Thomas Jefferson

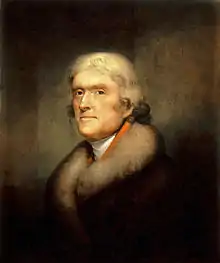

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743[lower-alpha 2] – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809.[6] Among the Committee of Five charged by the Second Continental Congress with drafting the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was the document's primary author. Following the American Revolutionary War and prior to becoming president in 1801, Jefferson was the first U.S. secretary of state under George Washington and then the nation's second vice president under John Adams.

Thomas Jefferson | |

|---|---|

(cropped).jpg.webp) Portrait by Rembrandt Peale, 1800 | |

| 3rd President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| 2nd Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801 | |

| President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | Aaron Burr |

| 1st United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 22, 1790 – December 31, 1793 | |

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | John Jay (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Edmund Randolph |

| 2nd United States Minister to France | |

| In office May 17, 1785 – September 26, 1789 | |

| Appointed by | Confederation Congress |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Franklin |

| Succeeded by | William Short |

| Minister Plenipotentiary for Negotiating Treaties of Amity and Commerce | |

| In office May 7, 1784 – May 11, 1786 | |

| Appointed by | Confederation Congress |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Delegate from Virginia to the Congress of the Confederation | |

| In office June 6, 1782 – May 7, 1784 | |

| Preceded by | James Madison |

| Succeeded by | Richard Lee |

| 2nd Governor of Virginia | |

| In office June 1, 1779 – June 3, 1781 | |

| Preceded by | Patrick Henry |

| Succeeded by | William Fleming |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Albemarle County[1] | |

| In office October 7, 1776 – May 30, 1779 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Lewis |

| Succeeded by | Nicholas Lewis |

| In office December 10, 1781 – December 22, 1781 | |

| Preceded by | Isaac Davis |

| Succeeded by | James Marks |

| Delegate from Virginia to the Continental Congress | |

| In office June 20, 1775 – September 26, 1776 | |

| Preceded by | George Washington |

| Succeeded by | John Harvie |

| Constituency | Second Continental Congress |

| Member of the Virginia House of Burgesses | |

| In office May 11, 1769[2] – June 1, 1775[3] | |

| Preceded by | Edward Carter[3] |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Constituency | Albemarle County |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 13, 1743 Shadwell, Virginia, British America |

| Died | July 4, 1826 (aged 83) Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Monticello, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | College of William & Mary |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

Philosophy career | |

| Notable work |

|

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | |

| School | |

| Institutions | American Philosophical Society |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | |

Jefferson's writings and advocacy for human rights, including freedom of thought, speech and religion, helped inspire the American Revolution, which ultimately led the successful American Revolutionary War. This in turn led to American independence, the Constitution of the United States, and the establishment of the United States as a free and sovereign nation.[7] He was a leading proponent of democracy, republicanism, and individual rights, and produced formative documents and decisions at the state, national and international levels. During the American Revolution, Jefferson represented Virginia at the Second Continental Congress, which adopted the Declaration of Independence, and served as the second governor of Virginia from 1779 to 1781. In 1785, Congress appointed Jefferson U.S. minister to France, where he served from 1785 to 1789. President Washington then appointed Jefferson the nation's first secretary of state, where he served from 1790 to 1793. During this time, in the early 1790s, Jefferson and James Madison organized the Democratic-Republican Party to oppose the Federalist Party during the formation of the nation's First Party System. With Madison, Jefferson anonymously wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions in 1798 and 1799, which sought to strengthen states' rights by nullifying the federal Alien and Sedition Acts.

Jefferson and Federalist John Adams became both friends and political rivals, serving in the Continental Congress and drafting the Declaration of Independence together. In the 1796 U.S. presidential election between the two, Jefferson came in second, which according to electoral procedure at the time made him Adams' vice president. Jefferson challenged Adams again four years later, in 1800, and won the presidency. In 1804, Jefferson was overwhelmingly reelected to a second term as president. While then constitutionally eligible to run for a third term, Jefferson followed Washington's precedent of limiting his presidency to two terms. Jefferson eventually reconciled with Adams, and the two shared a correspondence that lasted 14 years. He and Adams both died within hours of each other on the same day, July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

As president, Jefferson pursued the nation's shipping and trade interests against Barbary pirates and aggressive British trade policies. Beginning in 1803, he promoted a western expansionist policy with the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the nation's claimed land area. To make room for settlement, Jefferson began the process of Indian tribal removal from the newly acquired territory. As a result of peace negotiations with France, his administration was able to reduce military forces and expenditures. Jefferson's second term as president was beset by difficulties at home, including the trial of former vice president Aaron Burr. In 1807, American foreign trade was diminished when Jefferson implemented the Embargo Act in response to British threats to U.S. shipping.

Jefferson was a slave owner, but also condemned the slave trade in his draft of the Declaration of Independence and signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves in 1807. Since the 1790s, he was rumored to have had children by his slave Sally Hemings. According to scholarly consensus, Jefferson probably fathered at least six children with Hemings, including four that survived to adulthood.[8][9][10]

After retiring from public office, Jefferson founded the University of Virginia. Presidential scholars and historians generally praise Jefferson's public achievements, including his advocacy of religious freedom and tolerance, his peaceful acquisition of the Louisiana Territory from France, and the successful Lewis and Clark Expedition. Jefferson is consistently ranked among the top ten presidents in American history, though his relationship with slavery continues to be debated.

Early life and career

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743 (April 2, 1743, Old Style, Julian calendar), at the family's Shadwell Plantation in the British Colony of Virginia, the third of ten children.[11] He was of English, and possibly Welsh, descent and was born a British subject.[12] His father, Peter Jefferson, was a planter and surveyor who died when Jefferson was fourteen; his mother was Jane Randolph.[lower-alpha 3] Peter Jefferson moved his family to Tuckahoe Plantation in 1745 upon the death of William Randolph III, the plantation's owner and Jefferson's friend, who in his will had named Peter guardian of Randolph's children. The Jeffersons returned to Shadwell in 1752. In 1753, Thomas attended the wedding of his uncle Field Jefferson to Mary Allen Hunt, and Field became a close friend and early mentor.[14]

Jefferson's father Peter died in 1757, and his estate was divided between his sons Thomas and Randolph.[15] John Harvie Sr. then became 13-year-old Thomas' guardian.[16] Thomas inherited approximately 5,000 acres (2,000 ha; 7.8 sq mi) of land, which included Monticello, and he assumed full legal authority over the property at age 21.[17]

Education and early family life

Jefferson began his education together with the Randolph children at Tuckahoe under the guidance of tutors.[18] Thomas' father Peter, who was self-taught and regretted not having a formal education, entered Thomas into an English school at age five. In 1752, at age nine, he attended a local school run by a Scottish Presbyterian minister and also began studying the natural world, which he grew to love. At this time he began studying Latin, Greek, and French, while learning to ride horses as well. Thomas also read books from his father's modest library.[19] He was taught from 1758 to 1760 by the Reverend James Maury near Gordonsville, Virginia, where he studied history, science, and the classics while boarding with Maury's family.[20][19] Jefferson then befriended and came to know various American Indians, including the well known Cherokee chief Ostenaco, who often stopped at Shadwell to visit on their way to Williamsburg to trade.[21][22] During the two years Jefferson was with the Maury family, he traveled to Williamsburg and was a guest of Colonel John Dandridge, father of Martha Washington. In Williamsburg, the young Jefferson met and came to admire Patrick Henry, eight years his senior, and shared a common interest in violin playing.[23]

Jefferson entered the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1761 at age 16 and studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy with William Small. Under Small's tutelage, Jefferson encountered the ideas of the British Empiricists, including John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton. Small introduced Jefferson to George Wythe and Francis Fauquier. Small, Wythe, and Fauquier recognized Jefferson as a man of exceptional ability and included him in their inner circle, where he became a regular member of their Friday dinner parties where politics and philosophy were discussed. Jefferson later wrote that, while there, he "heard more common good sense, more rational & philosophical conversations than in all the rest of my life".[24]

During his first year at the college, Jefferson spent a considerable amount of time attending parties and dancing and was not very frugal with his expenditures; in his second year, regretting that he felt he had squandered away time and money in his first year, he committed to studying fifteen hours a day.[25] While at William & Mary, Jefferson became a member of the Flat Hat Club, founded in 1750, and one of the nation's first secret societies still operating in the 21st century.

