Raymond Poincaré

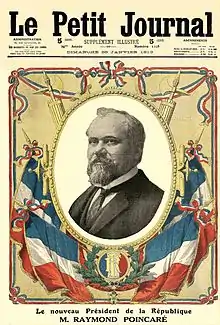

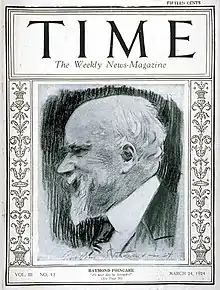

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (UK: /ˈpwæ̃kɑːreɪ/,[1] French: [ʁɛmɔ̃ pwɛ̃kaʁe]; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France.

Raymond Poincaré | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Official portrait, 1913 | |

| President of France | |

| In office 18 February 1913 – 18 February 1920 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Armand Fallières |

| Succeeded by | Paul Deschanel |

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 23 July 1926 – 29 July 1929 | |

| President | Gaston Doumergue |

| Preceded by | Édouard Herriot |

| Succeeded by | Aristide Briand |

| In office 15 January 1922 – 8 June 1924 | |

| President | Alexandre Millerand |

| Preceded by | Aristide Briand |

| Succeeded by | Frédéric François-Marsal |

| In office 21 January 1912 – 21 January 1913 | |

| President | Armand Fallières |

| Preceded by | Joseph Caillaux |

| Succeeded by | Aristide Briand |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 15 January 1922 – 8 June 1924 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Aristide Briand |

| Succeeded by | Edmond Lefebvre du Prey |

| In office 14 January 1912 – 21 January 1913 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Justin de Selves |

| Succeeded by | Charles Jonnart |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 23 July 1926 – 11 November 1928 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Anatole de Monzie |

| Succeeded by | Henry Chéron |

| In office 14 March 1906 – 25 October 1906 | |

| Prime Minister | Ferdinand Sarrien |

| Preceded by | Pierre Merlou |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Caillaux |

| In office 30 May 1894 – 26 January 1895 | |

| Prime Minister | Charles Dupuy |

| Preceded by | Auguste Burdeau |

| Succeeded by | Alexandre Ribot |

| Minister of Education | |

| In office 26 January 1895 – 1 November 1895 | |

| Prime Minister | Alexandre Ribot |

| Preceded by | Georges Leygues |

| Succeeded by | Émile Combes |

| In office 4 April 1893 – 3 December 1893 | |

| Prime Minister | Charles Dupuy |

| Preceded by | Charles Dupuy |

| Succeeded by | Eugène Spuller |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré 20 August 1860 Bar-le-Duc, France |

| Died | 15 October 1934 (aged 74) Paris, France |

| Political party | Democratic Republican Alliance |

| Spouse | |

| Alma mater | |

| Signature |  |

Trained in law, Poincaré was elected deputy in 1887 and served in the cabinets of Dupuy and Ribot. In 1902, he co-founded the Democratic Republican Alliance, the most important centre-right party under the Third Republic, becoming Prime Minister in 1912 and serving as President of the Republic from 1913 to 1920. He purged the French government of all opponents and critics and single-handedly controlled French foreign policy from 1912 to the beginning of World War I. He was noted for his strongly anti-German attitudes, shifting the Franco-Russian Alliance from the defensive to the offensive, visiting Russia in 1912 and 1914 to strengthen Franco-Russian relations, and giving France's support for Russian military mobilization during the July Crisis of 1914. From 1917, he exercised less influence as his political rival Georges Clemenceau had become prime minister. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, he advocated Allied occupation of the Rhineland for at least 30 years and French support for Rhenish separatism.

In 1922 Poincaré returned to power as Prime Minister. In 1923 he ordered the Occupation of the Ruhr to enforce payment of German reparations. By this time Poincaré was seen, especially in the English-speaking world, as an aggressive figure (Poincaré-la-Guerre) who had helped to cause the war in 1914 and who now favoured punitive anti-German policies. His government was defeated by the Cartel des Gauches at the elections of 1924. He served a third term as Prime Minister in 1926–1929. Poincaré was known by the title Le Lion in French.

