Teenage pregnancy

Teenage pregnancy, also known as adolescent pregnancy, is pregnancy in a female adolescent under the age of 20. This includes those who are legally considered adults in their country.[2] The WHO defines adolescence as the period between the ages of 10 and 19 years.[5] Pregnancy can occur with sexual intercourse after the start of ovulation, which can happen before the first menstrual period (menarche).[6] In healthy, well-nourished girls, the first period usually takes place between the ages of 13 to 16.[7]

| Teenage pregnancy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Teen pregnancy, adolescent pregnancy |

| |

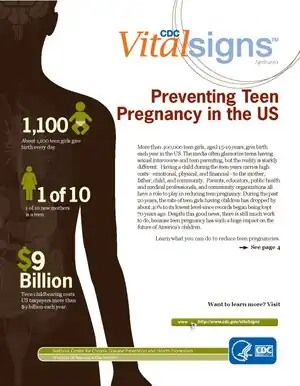

| A US government poster on teen pregnancy. Over 1,100 teenagers, mostly aged 18 or 19,[1] give birth every day in the United States. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Symptoms | Pregnancy under the age of 20[2] |

| Complications | |

| Prevention | |

| Frequency | 23 million per year (developed world)[3] |

| Deaths | Leading cause of death (15 to 19 year old females)[3] |

Pregnant teenagers face many of the same pregnancy-related issues as older women. There are additional concerns for those under the age of 15 as they are less likely to be physically developed to sustain a healthy pregnancy or to give birth.[8] For girls aged 15–19, risks are associated more with socioeconomic factors than with the biological effects of age.[9] Risks of low birth weight, premature labor, anemia, and pre-eclampsia are not connected to biological age by the time a girl is 16, as they are not observed in births to older teens after controlling for other risk factors, such as access to high-quality prenatal care.[10][11]

Teenage pregnancies are related to social issues, including lower educational levels and poverty.[3] Teenage pregnancy in developed countries is usually outside of marriage and is often associated with a social stigma.[12] Teenage pregnancy in developing countries often occurs within marriage and half are planned.[3] However, in these societies, early pregnancy may combine with malnutrition and poor health care to cause medical problems. When used in combination, educational interventions and access to birth control can reduce unintended teenage pregnancies.[4][13]

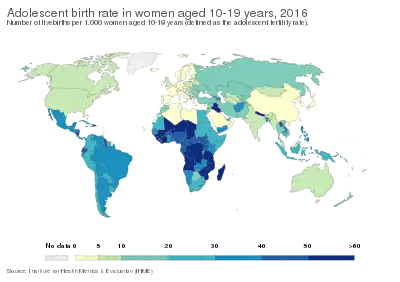

In 2023, about 41 females age per 1,000 had children between the ages of 15 and 19, as compared with roughly 65 births per 1000 in 2000.[14] From 2015 to 2021, an estimated 14 percent of adolescent girls and young women globally reported giving birth before age 18.[15] Rates have historically been higher in Africa and lower in Asia.[3] In the developing world about 2.5 million females under the age of 16 and 16 million females 15 to 19 years old have children each year.[3] Another 3.9 million have abortions.[3] It is more common in rural than urban areas.[3] Worldwide, complications related to pregnancy are the most common cause of death among females 15 to 19 years old.[3]

In 2021, 13.3 million babies, or about 10 percent of the total worldwide, were born to mothers under 20 years old.[16]

Definition

The World Health Organization defines adolescence as the period between the ages of 10 and 19 years.[5]

The mother's age is determined by the easily verified date when the pregnancy ends, not by the estimated date of conception.[18] Consequently, the statistics do not include pregnancies that began at age 19, but that ended on or after the woman's 20th birthday.[18] Similarly, statistics on the mother's marital status are determined by whether she is married at the end of the pregnancy, not at the time of conception.[19]

History

Teenage pregnancy (with conceptions normally involving girls between ages 16 and 19) was far more normal in previous centuries, and common in developed countries in the 20th century. Among Norwegian women born in the early 1950s, nearly a quarter became teenage mothers by the early 1970s. However, the rates have steadily declined throughout the developed world since that 20th-century peak. Among those born in Norway in the late 1970s, less than 10% became teenage mothers, and rates have fallen since then.[20][21]

In the United States, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996 included the objective of reducing the number of young Black and Latina single mothers on welfare, which became the foundation for teenage pregnancy prevention in the United States and the founding of the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, now known as Power to Decide.[22]

Effects

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), "Pregnancies among girls less than 18 years of age have irreparable consequences. It violates the rights of girls, with life-threatening consequences in terms of sexual and reproductive health, and poses high development costs for communities, particularly in perpetuating the cycle of poverty."[23] Health consequences include not yet being physically ready for pregnancy and childbirth leading to complications and malnutrition as the majority of adolescents tend to come from lower-income households. The risk of maternal death for girls under age 15 in low and middle income countries is higher than for women in their twenties.[23] Teenage pregnancy also affects girls' education and income potential as many are forced to drop out of school which ultimately threatens future opportunities and economic prospects.[24]

Several studies have examined the socioeconomic, medical, and psychological impact of pregnancy and parenthood in teens. Life outcomes for teenage mothers and their children vary; other factors, such as poverty or social support, may be more important than the age of the mother at the birth. Many solutions to counteract the more negative findings have been proposed. Teenage parents who can rely on family and community support, social services and child-care support are more likely to continue their education and get higher paying jobs as they progress with their education.[25][26]

A holistic approach is required in order to address teenage pregnancy. This means not focusing on changing the behaviour of girls but addressing the underlying reasons of adolescent pregnancy such as poverty, gender inequality, social pressures and coercion. This approach should include "providing age-appropriate comprehensive sexuality education for all young people, investing in girls' education, preventing child marriage, sexual violence and coercion, building gender-equitable societies by empowering girls and engaging men and boys and ensuring adolescents' access to sexual and reproductive health information as well as services that welcome them and facilitate their choices".[24]

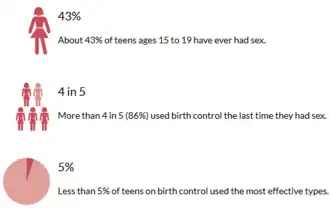

In the United States one third of high school students reported being sexually active. In 2011–2013, 79% of females reported using birth control. Teenage pregnancy puts young women at risk for health issues, economic, social and financial issues.[27][28]

Teenager

Being a young mother in a first world country can affect one's education. Teen mothers are more likely to drop out of high school.[29] One study in 2001 found that women that gave birth during their teens completed secondary-level schooling 10–12% as often and pursued post-secondary education 14–29% as often as women who waited until age 30.[30] Young motherhood in an industrialized country can affect employment and social class. Teenage women who are pregnant or mothers are seven times more likely to commit suicide than other teenagers.[31]

According to the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, nearly 1 in 4 teen mothers will experience another pregnancy within two years of having their first.[32] Pregnancy and giving birth significantly increases the chance that these mothers will become high school dropouts and as many as half have to go on welfare. Many teen parents do not have the intellectual or emotional maturity that is needed to provide for another life.[33] Often, these pregnancies are hidden for months resulting in a lack of adequate prenatal care and dangerous outcomes for the babies.[33] Factors that determine which mothers are more likely to have a closely spaced repeat birth include marriage and education: the likelihood decreases with the level of education of the young woman – or her parents – and increases if she gets married.[34]

Child

Early motherhood can affect the psychosocial development of the infant. The children of teen mothers are more likely to be born prematurely with a low birth weight, predisposing them to many other lifelong conditions.[35] Children of teen mothers are at higher risk of intellectual, language, and socio-emotional delays.[33] Developmental disabilities and behavioral issues are increased in children born to teen mothers.[36][37] One study suggested that adolescent mothers are less likely to stimulate their infant through affectionate behaviors such as touch, smiling, and verbal communication, or to be sensitive and accepting toward their needs.[36] Another found that those who had more social support were less likely to show anger toward their children or to rely upon punishment.[38]

Poor academic performance in the children of teenage mothers has also been noted, with many of the children being held back a grade level, scoring lower on standardized tests, and/or failing to graduate from secondary school.[29] Daughters born to adolescent parents are more likely to become teen mothers themselves.[29][39] Sons born to teenage mothers are three times more likely to serve time in prison.[40]