Jefferson improved his French and Greek and his skill at the violin. He graduated two years after starting, in 1762. He read the law under Wythe's tutelage to obtain his law license while working as a law clerk in his office.[26] He also read a wide variety of English classics and political works.[27] Jefferson was well-read in a broad variety of subjects, which, along with law and philosophy, included history, natural law, natural religion, ethics, and several areas in science, including agriculture. Overall, he drew very deeply on the philosophers. During the years of study under the watchful eye of Wythe, Jefferson authored a survey of his extensive readings in his Commonplace Book.[28] Wythe was so impressed with Jefferson that he later bequeathed his entire library to him.[29]

In July 1765, Jefferson's sister Martha married his close friend and college companion Dabney Carr, which was greatly pleasing to Jefferson. In October of that year, however, Jefferson mourned his sister Jane's unexpected death at age 25; he wrote a farewell epitaph for her in Latin.[30]

Jefferson treasured his books and amassed three sizable libraries in his lifetime. He began assembling his first library, which grew to 200 volumes, in his youth. It included books inherited from his father and left to him by George Wythe,[31] but was destroyed when his Shadwell home burned in a 1770 fire. His second library, however, replenished the first. It grew to 1,250 titles by 1773, and to nearly 6,500 volumes by 1814.[32] Jefferson organized his wide variety of books into three broad categories corresponding with elements of the human mind: memory, reason, and imagination.[33] After British forces burnt the Library of Congress during the August 1814 Burning of Washington, Jefferson sold his second library to the U.S. government for $23,950, hoping to help jumpstart the Library of Congress' collection and rebuilding. Jefferson used a portion of the proceeds to pay off some of his large debt, remitting $10,500 to William Short and $4,870 to John Barnes of Georgetown. However, Jefferson soon resumed collecting what amounted to his third personal library, writing to John Adams, "I cannot live without books."[34][35] He began to construct his third library with many of his personal favorites. By the time of his death a decade later, the library had grown to nearly 2,000 volumes.[36]

Lawyer and House of Burgesses

Jefferson was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1767, and lived with his mother at Shadwell.[37] He represented Albemarle County as a delegate in the Virginia House of Burgesses from 1769 until 1775.[38] He pursued reforms to slavery, including writing and sponsoring legislation in 1769 to strip power away from the royal governor and courts, instead providing masters of slaves with the discretion to emancipate them. Jefferson persuaded his cousin Richard Bland to spearhead the legislation's passage, but it faced strong opposition in a state whose economy was largely agrarian.[39]

Jefferson also took seven cases of freedom-seeking slaves[40] and waived his fee for one he claimed should be freed before the minimum statutory age for emancipation.[41] Jefferson invoked natural law, arguing "everyone comes into the world with a right to his own person and using it at his own will ... This is what is called personal liberty, and is given him by the author of nature, because it is necessary for his own sustenance." The judge cut him off and ruled against his client. As a consolation, Jefferson gave his client some money, which was conceivably used to aid his escape shortly thereafter.[41] However, Jefferson's underlying intellectual argument that all people were entitled by their creator to what he labeled a "natural right" to liberty is one he would later incorporate as he set about authoring the Declaration of Independence.[42] He also took on 68 cases for the General Court of Virginia in 1767, in addition to three notable cases: Howell v. Netherland (1770), Bolling v. Bolling (1771), and Blair v. Blair (1772).[43]

Jefferson wrote a resolution calling for a "Day of Fasting and Prayer" and a boycott of all British goods in protest of the British Parliament passing the Intolerable Acts in 1774. Jefferson's resolution was later expanded into A Summary View of the Rights of British America, in which he argued that people have the right to govern themselves.[44]

Monticello, marriage, and family

In 1768, Jefferson began constructing his primary residence, Monticello, whose name in Italian means "Little Mountain", on a hilltop overlooking his 5,000-acre (20 km2; 7.8 sq mi) plantation.[lower-alpha 4] He spent most of his adult life designing Monticello as architect and was quoted as saying, "Architecture is my delight, and putting up, and pulling down, one of my favorite amusements."[46] Construction was done mostly by local masons and carpenters, assisted by Jefferson's slaves.[47] He moved into the South Pavilion in 1770. Turning Monticello into a neoclassical masterpiece in the Palladian style was his perennial project.[48]

On January 1, 1772, Jefferson married his third cousin[49] Martha Wayles Skelton, the 23-year-old widow of Bathurst Skelton, and she moved into the South Pavilion.[50][51] She was a frequent hostess for Jefferson and managed the large household. Biographer Dumas Malone described the marriage as the happiest period of Jefferson's life.[52] Martha read widely, did fine needlework, and was a skilled pianist; Jefferson often accompanied her on the violin or cello.[53] During their ten years of marriage, Martha bore six children: Martha "Patsy" (1772–1836); Jane (1774–1775); an unnamed son who lived for only a few weeks in 1777; Mary "Polly" (1778–1804); Lucy Elizabeth (1780–1781); and another Lucy Elizabeth (1782–1784).[54][lower-alpha 5] Only Martha and Mary survived to adulthood.[57] Martha's father John Wayles died in 1773, and the couple inherited 135 slaves, 11,000 acres (45 km2; 17 sq mi), and the estate's debts. The debts took Jefferson years to satisfy, contributing to his financial problems.[50]

Martha later suffered from ill health, including diabetes, and frequent childbirth further weakened her. Her mother had died young, and Martha lived with two stepmothers as a girl. A few months after the birth of her last child, she died on September 6, 1782, with Jefferson at her bedside. Shortly before her death, Martha made Jefferson promise never to marry again, telling him that she could not bear to have another mother raise her children.[58] Jefferson was grief-stricken by her death, relentlessly pacing back and forth, nearly to the point of exhaustion. He emerged after three weeks, taking long rambling rides on secluded roads with his daughter Martha, by her description "a solitary witness to many a violent burst of grief".[57][59]

After serving as U.S. Secretary of State from 1790 to 1793 during Washington's presidency, Jefferson returned to Monticello and initiated a remodeling based on the architectural concepts, which he had learned and acquired in Europe. The work continued throughout most of his presidency and was completed in 1809.[60][61]

Revolutionary War

Declaration of Independence

Jefferson was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence.[62] At age 33, he was one of the youngest delegates to the Second Continental Congress beginning in 1775 at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, where a formal declaration of independence from Britain was overwhelmingly favored.[63] Jefferson was inspired by the Enlightenment ideals of the sanctity of the individual, and the writings of Locke and Montesquieu.[64]

Jefferson sought out John Adams, a Continental Congress delegate from Massachusetts and an emerging leader in the Congress.[65] They became close friends, and Adams supported Jefferson's appointment to the Committee of Five, which was charged by the Congress with authoring a declaration of independence. The five included Adams, Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin from Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston from New York, and Roger Sherman from Connecticut. The committee initially thought that Adams should write the document, but Adams persuaded the committee to choose Jefferson.[lower-alpha 6]

Jefferson consulted with his fellow committee members over the next 17 days, but mostly wrote the Declaration of Independence in isolation between June 11 and 28, 1776, from the second floor of a three-story Georgian-style home he was renting at 700 Market Street in Center City Philadelphia; the residence was then owned by Jacob Graff, a bricklayer whose grandparents had emigrated to Philadelphia from Germany in 1741.[67] In authoring the Declaration, Jefferson drew considerably on his proposed draft of the Virginia Constitution, George Mason's draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, and other sources.[68] Other committee members made some changes, and a final draft was presented to Congress on June 28, 1776.[69]

