Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma

Xavier, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, known in France before 1974 as Prince Xavier de Bourbon-Parme, known in Spain as Francisco Javier de Borbón-Parma y de Braganza or simply as Don Javier (25 May 1889 – 7 May 1977), was the head of the ducal House of Bourbon-Parma and Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain.

| Xavier | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke of Parma | |||||

.jpg.webp) Xavier in 1970 | |||||

| Head of the House of Bourbon-Parma | |||||

| Tenure | 15 November 1974 – 7 May 1977 | ||||

| Predecessor | Duke Robert Hugo | ||||

| Successor | Duke Carlos Hugo | ||||

| Born | 25 May 1889 Villa Pianore, Lucca, Kingdom of Italy | ||||

| Died | 7 May 1977 (aged 87) Zizers, Switzerland | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Princess Marie Françoise, Princess of Lobkowicz Prince Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma and Piacenza Princess Marie Thérèse Princess Cécile Marie, Countess of Poblet Princess Marie des Neiges, Countess of Castillo de la Mota Prince Sixtus Henry, Duke of Aranjuez | ||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon-Parma | ||||

| Father | Robert I, Duke of Parma | ||||

| Mother | Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

He was the second son of the last reigning Duke of Parma Robert I and his second wife Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal, although born after his father lost the throne. Educated with austerity at Stella Matutina, he grew up in France, Italy and Austria, where his father had properties. During World War I, he joined the Belgian army, fighting with distinction. With his brother Sixtus he was a go-between in the so-called Sixtus Affair, a failed attempt by his brother-in-law, Emperor Charles I of Austria to negotiate a separate peace with the Allies (1916–1917) through the Bourbon-Parma brothers.

In 1936 Don Alfonso Carlos de Borbón, Duke of Madrid died, ending the male line of Carlist pretenders to the Spanish throne descended from Infante Carlos, Count of Molina. Having no children with his wife, Maria das Neves of Portugal, Don Alfonso Carlos designated her nephew Xavier to succeed him as regent in exile of the Carlist Communion and as Grand Master of the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy.

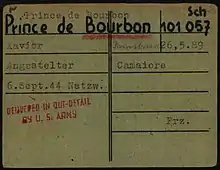

During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), he entered Spain twice and the Carlist troops, known as Requetés, sided with the Nationalist faction of General Franco. He visited the North Front and Andalusia, but was expelled from Spain in 1938. He settled in France at the castle of Bostz, a property of his wife. During World War II, he reenlisted in the Belgian army. After Belgium and France were invaded by the Nazis, he moved to Vichy and took part in the French Resistance. Arrested by the Gestapo in 1941, he was condemned to death for espionage and terrorism. Pardoned by Marshal Pétain, he was confined in Clermont-Ferrand, Schirmeck, Natzwiller and lastly, in September, he was imprisoned in Dachau from which he was freed by the Americans in April 1945.

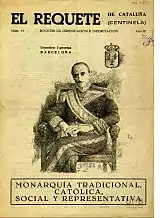

During the 1950s and 1960s he was active in the Carlist movement. In May 1952, persuaded of the need to be appointed king by the National Council of Traditionalist Communion, he agreed to conclude the sixteen years of his regency by being proclaimed King of Spain in Barcelona under the name Javier I. Soon thereafter he was expelled from Spain by order of the Francoist government. At the death of his unmarried nephew Robert of Parma in 1974, Prince Xavier became titular Duke of Parma. By then he was in frail health, having suffered life-threatening injuries in a 1972 traffic accident. He transferred all political authority to his eldest son, Prince Carlos Hugo of Bourbon-Parma, and formally abdicated as the Carlist king in his elder son's favor in 1975.

Road to Spain

Family

Xavier was born to a highly aristocratic Bourbon-Parma family; in the mid-18th century the branch diverged from the Spanish Bourbons, who in turn had diverged from the French Bourbons few decades earlier. Along the patriline Xavier was descendant to the king of France Louis XIV[1] and to the king of Spain Felipe V.[2] Among his great-great-grandparents, Ludovico I was the king of Etruria, Vittorio Emanuele I was the king of Sardinia and the duke of Savoy, Charles X was the king of France, Francesco I was the king of Two Sicilies, Pedro III was the king of Portugal, Maria I was the queen of Portugal and Brazil, and Carlos IV was the king of Spain; among his great-grandparents, Carlo II was the duke of Parma and João VI was the king of Portugal; among his grandparents, Carlo III was the duke of Parma and Miguel I was the king of Portugal. Xavier's father, Robert I (1848–1907) was the last ruling duke of Parma, and Xavier's mother, Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal (1862–1959), was exile-born daughter of the 1834-deposed king of Portugal.

Many of Xavier's uncles and aunts came from European royal or ducal families,[3] though the only one actually ruling was his mother's sister, Infanta Maria Ana of Portugal, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg.[4] The other three were claiming the throne: his mother's brother, the Portuguese Miguelist pretender Dom Miguel, Duke of Braganza,[5] his father's sister, the Carlist queen of Spain Margarita de Borbón-Parma[6] and another sister of his mother, also the Carlist queen of Spain, Infanta Maria das Neves of Portugal.[7] One uncle, archduke Karl Ludwig,[8] was official heir to the throne of Austro-Hungary.[9] Of Xavier's cousins the only two who actually ruled were Elisabeth, the queen consort of Belgium[10] and Charlotte, the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg.[11] Xavier's step-cousin,[12] archduke Franz Ferdinand, was official heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne.[13] Two cousins were legitimist pretenders; along the paternal line Don Jaime, the Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne,[14] and along the maternal line Dom Duarte Nuño, the Miguelist claimant to the Portuguese throne.[15]

Some of Xavier's siblings have married into the ruling European houses and few have actually ruled: these were the cases of his younger sister Zita, who in 1911 married into the imperial Habsburg family to become the empress of Austria and the queen of Hungary in 1916–1918, and this of his younger brother Felix, who in 1919 married into the ducal Nassau family and was the duke-consort of Luxembourg in 1919–1970. Some of Xavier's siblings were closely related to actual rulers: these were the cases of his younger brother René, who in 1921 married into the royal Danish family,[16] this of his younger brother Louis, who in 1939 married into the royal Italian family,[17] and this of his older half-sister Maria Luisa, who in 1893 married into the royal Bulgarian family.[18] Some of Xavier's siblings married into ducal or otherwise distinguished highly aristocratic houses.[19] Six mentally handicapped older half-siblings have never married and three of Xavier's sisters became Benedictine nuns.

Infancy, childhood and youth (before 1914)

Though deposed as Duke of Parma in 1859, Xavier's father kept claiming the title. He retained massive wealth, comprising estates in Italy and Austria; moreover, in the late 19th century the Bourbon-Parma inherited the magnificent Chambord castle.[20] The family, consisting of Robert, his second wife and some 20 children[21] from both marriages lived in two homes, in Pianore and in Schwarzau.[22] They used to spend half a year in each location, shuttling in a special train and taking even children's horses with them.[23] Xavier's childhood was full of serenity, luxury and cheerfulness,[24] though relations with half-siblings from the first marriage were not equally cordial. The Bourbon-Parma were deeply Roman Catholic[25] and essentially French in culture and understanding;[26] another language spoken was German.[27] In his childhood Xavier picked up also Italian – spoken with the Pianore locals, English – spoken with various visitors, Portuguese and Spanish – used in certain relations, and Latin – used in church.[28] The family were frequently visited by guests from the world of aristocracy, books and universities.[29]

In 1899[30] Xavier followed in the footsteps of his older brother Sixte and entered Stella Matutina,[31] a prestigious Jesuit establishment in the Austrian Feldkirch. Though catering to Catholic aristocracy from all over Europe, the school offered Spartan conditions; when later enquired how he survived the Nazi concentration camp, prince Xavier joked: "I attended the Stella. It's not easy to kill us".[32] The school ensured a model of humble religiosity, the staff ensured high teaching standards, and the mix of boys from different countries ensured a spirit of international comradeship. Xavier graduated in the mid-1900s;[33] in 1906[34] moved to Paris,[35] still trailing his older brother and commencing university studies.[36] Unlike Sixte, who studied law, he pursued two different paths: political-economic sciences and agronomy. He completed both, graduating as engineer in agronomy and doctor in politics/economy.[37] The year or years of him completing the curriculum are not clear; one source points to 1914.[38] He has never commenced a professional career.

In 1910 the wealth of the late Robert Bourbon-Parma was divided among the family. Children from the first marriage, and especially Élie, custodian of his handicapped siblings, were allocated most of the real estate; Robert's second wife and children from the second marriage were earmarked hefty financial compensation, usufruct rights and minor properties. Already on his own, Xavier was based in Paris[39] but cruised across Europe. One reason was family business, often with political background; e.g. in 1911 Xavier travelled to Austria to attend the wedding of his sister with archduke Karl Habsburg, heir[40] to the Austro-Hungarian throne; in 1912 he travelled via Spain to Portugal, accompanying his aunt during a Portuguese legitimist plot.[41] Another reason was following his personal interest. Xavier seemed heavily influenced by Sixte, who developed a knack for geographical exploration. In 1909 both brothers travelled to the Balkans;[42] in 1912 they roamed across Egypt, Palestine and the Near East.[43] In 1914 they intended to travel to Persia, India and possibly the Himalayas.[44]

Soldier and diplomat (1914–1918)

News of the Sarajevo assassination reached Xavier and Sixte in Austria, en route to Asia.[45] Enraged by murder of their step-cousin, both brothers intended to enlist in the Austrian army to pursue revenge.[46] Things changed when France declared war on Vienna. Though some of the Bourbon-Parma siblings – Zita, René, Felix and Élie – sided with Austria-Hungary, with males joining the imperial troops, Xavier and Sixte felt themselves thorough Frenchmen. They openly made plans to enlist in the French army, which might have evoked their detention. It took personal appeals from Zita before the Emperor took steps which prevented their incarceration, and allowed them to leave Austria for a neutral country.[47] When back in France Xavier and Sixte indeed volunteered, only to find that French law banned members of foreign dynasties from serving. Determined to fight, they contacted their cousin, Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, who saw to it that both were allowed to serve in the Belgian military.[48] Due to a car accident involving Sixte, however, the brothers joined the ranks of the Belgian army no sooner than late November 1914.[49] Xavier was initially accepted as a private in medical services[50] and was seconded to the 7th artillery regiment.[51] Exact details of his service are not clear; what was left of the pre-war Belgian army served on a relatively calm sector of the frontline in Flanders and France, next to the English Channel. At an unspecified time Xavier was released from the line and assigned to an officer training course, organized by the Belgian general staff, which he completed. By mid-1916 he was sub-lieutenant,[52] later promoted to captain.[53]

In late 1916 Xavier became involved in the Sixtus Affair, a secret Austrian attempt to conclude a separatist peace. The new emperor, Karl I, decided to exploit his family ties and friendship with the Bourbon-Parma brothers, trusting especially in the skills and intelligence of Sixte. As French citizens, both agreed to undertake the mission only upon obtaining the consent of the French government.[54] The role of Xavier is generally considered secondary to that of Sixte, though he was present during some crucial meetings,[55] whether with the French authorities in Paris or with the Austro-Hungarian envoys in Switzerland,[56] and in Vienna;[57] and some scholars do refer to "mediation des princes Sixte et Xavier".[58] Negotiations broke down in early 1917 and the matter seemed closed; leaked by Clemenceau in May 1918, it turned into a political crisis and a scandal, which damaged the prestige of the young emperor. Xavier and Sixte, at that time in Vienna, were considered endangered, menaced either by the Austrian foreign minister Czernin's willingness to eliminate witnesses, or as victims of popular wrath.[59] The incident is considered "perhaps the ultimate example of amateurish aristocratic diplomacy gone awry during the First World War",[60] although none of the sources consulted tends to blame Xavier for the final failure. It is not clear whether he returned to military service afterwards. At the moment of the armistice he was a major in the Belgian army,[61] awarded the French Croix de Guerre,[62] the Belgian Croix de Guerre, and the Belgian Ordré de Léopold.[63]

Plaintiff and husband (1920s)

Immediately after the war Xavier was engaged in assisting Zita and Karl following their deposition. In 1919 together with Sixte he travelled to England and contacted king George V; the British support materialized as a liaison officer, dispatched to the republican Austria to assist the unhappy couple on their route to exile.[64] However, it soon turned out that it was his own business which attracted most of Xavier’s attention. Following wartime financial turmoil and expropriations of some family estates, economic prospects of both brothers seemed rather bleak. As a counter-measure, they decided to challenge the French state, which in 1915 seized Chambord as property of Élie, the Austrian officer; the Versailles Treaty stipulations allowed to conclude the seizure legally if combined with paying compensation fee. Sixte and Xavier sued; they claimed that the family-agreed 1910 partition, based on the Austrian concept of an indivisible majorate, was not applicable in the French law, and that the Chambord property should be divided; they claimed also that as volunteers to the French and Belgian armies, they should be exempted from expropriation procedure. Centred on fortune-worth Chambord property, in fact the lawsuit was directed against Élie. In 1925 the court accepted brothers’ point of view, the decision immediately appealed by their half-brother. In 1928 the case was overturned in favor of Élie, the decision appealed by both brothers. In 1932 the Court of Cassation upheld the 1928 decision, which eventually left Xavier and Sixte frustrated in their bid.[65]

Resident in Paris and living off the family wealth remaining, Xavier reached his mid-30s when he was attracted[66] to Madeleine de Bourbon-Busset, 9 years his junior, daughter to Count de Lignières and descendant to a cadet branch of the French Bourbons. The Bourbon-Bussets have been related to a centuries-old aristocratic controversy; historically regarded non-dynastic as set up in the 15th century by an illegitimate relationship, by enemies the branch was lambasted as bastards.[67] Would-be marriage of prince Xavier and Madeleine might have resulted in stripping their children off Bourbon-Parma ducal heritage rights, depending upon decision of head of the branch. Since the death of Robert, it was Élie who headed the family; he declared the would-be marriage non-dynastic and morganatic.[68] Despite this stand, Xavier wed Madeleine in 1927[69] and some newspapers titled her "princesse".[70]

As the Bourbon-Bussets enjoyed significant wealth the marriage changed financial status of Xavier, especially that Madeleine had no living older brothers.[71] The couple settled in Bostz castle,[72] where Xavier managed the rural economy of his in-laws;[73] their first child was born in 1928, to be followed by the other 5 throughout the 1930s.[74] Following the 1932 death of his father-in-law, Xavier became head of the family business, crowned with the Lignières castle. Little is known of his public activity at that time, except that he was engaged in various non-political though conservatism-flavored Catholic initiatives.[75] Perhaps the most happy period of his life was punctured by the premature 1934 death of Sixte, for decades Xavier’s best friend and sort of a mentor.

From prince Xavier to Don Javier (1930s)

Exact political views of Xavier are not clear; until the mid-1930s he did not engage in openly political activity, though he figured prominently in some French royalist initiatives.[76] Himself son of a deposed ruler and his own sister deposed as empress, he had some relatives – associated with France, Spain and Portugal – engaged in legitimist politics, though others – associated with Luxembourg, Belgium, Denmark and Italy – fit rather in a general liberal-democratic monarchist framework. None of the sources consulted provides information on his views on ongoing French politics.[77] Few note that his brother Sixte was a legitimist, who in scientific dissertation advanced rights of the Spanish Bourbons to the crown of France;[78] on the other hand, his half-brother Élie openly abandoned the legitimist outlook.[79] Some scholars claim that prince Xavier remained within "más pura doctrina tradicionalista";[80] others suggest that he nurtured democratic ideas.[81]

Though his paternal uncle was until 1909 the legitimist claimant to the throne of Spain, succeeded by prince Xavier’s own cousin, prince Xavier – a Frenchman at heart[82] – himself did not reveal any particular interest in Spanish issues, even though he maintained close links with his cousin, in the 1920s resident in Paris.[83] This changed when Jaime III died unexpectedly in 1931 and was succeeded in his Carlist claim by Alfonso Carlos I. Resident in Vienna, octogenarian and childless, Alfonso Carlos was doubly related to the Bourbon-Parmas;[84] the two families remained on close terms.[85] His ascendance to the Carlist claim was from the onset plagued by the succession problem, as it was already evident that the Carlist dynasty would extinguish. As measure to address the issue, in the early 1930s Alfonso Carlos pondered upon reconciliation with the Alfonsine branch. It is not clear whether he commenced talks with other members of the family about a strictly Carlist succession in parallel, as option B, or whether he embarked on this course having abandoned the plans of dynastic agreement in 1934-1935.[86]

Following the death of Sixte in 1934 Xavier became the most senior Bourbon-Parma partner of Alfonso Carlos.[87] The two must have discussed the question of Carlist succession extensively, yet there is no information on details. In particular, it is not clear whether Alfonso Carlos suggested that Xavier succeeds him as a king – proposal possibly rejected by the Bourbon-Parma, or whether regency was the option preferred from the onset. Scholars speculate that it was prince Xavier’s legitimism, Christian spirit, modesty, impartiality and lack of political ambitions which prompted Alfonso Carlos to appoint him as a future regent.[88] What prompted Xavier to accept the proposal remains unclear. Some suspect that he gave in to the pressure of his uncle, and considered accepting the regency as his family, legitimist and Christian duty. In any case, Xavier probably viewed his future regency, announced in the Carlist press in April 1936 and to commence after death of Alfonso Carlos, in terms of months rather than years. It was supposed to provide royal continuity before a general Carlist assembly appoints a new king.[89]

Regent

Wartime leader (1936–1939)

Contrary to expectations, the Spanish February 1936 elections produced victory of the Popular Front and the country embarked on a proto-revolutionary course. The Carlists first commenced preparations to their own rising, and then entered into negotiations with the conspiring military. For prince Xavier events took an unexpected turn. Instead of calmly familiarizing himself with the Spanish Carlists to organize smooth election of a new king following anticipated death of Alfonso Carlos, the latter asked him to supervise the conspiracy.[90] Prince Xavier, in Spain known as Don Javier, set his headquarters in Sant-Jean-de-Luz and from June to July kept receiving Carlist politicians. In terms of negotiations with the generals, he adopted an orthodox Carlist, rigorous and intransigent stand. Though some Carlists pressed almost unconditional adherence to military conspiracy,[91] Don Javier demanded that a partnership political deal is concluded first.[92] He was eventually outmaneuvered[93] and the Carlists joined the coup on vague terms;[94] their key asset was the pre-agreed Jefe Supremo del Movimiento, General Sanjurjo, who in earlier Lisbon talks with Don Javier pledged to represent the Carlist interests.[95]

The death of Sanjurjo was a devastating blow to Carlist plans; political power among the rebels slipped to a group of generals, indifferent if not skeptical about the Carlist cause. Don Javier, in the late summer watching the events unfold from Sant-Jean-de-Luz, was supervising increasing Carlist military effort,[96] yet was unable to engage in discussion with the generals.[97] Following the death of Alfonso Carlos on 1 October Don Javier was declared the regent. He found himself heading the movement during overwhelming turmoil. Denied entry to Spain,[98] he limited himself to written protests over the marginalisation of Carlism within the Nationalist faction.[99] Faced with growing pressure to integrate the Carlist organization within a new state party in early 1937, he advocated intransigence, but was again outmaneuvered into a silent wait-and-see stance.[100] Following the Unification Decree he entered Spain in May; sporting a requeté general's uniform, and in apparent challenge to Franco he toured the front lines,[101] lifting Carlist spirits.[102] A week later he was expelled from Spain.[103]

_-_Fondo_Car-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp)

Following another brief visit and another expulsion in late 1937,[104] Don Javier aimed at safeguarding Carlist political identity against the unification attempts, though he refrained also from burning all bridges with the emerging Francoist regime. He permitted few trusted Carlists to sit in the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS) executive, but expelled from the Comunión Tradicionalista those who had taken seats without his consent. In full accord with the Carlist leader in Spain, Manuel Fal Conde, in 1938–1939 Don Javier managed to prevent incorporation into the state party, thus the intended unification turned into absorption of offshoot Carlists. On the other hand, Don Javier failed to prevent the marginalisation of Carlism, the suppression of its circulars, periodicals and organizations, and failed to avert growing bewilderment among rank and file Carlists. In 1939 he repeated his offer to Franco in Manifestación de ideales, a document was put forth recommending immediate restoration of Traditionalist monarchy with a transitory collective regency, possibly encompassing Don Javier and Franco.[105] In historiography there are conflicting accounts of this episode,[106] yet there was no follow-up on part of Franco.

Soldier, incommunicado, prisoner (1939–1945)

_in_France_1939-1940_F4484.jpg.webp)

Upon the outbreak of World War II Prince Xavier resumed his duties in the Belgian Army,[107] serving as major[108] in his old artillery unit. As the Germans advanced swiftly, the Belgians were pushed back to Flanders, towards the English Channel. Incorporated into the French troops, the regiment was withdrawn into Dunkerque.[109] In the mayhem that followed, the Belgians did not make it to the British evacuation ships and Don Javier became a German POW.[110] Released promptly, he returned to the family castles of Lignières in Berry and of Bostz, in Besson dans l’Allier.[111] The properties were divided by the demarcation line, Lignières in the occupied zone and Bostz in the Vichy zone.[112]

In late 1940 and early 1941, Prince Xavier assisted in opening the so-called "Halifax-Chevalier negotiations", a confidential correspondence exchange between the British Foreign Secretary and the Petain-government's education minister, centred mostly on working out a modus vivendi between the British and French colonies.[113] The exact role of Prince Xavier is unclear. Some scholars claim he served as an intermediary, trusted by the British royal family,[114] including King George VI, and by Pétain;[115] as he did not leave France, it seems that he wrote letters which provided credibility for the envoys sent. Though the episode is subject to controversy, by some viewed as a proof of Pétain's double game and by some largely as a hagiographic mystification,[116] the debate hardly relates to the role of Xavier.

In the early 1940s, Prince Xavier was increasingly isolated from Spanish affairs; neither he nor the Spanish Carlists were permitted to cross the frontier, while correspondence remained under wartime censorship. Documents he passed, the most notable of which was the Manifiesto de Santiago (1941),[117] urged that intransigence, though not openly rebellious anti-Francoist actions, be maintained. With the regent, and periodically detained Fal, largely incommunicados, Carlism decayed into bewilderment and disorientation.[118]

In 1941–1943 Prince Xavier lived in political isolation, devoting time to his family and managing the Bourbon-Parma fortune. In 1941 he inherited from his late aunt the Puchheim castle in Austria.[119] Prince Xavier became increasingly sympathetic to the anti-Pétain opposition and, via local priests, maintained informal contact with district Resistance leaders. At one point[120] he joined works of the Comité d'Aide aux Réfractaires du STO and welcomed labor camp escapees in wooden areas of his estates, providing basic logistics and setting up shelters for the sick in his library.[121] When two of them were detected and detained, Prince Xavier cycled to Vichy[122] and successfully sought their release.[123] Exposing himself, following a surveillance period in July he was arrested by the Gestapo.[124] Sentenced to death for espionage and terrorism, he was pardoned by Pétain; first confined in Clermont-Ferrand, Schirmeck and Natzwiller, in September he was finally imprisoned in Dachau.[125][126] The Nazis asked Franco about his fate; the Caudillo declared total disinterest.[127] Periodically condemned to the starvation bunker,[128] when freed by the Americans in April[129] 1945, Prince Xavier weighed 36 kg.[130]

Re-launch (1945–1952)

Having returned to health, in late summer of 1945 prince Xavier testified at the trial of Pétain; his account was largely favorable for the marshal.[131] In December he clandestinely entered Spain for a few days.[132] In a series of meetings held mostly in San Sebastián, the regent and the Carlist executive agreed re-organisation basics of the Carlist structures. Don Javier fully confirmed the authority of Fal Conde and affirmed the intransigent political line, formulated in a 1947 document known as La única solución.[133] It was based on non-collaborative though also non-rebellious stand versus Francoism,[134] refusal to enter into dynastic negotiations with the Alfonsine branch, and hard line versus those who demonstrated excessive support for own Carlist royal candidates, even if theoretically they did not breach loyalty to Don Javier’s regency.[135] With the rank and file Don Javier communicated by means of manifestos, read during Carlist feasts and urging loyalty to Traditionalist values.[136] He also pretended to headship of the Borbon-Parmas.[137]

In the late 1940s the policy of Don Javier and Fal Conde, dubbed javierismo or falcondismo, was increasingly contested within the Comunión. The Sivattistas pressed for terminating the regency and for Don Javier to declare himself the king. They suspected that the overdue regency was an element of Don Javier’s policy towards Franco; according to them, the regent intended to ensure the crown for the Bourbon-Parma by means of appeasement rather than by means of open challenge.[138] In particular they were enraged by allegedly ambiguous stand versus the proposed Francoist Law of Succession,[139] considering it an unacceptable backing of the regime.[140] On the other hand, the possibilists were getting tired of what they perceived as ineffective intransigence and lack of legal outposts, recommending more flexible attitude.[141] Especially following the 1949 news about Franco’s negotiations with Don Juan, Don Javier found himself under pressure to assume a more active stance.[142]

_Golden_Fleece_Variant.svg.png.webp)

Don Javier and Fal stuck to rigorous discipline and dismissed Sivatte from Catalan jefatura,[143] though they also tried to reinvigorate Carlism by permitting individual participation in local elections,[144] seeking a national daily[145] or building up student and workers’ organizations.[146] However, gradually also Fal was getting convinced that the regency was a burden rather than an asset. There were almost no calls to terminate it as initially envisioned by Alfonso Carlos, i.e. by staging a grand Carlist assembly, and there are no signs that Don Javier contemplated such an option; almost all voices called for him simply to assume monarchic rights himself.[147] During the 1950 tour across Vascongadas[148] and 1951 one across Levante he still tried to maintain low profile,[149] but in 1952 Don Javier decided to bow to the pressure, apparently against his own will and considering it another cross to bear. During the Eucharistic Congress in Barcelona he issued a number of documents, including a manifesto to his followers and a letter to his son; in vague terms they referred to "assumption of royalty in succession of the last king", though also to pending "promulgation at the nearest opportunity"[150] and with no mention about the regency.[151]

King

Rather not a king (1952–1957)

The Carlist leaders were exhilarated and made sure that the Barcelona 1952 declaration, presented as end of the regency and commencing the rule of king Javier I, gets distributed across the party network; upon receiving the news, the rank and file got euphoric. However, the very next day Don Javier shared comments which put that understanding in doubt. When some time later approached by the Minister of Justice, he declared having signed no document and explained that his statement in no way implied he had proclaimed himself a king.[152] These assurances did not work with the Francoist regime, and in a matter of hours Don Javier was promptly expelled from Spain.[153]

The years of 1953–1954 provided a contrasting picture: the Carlist leaders boasted of having a new king,[154] while Don Javier withdrew to Lignières, reducing his political activity to receiving guests and to correspondence. In private[155] he played down what had already become known as "Acto de Barcelona", dubbing it "un toutté petite ceremonie".[156] Carlist dissenters, temporarily silenced, started to be heard again.[157] Don Javier seemed increasingly tired of his role and leaning towards a dynastical understanding with Don Juan.[158] His brief early 1955 visit to Spain en route to Portugal fuelled angry rumors of forthcoming rapprochement with the Alfonsists as Don Javier made some ambiguous comments,[159] named the 1952 statement "a grave error" and declared having been bullied into it. At this point relations between him and Fal reached the lowest point; Fal, attacked from all sides and feeling no royal support, resigned.[160] According to some scholars, Don Javier sacked him in "a rather cowardly, backhand manner".[161] Fal was soon replaced by a collegial executive. In late 1955 Don Javier issued a manifesto which declared the Carlists "custodians of patrimony" rather than political party seeking power[162] and in private considered his royal claim a hindrance to alliance of all reasonable people.[163] The year of 1956 proved convulsing, with a number of contradictory declarations following one another in circles;[164] one episode cost Don Javier another expulsion from Spain.[165]

The apparent stalemate was interrupted by emergence of a new force. The young Carlists, disappointed with vacillating Don Javier, focused on his oldest son Hugues instead.[166] Entirely alien to politics and at the time pursuing PhD in economics in Oxford, he agreed to throw himself into the Spanish affairs. Don Javier consented to his 1957 appearance on the annual Montejurra gathering,[167] where the young prince, guided by his equally young aides, made explicit references to "my father, the king".[168] As prince Hugues was ignorant as to Carlism and he barely spoke Spanish, it seems that his father has never considered him own successor,[169] eager rather to free himself and the entire family from the increasingly heavy Carlist burden.[170] It is not clear what he thought about his son unexpectedly engaging in Spanish politics; perhaps he felt relieved having found a replacement or support. To many, it seemed that he "had given up prevaricating".[171]

Rather a king (1957–1962)

Under leadership of José María Valiente and with the consent of Don Javier, the collegial Carlist executive commenced cautious collaboration with the regime. The young entourage decided to introduce Hugues as representing a new strategy and presenting an offer to Franco.[172] According to another interpretation, Don Javier saw his son's involvement as an opportunity to consider new strategies for long-term gains, and changed course in the hope that the regime might one day crown the younger prince. Still another view was that the changing political course and the political coming of age of Hugues simply coincided.[173] One way or another, starting in 1957 Don Javier gradually permitted his son to assume an increasing role within Carlism.

In the late 1950s Don Javier firmly abandoned any discussion of reconciliation with the Alfonsinos.[174] He instructed that harsh measures be taken against those who approached them.[175] However, he remained respectful towards Don Juan and avoided open challenge,[176] He also stopped short of explicitly claiming the kingly title.[177] He supported Valiente – his position gradually reinforced formally up to the new Jefe Delegado in 1958–1960[178] – in attempts to eradicate internal forces of rebellion against collaboration,[179] and to combat new openly secessionist groups.[180] Though 20 years earlier he expelled from the Comunión those who had accepted seats in Francoist structures, at the beginning of the sixties Don Javier viewed the appointment of five Carlists to the Cortes as the success of the collaborationist policy,[181] especially because the Franco regime permitted new Carlist legal outposts, and the movement participated openly in the public discourse.

Another milestone came in 1961–62. First, in a symbolic gesture Don Javier declared Hugues "Duque de San Jaime", a historic title borne by Alfonso Carlos; then, he instructed his followers to envision the prince as the embodiment of "a king".[182] Hugues, legally renaming himself "Carlos Hugo",[183] settled in Madrid and set up his Secretariat, a personal advisory body.[184] Yet for the first time in history, a Carlist heir officially lived in the capital and openly pursued his own politics. From this moment onwards, Don Javier was increasingly perceived as ceding daily business to his son and merely providing general supervision from the back seat. Carlos Hugo gradually took control of communication channels with his father, replacing him also as a key representative of the House of Bourbon-Parma in Spain. Moreover, the three daughters of Don Javier, all in their 20s, with apparent consent of their father engaged themselves in campaigns intended to enhance the standing of their brother with the Spanish public; the younger son of Don Javier, Sixte, soon followed suit.

King, the father (1962–1969)

Carlos Hugo and his aides embarked on an activist policy, launching new initiatives and ensuring that the young prince gets increasingly recognized in national media. In terms of political content the group started to advance heterodox theories, focused on society as means and objective of politics. In terms of strategy, until the mid-1960s it was formatted as advances towards the socially-minded, hard Falangist core; later it started to assume an increasingly Marxist flavor. Orthodox Traditionalists grew increasingly perturbed by Carlos Hugo's active political advances toward the socially-minded, hard Falangist core, which assumed an increasingly Marxist flavor. They tried to alert Don Javier.[185] However, Don Javier gave them repeated assurances that he maintained full confidence in Carlos Hugo.[186] In 1967 Don Javier confirmed that nothing need be added to the Carlist dogma of "Dios, Patria, Fueros, Rey".[187] Yet he also affirmed that new times required new practical concepts.[188] He endorsed subsequent waves of structural changes, and declared some personal decisions.[189] By the mid-1960s Don Javier allowed the Comunión in Carlos Hugo's control and that of his supporters.[190] In the so-called Acto de Puchheim of 1965, for the first time Don Javier explicitly called himself "rey",[191] and consistently claimed that title henceforth.

Such writers as Josep Carlos Clemente and Fermín Pérez-Nievas Borderas maintain that Don Javier was fully aware and entirely supportive of the transformation of Carlism triggered by Carlos Hugo, helped among others by Artur Juncosa Carbonell, intended as renovation of genuine Carlist thought and as shaking off Traditionalist distortions.[192]

Another group of scholars claim that the aging Don Javier, at that time in his late 70s, was increasingly detached from Spanish issues and substantially unaware of the political course sponsored by Carlos Hugo. They argue that he was, perhaps, manipulated – and at later stages even incapacitated – by his son and two daughters, who intercepted incoming correspondence and re-edited their father's outgoing communications.[193]

Another group of scholars largely refrain from interpretation, confining itself to referring readers to correspondence, declarations and statements.[194]

As late as 1966 Don Javier continue to court Franco,[195] but the years of 1967–1969 re-defined his relation with Carlism and with Spain. In 1967 he accepted the resignation of Valiente,[196] the last Traditionalist bulwark in the executive, and entrusted political leadership of the Comunión to a set of collegial bodies dominated by hugocarlistas; the move marked their final victory in the struggle to control the organization.

In 1968 Carlos Hugo was expelled from Spain;[197] In a gesture of support, a few days later Don Javier flew to Madrid and was promptly expelled – for the fifth time.[198][199] This episode marked the end of an increasingly sour dialogue with the regime and the Carlist shift to unconditional opposition;[200]

In 1969 the Alfonsist prince Juan Carlos de Borbón was officially introduced as the future king and successor to Franco, with the title Prince of Spain; the ceremony marked the ultimate crash of the Bourbon-Parmas' hopes for the crown.[201] When Franco died in 1975, Juan Carlos did indeed become king of Spain.

Old king, former king (1969–1977)

Resident mostly at Lignières, Don Javier withdrew,[202] issuing sporadic manifestos, read by his son at Carlist gatherings.[203]

In 1972 Don Javier suffered life-threatening injuries resulting from a traffic accident[204] and formally transferred all political authority to Carlos Hugo.[205] In 1974, upon the childless death of his half-nephew Prince Robert, Duke of Parma, Don Javier ascended as head of the Bourbon-Parmas and assumed the Duke of Parma title. On the one hand, he was in a position to enjoy family life; though his four younger children did not marry, the elder two did, the marriages producing eight grandchildren (born between 1960 and 1974).[206] On the other hand, family relations were increasingly subject to political tension. While Carlos Hugo, Marie-Thérèse, Cécile and Marie des Neiges formed one team advancing the progressive agenda, the oldest daughter Françoise Marie, the youngest son Sixte, and their mother Madeleine opposed the bid. Sixte, in Spain known as Don Sixto, openly challenged his brother;[207] he declared himself the standard-bearer of Traditionalism and started building his own organization.[208]

In 1975 Don Javier abdicated as the Carlist king in favor of Carlos Hugo[209] and according to a source, he would have expelled Sixto from Carlism for refusing to recognize the decision.[210] It is not clear what his view on the commencing Spanish transición was; following the 1976 Montejurra events he lamented the dead, officially disowned the political views of Don Sixto and called for Carlist unity.[211] However, in a private letter, Don Javier claimed that at Montejurra "the Carlists have confronted the revolutionaries", which has been interpreted as the followers of Don Sixto being the real Carlists according to Don Javier.[212]

Early March 1977 proved convulsive. On Friday 4th, accompanied by his son Sixto, he was interviewed by the Spanish press and his responses showed Carlist orthodoxy. That same day he issued a declaration certified by a Paris notary objecting to his name being used to legitimize a "grave doctrinal error within Carlism", and implicitly disowned the political line promoted by Carlos Hugo.[213] In order to justify that declaration, Carlos Hugo alerted the police that his father had been abducted by Sixto, an accusation which was denied publicly by Don Javier himself, who had to be hospitalized heavily affected by the scandal generated.[214] Shortly afterwards Don Javier issued another declaration, certified by a different Paris notary, confirming his oldest son as "my only political successor and head of Carlism".[215] Then it was Doña Madalena who declared that her husband had been taken by Carlos Hugo from hospital against medical advice and his own will, and that Carlos Hugo had threatened his father to obtain his signature on the second declaration.[216] Eventually Don Javier was transferred to Switzerland, where he soon died. The widow blamed the oldest son and three daughters for his death.[217]

Reception and legacy

Barely noted in Spain until the Civil War,[218] also afterwards Don Javier remained a little known figure, partially the result of censorship; Franco considered him a foreign prince.[219] Among European royals he was respected but politically isolated.[220] In the Carlist realm he grew from obscurity to iconic status, yet since the late 1950s he was being abandoned by successive groups, disappointed with his policy.[221] Disintegration of Carlism accelerated after Don Javier's death; Partido Carlista won no seats in general elections and in 1979 Carlos Hugo abandoned politics.[222] This was also the case of his three sisters,[223] though Marie Therese became a scholar in political sciences[224] and advisor to Third World politicians.[225] Sixte is heading Comunión Tradicionalista, one of two Traditionalist grouplets in Spain, and poses as a Carlist standard-bearer.[226] The oldest living grandson of Don Javier, Charles-Xavier, styles himself as the head of the Carlist dynasty, oddly enough, without claiming the Spanish throne.[227] In France a grouplet referred to as Lys Noir[228] called him in 2015 a "king of France for tomorrow".[229] The group is classified by some as Far Right[230] and by some associated with Trotsky, Mao and Gaddafi.[231]

In partisan discourse Don Javier is generally held in high esteem, though Left-wing Partido Carlista militants[232] and Right-wing Traditionalists offer strikingly different pictures of him. Authors admitting their Hugocarlista pedigree claim that from his youth Don Javier has nurtured democratic, progressive ideas,[233] and in the 1960s he lent his full support to renovation of Carlist thought.[234] Authors remaining within the Traditionalist orthodoxy suggest that although generally conservative, but in his 70s impaired by age, bewildered by Vaticanum II, misled and possibly incapacitated by his children, Don Javier presided over destruction of Carlism.[235] A few go farther, claiming that evidence points to Don Javier having been fully supportive of the course sponsored by his son,[236] they either talk about "deserción de la dinastía"[237] or – with some hesitation – point to treason.[238] Some, highly respectful though disappointed by Don Javier's perceived ineptitude and vacillation as a leader, consider him a candidate for sainthood rather than for kingship.[239]

In historiography Prince Xavier has earned no academic monograph yet; books published fall rather into hagiography.[240] Apart from minor pieces related to the Sixtus Affair, Chambord litigation and Halifax-Chevalier negotiations, he is discussed as a key protagonist in various works dealing with Carlism during the Francoist era. There are four PhD dissertations discussing post-civil-war Carlism, yet they offer contradictory conclusions. One[241] presents Don Javier as a somewhat wavering person who eventually endorsed changes to be introduced by Carlos Hugo.[242] One[243] carefully notes his "peculiar position" yet it cautiously claims he kept backing the transformation.[244] Two[245] point to his "contradictory personality" and admit that his stand "might seem confusing", though they claim that he was generally conservative[246] and was faithful to Traditionalist principles,[247] Don Javier was misguided and manipulated,[248] inadvertently legitimizing the change he did not genuinely support.[249] Some hints suggest that he never seriously contemplated his own royal bid, and headed Carlism as a cultural-spiritual movement, perhaps modelled on French legitimism.[250]

At least since 1957 Don Javier purported to exercise the kingly prerogative as a fount of honour, occasionally conferring Carlist chivalric orders, such as the Legimitad Proscrita, upon Valiente, Fal and Zamanillo; in 1963 he conferred the Gran Cruz of the same order on his wife.[251] Don Javier has also created and conferred a number of aristocratic titles, but with one exception (Fal Conde) only for members of his family: Duque de Madrid and Duque de San Jaime for Don Carlos Hugo; Condesa de Poblet for Doña Cecilia; Condesa del Castillo de la Mota for Doña María de las Nieves; Duque de Aranjuez for Don Sixto.[252]

Children

- Princess Marie Françoise of Bourbon-Parma, born on 19 August 1928, married Prince Edouard de Lobkowicz (1926–2010) and had issue.

- Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma, 8 April 1930 – 18 August 2010 (aged 80), married Princess Irene of the Netherlands (born 1939) and had issue.

- Princess Marie Thérèse of Bourbon-Parma, 28 July 1933 – 26 March 2020 (aged 86). Victim of COVID-19.

- Princess Cécile Marie of Bourbon-Parma, 12 April 1935 – 1 September 2021 (aged 86).

- Princess Marie des Neiges of Bourbon-Parma, born on 29 April 1937.

- Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma, born on 22 July 1940.

In fiction

The television series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles presents Xavier (played by Matthew Wait) and his brother Sixtus (played by Benedict Taylor) as Belgian officers in World War I who help the young Indiana Jones.

Writings

- La République de tout le monde, Paris: Amicitia, 1946

- Les accords secrets franco-anglais de décembre 1940, Paris: Plon, 1949.

- Les chevaliers du Saint-Sépulcre, Paris: A. Fayard, 1957.

Honours

.svg.png.webp) Calabrian House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies Knight Grand Cross of Justice of the Calabrian Two Sicilian Order of Saint George[253]

Calabrian House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies Knight Grand Cross of Justice of the Calabrian Two Sicilian Order of Saint George[253].svg.png.webp) Belgium: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[254]

Belgium: Knight Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold[254].svg.png.webp) Belgium: Croix de Guerre[255]

Belgium: Croix de Guerre[255] France: Croix de Guerre[256]

France: Croix de Guerre[256] : Sovereign Knight of the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy

: Sovereign Knight of the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy

Ancestry

See also

Footnotes

- in the 9th generation; Xavier was son of Roberto I de Parma (1848–1907), himself son of Carlos III de Parma (1823–1854), himself son of Carlos II de Parma (1799–1883), himself son of Luis de Etruria (1773–1803), himself son of Fernando I de Parma (1751–1802), himself son of Felipe I de Parma (1720–1765), himself son of Felipe V of Spain (1683–1746), himself son of Louis, Grand Dauphin (1661–1711), himself son of Louis XIV of France (1638–1715)

- in the 7th generation, Xavier was son of Roberto I de Parma (1848–1907), himself son of Carlos III de Parma (1823–1854), himself son of Carlos II de Parma (1799–1883), himself son of Luis de Etruria (1773–1803), himself son of Fernando I de Parma (1751–1802), himself son of Felipe I de Parma (1720–1765), himself son of Felipe V of Spain (1683–1746)

- like Nassau, Habsburg-Lothringen, Wittelsbach, Braganza, Borbon-Dos Sicilias and Thurn-und-Taxis

- in 1905–1912, as duchess consort; she was married to Wilhelm IV, Grand Duke of Luxembourg

- claiming 1866–1920

- she was married to the Spanish Carlist pretender Don Carlos, claiming 1868–1909

- she was married to another Spanish Carlist pretender Don Alfonso Carlos, claiming 1931–1936

- married to the sister of Xavier’s mother

- in 1889–1896

- daughter of Xavier’s mother’s sister, ruling 1909–1934

- daughter of another Xavier’s mother’s sister, ruling 1919–1964

- archduke Franz Ferdinand was the son of Xavier’s uncle Karl Ludwig, though with his first wife

- from 1896 till his death in Sarajevo in 1914

- claiming 1909–1931

- claiming 1927–1976

- and was the father of Anne, later to become a Romanian queen-on-exile; she married in 1948, when the groom, Mihai I, was already deposed

- the bride was daughter of the ruling Italian king and sister of the future last king of Italy

- she gave birth to the later Bulgarian tsar, Boris III, ruling 1918–1943

- these were the cases of Don Javier’s older half-brother Elias, who in 1903 married into the archducal Austrian Habsburg-Lothringen family, this of his older brother Sixte, who in 1919 married into the French ducal la Rochefoucauld family, this of his youngest brother Gaetan, who in 1931 married into the Austrian ducal Thurn-und-Taxis family, and this of his younger sister Beatrice, who in 1909 married into the Italian Lucchesi-Palli family, also of ducal descendance

- the castle, in a number of rankings considered No. 1 among castles in the Loire valley, was bequeathed by the legitimist claimant to the throne of France, Count of Chambord, to the Bourbon-Parmas. The older sister of Count of Chambord, Louise Marie, was married to Carlo, duke of Parma; she was mother of Robert Bourbon-Parma and the paternal grandmother of prince Xavier, see Les lys et la republique service, available here, Franz de Burgos, Domaine de Chambord : Histoire d’une spoliation, [in:] Vexilla Galliae service 12.02.15, available here

- the actual number or kids living together kept changing. Robert had 24 children, 12 from the first and 12 from the second marriage, born between 1870 and 1905. Some died in early infancy, some left the family home when Xavier was a toddler, and some were born after Xavier had left

- James Bogle, Joanna Bogle, A Heart for Europe: The Lives of Emperor Charles and Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary, Leominster 1990, ISBN 9780852441732, p. 17

- Bogle, Bogle 1990, p. 17

- Bogle, Bogle 1990, pp. 17–18

- largely thanks to the maternal grandmother of Xavier, Bogle, Bogle 1990, pp. 17, 19

- Bogle, Bogle 1990, p. 15

- Xavier’s mother, though of Portuguese descendance, was from infancy brought up in the German-speaking environment

- Bogle, Bogle 1990, p. 18

- Bogle, Bogle 1990, p. 17

- some sources claim in 1897, Aproximación biográfica a la figura de Don Javier de Borbón Parma (1889–1977), [in:] Portal Avant! 08.12.02, available here Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Beate Hammond, Jugendjahre grosser Kaiserinnen: Maria Theresia – Elisabeth – Zita, Wien 2002, ISBN 9783800038411, p. 121

- Erich Feigl, Zita de Habsbourg: Mémoires d'un empire disparu, Paris 1991, ISBN 9782741302315, p. 110. Interestingly, in the 1940s prince Xavier sent his first son to an equally Spartan school, a Benedictine establishment in Calcat, with poor heating and no runnig water, Francisco M. de las Heras y Borrero, Carlos Hugo, el rey que no pudo ser, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788495009999, p. 19

- see dynastie.capetienne service, available here

- according to some authors, he was educated also in the German Carlsberg, Josep Carles Clemente Muñoz, La Princessa Roja. María Teresa de Borbón Parma, Madrid 2002, ISBN 9788427027930, p. 139

- he lived with Sixte at Rue de Varenne 47, François-Xavier de Bourbon, il fut notre roi idéal, [in:] Charles-Xavier de Bourbon, notre roi de France pour demain [insert to Lys Noir 2015], p. 11, available here

- none of the sources consulted specifies exactly whether Xavier studied in Sorbonne or in another institution

- Eusebio Ferrer Hortet, Maria Teresa Puga Garcia, 24 infantas de Espana, Madrid 2015, ISBN CDLAP00004439, p. 233. Another scholars claims that prince Xavier was "licenciado" in political and economiv sciences, José Carlos Clemente, Maria Teresa de Borbon-Parma, Joaquín Cubero Sánchez, Don Javier: una vida al servicio de la libertad, Madrid 1997, ISBN 9788401530180, p. 50, José Carlos Clemente, El carlismo contra Franco, Madrid 2003, ISBN 9788489644878, p. 96, José Carlos Clemente, Carlos Hugo de Borbón Parma: Historia de una Disidencia, Madrid 2001, ISBN 9788408040132, p. 34

- Aproximación biográfica 2002

- see e.g. an account of Don Javier taking part in the high societe life of the French capital, Le Gaulois 18.06.12, available here

- when born in 1887, Karl Habsburg could have hardly anticipated inheriting the throne; at that time he was the 5th in line. In 1889 the official heir crown prince Rudolf, son of the emperor Francis Joseph, died in unclear circumstances. Succession rights passed to Karl Ludwig, the younger brother of the emperor, who died in 1896. Succession rights passed to Karl Ludwig’s older son, archduke Franz Ferdinand. Karl Ludwig’s younger son Otto, the father of Karl, died in 1906. Franz Ferdinand, who concluded morganatic marriage in 1900 and whose would-be children were not expected to inherit the throne anyway, was killed in Sarajevo in 1914, which rendered Karl the official successor to the kaiser. When marrying Zita in 1911, Karl could have already expected inheriting the throne after his paternal uncle; however, as archduke Franz Ferdinand was of good health, Karl was not supposed to rule until the 1920s–1930s

- Manuel de Santa Cruz Alberto Ruiz de Galarreta, Apuntes y documentos para la Historia del Tradicionalismo Español, vol. 4, Madrid 1979, p. 197

- they visited Philippopoli (present-day Plovdiv), partially sight-seeing, partially gathering historical and geographical info, and partially visiting family graves, Feigl 1991, p. 111

- Feigl 1991, p. 132

- Feigl 1991, p. 131

- Antonello Biagini, Giovanna Motta (eds.), The First World War: Analysis and Interpretation, vol. 2, Cambridge 2015, ISBN 9781443886727, p. 326

- According to Prince Xavier’s personal journal, reproduced in Feigl 1991, p. 131

- The Kaiser remarked: "I can understand that they only want to do their duty", Justin C. Vovk, Imperial Requiem: Four Royal Women and the Fall of the Age of Empires, Bloomington 2014, ISBN 9781938908613, p. 283

- Vovk 2014, p. 283

- Feigl 1991, p. 156

- Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts, World War I: A Student Encyclopedia, Oxford 2005, ISBN 9781851098798, p. 1690

- Biagini, Motta 2015, p. 326

- Le Galouis 29.06.16, available here

- Josep Carles Clemente, Historia del carlismo contemporaneo, Barcelona 1977, p. 95

- Edmond Taylor, The Fall of the Dynasties: The Collapse of the Old Order: 1905–1922, New York 2015, ISBN 9781510700512, p. 359

- Jacques de Launay, Major Controversies of Contemporary History, Oxford 2014, ISBN 9781483164519, p. 69

- Vovk 2014, pp. 325–6

- Manfried Rauchensteiner, The First World War and the End of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1914–1918, Wien 2014, ISBN 9783205795889, p. 898

- Wolfdieter Bihl, La Mission de mediation des princes Sixte et Xavier de Bourbon-Parma en faveur de la paix, [in:] Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains 170 (1993), pp. 31–75

- Vovk 2014, p. 352

- Tucker, Roberts 2005, p. 1690

- Clemente 1977, p. 95

- in 1916, Le Galouis 29.06.16, available here

- Clemente 1977, p. 95

- Bogle, Bogle 1990, p. 118

- detailed discussion in J. Pelluard, La familie de Bourbon-Parma, Chambord, enjeu d’un procés de famille, [in:] Memoires de la Societe des sciences et lettres de Loir-et-Cher 37 (1982), pp. 53-61

- one scholar suggests that the marriage was the result of calculation rather than love, "más meditado con la razón que con el corazón por parte de don Javier", Heras y Borrero 2010, p. 17. In a letter from prince Xavier to his mother, he says that Madeleine "no es ninguna belleza, pero sí muy agradable. Si no ha existido por mi parte el flechado amoroso, por lo menos creo que están sentadas bien las bases del sentimiento y la razón que nor llevarán a amarnos", Spanish translation quoted after Juan Balansó, La familia rival, Barcelona 1994, ISBN 9788408012474, p. 176

- Nicolas Enache, La Descendance de Marie-Therese de Habsburg, Paris, 1996, ISBN 290800304X, pp. 416-417, 422

- Élie upheld his judgement until death. It was only once his son became head of the Bourbon-Parmas, in 1959, that the decision was reversed and the marriage of Xavier and Madeleine acknowledged as dynastic

- Chantal de Badts de Cugnac, Guy Coutant de Saisseval, Le Petit Gotha, Paris 2002, ISBN 2950797431, pp. 586-589

- Le Gaulois 22.08.28, available here

- one brother died in early infancy; two other older brothers joined the French army and were killed during the Great War

- see Chateau de Bostz, [in:] allier.auvergne service, available here Archived 10 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Badts de Cugnac, Coutant de Saisseval 2002, pp. 586-589

- the last one was born in 1940

- Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. 30/1, Seville 1979, ISBN 8474600278, p. 227

- since the 1930s prince Xavier was heavily related to Le Souvenir Vendéen, an organisation set up to protect the memory of Vendée royalists, Heras y Borrero 2010, p. 97, also Jean-Clément Martin, Le clergé vendéen face a l’industrialisation (fin XIXe – début XXe), [in:] Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l’Ouest 89/3 (1982), p. 365. He remained faithful to memory of the Vendée insurgents until his death, e.g. a 1971 commemorative volume Vendeé Sancerroise was printed with the foreword of "Son Altesse Royale le Prince Xavier de Bourbon de Parme", Heras y Borrero 2010, p. 105

- one scholar claims it is indicative that once Popular Front assumed power in France in 1936, prince Xavier sent his son Hugues, than aged 6, out of the country (to relatives living in Italy), and recalled him once Front populaire lost power, Heras y Borrero 2010, pp. 18-19

- Sixte de Bourbon, Le traité d’Utrecht et les lois fondamentales du royaume, Paris 1914, available online here

- he acknowledged Alfonso XIII as the legitimate king of Spain, Ferrer 1979, p. 72

- and demonstrated "adhesion profunda" to the legitmist claimants, opinion of the (at the time) orthodox Traditionalist author, Francisco Melgar, Don Jaime, el principe caballero, Madrid 1932, p. 227; the opinion quoted by an iconic Traditionalist historian, Ferrer 1979, pp. 72-73

- "Don Javier pasa [during 1936 talks with Alfonso Carlos] por momentos de duda y de profunda angustia. Quiere defender la Iglesia y la libertad religiosa. Pero también quiere conseguir y defender la libertad social de la que está totalmente privado el pueblo español", opinion of the scholar who re-interprets Carlism as a movement of social protest, Clemente 1977, p. 96

- Sixte’s PhD thesis was legal dissertation on the right of all the Spanish Bourbons to the French citizenship. He and Xavier felt French at heart, compare A travers le monde, [in:] Les Modes 1919, available here

- Ferrer 1979, p. 72

- Alfonso Carlos was prince Xavier’s maternal uncle - Alfonso Carlos married the sister of Xavier’s mother. Alfonso Carlos was also the brother of prince Xavier’s paternal uncle, Carlos VII, who was married to the sister of prince’s Xavier’s father

- until at least the late 1920s Alfonso Carlos was rather lukewarm towards some members of the Borbón-Parma family, especially Sixte and Xavier; this was because both brothers fought for Entente during the Great War. In the early 1920s Alfonso referred to Xavier as “un buen chico”, but excessively under influence of Sixto. He refused to receive Xavier in Vienna and preferred not to correspond with him directly. This must have changed some time until the mid-1930s, compare Ignacio Miguéliz Valcarlos (ed.), Una mirada intima al dia a dia del pretendiente carlista, Pamplona 2017, ISBN 9788423534371, pp. 213-214, 234

- Ferrer 1979, pp. 80-81, 127-129

- his older half-brother Elie recognized Alfonso XIII and demonstrated no interest in Traditionalism

- Ferrer 1979, p. 227

- Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, pp. 319-320

- according to one scholar, Don Javier engaged in conspiracy in order to prevent civil war, Clemente 1977, pp. 96-97. In the 1970s he allegedly confessed to Santiago Carillo – as referred by the latter – that had he known that the rising would lead to the civil war, he would have not engaged in the conspiracy, Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 296

- Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, pp. 214-5

- Clemente 1977, p. 24

- at one point, he asked the Navarrese Carlists conducting talks with Mola: "y, ¿a esto supeditan ustedes todo el historial y todo el futuro de la Comunión Tradicionalista, a que los Ayuntamientos de Navarra sean carlistas?", Antonio de Lizarza Iribarren, Memorias de la conspiración, [in:] Navarra fue primera, Pamplona 2006, ISBN 8493508187, p. 106

- Peñas Bernaldo 1996, pp. 21-43

- Clemente 1977, pp. 25-26, Canal 2000, pp. 324-326, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 30

- He was also assisting in procurement of arms for the Carlist volunteers; to this end Don Javier briefly travelling to Paris and Brussels. Clemente 1977, pp. 110–111

- Initially his political program was simply based on restoration of Traditionalist monarchy. As the coup turned into civil war during the later months of 1936, Don Javier hesitantly came to terms with the prospect of a transitional military dictatorship, perhaps lasting even "some years". Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain, Cambridge 1975 [re-printed with no re-edition in 2008], ISBN 9780521086349, p. 267

- Clemente 1977, pp. 113–5

- His protests were related mostly to expulsion of the Carlist political leader, Manuel Fal Conde, following launch of the Carlist military academy. Clemente 1977, p. 118; the academy initiative had been earlier pre-agreed with Don Javier, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 232

- Peñas Bernaldo 1996, pp. 241–275

- Going as far as Andalusia

- One sources claimed that Don Javier met Franco. Josep Carles Clemente Muñoz, Los días fugaces: el carlismo : de las guerras civiles a la transición democrática, Cuenca 2013, ISBN 9788495414243, p. 45. However, Don Javier’s daily diary between 17 May and 24 May 1937 does not mention any encounter with Franco. Clemente 1977, pp. 123–124

- See Don Javier’s journal, reproduced in Clemente 1977, pp. 123–4. The same author once claimed that Don Javier was expelled on 17 May, see Clemente 1977, p. 31, and once that he entered Spain on 17 May. Clemente 2013, p. 44. From his journal it seems that he entered Spain on 17 May and left on 25 May

- According to one author, Don Javier re-entered Spain in late November 1937 and left between Christmas and the end of 1937. Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldía carlista. Memoria de una represión silenciada, Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711, p. 74, similar opinion in Manuel Martorell Pérez, Carlos Hugo frente a Juan Carlos. La solución federal para España que Franco rechazó, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788477682653, p. 13. Some sources point to November, see Aproximación biográfica 2002, Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965–1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015, p. 479

- Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 371–2

- according to a recent work, Don Javier had two interviews with Franco; one in early December 1937 and another on Christmas Day the same year. Reportedly, Franco very politely insisted that the regent leave Spain, as his presence allegedly caused problems with the Germans and Italians. Miralles Climent 2018, p. 74. Other works provide confusing opinions. One scholar claims vaguely that "Don Javier se intrevista en Burgos con Franco" but gives no date, seeming to refer to the spring of 1937, though given poor credibility of the author this statement should be taken cautiously, see Clemente 1977, p. 98. Another scholar claims Don Javier met Franco in December 1937, see Manuel Martorell Pérez, Carlos Hugo frente a Juan Carlos. La solución federal para España que Franco rechazó, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788477682653, p. 13. Another scholar claims the two met sometime in 1937 in Seville and provides a number of details, but no source. Franco reportedly advised the prince that many generals of republican mindset who had joined the coup were unhappy about Don Javier's presence. He also suggested that Don Javier might do more good for the Nationalist cause from abroad. Don Javier agreed to leave, but refused to associate with the Paris link suggested, claiming the person recommended SS operative, Apuntes y documentos para la Historia del Tradicionalismo Español, vol. 1, Madrid 1979, pp. 157–158

- Spanish Carlists were careful to emphasise that Don Javier's enlistment in the Belgian army in no way changed the Carlists' neutral position toward the warring parties of the Second World War. Compare, e.g., the meeting of Carlist executive Manuel de Santa Cruz [Alberto Ruiz de Galarreta], Apuntes y documentos para la Historia del Tradicionalismo Español, vol. 2, Madrid 1979, p. 26

- De Besson a Dachau, [in:] randos.allier service, available here

- Bourbon Parme Xavier de, [in:] Amis de la Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Déportation de l'Allier service, available here

- Somerset Daily American 08.08.45, available here

- François-Xavier deBourbon, il fut notre roi idéal 2015, p. 11, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 260

- Bostz was only 12 km away from Moulins, one of the major demarcation line crossing points, see Moulins en 1939–1945, [in:] Anonymes, Justes et persécutés durant la période nazie service, available here

- Marcel Lerecouvreux, Les accords Halifax-Chevalier, [in:] Marcel Lerecouvreux, Résurrection de l'Armée française, de Weygand à Giraud, Paris 1955, pp. 109–110

- Unlike most Carlists, who considered Britain a hotbed of liberalism, plutocracy, freemasonry and greed, apart from being Spain's historical arch-enemy, Don Javier was "essentially Anglophile". In late stages of the civil war he spoke with a British Foreign Office representative expressing his sharp disagreement with Franco's pro-German course, only to be dismissed as the head of "medieval reactionaries", Javier Tusell, Franco en la guerra civil, Barcelona 1992, ISBN 9788472236486, pp. 359–360, referred after Stanley G. Payne, El Carlismo en la politica espanola, [in:] Stanley G. Payne (ed.), Identidad y nacionalismo an la España contemporanea: el carlismo, 1833–1975, Madrid 2002, ISBN 8487863469, p. 121

- J. L., Prince Xavier de Bourbon, Les accords secrets franco-anglais de decembre 1940 [review], [in:] Politique etrangere 15/2 (1950), pp. 240–242

- see e.g. Gaston Schmitt, Les accords secrets franco-britanniques de novembre-décembre 1940. Histoire de ou Mystification, Paris 1957, and its review by Henri Bernard, [in:] Revue belge de philologie et d’histoire 36/3 (1958), pp. 1017–1024

- Manuel de Santa Cruz [Alberto Ruiz de Galarreta], Apuntes y documentos para la Historia del Tradicionalismo Español, vol. 1, Madrid 1979, pp. 163–179

- "desorganización y desorientación. La pasividad y el retraimiento de las bases eran la norma", Canal 2000, pp. 349–350

- Dorotheum. Scholls-aktion im Schloss Puchheim, Salzburg 2002, p. 2, available here

- in his memoirs Don Javier claims he entered into contact with the Resistance "during the second year of the war", which might point to any time between 1940 and 1942, according to Josep Carles Clemente, Raros, Heterodoxos, Disidentes y Viñetas Del Carlismo, Barcelona 1995, ISBN 9788424507077, p. 111

- François-Xavier deBourbon, il fut notre roi idéal 2015, p. 11

- because of lack of petrol, François-Xavier de Bourbon, il fut notre roi idéal 2015, p. 11; another source claims he repeatedly travelled to Vichy to get the detainees freed on many instances, Clemente 1995, p. 110

- claiming that one of the detained was his nephew

- Even some generally high-quality works claim wrongly that he was arrested in 1943, see e.g. Canal 2000, p. 349

- François-Xavier de Bourbon, il fut notre roi idéal 2015, p. 11

- Ignacio Romero Raizábal, El prisionero de Dachau 156.270, Santander 1972 reports 156270 as Bourbon-Parma's prisoner number at Dachau; the Arolsen Archives preserve a prisoner registry card on his name with number 101057. See Bourbon Parme Xavier de, [in:] Amis de la Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Déportation de l'Allier service. Some authors claim that during railway transport to Dachau the train was bombed and all documentation was lost in ensuing fire, which rendered all prisoners – including Don Javier – totally anonymous, Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldia carlista, Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711, p. 236

- Franco allegedly declared that he did not know "this gentleman of French nationality" and that the Germans were free to do whatever they wished, Clemente 1996, p. 53

- François-Xavier de Bourbon, il fut notre roi idéal 2015, p. 11. According to his own account, Don Javier assisted other prisoners, e.g. by providing Christian consolation, see Ignacio Romero Raizabal, El prisionero de Dachau 156.270, Santander 1972, e.g. pp. 14–15. His account should be treated with caution, as some information does not necessarily add up, e.g. he claims to have met a colleague from Stella Matutina, a certain "Knialosenki", a Pole who served as head of General Staff of the Polish army. The heads of staff who fell into German hands, Piskor and Gąsiorowski, are not known to have been detained in Dachau

- Some sources claim Don Javier was liberated in May. García Riol 2015, p. 480. Another source claims he was transferred from Dachau to Psax because the Nazis intended to use him a hostage in bargaining with the Allies, but that he was spared thanks to clashes between the Gestapo and the Wehrmacht. Clemente 1995, p. 111. Yet another author claims that at some time Don Javier was transferred from Dachau to a Tyrolian location at Proger-Wildsee, where in May 1945 he was reportedly liberated by the Allies. Miralles Climent 2018, p. 236

- or according to other sources 35 kg, Clemente 1996, p. 53

- François-Xavier de Bourbon, il fut notre roi idéal 2015, p. 11

- Don Javier crossed the border Bidasoa river led by local Basque smugglers. When asked whether they knew who their customer was, one of them answered plainly "gure errege", our king. Which did not prevent them from asking 6,000 ptas for the service, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 319

- full title La única solución (Llamamiento de la Comunión Tradicionalista con la concreción práctica de sus principios. Con ocasión de la presión internacional y el cerco de la ONU. Inminente Ley de Sucesión); the document protested also international ostracism towards Spain, Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 321-2, 374

- according to the document, "el régimen de Caudillaje" does not have "ni caracteres de estabilidad ni raiz española, por ser un régimen de poder personal, inconciliable con los derechos de la persona humana y de las entidades infrasoberanas en que aquella se desenvuelve"; according to some scholars, the document marked – following previous years of ambiguity – definitive breach with the regime, Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 171-172

- the two groups in question were supporters of Carlos VIII, the so-called carloctavistas, and supporters of Don Juan, the so-called juanistas (or carlo-juanistas)

- compare Don Javier’s 1947 letter read at Montserrat, Clemente 1977, pp. 292-4

- in 1948 upon the wedding of his niece Anne Bourbon-Parma to Michael I of Romania, Xaview forbade the bride's parents from attending the wedding, Marlene Eilers-Koenig, The Marriage of King Michael and Queen Anne of Romania, [in:] European Royal History Journal LXIII (2008), pp. 3–10

- César Alcalá, D. Mauricio de Sivatte. Una biografía política (1901-1980), Barcelona 2001, ISBN 8493109797, pp. 43, 59-62, 67, 71-72, Robert Vallverdú i Martí, La metamorfosi del carlisme català: del "Déu, Pàtria i Rei" a l'Assamblea de Catalunya (1936-1975), Barcelona 2014, ISBN 9788498837261, esp. the chapter L’enfrontament Sivatte – Fal Conde, pp. 106-111

- in fact, Don Javier protested to Franco over the Ley, Jeremy MacClancy, The Decline of Carlism, Reno 2000, ISBN 9780874173444, p. 85, Heras y Borrero 2010, p. 39

- Sivatte claimed that even voting "no" in the referendum was improper; the only correct path was to ignore all Francoist referendums, Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962–1977, Pamplona 1997; ISBN 9788431315641, p. 27, Alcalá 2001, pp. 74-80

- already in 1945 the first signs of dissent started to appear, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 299

- especially that at the turn of the decades international pressure eased, the Francoist regime seemed consolidated and speculations about Franco’s imminent removal faded away, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 328

- in 1949; some authors claim that Sivatte was expelled from Comunión Tradicionalista, Canal 2000, p. 354, some claim that he left himself, Alcalá 2001, p. 94. Another author claims that Sivatte was expelled as late as 1956, Mercedes Vázquez de Prada Tiffe, El nuevo rumbo político del carlismo hacia la colaboración con el régimen (1955-56), [in:] Hispania 69 (2009), p. 195

- Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 326

- the one that the Carlists set their eyes on was Iformaciones, to be actually taken over by the Carlists later

- Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 328-331, Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, pp. 74- 75

- calls for Don Javier to assume the claim were usually based on presumed agreement among the Carlists, vaguely corresponding to decision of grand Carlist gathering as specified by Alfonso Carlos, and not on previously applied Carlist heritage rules of succession. In terms of these, Don Javier’s right to the throne was highly disputed. His claim could have been advanced only if excluding – for a number of reasons, ranging from morganatic marriages to embracing Liberalism – 5 older branches, namely those of Ferdinand of Borbón-Dos Sicilias, Infante Gabriel, Francisco de Paula, Carlota Joaquina and doña Blanca

- MacClancy 2000, p. 83, Heras y Borrero 2010, p. 41. In Guernica Don Javier pledged to defend Basque fueros, Aproximación biográfica 2002

- news of the Carlist king arriving leaked out, prompting crowds to welcome their monarch to embarrassment of both Don Javier and Fal Conde, Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 338–39

-

- the manifesto is quoted here, letter to son in Clemente 1977, pp. 296-7

- Don Javier avoided direct language and stated literally that "he resuelto asumir la realeza de las Coronas de España en sucesión del último Rey", quoted after Canal 2000, p. 354. Though Fal for 15 years opposed terminating the regency, in 1952 it was he who convinced Don Javier to declare himself king; one scholar considers Acto de Barcelona "l’obra mestra de Fal, [which] avivá el carlisme i aillá la Comunió del perill contaminant del joanisme i del franquisme", Vallverdú 2014, p. 144

- Alcalá 2001, p. 101

- Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 339–40, Ana Marín Fidaldo, Manuel M. Burgueño, In memoriam. Manuel J. Fal Conde (1894-1975), Sevilla 1980, pp. 51–52

- compare a document titled La Posición Política de la Comunión Tradicionalista of 1954, available online here

- e.g. at gatherings of various European royals

- in 1955, when meeting Don Juan at one of the royal weddings, Alcalá 2001, p. 102

- Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 392, see also Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957-1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407, pp. 31-47

- MacClancy 2000, pp. 85-88

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 33

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 33, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 393. Fal’s resignation was in fact suggested by Don Javier. It came as a surprise, since earlier that year Fal staged many warm meetings with the royal family, e.g. in Seville, Lourdes and San Sebastián, Marín, Burgueño 1980, p. 53., the version difficult to reconcile with later continuously cordial relations between Fal and his king

- MacClancy 2000, p. 87

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 35

- Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 36