Lohengrin (opera)

Lohengrin (pronounced [ˈloːənˌɡʁiːn] in German), WWV 75, is a Romantic opera in three acts composed and written by Richard Wagner, first performed in 1850. The story of the eponymous character is taken from medieval German romance, notably the Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach, and its sequel Lohengrin, itself inspired by the epic of Garin le Loherain. It is part of the Knight of the Swan legend.

| Lohengrin | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Richard Wagner | |

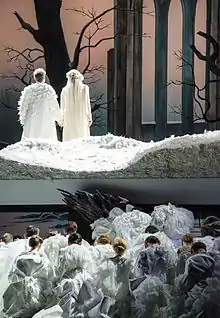

Production of the Oslo Opera in 2015 | |

| Librettist | Richard Wagner |

| Language | German |

| Based on | Medieval German Romance |

| Premiere | |

The opera has inspired other works of art. King Ludwig II of Bavaria named his castle Neuschwanstein Castle after the Swan Knight. It was King Ludwig's patronage that later gave Wagner the means and opportunity to complete, build a theatre for, and stage his epic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen. He had discontinued composing it at the end of Act II of Siegfried, the third of the Ring tetralogy, to create his radical chromatic masterpiece of the late 1850s, Tristan und Isolde, and his lyrical comic opera of the mid-1860s, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

The most popular and recognizable part of the opera is the Bridal Chorus, colloquially known in English-speaking countries as "Here Comes the Bride," usually played as a processional at weddings. The orchestral preludes to Acts I and III are also frequently performed separately as concert pieces.

The autograph manuscript of the opera is preserved in the Richard Wagner Foundation.

Literary background

The literary figure of Lohengrin first appeared as a supporting character in the final chapter of the medieval epic poem Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach. The Grail Knight Lohengrin, son of the Grail King Parzival, is sent to the duchess of Brabant to defend her. His protection comes under the condition that she must never ask his name. If she violates this requirement, he will be forced to leave her.[1] Wagner took up these characters and set the "forbidden question" theme at the core of a story which makes contrasts between the godly and the mundane, and between Early Middle Age Christendom and Germanic paganism. Wagner attempted at the same time to weave elements of Greek tragedy into the plot. He wrote the following in Mitteilungen an meine Freunde about his Lohengrin plans:

Who doesn't know "Zeus and Semele"? The god is in love with a human woman and approaches her in human form. The lover finds that she cannot recognize the god in this form, and demands that he should make the real sensual form of his being known. Zeus knows that she would be destroyed by the sight of his real self. He suffers in this awareness, suffers knowing that he must fulfill this demand and in doing so ruin their love. He will seal his own doom when the gleam of his godly form destroys his lover. Is the man who craves for God not destroyed?[2]

Composition

Lohengrin was written and composed between 1845 and 1848 when Wagner worked as Kapellmeister at the Royal Dresden court. The opera's genesis, however, starts some years earlier when Wagner was living and working in Paris. By late 1841, Wagner had conceived a five-act historical opera based on the Hohenstaufen dynasty entitled Die Sarazenin (The Saracen Woman)[3] and, although he lavished on it all the trappings of Grand Opera, his attention was soon distracted by a Volksbuch that he obtained through his friendship with the philologist Samuel Lehrs. The book in question was Ludwig Bechstein's 1835 anthology of legends Der Sagenschatz und die Sagenkreise des Thüringerlandes.[4] As well as being the means by which Wagner first became aware of the Lohengrin legend, the anthology also retold the tale of Tannhäuser.[5]

Seeking a more authentic picture of the Tannhäuser legend, Lehrs then provided Wagner with the annual proceedings of the Königsberg Germanic Society which not only included C.T.L. Lucas's critical study of the "Wartburg war" but also included a piece of criticism about the poem Lohengrin, together with a lengthy narrative of the rambling epic's principal content. Thus, Wagner admits, with one blow a whole new world was opened to him,[6] and although unable to find the form to master the material for his own dramatic purpose, he could clearly visualize Lohengrin and it remained as an inextinguishable image within him.[7]

Stewart Spencer neither regards the abandonment of the Hohenstaufen projects during the 1840s at this time nor, more specifically, in the musical and formal dissimilarities between Rienzi and Der fliegende Holländer as symptomatic of a fundamental turn from history towards myth.[8] Instead Spencer argues that Wagner did not draw any fundamental distinction between history and myth, and that Wagner's response to myth is dynamic and dialectical.[9] History per se might be arid and reductive but it contained within it the potential for a categorical interpretation allowing Wagner to make use of Leopold August Warnkönig's (1835–42), three volume Flandrische Staats- und Rechtsgeschichte bis zum Jahr 1305 to be mined for an accurate evocation of tenth century Brabant.[10] It would be nearly four years before Wagner's image of Lohengrin would again manifest itself to his creative imagination.

