 inhabitants before an epidemic.

- It was also reported they had 25-32 towns or villages.

- Extrapolated from 8,000 warriors × 5.

- 38 villages (on average 130-150 lodges/cabins per village) with 7,600 warriors x 5 = 38,000 total population, not including the Arikara.

- Over 65 towns or villages and 6,000 warriors in 1730-35.

- They had approx. 6,000 warriors and 24 towns.

- They inhabited up to 11 pueblos (towns).

- They had approx. 4,000 warriors and ca. 40 villages.

- Later an epidemic ravaged them in 1618.

- They inhabited up to 7 pueblos (towns).

- Extrapolated from 3,000 warriors × 5.

References

Notes

- Taylor, Alan (2002). American colonies; Volume 1 of The Penguin history of the United States, History of the United States Series. Penguin. p. 40. ISBN 978-0142002100. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- David E. Stannard (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- Ostler, Jeffrey (29 April 2020). "Disease Has Never Been Just Disease for Native Americans". The Atlantic. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- Edwards, Tai S; Kelton, Paul (1 June 2020). "Germs, Genocides, and America's Indigenous Peoples". Journal of American History. 107 (1): 52–76. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaaa008. ISSN 0021-8723.

- David E. Stannard (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- Ostler, Jeffrey (2019). Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. Yale University Press. pp. 11–17, 381. ISBN 9780300245264.

Since 1992, the argument for a total, relentless, and pervasive genocide in the Americas has become accepted in some areas of Indigenous studies and genocide studies. For the most part, however, this argument has had little impact on mainstream scholarship in U.S. history or American Indian history. Scholars are more inclined than they once were to gesture to particular actions, events, impulses, and effects as genocidal, but genocide has not become a key concept in scholarship in these fields.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An Indigenous Peoples History of the United States. Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807000410.

- Alvarez, Alex (2015). "Gary Clayton Anderson. Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime That Should Haunt America". The American Historical Review. 120 (2): 605–606. doi:10.1093/ahr/120.2.605. ISSN 1937-5239.

- Feinstein, Stephen (2006). "God, Greed, and Genocide: The Holocaust Through the Centuries, by Arthur Grenke". Canadian Journal of History. 41 (1): 197–199. doi:10.3138/cjh.41.1.197. ISSN 0008-4107.

For the most part, however, the diseases that decimated the Natives were caused by natural contact. These Native peoples were greatly weakened, and as a result, they were less able to resist the Europeans. However, diseases themselves were rarely the sources of the genocides nor were they the sources of the deaths which were caused by genocidal means. The genocides were caused by the aggressive actions of one group towards another.

- Denevan, William M. (15 March 1992). UW Press - : The Native Population of the Americas in 1492: Second Revised Edition, edited by William M. Denevan, With a Foreword by W. George Lovell. ISBN 978-0-299-13434-1.

- Michael R. Haines; Richard H. Steckel (2000). A Population History of North America. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7.

- 20th century estimates in Thornton, p. 22; Denevan's consensus count; recent lower estimates. Archived 28 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Denevan, William M. (September 1992). "The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 369–385. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01965.x.

- Fernandes, Daniel M.; Sirak, Kendra A.; Ringbauer, Harald; Sedig, Jakob; Rohland, Nadin; Cheronet, Olivia; Mah, Matthew; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Culleton, Brendan J.; Adamski, Nicole; Bernardos, Rebecca; Bravo, Guillermo; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Callan, Kimberly (February 2021). "A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean". Nature. 590 (7844): 103–110. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..103F. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7864882. PMID 33361817.

- Stannard 1993, p. 151.

- Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (1 March 2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004. ISSN 0277-3791. S2CID 133664669.

- Woodward, Aylin. "European colonizers killed so many indigenous Americans that the planet cooled down, a group of researchers concluded". Business Insider. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Geggel, Laura (8 February 2019). "European Slaughter of Indigenous Americans May Have Cooled the Planet". Live Science. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Rayner, Peter; Trudinger, Cathy; Etheridge, David; Rubino, Mauro (26 July 2016). "Land carbon storage swelled in the Little Ice Age, which bodes ill for the future". Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Thornton, pp. xvii, 36.

- "La catastrophe démographique" (The Demographic Catastrophe"), L'Histoire n°322, July–August 2007, p. 17.

- Alves-Silva, Juliana; da Silva Santos, Magda; Guimarães, Pedro E.M.; Ferreira, Alessandro C.S.; Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Pena, Sérgio D.J.; Prado, Vania Ferreira (August 2000). "The Ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA Lineages". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (2): 444–461. doi:10.1086/303004. PMC 1287189. PMID 10873790.

