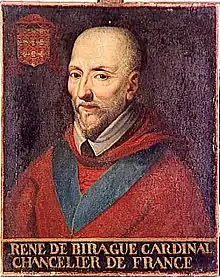

René de Birague

René de Birague (Italian: Renato da Birago; c. 1506–24 November 1583) was an Italian then French noble, lieutenant-general, chancellor and cardinal during the latter Italian Wars and the French Wars of Religion. Born to a prominent Milanese family in 1506, his family sided with the French, and as such when Milan was occupied by Emperor Charles V they were forced to flee to French controlled Piedmont. Declared a criminal in 1536, his Milanese estates would be seized. Birague entered French service in the 1540s, being elevated to premier président of the Parlement of Turin, which in combination with his service under the French governor Marshal Brissac from 1550, afforded him immense administrative power in the French occupied territories. In 1562 with the French withdrawal from the Piedmont, he departed his post in the Parlement, however the following year would see him elevated in one of the remaining French held towns, as leader of the Supreme Council of Pignerol.

René de Birague | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Lavaur Chancellor of France | |

| |

| In office | 1580-1583 |

| Orders | |

| Created cardinal | 21 February 1578 by Pope Gregory XIII |

| Rank | Cardinal-priest |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1506/7 |

| Died | 24 November 1583 Paris |

| Previous post(s) |

|

Moving into French service in France, he served as a diplomat in securing Charles IX's marriage to Elisabeth de Hapsburg in 1563. In 1565 he secured the unusual appointment as lieutenant-general of the Lyonnais, granting him military powers over the province and administrative in the absence of the governor. He deftly mobilised the town to provide large funds for a mercenary force during the second war of religion. In 1568 he was replaced as lieutenant-general by François de Mandelot. In 1568, Michel de l'Hôpital lost the seals of the Chancellorship, which went to Morvillier, in 1570 he in turn ceded them to Birague. As chancellor Birague enjoyed a rocky relationship with the Parlement. Birague was among the council that decided on the plan to liquidate the Protestant leadership in a pre-emptive strike, which would spiral out of control into the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew in 1572.

That same year, on the death of his wife, Birague began to consider a career in the church, taking up the post of Bishop of Lodève in 1573. Birague urged first Charles and then Henri III to take a harsh line against the prince's who plotted with the Malcontents in 1574-5. During the interregnum between Charles' death and the return of Henri to the kingdom, Birague led the regency council for Catherine de Medici. His advice was however ignored by the kings, and after the flight from court of Alençon, brother to the king, he was accused by the renegade prince of having tried to poison him, though there is no evidence of this. Alençon was able to successfully pressure the crown into a generous peace, and during the Estates General of 1576 that was called as a consequence, Henri dispatched Birague to beg the estates for money, to little effect. In 1578 Birague was relieved of the seals of the Chancellorship in favour of Philippe Hurault de Cheverny, though he would remain chancellor in a technical capacity until his death. That same year the king compensated him through generous financial contributions, and an appointment as cardinal. Made a commander in Henri's new Ordre du Saint-Esprit in 1580, he would join the 'white penitents' in March 1583, shortly before his death that same year.

Early life and family

Family

Birague came from a family of the Milanese nobility which had defected to French service during the reign of François I.[1] His father, Giangiacomo was of the prominent Galeazzo family, while his mother Anna came from the prominent Trivulzio family and was thus a relation of the French Marshal Teodoro Trivulzio.[2] Birague was born in 1506/7 in Milan.[3]

With the occupation of Milan by Emperor Charles V, many of the Birago retreated to Piedmont safely away from the Emperor. On 5 May 1536 the emperor declared that the nobility who had fled from Milan would be charged as criminals unless they returned immediately. Birague refused to return and as such his share of the Ottobiano fief was forfeit.[2]

He married Valentine Balbiani, from the town of Chieri, with whom he would stay until her death in June 1572.[4] Together they would have a daughter, who was married several times.[5]

Reputation and wealth

In 1577 he threatened the students of Poitiers, who he suspected had kidnapped his dog. He had a reputation for immense wealth, and he kept much of it with Italian bankers. Indeed the king entered contract with him on occasion for funds. He maintained a luxurious residence in Paris, from which he could entertain the court, before selling it to Marguerite de Valois in 1582.[5]

Reign of Henri II

Italian Wars

During the latter Italian Wars, Birague provided support to the French war effort in Italy from his base in Turin where he was the premier président in the Parlement, an office he would hold until the French vacation of Turin in 1562.[2] He wrote to Cardinal Lorraine with the ambition of keeping the French court appraised of developments on the peninsula. He had since 1547 been maître des requêtes of Vizelle.[6] In 1550, Marshal Brissac assumed authority as lieutenant-general of the Piedmont. To support him in this strategic office, Birague took charge of the civil administration of those areas under French control, while Vimercato provided local military leadership.[7] The following year he was involved in the negotiations that saw the surrender of Chieri to the French, after a siege by Brissac.[2]