Writing retrospectively in his 1865 biography (even if its royal patronage diminishes its reliability), Wagner tells the story of how Lohengrin's libretto was written. In the summer of 1845 Wagner with his wife Minna planned their annual hydrotherapeutic visit to Marienbad. Putting his work as Kapellmeister at the Royal Dresden court out of his mind, Wagner's intention was to abandon himself to a life of the utmost leisure, and he had chosen his summer reading with care: the poems of Wolfram von Eschenbach, and the anonymous epic of Lohengrin with an introduction by Joseph von Görres. His plan to lie beside a brook communing with Titurel and Parzival didn't last long and the longing to create was overpowering:

Lohengrin stood suddenly revealed before me in full armor at the center of a comprehensive dramatic adaptation of the whole material. ... I struggled manfully against the temptation to set down the plan on paper. But I was fooling myself: no sooner had I stepped into the noonday bath than I was seized by such desire to write Lohengrin that, incapable of lingering in the bath for the prescribed hour, I leapt out after only a few minutes, scarcely took the time to clothe myself again properly, and ran like a madman to my quarters to put what was obsessing me on paper. This went on for several days, until the entire dramatic plan for Lohengrin had been set down in full detail.[11]

By 3 August 1845 he had worked out the prose draft. Wagner, with his head in a whirl, wrote to his brother, Albert, the following day, 4 August 1845:

...it was in this frame of mind yesterday that I finished writing out a very full & detailed scenario for Lohengrin; I am delighted with the result, indeed I freely admit that it fills me with a feeling of proud contentment. ... the more familiar I have become with my new subject & the more profoundly I have grasped its central idea, the more it has dawned upon me how rich & luxurious the seed of this new idea is, a seed which has grown into so full & burgeoning a flower that I feel happy indeed. ...In creating this work, my powers of invention & sense of formal structure have played their biggest part to date: the medieval poem which has preserved this highly poetical legend contains the most inadequate & pedestrian account to have come down to us, and I feel very fortunate to have satisfied my desire to rescue what by now is an almost unrecognizable legend from the rubble & decay to which the medieval poet has reduced the poem as a result of his inferior & prosaic treatment of it, & to have restored it to its rich & highly poetical potential by dint of my own inventiveness & reworking of it. – But quite apart from all this, how felicitous a libretto it has turned out to be! Effective, attractive, impressive & affecting in all its parts! – Johanna]'s role in it (Albert's daughter – see illustration below) – which is very important & in point of fact the principal role in the work – is bound to turn out the most charming & most moving in the world.[12]

Between May and June 1846, Wagner made a through-composed draft for the whole work that consisted of only two staves: one for the voice, the other just indicating the harmonies. Coterminously, Wagner began work on a second draft of the poem, beginning with Act III. The complete draft of Act III was completed before the second draft of Acts I and II. This has sometime led to the erroneous conclusion that the entire work was completed from the end to the front. On 9 September 1846 Wagner began to elaborate the instrumental and choral parts, which, along with the Prelude, was completed on 29 August 1847.[13]

Numerous changes to the poem, particularly Act III, took place during work on the second draft. At this time Wagner was still trying to clarify the precise nature of the tragedy, and the extent to which he needed to spell out the mechanics of the tragedy to the audience. On 30 May 1846 Wagner wrote to the journalist Hermann Franck regarding the relationship between Lohengrin and Elsa.[14] It is apparent from the letter that Wagner and Franck had been discussing Lohengrin for some time, and Wagner refers back to an earlier argument about the relationship between Lohengrin and Elsa, and in particular whether Elsa's punishment of separation from Lohengrin at the end of the opera is justifiable. Wagner uses the letter firstly to argue in favour of his version and secondly to expand upon the more general mythical structure underpinning the relationship between Lohengrin and Elsa – a theme he would publicly develop in his 1851 autobiographical essay A Communication To My Friends.[15] Elsa's punishment, Wagner argues, cannot be chastisement or death but that her separation from Lohengrin: 'this idea of separation- which, if it were left out, would require a total transformation of the subject and probably allow no more than its most superficial externals to be retained'.[16] Franck's concern appears to be that this particular punishment of separation will make the opera incapable 'of being dramatically effective in a unified way'.[17] Wagner confesses that Franck's concerns have forced him to look objectively at the poem and to consider ways of making Lohengrin's involvement in the tragic outcome clearer than had previously been the case. To this end, Wagner decided not to alter Act I or II but to write new lines in Act III:

O Elsa! Was hast du mir angethan?

Als meine Augen dich zuerst ersah'n,

zu dir fühlt' ich in Liebe mich entbrannt,

(Wagner wrote five additional lines here but they were rejected in the final draft).

Later, in the same act, when Elsa calls on Lohengrin to punish her, the latter replies:

Nur eine Strafe giebt's für dein Vergeh'n

ach, mich wie dich trifft ihre herbe Pein!

Getrennt, geschieden sollen wir uns seh'n

diess muss die Strafe, diess die Sühne sein!

Wagner asks Franck if he should explicitly mention the specific rule associated with the Grail which, although not expressly forbidding the Grail knights from committing such excesses, nevertheless, discourages them from acting in this way. Wagner's opinion is that it should be sufficient for the audience to deduce the Grail's advice.[16] Readers of the libretto in English will note that in Amanda Holden's 1990 singing translation for the English National Opera, the Grail's advice is transformed into an explicit commandment, with Holden acknowledging, on her website, that translating a libretto is effectively writing a new one "despite its compulsory faithfulness to the original".[18]

There's one atonement, penance for your crime!

Ah! I as you suffer this cruel pain!

We must be parted! You must understand:

this the atonement, this the Grail's command![19]

Having completed the second complete draft of Act III ten months later on 5 March 1847, Wagner returned to the beginning of Act I and began work on the second draft of Act I on 12 May and which was complete on 8 June 1847. The second complete draft of Act II was started on 18 June and complete on 2 August 1847. In a letter to Ferdinand Heine dated 6 August 1847, Wagner announced that he had completed the Lohengrin opera:

I feel pleased and happy as a result, since I am well satisfied with what I have done.

As outlined to Heine, Wagner's plan was to build on the success of the premiere of Rienzi in Berlin on 24 October 1847 with a follow-up performance of Lohengrin. As it turned out Rienzi in Berlin was not a success and Lohengrin was not performed there until 1859.[20]

Composition of the full score began three months later on 1 January 1848, and by 28 April 1848 the composition of Lohengrin was complete.[13] In September 1848 Wagner conducted excerpts from Act I at a concert in Dresden to mark the 300th anniversary of the court orchestra (later Dresden Staatskapelle).[21]

Musical style

Lohengrin occupies an ambiguous position within Wagner's aesthetic oeuvre. Despite Wagner's ostensible rejection of French grand opéra, Lohengrin, like all Wagner's operas, and for that matter his later musikdramas, owes some debt to the form as practised by Auber, Halévy and, irrespective of what Wagner sets out in his prose writings, Meyerbeer.[22] Lohengrin is also the last of Wagner's four "Romantic" operas,[23] and continues with the associative style of tonality that he had previously developed in Tannhäuser.[24] And Lohengrin is also the last of his composed works before his political exile, and despite the seventeen-year-long performance hiatus, Lohengrin's musical style nevertheless anticipates Wagner's future leitmotif technique.[25]

Performance history

The first production of Lohengrin was in Weimar, Germany, on 28 August 1850 at the Staatskapelle Weimar under the direction of Franz Liszt, a close friend and early supporter of Wagner. Liszt chose the date in honour of Weimar's most famous citizen, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who was born on 28 August 1749.[26] Despite the inadequacies of the lead tenor Karl Beck,[27] it was an immediate popular success.

Wagner himself was unable to attend the first performance, having been exiled because of his part in the 1849 May Uprising in Dresden. Although he conducted various extracts in concert in Zurich, London, Paris and Brussels, it was not until 1861 in Vienna that he was able to attend a full performance.[28]

The opera's first performance outside German-speaking lands was in Riga on 5 February 1855. The Austrian premiere took place in Vienna at the Theater am Kärntnertor on 19 August 1858, with Róza Csillag as Ortrud.[29] The work was produced in Munich for the first time at the National Theatre on 16 June 1867, with Heinrich Vogl in the title role and Mathilde Mallinger as Elsa. Mallinger also took the role of Elsa in the work's premiere at the Berlin State Opera on 6 April 1869.

Lohengrin's Russian premiere, outside Riga, took place at the Mariinsky Theatre on 16 October 1868.

The Belgian premiere of the opera was given at La Monnaie on 22 March 1870 with Étienne Troy as Friedrich von Telramund and Feliciano Pons as Heinrich der Vogler.[30]

The United States premiere of Lohengrin took place at the Stadt Theater at the Bowery in New York City on 3 April 1871.[31] Conducted by Adolf Neuendorff, the cast included Theodor Habelmann as Lohengrin, Luise Garay-Lichtmay as Elsa, Marie Frederici as Ortrud, Adolf Franosch as Heinrich and Edward Vierling as Telramund.[32] The first performance in Italy took place seven months later at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna on 1 November 1871 in an Italian translation by operatic baritone Salvatore Marchesi. It was notably the first performance of any Wagner opera in Italy. Angelo Mariani conducted the performance, which starred Italo Campanini as Lohengrin, Bianca Blume as Elsa, Maria Löwe Destin as Ortrud, Pietro Silenzi as Telramund, and Giuseppe Galvani as Heinrich der Vogler.[30] The performance on 9 November was attended by Giuseppe Verdi, who annotated a copy of the vocal score with his impressions and opinions of Wagner (this was almost certainly his first exposure to Wagner's music).[33]

La Scala produced the opera for the first time on 30 March 1873, with Campanini as Lohengrin, Gabrielle Krauss as Elsa, Philippine von Edelsberg as Ortrud, Victor Maurel as Friedrich, and Gian Pietro Milesi as Heinrich.[30]

The United Kingdom premiere of Lohengrin took place at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, on 8 May 1875 using the Italian translation by Marchesi. Auguste Vianesi conducted the performance, which featured Ernesto Nicolini as Lohengrin, Emma Albani as Elsa, Anna D'Angeri as Ortruda, Maurel as Friedrich, and Wladyslaw Seideman as Heinrich. The opera's first performance in Australia took place at the Prince of Wales Theatre in Melbourne on 18 August 1877. The Metropolitan Opera mounted the opera for the first time on 7 November 1883, in Italian, during the company's inaugural season. Campanini portrayed the title role with Christina Nilsson as Elsa, Emmy Fursch-Madi as Ortrud, Giuseppe Kaschmann as Telramund, Franco Novara as Heinrich, and Auguste Vianesi conducting.[30]

Lohengrin was first publicly performed in France at the Eden-Théâtre in Paris on 30 April 1887 in a French translation by Charles-Louis-Étienne Nuitter. Conducted by Charles Lamoureux, the performance starred Ernest van Dyck as the title hero, Fidès Devriès as Elsa, Marthe Duvivier as Ortrud, Emil Blauwaert as Telramund, and Félix-Adolphe Couturier as Heinrich. There was however an 1881 French performance given as a Benefit, in the Cercle de la Méditerranée Salon at Nice, organized by Sophie Cruvelli, in which she took the role of Elsa.[34] The opera received its Canadian premiere at the opera house in Vancouver on 9 February 1891 with Emma Juch as Elsa. The Palais Garnier staged the work for the first time the following 16 September with van Dyck as Lohengrin, Rose Caron as Elsa, Caroline Fiérens-Peters as Ortrud, Maurice Renaud as Telramund and Charles Douaillier as Heinrich.[30]

The first Chicago performance of the opera took place at the Auditorium Building (now part of Roosevelt University) on 9 November 1891. Performed in Italian, the production starred Jean de Reszke as the title hero, Emma Eames as Elsa and Édouard de Reszke as Heinrich.[30]

Lohengrin was first performed as part of the Bayreuth Festival in 1894, in a production directed by the composer's widow, Cosima Wagner, with Willi Birrenkoven and Ernst van Dyck, Emil Gerhäuser alternating as Lohengrin, Lillian Nordica as Elsa, Marie Brema as Ortrud and Demeter Popovic as Telramund and was conducted by Felix Mottl. It received 6 performances in its first season in the opera house that Wagner built for the presentation of his works.

A typical performance lasts from about 3 hours, 30–50 minutes.

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 28 August 1850 (Conductor: Franz Liszt) |

|---|---|---|

| Lohengrin | tenor | Karl Beck |

| Elsa von Brabant | soprano | Rosa von Milde |

| Ortrud, Telramund's wife | dramatic soprano or mezzosoprano | Josephine Fastlinger |

| Friedrich of Telramund, a Count of Brabant | baritone | Hans von Milde |

| Heinrich der Vogler (Henry the Fowler) | bass | August Höfer |

| The King's Herald | baritone | August Pätsch |

| Four Noblemen of Brabant | tenors, basses | |

| Four Pages | sopranos, altos | |

| Duke Gottfried, Elsa's brother | silent | Hellstedt |

| Saxon, Thuringian, and Brabantian counts and nobles, ladies of honor, pages, vassals, serfs | ||

Instrumentation

Lohengrin is scored for the following instruments:

- 3 flutes (3rd doubles piccolo), 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets in B-flat, A and C, bass clarinet in B-flat and A, 3 bassoons

- 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

- timpani, triangle, cymbals, tambourine

- harp

- 1st and 2nd violins, violas, violoncellos, and double basses

on-stage

Synopsis

- Place: Antwerp, on the Scheldt River, in the Duchy of Lotharingia

- Time: Sometime between 925, when Henry the Fowler acquired Lotharingia as a vassal state, and 933, when his wars with the Magyars ended

Summary

The people of the Brabant are divided by quarrels and political infighting; also, a devious hostile power left over from the region's pagan past is seeking to subvert the prevailing monotheistic government and to return Brabant to pagan rule. A mysterious knight, sent by God and possessing superhuman charisma and fighting ability, arrives to unite and strengthen the people, and to defend the innocent noblewoman Elsa from a false accusation of murder, but he imposes a condition: the people must follow him without knowing his identity. Elsa in particular must never ask his name, or his heritage, or his origin. The conspirators attempt to undermine her faith in her rescuer, to create doubt among the people, and to force him to leave.

Act 1

King Henry the Fowler has arrived in Brabant, where he has assembled the German tribes in order to expel the marauding Hungarians from his dominions. He also needs to settle a dispute involving the disappearance of the child-Duke Gottfried of Brabant. The Duke's guardian, Count Friedrich von Telramund, has accused the Duke's older sister, Elsa, of murdering her brother in order to become Duchess of Brabant. Telramund calls upon the King to punish Elsa and to make him the new Duke of Brabant.

The King calls for Elsa to answer Telramund's accusation. Elsa does not answer the King's inquiries, only lamenting her brother's fate ("Einsam in trüben Tagen"). The King declares that he cannot resolve the matter and will leave it to God's judgment through ordeal by combat. Telramund, a strong and seasoned warrior, agrees enthusiastically. When the King asks Elsa who shall be her champion, Elsa describes a knight she has beheld in her dreams ("Des Ritters will ich wahren").

Twice the Herald calls for a champion to step forward, but gets no response. Elsa kneels and prays that God may send her champion to her. A boat drawn by a swan appears on the river and in it stands a knight in shining armour. He disembarks, dismisses the swan, respectfully greets the king, and asks Elsa if she will have him as her champion and marry him. Elsa kneels in front of him and places her honour in his keeping. He asks only one thing in return for his service: Elsa must never ask him his name or where he has come from. Elsa agrees to this ("Wenn ich im Kampfe für dich siege").

Telramund's supporters advise him to withdraw because he cannot prevail against the Knight's powers, but he proudly refuses. The chorus prays to God for victory for the one whose cause is just. Ortrud, Telramund's wife, does not join the prayer, but privately expresses confidence that Telramund will win. The combat commences. The unknown Knight defeats Telramund but spares his life ("Durch Gottes Sieg ist jetzt dein Leben mein"). Taking Elsa by the hand, he declares her innocent. The crowd exits, cheering and celebrating.

Act 2

Night in the courtyard outside the cathedral

Telramund and Ortrud, banished from court, listen unhappily to the distant party-music. Ortrud reveals that she is a pagan witch (daughter of Radbod Duke of Frisia), and tries to revive Telramund's courage, assuring him that her people (and he) are destined to rule the kingdom again. She plots to induce Elsa to violate the mysterious knight's only condition.