The declaration was introduced on Friday, June 28, and Congress began debate over its contents on Monday, July 1,[69] resulting in the removal of roughly a fourth of Jefferson's original draft,[70] including a passage authored that was critical of King George III and "Jefferson's anti-slavery clause", which criticized King George III for importing slavery to the colonies.[71][72] Jefferson resented the changes, but he did not speak publicly about the revisions.[lower-alpha 7]

On July 4, 1776, the Congress ratified the Declaration, and delegates signed it on August 2; in so doing, the delegates were knowingly committing an act of high treason against The Crown, which was deemed the most serious criminal offense and was punishable by torture and death, including hanging almost to the point of death followed by emasculation, disembowelment, decapitation, and dismemberment (chopped into four pieces) with the remains then often displayed in public to serve as a warning of the fate of traitors.[74]

Jefferson's preamble is regarded as an enduring statement on individual and human rights, and the phrase "all men are created equal" has been called "one of the best-known sentences in the English language". The Declaration of Independence, historian Joseph Ellis wrote in 2008, represents "the most potent and consequential words in American history".[71][75]

Virginia state legislator and governor

At the start of the Revolution, Colonel Jefferson was named commander of the Albemarle County Militia on September 26, 1775.[76] He was then elected to the Virginia House of Delegates for Albemarle County in September 1776, when finalizing the state constitution was a priority.[77][78] For nearly three years, he assisted with the constitution and was especially proud of his Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, which prohibited state support of religious institutions or enforcement of religious doctrine.[79] The bill failed to pass, as did his legislation to disestablish the Anglican Church, but both were later revived by James Madison.[80]

In 1778, Jefferson was given the task of revising the state's laws. He drafted 126 bills in three years, including laws to streamline the judicial system. He proposed statutes that provided for general education, which he considered the basis of "republican government".[77] Jefferson also was concerned that Virginia's powerful landed gentry were becoming a hereditary aristocracy and he took the lead in abolishing what he called "feudal and unnatural distinctions."[81] He targeted laws such as entail and primogeniture by which a deceased landowner's oldest son was vested with all land ownership and power.[81] [lower-alpha 8]

Jefferson was elected governor for one-year terms in 1779 and 1780.[83] He transferred the state capital from Williamsburg to Richmond, and introduced additional measures for public education, religious freedom, and inheritance.[84]

During General Benedict Arnold's 1781 invasion of Virginia, Jefferson escaped Richmond just ahead of the British forces, which razed the city.[85][86] He sent emergency dispatches to Colonel Sampson Mathews and other commanders in an attempt to repel Arnold's efforts.[87][88] Jefferson then visited with friends in the surrounding counties of Richmond, including William Fleming, a college friend of his in Chesterfield County.[89] General Charles Cornwallis that spring dispatched a cavalry force led by Banastre Tarleton to capture Jefferson and members of the Assembly at Monticello, but Jack Jouett of the Virginia militia thwarted the British plan. Jefferson escaped to Poplar Forest, his plantation to the west.[90] When the General Assembly reconvened in June 1781, it conducted an inquiry into Jefferson's actions which eventually concluded that Jefferson had acted with honor—but he was not re-elected.[91]

In April of the same year, his daughter Lucy died at age one. A second daughter of that name was born the following year, but she died at age three.[92]

In 1782, Jefferson refused a partnership offer by North Carolina Governor Abner Nash, in a profiteering scheme involving the sale of confiscated Loyalist lands.[93] Unlike some Founders in pursuit of land, Jefferson was content with his Monticello estate and the land he owned in the vicinity of Virginia's Shenandoah Valley. Jefferson thought of Monticello as an intellectual gathering place for his friends James Madison and James Monroe.[94]

Notes on the State of Virginia

In 1780, Jefferson received from French diplomat François Barbé-Marbois a letter of inquiry into the geography, history, and government of Virginia, as part of a study of the United States. Jefferson organized his responses in a book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785).[95] He compiled the book over five years, including reviews of scientific knowledge, Virginia's history, politics, laws, culture, and geography.[96] The book explores what constitutes a good society, using Virginia as an exemplar. Jefferson included extensive data about the state's natural resources and economy and wrote at length about slavery and miscegenation; he articulated his belief that blacks and whites could not live together as free people in one society because of justified resentments of the enslaved.[97] He also wrote of his views on the American Indian, equating them to European settlers in body and mind.[98][99]

Notes was first published in 1785 in French and appeared in English in 1787.[100] Biographer George Tucker considered the work "surprising in the extent of the information which a single individual had been thus far able to acquire, as to the physical features of the state";[101] Merrill D. Peterson described it as an accomplishment for which all Americans should be grateful.[102]

Member of Congress

Jefferson was appointed a Virginia delegate to the Congress of the Confederation organized following victory in the Revolutionary War and the peace treaty with Great Britain in 1783. He was a member of the committee setting foreign exchange rates and recommended an American currency based on the decimal system which was adopted.[103] He advised the formation of the Committee of the States to fill the power vacuum when Congress was in recess.[104] The Committee met when Congress adjourned, but disagreements rendered it dysfunctional.[105]

In the Congress' 1783–1784 session, Jefferson acted as chairman of committees to establish a viable system of government for the new Republic and to propose a policy for the settlement of the western territories. He was the principal author of the Land Ordinance of 1784, whereby Virginia ceded to the national government the vast area that it claimed northwest of the Ohio River. He insisted that this territory should not be used as colonial territory by any of the thirteen states, but that it should be divided into sections that could become states. He plotted borders for nine new states in their initial stages and wrote an ordinance banning slavery in all the nation's territories. Congress made extensive revisions, and rejected the ban on slavery.[106][107] The provisions banning slavery, known as the "Jefferson Proviso", were modified and implemented three years later in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and became the law for the entire Northwest Territory.[106]

Minister to France

On May 7, 1784, Jefferson was appointed by the Congress of the Confederation[lower-alpha 9] to join Benjamin Franklin and John Adams in Paris as Minister Plenipotentiary for Negotiating Treaties of Amity and Commerce with Great Britain and other countries.[108][lower-alpha 10] With his young daughter Patsy and two servants, he departed in July 1784, arriving in Paris the next month.[110][111] Jefferson had Patsy educated at the Pentemont Abbey. Less than a year later he was assigned the additional duty of succeeding Franklin as Minister to France. French foreign minister Count de Vergennes commented, "You replace Monsieur Franklin, I hear." Jefferson replied, "I succeed. No man can replace him."[112] During his five years in Paris, Jefferson played a leading role in shaping U.S. foreign policy.[113]

In 1786, he met and fell in love with Maria Cosway, an accomplished—and married—Italian-English musician of 27. They saw each other frequently over a period of six weeks. She returned to Great Britain, but they maintained a lifelong correspondence.[114]

During the summer of 1786, Jefferson arrived in London to meet with John Adams, the United States Ambassador to Britain. Adams had official access to George III and arranged a meeting between Jefferson and the king. Jefferson later described the king's reception of the men as "ungracious." According to Adams's grandson, George III turned his back on both Adams and Jefferson in a jesture of public insult. Jefferson returned to France in August.[115]

Jefferson sent for his youngest surviving child, nine-year-old Polly, in June 1787. She was accompanied on her voyage by a young slave from Monticello, Sally Hemings. Jefferson had taken her older brother, James Hemings, to Paris as part of his domestic staff and had him trained in French cuisine.[116] According to Sally's son, Madison Hemings, the 16-year-old Sally and Jefferson began a sexual relationship in Paris, where she became pregnant.[117] The son also indicated Hemings agreed to return to the United States only after Jefferson promised to free her children when they came of age.[117]