Heresy

Birague used his authority in Piedmont to suppress and persecute the Waldensians, this aroused the concern of the council of Bern, which wrote to Brissac to protest Birague's actions. Brissac did little in response, as Birague's actions were in agreement with the policy of the king.[2]

Reign of Charles IX

Pignerol

As the crisis of the civil wars deepened with the fall of many major towns to the Protestant rebels, it was decided that it would serve the crowns interests well to secure the friendship of the duke of Savoy. To this end Catherine decided that several towns that the French had held onto in the Piedmont at the end of the Italian Wars would be ceded to the duke. Bourdillon lieutenant general of Piedmont, Morvillier, Alluye and Birague were entrusted with the commission to oversee the transfer of the settlements. Bourdillion refused his role, arguing that as the king was a minor such a transfer could not take place. Bourdillion was eventually bought off from his opposition by an offer of the marshalate, allowing the transfer to go ahead.[8] One of the towns that France maintained authority over was Pignerol. A council was set up to govern this territory, with Birague at its head in June 1563. During that same year he travelled to Wien to secure the marriage negotiations between Charles IX and Elizabeth de Hapsburg.[2]

Lyonnais

In 1565, Birague was elevated to the position of lieutenant-general of the Lyonnais, giving him authority over the military situation in the province and the powers of governor in the absence of Jacques, Duke of Nemours. This was an unusual appointment for a member of the administrative nobility, but not unheard of.[9] At the outbreak of the second war of religion, he mobilised the Catholic notables of Lyon to provide a forced loan to defend the town against an attempted Protestant seizure. He authorised the confiscation of Protestant property and the re-selling of it to raise more funds. By this means he raised 174,000 livres with which he raised four mercenary companies under the command of Chambery.[10] Throughout his tenure in the Lyonnais Birague sought to repress Protestantism with the support of the commissars under his authority.[11] He was replaced as lieutenant-general by François de Mandelot in 1568.[2] During the 1560s Birague also entered the king's council, representing hardliner Catholic positions.[12]

Chancellor

His policy of conciliation and tolerance of Protestantism increasingly falling out of favour, Michel de l'Hôpital surrendered the seals of the chancellorship in September 1568, unwilling to use them to renew the civil wars. In his place as keeper of the seals, the king turned to Morvillier a more reliable protégé of Catherine.[13] That same year another fidèle of Catherine entered the royal council, Birague.[14] Morvillier in turn returned the seals in 1570, disgusted at the king's willingness to release the duke of Lorraine from the fealty he owed the crown of France for the Duchy of Bar. Birague became garde des sceaux, giving him the de facto powers of chancellor, he was formerly appointed to the office of chancellor in 1573 upon the death of Hôpital.[15][14][16][2] As chancellor he would not exert the same influence on the administration as his predecessor Hôpital had.[1] Some commentators criticised his administration due to the poor relations it enjoyed with the Parlement of Paris.[5]

Birague was selected by Catherine to play an important role in the negotiations for a marriage between Marguerite de Valois and Navarre. The marriage was intended by Catherine as a cornerstone of the reconciliation envision by the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye which had brought the third war of religion to a close, uniting the Bourbon's with the Valois. Alongside Morvilliers and Foix he was entrusted to represent her in the discussions with Jeanne d'Albret. By April 1572 the marriage was successfully agreed.[17] Birague and Foix were also tasked with conducting preliminary negotiations with England for an anti-Spanish alliance, while this did result in the Treaty of Blois in May 1572, it would not lead to a combined war against Spain.[18] Indeed Birague was opposed to a war, and with Admiral Coligny attempting to push the king into declaring one over the Spanish Netherlands, he and Retz proceeded to Catherine who was absent from court, ensuring she hurried back to oppose any moves against Spain.[19]

Massacre of Saint Bartholomew

Shortly after the marriage celebrations of Navarre and Marguerite, there was an attempt on Admiral Coligny's life. As the military leader of the Protestants threats abounded in the capital about potential retribution. Birague was a zealous advocate of royal authority, and the idea that Protestant nobles might take justice into their own hands unnerved him.[20] Catherine met with her leading advisers, Retz, Nevers, Tavannes and Birague. Together the council agreed that it was necessary to sever the head of the Protestant leadership in Paris to avoid a civil war. Their plan would go awry however, and the assassinations would spiral into the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew's Day.[21] Many saw in the massacre the 'demonic influence' of foreigners on the court of France. With the Italians Catherine, Retz, Birague and Nevers accused of having brought about the civil wars of the past decade as a way of destroying the upper nobility of France.[16]