- Snow, D. R. (16 June 1995). "Microchronology and Demographic Evidence Relating to the Size of Pre-Columbian North American Indian Populations". Science. 268 (5217): 1601–1604. Bibcode:1995Sci...268.1601S. doi:10.1126/science.268.5217.1601. PMID 17754613. S2CID 8512954.

- Thornton, Russell (1990). American Indian holocaust and survival: a population history since 1492. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 26–32. ISBN 978-0-8061-2220-5.

- Dobyns, Henry (1983). Their Number Become Thinned: Native American Dynamics in Eastern North America. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- Michael R. Haines; Richard H. Steckel (2000). A Population History of North America. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7.

- Herbert C. Northcott; Donna Marie Wilson (2008). Dying And Death in Canada. University of Toronto Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-55111-873-4.

- Michael R. Haines; Richard H. Steckel (2000). A Population History of North America. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7.

- Garrick Alan Bailey; William C ... Sturtevant; Smithsonian Institution (U S ) (2008). Handbook of North American Indians: Indians in Contemporary Society. Government Printing Office. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-16-080388-8.

- David L. Preston (2009). The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667-1783. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-8032-2549-7.

- William G. Dean; Geoffrey J. Matthews (1998). Concise Historical Atlas of Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8020-4203-3.

- R. G. Robertson (2001). Rotting Face : Smallpox and the American Indian. University of Nebraska. ISBN 978-0-87004-497-7.

- "Censuses of Canada 1665 to 1871: Aboriginal peoples". Statistics Canada. 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (25 October 2017). "The Daily — Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census". www150.statcan.gc.ca.

- "Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit". Statistics Canada. 2012.

- Krech III, Shepard (1999). The Ecological Indian: Myth and History (1 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-0-393-04755-4.

- Jennings 1993, p. 83

- Henige, p. 182.

- Karl Sapper. Das Element der Wirklichkeit und die Welt der Erfahrung. Grundlinien einer anthropozentrischen Naturphilosophie (in German). C.H. Beck..

- Alfred Louis Kroeber, Cultural and Natural Areas of Native North America, University of California Press.

Kroeber inclut seulement le Honduras et le Nicaragua dans l'Amérique centrale ; il inclut le Guatemala et le Salvador au Mexique, et le Costa Rica et le Panama aux terres basses sudaméricaines. - James H. Steward, « The Native population of South America » in Handbook of South American Indians, tome V, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, p. 655-668.

- Ángel Rosenblat, Población indígena y el mestizaje en América, Nova

- Henry F. Dobyns, « Estimating aboriginal population: an appraisal of techniques with a new hemispheric estimate », in Current Anthropology, 7, n°4, octobre 1966, p.395-449.

- Ubelaker, Douglas H. (1988). "North American Indian Population Size, A.D. 1500 to 1985". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 77 (3): 289–294. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330770302.

- Denevan, William (1994). The Native Population of the Americas, 1492.

- Snow, Dean R. (2001). "Setting Demographic Limits: The North American Case".

- Suzanne Austin Alchon, A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective, University of New Mexico Press, p.147-172.

- Thornton, Russell (2005). "Native American Demographic and Tribal Survival into the Twenty-first Century". American Studies. 46:3/4 (3/4): 23–38. JSTOR 40643888.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. pp. 318–543.

- Royce Blaine, Martha (1979). The Ioway Indians. p. 45. ISBN 9780806127286.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 537.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. pp. 505–506.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 530.

- De Benavides, Fray Alonso (1945). Revised Memorial Of 1634. Vol. IV. The University of New Mexico Press.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 541.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 534.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 514.

- Jaimes, M. Annette (1992). The State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization, and Resistance. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press. p. 38.

- Drake, Samuel Gardner (1849). Biography and history of the Indians of North America. Boston: Benjamin B. Mussey & Co. pp. 9–11.

- Drake, Samuel Gardner (1880). The aboriginal races of North America. New York: J. B. Alden. pp. 9–11.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 538.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 460.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. pp. 539–540.

- Domenech, Emmanuel (1860). Seven Years' Residence in the Great Deserts of North America. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. pp. 16, 47–48.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 500.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 535.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 515.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 539.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 465.

- Sanstead, Dr. Wayne G. (2002). The history and culture of the Mandan, Hidatsa, Sahnish (Arikara) (PDF). Bismarck, North Dakota: North Dakota Department of Public Instruction. p. 6.

- Bray, Kingsley M. (1994). "Teton Sioux: Population History, 1655-1881" (PDF). Nebraska History. 75: 165–188 – via Nebraska State Historical Society.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 523.

- Krzywicki, Ludwik (1934). Primitive society and its vital statistics. Publications of the Polish Sociological Institute. London: Macmillan. p. 417.

- Denevan, William M. (1992). The Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 251–272.

- Scaife, Hazel Lewis (1896). History and Condition of the Catawba Indians of South Carolina. Philadelphia: Office of Indian Rights Association. p. 5.

- Swanton, John R. (1953). The Indian Tribes of North America. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin145. Washington: Bureau of American Ethnology. p. 56.

- Jones, Capers (2006). The History and Future of Narragansett Bay. Boca Raton, Florida: Universal Publishers.

- Upton, Leslie (1977). "The Extermination of the Beothucks of Newfoundland". Canadian Historical Review (58): 134.

- Jones, Terry L.; Codding, Brian F. (2019). "The Native California Commons: Ethnographic and Archaeological Perspectives on Land Control, Resource Use, and Management". Global Perspectives on Long Term Community Resource Management. Studies in Human Ecology and Adaptation. Vol. Global Perspectives on Long Term Community Resource Management. pp. 256–263. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15800-2_12. ISBN 978-3-030-15799-9. S2CID 197573059.

- Field, Margaret A. (1993). Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873. Boston: University of Massachusetts Boston. pp. 13 (map).

- Sandberg, Eric (2013). A history of Alaska population settlement (PDF). Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development. pp. 4–6.

- Wang, Sijia; Lewis, Cecil M; Jakobsson, Mattias; Ramachandran, Sohini; Ray, Nicolas; Bedoya, Gabriel; Rojas, Winston; Parra, Maria V; Molina, Julio A; Gallo, Carla; Mazzotti, Guido; Poletti, Giovanni; Hill, Kim; Hurtado, Ana M; Labuda, Damian; Klitz, William; Barrantes, Ramiro; Bortolini, Maria Cátira; Salzano, Francisco M; Petzl-Erler, Maria Luiza; Tsuneto, Luiza T; Llop, Elena; Rothhammer, Francisco; Excoffier, Laurent; Feldman, Marcus W; Rosenberg, Noah A; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés (23 November 2007). "Genetic Variation and Population Structure in Native Americans". PLOS Genetics. 3 (11): e185. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030185. PMC 2082466. PMID 18039031.

- Walsh, Bruce; Redd, Alan J.; Hammer, Michael F. (January 2008). "Joint match probabilities for Y chromosomal and autosomal markers". Forensic Science International. 174 (2–3): 234–238. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.03.014. PMID 17449208.

- Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man – A Genetic Odyssey (Digitised online by Google books). Random House. pp. 138–40. ISBN 978-0-8129-7146-0. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- Hey, Jody (24 May 2005). "On the Number of New World Founders: A Population Genetic Portrait of the Peopling of the Americas". PLOS Biology. 3 (6): e193. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030193. PMC 1131883. PMID 15898833.

- Wade, Nicholas (2010). "Ancient Man In Greenland Has Genome Decoded". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- "DNA sequences suggest 250 people made up original Native American founding population". The University of Kansas. 27 April 2018.

- Fagundes, Nelson J.R.; Tagliani-Ribeiro, Alice; Rubicz, Rohina; Tarskaia, Larissa; Crawford, Michael H.; Salzano, Francisco M.; Bonatto, Sandro L. (2018). "How strong was the bottleneck associated to the peopling of the Americas? New insights from multilocus sequence data". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 41 (1 suppl 1): 206–214. doi:10.1590/1678-4685-gmb-2017-0087. PMC 5913727. PMID 29668018. S2CID 4951783.

- Junius P. Rodriguez (2007). Encyclopedia of slave resistance and rebellion. Vol. 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-313-33272-2. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioLife. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-113-14760-8. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- Guilmet, George M; Boyd, Robert T; Whited, David L; Thompson, Nile (1991). "The Legacy of Introduced Disease: The Southern Coast Salish". American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 15 (4): 1–32. doi:10.17953/aicr.15.4.133g8x7135072136.

- Cook, Noble David. Born To Die; Cambridge University Press; 1998; pp. 1–14.

- The First Horseman: Disease in Human History; John Aberth; Pearson-Prentice Hall (2007); pp. 47–75 (51)

- Herzog, Richard (23 September 2020). "How Aztecs Reacted to Colonial Epidemics". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- Gilio-Whitaker, Dina (2019). As long as grass grows : the indigenous fight for environmental justice, from colonization to Standing Rock. Boston, Massachusetts. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8070-7378-0. OCLC 1044542033.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-547-64098-3.

- Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-78609-003-4.

- David E. Stannard (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- Stannard, David E. (1996). Uniqueness as Denial: The Politics of Genocide Scholarship. Westview Press. p. 255. ISBN 0813326419.

- Thomas Michael Swensen (2015). "Of Subjection and Sovereignty: Alaska Native Corporations and Tribal Governments in the Twenty-First Century". Wíčazo Ša Review. 30 (1): 100. doi:10.5749/wicazosareview.30.1.0100. ISSN 0749-6427. S2CID 159338399.