Poincaré was an International Member of both the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[2][3]

Early years

Born in Bar-le-Duc, Meuse, France, Raymond Poincaré was the son of Nanine Marie Ficatier, who was deeply religious[4] and Nicolas Antonin Hélène Poincaré, a distinguished civil servant and meteorologist. Raymond was also the cousin of Henri Poincaré, the famous mathematician. He later wrote that "In all my years at school I saw no other reason to live than the possibility of recovering our lost provinces."[5] Educated at the University of Paris, Raymond was called to the Paris Bar, and was for some time law editor of the Voltaire. He became at the age of 20 the youngest lawyer in France.[6] and was appointed Secrétaire de la Conférence du Barreau de Paris. As a lawyer, he successfully defended Jules Verne in a libel suit presented against the famous author by the chemist, Eugène Turpin, inventor of the explosive melinite, who claimed that the "mad scientist" character in Verne's book Facing the Flag was based on him.[7] At the age of 26, Poincaré was elected to the Chamber of Deputies, making him the youngest deputy in the chamber.[6]

Early political career

Poincaré had served for over a year in the Department of Agriculture when in 1887 he was elected deputy for the Meuse département. He made a great reputation in the Chamber as an economist, and sat on the budget commissions of 1890–1891 and 1892. He was minister of education, fine arts and religion in the first cabinet (April – November 1893) of Charles Dupuy, and minister of finance in the second and third (May 1894 – January 1895). In Alexandre Ribot's cabinet, Poincaré became minister of public instruction. Although he was excluded from the Radical cabinet which followed, the revised scheme of death duties proposed by the new ministry was based upon his proposals of the previous year. He became vice-president of the chamber in the autumn of 1895 and, in spite of the bitter hostility of the Radicals, retained his position in 1896 and 1897.[8]

Along with other followers of "Opportunist" Léon Gambetta, Poincaré founded the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD) in 1902, which became the most important centre-right party under the Third Republic. In 1906, he returned to the ministry of finance in the short-lived Sarrien ministry. Poincaré had retained his practice at the Bar during his political career, and he published several volumes of essays on literary and political subjects.

"Poincarism" was a political movement over the period 1902–1920. In 1902, the term was used by Georges Clemenceau to define a young generation of conservative politicians who had lost the idealism of the founders of the republic. After 1911, the term was used to mean "national renewal" when faced with the German threat. After the First World War, "Poincarism" refers to his support of business and financial interests.[9] Poincaré was noted for his lifelong feud with Georges Clemenceau.[10]

First premiership

Poincaré became prime minister in January 1912 and systematically rooted out all political opponents and critics from the government, thereby securing total control over French foreign policy as both prime minister and later as president.[11] Foreign policy decisions during his time in cabinet were approved unanimously almost every time.[11] He viewed the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs as an administrative organ.[12] A Germanophobe, Poincaré ruled out any kind of understanding with Germany.[11] His Germanophobia was based not so much on revanchism but rather on his belief that Germany was too powerful and becoming stronger and the balance of power had to be changed through war in France's favor.[13] Poincaré sought to prevent any reconciliation between Germany and Britain or Russia.[14]

During the Bosnian Crisis of 1908-1909 and the Second Moroccan Crisis in 1911, France and the Russian Empire had failed to support each other.[15] In 1912, Poincaré converted the 1894 Franco-Russian Alliance from a defensive agreement to a tool for offensive war that could be triggered by a dispute in the Balkans.[11] In August 1912, Poincaré visited Tsar Nicholas in Russia to bolster France's military alliance with the Tsarist state.[16][17]

Poincaré hoped to pursue an expansionist policy at the expense of Germany's unofficial ally, the Ottoman Empire.[18] Poincaré was a leading member of the Comité de l'Orient, the main group that advocated French expansionism in the Middle East.[6] The victory of the Balkan League in the First Balkan War was seen by Poincaré as a powerful threat to Austria's flank, strengthening the Triple Entente and weakening the military position of Germany and Austria-Hungary.[19]

Poincaré rejected Joseph Caillaux's proposal for a Franco-German alliance, arguing that Paris would be the junior partner, thus tantamount to ending France's status as a great power.[20] A fiscal conservative, he was deeply concerned about the financial effects of an ever more costly arms race. Being from Lorraine, whether he was a revancharde (revanchist) is disputed.[21] His family house was requisitioned for three years during the war.[4]