While in France, Jefferson became a regular companion of the Marquis de Lafayette, a French hero of the American Revolutionary War, and Jefferson used his influence to procure trade agreements with France.[118][119] As the French Revolution began, he allowed his Paris residence, the Hôtel de Langeac, to be used for meetings by Lafayette and other republicans. He was in Paris during the storming of the Bastille and consulted with Lafayette while the latter drafted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[120] Jefferson often found his mail opened by postmasters, so he invented his own enciphering device, the "Wheel Cipher"; he wrote important communications in code for the rest of his career.[121][lower-alpha 11] Unable to attend the 1787 Constitution Convention, Jefferson supported the Constitution but desired the addition of the promised bill of rights.[122] Jefferson left Paris for America in September 1789, intending to return to his home soon; however, President George Washington appointed him the country's first secretary of state, forcing him to remain in the nation's capital.[123] Jefferson remained a firm supporter of the French Revolution while opposing its more violent elements.[124] John Skey Eustace kept Jefferson informed of the events of the French Revolution.[125]

Secretary of State

Soon after returning from France, Jefferson accepted President Washington's invitation to serve as Secretary of State.[126] Pressing issues at this time were the national debt and the permanent location of the capital. He opposed a national debt, preferring that each state retire its own, in contrast to Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, who desired consolidation of various states' debts by the federal government.[127] Hamilton also had bold plans to establish the national credit and a national bank, but Jefferson strenuously opposed this and attempted to undermine his agenda, which nearly led Washington to dismiss him from his cabinet. He later left the cabinet voluntarily.[128]

The second major issue was the capital's permanent location. Hamilton favored a capital close to the major commercial centers of the Northeast, while Washington, Jefferson, and other agrarians wanted it located further south.[129] After lengthy deadlock, the Compromise of 1790 was struck, permanently locating the capital on the Potomac River, and the federal government assumed the war debts of all original 13 states.[129]

Jefferson's goals were to decrease American dependence on British commerce and to expand commercial trade with France. He sought to weaken Spanish colonialism of the trans-Appalachian West and British control in the North, believing this would aid in the pacification of Native Americans.[130]

While serving in the government in Philadelphia, Jefferson and political protegé Congressman James Madison founded the National Gazette in 1791, along with author Phillip Freneau, in an effort to counter Hamilton's Federalist policies, which Hamilton was promoting through the influential Federalist newspaper the Gazette of the United States. The National Gazette made particular criticism of the policies promoted by Hamilton, often through anonymous essays signed by the pen name Brutus at Jefferson's urging, which were actually written by Madison.[131] In Spring 1791, Jefferson and Madison took a vacation to Vermont at a moment when Jefferson had been suffering from migraines and was tiring of the in-fighting with Hamilton.[132]

In May 1792, Jefferson became alarmed at the political rivalries taking shape; he wrote to Washington, imploring him to run for reelection that year as a unifying influence.[133] He urged the president to rally the citizenry to a party that would defend democracy against the corrupting influence of banks and monied interests, as espoused by the Federalists. Historians recognize this letter as the earliest delineation of Democratic-Republican Party principles.[134] Jefferson, Madison, and other Democratic-Republican organizers favored states' rights and local control and opposed federal concentration of power, whereas Hamilton sought more power for the federal government.[135]

Jefferson supported France against Britain when the two nations fought in 1793, though his arguments in the Cabinet were undercut by French Revolutionary envoy Edmond-Charles Genêt's open scorn for President Washington.[136] In his discussions with British Minister George Hammond, he tried in vain to persuade the British to vacate their posts in the Northwest and to compensate the U.S. for slaves whom the British had freed at the end of the war. Jefferson sought a return to private life, and resigned the cabinet position in December 1793; he may also have wanted to bolster his political influence from outside the administration.[137]

After the Washington administration negotiated the Jay Treaty with Great Britain in 1794, Jefferson saw a cause around which to rally his party and organized a national opposition from Monticello.[138] The treaty, designed by Hamilton, aimed to reduce tensions and increase trade. Jefferson warned that it would increase British influence and subvert republicanism, calling it "the boldest act [Hamilton and Jay] ever ventured on to undermine the government".[139] The Treaty passed, but it expired in 1805 during Jefferson's presidential administration and was not renewed. Jefferson continued his pro-France stance; during the violence of the Reign of Terror, he declined to disavow the revolution: "To back away from France would be to undermine the cause of republicanism in America."[140]

Election of 1796 and vice presidency

In the presidential campaign of 1796, Jefferson lost the electoral college vote to Federalist John Adams by 71–68 and was thus elected vice president. As presiding officer of the Senate, he assumed a more passive role than his predecessor John Adams. He allowed the Senate to freely conduct debates and confined his participation to procedural issues, which he called an "honorable and easy" role.[141] Jefferson had previously studied parliamentary law and procedure for 40 years, making him quite qualified to serve as presiding officer. In 1800, he published his assembled notes on Senate procedure as A Manual of Parliamentary Practice.[142] He cast only three tie-breaking votes in the Senate.

In four confidential talks with French consul Joseph Létombe in the spring of 1797, Jefferson attacked Adams and predicted that his rival would serve only one term. He also encouraged France to invade England, and advised Létombe to stall any American envoys sent to Paris by instructing him to "listen to them and then drag out the negotiations at length and mollify them by the urbanity of the proceedings."[143] This toughened the tone that the French government adopted toward the Adams administration. After Adams's initial peace envoys were rebuffed, Jefferson and his supporters lobbied for the release of papers related to the incident, called the XYZ Affair after the letters used to disguise the identities of the French officials involved.[144] However, the tactic backfired when it was revealed that French officials had demanded bribes, rallying public support against France. The U.S. began an undeclared naval war with France known as the Quasi-War.[145]

During the Adams presidency, the Federalists rebuilt the military, levied new taxes, and enacted the Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson believed these laws were intended to suppress Democratic-Republicans, rather than prosecute enemy aliens, and considered them unconstitutional.[146] To rally opposition, he and James Madison anonymously wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, declaring that the federal government had no right to exercise powers not specifically delegated to it by the states.[147] The resolutions followed the "interposition" approach of Madison, in which states may shield their citizens from federal laws that they deem unconstitutional. Jefferson advocated nullification, allowing states to invalidate federal laws altogether.[148][lower-alpha 12] He warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold", the Alien and Sedition Acts would "necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood".[150]

Historian Ron Chernow claims that "the theoretical damage of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions was deep and lasting, and was a recipe for disunion", contributing to the American Civil War as well as later events.[151] Washington was so appalled by the resolutions that he told Patrick Henry that, if "systematically and pertinaciously pursued", the resolutions would "dissolve the union or produce coercion."[152] Jefferson had always admired Washington's leadership skills but felt that his Federalist party was leading the country in the wrong direction. He decided not to attend Washington's funeral in 1799 because of acute differences with him while serving as secretary of state.[153]

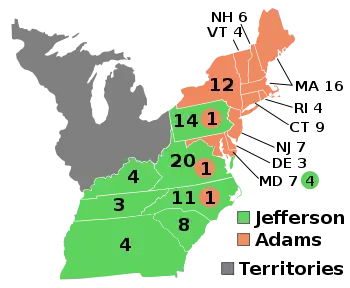

Election of 1800

Jefferson contended for president once more against John Adams in 1800. Adams' campaign was weakened by unpopular taxes and vicious Federalist infighting over his actions in the Quasi-War.[154] Democratic-Republicans pointed to the Alien and Sedition Acts and accused the Federalists of being secret pro-Britain monarchists, while Federalists charged that Jefferson was a godless libertine beholden to the French.[155] Historian Joyce Appleby said the election was "one of the most acrimonious in the annals of American history".[156]

The Democratic-Republicans ultimately won more electoral college votes, due in part to the electors that resulted from the addition of three-fifths of the South's slaves to the population calculation under the Three-Fifths Compromise.[157] Jefferson and his vice-presidential candidate Aaron Burr unexpectedly received an equal total. Because of the tie, the election was decided by the Federalist-dominated House of Representatives.[158][lower-alpha 13] Hamilton lobbied Federalist representatives on Jefferson's behalf, believing him a lesser political evil than Burr. On February 17, 1801, after thirty-six ballots, the House elected Jefferson president and Burr vice president. Jefferson became the second incumbent vice president to be elected president.[159]

The win was marked by Democratic-Republican celebrations throughout the country.[160] Some of Jefferson's opponents argued that he owed his victory over Adams to the South's inflated number of electors.[161] Others alleged that Jefferson secured James Asheton Bayard's tie-breaking electoral vote by guaranteeing the retention of various Federalist posts in the government.[159] Jefferson disputed the allegation, and the historical record is inconclusive.[162]

The transition proceeded smoothly, marking a watershed in American history. As historian Gordon S. Wood writes, "it was one of the first popular elections in modern history that resulted in the peaceful transfer of power from one 'party' to another."[159]

Presidency (1801–1809)

Jefferson was sworn in as president by Chief Justice John Marshall at the new Capitol in Washington, D.C., on March 4, 1801. His inauguration was not attended by outgoing President Adams. In contrast to his two predecessors, Jefferson exhibited a dislike of formal etiquette. Plainly dressed, he chose to walk alongside friends to the Capitol from his nearby boardinghouse that day instead of arriving by carriage.[163] His inaugural address struck a note of reconciliation and commitment to democratic ideology, declaring, "We have been called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists."[164][165] Ideologically, he stressed "equal and exact justice to all men", minority rights, and freedom of speech, religion, and press.[166] He said that a free and democratic government was "the strongest government on earth."[166] He nominated moderate Republicans to his cabinet: James Madison as secretary of state, Henry Dearborn as secretary of war, Levi Lincoln as attorney general, and Robert Smith as secretary of the navy.[165]

Widowed since 1782, Jefferson first relied on his two daughters to serve as his official hostesses.[167] In late May 1801, he asked Dolley Madison, wife of his long-time friend James Madison, to be the permanent White House hostess. She accepted, realizing the diplomatic importance of the position. She was also in charge of the completion of the White House mansion. Dolley served as White House hostess for the rest of Jefferson's two terms and then for eight more years as First Lady while her husband served as president.[167]

Financial affairs

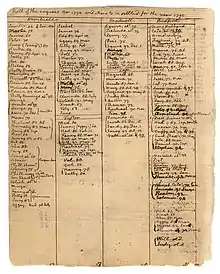

.jpg.webp)

Jefferson's first challenge as president was shrinking the $83 million national debt.[168] He began dismantling Hamilton's Federalist fiscal system with help from the Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.[165] Gallatin devised a plan to eliminate the national debt in sixteen years by extensive annual appropriations and reduction in taxes.[169] The administration eliminated the whiskey excise and other taxes after closing "unnecessary offices" and cutting "useless establishments and expenses".[170][171]

Jefferson believed that the First Bank of the United States represented a "most deadly hostility" to republican government.[169] He wanted to dismantle the bank before its charter expired in 1811, but was dissuaded by Gallatin.[172] Gallatin argued that the national bank was a useful financial institution and set out to expand its operations.[173] Jefferson looked to other corners to address the growing national debt.[173] He shrank the Navy, for example, deeming it unnecessary in peacetime, and incorporated a fleet of inexpensive gunboats intended only for local defense to avoid provocation against foreign powers.[170] After two terms, he had lowered the national debt from $83 million to $57 million.[174]

Domestic affairs

Jefferson pardoned several of those imprisoned under the Alien and Sedition Acts.[175] Congressional Republicans repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801, which removed nearly all of Adams's "midnight judges" from office. A subsequent appointment battle led to the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Marbury v. Madison, asserting judicial review over executive branch actions.[176] Jefferson appointed three Supreme Court justices: William Johnson (1804), Henry Brockholst Livingston (1807), and Thomas Todd (1807).[177]

Jefferson strongly felt the need for a national military university, producing an officer engineering corps for a national defense based on the advancement of the sciences, rather than having to rely on foreign sources for top grade engineers with questionable loyalty.[178] He signed the Military Peace Establishment Act on March 16, 1802, thus founding the United States Military Academy at West Point. The Act documented in 29 sections a new set of laws and limits for the military. Jefferson was also hoping to bring reform to the Executive branch, replacing Federalists and active opponents throughout the officer corps to promote Republican values.[179]

Jefferson took great interest in the Library of Congress, which had been established in 1800. He often recommended books to acquire. In 1802, Congress authorized President Jefferson to name the first Librarian of Congress, and formed a committee to establish library rules and regulations. Congress also granted the president and vice president the right to use the library.[180]

First Barbary War

American merchant ships had been protected from Barbary Coast pirates by the Royal Navy when the states were British colonies.[181] After independence, however, pirates often captured U.S. merchant ships, pillaged cargoes, and enslaved or held crew members for ransom. Jefferson had opposed paying tribute to the Barbary States since 1785. In 1801, he authorized a U.S. Navy fleet under Commodore Richard Dale to make a show of force in the Mediterranean, the first American naval squadron to cross the Atlantic.[182] Following the fleet's first engagement, he successfully asked Congress for a declaration of war.[182] The subsequent "First Barbary War" was the first foreign war fought by the U.S.[183]

Pasha of Tripoli Yusuf Karamanli captured the USS Philadelphia, so Jefferson authorized William Eaton, the U.S. Consul to Tunis, to lead a force to restore the pasha's older brother to the throne.[184] The American navy forced Tunis and Algiers into breaking their alliance with Tripoli. Jefferson ordered five separate naval bombardments of Tripoli, leading the pasha to sign a treaty that restored peace in the Mediterranean.[185] This victory proved only temporary, but according to Wood, "many Americans celebrated it as a vindication of their policy of spreading free trade around the world and as a great victory for liberty over tyranny."[186]

Louisiana Purchase

Spain ceded ownership of the Louisiana territory in 1800 to the more predominant France. Jefferson was greatly concerned that Napoleon's broad interests in the vast territory would threaten the security of the continent and Mississippi River shipping. He wrote that the cession "works most sorely on the U.S. It completely reverses all the political relations of the U.S."[187] In 1802, he instructed James Monroe and Robert R. Livingston to negotiate with Napoleon to purchase New Orleans and adjacent coastal areas from France.[188] In early 1803, Jefferson offered Napoleon nearly $10 million for 40,000 square miles (100,000 square kilometers) of tropical territory.[189]

Napoleon realized that French military control was impractical over such a vast remote territory, and he was in dire need of funds for his wars on the home front. In early April 1803, he unexpectedly made negotiators a counter-offer to sell 827,987 square miles (2,144,480 square kilometers) of French territory for $15 million (~$337 million in 2021), doubling the size of the United States.[189] U.S. negotiators seized this unique opportunity and accepted the offer and signed the treaty on April 30, 1803.[174] Word of the unexpected purchase did not reach Jefferson until July 3, 1803.[174] He unknowingly acquired the most fertile tract of land of its size on Earth, making the new country self-sufficient in food and other resources. The sale also significantly curtailed the European presence in North America, removing obstacles to U.S. westward expansion.[190]

Most thought that this was an exceptional opportunity, despite Republican reservations about the Constitutional authority of the federal government to acquire land.[191] Jefferson initially thought that a Constitutional amendment was necessary to purchase and govern the new territory; but he later changed his mind, fearing that this would give cause to oppose the purchase, and he therefore urged a speedy debate and ratification.[192] On October 20, 1803, the Senate ratified the purchase treaty by a vote of 24–7.[193] Jefferson personally was humble about acquiring the Louisiana Territory, but he resented complainers who called the vast domain a "howling wilderness".[194]

After the purchase, Jefferson preserved the region's Spanish legal code and instituted a gradual approach to integrating settlers into American democracy. He believed that a period of the federal rule would be necessary while Louisianans adjusted to their new nation.[195][lower-alpha 14] Historians have differed in their assessments regarding the constitutional implications of the sale,[197] but they typically hail the Louisiana acquisition as a major accomplishment. Frederick Jackson Turner called the purchase the most formative event in American history.[190]

Lewis and Clark Expedition (1803–1806)

Jefferson anticipated further westward settlements due to the Louisiana Purchase and arranged for the exploration and mapping of the uncharted territory. He sought to establish a U.S. claim ahead of competing European interests and to find the rumored Northwest Passage.[198] Jefferson and others were influenced by exploration accounts of Le Page du Pratz in Louisiana (1763) and Captain James Cook in the Pacific (1784),[199] and they persuaded Congress in 1804 to fund an expedition to explore and map the newly acquired territory to the Pacific Ocean.[200]

Jefferson appointed Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to be leaders of the Corps of Discovery (1803–1806).[201] In the months leading up to the expedition, Jefferson tutored Lewis in the sciences of mapping, botany, natural history, mineralogy, and astronomy and navigation, giving him unlimited access to his library at Monticello, which included the largest collection of books in the world on the subject of the geography and natural history of the North American continent, along with an impressive collection of maps.[202]

The expedition lasted from May 1804 to September 1806 (see timeline) and obtained a wealth of scientific and geographic knowledge, including knowledge of many Indian tribes.[203]

- Other expeditions

In addition to the Corps of Discovery, Jefferson organized three other western expeditions: the William Dunbar and George Hunter Expedition on the Ouachita River (1804–1805), the Thomas Freeman and Peter Custis Expedition (1806) on the Red River, and the Zebulon Pike Expedition (1806–1807) into the Rocky Mountains and the Southwest. All three produced valuable information about the American frontier.[204]

Native American affairs

Jefferson's experiences with the American Indians began during his boyhood in Virginia and extended through his political career and into his retirement. He refuted the contemporary notion that Indians were inferior people and maintained that they were equal in body and mind to people of European descent.[205]

As governor of Virginia during the Revolutionary War, Jefferson recommended moving the Cherokee and Shawnee tribes, who had allied with the British, to west of the Mississippi River. But when he took office as president, he quickly took measures to avert another major conflict, as American and Indian societies were in collision and the British were inciting Indian tribes from Canada.[206][207] In Georgia, he stipulated that the state would release its legal claims for lands to its west in exchange for military support in expelling the Cherokee from Georgia. This facilitated his policy of western expansion, to "advance compactly as we multiply".[208]

In keeping with his Enlightenment thinking, President Jefferson adopted an assimilation policy toward American Indians known as his "civilization program" which included securing peaceful U.S. – Indian treaty alliances and encouraging agriculture. Jefferson advocated that Indian tribes should make federal purchases by credit holding their lands as collateral for repayment. Various tribes accepted Jefferson's policies, including the Shawnees led by Black Hoof, the Muscogee, and the Cherokee. However, some Shawnees, led by Tecumseh, broke off from Black Hoof, and opposed Jefferson's assimilation policies.[209]

Historian Bernard Sheehan argues that Jefferson believed that assimilation was best for American Indians; second best was removal to the west. He felt that the worst outcome of the cultural and resources conflict between American citizens and American Indians would be their attacking the whites.[207] Jefferson told U.S. Secretary of War Henry Dearborn, who then oversaw Indian affairs under the War Department, "If we are constrained to lift the hatchet against any tribe, we will never lay it down until that tribe is exterminated or driven beyond the Mississippi."[210] Miller agrees that Jefferson believed that Indians should assimilate to American customs and agriculture. Historians such as Peter S. Onuf and Merrill D. Peterson argue that Jefferson's actual Indian policies did little to promote assimilation and were a pretext to seize lands.[211]

Re-election in 1804 and second term

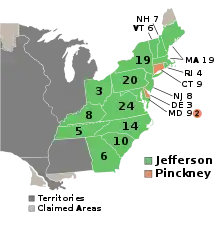

Jefferson's successful first term resulted in him being nominated for reelection by the Republican party, and George Clinton replacing Burr as his running mate.[212] The Federalist party ran Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina, John Adams's vice-presidential candidate in the 1800 election. The Jefferson-Clinton ticket won overwhelmingly in the electoral college vote, by 162 to 14, promoting their achievement of a strong economy, lower taxes, and the Louisiana Purchase.[212]

In March 1806, a split developed in the Republican party, led by fellow Virginian and former Republican ally John Randolph, who viciously accused President Jefferson on the floor of the House of moving too far in the Federalist direction. In so doing, Randolph permanently set himself apart politically from Jefferson. Jefferson and Madison had backed resolutions to limit or ban British imports in retaliation for British seizures of American shipping. Also, in 1808, Jefferson was the first president to propose a broad Federal plan to build roads and canals across several states, asking for $20 million, further alarming Randolph and believers of limited government.[213]

Jefferson's popularity further suffered in his second term due to his response to wars in Europe. Positive relations with Great Britain had diminished, due partly to the antipathy between Jefferson and British diplomat Anthony Merry. After Napoleon's decisive victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, Napoleon became more aggressive in his negotiations over trading rights, which American efforts failed to counter. Jefferson then led the enactment of the Embargo Act of 1807, directed at both France and Great Britain. This triggered economic chaos in the U.S. and was strongly criticized at the time, resulting in Jefferson having to abandon the policy a year later.[214]

During the revolutionary era, the states abolished the international slave trade, but South Carolina reopened it. In his annual message of December 1806, Jefferson denounced the "violations of human rights" attending the international slave trade, calling on the newly elected Congress to criminalize it immediately. In 1807, Congress passed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, which Jefferson signed.[215][216] The act established severe punishment against the international slave trade, although it did not address the issue domestically.[217]

In Haiti, Jefferson's neutrality had allowed arms to enable the slave independence movement during its Revolution, and blocked attempts to assist Napoleon, who was defeated there in 1803.[218] But he refused official recognition of the country during his second term, in deference to southern complaints about the racial violence against slave-holders; it was eventually extended to Haiti in 1862.[219]

Burr conspiracy and trial

Following the 1801 electoral deadlock, Jefferson's relationship with his vice president, former New York Senator Aaron Burr, rapidly eroded. Jefferson suspected Burr of seeking the presidency for himself, while Burr was angered by Jefferson's refusal to appoint some of his supporters to federal office. Burr was dropped from the Democratic-Republican ticket in 1804.

The same year, Burr was soundly defeated in his bid to be elected New York governor. During the campaign, Alexander Hamilton publicly made callous remarks regarding Burr's moral character.[220] Subsequently, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel, mortally wounding him on July 11, 1804. Burr was indicted for Hamilton's murder in New York and New Jersey, causing him to flee to Georgia, although he remained President of the Senate during Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase's impeachment trial.[221] Both indictments quietly died and Burr was not prosecuted.[222] Also during the election, certain New England separatists approached Burr, desiring a New England federation and intimating that he would be their leader.[223] However, nothing came of the plot, since Burr had lost the election and his reputation was ruined after killing Hamilton.[223] In August 1804, Burr contacted British Minister Anthony Merry offering to cede U.S. western territory in return for money and British ships.[224]

After leaving office in April 1805, Burr traveled west and conspired with Louisiana Territory governor James Wilkinson, beginning a large-scale recruitment for a military expedition.[225] Other plotters included Ohio Senator John Smith and an Irishman named Harmon Blennerhassett.[225] Burr discussed a number of plots—seizing control of Mexico or Spanish Florida, or forming a secessionist state in New Orleans or the Western U.S. Historians remain unclear as to his true goal.[226][lower-alpha 15]

In the fall of 1806, Burr launched a military flotilla carrying about 60 men down the Ohio River. Wilkinson renounced the plot, apparently from self-interested motives; he reported Burr's expedition to Jefferson, who immediately ordered Burr's arrest.[225][228][229] On February 13, 1807, Burr was captured in Louisiana's Bayou Pierre wilderness and sent to Virginia to be tried for treason.[224]

Burr's 1807 conspiracy trial became a national issue.[230] Jefferson attempted to preemptively influence the verdict by telling Congress that Burr's guilt was "beyond question", but the case came before his longtime political foe John Marshall, who dismissed the treason charge. Burr's legal team at one stage subpoenaed Jefferson, but Jefferson refused to testify, making the first argument for executive privilege. Instead, Jefferson provided relevant legal documents.[231] After a three-month trial, the jury found Burr not guilty, while Jefferson denounced his acquittal.[229][232][lower-alpha 16][233] Jefferson subsequently removed Wilkinson as territorial governor but retained him in the U.S. military. Historian James N. Banner criticized Jefferson for continuing to trust Wilkinson, a "faithless plotter".[229]

General Wilkinson misconduct

Commanding General James Wilkinson was a holdover of the Washington and Adams administrations. Wilkinson was rumored to be a "skillful and unscrupolous plotter". In 1804, Wilkinson received 12,000 pesos from the Spanish for information on American boundary plans.[234] Wilkinson also received advances on his salary and payments on claims submitted to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn. This damaging information apparently was unknown to Jefferson. In 1805, Jefferson trusted Wilkinson and appointed him Louisiana Territory governor, admiring Wilkinson's work ethic.

In January 1806, Jefferson received information from Kentucky U.S. Attorney Joseph Davies that Wilkinson was on the Spanish payroll. Jefferson took no action against Wilkinson, since there was not then significant evidence against him.[235] An investigation by the U.S. House of Representatives in December 1807 exonerated Wilkinson.[236] In 1808, a military court looked into the allegations against Wilkinson but also found a lack of evidence to charge him. Jefferson retained Wilkinson in the U.S. Army, and Jefferson passed him on to James Madison, his successor as president.[237] Evidence found in Spanish archives in the 20th century proved Wilkinson was, in fact, on the Spanish payroll.[234]

Attempted annexation of Florida

In the aftermath of the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson attempted to annex West Florida from Spain, a nation under the control of Emperor Napoleon and the French Empire after 1804. In his annual message to Congress, on December 3, 1805, Jefferson railed against Spain over Florida border depredations.[238][239] A few days later Jefferson secretly requested a two million dollar expenditure to purchase Florida. Representative and floor leader John Randolph, however, opposed annexation and was upset over Jefferson's secrecy on the matter, and believed the money would land in the coffers of Napoleon.[240][239] The Two Million Dollar bill passed only after Jefferson successfully maneuvered to replace Randolph with Barnabas Bidwell as floor leader.[240][239] This aroused suspicion of Jefferson and charges of undue executive influence over Congress. Jefferson signed the bill into law in February 1806. Six weeks later the law was made public. The two million dollars was to be given to France as payment, in turn, to put pressure on Spain to permit the annexation of Florida by the United States. France, however, was in no mood to allow Spain to give up Florida and refused the offer. Florida remained under the control of Spain.[241][239] The failed venture damaged Jefferson's reputation among his supporters.[242][239]

Chesapeake–Leopard affair

The British conducted seizures of American shipping to search for British deserters from 1806 to 1807; American citizens were thus impressed into the British naval service. In 1806, Jefferson issued a call for a boycott of British goods; on April 18, Congress passed the Non-Importation Acts, but they were never enforced. Later that year, Jefferson asked James Monroe and William Pinkney to negotiate with Great Britain to end the harassment of American shipping, though Britain showed no signs of improving relations. The Monroe–Pinkney Treaty was finalized but lacked any provisions to end the British policies, and Jefferson refused to submit it to the Senate for ratification.[243]

The British ship HMS Leopard fired upon the USS Chesapeake off the Virginia coast in June 1807, and Jefferson prepared for war.[244] He issued a proclamation banning armed British ships from U.S. waters. He presumed unilateral authority to call on the states to prepare 100,000 militia and ordered the purchase of arms, ammunition, and supplies, writing, "The laws of necessity, of self-preservation, of saving our country when in danger, are of higher obligation [than strict observance of written laws]". The USS Revenge was dispatched to demand an explanation from the British government; it also was fired upon. Jefferson called for a special session of Congress in October to enact an embargo or alternatively to consider war.[245]

Embargo (1807–1809)

In December 1807, news arrived that Napoleon had extended the Berlin Decree, globally banning British imports. In Britain, King George III ordered redoubling efforts at impressment, including American sailors. But the war fever of the summer faded; Congress had no appetite to prepare the U.S. for war. Jefferson asked for and received the Embargo Act, an alternative that allowed the U.S. more time to build up defensive works, militias, and naval forces. Later historians have seen the irony in Jefferson's assertion of such federal power. Meacham said that the Embargo Act was a projection of power that surpassed the Alien and Sedition Acts, and R. B. Bernstein said that Jefferson "was pursuing policies resembling those he had cited in 1776 as grounds for independence and revolution".[246]

In November 1807, Jefferson, for several days, met with his cabinet to discuss the deteriorating foreign situation.[247] Secretary of State James Madison supported the embargo with equal vigor to Jefferson,[248] while Treasury Secretary Gallatin opposed it, due to its indefinite time frame and the risk that it posed to the policy of American neutrality.[249] The U.S. economy suffered, criticism grew, and opponents began evading the embargo. Instead of retreating, Jefferson sent federal agents to secretly track down smugglers and violators.[250] Three acts were passed in Congress during 1807 and 1808, called the Supplementary, the Additional, and the Enforcement acts.[244] The government could not prevent American vessels from trading with the European belligerents once they had left American ports, although the embargo triggered a devastating decline in exports.[244]

In December 1807, Jefferson announced his intention not to seek a third term. He turned his attention increasingly to Monticello during the last year of his presidency, giving Madison and Gallatin almost total control of affairs.[251] Shortly before leaving office in March 1809, Jefferson signed the repeal of the Embargo. In its place, the Non-Intercourse Act was passed, but it proved no more effective.[244] The day before Madison was inaugurated as his successor, Jefferson said that he felt like "a prisoner, released from his chains".[252]

Cabinet

| The Jefferson cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Thomas Jefferson | 1801–1809 |

| Vice President | Aaron Burr | 1801–1805 |

| George Clinton | 1805–1809 | |

| Secretary of State | James Madison | 1801–1809 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Samuel Dexter | 1801 |

| Albert Gallatin | 1801–1809 | |

| Secretary of War | Henry Dearborn | 1801–1809 |

| Attorney General | Levi Lincoln Sr. | 1801–1805 |

| John Breckinridge | 1805–1806 | |

| Caesar Augustus Rodney | 1807–1809 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Benjamin Stoddert | 1801 |

| Robert Smith | 1801–1809 | |

Post-presidency (1809–1826)

After the end of his term in office, Jefferson remained influential and continued to correspond with many of the country's leaders (including his two protégées who succeeded him as president); the Monroe Doctrine bears a strong resemblance to solicited advice that Jefferson gave to Monroe in 1823.[253] [254]

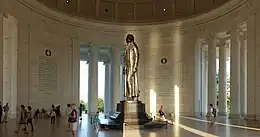

University of Virginia

Jefferson envisioned a university free of church influences where students could specialize in many new areas not offered at other colleges. He believed that education engendered a stable society, which should provide publicly funded schools accessible to students from all social strata, based solely on ability.[255] He initially proposed his University in a letter to Joseph Priestley in 1800[256] and, in 1819, the 76-year-old Jefferson founded the University of Virginia. He organized the state legislative campaign for its charter and, with the assistance of Edmund Bacon, purchased the location. He was the principal designer of the buildings, planned the university's curriculum, and served as the first rector upon its opening in 1825.[257]

Jefferson was a strong disciple of Greek and Roman architectural styles, which he believed to be most representative of American democracy. Each academic unit, called a pavilion, was designed with a two-story temple front, while the library "Rotunda" was modeled on the Roman Pantheon. Jefferson referred to the university's grounds as the "Academical Village", and he reflected his educational ideas in its layout. The ten pavilions included classrooms and faculty residences; they formed a quadrangle and were connected by colonnades, behind which stood the students' rows of rooms. Gardens and vegetable plots were placed behind the pavilions and were surrounded by serpentine walls, affirming the importance of the agrarian lifestyle.[258] The university had a library rather than a church at its center, emphasizing its secular nature—a controversial aspect at the time.[259]

When Jefferson died in 1826, James Madison replaced him as rector.[260] Jefferson bequeathed most of his reconstructed library of almost 2,000 volumes to the university.[261] Only one other ex-president has founded a university; Millard Fillmore, the nation's 13th president, founded the University at Buffalo two decades later, in 1846.[262]

Reconciliation with Adams

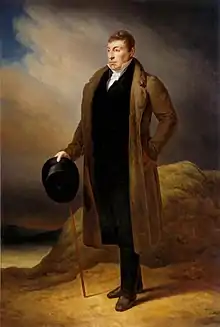

%252C_1800-1815%252C_NGA_42934.jpg.webp)

Jefferson and John Adams became good friends in the first decades of their political careers, serving together in the Continental Congress in the 1770s and in Europe in the 1780s. The Federalist/Republican split of the 1790s divided them, however, and Adams felt betrayed by Jefferson's sponsorship of partisan attacks, such as those of James Callender. Jefferson, on the other hand, was angered at Adams for his appointment of "midnight judges".[263] The two men did not communicate directly for more than a decade after Jefferson succeeded Adams as president.[264] A brief correspondence took place between Abigail Adams and Jefferson after Jefferson's daughter Polly died in 1804, in an attempt at reconciliation unknown to Adams. However, an exchange of letters resumed open hostilities between Adams and Jefferson.[263]

As early as 1809, Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Independence, desired that Jefferson and Adams reconcile and began to prod the two through correspondence to re-establish contact.[263] In 1812, Adams wrote a short New Year's greeting to Jefferson, prompted earlier by Rush, to which Jefferson warmly responded. This initial correspondence began what historian David McCullough calls "one of the most extraordinary correspondences in American history".[265] Over the next 14 years, Jefferson and Adams exchanged 158 letters discussing their political differences, justifying their respective roles in events, and debating the revolution's import to the world.[266]

When Adams died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, in Quincy, Massachusetts, his last words were an acknowledgment of his longtime friend and rival. "Thomas Jefferson survives", Adams said in his final words, unaware that Jefferson had died a few hours earlier the same day at Monticello.[267][268][269]

Autobiography

In 1821, at the age of 77, Jefferson began writing his autobiography, Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson: 1743–1790, in which he said he sought to "state some recollections of dates and facts concerning myself".[270] He focused on the struggles and achievements he experienced until July 29, 1790, where the narrative stopped short.[271] He excluded his youth, emphasizing the revolutionary era. He related that his ancestors came from Wales to America in the early 17th century and settled in the western frontier of the Virginia colony, which influenced his zeal for individual and state rights. Jefferson described his father as uneducated, but with a "strong mind and sound judgement". In the autobiography, he also addressed his enrollment in the College of William and Mary and his election to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1775.[270]

He also expressed opposition to the idea of a privileged aristocracy made up of large landowning families partial to the King, and instead promoted "the aristocracy of virtue and talent, which nature has wisely provided for the direction of the interests of society, & scattered with equal hand through all its conditions, was deemed essential to a well-ordered republic".[270]

Jefferson gave his insight into people, politics, and events.[270] The work is primarily concerned with the Declaration and reforming the government of Virginia. He used notes, letters, and documents to tell many of the stories within the autobiography. He suggested that this history was so rich that his personal affairs were better overlooked, but he incorporated a self-analysis using the Declaration and other patriotism.[272]

Greek War of Independence

Thomas Jefferson was a philhellene, lover of Greek culture, who sympathized with the Greek War of Independence.[273][274] He has been described as the most influential of the Founding Fathers who supported the Greek cause,[274][275] viewing it as similar to the American Revolution.[276] By 1823, Jefferson was exchanging ideas with Greek scholar Adamantios Korais.[274] Jefferson advised Korais on building the political system of Greece by using classical liberalism and examples from the American governmental system, ultimately prescribing a government akin to that of a U.S. state.[277] He also suggested the application of a classical education system for the newly founded First Hellenic Republic, where public education would be made available and pupils would be taught history, Latin, and Greek.[278] Jefferson's philosophical instructions were welcomed by the Greek people.[278] Korais became one of the designers of the Greek constitution and urged his associates to study Jefferson's works and other literature from the American Revolution.[278]

Lafayette's visit

In the summer of 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette accepted an invitation from President James Monroe to visit the country. Jefferson and Lafayette had not seen each other since 1789. After visits to New York, New England, and Washington, Lafayette arrived at Monticello on November 4.[257]

Jefferson's grandson Randolph was present and recorded the reunion: "As they approached each other, their uncertain gait quickened itself into a shuffling run, and exclaiming, 'Ah Jefferson!' 'Ah Lafayette!', they burst into tears as they fell into each other's arms." Jefferson and Lafayette then retired to the house to reminisce.[279] The next morning Jefferson, Lafayette, and James Madison attended a tour and banquet at the University of Virginia. Jefferson had someone else read a speech he had prepared for Lafayette, as his voice was weak and could not carry. This was his last public presentation. After an 11-day visit, Lafayette bid Jefferson goodbye and departed Monticello.[280]

Final days, death, and burial

Jefferson's approximately $100,000 of debt weighed heavily on his mind in his final months, as it became increasingly clear that he would have little to leave to his heirs. In February 1826, he successfully applied to the General Assembly to hold a public lottery as a fundraiser.[281] His health began to deteriorate in July 1825, due to a combination of rheumatism from arm and wrist injuries, as well as intestinal and urinary disorders.[257] By June 1826, he was confined to bed.[281] On July 3, overcome by fever, Jefferson declined an invitation to attend an anniversary celebration of the Declaration in the national capital of Washington.[282]

During the last hours of his life, he was accompanied by family members and friends. Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, at 12:50 p.m. at age 83, on the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, which he authored. In the moments prior to his death, Jefferson instructed his treating physician, "No, doctor, nothing more", refusing laudanum. But his final significant words were, "Is it the Fourth?" or "This is the Fourth".[283] When John Adams died later that same day, his last words included an acknowledgment of his longtime friend and rival, "Thomas Jefferson survives", though Adams was unaware that Jefferson had died several hours before.[284][285][286][287] The sitting president was Adams's son, John Quincy Adams, and he called the coincidence of their deaths on the nation's anniversary "visible and palpable remarks of Divine Favor".[288]

Shortly after Jefferson died, attendants found a gold locket on a chain around his neck, where it had rested for more than 40 years, containing a small faded blue ribbon that tied a lock of his wife Martha's brown hair.[289]

Jefferson was interred at Monticello, under an epitaph that he wrote:

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON, AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM, AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA.[290]

In his advanced years, Jefferson became increasingly concerned that people would understand the principles in the Declaration of Independence, and the people responsible for writing it, and he continually defended himself as its author. He considered the document one of his greatest life achievements, in addition to authoring the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom and his founding of the University of Virginia. Plainly absent from his epitaph were his political roles, including President of the United States.[291]

Jefferson died deeply in debt, and was unable to pass on his estate freely to his heirs.[292] He gave instructions in his will for disposal of his assets,[293] including the freeing of Sally Hemings's children;[294] but his estate, possessions, and slaves were sold at public auctions starting in 1827.[295] In 1831, Monticello was sold by Martha Jefferson Randolph and the other heirs.[296]

Political, social, and religious views

Jefferson subscribed to the political ideals expounded by John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton, whom he considered the three greatest men who ever lived.[297][298] He was also influenced by the writings of Gibbon, Hume, Robertson, Bolingbroke, Montesquieu, and Voltaire.[299] Jefferson thought that the independent yeoman and agrarian life were ideals of republican virtues. He distrusted cities and financiers, favored decentralized government power, and believed that the tyranny that had plagued the common man in Europe was due to corrupt political establishments and monarchies. He supported efforts to disestablish the Church of England,[300] wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and he pressed for a wall of separation between church and state.[301] The Republicans under Jefferson were strongly influenced by the 18th-century British Whig Party, which believed in limited government.[302] His Democratic-Republican Party became dominant in early American politics, and his views became known as Jeffersonian democracy.[303][304]

Philosophy, society, and government