The death of his wife in 1572 had pushed Birague into a new direction for his career, and he considered taking up holy orders. In October 1573 he became Bishop of Lodève, and ring fenced his diocese from a round of alienations that occurred that year.[5]

Malcontents

Faced with the Malcontents who though Catholic had entered conspiracy against the crown in 1574, Birague urged the king to follow a harsh course of justice. He proposed to Charles that while it was important to show clemency at times, traitors who threatened the kingdom with ruin such as Marshal Montmorency needed to be treated in the 'manner of Louis XI', i.e. arrested. The king and his mother were ill inclined to follow this course with such a powerful noble, and he was kept under loose surveillance until their hand was forced by a further attempted conspiracy. Now locked in the Bastille the crown hoped the threat of a potential execution would keep the duke's brothers who were with a mercenary force in Germany from invading the kingdom.[22][23]

Reign of Henri III

Fifth civil war

Montmorency's other brother Damville, governor of Languedoc who had entered rebellion in the south in favour of his brother was approached by Cardinal Bourbon in October 1574 to try and bring him back into allegiance with the crown. Damville responded with a series of conditions for his return to loyalty, one of which was that Henri III dismiss the foreigners in his midst, mentioning the Italian Birague and Retz by name as a destructive influence on the kingdom.[24][25] During the absence of Henri from the kingdom, Catherine governed as regent, as had been the request of Charles on his deathbed. To assist her in governing the kingdom, she looked to her favourite Birague for support.[26] Birague chaired the royal council in the king's absence.[27]

With Henri returning from the Commonwealth to assume the French crown he passed through the city of Turin on his travels. While there he was taken aside by the duke of Savoy, who convinced him to return the remaining French held towns in the Piedmont. Birague reacted with horror to this abdication of France's position in Italy, and refused to put his seals to the decision upon Henri's arrival. Nevers, who governed French Piedmont joined Birague in the denunciation, insisting his disapproval be formerly registered.[28][29]

Alençon

At the advent of Henri's reign, Birague was one of eight members of the conseil privé et d'état, alongside Morvillier, Cheverny and Bellièvre among others.[30] Birague advised the recently returned king to keep his brother Alençon and cousin Navarre under arrest to stop them from joining any rebellions, the king however allowed them to move as they pleased though under a degree of surveillance.[25] Alençon who had been flirting with joining the Malcontents since the original conspiracy, declared his hand in September 1575 and fled court to put himself at the head of the rebellion. From Dreux he laid out his manifesto, one component of which was a denunciation of the monopoly on high office enjoyed by Italians, who should be expelled from the kingdom, he mentioned Birague specifically.[31] Recognising the danger of the situation to the crown's authority, a generous truce was agreed in November, hoping to detach Alençon from the other rebels to whom he provided considerable legitimacy.

Hatred of Italians was not restricted to the upper nobility, in July 1575, after the murder of a student in Paris by an Italian, riots broke out against the presence of Italians in the city. As the violence escalated, Birague was singled out for abuse in the pamphlets of Paris as a corrosive influence on the country.[32]

Poisoned wine

On 26 December Alençon and some friends were enjoying some wine when they became sick, keen to see conspiracy he blamed the sommelier for poisoning his wine. The mastermind of this conspiracy was to be Birague, who had formerly employed the sommelier. No evidence of poisoning was found.[33] In January 1576 Alençon repudiated the truce, linking up with forces under the Protestant Turenne. The king was forced into a favourable peace towards the Protestants to bring the civil war to a close on 6 May in the Peace of Monsieur.[34]

As a term of the peace Henri called an Estates General, this Estates was dominated by militant Catholics who wanted to overturn the recent peace and decisively crush Protestantism. Henri, having now secured the loyalty of his brother was open to doing away with the peace that he had felt forced to make, however he required funds to fight a war. To this end Birague was sent to the Estates to deliver an address, this took the form of a harangue in which he critiqued each estate for their lack of unity and expounded on how this had caused the crises that faced the kingdom in the past decade. He blamed the poverty of the crown on the irresponsibility of previous administrations, and informed the estates that it was their duty to provide money to allow the king to rebuild the royal army.[35] His speech was the subject of mockery, due to his ineloquent presentation in comparison with the king.[5] With civil war resumed, Birague was among those dispatched again to the estates in January 1577 to beg the estates to provide more funds. The king was unable to achieve notable success in this fundraising effort.[36]