Presidency

Pre-war

Poincaré won election as President of the Republic in 1913, in succession to Armand Fallières. His electoral victory was helped by some two million francs in Russian bribes to the French press.[5] The strong-willed Poincaré was the first president of the Third Republic since MacMahon in the 1870s to attempt to make that office into a site of power rather than an empty ceremonial role. During the Liman von Sanders crisis of 1913/1914, Poincaré anticipated war in two years and announced that "his entire effort is to prepare us for it".[22]

In early 1914, Poincaré found himself caught up in scandal when the leftish politician Joseph Caillaux threatened to publish letters showing that Poincaré was engaged in secret talks with the Vatican using the Italian government as an intermediary, which would have outraged anti-clerical opinion in France. Caillaux refrained from publishing the documents after the President pressured Gaston Calmette, editor of Le Figaro, not to publish documents showing that Caillaux had been unfaithful to his first wife, was involved in questionable financial dealings implicating a pro-German foreign policy. The matter might have remained settled had not the second Madame Caillaux, upset that Calmette might publish love letters written to her while her husband was still married to her predecessor, gone to Calmette's office on 16 March 1914 and shot him dead. The resulting scandal known as the Caillaux affair was the major French news story of the first half of 1914 causing Poincaré to joke that from now on he might send out Madame Poincaré to murder his political enemies since this method was working so well for Caillaux.[23]

World War I

On 28 June 1914, Poincaré was at the Longchamps racetrack when he received news of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.[24] Poincaré was fascinated by the report but stayed on to watch the race.[24]

In 1913, it had been announced that Poincaré would visit St. Petersburg in July 1914 to meet Tsar Nicholas II. Accompanied by Premier René Viviani, Poincaré went to Russia for the second time (but for the first time as president) to reinforce the Franco-Russian Alliance. On 15 July, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, Count Leopold von Berchtold, used a back channel to informed foreign countries of Austria-Hungary's intention to present an ultimatum to Serbia.[25] When Poincaré arrived in St. Petersburg on 20 July, the Russians told him by 21 July of the Austrian ultimatum and German support for Austria.[25] Although Prime Minister Viviani was supposed to be in charge of French foreign policy, Poincaré promised the Tsar unconditional French military backing for Russia against Austria-Hungary and Germany.[26] In his discussions with Nicholas II, Poincaré talked openly of winning an eventual war, not avoiding one.[22] Later, he attempted to hide his role in the outbreak of military conflict and denied having promised Russia anything.[22]

Poincaré arrived back in Paris on 29 July and at 7 am on 30 July, with Poincaré's full approval, Viviani sent a telegram to Nicholas affirming that:

in the precautionary measures and defensive measures to which Russia believes herself obliged to resort, she should not immediately proceed to any measure which might offer Germany a pretext for a total or partial mobilization of her forces.[27]

In his diary entry for the day, Poincaré wrote that the purpose of the message was not to prevent war from breaking out but to deny Germany a pretext and thereby obtain British support for the Franco-Russian alliance.[27] He approved of Russian mobilization.[27] A French covering force, five army corps strong, was deployed on the German border at 4:55 pm, as per normal premobilization procedure. Poincaré and Viviani demanded that the covering force be installed ten kilometers from the border, for the sole reason that France would look innocent in the eyes of Britain.[28] A note was immediately sent to London to tell the British about the maneuver and gain their sympathy against Germany.[29]

On 31 July the German ambassador in Paris, Count Wilhelm von Schoen, presented to Viviani a quasi-ultimatum warning that, if Russia did not end its mobilization within twelve hours, Germany would mobilize. Mobilization meant war.[30] That same day, the Chief of the General Staff of the French Army, General Joseph Joffre appealed for general mobilization, falsely claiming that Germany had been secretly mobilizing for two or three days.[31] Poincaré backed Joffre's request.[31] French general mobilization was decreed at 1600 hours on 1 August.[31] On 1 August, Poincaré lied to Francis Bertie, the British ambassador to France, claiming that Russian mobilization had only been decreed after Austria's.[32]