When Elsa appears on the balcony before dawn, she hears Ortrud lamenting and pities her. As Elsa descends to open the castle door, Ortrud prays to her pagan gods, Wodan and Freia, for malice, guile, and cunning, in order to deceive Elsa and restore pagan rule to the region. Ortrud warns Elsa that since she knows nothing about her rescuer, he could leave at any time as suddenly as he came, but Elsa is sure of the Knight's virtues. The two women go into the castle. Left alone outside, Telramund vows to bring about the Knight's downfall.

The sun rises and the people assemble. The Herald announces that Telramund is now banished, and that anyone who follows Telramund shall be considered an outlaw by the law of the land. In addition, he announces that the King has offered to make the unnamed knight the Duke of Brabant; however, the Knight has declined the title, and prefers to be known only as "Protector of Brabant".[35] The Herald further announces that the Knight will lead the people to glorious new conquests, and will celebrate the marriage of himself and Elsa. In the back of the crowd, four noblemen quietly express misgivings to each other because the Knight has rescinded their privileges and is calling them to arms. Telramund secretly draws the four noblemen aside and assures them that he will regain his position and stop the Knight, by accusing him of sorcery.

As Elsa and her attendants are about to enter the church, Ortrud rushes to the front of the procession and challenges Elsa to explain who the Knight is and why anyone should follow him. Their conversation is interrupted by the entrance of the King with the Knight. Elsa tells both of them that Ortrud was interrupting the ceremony. The King tells Ortrud to step aside, then leads Elsa and the Knight toward the church. Just as they are about to enter the church, Telramund enters. He claims that his defeat in combat was invalid because the Knight did not give his name (trial by combat traditionally being open only to established citizens), then accuses the Knight of sorcery. He demands that the Knight must reveal his name; otherwise the King should rule the trial by combat invalid. The Knight refuses to reveal his identity and claims that only one person in the world has the right to make him do so: his beloved Elsa, and she has pledged not to exercise that right. Elsa, though visibly shaken and uncertain, assures him of her confidence. King Henry refuses Telramund's questions, and the nobles of Brabant and Saxony praise and honor the Knight. Elsa falls back into the crowd where Ortrud and Telramund try to intimidate her, but the Knight forces them both to leave the ceremony, and consoles Elsa. Elsa takes one last look at the banished Ortrud, then enters the church with the wedding procession.

Act 3

Scene 1: The bridal chamber

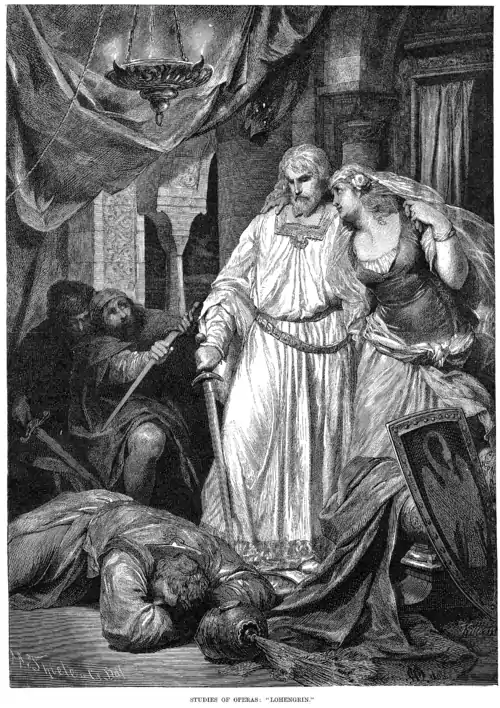

Elsa and her new husband are ushered in with the well-known bridal chorus, and they express their love for each other. Ortrud's words, however, have made an impression on Elsa; she laments that her name sounds so sweet on her husband's lips but she cannot utter his name. She asks him to tell her his name when no one else is around, but at all instances he refuses. Finally, despite his warnings, she asks the Knight the fatal questions. Before the Knight can answer, Telramund and his four recruits rush into the room in order to attack him. The Knight defeats and kills Telramund. Then, he sorrowfully turns to Elsa and asks her to follow him to the King, to whom he will now reveal his secrets.

Scene 2: On the banks of the Scheldt (as in act 1)

The troops arrive equipped for war. Telramund's corpse is brought in. Elsa comes forward, then the Knight. He tells the King that Elsa has broken her promise, and discloses his identity ("In fernem Land") by recounting the story of the Holy Grail and of Monsalvat. He reveals himself as Lohengrin, Knight of the Grail and son of King Parsifal, sent to protect an unjustly accused woman. The laws of the Holy Grail say that Knights of the Grail must remain anonymous. If their identity is revealed, they must return home.

As Lohengrin sadly bids farewell to Elsa, the swan-boat reappears. Lohengrin tells Elsa that if she had kept her promise, she could have recovered her lost brother, and gives her his sword, horn and ring, for he is to become the future leader of Brabant. As Lohengrin tries to get in the boat, Ortrud appears. She tells Elsa that the swan is actually Gottfried, Elsa's brother, whom she cursed to become a swan. The people consider Ortrud guilty of witchcraft. Lohengrin prays and the swan turns back into young Gottfried. Lohengrin declares him the Duke of Brabant. Ortrud sinks as she sees her plans thwarted.

A dove descends from heaven and, taking the place of the swan at the head of the boat, leads Lohengrin to the castle of the Holy Grail. A grief-stricken Elsa falls to the ground dead.[36]

Notable arias and excerpts

- Act I

- Prelude

- "Einsam in trüben Tagen" (Elsa's Narrative)

- Scene "Wenn ich im Kampfe für dich siege"

- Act II

- "Durch dich musst' ich verlieren" (Telramund)

- "Euch lüften, die mein Klagen" (Elsa)

- Scene 4 opening, "Elsa's Procession to the Cathedral"

- Act III

- Prelude

- Bridal Chorus "Treulich geführt"

- "Das süsse Lied verhallt" (Love duet)

- "Höchstes Vertrau'n" (Lohengrin's Declaration to Elsa)

- "In fernem Land" (Lohengrin's Narration)

- "Mein lieber Schwan... O Elsa! Nur ein Jahr an deiner Seite" (Lohengrin's Farewell)

Interpretations

Liszt initially requested Wagner to carefully translate his essay on the opera from French into German, that he might be the principal and long-standing interpreter of the work[37] – a work which, after performing, he regarded as "a sublime work from one end to the other".[38]

In their article "Elsa's reason: on beliefs and motives in Wagner's Lohengrin", Ilias Chrissochoidis and Steffen Huck propose what they describe as "a complex and psychologically more compelling account [of the opera]. Elsa asks the forbidden question because she needs to confirm Lohengrin's belief in her innocence, a belief that Ortrud successfully erodes in Act II. This interpretation reveals Elsa as a rational individual, upgrades the dramatic significance of the Act I combat scene, and, more broadly, signals a return to a hermeneutics of Wagnerian drama."[39]

Operatic mishaps

Tenors have sometimes run into trouble in the third act, just before Lohengrin departs by stepping on a swan-driven vessel or on the swan itself. In 1913, the Moravian tenor Leo Slezak is reported to have missed hopping on the swan, afterwards turning to Elsa with the question: "Wann geht der nächste Schwan?" ("When does the next swan leave?"). In 1936, at the Metropolitan Opera, the same thing happened to Danish tenor Lauritz Melchior.[40]

Recordings

References

- "Text from Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival, book XVI". bibliotheca Augustana. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Wagner 1993, p. 334.

- Millington 1992, p. 321.

- Spencer 2013, p. 70.

- Wagner 1992, Part One: 1813–41, p. 212.

- Wagner 1993, p. 312.

- Wagner 1992, Part One: 1813–41, p. 213.

- Spencer 2013, p. 68.

- Spencer 2013, pp. 71–72.

- Spencer 2013, p. 71n.30.

- Wagner 1992, Part Two: 1842–50, p. 303.

- Wagner 1987, Letter 70, p. 124.

- Millington 1992, p. 284.

- Wagner 1987, Letter 75, pp. 129–132.

- Wagner 1993, pp. 333–334.

- Wagner 1987, Letter 75, p. 129.

- Wagner 1987, Letter 75, p. 130.

- Holden, Amanda. "Lohengrin". Amanda Holden: Musician and Writer. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Wagner, Richard (2011). John, Nicholas (ed.). Lohengrin: ENO Guide. Translated by Holden, Amanda. London: Overture Publishing. p. 91.

- Wagner 1987, Letter 78, p. 138n.1.

- Carr, Jonathan (2008). The Wagner Clan. London: Faber and Faber. p. 10.

- Grey, Thomas S. (2011). "Wagner's Lohengrin: between grand opera and Musikdrama". In John, Nicholas (ed.). Lohengrin: ENO Guide 47. London: Overture Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7145-4448-9.

- Spencer 2013.

- Millington 1992, pp. 281, 284.

- Millington 1992, p. 285.

- Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed., 1954

- Wagner had written the Act III tenor monologue In fernem Land (the "Grail Narration") in two parts, however, he asked Liszt to cut the second part from the premiere performance, as he felt Karl Beck could not do it justice and it would result in an anticlimax. That unfortunate circumstance established the tradition of performing only the first part of the Narration.(see Peter Bassett, "An Introduction to Wagner's Lohengrin: A paper given to the Patrons and Friends of Opera Australia", Sydney 2001) Archived 10 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine) In fact, the first time the second part was ever sung at the Bayreuth Festival was by Franz Völker during the lavish 1936 production, which Adolf Hitler personally ordered and took a close interest in, to demonstrate what a connoisseur of Wagner he was. (see Opera-L Archives Archived 20 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine)

- Cesare Gertonani, writing in Teatro alla Scala programme for Lohengrin, December 2012, p. 90

- Playbill Archived 23 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Austrian National Library

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Performance history of Lohengrin". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- Gustav Kobbé, The Complete Opera Book (London: Putnam, 1929), p. 117. The first Academy performance was 23 March 1874 with Christina Nilsson, Cary, Italo Campanini and del Puente (ibid.). See "Wagner in the Bowery", Scribner's Monthly Magazine 1871, 214–216; The New York Times, Opera at the Stadt Theater Archived 23 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 3 May 1871

- The New York Times, "Wagner's Lohengrin" Archived 23 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 8 April 1871. See also Opera Gems.com, Lohengrin Archived 15 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "Istituto Nazionale di Studi Verdiani".

- Nice, muse et miroir d’inspiration musicale (in French) Nice, 6 October 2017

- The title Führer von Brabant is often altered to Schützer in performances since 1945, because the former title has acquired meanings unforeseen by Wagner. Führer formerly meant 'Leader' or 'Guide'.

- Plot taken from The Opera Goer's Complete Guide by Leo Melitz, 1921 version.

- Kramer, Lawrence (2002). "Contesting Wagner: The Lohengrin Prelude and Anti-anti-Semitism". 19th-Century Music. 25 (2–3): 193.

- Kramer 2002, p. 192.

- Chrissochoidis, Ilias and Huck, Steffen, "Elsa's reason: on beliefs and motives in Wagner's Lohengrin" Archived 22 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge Opera Journal, 22/1 (2010), pp. 65–91.

- Hugh Vickers, Great Operatic Disasters, St. Martin's Griffin, New York, 1979, p. 50. Walter Slezak, "Wann geht der nächste Schwann" dtv 1985.

Sources

- Millington, Barry (1992). "The Music". In Millington, Barry (ed.). The Wagner Compendium. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Spencer, Stewart (2013). "Part II: Opera, music, drama – 4. The "Romantic operas" and the turn to myth". In Grey, Thomas S. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Wagner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64439-6.

- Wagner, Richard (1987). Spencer, Stewart; Millington, Barry (eds.). Selected Letters of Richard Wagner with original texts of passages omitted from existing printed editions. Translated by Spencer, Stewart; Millington, Barry. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

- Wagner, Richard (1992). Whittall, Mary (ed.). My Life. Translated by Gray, Andrew. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80481-6.

- Wagner, Richard (1993). "A Communication to My Friends". The Art-Work of the Future and Other Works. Translated by Ellis, William Ashton. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9752-1.

External links

- Lohengrin: Wagner's autograph manuscript in the Richard Wagner Foundation

- Libretto and leitmotifs in German, Italian and English

- Richard Wagner – Lohengrin, gallery of historic postcards with motifs from Richard Wagner's operas

- Wagner's libretto (in German)

- Further Lohengrin discography

- Lohengrin: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- San Diego OperaTalk! with Nick Reveles: Lohengrin

- Portrait of the opera in the online opera guide www.opera-inside.com