Cardinal

In 1578 Birague received appointment as Cardinal upon the recommendation of the king.[5] That same year he lost his authority as Chancellor of France when the seals were transferred to Cheverny. As was often the case with the office, though he no longer held the authority of the office, Cheverny would not succeed him as Chancellor until his death.[37] To compensate him Henri provided benefices of a value of 70,000 livres and another 30,000 livres to support his office of chancellor, despite no longer having its powers.[38] Around the same time Catherine's influence on the court began to decline. Birague and Retz would continue to loyally represent her positions on court in her absence.[39]

When the king founded his new Ordre du Saint-Esprit, to replace the Order of Saint-Michel, Birague was among the early intakes as a commander. By 1582 he had determined to retire from public life, selling his Parisian hôtel, and retiring to his priory. In March 1583 he joined the newly founded order of the White Penitents.[5]

In the 1583 Assembly of Notables, Cheverny stood in for Birague, who would as nominal chancellor be expected to give a speech to the grandees, as Birague was on deaths door.[40] During Birague's funeral in December 1583, Henri attended, dressed as a penitent.[41] The white penitents at large accompanied his body, while the Archbishop of Bourges gave the oration. His tomb, which he shared with his wife would be designed by Germain Pilon.[5]

His fortune passed to his male relatives, as he little trusted his daughter.[5]

Sources

- Carroll, Stuart (2005). Noble Power during the French Wars of Religion: The Guise Affinity and the Catholic Cause in Normandy. Cambridge University Press.

- Cloulas, Ivan (1985). Henri II. Fayard.

- Durot, Éric (2012). François de Lorraine, duc de Guise entre Dieu et le Roi. Classiques Garnier.

- Harding, Robert (1978). Anatomy of a Power Elite: the Provincial Governors in Early Modern France. Yale University Press.

- Holt, Mack (2002). The Duke of Anjou and the Politique Struggle During the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press.

- Jouanna, Arlette (1998). Histoire et Dictionnaire des Guerres de Religion. Bouquins.

- Jouanna, Arlette (2007). The St Bartholomew's Day Massacre: The Mysteries of a Crime of State. Manchester University Press.

- Knecht, Robert (2014). Catherine de' Medici. Routledge.

- Knecht, Robert (2016). Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-1589. Routledge.

- Miranda, Salvador. "BIRAGUE, René de (1506-1583)". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Florida International University. OCLC 53276621.

- Roelker, Nancy (1968). Queen of Navarre: Jeanne d'Albret 1528-1572. Harvard University Press.

- Salmon, J.H.M (1975). Society in Crisis: France during the Sixteenth Century. Metheun & Co.

- Shimizu, J. (1970). Conflict of Loyalties: Politics and Religion in the Career of Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of France, 1519–1572. Geneva: Librairie Droz.

- Sutherland, Nicola (1962). The French Secretaries of State in the Age of Catherine de Medici. The Athlone Press.

- Thompson, James (1909). The Wars of Religion in France 1559-1576: The Huguenots, Catherine de Medici and Philip II. Chicago University Press.

References

- Salmon 1975, p. 218.

- Jouanna 1998, p. 727.

- Jouanna 1998, p. 1482.

- Jouanna 1998, pp. 727–728.

- Jouanna 1998, p. 728.

- Durot 2012, p. 135.

- Cloulas 1985, p. 184.

- Sutherland 1962, pp. 129–132.

- Harding 1978, p. 69, 134.

- Harding 1978, p. 104.

- Harding 1978, p. 198.

- Knecht 2014, p. 96.

- Thompson 1909, p. 367.

- Carroll 2005, p. 134.

- Thompson 1909, p. 425.

- Jouanna 2007, p. 207.

- Roelker 1968, p. 372, 382.

- Shimizu 1970, p. 158.

- Knecht 2014, p. 152.

- Jouanna 2007, p. 102.

- Carroll 2005, p. 136.

- Thompson 1909, p. 479.

- Holt 2002, p. 56.

- Thompson 1909, p. 492.

- Holt 2002, p. 46.

- Holt 2002, p. 45.

- Knecht 2016, p. 100.

- Knecht 2014, p. 175.

- Knecht 2016, p. 96.

- Salmon 1975, p. 219.

- Holt 2002, p. 52.

- Holt 2002, p. 49.

- Holt 2002, p. 61.

- Knecht 2014, pp. 181–184.

- Holt 2002, pp. 77–78.

- Holt 2002, pp. 82–83.

- Salmon 1975, p. 67, 218.

- Jouanna 1998, p. 1998.

- Knecht 2016, p. 139.

- Knecht 2016, p. 223.

- Sutherland 1962, p. 247.