After Germany declared war on France on 3 August, Poincaré said: "Never was a declaration of war received with such satisfaction".[29] He appeared before the National Assembly at 3 pm on 4 August to announce that France was now at war forming the doctrine of the union sacrée in which he announced that: "nothing will break the union sacrée in the face of the enemy."[33] "Dans la guerre qui s'engage, la France […] sera héroïquement défendue par tous ses fils, dont rien ne brisera devant l'ennemi l'union sacrée" ("In the coming war, France will be heroically defended by all its sons, whose sacred union will not break in the face of the enemy"). During the meeting, Poincaré and Viviani were silent on Russia's mobilization, claiming instead that Russia had been negotiating to the end.[34]

Later war

Poincaré became increasingly sidelined after the accession to power of Georges Clemenceau as Prime Minister in 1917. He believed the Armistice happened too soon and that the French Army should have penetrated far deeper into Germany.[35] At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, he wanted France to wrest the Rhineland from Germany to put it under Allied military control.[36][37]

Ferdinand Foch urged Poincaré to invoke his powers as laid down in the constitution and take over the negotiations of the treaty due to worries that Clemenceau was not achieving France's aims.[38] He did not, and when the French Cabinet approved of the terms which Clemenceau obtained, Poincaré considered resigning, although again he refrained.[39]

Second premiership

In 1920, Poincaré's term as President came to an end, and two years later he returned to office as Prime Minister. Once again, his tenure was noted for its strong anti-German policies.[40]

Frustrated at Germany's unwillingness to pay reparations, Poincaré hoped for joint Anglo-French economic sanctions against it in 1922, while opposing military action. In April 1922, Poincare was greatly alarmed by the Treaty of Rapallo, the beginning of a German-Soviet challenge to the international order established by the Treaty of Versailles. He was disturbed that British Prime Minister David Lloyd George did not share the French viewpoint, instead almost welcoming Rapallo as a chance to bring Soviet Russia into the international system.[41] Poincaré came to believe by May 1922 that if Rapallo could not convince the British that Germany was out to undercut the Versailles system by whatever means necessary, then nothing would, in which case France would just have to act alone.[42] Further adding to Poincaré's fears was the worldwide propaganda campaign started in April 1922 blaming France for World War I as a means of disproving Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, which would thereby undermine the French claim to reparations.[43]

In the German-Soviet propaganda of the 1920s, the July Crisis of 1914 was portrayed as Poincaré-la-guerre (Poincaré's war), in which Poincaré put into action the plans he had allegedly negotiated with Emperor Nicholas II in 1912 for the dismemberment of Germany.[44] The French Communist newspaper L'Humanité ran a front-page cover-story accusing Poincaré and Nicholas II of being the two men who plunged the world into war in 1914.[45] The Poincaré-la-guerre propaganda proved to be very effective in the 1920s.[44]

Throughout the spring and summer of 1922, the British continued to spurn Poincaré's offers of an alliance with Britain.[42][46] Poincaré's attempt to compromise with the British on German reparations failed in 1922.[47] By December 1922 Poincaré was faced with British-American-German hostility and saw coal for French steel production and money for reconstructing the devastated industrial areas draining away.[48]

Poincaré decided to occupy the Ruhr on 11 January 1923, to extract the reparations himself. This, according to historian Sally Marks, "was profitable and caused neither the German hyperinflation, which began in 1922 and ballooned because of German responses to the Ruhr occupation, nor the franc's 1924 collapse, which arose from French financial practices and the evaporation of reparations."[49] The profits, after Ruhr-Rhineland occupation costs, were nearly 900 million gold marks.[50] During the Ruhr crisis, Poincaré made a failed attempt to establish diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union.[51][52] Poincaré lost the 1924 French legislative election "more from the franc's collapse and the ensuing taxation than from diplomatic isolation."[53]

Hines H. Hall argues that Poincaré was not a vindictive nationalist. Despite his disagreements with Britain, he desired to preserve the Anglo-French entente. When he ordered the French occupation of the Ruhr valley in 1923, his aims were moderate. He did not try to revive Rhenish separatism. His major goal was the winning of German compliance with the Versailles treaty. Poincaré's inflexible methods and authoritarian personality led to the failure of his diplomacy.[54]

Third premiership

Financial crisis brought him back to power in 1926, and he once again became Prime Minister and Finance Minister until his retirement in 1929. As Prime Minister, he enacted a number of franc stabilization policies, retroactively known as the Poincaré Stabilization Law.[55][56] His popularity as Prime Minister rose considerably following his return to the gold standard, so much so that his party won the April 1928 general election.[57]

As early as 1915, Raymond Poincaré introduced a controversial denaturalization law which was applied to naturalized French citizens with "enemy origins" who had continued to maintain their original nationality. Through another law passed in 1927, the government could denaturalize any new citizen who committed acts contrary to French "national interest".

