Chapbook

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch.

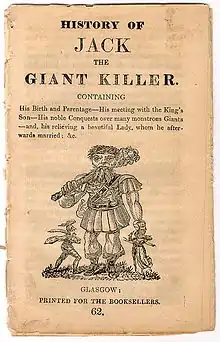

In early modern Europe a chapbook was a type of printed street literature. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were small, paper-covered booklets, usually printed on a single sheet folded into books of 8, 12, 16, or 24 pages. They were often illustrated with crude woodcuts, which sometimes bore no relation to the text (much like today's stock photos), and were often read aloud to an audience.[1] When illustrations were included in chapbooks, they were considered popular prints.

The tradition of chapbooks arose in the 16th century, as soon as printed books became affordable, and rose to its height during the 17th and 18th centuries. Many different kinds of ephemera and popular or folk literature were published as chapbooks, such as almanacs, children's literature, folk tales, ballads, nursery rhymes, pamphlets, poetry, and political and religious tracts.

The term "chapbook" for this type of literature was coined in the 19th century. The corresponding French term is bibliothèque bleue (blue library) because they were often wrapped in cheap blue paper that was usually reserved as a wrapping for sugar.[2] The German term is Volksbuch (people's book). In Spain, they were known as pliegos de cordel (cordel sheets).[3][4][5] In Spain, they were also known as pliegos sueltos, which translates to loose sheets, because they were literally loose sheets of paper folded once or twice in order to create a booklet in quarto format.[2] Lubok is the Russian equivalent of the chapbook.[6]

The term "chapbook" is also in use for present-day publications, commonly short, inexpensive booklets.[7]

Etymology

Chapbook is first attested in English in 1824, and seems to derive from the word for the itinerant salesmen who would sell such books: chapman. The first element of chapman comes in turn from Old English cēap ('barter, business, dealing')[8] from which the modern adjective cheap was subsequently derived.

History

Broadside ballads were popular songs, sold for a penny or halfpenny in the streets of towns and villages around Britain between the 16th and the early 20th centuries. They preceded chapbooks but had similar content, marketing, and distribution systems. There are records from Cambridgeshire as early as in 1553 of a man offering a scurrilous ballad "maistres mass" at an alehouse, and a pedlar selling "lytle books" to people, including a patcher of old clothes in 1578. These sales are probably characteristic of the market for chapbooks.

Chapbooks gradually disappeared from the mid-19th century in the face of competition from cheap newspapers and, especially in Scotland, from tract societies that regarded them as ungodly. Although the form originated in Britain, many were made in the U.S. during the same period.

Because of their flimsy nature such ephemera rarely survive as individual items. They were aimed at buyers without formal libraries and, in an era when paper was expensive, were used for wrapping or baking. Paper has also always had hygienic uses; there are contemporary references to the use of chapbooks as "bum fodder".[9] Many of the surviving chapbooks come from the collections of Samuel Pepys between 1661 and 1688 which are now held at Magdalene College, Cambridge. The antiquary Anthony Wood also collected 65 chapbooks, (including 20 from before 1660), which are now in the Bodleian Library. There are also significant Scottish collections, such as those held by the University of Glasgow[10] and the National Library of Scotland.[11]

Modern collectors, such as Peter Opie, have chiefly a scholarly interest in the form.[12][13] And modern small literary presses, such as Louffa Press, Black Lawrence Press and Ugly Duckling Presse, continue to issue several small editions of chapbooks a year, updated in technique and materials to often high fabrication standards, such as letterpress.

Production and distribution

Chapbooks were cheap, anonymous publications that were the usual reading material for lower-class people who could not afford books. Members of the upper classes occasionally owned chapbooks, perhaps bound in leather with a personal monogram. Printers typically tailored their texts for the popular market. Chapbooks were usually between four and twenty-four pages long, and produced on rough paper with crude, frequently recycled, woodcut illustrations. They sold in the millions.[14]

After 1696 English chapbook peddlers had to be licensed, and 2,500 of them were then authorized, 500 in London alone. In France, there were 3,500 licensed colporteurs by 1848, and they sold 40 million books annually.[14]

The centre of the chapbook and ballad production was London, and until the Great Fire of London (1666) the printers were based around London Bridge. However, a feature of chapbooks is the proliferation of provincial printers, especially in Scotland and Newcastle upon Tyne.[15] The first Scottish publication was the tale of Tom Thumb, in 1682.[1]

Content

Chapbooks were an important medium for the dissemination of popular culture to the common people, especially in rural areas. They were a medium of entertainment, information and (generally unreliable) history. In general, the content of chapbooks has been criticized, though, for their unsophisticated narratives which were heavily loaded with repetition and emphasized adventure through mostly anecdotal structures.[16] They are nonetheless valued as a record of popular culture, preserving cultural artifacts that may not survive in any other form.

