Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, KG, KP, GCB, GCH, PC (Edward Augustus; 2 November 1767 – 23 January 1820) was the fourth son and fifth child of King George III. His only child, Victoria, became Queen of the United Kingdom 17 years after his death.

| Prince Edward | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke of Kent and Strathearn | |||||

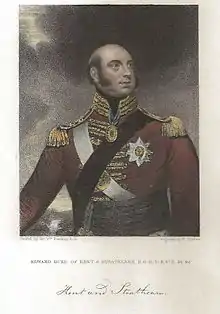

Portrait by Sir William Beechey, 1818 (originally owned by Mme de Saint-Laurent) | |||||

| Born | 2 November 1767 Buckingham House, London, England | ||||

| Died | 23 January 1820 (aged 52) Woolbrook Cottage, Sidmouth, England | ||||

| Burial | 12 February 1820[1] Royal Vault, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom | ||||

| |||||

| House | Hanover | ||||

| Father | George III of the United Kingdom | ||||

| Mother | Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz | ||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | |||||

| Years of active service | 1786–1805 | ||||

| Rank | Field marshal (active service) | ||||

| Unit | 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers) | ||||

| Commands held | |||||

| Battles/wars | |||||

| Awards | Mentioned in dispatches | ||||

Prince Edward was created Duke of Kent and Strathearn and Earl of Dublin on 23 April 1799[2] and, a few weeks later, appointed a General and commander-in-chief of British forces in the Maritime Provinces of North America.[3] On 23 March 1802, he was appointed Governor of Gibraltar and nominally retained that post until his death. The Duke was appointed Field-Marshal of the Forces on 3 September 1805.[4]

Edward was the first member of the royal family to live in North America for more than a short visit (1791–1800) and, in 1794, the first prince to enter the United States (travelling to Boston on foot from Lower Canada) after independence. He is credited with the first use, on 27 June 1792, of the term Canadian to mean both French and English settlers in Upper and Lower Canada. The Prince used the term in an effort to quell a riot between the two groups at a polling station in Charlesbourg, Lower Canada.[5] In the 21st century, he has been styled the "Father of the Canadian Crown" for his impact on the development of Canada.[6]

Early life

Prince Edward was born on 2 November 1767[7] to King George III and Queen Charlotte. He was fourth in the line of succession to the British throne. He was named after his uncle Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany, who had died several weeks earlier and was buried at Westminster Abbey the day before Edward's birth.

Edward was baptised on 30 November 1767; his godparents were the Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg (his paternal uncle by marriage, for whom the Earl of Hertford, Lord Chamberlain, stood proxy), Duke Charles of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (his maternal uncle, for whom the Earl of Huntingdon, Groom of the Stole, stood proxy), the Hereditary Princess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (his paternal aunt, who was represented by a proxy) and the Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel (his paternal grandfather's sister, for whom the Duchess of Argyll, Lady of the Bedchamber to the Queen, stood proxy).

Edward aged eleven (right) and his older brother William, portrait by Benjamin West, 1778

Edward aged eleven (right) and his older brother William, portrait by Benjamin West, 1778 Prince Edward in 1782, portrait by Thomas Gainsborough

Prince Edward in 1782, portrait by Thomas Gainsborough

Military career

Army

The Prince began his military training in the Electorate of Hanover in 1785. King George III intended to send him to the University of Göttingen, but decided against it upon the advice of the Duke of York. Instead, Edward went to Lüneburg and later Hanover, accompanied by his German tutor, Lieutenant Colonel George von Wangenheim, Baron Wangenheim.[8] On 30 May 1786, he was appointed a brevet colonel in the British Army.[9] From 1788 to 1789, he completed his education in Geneva.[7] On 5 August 1789, aged 22, he became a mason in L'Union, the most important Genevan masonic lodge in the 19th century.[10]

In 1789, he was appointed colonel of the 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers). In 1790, he returned home without leave and, in disgrace, was sent off to Gibraltar as an ordinary officer. He was joined from Marseilles by Madame de Saint-Laurent.[7]

Quebec

Due to the extreme Mediterranean heat, Edward requested to be transferred to present-day Canada, specifically Quebec, in 1791.[11] Edward arrived in Canada in time to witness the proclamation of the Constitutional Act of 1791, became the first member of the Royal Family to tour Upper Canada, and became a fixture of British North American society. Edward and his mistress, Julie St. Laurent, became close friends with the French Canadian family of Ignace-Michel-Louis-Antoine d'Irumberry de Salaberry; the Prince mentored all of the family's sons throughout their military careers. Edward guided Charles de Salaberry throughout his career, and made sure that the famous commander was duly honoured after his leadership during the Battle of Chateauguay.

The prince was promoted to the rank of major-general in October 1793.[12] He served successfully in the West Indies campaign the following year, and was commander of the British camp at La Coste during the Battle of Martinique, for which he was mentioned in dispatches by General Charles Grey for his "great Spirit and Activity".[13] He subsequently received the thanks of Parliament.

Nova Scotia

_-_Edward%252C_Duke_of_Kent_(1767-1820)_-_RCIN_401521_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

After 1794, Prince Edward lived at the headquarters of the Royal Navy's North American Station located in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He was instrumental in shaping that settlement's military defences, protecting its important Royal Navy base, as well as influencing the city's and colony's socio-political and economic institutions. Edward was responsible for the construction of Halifax's iconic Garrison Clock, as well as numerous other civic projects such as St. George's Round Church. Lieutenant Governor Sir John Wentworth and Lady Francis Wentworth provided their country residence for the use of Prince Edward and Julie St. Laurent. Extensively renovated, the estate became known as "Prince's Lodge" as the couple hosted numerous dignitaries, including Louis-Phillippe of Orléans (the future King of the French). All that remains of the residence is a small rotunda built by Edward for his regimental band to play music.

After suffering a fall from his horse in late 1798, he was allowed to return to England.[7] On 24 April 1799,[2] Prince Edward was created Duke of Kent and Strathearn and Earl of Dublin, and received the thanks of parliament and an income of £12,000 (£1.25 million in 2021).[14] In May that same year, the Duke was promoted to the rank of general and appointed Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America.[7] He took leave of his parents on 22 July 1799[15] and sailed to Halifax. Just over twelve months later he left Halifax[16] and arrived in England on 31 August 1800 where it was confidently expected his next appointment would be Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[note 1]

Gibraltar

Appointed Governor of Gibraltar by the War Office, gazetted 23 March 1802,[17] the Duke took up his post on 24 May with express orders from the government to restore discipline among the drunken troops. The Duke's harsh discipline precipitated a mutiny by soldiers in his own and the 25th Regiment on Christmas Eve. His brother Frederick, the Duke of York, then Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, recalled him in May 1803 after receiving reports of the mutiny, but despite this direct order he refused to return to England until his successor arrived. He was refused permission to return to Gibraltar for an inquiry and, although allowed to continue to hold the governorship of Gibraltar until his death, he was forbidden to return.[7]

As a consolation for the ending of his active military career when he was 35, he was promoted to the rank of field marshal[4] and appointed Ranger of Hampton Court Park on 5 September 1805.[18] This office provided him with a residence now known as The Pavilion. (His sailor brother, William, with children to provide for, had been made Ranger of Bushy Park in 1797.) The Duke continued to serve as honorary colonel of the 1st Regiment of Foot (the Royal Scots) until his death.[7]

Though it was a tendency shared to some extent with his brothers, the Duke's excesses as a military disciplinarian may have been due less to natural disposition and more to what he had learned from his tutor Baron Wangenheim. Certainly Wangenheim, by keeping his allowance very small, accustomed Edward to borrowing at an early age. The Duke applied the same military discipline to his own duties that he demanded of others. Though it seems inconsistent with his unpopularity among the army's rank and file, his friendliness toward others and popularity with servants has been emphasized. He also introduced the first regimental school. The Duke of Wellington considered him a first-class speaker. He took a continuing interest in the social experiments of Robert Owen, voted for Catholic emancipation, and supported literary, Bible, and abolitionist societies.[7]

His daughter, Victoria, after hearing Lord Melbourne's opinions, was able to add to her private journal of 1 August 1838 "from all what I heard, he was the best of all".[7]

Personal life and interests

Role in the royal succession

Following the death of Princess Charlotte of Wales in November 1817, the only legitimate grandchild of George III at the time, the royal succession began to look uncertain. The Prince Regent (later King George IV and his younger brother Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, though married, were estranged from their wives and had no surviving legitimate children. The king's surviving daughters were all childless and past likely childbearing age. The King's unmarried sons, the Duke of Clarence (later King William IV), Edward, Duke of Kent, and Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, all rushed to contract lawful marriages and provide an heir to the throne. The King's fifth son, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, was already married but had no living children at that time, whilst the marriage of the sixth son, Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, was void because he had married in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act 1772.[19]

Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

For his part the Duke of Kent, aged 50, was already considering marriage, and he became engaged to Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld,[7] who had been the sister-in-law of his now-deceased niece Princess Charlotte. They were married on 29 May 1818 at Schloss Ehrenburg, Coburg, in a Lutheran rite, and again on 11 July 1818 at Kew Palace, Kew, Surrey.[7]

Princess Victoria was the daughter of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and the sister of Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, husband of the recently deceased Princess Charlotte. She was a widow: her first husband was Emich Karl, 2nd Prince of Leiningen, with whom she had had two children: a son, Karl, 3rd Prince of Leiningen, and a daughter, Princess Feodora of Leiningen.

Issue

They had one child, Alexandrina Victoria, born 24 May 1819. He was 51 years old at the time of her birth. The Duke took great pride in his daughter, telling his friends to look at her well, for she would be Queen of the United Kingdom.[7]

Mistresses

Various sources report that the Duke of Kent had mistresses. In Geneva, he had two mistresses, Adelaide Dubus and Anne Moré. Dubus died at the birth of her daughter Adelaide Dubus (1789 – in or after 1832). Anne Gabrielle Alexandrine Moré was the mother of Edward Schenker Scheener (1789–1853). Brought up in Geneva as the ostensible son of Thimothée Schencker, his father promised to find him a post in the UK civil service and in 1809 he was appointed a clerk in the Foreign Office, being retired with a pension in 1826. When his half-sister Victoria became Queen in 1837, with his English wife Harriet Boyn (1781-1852) he returned to Geneva, where he died in 1853. He had no children.[20]

In 1790, while still in Geneva, the Duke took up with "Madame de Saint-Laurent" (born Thérèse-Bernardine Montgenet), the wife of a French colonel. She went with him to Canada in 1791, where she was known as "Julie de Saint-Laurent". She accompanied the Duke for the next 28 years, until his marriage in 1818.[7] The portrait of the Duke by Beechey was hers.[21]

Mollie Gillen, who was granted access to the Royal Archive at Windsor Castle,[22] established that no children were born of the 27-year relationship between Edward Augustus and Madame de Saint-Laurent; although many Canadian families and individuals (including the Nova Scotian soldier Sir William Fenwick Williams, 1st Baronet),[23] have claimed descent from them. Such claims can now be discounted in light of this research.[7]

Canadian Confederation

While Prince Edward lived in Quebec (1791–93) he met with Jonathan Sewell, an immigrant American Loyalist who played trumpet in the Prince's regimental band. Sewell would rise in Lower Canadian government to hold such offices as Attorney General, Chief Justice, and Speaker of the Legislative Assembly. In 1814, Sewell forwarded to the Duke a copy of his report "A plan for the federal union of British provinces in North America." The Duke supported Sewell's plan to unify the colonies, offering comments and critiques that would later be cited by Lord Durham (1839) and participants of the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences (1864).

Edward's 1814 letter to Sewell:

My dear Sewell,

I have had this day the pleasure of receiving your note of yesterday with its interesting enclosure. Nothing can be better arranged than the whole thing is or more perfectly, and when I see an opening it is fully my intention to point the matter out to Lord Bathurst and put the paper in his hands, without however telling him from whom I have it, though I shall urge him to have some conversation with you relative to it. Permit me, however, just to ask you whether it was not an oversight in you to state that there are five Houses of Assembly in the British Colonies in North America. If I am not under an error there are six, viz., Upper and Lower Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the islands of Prince Edward and Cape Breton.

Allow me to beg of you to put down the proportions in which you think the thirty members of the Representatives Assembly ought to be furnished by each Province, and to suggest whether you would not think two Lieutenant-Governors with two Executive Councils sufficient for an executive government of the whole, namely one for the two Canadas, and one for New Brunswick and the two small dependencies of Cape Breton and Prince Edward Island, the former to reside in Montreal, and the latter at whichever of the two (following) situations may be considered most central for the two provinces whether Annapolis Royal or Windsor.

But, at all events, should you consider in your Executive Councils requisite I presume there cannot be a question of the expediency of comprehending the two small islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence with Nova Scotia.

Believe me ever to remain,

With the most friendly regard,

My dear Sewell,

Yours faithfully,

EDWARD[24]

Freemasonry - United Grand Lodge of England

.jpg.webp)

In January 1813, Prince Edward's brother, Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex (sixth son of King George III), became Grand Master of the Premier Grand Lodge of England (aka "The Moderns") on the resignation of his brother, the Prince Regent; and, in December of that year, Prince Edward became Grand Master of the Antient Grand Lodge of England (aka "The Ancients"). In 1811, both Grand Lodges had appointed Commissioners; and over the ensuing two years, articles of Union were negotiated and agreed upon. On 27 December 1813, the United Grand Lodge of England, formed as a result of these negotiations, was constituted at Freemasons' Hall, London with the younger Duke of Sussex as Grand Master. A Lodge of Reconciliation was formed a few weeks prior to reconcile the rituals worked under the two former Grand Lodges.[25]

Later life

The Duke of Kent purchased a house of his own from Maria Fitzherbert in 1801. Castle Hill Lodge on Castlebar Hill, Ealing (West London), was then placed in the hands of architect James Wyatt and more than £100,000 spent (£8.1 million in 2021).[14][26] Near neighbours from 1815 to 1817 at Little Boston House were US envoy and future US President John Quincy Adams and his English wife Louisa. "We all went to church and heard a charity sermon preached by a Dr Crane before the Duke of Kent", wrote Adams in a diary entry from August 1815.[27]

Following the birth of Princess Victoria in May 1819, the Duke and Duchess, concerned to manage the Duke's great debts, sought to find a place where they could live inexpensively. After the coast of Devon was recommended to them they leased from a General Baynes, intending to remain incognito, Woolbrook Cottage on the seaside by Sidmouth.[7]

Death

The Duke of Kent died of pneumonia on 23 January 1820 at Woolbrook Cottage, Sidmouth,[7] and was interred in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[7] He died six days before his father, George III, and less than a year after his daughter's birth.

He predeceased his father and his three elder brothers but, as none of his elder brothers had any surviving legitimate children, his daughter Victoria succeeded to the throne on the death of her uncle King William IV in 1837, and reigned until 1901.

In 1829, the Duke's former aide-de-camp purchased the unoccupied Castle Hill Lodge from the Duchess in an attempt to reduce her debts;[26] the debts were finally discharged after Victoria took the throne and paid them over time from her income.

Legacy

There is a bronze statue of the prince in Park Crescent, London. Sculpted by Sebastian Gahagan and installed in January 1824, the statue is seven feet two inches (2.18 m) tall and represents the Duke in his Field Marshal's uniform, over which he wears his ducal dress and the regalia of the Order of the Garter. He is the namesake of Prince Edward Island, Prince Edward Islands, Prince Edward County, and Duke Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Honours and arms

Honours

- Knight Founder of St. Patrick, 11 March 1783[28]

- Royal Knight of the Garter, 2 June 1786[29]

- Privy Councilor of the United Kingdom, 5 September 1799

- Knight Grand Cross of the Bath (military), 2 January 1815[30]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphic Order (military), 12 April 1815[31]

Arms

As a son of the sovereign, the Duke of Kent had use of the arms of the kingdom from 1801 to his death, differenced by a label argent of three points, the centre point bearing a cross gules, the outer points each bearing a fleur-de-lys azure.[32]

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Explanatory notes

- "The Duke of Kent". The Times. No. 4890. 3 September 1800. p. 2.

We have the pleasure to announce the safe arrival of the Duke of Kent in England. His Royal Highness landed at Plymouth on Sunday evening under a Royal Salute from the Forts, the ships on the Sound, Cawsand Bay and the Hamoaze and set off immediately for Weymouth to pay his respects to their Majesties.

While we rejoice in his safe arrival we cannot but regret that ill health should again have been the cause of his Royal Highness's return to this country, especially when we reflect on the motives which induced him to quit England.

Before his Royal Highness was created Duke of Kent with a suitable income, he had incurred some debts. On his returning to England on finding that he was unable to live in any degree suitable to his rank, and at the same time to discharge his debts, he generously resolved again to go to America, and to remain there, living solely on his pay as an Officer, till his debts were entirely liquidated, to which purpose he gave up the whole of his income allowed him by Government, and in this resolution he persisted, till repeated bilious attacks compelled him to quit that country.

We are sensible that an idea once prevailed that his Royal Highness, in early life, had participated in several of the fashionable vices of the age; but nothing was ever more remote from the truth—for it may be truly said of the Duke of Kent (what can be said of very few men of Rank) that he never was known to be intoxicated, or ever won or lost a farthing at any kind of play in his life; that he never endeavored to seduce the wife of another, or even made a promise he did not do his utmost to perform—his rigid adherence to his word is so remarkable that no consideration has ever induced him to swerve from a promise he has once given. To these good qualities his Royal Highness united a most benevolent disposition; and amidst all his pecuniary embarrassments he has invariably set apart 500l. a year of his income for the relief of private indigence and distress—throughout all British America he was so universally beloved, that the loss of his presence is reckoned one of the greatest misfortunes that could have befallen the country. And we have no hesitation in expressing our conviction, that no measure will more strongly contribute to pacify and reconcile all ranks of people in Ireland, than the presence of his Royal Highness in that country, where we now understand it is the intention of the Government to employ him.

References

- "Royal Burials in the Chapel since 1805". stgeorges-windsor.org. College of St George. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Whitehall, 23 April 1799.

The King has been pleased to grant to His Most Dearly-Beloved Son Prince Edward, and to the Heirs Male of His Royal Highness's Body lawfully begotten, the Dignities of Duke of the Kingdom of Great Britain, and of Earl of the Kingdom of Ireland, by the Names, Styles, and Titles of Duke of Kent, and of Strathern, in the Kingdom of Great Britain, and of Earl of Dublin, in the Kingdom of Ireland. "No. 15126". The London Gazette. 23 April 1799. p. 372. - Whitehall, 17 May 1799.

The King has been pleased to appoint His Royal Highness General Edward Duke of Kent, K.G. to be General and Commander in Chief of His Majesty's Forces in North America, in the Room of General Robert Prescott. London Gazette issue 15133, page 458, published 14 May 1799. - "No. 15840". The London Gazette. 3 September 1805. p. 1114.

- Tidridge, Nathan. Prince Edward, Duke of Kent: Father of the Canadian Crown (Toronto, ON: Dundurn Press, 2013), 90.

- Taube, Michael. A Neglected Royal (Toronto, ON: Literary Review of Canada, 2013), 43.

- Longford, Elizabeth (2004). "Edward, Prince, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767–1820)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8526. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Letter from Lieutenant Colonel von Wangenheim to George III, King, George III's Private Papers, Royal Collection Trust, 18 August 1875, retrieved 11 May 2023

- "No. 12756". The London Gazette. 30 May 1786. p. 242.

- Plaquette commémorative... Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine: «L'Union disposait d'un spacieux local en ville, la Maison Caillate, entre le Molard et Longemalle, et d'un autre à la campagne, aux Eaux-Vives, où l'on se rendait en été. Le local en ville était fort vaste, doté de deux étages, avec un cercle où l'on jouait aux cartes et au billard.»

- Tidridge, Nathan. Prince Edward, Duke of Kent: Father of the Canadian Crown (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2013), 56.

- "No. 13578". The London Gazette. 1 October 1793. p. 876.

- "No. 13641". The London Gazette. 17 April 1794. p. 336.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- " ". The Times. No. 4541. 22 July 1799. p. 3.

- " ". The Times. No. 4880. 22 August 1800. p. 3.

By the arrival of the Packet from America we learn that the Duke of Kent was to embark at Halifax for this country about the 5 August on board of the Assistance, Captain [Robert] Hall, his Royal Highnesses state of health rendering his return to England necessary. Very few Officers have been so constantly kept on foreign service as his Royal Highness, who we have reason to believe is coming home to be appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

- "No. 15464". The London Gazette. 23 March 1799. p. 304.

- "Whitehall, 25 November 1805". The London Gazette. No. 15865. 23 November 1805. p. 1467.

His Majesty has been pleased to grant unto His Royal Highness Edward Duke of Kent the Offices and Places of Keeper and Paler of the House Park of Hampton-Court, and of Mower of the Brakes there, and of the Herbage and Passage of the said Park, with the Wood called Browsings, Windfall Wood, and dead Wood, happening in the said Park; and of all the Barns, Stables, Outhouses, Gardens and Curtilages belonging to the Great Lodge in the said Park, together with the said Lodge itself &c. during his Majesty's pleasure.

- Strachey, Lytton Queen Victoria

- Jones, R. A. (2004). "Scheener, Edward Schencker (1789–1853)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53528. Retrieved 12 November 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gillen, Mollie (1987). "MONTGENET, THÉRÈSE-BERNARDINE". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. VI (1821–1835) (online ed.). University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

She asked the duke only for Sir William Beechey's portrait of him: he sent it in care of the Duc d'Orléans.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - The Prince and His Lady- The Love Story of the Duke of Kent and Madame de St Laurent, Mollie Gillen, Griffin Press Ltd, 1970, pp. 25, 44

- Waite, P.B. (1982). "WILLIAMS, Sir WILLIAM FENWICK". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XI (1881–1890) (online ed.). University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

Williams himself made no effort to discredit this possibility, which would have meant he was Queen Victoria's half-brother.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Journal of the House of Assembly of Upper Canada 1839, page 103

- Beresiner, Yasha (9 October 2008). "Masonic Education – Lodges of Instruction". Pietre-Stones Review of Freemasonry. Masonic Papers. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

The Lodge of Reconciliation was thus formed on 7 December 1813, a few weeks before the actual Union ceremonies and the installation of the Grand Master of the new United Grand Lodge of England were to take place.

- T F T Baker, C R Elrington (Editors) A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7 Victoria County History 1982, pp. 128-131

- Adams, John Quincy (2014). Diary 29, John Quincy Adams Diary: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society. p. 309. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 96

- Shaw, p. 47

- Shaw, p. 182

- Shaw, p. 447

- "Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family". heraldica.org.

- Naftel, W.D. (2005). Prince Edward's Legacy: The Duke of Kent in Halifax: Romance and Beautiful Buildings. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Formac Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88780-648-3.

External links

- Portraits of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Cottage Orné: Woolbrook cottage in May 2009, now the Royal Glen hotel

- MacNutt, W.S. (1983). "Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent and Strathearn". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Nathan Tidridge's Prince Edward, Duke of Kent: Father of the Canadian Crown

GeorgeDawe.jpg.webp)