Resignation and death

Due to his ill health, Poincaré resigned as Prime Minister in July 1929, refusing to serve another term as Prime Minister.[57] He died in Paris on 15 October 1934 at the age of 74.

Family

His brother, Lucien Poincaré (1862–1920), a physicist, became inspector-general of public instruction in 1902. He is the author of La Physique moderne (1906) and L'Électricité (1907).

Jules Henri Poincaré (1854–1912), an even more distinguished physicist and mathematician, was his first cousin.

Citations

- "Poincaré". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- "Raymond Poincare". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i et j Rémy Porte, "Raymond Poincaré, le président de la Grande Guerre", Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, no 88 de janvier-février 2017, p. 44-46

- McMeekin 2014, p. 66.

- Fromkin 2004, p. 80.

- A letter which Verne later sent to his brother Paul seems to suggest that, though acquitted due to Poincaré's spirited defence, Verne did intend to defame Turpin.

- Gooch, pp 137–151.

- J. F. V. Keiger, Raymond Poincaré (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p126

- Adamthwaite, Anthony Review of Raymond Poincaré by J. F. V. Keiger pages 491-492 from The English Historical Review, Volume 114, Issue 456, April 1999 page 491.

- Paddock 2019, p. 115.

- Paddock 2019, p. 124.

- Paddock 2019, p. 118.

- Paddock 2019, p. 119.

- Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 pages 369-370.

- McMeekin 2014, p. 67.

- Tomaszewski, Fiona "Pomp, Circumstance, and Realpolitik: The Evolution of the Triple Entente of Russia, Great Britain, and France" pages 362-380 from Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Volume 47, Issue # 3, 1999 pages 373-374.

- Fromkin 2004, p. 81.

- Paddock 2019, p. 120.

- Herwig, Holger & Hamilton, Richard Decisions for War, 1914-1917, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004 page 114.

- "Que dire de Poincaré ?". Mission Centenaire 14-18. 14 May 2022.

- Zuber 2014, p. 53.

- Fromkin 2004, p. 142-143.

- McMeekin 2014, p. 62.

- Zuber 2014, p. 52.

- Zuber 2014, pp. 52–53.

- McMeekin 2014, p. 295.

- McMeekin 2014, p. 305.

- Paddock 2019, p. 125.

- McMeekin 2014, p. 320.

- Zuber 2014, p. 61.

- McMeekin 2014, p. 356.

- Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Steéphane, & Becker, Annette France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 page 27.

- McMeekin 2014, p. 375.

- Margaret MacMillan, Peacemakers. The Paris Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War (John Murray, 2003), p. 42.

- MacMillan, p. 182.

- Ernest R. Troughton, It's Happening Again (London: John Gifford, 1944), p. 21.

- MacMillan, p. 212.

- MacMillan, p. 214.

- Étienne Mantoux, The Carthaginian Peace, or The Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes (London: Oxford University Press, 1946), p. 23.

- Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 288.

- Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 290.

- Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 291.

- Mombauer 2002, p. 200.

- Mombauer 2002, p. 94.

- Ephraim Maisel (1994). The Foreign Office and Foreign Policy, 1919-1926. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 122–23. ISBN 9781898723042.

- Keiger, John Raymond Poincaré, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002 pp. 291–293.

- Leopold Schwarzschild, World in Trance (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1943), p. 140.

- Sally Marks, '1918 and After. The Postwar Era', in Gordon Martel (ed.), The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered. Second Edition (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 26.

- Marks, p. 35, n. 57.

- Carley, Michael Jabara "Episodes from the Early Cold War: Franco-Soviet Relations, 1917-1927" 1275-1305 from Europe-Asia Studies, Volume 52, Issue #7, November 2000 pp. 1278-1279

- Carley, Michael Jabara "Episodes from the Early Cold War: Franco-Soviet Relations, 1917-1927" 1275-1305 from Europe-Asia Studies, Volume 52, Issue #7, November 2000 p. 1279

- Marks, p. 26.