Chapbooks were priced for sales to workers, although their market was not limited to the working classes. Broadside ballads were sold for a halfpenny, or a few pence. Prices of chapbooks were from 2d. to 6d., when agricultural labourers' wages were 12d. per day. The literacy rate in England in the 1640s was around 30 percent for males and rose to 60 percent in the mid-18th century (see Education in the Age of Enlightenment). Many working people were readers, if not writers, and pre-industrial working patterns provided periods during which they could read. Chapbooks were undoubtedly used for reading to family groups or groups in alehouses.

They even contributed to the development of literacy. The author and publisher Francis Kirkman wrote about how they fired his imagination and his love of books. There is other evidence of their use by autodidacts.

Nevertheless, the numbers printed are astonishing. In the 1660s as many as 400,000 almanacs were printed annually, enough for one family in three in England. One 17th-century publisher of chapbooks in London stocked one book for every 15 families in the country. In the 1520s the Oxford bookseller John Dorne noted in his day-book selling up to 190 ballads a day at a halfpenny each. The probate inventory of the stock of Charles Tias, of The sign of the Three Bibles on London Bridge, in 1664 included books and printed sheets to make approximately 90,000 chapbooks (including 400 reams of paper) and 37,500 ballad sheets. Tias was not regarded as an outstanding figure in the trade. The inventory of Josiah Blare, of The Sign of the Looking Glass on London Bridge, in 1707 listed 31,000 books, plus 257 reams of printed sheets. A conservative estimate of their sales in Scotland alone in the second half of the 18th century was over 200,000 per year.

These printers provided chapbooks to chapmen on credit, who carried them around the country, selling from door to door, at markets and fairs, and returning to pay for the stock they sold. This facilitated wide distribution and large sales with minimum outlay, and also provided the printers with feedback about what titles were most popular. Popular works were reprinted, pirated, edited, and produced in different editions. Francis Kirkman, whose eye was always on the market, wrote two sequels to the popular Don Bellianus of Greece, first printed in 1598.

Publishers also issued catalogues, and chapbooks are found in the libraries of provincial yeomen and gentlemen. John Whiting, a Quaker yeoman imprisoned at Ilchester, Somerset, in the 1680s had books sent by carrier from London, and left for him at an inn.

Pepys had a collection of ballads bound into volumes, under the following classifications, into which could fit the subject matter of most chapbooks:

- Devotion and Morality

- History – true and fabulous

- Tragedy: viz. Murders, executions, and judgments of God

- State and Times

- Love – pleasant

- Ditto – unpleasant

- Marriage, Cuckoldry, &c.

- Sea – love, gallantry & actions

- Drinking and good fellowship

- Humour, frollicks and mixt.

The stories in many of the popular chapbooks can be traced back to much earlier origins. Bevis of Hampton was an Anglo-Norman romance of the 13th century, which probably drew on earlier themes. The structure of The Seven Sages of Rome was from the orient, and was used by Chaucer. Many jests about ignorant and greedy clergy in chapbooks were taken from The Friar and the Boy printed about 1500 by Wynkyn de Worde, and The Sackfull of News (1557).

Historical stories set in a mythical and fantastical past were popular. The selection is interesting. Charles I, and Oliver Cromwell do not appear as historical figures in the Pepys collection, and Elizabeth I only once. The Wars of the Roses and the English Civil War do not appear at all. Henry VIII and Henry II appear in disguise, standing up for the right with cobblers and millers and then inviting them to Court and rewarding them. There was a pattern of high born heroes overcoming reduced circumstances by valour, such as St George, Guy of Warwick, Robin Hood (who at this stage has yet to give to the poor what he was stealing from the rich), and heroes of low birth who achieve status through force of arms, such as Clim of Clough, and William of Cloudesley. Clergy often appear as figures of fun, and stupid countrymen were also popular (e.g., The Wise Men of Gotham). Other works were aimed at regional and rural audience (e.g., The Country Mouse and the Town Mouse).

From 1597 works appeared aimed at specific trades, such as clothiers, weavers and shoemakers. The latter were commonly literate. Thomas Deloney, a weaver, wrote Thomas of Reading, about six clothiers from Reading, Gloucester, Worcester, Exeter, Salisbury and Southampton, traveling together and meeting at Basingstoke their fellows from Kendal, Manchester and Halifax. In his, Jack of Newbury, 1600, set in Henry VIII's time, an apprentice to a broadcloth weaver takes over his business and marries his widow on his death. On achieving success, he is liberal to the poor and refuses a knighthood for his substantial services to the king.

Other examples from the Pepys collection include The Countryman's Counsellor, or Everyman his own Lawyer, and Sports and Pastimes, written for schoolboys, including magic tricks, like how to "fetch a shilling out of a handkerchief", write invisibly, make roses out of paper, snare wild duck, and make a maid-servant fart uncontrollably.

The provinces and Scotland had their own local heroes. Robert Burns commented that one of the first two books he read in private was "the history of Sir William Wallace ... poured a Scottish prejudice in my veins which will boil along there till the flood-gates of life shut in eternal rest".

Influence

They had a wide and continuing influence. Eighty percent of English folk songs collected by early-20th-century collectors have been linked to printed broadsides, including over 90 of which could only be derived from those printed before 1700. It has been suggested the majority of surviving ballads can be traced to 1550–1600 by internal evidence.

One of the most popular and influential chapbooks was Richard Johnson's Seven Champions of Christendom (1596), believed to be the source for the introduction of the character St George into English folk plays.

Robert Greene's novel Dorastus and Fawnia (originally Pandosto) (1588), the basis of Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale, was still being published in cheap editions in the 1680s. Some stories were still being published in the 19th century, (e.g., Jack of Newbury, Friar Bacon, Dr Faustus and The Seven Champions of Christendom).

Modern chapbooks

Chapbook is also a term currently used to denote publications of up to about 40 pages, usually poetry bound with some form of saddle stitch, though many are perfect bound, folded, or wrapped. These publications range from low-cost productions to finely produced, hand-made editions that may sell to collectors for hundreds of dollars. More recently, the popularity of fiction and nonfiction chapbooks has also increased. In the UK they are more often referred to as pamphlets.

The genre has been revitalized in the past 40 years by the widespread availability of first mimeograph technology, then low-cost copy centers and digital printing, and by the cultural revolutions spurred by both zines and poetry slams, the latter generating hundreds upon hundreds of self-published chapbooks that are used to fund tours. In New York, a joint effort of the Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center, CUNY and their sponsors has come up with the NYC/CUNY Chapbook festival where, as it states in their about page, “The NYC/CUNY Chapbook Festival celebrates the chapbook as a work of art, and as a medium for alternative and emerging writers and publishers… the festival features a day-long bookfair with chapbook publishers from around the country, workshops, panels, a chapbook exhibition, and a reading of prize-winning Chapbook Fellows.”[17]

With the recent popularity of blogs, online literary journals, and other online publishers, short collections of poetry published online are frequently referred to as "online chapbooks", "electronic chapbooks", "e-chapbooks", or "e-chaps".

Stephen King wrote a few parts of an early draft of The Plant and sent them out as chapbooks to his friends instead of Christmas cards in 1982, 1983, and 1985. "Philtrum Press produced just three installments before the story was shelved, and the original editions have been hotly sought-after collector's items."[18]

In 2019, three different publishers (New York Review Books, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and Celadon Books) used chapbooks as a marketing tool. They took excerpts of longer works, turned them into chapbooks, and sent them to booksellers and other literary tastemakers to generate interest in the upcoming publications.[19]

Chapbook collections

- The National Library of Scotland[20] holds a large collection of Scottish chapbooks; approximately 4,000 of an estimated total of 15,000 published – including several in Lowland Scots and Gaelic.[1] Records for most Scottish chapbooks have been catalogued online. Approximately 3,000 of these have been digitised and can be accessed from the Library's Digital Gallery. A project is underway to add every Chapbook in the collection to Wikisource at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Wikisource:WikiProject_NLS.

- The Glasgow University Library[21] has over 1,000 examples throughout the collections, searchable online via the Scottish Chapbooks Catalogue of c. 4,000 works, which covers the Lauriston Castle collection, Edinburgh City libraries and Stirling University. The University of South Carolina's G. Ross Roy Collection is collaborating in research for the Scottish Chapbook Project.

- The Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford[22] has over 30,000 ballads in several major collections. The original printed materials range from the 16th to the 20th century. The Broadside Ballads project makes the digitised copies of the sheets and ballads available.

- Sir Frederick Madden's Collection of Broadside Ballads, at Cambridge University Library,[23] is possibly the largest collection from London and provincial presses between 1775 and 1850, with earlier 18th-century garlands and Irish volumes.

- The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Chapbook Collection[24] has 1,900 chapbooks from England, Scotland, Ireland, France, and the United States, which were part of the Elisabeth W. Ball collection. Online search facility

- The Elizabeth Nesbitt Room, University of Pittsburgh[25] houses over 270 chapbooks printed in both England and America between the years 1650 to 1850 (a few Scottish chapbooks are included as well). Title list, bibliographic information and digital images of chapbook covers

- Rutgers University, Special Collections and University Archives[26] houses the Harry Bischoff Weiss collection of 18th- and 19th-century chapbooks, illustrated with catchpenny prints.

- The John Rylands University Library (JRUL), University of Manchester[27] contains 600 items in The Sharpe Collection of Chapbooks, formed by Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe. These are 19th-century items printed in Scotland and Newcastle upon Tyne.

- Literatura de Cordel Brazilian Chapbook Collection Library of Congress, American Folklife Center[28] has a collection of over 7200 chapbooks (literatura de cordel). Descended from the medieval troubadour and chapbook tradition of European literatura de cordel has been published in Brazil for over a century.

- The University of Guelph Library, Archival and Special Collections,[29] has a collection of more than 550 chapbooks in its extensive Scottish holdings.

- The National Art Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, London[30] has a collection of c. 800 chapbooks, all catalogued.

- The McGill University Library[31] has over 900 British and American chapbooks published in the 18th and 19th centuries. The chapbooks have been digitized and can be read online.

- The Grupo de investigación sobre relaciones de sucesos (siglos XVI–XVIII) en la Península Ibérica, Universidade da Coruña[32] Catalog and Digital Library of "Relaciones de sucesos" (16th–18th centuries). Bibliographical database of more than 5,000 chap-books, pamphlets, Early modern press news, etc. Facsimilar reproduction of many of the copies: Catálogo y Biblioteca Digital de Relaciones de Sucesos (siglos XVI–XVIII)

- The Ball State University Digital Media Repository Chapbooks collection[33] provides online access to 173 chapbooks from the 19th and 20th centuries.

- The Elizabeth Nesbitt Room, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh Pennsylvania[34]

- Cambridge Digital Library[35] hosts a growing number of digital facsimiles of Spanish Chapbooks from the collections of Cambridge University Library and the British Library.

- Digitized collection of chapbooks[36] of the Biblioteca Nacional de España (National Library of Spain)

- The project Untangling the cordel offers a collection of almost 1000 pliegos de cordel, the Spanish equivalent of English chapbooks, kept at the University Library of the University of Geneva.[37]

- Mapping Pliegos is a portal dedicated to 19th-century Spanish chapbook literature. It brings together the digitised collections of over a dozen partner libraries.

- Ball State University University Libraries[38] offers a LibGuide on Chapbooks and Children's Literature with many resources.

References

- Hagan, Dr. Anette (August 2019). "Chapbooks: the poor person's reading material". Europeana (CC By-SA). Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. 121.

- From chapmen, chap, a variety of peddler, which folks circulated such literature as part of their stock.

- Spufford, Margaret (1984). The Great Reclothing of Rural England. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0-907628-47-8.

- Leitch, R. (1990). "'Here Chapman Billies Take Their Stand': A Pilot Study of Scottish Chapmen, Packmen and Pedlars". Proceedings of the Scottish Society of Antiquarians 120: 173–188.

- Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. 158.

- "Chapbooks: Definition and Origins". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.vv. chap-book, n. and chapman, n..

- Spufford, Margaret (1985). Small books and pleasant histories: popular fiction and its readership in seventeenth-century England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-521-31218-9. OCLC 13762165.

- "University of Glasgow: Scottish Chapbooks". special.lib.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- "Chapbooks - Rare Book Collections - National Library of Scotland - National Library of Scotland". www.nls.uk. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- "The Working Papers of Iona and Peter Opie" Julia C. Bishop Archived 2019-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, http://admin.oral-tradition.chs.orphe.us Archived 2019-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, February 28, 2013

- "The lives and legacies of Iona and Peter Opie", http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk

- Lyons, Martyn. (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles, CA. Getty Publications. (pp.121-122).

- See the "Introduction" in Simons, John (1998) Guy of Warwick and other Chapbook Romances University of Exeter Press, Exeter, England, ISBN 0-85989-445-2, for issues of definition.

- Hoeveler, D.L. (2010). "Gothic Chapbooks and the Urban Reader". Wordsworth Circle. 41 (3): 155–158. doi:10.1086/TWC24043706. S2CID 53571972.

- "NYC/CUNY Chapbook Festival". Archived from the original on 2017-09-17. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- "Stephen King | The Plant: Zenith Rising". stephenking.com. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- Maher, John (2019-05-10). "Publishers Turn to Chapbooks to Create Buzz". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- "Chapbooks – Rare Book Collections – National Library of Scotland – National Library of Scotland". www.nls.uk. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "University of Glasgow – MyGlasgow – Special collections – Introduction to our Collections". www.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Bodleian Library Broadside Ballads". Archived from the original on 2004-04-04. Retrieved 2006-01-07.

- "Publisher's Introduction: Madden Ballads From Cambridge University Library". microformguides.gale.com. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Chapbook Collection Guide: Special databases: The Collections: The Lilly Library: Indiana University Bloomington". www.indiana.edu. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Elizabeth Nesbitt Room Chapbook Collection". December 19, 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-12-19. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Rutgers University Libraries: Special Collections and University Archives". www.libraries.rutgers.edu. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Sharpe Chapbook Collection". rylibweb.man.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 7 October 1999. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- "2005 Junior Fellows Program Projects (Junior Fellows Program, Library of Congress)". Library of Congress. January 13, 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-01-13. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "UG Library: Scottish chapbook collection". December 31, 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-12-31. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Search Victoria and Albert Museum". nal-vam.on.worldcat.org. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "McGill Library's Chapbook Collection - Home".

- "Relaciones de Sucesos". September 18, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-09-18. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "CONTENTdm". dmr.bsu.edu. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "The Elizabeth Nesbitt Room: A Goodly Heritage". September 27, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Spanish Chapbooks". cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Search results – Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (BDH)". bdh.bne.es. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- Carta, Constance; Leblanc, Elina (2021-05-10). "Le projet « Démêler le cordel » : une bibliothèque numérique pour l'étude de la littérature éphémère espagnole du XIX e siècle" (in French).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - https://bsu.libguides.com/c.php?g=41273&p=263028

- The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. "The Scottish Chapbook Project". University of South Carolina G. Ross Roy Collection.

- Furnivall, F. J., ed. (1871). Captain Cox, His Ballads and Books.

- Neuburg, Victor E. (1972). Chapbooks: A guide to reference material on English, Scottish and American chapbook literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (2nd ed.). London: Woburn Press.

- Neuburg, Victor E. (1968). The penny histories: a study of chapbooks for young readers over two centuries (illustrated with facsimiles of seven chapbooks). London: Oxford University Press (The Juvenile Library.

- Neuburg, Victor E. (1964). Chapbooks: a bibliography of references to English and American chapbook literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. London: Vine Press.

- Neuburg, Victor E. (1952). A select handlist of references to chapbook literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Edinburgh: privately printed by J. A. Birkbeck.

- Spufford, Margaret (1981). Small Books and Pleasant Histories: Popular Fiction and its Readership in seventeenth Century England. Methuen.

- Weiss, Harry B. (1969). A book about chapbooks. Hatboro: Folklore Associates.

- Weiss, Harry B. (1936). A catalogue of chapbooks in the New York Public Library. New York: New York Public Library.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Chapbooks with Scottish imprint from 1790-1890 Collection at University of Stirling Archives