Prenatal care

Maternal and prenatal health is of particular concern among teens who are pregnant or parenting. The worldwide incidence of premature birth and low birth weight is higher among adolescent mothers.[9][29][41] In a rural hospital in West Bengal, teenage mothers between 15 and 19 years old were more likely to have anemia, preterm delivery, and a baby with a lower birth weight than mothers between 20 and 24 years old.[42]

Research indicates that pregnant teens are less likely to receive prenatal care, often seeking it in the third trimester, if at all.[9] The Guttmacher Institute reports that one-third of pregnant teens receive insufficient prenatal care and that their children are more likely to have health issues in childhood or be hospitalized than those born to older women.[43]

In the United States, teenage Latinas who become pregnant face barriers to receiving healthcare because they are the least insured group in the country.[44]

Young mothers who are given high-quality maternity care have significantly healthier babies than those who do not. Many of the health-issues associated with teenage mothers appear to result from lack of access to adequate medical care.[45]

Many pregnant teens are at risk of nutritional deficiencies from poor eating habits common in adolescence, including attempts to lose weight through dieting, skipping meals, food faddism, snacking, and consumption of fast food.[46]

Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy is an even more marked problem among teenagers in developing countries.[47][48] Complications of pregnancy result in the deaths of an estimated 70,000 teen girls in developing countries each year. Young mothers and their babies are also at greater risk of contracting HIV.[8] The World Health Organization estimates that the risk of death following pregnancy is twice as high for girls aged 15–19 than for women aged 20–24. The maternal mortality rate can be up to five times higher for girls aged 10–14 than for women aged 20–24. Illegal abortion also holds many risks for teenage girls in areas such as sub-Saharan Africa.[49]

Risks for medical complications are greater for girls aged under 15, as an underdeveloped pelvis can lead to difficulties in childbirth. Obstructed labour is normally dealt with by caesarean section in industrialized nations; however, in developing regions where medical services might be unavailable, it can lead to eclampsia, obstetric fistula, infant mortality, or maternal death.[8][24] For mothers who are older than fifteen, age in itself is not a risk factor, and poor outcomes are associated more with socioeconomic factors rather than with biology.[9]

Antenatal care

As of 2023, UNICEF noted that:

84 percent of pregnant adolescents aged 15-19 attended at least one antenatal care visit as compared to 88 percent of all women and girls aged 15-49. Fewer adolescent girls received skilled delivery care as compared to all women and girls (77 to 84 percent). Additionally, fewer adolescent girls received postnatal care for themselves as compared to all women and girls (66 percent vs 69 percent).[50]

The agency further noted regional disparities, noting that in West and Central Africa, "48 percent of newborns to adolescent mothers had a postnatal contact as compared to 52 percent of newborns to all mothers".[50]

Economics

The lifetime opportunity cost caused by teenage pregnancy in different countries varies from 1% to 30% of the annual GDP (30% being the figure in Uganda).[51] In the United States, teenage pregnancy costs taxpayers between $9.4 and $28 billion each year, due to factors such as foster care and lost tax revenue.[52] The estimated increase in economic productivity from ending teenage pregnancy in Brazil and India would be over $3.5 billion and $7.7 billion respectively.[51]

Less than one third of teenage mothers receive any form of child support, vastly increasing the likelihood of turning to the government for assistance.[53] The correlation between earlier childbearing and failure to complete high school reduces career opportunities for many young women.[29] One study found that, in 1988, 60% of teenage mothers were impoverished at the time of giving birth.[54] Additional research found that nearly 50% of all adolescent mothers sought social assistance within the first five years of their child's life.[29] A study of 100 teenaged mothers in the UK found that only 11% received a salary, while the remaining 89% were unemployed.[55] Most British teenage mothers live in poverty, with nearly half in the bottom fifth of the income distribution.[56]

Risk factors

Culture

Rates of teenage pregnancies are higher in societies where it is traditional for girls to marry young and where they are encouraged to bear children as soon as they are able. For example, in some sub-Saharan African countries, early pregnancy is often seen as a blessing because it is proof of the young woman's fertility.[49] Countries where teenage marriages are common experience higher levels of teenage pregnancies. In the Indian subcontinent, early marriage and pregnancy is more common in traditional rural communities than in cities.[57] Many teenagers are not taught about methods of birth control and how to deal with peers who pressure them into having sex before they are ready. Many pregnant teenagers do not have any cognition of the central facts of sexuality.[58]

Economic incentives also influence the decision to have children. In societies where children are set to work at an early age, it is economically attractive to have many children.[59]

In societies where adolescent marriage is less common, such as many developed countries, young age at first intercourse and lack of use of contraceptive methods (or their inconsistent and/or incorrect use; the use of a method with a high failure rate is also a problem) may be factors in teen pregnancy.[60][61] Most teenage pregnancies in the developed world appear to be unplanned.[61][62] Many Western countries have instituted sex education programs, the main objective of which is to reduce unplanned pregnancies and STIs. Countries with low levels of teenagers giving birth accept sexual relationships among teenagers and provide comprehensive and balanced information about sexuality.[63]

Teenage pregnancies are common among Romani people because they marry earlier.[64]

Other family members

Teen pregnancy and motherhood can influence younger siblings. One study found that the younger sisters of teen mothers were less likely to emphasize the importance of education and employment and more likely to accept human sexual behavior, parenting, and marriage at younger ages. Younger brothers, too, were found to be more tolerant of non-marital and early births, in addition to being more susceptible to high-risk behaviors.[65] If the younger sisters of teenage parents babysit the children, they have an increased probability of getting pregnant themselves.[66] Once an older daughter has a child, parents often become more accepting as time goes by.[67] A study from Norway in 2011 found that the probability of a younger sister having a teenage pregnancy went from 1:5 to 2:5 if the elder sister had a baby as a teenager.[68]

Sexuality

In most countries, most males experience sexual intercourse for the first time before their 20th birthday.[69] Males in Western developed countries have sex for the first time sooner than in undeveloped and culturally conservative countries such as sub-Saharan Africa and much of Asia.[69]

In a 2005 Kaiser Family Foundation study of US teenagers, 29% of teens reported feeling pressure to have sex, 33% of sexually active teens reported "being in a relationship where they felt things were moving too fast sexually", and 24% had "done something sexual they didn't really want to do".[70] Several polls have indicated peer pressure as a factor in encouraging both girls and boys to have sex.[71][72] The increased sexual activity among adolescents is manifested in increased teenage pregnancies and an increase in sexually transmitted diseases.

Role of drug and alcohol use

Inhibition-reducing drugs and alcohol may possibly encourage unintended sexual activity.[73] If so, it is unknown if the drugs themselves directly influence teenagers to engage in riskier behavior, or whether teenagers who engage in drug use are more likely to engage in sex. Correlation does not imply causation. The drugs with the strongest evidence linking them to teenage pregnancy are alcohol, cannabis, "ecstasy" and other substituted amphetamines. The drugs with the least evidence to support a link to early pregnancy are opioids, such as heroin, morphine, and oxycodone, of which a well-known effect is the significant reduction of libido – it appears that teenage opioid users have significantly reduced rates of conception compared to their non-using, and alcohol, "ecstasy", cannabis, and amphetamine using peers.[60][70][74][75]

Early puberty

Girls who mature early (precocious puberty) are more likely to engage in sexual intercourse at a younger age, which in turn puts them at greater risk of teenage pregnancy.[76]

Lack of contraception

Adolescents may lack knowledge of, or access to, conventional methods of preventing pregnancy, as they may be too embarrassed or frightened to seek such information.[71][77] Contraception for teenagers presents a huge challenge for the clinician. In 1998, the government of the UK set a target to halve the under-18 pregnancy rate by 2010. The Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (TPS) was established to achieve this. The pregnancy rate in this group, although falling, rose slightly in 2007, to 41.7 per 1,000 women. Young women often think of contraception either as 'the pill' or condoms and have little knowledge about other methods. They are heavily influenced by negative, second-hand stories about methods of contraception from their friends and the media. Prejudices are extremely difficult to overcome. Over concern about side-effects, for example weight gain and acne, often affect choice. Missing up to three pills a month is common, and in this age group the figure is likely to be higher. Restarting after the pill-free week, having to hide pills, drug interactions and difficulty getting repeat prescriptions can all lead to method failure.[78]

In the US, according to the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, sexually active adolescent women wishing to avoid pregnancy were less likely than older women to use contraceptives (18% of 15–19-year-olds used no contraceptives, versus 10.7% for women aged 15–44).[79] More than 80% of teen pregnancies are unintended.[80] Over half of unintended pregnancies were to women not using contraceptives,[79] most of the rest are due to inconsistent or incorrect use.[80] 23% of sexually active young women in a 1996 Seventeen magazine poll admitted to having had unprotected sex with a partner who did not use a condom, while 70% of girls in a 1997 PARADE poll claimed it was embarrassing to buy birth control or request information from a doctor.[71]

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health surveyed 1027 students in the US in grades 7–12 in 1995 to compare the use of contraceptives among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. The results were that 36.2% of Hispanics said they never used contraception during intercourse which is a high rate compared to 23.3% of Black teens and 17.0% of White teens who also did not use contraceptives during intercourse.[44]

In a 2012 study, over 1,000 females were surveyed to find out factors contributing to not using contraception. Of those surveyed, almost half had been involved in unprotected sex within the previous three months. These women gave three main reasons for not using contraceptives: trouble obtaining birth control (the most frequent reason), lack of intention to have sex, and the misconception that they "could not get pregnant".[81]

In a study for the Guttmacher Institute, researchers found that from a comparative perspective, however, teenage pregnancy rates in the US are less nuanced than one might initially assume. "Since timing and levels of sexual activity are quite similar across [Sweden, France, Canada, Great Britain, and the US], the high U.S. rates arise primarily because of less, and possibly less-effective, contraceptive use by sexually active teenagers."[82] Thus, the cause for the discrepancy between rich nations can be traced largely to contraceptive-based issues.

Among teens in the UK seeking an abortion, a study found that the rate of contraceptive use was roughly the same for teens as for older women.[83]

In other cases, contraception is used, but proves to be inadequate. Inexperienced adolescents may use condoms incorrectly, forget to take oral contraceptives, or fail to use the contraceptives they had previously chosen. Contraceptive failure rates are higher for teenagers, particularly poor ones, than for older users.[74] Long-acting contraceptives such as intrauterine devices, subcutaneous contraceptive implants, and contraceptive injections (such as Depo-Provera and combined injectable contraceptive), which prevent pregnancy for months or years at a time, are more effective in women who have trouble remembering to take pills or using barrier methods consistently.

According to Encyclopedia of Women's Health, published in 2004, there has been an increased effort to provide contraception to adolescents via family planning services and school-based health, such as HIV prevention education.[84]

Sexual abuse

Studies from South Africa have found that 11–20% of pregnancies in teenagers are a direct result of rape, while about 60% of teenage mothers had unwanted sexual experiences preceding their pregnancy. Before age 15, a majority of first-intercourse experiences among females are reported to be non-voluntary; the Guttmacher Institute found that 60% of girls who had sex before age 15 were coerced by males who on average were six years their senior.[85] One in five teenage fathers admitted to forcing girls to have sex with them.[86]

Multiple studies have indicated a strong link between early childhood sexual abuse and subsequent teenage pregnancy in industrialized countries. Up to 70% of women who gave birth in their teens were molested as young girls; by contrast, 25% of women who did not give birth as teens were molested.[87][88][89]

In some countries, sexual intercourse between a minor and an adult is not considered consensual under the law because a minor is believed to lack the maturity and competence to make an informed decision to engage in fully consensual sex with an adult. In those countries, sex with a minor is therefore considered statutory rape. In most European countries, by contrast, once an adolescent has reached the age of consent, he or she can legally have sexual relations with adults because it is held that in general (although certain limitations may still apply), reaching the age of consent enables a juvenile to consent to sex with any partner who has also reached that age. Therefore, the definition of statutory rape is limited to sex with a person under the minimum age of consent. What constitutes statutory rape ultimately differs by jurisdiction (see age of consent).

Dating violence

Studies have indicated that adolescent girls are often in abusive relationships at the time of their conceiving.[90][91] They have also reported that knowledge of their pregnancy has often intensified violent and controlling behaviors on part of their boyfriends. Girls under age 18 are twice as likely to be beaten by their child's father than women over age 18. A UK study found that 70% of women who gave birth in their teens had experienced adolescent domestic violence. Similar results have been found in studies in the US. A Washington State study found 70% of teenage mothers had been beaten by their boyfriends, 51% had experienced attempts of birth control sabotage within the last year, and 21% experienced school or work sabotage.

In a study of 379 pregnant or parenting teens and 95 teenage girls without children, 62% of girls aged 11–15 and 56% of girls aged 16–19 reported experiencing domestic violence at the hands of their partners. Moreover, 51% of the girls reported experiencing at least one instance where their boyfriend attempted to sabotage their efforts to use birth control.[92]

Socioeconomic factors

Teenage pregnancy has been defined predominantly within the research field and among social agencies as a social problem. Poverty is associated with increased rates of teenage pregnancy.[74] Economically poor countries such as Niger and Bangladesh have far more teenage mothers compared with economically rich countries such as Switzerland and Japan.[93]

In the UK, around half of all pregnancies to under 18 are concentrated among the 30% most deprived population, with only 14% occurring among the 30% least deprived.[94] For example, in Italy, the teenage birth rate in the well-off central regions is only 3.3 per 1,000, while in the poorer Mezzogiorno it is 10.0 per 1,000.[60] Similarly, in the US, sociologist Mike A. Males noted that teenage birth rates closely mapped poverty rates in California:[95]

| County | Poverty rate | Birth rate* |

|---|---|---|

| Marin County | 5% | 5 |

| Tulare County (Caucasians) | 18% | 50 |

| Tulare County (Hispanics) | 40% | 100 |

* per 1,000 women aged 15–19

Teen pregnancy cost the US over $9.1 billion in 2004, including $1.9 billion for health care, $2.3 billion for child welfare, $2.1 billion for incarceration, and $2.9 billion in lower tax revenue.[96]

There is little evidence to support the common belief that teenage mothers become pregnant to get benefits, welfare, and council housing. Most knew little about housing or financial aid before they got pregnant and what they thought they knew often turned out to be wrong.[62]

Childhood environment

Girls exposed to abuse, domestic violence, and family strife in childhood are more likely to become pregnant as teenagers, and the risk of becoming pregnant as a teenager increases with the number of adverse childhood experiences.[97] According to a 2004 study, one-third of teenage pregnancies could be prevented by eliminating exposure to abuse, violence, and family strife. The researchers note that "family dysfunction has enduring and unfavorable health consequences for women during the adolescent years, the childbearing years, and beyond." When the family environment does not include adverse childhood experiences, becoming pregnant as an adolescent does not appear to raise the likelihood of long-term, negative psychosocial consequences.[98] Studies have also found that boys raised in homes with a battered mother, or who experienced physical violence directly, were significantly more likely to impregnate a girl.[99]

Studies have also found that girls whose fathers left the family early in their lives had the highest rates of early sexual activity and adolescent pregnancy. Girls whose fathers left them at a later age had a lower rate of early sexual activity, and the lowest rates are found in girls whose fathers were present throughout their childhood. Even when the researchers took into account other factors that could have contributed to early sexual activity and pregnancy, such as behavioral problems and life adversity, early father-absent girls were still about five times more likely in the US and three times more likely in New Zealand to become pregnant as adolescents than were father-present girls.[100][101]

Low educational expectations have been pinpointed as a risk factor.[102] A girl is also more likely to become a teenage parent if her mother or older sister gave birth in her teens.[39][66] A majority of respondents in a 1988 Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies survey attributed the occurrence of adolescent pregnancy to a breakdown of communication between parents and child and also to inadequate parental supervision.[71]

Foster care youth are more likely than their peers to become pregnant as teenagers. The National Casey Alumni Study, which surveyed foster care alumni from 23 communities across the US, found the birth rate for girls in foster care was more than double the rate of their peers outside the foster care system. A University of Chicago study of youth transitioning out of foster care in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin found that nearly half of the females had been pregnant by age 19. The Utah Department of Human Services found that girls who had left the foster care system between 1999 and 2004 had a birth rate nearly three times the rate for girls in the general population.[103]

Media influence

A study conducted in 2006 found that, adolescents who were more exposed to sexuality in the media were also more likely to engage in sexual activity themselves.[104] According to Time, "teens exposed to the most sexual content on TV are twice as likely as teens watching less of this material to become pregnant before they reach age 20".[105]

Prevention

Comprehensive sex education and access to birth control appear to reduce unplanned teenage pregnancy.[106] It is unclear which type of intervention is most effective.[106]

In the US free access to a long acting form of reversible birth control along with education decreased the rates of teen pregnancies by around 80% and the rate of abortions by more than 75%.[107] Currently there are four federal programs aimed at preventing teenage pregnancy: Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP), Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP), Title V Sexual Risk Avoidance Education, and Sexual Risk Avoidance Education.[108]

Education

The Dutch approach to preventing teenage pregnancy has often been seen as a model by other countries. The curriculum focuses on values, attitudes, communication and negotiation skills, as well as biological aspects of reproduction. The media has encouraged open dialogue and the health-care system guarantees confidentiality and a non-judgmental approach.[109]

In the United States, only 39 states and the District of Columbia out of the 50 states require some form of sex education of HIV education.[110] Out of these 39 states and the District of Columbia, only 17 states require that the sexual education provided be medically accurate, and only 3 states prohibit a program from promoting sexual education in a religious way. These three states include California, Colorado, and Louisiana. Additionally, 19 of those 39 states stress the importance of only having sex when in a committed marriage.[110] From this data, 11 states currently have no requirement for sexual education for any years of schooling, meaning these 11 states may have no sexual education at all. This could also mean these states are allowed to teach sexual education in any way they would like, including in medically inaccurate ways. This point is also valid for those 22 states that do not require sexual education to be medically accurate. Comprehensive sexual education has been proven to work to reduce the risk of teen pregnancies.[111] Without a nationwide mandate for medically accurate programs, teenagers in the United States are at risk for missing out on valuable information that can protect them. It is unfair to expect teenagers to make educated decisions about sex that can lead to teen pregnancy when they have never been properly educated about the issue. A program developed by experts in public health and sexual education titled National Sexuality Education Standards, is a valuable resource that describes what the minimum requirements of sexual education should be across the nation.[111] Giving teenagers the tools that are outlined in that roadmap would have positive effects, as it gives teenagers the resources to make educated decisions. Currently, there is not a national implementation of this program in the United States.

Teen pregnancy can be reduced by sex education as a study in 55 US counties (out of 2,927 counties) showed. The study used federal funded sex education programs as a proxy for sex education, but provided no details about funding levels, the number of students reached, or the amount of time spent on sex education. Nevertheless, the reduction of teenage births (not pregnancy) was significant, at 3% reduction, indicating that an increase in funding, education, or reach could increase teenage pregnancy even further.[112] Although 3% sounds like a small number, given a teenage girl population of 10 million females aged 15–19 (in 2020),[113] and ~190,000 teenage births per year, a 3% reduction would translate to about 6000 prevented teenage births per year when extrapolated to the whole nation.

Abstinence only education

Some schools provide abstinence-only sex education. Evidence does not support the effectiveness of abstinence-only sex education.[114] It has been found to be ineffective in decreasing HIV risk in the developed world,[115] and does not decrease rates of unplanned pregnancy when compared to comprehensive sex education.[114] It does not decrease the sexual activity rates of students, when compared to students who undertake comprehensive sexual education classes.[116]

Assistance

Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) is a non-profit organization operating in the United States and the UK designed to serve the needs of young mothers who may have special needs in their first pregnancy. Each mother served is partnered with a registered nurse early in her pregnancy and receives ongoing nurse home visits that continue through her child's second birthday. NFP intervention has been associated with improvements in maternal health, child health, and economic security.[117]

Canada

In 2018, Québec's Institut national de santé publique (INSPQ) began implementing adjustments to the Protocole de contraception du Québec (Québec Contraception Protocol). The new protocol allows registered nurses to prescribe hormonal birth control, an IUD or emergency birth control to women, as long as they comply with prescribed standards in the Prescription infirmière : Guide explicatif conjoint, and are properly trained in providing contraceptives. In 2020, Québec will offer online training to registered nurses, provided by the Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec (OIIQ). Nurses that do not have training in the areas of sexually transmitted and blood borne infections may have to take additional online courses provided by the INSPQ.[118]

United States

In the US, one policy initiative that has been used to increase rates of contraceptive use is Title X. Title X of the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970 (Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 91–572) provides family planning services for those who do not qualify for Medicaid by distributing "funding to a network of public, private, and nonprofit entities [to provide] services on a sliding scale based on income."[119] Studies indicate that, internationally, success in reducing teen pregnancy rates is directly correlated with the kind of access that Title X provides: "What appears crucial to success is that adolescents know where they can go to obtain information and services, can get there easily and are assured of receiving confidential, nonjudgmental care, and that these services and contraceptive supplies are free or cost very little."[82] In addressing high rates of unplanned teen pregnancies, scholars agree that the problem must be confronted from both the biological and cultural contexts.

On 30 September 2010, the US Department of Health and Human Services approved $155 million in new funding for comprehensive sex education programs designed to prevent teenage pregnancy. The money is being awarded "to states, non-profit organizations, school districts, universities and others. These grants will support the replication of teen pregnancy prevention programs that have been shown to be effective through rigorous research as well as the testing of new, innovative approaches to combating teen pregnancy."[120] Of the total of $150 million, $55 million is funded by Affordable Care Act through the Personal Responsibility Education Program, which requires states receiving funding to incorporate lessons about both abstinence and contraception.

Developing countries

In the developing world, programs of reproductive health aimed at teenagers are often small scale and not centrally coordinated, although some countries such as Sri Lanka have a systematic policy framework for teaching about sex within schools.[57] Non-governmental agencies such as the International Planned Parenthood Federation and Marie Stopes International provide contraceptive advice for young women worldwide. Laws against child marriage have reduced but not eliminated the practice. Improved female literacy and educational prospects have led to an increase in the age at first birth in areas such as Iran, Indonesia, and the Indian state of Kerala.

Other

A team of researchers and educators in California have published a list of "best practices" in the prevention of teen pregnancy, which includes, in addition to the previously mentioned concepts, working to "instill a belief in a successful future", male involvement in the prevention process, and designing interventions that are culturally relevant.[121]

Prevalence

In reporting teenage pregnancy rates, the number of pregnancies per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19 when the pregnancy ends is generally used.[123]

Worldwide, teenage pregnancy rates range from 143 per 1,000 in some sub-Saharan African countries to 2.9 per 1,000 in South Korea.[60][124] In the US, 82% of pregnancies in those between 15 and 19 are unplanned.[125] Among OECD developed countries, the US, the UK and New Zealand have the highest level of teenage pregnancy, while Japan and South Korea have the lowest in 2001.[126] According to the UNFPA, "In every region of the world – including high-income countries – girls who are poor, poorly educated or living in rural areas are at greater risk of becoming pregnant than those who are wealthier, well-educated or urban. This is true on a global level, as well: 95 percent of the world's births to adolescents (aged 15–19) take place in developing countries. Every year, some 3 million girls in this age bracket resort to unsafe abortions, risking their lives and health."[23]

According to a 2001 UNICEF survey, in 10 out of 12 developed nations with available data, more than two thirds of young people have had sexual intercourse while still in their teens. In Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Norway, the UK and the US, the proportion is over 80%. In Australia, the UK and the US, approximately 25% of 15-year-olds and 50% of 17-year-olds have had sex.[60] According to the Encyclopedia of Women's Health, published in 2004, approximately 15 million girls under the age of 20 in the world have a child each year. Estimates were that 20–60% of these pregnancies in developing countries are mistimed or unwanted.[84] As of 2022 it was reported by UNICEF that from 2000 to 2022, "the global adolescent birth rate for the age group 10–14 has declined by over 50 percent, from 3.3 to 1.6 per 1,000 adolescent girls aged 10–14", and "for the age group 15–19 has declined by over 30 percent, from 65 to 43 births per 1,000 adolescent girls aged 15–19".[15] UNICEF noted that these declines were "tied to improvements in almost all regional rates".[15]

Save the Children found that, annually, 13 million children are born to women aged under 20 worldwide, more than 90% in developing countries. Complications of pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of mortality among women aged 15–19 in such areas.[8]

Sub-Saharan Africa

The highest rate of teenage pregnancy in the world is in sub-Saharan Africa, where women tend to marry at an early age.[124] In Niger, for example, 87% of women surveyed were married and 53% had given birth to a child before the age of 18.[49] A recent study found that socio-cultural factors, economic factors, environmental factors, individual factors, and health service-related factors were responsible for the high rates of teenage pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa.[127]

India

In the Indian subcontinent, early marriage sometimes results in adolescent pregnancy, particularly in rural regions where the rate is much higher than it is in urbanized areas. Latest data suggests that teen pregnancy in India is high with 62 pregnant teens out of every 1,000 women.[128] India is fast approaching to be the most populous country in the world by 2050 and increasing teenage pregnancy, an important factor for the population rise, is likely to aggravate the problems.[129]

Asia

The rates of early marriage and pregnancy in some Asian countries are high. In recent years, the rates have decreased sharply in Indonesia and Malaysia,[130] although it remains relatively high in the former. However, in the industrialized Asian nations such as South Korea and Singapore, teenage birth rates remain among the lowest in the world.[57]

Australia

In 2015, the birth rate among teenage women in Australia was 11.9 births per 1,000 women.[131] The rate has fallen from 55.5 births per 1,000 women in 1971, probably due to ease of access to effective birth control, rather than any decrease in sexual activity.[132]

Europe

The overall trend in Europe since 1970 has been a decreasing total fertility rate, an increase in the age at which women experience their first birth, and a decrease in the number of births among teenagers.[133] Most continental Western European countries have very low teenage birth rates. This is varyingly attributed to good sex education and high levels of contraceptive use (in the case of the Netherlands and Scandinavia), traditional values and social stigmatization (in the case of Spain and Italy) or both (in the case of Switzerland).[12]

On the other hand, the teen birth rate is very high in Bulgaria and Romania. As of 2015, Bulgaria had a birth rate of 37/1.000 women aged 15–19, and Romania of 34.[134] The teen birth rate of these two countries is even higher than that of underdeveloped countries like Burundi and Rwanda.[134] Many of the teen births occur in Roma populations, who have an occurrence of teenage pregnancies well above the local average.[135]

United Kingdom

The teen pregnancy rate in England and Wales was 23.3 per 1,000 women aged 15 to 17. There were 5,740 pregnancies in girls aged under 18 in the three months to June 2014, data from the Office for National Statistics shows. This compares with 6,279 in the same period in 2013 and 7,083 for the June quarter the year before that. Historically, the UK has had one of the highest teenage pregnancy and abortion rates in Western Europe.

There are no comparable rates for conceptions across Europe, but the under-18 birth rate suggests England is closing the gap. The under-18 birth rate in 2012 in England and Wales was 9.2, compared with an EU average of 6.9. However, the UK birth rate has fallen by almost a third (32.3%) since 2004 compared with a fall of 15.6% in the EU. In 2004, the UK rate was 13.6 births per 1,000 women aged 15–17 compared with an EU average rate of 7.7.

United States

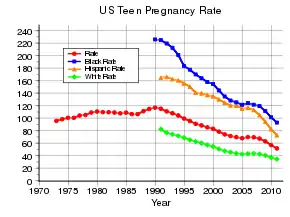

In 2001, the teenage birth rate in the US was the highest in the developed world, and the teenage abortion rate is also high.[60] In 2005 in the US, the majority (57%) of teen pregnancies resulted in a live birth, 27% ended in an induced abortion, and 16% in a fetal loss.[137] The US teenage pregnancy rate was at a high in the 1950s and has decreased since then, although there has been an increase in births out of wedlock.[138] The teenage pregnancy rate decreased significantly in the 1990s; this decline manifested across all racial groups, although teenagers of African-American and Hispanic descent retain a higher rate, in comparison to that of European-Americans and Asian-Americans. The Guttmacher Institute attributed about 25% of the decline to abstinence and 75% to the effective use of contraceptives.[139] While in 2006 the US teen birth rate rose for the first time in fourteen years,[140] it reached a historic low in 2010: 34.3 births per 1,000 women aged 15–19.[1] As of 2017, the birth rate for teen pregnancy from girls ages 15–19 was at 18.8 per 1,000 women between this age group.[141] Given a teenage girl population of 10 million females (aged 15–19, in 2020),[113] this would translate to ~190,000 births per year.

The Latina teenage pregnancy rate is 75% higher pregnancy rate than the national average.[44]

The latest data from the US shows that the states with the highest teenage birthrate are Mississippi, New Mexico and Arkansas while the states with the lowest teenage birthrate are New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Vermont.[142]

Canada

The Canadian teenage birth trended towards a steady decline for both younger (15–17) and older (18–19) teens in the period between 1992 and 2002;[143] it further dropped by a factor of more than 2-fold between 2000 and 2020 (from 20.1 per 1000 women in 2000 to 8.4 in 2020).[144] Still, in Canada, the stability of familial structure significantly influences the risk of teenage pregnancy. Experiencing one or more episodes of poverty before the age of 13 made young Canadian girls 75% to 90% more vulnerable to teenage pregnancy.[145]

Teenage fatherhood

In some cases, the father of the child is the husband of the teenage girl. The conception may occur within wedlock, or the pregnancy itself may precipitate the marriage (the so-called shotgun wedding). In countries such as India, the majority of teenage births occur within marriage.[57][60]

In other countries, such as the US and Ireland, the majority of teenage mothers are not married to the father of their children.[60][146] In the UK, half of all teenagers with children are lone parents, 40% are cohabitating as a couple and 10% are married.[147] Teenage parents are frequently in a romantic relationship at the time of birth, but many adolescent fathers do not stay with the mother and this often disrupts their relationship with the child. US surveys tend to under-report the prevalence of teen fatherhood.[148] In many cases, "teenage father" may be a misnomer. Studies by the Population Reference Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics found that about two-thirds of births to teenage girls in the US are fathered by adult men aged over 20.[149][150] The Guttmacher Institute reports that over 40% of mothers aged 15–17 had sexual partners three to five years older and almost one in five had partners six or more years older.[151] A 1990 study of births to California teens reported that the younger the mother, the greater the age gap with her male partner.[152] In the UK, 72% of jointly registered births to women aged under 20, the father is over 20, with almost 1 in 4 being over 25.[153]

Intersection of society and culture

Teenage pregnancy remains a significant social and cultural issue in many countries around the world. While the rate of teenage pregnancies has declined in recent decades, it continues to be a cause for concern, both from a health perspective and in terms of its impact on the lives of young people.[154]

The causes of teenage pregnancy are complex and multi-faceted, reflecting the interplay between individual behavior, societal norms and cultural attitudes.[155] In many cultures, there is a lack of comprehensive sexual education, which contributes to a lack of understanding about contraception and sexually transmitted infections.[156] There is also a cultural stigma attached to discussing sexual health and relationships, which makes it difficult for young people to access the information and support they need.[157]

In addition, poverty, lack of access to healthcare, and limited opportunities for education and employment can also contribute to the high rate of teenage pregnancy.[158] These factors can make it difficult for young people to make informed choices about their sexual health and can limit their ability to access contraception and other forms of protection.[159]

The effects of teenage pregnancy can be far-reaching and long-lasting. Pregnant teenagers are at increased risk of health problems, including complications during pregnancy and childbirth, and are more likely to experience poverty and limited opportunities later in life.[154] Their children are also more likely to experience health and developmental problems, and to grow up in poverty.[160]

Despite these challenges, there are many programs and initiatives aimed at reducing the rate of teenage pregnancy and supporting young people who become pregnant. These efforts include comprehensive sex education programs, access to contraception and family planning services, and support for young mothers.[156]

In conclusion, teenage pregnancy is a complex issue that reflects the interplay between individual behavior, societal norms and cultural attitudes. Addressing this issue requires a comprehensive approach that includes education, access to healthcare, and support for young people.[161] By working together, we can help to reduce the rate of teenage pregnancy and improve the lives of young people and their families.[162]

Politics

Some politicians condemn pregnancy in unmarried teenagers as a drain on taxpayers, if the mothers and children receive welfare payments and social housing from the government.[163][164]

Media

Terry Tate, a former teacher and graduate from Seton Hall University used his knowledge of issues concerning young students at his school which included teenage pregnancy to compose the song, "Babies Having Babies".[165] Radio stations became involved in trying to get the message across.[166] It ended up being a national hit on the Billboard[167][168] and Cash Box charts in 1989.[169][170]

See also

References

- Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J. (10 April 2012). "Birth Rates for U.S. Teenagers Reach Historic Lows for All Age and Ethnic Groups". NCHS Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (89): 1–8. PMID 22617115. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- Adolescent Pregnancy (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. p. 5. ISBN 978-9241591454. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "Adolescent pregnancy". World Health Organization. 23 February 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Oringanje, Chioma; Meremikwu, Martin M; Eko, Hokehe; Esu, Ekpereonne; Meremikwu, Anne; Ehiri, John E (3 February 2016). "Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (2): CD005215. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005215.pub3. PMC 8730506. PMID 26839116.

- "Adolescent health". World Health Organization. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- Hirsch, Larissa (September 2016). "Can a Girl Get Pregnant if She Has Never Had Her Period?".

- Mishra, Gita D.; Cooper, Rachel; Tom, Sarah E.; Kuh, Diana (2009). "Early Life Circumstances and Their Impact on Menarche and Menopause". Medscape.

- Mayor S (2004). "Pregnancy and childbirth are leading causes of death in teenage girls in developing countries". BMJ. 328 (7449): 1152. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1152-a. PMC 411126. PMID 15142897.

- Makinson C (1985). "The health consequences of teenage fertility". Family Planning Perspectives. 17 (3): 132–139. doi:10.2307/2135024. JSTOR 2135024. PMID 2431924.

- Loto OM, Ezechi OC, Kalu BK, Loto A, Ezechi L, Ogunniyi SO (2004). "Poor obstetric performance of teenagers: Is it age- or quality of care-related?". Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 24 (4): 395–398. doi:10.1080/01443610410001685529. PMID 15203579. S2CID 43808921.

- Raatikainen, Kaisa; Heiskanen, Nonna; Verkasalo, Pia K.; Heinonen, Seppo (1 April 2006). "Good outcome of teenage pregnancies in high-quality maternity care". European Journal of Public Health. 16 (2): 157–161. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cki158. ISSN 1464-360X. PMID 16141302.

- "Young mothers face stigma and abuse, say charities". BBC News. 25 February 2014.

- International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. 2018. p. 18. ISBN 978-92-3-100259-5.

- "Adolescent pregnancy". www.who.int. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- "Early childbearing can have severe consequences for adolescent girls". UNICEF. December 2022.

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2022. Summary of Results (PDF). New York.

- Kost, K., Maddow-Zimet, I., & Arpaia, A. (2017). Pregnancies, births, and abortions among adolescents and young women in the United States, 2013: National and state trends by age, race and ethnicity. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute. Lay summary at ChildTrends.org Archived 11 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Kost K, Henshaw S, Carlin L (2010). "U.S. Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions: National and State Trends and Trends by Race and Ethnicity" (PDF).

Pregnancies are the sum of births, abortions and miscarriages. Please note that in these tables, "age" refers to the woman's age when the pregnancy ended. Consequently, actual numbers of pregnancies that occurred among teenagers are higher than those reported here, because most of the women who conceived at age 19 had their births or abortions after they turned 20 and, thus, were not counted as teenagers.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Mosher, William D.; Jones, Jo; Abma, Joyce C. (24 July 2012). "Intended and unintended births in the United States: 1982-2010". National Health Statistics Reports (55): 1–28. ISSN 2164-8344. PMID 23115878.

- Lappegård, Trude (15 March 2000). "New fertility trends in Norway". Demographic Research. 2. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2000.2.3. JSTOR 26348001.

- Alex Hern (23 June 2015). "Is broadband responsible for falling teenage pregnancy rates?". The Guardian.

- "PRESIDENT WILLIAM JEFFERSON CLINTON STATE OF THE UNION ADDRESS". clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov.

- "Adolescent Pregnancy". UNFPA. 2013.

- "Adolescent pregnancy - UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund".

- "Adolescent pregnancy". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- Stepp, G. (2009) Teen Pregnancy: The Tangled Web. vision.org

- "Few teens use the most effective types of birth control| CDC Online Newsroom | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "American Teens' Sexual and Reproductive Health". Guttmacher Institute. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. (2002). "Not Just Another Single Issue: Teen Pregnancy Prevention's Link to Other Critical Social Issues" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. (147 KB). Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- Hofferth SL, Reid L, Mott FL (2001). "The effects of early childbearing on schooling over time". Family Planning Perspectives. 33 (6): 259–267. doi:10.2307/3030193. JSTOR 3030193. PMID 11804435.

- "The Psychological Effects of Teenage Women During Pregnancy". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- "Statistics on Teen Pregnancy". National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy

- Cornelius MD, Goldschmidt L, Willford JA, Leech SL, Larkby C, Day NL (2008). "Body Size and Intelligence in 6-year-olds: Are Offspring of Teenage Mothers at Risk?". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 13 (6): 847–856. doi:10.1007/s10995-008-0399-0. PMC 2759844. PMID 18683038.

- Kalmuss DS, Namerow PB (1994). "Subsequent childbearing among teenage mothers: the determinants of a closely spaced second birth". Fam Plann Perspect. 26 (4): 149–53, 159. doi:10.2307/2136238. JSTOR 2136238. PMID 7957815.

- Gibbs, CM.; Wendt, A.; Peters, S.; Hogue, CJ. (Jul 2012). "The impact of early age at first childbirth on maternal and infant health". Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 26 Suppl 1 (1): 259–84. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01290.x. PMC 4562289. PMID 22742615.

- American Academy Of Pediatrics. Committee On Adolescence Committee On Early Childhood Adoption, Dependent Care (2001). "American Academy of Pediatrics: Care of adolescent parents and their children". Pediatrics. 107 (2): 429–34. doi:10.1542/peds.107.2.429. PMID 11158485. S2CID 71188516.

- Hofferth SL, Reid L (2002). "Early Childbearing and Children's Achievement And Behavior over Time". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 34 (1): 41–49. doi:10.2307/3030231. JSTOR 3030231. PMID 11990638. S2CID 13558045.

- Crockenberg S (1987). "Predictors and correlates of anger toward and punitive control of toddlers by adolescent mothers". Child Dev. 58 (4): 964–75. doi:10.2307/1130537. JSTOR 1130537. PMID 3608666.

- Furstenberg FF, Levine JA, Brooks-Gunn J (1990). "The children of teenage mothers: patterns of early childbearing in two generations". Fam Plann Perspect. 22 (2): 54–61. doi:10.2307/2135509. JSTOR 2135509. PMID 2347409.

- Maynard, Rebecca A. (Ed.). (1996).Kids Having Kids Archived 26 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Belsky DH (1994). "Prenatal care and maternal health during adolescent pregnancy: A review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Adolescent Health. 15 (6): 444–456. doi:10.1016/1054-139X(94)90491-K. PMID 7811676.

- Banerjee B, Pandey G, Dutt D, Sengupta B, Mondal M, Deb S (2009). "Teenage pregnancy: A socially inflicted health hazard". Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 34 (3): 227–231. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.55289. PMC 2800903. PMID 20049301.

- Guttmacher Institute. (September 1999).Teen Sex and Pregnancy Archived 3 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 29 May 2006.

- Sterling, Sandra P. (2009). "Contraceptive Use Among Adolescent Latinas Living in the United States: The Impact of Culture and Acculturation". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 23 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2008.02.004. PMID 19103403.

- Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Verkasalo PK, Heinonen S (2005). "Good outcome of teenage pregnancies in high-quality maternity care". The European Journal of Public Health. 16 (2): 157–161. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cki158. PMID 16141302.

- Gutierrez Y, King JC (1993). "Nutrition during teenage pregnancy". Pediatric Annals. 22 (2): 99–108. doi:10.3928/0090-4481-19930201-07. PMID 8493060.

- Sanchez PA, Idrisa A, Bobzom DN, Airede A, Hollis BW, Liston DE, Jones DD, Dasgupta A, Glew RH (1997). "Calcium and vitamin D status of pregnant teenagers in Maiduguri, Nigeria". Journal of the National Medical Association. 89 (12): 805–811. PMC 2608295. PMID 9433060.

- Peña E, Sánchez A, Solano L (2003). "Profile of nutritional risk in pregnant adolescents". Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutricion. 53 (2): 141–149. PMID 14528603.

- Locoh, Thérèse (1999). "Early Marriage and Motherhood in Sub-Saharan Africa". African Environment. 10 (3): 31–42. S2CID 70677057.

- United Nations Population Fund (2014). "Population and poverty". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (2016). "Negative Impacts of Teen Childbearing". Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- O’Halloran, Peggy (April 1998) Pregnancy, Poverty, School and Employment. moappp.org. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL (1998). "Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood. Recent evidence and future directions". The American Psychologist. 53 (2): 152–166. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.152. PMID 9491745.

- Social Exclusion Unit. (1999). Teenage Pregnancy. Retrieved 29 May 2006.

- Teenage pregnancy. everychildmatters.gov.uk

- Mehta, Suman; Groenen, Riet; Roque, Francisco (1998). "Adolescents in Changing Times: Issues and Perspectives for Adolescent Reproductive Health in The ESCAP Region". United Nations Social and Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - MacLeod, C. (1999). "The 'Causes' of Teenage Pregnancy: Review of South African Research – Part 2". South African Journal of Psychology. 29: 8–16. doi:10.1177/008124639902900102. S2CID 144455158.

- Fog, A. (28 February 1999). Cultural Selection. Springer. ISBN 9780792355793.

- UNICEF. (2001)."A League Table of Teenage Births in Rich Nations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2006. (888 KB). Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Beginning Too Soon: Adolescent Sexual Behavior, Pregnancy And Parenthood, US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 25 January 2007.

- Teenage Mothers : Decisions and Outcomes – Provides a unique review of how teenage mothers think Archived 24 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine Policy Studies Institute, University of Westminster, 30 October 1998

- Guttmacher Institute. (2005). Sex and Relationships. Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- Avci, Ilknur Aydin; Cavusoglu, Figen; Aydin, Mesiya; Altay, Birsen (17 January 2018). "Attitude and practice of family planning methods among Roma women living in northern Turkey". International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 5 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.01.002. PMC 6626220. PMID 31406798.

- East PL (1996). "Do adolescent pregnancy and childbearing affect younger siblings?". Family Planning Perspectives. 28 (4): 148–153. doi:10.2307/2136190. JSTOR 2136190. PMID 8853279.

- East PL, Jacobson LJ (2001). "The younger siblings of teenage mothers: a follow-up of their pregnancy risk". Dev Psychol. 37 (2): 254–64. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.254. PMC 3878983. PMID 11269393.

- East, P. L. (1998). "Impact of Adolescent Childbearing on Families and Younger Sibling: Effects that Increase Younger Siblings' Risk for Early Pregnancy". Applied Developmental Science. 2 (2): 62–74. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0202_1.

- "Teenage pregnancy is 'contagious'". BBC News. 9 August 2011.

- Guttmacher Institute (2003) In Their Own Right: Addressing the Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs of Men Worldwide. Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine pp. 19–21.

- "U.S.Teen Sexual Activity" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2008. (147 KB) Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2005. Retrieved 23 January 2007

- The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. (1997). What the Polling Data Tell Us: A Summary of Past Surveys on Teen Pregnancy. teenpregnancy.org (April 1997).

- Allen, Colin. (22 May 2003). "Peer Pressure and Teen Sex." Psychology Today. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- Theuri, Joseph and Nzioka, David (2021). Alcohol and drug abuse as ecological predictors of risk taking behaviour among secondary school students in Kajiado North Sub-County, Kajiado County, Kenya. African Journal of Empirical Research, 2 (1), 50-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.51867/ajer.v2i1.9

- Besharov, D. J.; Gardiner, K. N. (1997). "Trends in Teen Sexual Behavior". Children and Youth Services Review. 19 (5–6): 341–367. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.673.5213. doi:10.1016/S0190-7409(97)00022-4. PMID 12295352.

- Sax, Leonard (2005) Why Gender Matters. Doubleday books, p. 128, ISBN 0786176814

- Deardorff, J; Gonzales, NA; Christopher, FS; Roosa, MW; Millsap, RE (2005). "Early puberty and adolescent pregnancy: the influence of alcohol use". Pediatrics. 116 (6): 1451–6. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.558.9628. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0542. PMID 16322170. S2CID 36296702.

- Slater, Jon. (2000). "Britain: Sex Education Under Fire." The UNESCO Courier Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Adams, A.; D'Souza, R. (2009). "Teenage contraception". General Practice Update. 2 (6): 36–39.

- National Surveys of Family GrowthTrussell J, Wynn LL (January 2008). "Reducing unintended pregnancy in the United States". Contraception. 77 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.001. PMID 18082659. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- Speidel, J. J.; Harper, C. C.; Shields, W. C. (2008). "The potential of long-acting reversible contraception to decrease unintended pregnancy". Contraception. 78 (3): 197–200. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.06.001. PMID 18692608.

- Biggs, M. A.; Karasek, D; Foster, D. G. (2012). "Unprotected intercourse among women wanting to avoid pregnancy: Attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs". Women's Health Issues. 22 (3): e311–8. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2012.03.003. PMID 22555219.

- Darroch, Jacqueline E.; Jennifer J. Frost; Susheela Singh. "Teenage Sexual and Reproductive Behavior in Developed Countries: Can More Progress Be Made?" (PDF). The Alan Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- "Teenage pregnancy myth dismissed". BBC News. 22 January 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Teen Pregnancy" (2004) in Encyclopedia of Women's Health.

- Speizer, I. S.; Pettifor, A; Cummings, S; MacPhail, C; Kleinschmidt, I; Rees, H. V. (2009). "Sexual violence and reproductive health outcomes among South African female youths: A contextual analysis". American Journal of Public Health. 99 (Suppl 2): S425–31. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.136606. PMC 3515795. PMID 19372525.

- Cullinan, Kerry Teen mothers often forced into sex. www.csa.za.org. 23 November 2003

- Saewyc EM, Magee LL, Pettingell SE (2004). "Teenage pregnancy and associated risk behaviors among sexually abused adolescents". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 36 (3): 98–105. doi:10.1363/3609804. PMID 15306268.

- Saewyc, E. M.; Magee, L. L.; Pettingell, S. E. (2004). "Teenage pregnancy and associated risk behaviors among sexually abused adolescents". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 36 (3): 98–105. doi:10.1363/3609804. PMID 15306268.

- Study Links Childhood Sexual Abuse, Teen Pregnancy Archived 29 June 2012 at archive.today University of Southern California, Science Blog, 2004

- Rosen D (2004). ""I Just Let Him Have His Way" Partner Violence in the Lives of Low-Income, Teenage Mothers". Violence Against Women. 10 (1): 6–28. doi:10.1177/1077801203256069. S2CID 72957028.

- Quinlivan J (Winter 2006). "Teenage pregnancy" (PDF). O&G. 8 (2): 25–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- Violence, Abuse and Adolescent Childbearing Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Florida State University Center for Prevention & Early Intervention Policy (2005)

- Indicator: Births per 1000 women (aged 15–19) – 2002 UNFPA, State of World Population 2003. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- "Teenage Conceptions By Small Area Deprivation In England and Wales 2001-2" (Spring 2007)Health Statistics Quarterly Volume 33

- Males, Mike (2001) America’s Pointless "Teen Sex" Squabble Archived 13 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, c Youth Today.

- Teen Births Cost U.S. Government $9.1B In 2004 Despite Drop In Teen Birth, Pregnancy Rates, Report Says Archived 12 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Medical News Today. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Smith, Carolyn (1996). "The link between childhood maltreatment and teenage pregnancy". Social Work Research. 20 (3): 131–141. doi:10.1093/swr/20.3.131.

- Tamkins, T. (2004) Teenage pregnancy risk rises with childhood exposure to family strife Archived 4 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, March–April 2004

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Croft JB, Williamson DF, Santelli J, Dietz PM, Marks JS (2001). "Abused boys, battered mothers, and male involvement in teen pregnancy". Pediatrics. 107 (2): E19. doi:10.1542/peds.107.2.e19. PMID 11158493.

- Ellis BJ, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Pettit GS, Woodward L (2003). "Does father absence place daughters at special risk for early sexual activity and teenage pregnancy?". Child Development. 74 (3): 801–821. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00569. PMC 2764264. PMID 12795391.

- Quigley, Ann (2003) Father's Absence Increases Daughter's Risk of Teen Pregnancy Archived 6 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Health Behavior News Service, 27 May 2003

- Allen E, Bonell C, Strange V, Copas A, Stephenson J, Johnson AM, Oakley A (2007). "Does the UK government's teenage pregnancy strategy deal with the correct risk factors? Findings from a secondary analysis of data from a randomised trial of sex education and their implications for policy". J Epidemiol Community Health. 61 (1): 20–7. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.040865. PMC 2465587. PMID 17183010.

- "Fostering Hope: Preventing Teen Pregnancy Among Youth in Foster Care" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. (42.1 KB) A Joint Project of The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy and UCAN (Uhlich Children’s Advantage Network) 16 February 2006

- L'Engle, KL; Brown, JD; Kenneavy, K (2006). "The mass media are an important context for adolescents' sexual behavior". Journal of Adolescent Health. 38 (3): 186–192. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.020. PMID 16488814.

- Park, Alice (3 November 2008). "Sex on TV Increases Teen Pregnancy, Says Report". Time. Archived from the original on 6 November 2008.

- Oringanje, Chioma; Meremikwu, Martin M; Eko, Hokehe; Esu, Ekpereonne; Meremikwu, Anne; Ehiri, John E (3 February 2016). "Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (2): CD005215. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005215.pub3. PMC 8730506. PMID 26839116.

- Secura, Gina M.; Madden, Tessa; McNicholas, Colleen; Mullersman, Jennifer; Buckel, Christina M.; Zhao, Qiuhong; Peipert, Jeffrey F. (2 October 2014). "Provision of No-Cost, Long-Acting Contraception and Teenage Pregnancy". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (14): 1316–1323. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1400506. PMC 4230891. PMID 25271604.

- Fernandes-Alcantara, Adrienne L. (30 April 2018). Teen Pregnancy: Federal Prevention Programs (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Valk, Guus (July 2000). "The Dutch Model" (PDF). The UNESCO Courier. 53 (7): 19. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- "Sex and HIV Education". Guttmacher Institute. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "Sexuality Education". Advocates for Youth. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Mark, Nicholas D. E.; Wu, Lawrence L. (22 February 2022). "More comprehensive sex education reduced teen births: Quasi-experimental evidence". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (8): e2113144119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11913144M. doi:10.1073/pnas.2113144119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8872707. PMID 35165192.

- "U.S. population by age and gender 2019". Statista. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- Ott, Mary A; Santelli, John S (October 2007). "Abstinence and abstinence-only education". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 19 (5): 446–452. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282efdc0b. PMC 5913747. PMID 17885460.

- Underhill, K; Operario, D; Montgomery, P (17 October 2007). Operario, Don (ed.). "Abstinence-only programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005421. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005421.pub2. PMID 17943855.

- Kohler, Pamela; Lafferty, William; Manhart, Lisa (April 2008). "Abstinence-Only and Comprehensive Sex Education and the Initiation of Sexual Activity and Teen Pregnancy". Journal of Adolescent Health. 42 (4): 344–351. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026. PMID 18346659. S2CID 16986622.

- "Nurse-Family Partnership". Social Programs that Work. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec. 2018. Protocole de contraception du Québec Mise à jour 2018.

- The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. "Policy Brief: Title X Plays a Critical Role in Preventing Unplanned Pregnancy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. "HHS Awards Evidence-based Teen Pregnancy Prevention Grants". Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- Fe Moncloa; Marilyn Johns; Elizabeth J. Gong; Stephen Russell; Faye Lee; Estella West (2003). "Best Practices in Teen Pregnancy Prevention Practitioner Handbook". Journal of Extension. 41 (2). Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- "Adolescent birth rate in women aged 10-19 years". Our World in Data. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Teenage pregnancy –Definitions. Statcan.gc.ca (5 June 2007). Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- Treffers PE (2003). "Teenage pregnancy, a worldwide problem". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 147 (47): 2320–2325. PMID 14669537.

- Marnach ML, Long ME, Casey PM (2013). "Current Issues in Contraception". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88 (3): 295–299. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.01.007. PMID 23489454.

- A League Table of Teenage Births in Rich Nations. unicef-irc.org ISBN 88-85401-75-9

- Yakubu, Ibrahim; Salisu, Waliu Jawula (December 2018). "Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review". Reproductive Health. 15 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0460-4. PMC 5787272. PMID 29374479. S2CID 28017533.

- Dawan, Himanshi (28 November 2008). "Teen pregnancies higher in India than even UK, US". The Economic times. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- Kumar A, Singh T, Basu S, Pandey S, Bhargava V (2007). "Outcome of teenage pregnancy". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 74 (10): 927–931. doi:10.1007/s12098-007-0171-2. PMID 17978452. S2CID 37537112.

- Jones, Gavin (2010). Changing Marriage Patterns in Asia (Report). doi:10.2139/ssrn.1716533. S2CID 53398466. SSRN 1716533.

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (13 December 2017). "Media Release – September most common month for babies born in Australia (Media Release)".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Teenage pregnancy – Better Health Channel". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Teen pregnancy rate 'lower still'". BBC News. 25 February 2014.

- "Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1,000 women ages 15–19) – Data". data.worldbank.org.

- "Silence Makes Babies – Transitions Online". www.tol.org. 6 July 2010.

- Kost, Kathryn; Maddow-Zimet, Isaac (April 2016). "U.S. Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions, 2011: National Trends by Age, Race and Ethnicity". Guttmacher Institute.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011) Health Disparities and Inequality Report – United States, MMWR, Jan 14, 2011 volume 60" (PDF).

- Boonstra, Heather (February 2002). "The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy". 5 (1). Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - U.S. Teenage Pregnancy Rate Drops For 10th Straight Year." Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Mathews, T.J. (7 January 2009). "Births: Final Data for 2006" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. 57 (7).

- "About Teen Pregnancy | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- U.S. teen birth rates fall to historic lows. CBS News (10 April 2012). Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- Dryburgh, H. (2002). Teenage pregnancy. Health Reports, 12 (1), 9–18; Statistics Canada . (2005). Health Indicators, 2005, 2. Retrieved from Facts and Statistics: Sexual Health and Canadian Youth – Teen Pregnancy Rates Archived 30 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Adolescent fertility rates, 2000 to 2020 – the Health of Canada's Children and Youth".

- Smith, Chelsea; Strohschein, Lisa; Crosnoe, Robert (October 2018). "Family Histories and Teen Pregnancy in the United States and Canada". Journal of Marriage and Family. 80 (5): 1244–1258. doi:10.1111/jomf.12512. ISSN 0022-2445. PMC 6289283. PMID 30555182.

- National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. (2007). Do most teens who choose to raise the child get married when they find out they're pregnant?

- "Census 2001 People aged 16–29" Office For National Statistics

- Joyner, K; Peters, H.E.; Hynes, K; et al. (2012). "The Quality of Male Fertility Data in Major U.S. Surveys". Demography. 49 (1): 101–124. doi:10.1007/s13524-011-0073-9. PMC 3500148. PMID 22203451.

- De Vita; Carol J. (March 1996). "The United States at Mid-Decade". Population Bulletin. 50 (4). Archived from the original on 24 July 2008.

- National Center for Health Statistic (September 1993). "Advance Report of Final Natality Statistics, 1991" (PDF). Monthly Vital Statistics Report. 42 (3, Supplement 9).

- Family Planning Perspectives, July/August 1995.

- California Resident Live Births, 1990, by Age of Father, by Age of Mother, California Vital Statistics Section, Department of Health Services, 1992.

- FM1 Birth statistics no.34 (2005) Office For National Statistics pp. 14–15. Note: 24% of births to women under 20 were solo registrations where the age of the father cannot be determined.

- "Adolescent pregnancy". www.who.int. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- Akella, Devi; Jordan, Melissa (1 April 2015). "Impact of Social and Cultural Factors on Teenage Pregnancy". Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 8 (1). ISSN 2166-5222.

- "About Teen Pregnancy | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 15 November 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2023.