- Hines H. Hall, III, "Poincare and Interwar Foreign Policy: 'L'Oublie de la Diplomatie' in Anglo-French Relations, 1922-1924," Proceedings of the Western Society for French History (1982), Vol. 10, pp. 485–494.

- Yee, Robert (2018). "The Bank of France and the Gold Dependency: Observations on the Bank's Weekly Balance Sheets and Reserves, 1898-1940" (PDF). Studies in Applied Economics. 128: 11.

- Makinen, Gail; Woodward, G. Thomas (1989). "A Monetary Interpretation of the Poincaré Stabilization of 1926". Southern Economic Journal. 56 (1): 191. doi:10.2307/1059066. JSTOR 1059066.

- "Raymond Poincaré". History.com. 21 August 2018.

Sources

- Adamthwaite, Anthony (April 1999). "Review of Raymond Poincaré by J. F. V. Keiger". The English Historical Review. 114 (456): 491–492. doi:10.1093/ehr/114.456.491.

- Fromkin, David (2004). Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Herwig, Holger & Richard Hamilton. Decisions for War, 1914-1917 (2004)

- Keiger, J. F. V. (1997). Raymond Poincaré. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57387-4., review

- Maisel, Ephraim (1994). The Foreign Office and Foreign Policy, 1919-1926. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 122–23.

- Marks, Sally '1918 and After. The Postwar Era', in Gordon Martel (ed.), The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 1999)

- McMeekin, Sean (2014). July 1914: Countdown to War. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465060740.

- Mombauer, Annika (2002). The Origins of the First World War. London: Pearson.

- Paddock, Troy R.E. (2019). Contesting the Origins of the First World War: An Historiographical Argument. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138308251.

- Smith, Leonard; Audoin-Rouzeau, Steéphane; Becker, Annette (2003). France and the Great War, 1914-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zuber, Terence (2014). "France and the Cause of World War I". Global War Studies. 11 (3): 51–63. doi:10.5893/19498489.11.03.03.

Further reading

- Bernard, Philippe, Henri Dubief & Thony Forster, The Decline of the Third Republic, 1914–1938, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985, oclc: 894680106

- Clark, Christopher, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, New York: Harper Collins, 2012.

- Gooch, G.P. Before the war: studies in diplomacy (2 vol 1936, 1938) online vol 2 pp 137–199.

- Keiger, John F. V. "Raymond Poincaré and the Ruhr crisis." French Foreign and Defence Policy, 1918-1940 (Routledge, 2005) pp. 59-80.

- Keiger, John F. V. Raymond Poincaré (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Mayeur, Jean-Marie, Madeleine Rebirioux & J. R. Foster, The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871-1914, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988

- Wright, Gordon, Raymond Poincare and the French Presidency, New York: Octagon Books, 1967, oclc: 405223

- Huddleston, Sisley, Poincaré: A Biographical Portrait,, Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1924

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Poincaré, Raymond". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Primary sources

- Poincaré, Raymond, The Origins of the War, London: Cassell, 1922, online

- Poincaré, Raymond, The memoirs of Raymond Poincare 1912 (1926) online

- Poincaré, Raymond, The Memoirs Of Raymond Poincare 1913-1914 (1928) online

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: The Day After Agadir, 1912 (Vol. I) online , in French

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: The Balkans on Fire, 1912 (Vol. II) online , in French

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: Europe Under Arms, 1913 (Vol. III) online , in French

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: The Sacred Union, 1914 (Vol. IV) online, in French

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: The Invasion, 1914 (Vol. V)

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: The Trenches, 1915 (Vol. VI)

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: Siege War, 1915 (Vol. VII online, in French

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: Verdun, 1916 (Vol. VIII)

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: The Troubled Year, 1917 (Vol. IX)

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: Victory and Armistice, 1918 (Vol. X)

- Poincaré, Raymond, In the Service of France: In Search of Peace, 1919 (Vol. XI)

External links

Quotations related to Raymond Poincaré at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Raymond Poincaré at Wikiquote- Works by or about Raymond Poincaré at Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about Raymond Poincaré in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW