Princess Clémentine of Belgium

Princess Clémentine of Belgium (French: Clémentine Albertine Marie Léopoldine, Dutch: Clementina Albertina Maria Leopoldina; 30 July 1872 – 8 March 1955), was by birth a Princess of Belgium and member of the House of Wettin in the branch of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (as such she was also styled Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Duchess in Saxony). In 1910, she became Princess Napoléon and de jure Empress consort of the French as the wife of Napoléon Victor Jérôme Frédéric Bonaparte, Bonapartist pretender to the Imperial throne of France (as Napoleon V).

| Clémentine of Belgium | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princess Napoléon | |||||

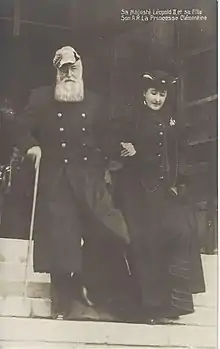

Princess Clementine, ca. 1895. | |||||

| Born | 30 July 1872 Palace of Laeken, Laeken, Brussels, Belgium | ||||

| Died | 8 March 1955 (aged 82) Clair-Vallon Villa, Cimiez, Nice, French Fourth Republic | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Princess Marie Clotilde Bonaparte Louis, Prince Napoléon | ||||

| |||||

| House | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | ||||

| Father | Leopold II of Belgium | ||||

| Mother | Archduchess Marie Henriette of Austria | ||||

The third daughter of King Leopold II of Belgium and Queen Marie Henriette (born Archduchess of Austria), her birth was the result of a final reconciliation of her parents after the death in 1869 of their son and only dynastic heir, Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant. As a teenager, Clémentine fell in love with her first cousin Prince Baudouin. The young man, who did not share the feelings his cousin had for him, died of pneumonia in 1891 at the age of 21.

Clémentine hardly got along with her mother and was closer to her father, whom she frequently accompanied. He hoped in 1896 that she would marry Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, but Clémentine opposed the union.

As years went by, Clémentine remained single. Around 1902, shortly after Queen Marie Henriette's death, she began to have feelings for Prince Napoléon Victor Bonaparte. Despite the support of the Italian royal family, King Leopold II to avoid incurring the wrath of the Third French Republic, refused any marriage between his daughter and the Bonapartist pretender.

Clémentine had to wait for her father's death in 1909 to be able to marry Prince Napoleon. Their marriage finally took place in 1910, after the new Belgian ruler, her cousin King Albert I, gave his consent. The couple moved to Avenue Louise in Brussels. The couple had two children: Marie Clotilde, born in 1912, and Louis Jérôme, born in 1914.

When World War I broke out, Clémentine and her family took refuge in Great Britain and were hosted in the residence of the former Empress Eugénie. Across the Channel, Clémentine was active for the Belgian cause, and many compatriots found refuge in England. With her cousin-in-law Elisabeth of Bavaria, Queen of Belgium, she worked actively for the Red Cross.

After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, Clémentine returned to Belgium. In her Château de Ronchinne, in the Namur Province, she and her husband devoted themselves to charitable activities after four years of war. Clémentine frequently visited Turin and Rome with the Italian royal family.

She was somewhat removed from French political life, but Clémentine convinced her husband to return to politics and supported him financially. However, he gradually rallied to the republican idea. In 1926, he died a week after being subjected to a stroke. Clémentine brought up her two barely adolescent children and was keen to preserve the Bonapartist movement of which she became the “regent” until her son came of age in 1935, but she had no influence on French political reality.

From 1937, Clémentine stayed more and more frequently in France, but it was in Ronchinne that she was surprised by the declaration of World War II in September 1939. As soon as she could, she went to France and stayed there since the invasion of Belgium in the spring of 1940 prevented her from returning to her native country. After 1945, Clémentine somewhat abandoned her property in Ronchinne and divided her time between Savoy and the Côte d'Azur, where she died in 1955, at the age of 82.

Life

Early years

Third daughter of King Leopold II of Belgium and Queen Marie Henriette, Clémentine Albertine Marie Léopoldine of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was born at the Palace of Laeken on 30 July 1872, at 6 p.m., three years after the accidental death of her older brother Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant, the King's sole direct heir. The latter nourished the hope of having a second son and had therefore resumed an intimate life with the Queen; but, after a miscarriage in March 1871,[1] another girl is born: Clémentine, the royal couple's last child.[2][3] She was baptized on 3 September 1872 at the Palace of Laeken during a short ceremony, followed by a gala lunch attended by around 80 guests.[4] Her first name pays homage to her godmother and great-aunt, Princess Clémentine of Orléans, while her middle name refers to that of her godfather, Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen, a cousin of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria.[5]

The royal couple already had two daughters, Louise and Stéphanie, aged 14 and 8 respectively, so the birth of a new daughter deeply disappointed the King. The coldness that had settled between Leopold II and Marie Henriette reflected on their relationship with their youngest daughter, and the Queen, above all, was particularly distant and bitter.[6][7] She nicknamed Clémentine Reuske ("the little giant") because of her large size. Like her sisters, Clémentine received lessons in French, German, music, history and literature.[6] A zealous student, Clémentine showed a predilection for history and literature, while her mother took care to instill in her a careful musical training thanks to the lessons of the pianist and composer Auguste Dupont.[8]

Louise, the princess' older sister, married in 1875 with a cousin, Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and settled in Vienna. Before her prestigious marriage to Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, in 1881, Stéphanie played a maternal role with her younger sister, somewhat neglected by her mother.[9] From the age of 8, Clémentine was the only child of the Belgian royal couple to stay in Belgium and spent a sad and lonely childhood at the Palace de Laeken. Even though she sees her cousins Henriette and Joséphine Caroline weekly, her universe was essentially limited to adults, including her governess Omérine Drancourt.[8] According to her biographer, Dominique Paoli, "the unbalanced Queen gives the impression of a mother led by her mood. [She] makes Laeken's atmosphere unbreathable. Jealousy often guides her [...] She is angry with the whole world for her misfortunes, and, of course, Clémentine sometimes pays the price for it".[8]

Very pious, Clémentine was authorized by her parents to frequent Madame Cléry, the superior of the Collège du Sacré-Cœur de Jette, not far from Laeken. There she rubbed shoulders, for a few hours on Thursday and Sunday, with other aristocrats, such as Marguerite de Limburg-Stirum and Nathalie de Croÿ. In April 1889, two months after the death of her brother-in-law Rudolf in strange circumstances in Mayerling, Clémentine and her mother stayed with Stéphanie, now widowed, at the Miramare Castle. The two sisters strengthened their bond and happily played music together. It was also in the spring of this year that Clémentine discovered the charms of Venice.

In December 1889, her studies were officially over, but she still took some classes in religion, English and German.[10] Her governess was replaced by a maid of honor, an aristocrat and pianist in her spare time, Zoé d'Oldeneel, while her parents allocated her a living room where she could receive guests. However, Clementine's joy was clouded by drama: On 1 January 1890, while Clémentine was alone in Laeken with Omérine Drancourt and her maid Toni, Clémentine settled in the rooms of her mother, who was absent to attend the New Year's celebrations with the King, and played the piano. Toni shouted to Clémentine to come down before warning Omérine Drancourt to run away because a fire had broken out in the Palace. Omérine Drancourt began to pray, before trying to take personal items. They could not find Omérine, whom Clémentine wanted a servant to look for, because a thick smoke prevented any rescue.[11] Clémentine was reduced to assist helplessly, from the lawn of the Palace, to the intervention of the firefighters who ended up discovering Omérine Drancourt's lifeless body.[12]

In 1890, as Clémentine approached her eighteenth birthday, she learned to drive carriages: Guided by her mother, she trained to lead station wagons. She succeeded very well and considered this hobby amusing. She showed a predilection for the equestrian world and was able to identify the different breeds of horses she met. In summer, she attended horse shows in Brussels, one of her favorite distractions with the amenities provided by the park of the Palace of Laeken where she liked to have lunch on the grass and sometimes even load haystacks. In July, she accompanied her parents to Ostend.[13] When she turned 18, Clémentine was with her mother in Spa. The Queen took her and three of her retinue on a donkey ride through the city. They were followed by an army of curious people, astonished to see them ride these "little noble steeds".[14]

First loves and more independence

-nb-crop.jpg.webp)

As a teenager, Clémentine fell in love with her cousin Prince Baudouin, considered the future heir to the throne.[15][16] The young man, who did not share the feelings that his cousin had for him and did not like the atmosphere that reigned at his uncle's house in Laeken, was supported in his refusal by his parents, accentuating the cooling of relations between Leopold II and his brother the Count of Flanders, father of the intended groom. The latter found his niece a "beautiful lady, but too tall and affected";[15] he was also critical to the girl, whom in private he called "the big Clémentine". [17] All hope vanished when Prince Baudouin died of pneumonia on 23 January 1891 at the age of 21. The princess drew on faith the courage to overcome the death of her cousin and first love.[15]

.jpg.webp)

Queen Marie Henriette increasingly fled the Belgian court to take refuge in Spa where she acquired a villa in 1894; in her mother's absence, Clémentine fulfilled the functions of "first lady" alongside King Leopold II,[18][19] who protected her from her mother's embittered character and granted her an independence that few unmarried princesses could enjoy at that time. To her sister Stéphanie, Clémentine wrote, "I have a very nice situation, I have my small property, my horses; I got from papa not to go to Spa anymore, because I can't anymore, so that in the summer I will be free".[18]

The property to which she referred was the Belvédère Castle, built on the domain of Laeken. Clémentine also knew what Dominique Paoli calls a "loving friendship" with Baron Auguste Goffinet, secretary and confidant of Leopold II. However, the nature of the relationship with the Baron, who was almost 15 years older than her and not of royal blood, remained platonic.[20]

In the autumn of 1896, a more plausible party appeared as a suitor for her hand, Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, but the princess refused this union because she confided to her father that she did not like the candidate and that, in her life, the unknown scared her. In spite of her father's insistence, who judged Rupprecht favorably and considered him an advantageous political choice for Belgium, Clémentine maintained her refusal to marry the Bavarian suitor and Leopold II finally relented.[21][22]

Family affairs

While Clémentine had acquired a certain freedom, her older sisters were gradually ostracized from the Belgian royal family. In 1895, the eldest, Louise, fell under the spell of a Croatian officer, Geza Mattachich (Croatian: Gejza Matačić), with whom she had an adulterous relationship known throughout Europe. King Leopold II and Queen Marie Henriette forbade Stéphanie to see her sister Louise, who was no longer received in Belgium. In 1898, Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Louise's scorned husband, provoked his rival into a duel. He then had to settle large debts contracted by Louise, but he failed to meet the demands of the many creditors.[23] Prince Philip and Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria were determined to bring Louise back to Austria and keep her away from Mattachich. Supported in his designs by the Belgian sovereigns, Prince Philip then had his wife declared insane and convinced the Austrian Emperor to have her locked up in a psychiatric hospital. She remained interned there until 1904 [24] before they finally divorced in 1906.[25]

Stéphanie was also already distant from her parents, who did not wish to visit her because of her proximity to the scandals affecting Louise. However, the King had authorized Clémentine to see her sister again in April 1898 because she was recovering from severe pneumonia. Leopold II had even escorted Clémentine in the Dolomites, so that she stayed with Stéphanie, convalescing.[26] However, when Stéphanie remarried in 1900, against her parents' advice, to Count Elemér Lónyay de Nagy-Lónya et Vásáros-Namény, a Hungarian nobleman of lower rank, the Belgian sovereigns, offended that Stéphanie had not trusted them with her matrimonial projects, severed any relationship with their daughter, whom they also forbade to return to Belgium.[27]

Stay in Saint-Raphaël and broken engagement

During the winter of 1899-1900, due to her bronchial pathologies, Clémentine spent a few months, on the advice of her doctors, in Saint-Raphaël, on the Var coast. The isolation was complete there and for the first time in her life, the princess found herself without any member of her family. She devoted herself to photography, thanks to a camera offered to her by her aunt, the Countess of Flanders.[28] In March 1900 however, her stay was interrupted by an illness of the Queen who only saw her for a few minutes each day at Spa. On the other hand, Marie Henriette claimed her dogs, causing the return of Clémentine, wounded by the little maternal attitude of the Queen, from the south of France.[29]

From time to time, Clémentine received invitations from royalty. She was invited by Queen Victoria (who was also staying on the Côte d'Azur) and to Cannes by the Count and Countess of Caserta (heads of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies), where, at the instigation of her sister Stéphanie, she met Prince Carlos of Bourbon-Two Sicilies (nicknamed "Nino"), second son of the Count and Countess. Clémentine seemed favorably impressed by the young man, two years her senior: "Nino is very good, very handsome. I believe him to be serious, straightforward, honest. It is highly praised. He is very pious and has all the qualities required, it seems to me, to make a woman happy".[28] The press mentioned an engagement, and Clémentine believed she had to break it because she was no longer under the spell of the Prince, who nevertheless found her to his liking.[30]

Clémentine, still single, returned to Belgium, after a stay in Balmoral Castle with Queen Victoria. In the summer of 1900, she stayed in Ostend before finding herself alone again in Laeken because the King refused to allow Clémentine to join Stéphanie while staying in the Netherlands. On the other hand, Leopold II went alone to see Stéphanie and claimed that Clémentine was unwell. An intense scene followed between the King and Clémentine who, from then on, violated her father's orders to communicate by letter with Stéphanie. Leopold II threatened, if he learned that she was corresponding with her elder sister, to "throw her into the street".[31]

Death of Queen Marie Henriette

The Queen's health suddenly declined starting in June 1902.[32] During this period, King Leopold II was in France, while Clémentine remained at the Palace of Laeken. The absence of her younger daughter was probably due to the disagreement between Marie Henriette and Clémentine, who had always shown a certain preference for her father.[32] However, Marie Henriette could count on the dedication of Baron Auguste Goffinet. She died on 19 September 1902 at her villa in Spa. The day after her death, Leopold II returned from Bagnères-de-Luchon where he was on vacation with his last mistress, Blanche dit Caroline Lacroix, the "Baroness of Vaughan". When he arrived in Spa, the King found his daughter Clémentine there; but learning that Stéphanie is also present and praying in front of her mother's remains, he refused to meet her. Stéphanie was forced to leave Spa and went to Brussels where she was acclaimed by the people who supported her.[33][34] Louise, the eldest of the late Queen's daughters, being interned, did not go to Belgium.[33]

Clementine's choice

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Clémentine had feelings for Prince Napoleon Victor Bonaparte (known by his middle name Victor), ten years her senior and head of the Imperial House of Bonaparte, whom she had known since the 1880s.[35][36] Prince Victor Napoléon was the son of Prince Napoléon-Jérôme Bonaparte and Princess Maria Clotilde of Savoy; through his maternal lineage, Victor was related to King Umberto I of Italy and with almost all of the Almanach de Gotha.[35][37] It was in February 1904, that Victor, in agreement with Clémentine, sent his cousin the Duke of Aosta to Leopold II to ask for his youngest daughter's hand. The sovereign remained intractable and refused this marriage project: He did not want this union, so as not to compromise relations between Belgium and the Third French Republic.[35][38] On the other hand, Victor had had an affair for more than 15 years with Marie Biot,[lower-alpha 1] a ballerina who followed him from Paris when he moved to Brussels in 1889 and with whom he had two sons.[40]

Victor Napoleon was settled at a mansion located in N°239 of Avenue Louise in Brussels.[41] He benefited from the subsidies granted by Empress Eugenie and the Bonapartist circles which enabled him to lead at great speed. He considered it his duty to perpetuate the cult that had been dedicated to Napoleon I: "The worship of the memory of Napoleon is my only consolation to me who pays exile glory to bear his name and perilous honor to be called upon to take on the heavy burden of his legacy".[42] In Belgium, Victor wanted to remain discreet and traveled, since the beginning of the 1890s, a lot in Europe where he was favorably received by several sovereigns, including Tsar Alexander III of Russia. This advantageous position did not, however, influence the King of the Belgians, who still considered him above all as an opponent of the French government.[43] In addition, Leopold II did not forget that the Emperor Napoleon III once aspired to conquer Belgium,[44] nor that he was the one who caused the misfortune of his beloved sister Charlotte by inciting her husband Archduke Maximilian of Austria to reign in Mexico, before abandoning them to their fate.[43][45]

Leopold II maintains his refusal

After the refusal of her suitor, Clémentine decided to confront her father directly. At 31, she considered that she had sacrificed herself so far and insisted respectfully, then firmly with her father,[46][47] who retorted: "My duty, four hours from Paris, is to live on good terms with the French Republic".[46] A terrible scene ensued. Shortly after, a ball was held at the court. The King spoke at length with his sister-in-law, the Countess of Flanders, who had already received Victor in a friendly manner in her Palace in the Rue de la Régence. However, the Countess was also opposed to her niece's marriage to a Bonaparte.[48][49] Leopold II, on the other hand, declared himself ready to do anything for his daughter if she wished another union. He was willing to make her life easier, but he feared that Clémentine would go against his wishes. The Countess of Flanders comforted her brother-in-law by affirming that Victor would never dare go against the king and added that she doubted the strength of the feelings between Clémentine and Victor, who had never seen each other for more than five minutes face to face. In the fall of 1904, Clémentine was still single and was now at odds with her father.[48]

In the spring of 1905, the Belgian press took up the question and published several articles about a possible marriage of Clémentine. Le Peuple, the official organ of the Belgian Labour Party (POB), published:

Reason of State is invoked against the marriage of Princess Clémentine to Prince Victor Napoleon, as if a woman does not have the right to dispose of her heart as she understands [...] As if it were not for her to judge for herself whether the descendant of King Jérôme suited her as a husband [...].[50]

On this same subject, the Patriote lectured L'Étoile belge and thus asked the question:

One would understand that a Belgian newspaper echoed many Brussels residents, respectfully attached to the princess and said to her: Princess, think about it! A woman who is thinking of becoming the legal wife of a man who has lived twenty years with another woman, still alive and who has three [sic] children, can she promise himself lasting happiness?, but invoke a war between Belgium and France, in connection with this princely novel is childishness and pure phantasmagoria.[50]

Le Peuple also claimed:

Prince Victor owes to the King [of the Belgians] and to the government to be able to direct from our territory his imperialist propaganda against the neighboring and friendly Republic, while being on the best terms with the Minister of France in Brussels, the nationalist and clerical Gérard.[51]

Death of King Leopold II

From 1905, Clémentine settled down permanently at Belvédère Castle,[52][53] and sometimes also lived in her late mother's villa in Spa. To distract herself, she paid a few visits to the painter Edwin Ganz (specialist in the representation of horses and an artist close to the Belgian royal family,[54] in particular to Clémentine[55]), who was lodged by her aunt Empress Charlotte of Mexico in her Bouchout Castle. She made one or two visits at Balmoral, with King Edward VII. In 1907, a certain harmony was reborn between Clémentine and her father. She sometimes joined him at his property in the south of France.[52] In the fall of 1909, Leopold II was subject to an intestinal obstruction and had to be operated on. The outcome of the surgery was fatal: the King died of an embolism on 17 December 1909. Clémentine was deeply affected because she had, despite their differences, managed to maintain a special relationship with her father.[52][56]

A marriage for inclination

At the death of her father, Clémentine's cousin King Albert I [57]gave his consent and agreed to her marriage with the Prince Napoleon.[58] Clémentine, after a stay with her sister Stéphanie in Hungary, met under the auspices of the Italian royal family in June 1910 at Turin; three months later, in September, the official betrothal between Clémentine and Victor was celebrated.[59][60] The wedding took place on 14 November 1910 at the Castle of Moncalieri, one of the residences of the Italian royal family, where Princess Maria Clotilde, mother of the groom, resided. In Italy, there is no legal provision prescribing the completion of civil marriage before religious marriage. However, the groom, who recalled that Napoleon I had instituted civil marriage in modern legislation, insisted that the civil ceremony preceded the religious blessing.[59] Both ceremonies were relatively intimate: Apart from the members of the House of Savoy and the Bonapartes, no other European royal family was present.[61] The Countess of Flanders, the sole representative of the Belgian royal family, accompanied Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, divorced husband of the absent Princess Louise. Clémentine was delighted with the ceremony and the kindness of her relatives, and especially of her mother-in-law, Princess Maria Clotilde, who was very considerate towards her.[62][63]

The honeymoon trip lasted a month and took the new couple, celebrated everywhere, to Rome , Vienna, Hungary and Bohemia. At the Quirinal Palace, King Victor Emmanuel III gave a long series of lunches and dinners in their honor. The reception of the Habsburgs in Vienna was just as sumptuous. The celebrations ended at Rusovce Mansion, home of Clémentine's sister Stéphanie. Finally, the couple moved to Avenue Louise in Brussels.[64] To accommodate his wife, Prince Victor expanded his residence by acquiring the N° 241. Clementine judged the housing "narrow, wet [and] poor".[41] However, she adapted to her new residence, which she described as a "historical reliquary",[65] and where she only had two chambermaids. Striving to fill in her intellectual gaps, she cultivated herself in order, she said, to equal her husband: "I try to read a lot to reach the height, and it is a job".[66][67]

Eager to become parents as quick as possible,[68] the Prince and Princess Napoleon had two children:

- Princess Marie-Clotilde Bonaparte (20 March 1912 – 14 April 1996), married on 17 October 1938 to Count Serge de Witt, with whom she had ten children, of which eight reached adulthood. One of her granddaughters, Laetitia de Witt, became a historian, and wrote a biography of her great-grandfather Victor, Le Prince Victor Napoléon, where her great-grandmother Clémentine was also extensively mentioned.

- Prince Louis Jérôme Bonaparte (23 January 1914 – 3 May 1997), who succeeded his father in 1926 as the Bonapartist pretender to the Imperial throne of France (under the name of Napoleon VI); married on 16 August 1949 to Alix de Foresta, with whom he had four children.

In the spring of 1912, shortly after the birth of Marie-Clotilde, Clémentine and Victor occupied the property they had acquired in Ronchinne, in the Namur Province, a castle which commanded an area of 233 hectares and where work was needed. While Victor acquired antique furniture and called on François Malfait, the architect of the city of Brussels, to give the building an architectural Mosan style,[69][70] Clémentine had the stables and the garden fitted out, as well as the creation of a model farm and the erection of a chapel.[71] Victor was discreet and when he commented on a French political event, he addressed journalists from London. The Belgians and their King were grateful to him, just as they appreciated that Clémentine distanced herself from her sisters during the lawsuits they had brought against the Belgian State in the context of the succession of their father Leopold II.[72][73] The Belgian sovereigns maintained cordial relations with the Prince and Princess Napoleon, whom they gladly invited in private or during official ceremonies.[74]

World War I

This peaceful existence was suddenly darkened by the World War I. In August 1914, events precipitated: Prince Victor Napoleon was prevented by the French State from enlisting in the army, while King Albert I was forced to fall back on Antwerp, soon bombarded by the Germans.[75][76] Clémentine and her husband hesitated before agreeing to take refuge in Great Britain with Empress Eugenie, widow of Napoleon III, who had invited them to join her at her residence in Farnborough Hill, 40 km south from London.[75][77] Their cohabitation lasted throughout the conflict. Clémentine adapted quite easily, but she was always afraid of an argument with her "whimsical and original" great-aunt.[75][78]

One of the wings of the English residence iwa transformed into a care center, while Clémentine worked in favor of her many Belgian compatriots who had found refuge across the Channel. The Belgian press regularly echoed her activities, stressing that "in this eminently French environment, to which Princess Clémentine brings the Belgian note, we do not forget the recognition due to our noble Allies".[79] She patronized many patriotic associations and attended meetings of Belgian war invalids, the League of Belgian Patriots, the Belgian soldier's clothing work, and many other organizations intended to raise funds. The events of these associations sometimes consisted of concerts, theatrical mornings, and exhibitions. She had contacts with the British royal family, with Paul Hymans (Minister Plenipotentiary in London), and with artists such as the painter James Ensor, the sculptor Victor Rousseau and the musicians Eugène Ysaÿe and Camille Saint-Saëns.[80]

Throughout the war, Clémentine received visits from her cousin-in-law Queen Elizabeth, who sheltered her children in Great Britain. Élisabeth was reassured to know Clémentine was present. Together, Clémentine and Élisabeth worked for the Red Cross. Clémentine's children, for their part, continued to live with their parents. Their education was quite severe, but it was tempered by real affection. Victor sometimes joined Clémentine in presiding over ceremonies under the joint patronage of the King of the Belgians and President Poincaré.[81] After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, Victor and Clémentine waited a few more months before returning to Belgium, where their property in Ronchinne had suffered somewhat during the four years of war.[82][83]

Involvement in the Bonapartist movement

Affected by the poor results of the Bonapartists in the 1910 French legislative election, Prince Victor moved away from French political life and it was only under the leadership of Clémentine that he returned to it later.[84] In fact, since their marriage, Clémentine had partly financed the movement's electoral campaign.[85] However, Victor vigorously opposed his wife's involvement in politics. Despite the requests of several Bonapartist personalities, the Prince thus refused that his wife be used as an instrument of propaganda.[86] Not being affected by the law of exile, Clémentine nonetheless represented her husband at official ceremonies and commemorations attached to the Napoleonic legacy.[87] She also corresponded with several Bonapartist personalities.[88]

After World War I, Prince Victor lost all illusion of an Imperial restoration and gradually rallied to the Republican idea. This was not the case with Clémentine, who wished to preserve the heritage of their son.[89] After the bitter failure of the Bonapartists in the 1924 French legislative election and Victor's final estrangement from political life, it was Clémentine who entrusted the reorganization of the party to Jean Régnier, Duc de Massa.[90] After the death of her husband in 1926, Clémentine became the "Regent" for the Bonapartist movement until the coming of age of Prince Louis, fixed at his 21st birthday. Despite its goodwill, the movement continued to falter. According to historian Laetitia de Witt, Clémentine's great-granddaughter: "Without a leader and following the inclination of the Princess, the Bonapartists are detached from political reality. The few gatherings take on the appearance of meetings of the Napoleonic elite".[91]

Post-war

In the spring of 1919, Clémentine and her family returned to Belgium. In Ronchinne, she devoted part of her time to charitable works. In May 1920, Empress Eugenie died in Madrid; Clémentine and her husband welcomed her remains in Southampton before attending the funeral ceremonies that took place in Great Britain.[92][93] The inheritance that Victor received from the late Empress allowed him to curb his financial difficulties. Clémentine and her family then spent part of the year at Farnborough Hill, which they heavily renovated.[94][95] In Belgium, they were present during official visits by foreign sovereigns: King Victor Emmanuel III and Queen Elena of Italy in 1922, the King Alfonso XIII and Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain in 1923, and King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie of Romania in 1924. On the other hand, Prince and Princess Napoleon frequently traveled to Italy where they met the sovereigns. Clémentine got along particularly well with Queen Elena of Italy.[94]

Managing the inheritance after early widowhood

In April 1926, while staying in Brussels, Prince Victor Napoleon suffered an apoplexy and died on the following 3 May.[96][97] Testimonies poured in from European courts, while the Belgian sovereigns and their son Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant went, as soon as the fatal announcement was made, to Clémentine. The latter had to quickly face the concerns caused by important inheritance taxes to be settled. It was now she who watched over the Bonapartist heritage, but it was economically necessary to proceed with the sale of Farnborough Hill and most of its contents.[96]

Widowed at 53, Clémentine still had to watch over her two barely teenage children. Her son Louis was a day student at the St Michael College in Brussels, but after the death of his father, he benefitted from the teaching of a home tutor. As for her daughter Marie-Clotilde, her brilliant results justified, according to her mother, that she continue her secondary studies in France because, in the eyes of Clémentine, "the studies are far from being quite extensive in Belgium".[98] Clémentine tried to liven up the summer and Christmas holidays in Ronchinne by inviting friends who were likely to get along with her children. This was how she often receives her nephew Prince Charles, Count of Flanders. For her part, Clémentine had renewed the links of yesteryear with her sister Stéphanie. From 1927, every summer saw Stéphanie return to Belgium.[99]

An official role in Belgium

While the Belgian sovereigns kept Stéphanie in a lasting ostracism, Clémentine, for her part, was officially received during public ceremonies and in private in Laeken. She befriended Princess Astrid, Prince Leopold's wife. When King Albert I and Queen Elizabeth made a trip to the Belgian Congo, from 5 June to 31 August, it was the first time that a Belgian sovereign had officially visited the colony.[100] The King attended the inauguration of the railroad linking Bas-Congo to Katanga. In Léopoldville, he inaugurated an equestrian statue of Leopold II, a replica of which stands on the Palace of Laeken, and sent Clémentine a letter containing, according to Dominique Paoli, "a delicate allusion to the work of Leopold II".[101] A few weeks later, King Albert I inaugurated, in Namur and in the presence of Clémentine, a new statue of King Leopold II.[101]

In January 1930, Clémentine and her children went to Rome to attend the wedding of Princess Marie-José of Belgium with Umberto, Prince of Piedmont and heir of the throne of Italy. She had rejoiced the previous year at the signing of the Lateran Treaty (11 February 1929) which she considered "the greatest event of modern times".[102] In Rome, Clémentine thought that her daughter Marie-Clotilde could meet a serious suitor during the nuptial ceremonies. She received a proposal from Prince Adalberto, Duke of Bergamo, a cousin of the King of Italy, but she declined this offer: "Marie-Clotilde could do better on the Spanish side, but she does not like Spain and then, I do not yet have clear information on the health of the son and heir — the only good thing — of the King".[103] When she returned from Rome, Marie-Clotilde began to suffer from a pronounced scoliosis, which required her to be immobilized in a medical device for a year. Financially, Ronchinne's property had been mismanaged and Clémentine had to remedy this; she sometimes took care of the garden herself because she had to dismiss half of her twenty servants.[104]

In the spring of 1931, Marie-Clotilde's state of health began to improve. The following summer, Clémentine rented a villa in De Haan, near Ostend, where her daughter was being cared for. In autumn, the young girl returned to her mother, whom she accompanied everywhere. Clémentine also had a few health problems, including kidney disease and arthritis attacks.[105] The 1930s were marked by happy events, such as Stéphanie's visits to Belgium and the stays of her son Louis who continued his studies in Switzerland. In 1934 and 1935, in the space of eighteen months, two mournful events affected Clementine: the deaths of King Albert I, then his daughter-in-law Queen Astrid who tragically lost her life in a car accident.[106]

In January 1935, Prince Louis Napoleon celebrated his majority. Clémentine gave him a car, a Bugatti Type 57. From 1937, Clémentine moved to Ronchinne after having ceded her house on Avenue Louise in Brussels to her son. When her health allowed it, Clémentine traveled, preferably in the south of France and in Italy. Clémentine often visited Marie-Clotilde, who had moved to Paris in the fall of 1937.[107]

Last years and death

In February 1938, while Stéphanie stayed with her in Southern France, Clémentine was subjected to bronchitis with general intoxication which was complicated by infectious influenza and streptococcus. In October 1938, her daughter Marie-Clotilde married Count Serge de Witt, a former captain of the Imperial Russian Army and twenty years her senior, in London, a union that Clémentine disapproved of before resolving her feelings towards it. Shortly after the birth of her first grandchild, Marie-Eugénie, in August 1939, Clémentine, then in Ronchinne, saw World War II with concern. She had been recovering since a new illness had nearly killed her a few months earlier, in May 1939. After the harsh winter of 1939–1940, Clémentine returned to France: She was forced to stay there after the invasion of Belgium in May 1940. Her son Louis joined the Foreign Legion before joining the Resistance; Clémentine was very proud of his behavior during the conflict. During the war, she remained in France: first in Charente, with her friends the Taittinger family, then she rented a villa in Le Cannet, before occupying another in Tresserve, near Aix-les-Bains.[108]

After 1945, the Royal Question, which agitated Belgium, saddened her and encouraged her to live most of the time in France. Her sister Stéphanie, whom she had not seen since 1938, died in Hungary in 1945. The last ten years of her life were peaceful, but quite lonely. After the war, her son Louis discovered his country where General de Gaulle authorized him to remain unofficially before the official repeal, in 1950, of the law of exile.[109] In 1949, he married Alix de Foresta, a member of a noble family originally in Lombardy from the 13th century, before they settled in Provence early in the 16th century. In 14 years (1939–1953), Clémentine became the grandmother of 11 surviving grandchildren, whom she saw from time to time. In 1952, she received the Legion of Honour on occasion of her 80th birthday.[110]

In October 1954,[111] Clémentine left Belgium to return to the Côte d'Azur where, not appreciating hotel life, she rented the Clair-Vallon Villa in Cimiez, a residential district of Nice. She died there from heart disease[112] on Tuesday evening of 8 March 1955 at the age of 82.[113] Louis could see his mother in extremis, but Marie-Clotilde arrived a moment too late. After a religious ceremony, Clémentine 's body is temporarily deposited at the Franciscan monastery of Cimiez.[114] Three months later, according to her last wishes, she was buried with her husband in the Imperial Chapel of Ajaccio on 18 June 1955. Both coffins were transported from mainland France to Corsica on the L'Albatros escorted by the French Navy.[113][115][116]

Titles and heraldry

Titles

At her birth, as the daughter of King Leopold II, Clémentine was titled Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Duchess in Saxony, with the predicate of Royal Highness, according to the titles of her house, and bears the unofficial title of Princess of Belgium, which will be officially regularized by Royal Decree dated 14 March 1891.[15]

The titles worn in 2020 by the members of House of Bonaparte have no legal existence in France and are considered as courtesy titles. They are assigned by the “Head of the House”. Clémentine was considered by the Bonapartist movement as a de jure Empress consort of the French from 1910 to 1926, then as a de jure Empress Dowager from 1926 to her death.

- 30 July 1872 – 14 March 1891: Her Royal Highness Princess Clémentine of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duchess in Saxony

- 14 March 1891 – 14 November 1910: Her Royal Highness Princess Clémentine of Belgium

- 14 November 1910 – 3 May 1926: Her Imperial Highness Princess Napoleon

- 3 May 1926 - 8 March 1955: Her Imperial Highness the Dowager Princess Napoleon

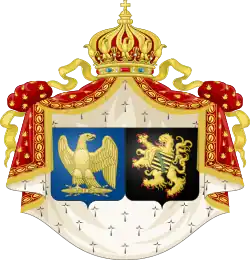

Heraldry

Coat of Arms of Clementine of Belgium as Princess Napoleon and de jure Empress consort of the French |

Posterity and Honours

Toponymy

- Avenue Clémentine runs through Saint-Gilles and Forest.[117]

- The Clémentine Square was inaugurated in 1904 at Laeken.[118]

- There is a Rue Clémentine in Ixelles and Antwerp, a Clémentine Square in Ostend, as well as an Avenue Clémentine in Ghent, at De Haan and at Spa.

- La Clémentine is a yacht built in 1887 and acquired in 1897 by King Leopold II. In 1918, under the English flag, the vessel ran aground on the English coast.[119]

- The Princess Clémentine steamboat is one of the seven who connected Ostend to Dover. Built in 1896 by the Cockerill shipyards in Antwerp, this steamboat was commissioned in 1897. Several times damaged, the boat was designed to transport Belgian and British troops from 1914. Put in reserve in 1923, the trunk was sold in 1928 for demolition.[120]

Painting

- Around 1880: portrait by Louis Gallait.[121]

- Around 1900: full-length portrait by Emile Wauters, initially kept at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, then at the Charlier Museum in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode.[122]</ref>

- 1913: portrait of Clémentine and her daughter in the style of the King of Rome, by André Brouillet presented at the Salon du Paris.[123]

Honours

France

France

Knight of the Legion of Honour (1952)[124]

Knight of the Legion of Honour (1952)[124]

Notes

- Laetitia de Witt names Prince Victor's mistress "Marie Biot".[39]

References

- Defrance 2001, p. 26.

- Paoli 1998, p. 13.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 327–328.

- "Baptême de la Princesse Clémentine". L'Indépendance Belge (in French) (248): 1–2. 3 September 1872. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- Paoli 1998, p. 18.

- "De opvoeding van Belgische prinsen en prinsessen in de negentiende eeuw (Marleen Boden)". ethesis.net (in Dutch). 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- de Witt 2007, p. 328.

- Paoli 1998, p. 23.

- Paoli 1998, p. 21.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 25–28.

- Bilteryst 2013, p. 206.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 31–32.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 36–37.

- "Courrier de Spa". La Meuse (in French) (182): 2. 1 August 1890. Retrieved July 23, 2021..

- Bilteryst 2013, pp. 255–258.

- de Witt 2007, p. 329.

- Bilteryst 2013, p. 258.

- Paoli 1998, p. 68.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 329–330.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 65–69.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 65–66.

- de Witt 2007, p. 330.

- Defrance 2001, p. 140.

- Defrance 2001, pp. 203–204.

- Defrance 2001, pp. 229–230.

- Paoli 1998, p. 73.

- Schiel 1980, p. 222.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 77–78.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 78–79.

- Paoli 1998, p. 80.

- Paoli 1998, p. 81.

- Kerckvoorde 2001, p. 229.

- Defrance 2001, p. 182.

- de Witt 2007, p. 334.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 93–94.

- de Witt 2007, p. 332.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 24–25.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 335–336.

- de Witt 2007, p. 323.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 323–324.

- de Witt 2007, p. 221.

- Paoli 1998, p. 103.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 104–105.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 336–337.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 337–338.

- Paoli 1998, p. 107.

- de Witt 2007, p. 340.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 107–108.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 344–345.

- "Petite chronique". Le Peuple (in French) (43): 1. 12 May 1905. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- "Petite chronique". Le Peuple (in French) (74): 1. 15 March 1905. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 115–120.

- de Witt 2007, p. 351.

- Omer Vandeputte; Filip Devos (2007). Gids voor Vlaanderen : toeristische en culturele gids voor alle steden en dorpen in Vlaanderen (in Dutch). Lannoo. p. 841. ISBN 9789020959635. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- Wim van der Elst (2003–2004). "Edwin Ganz (1871 – 1948) : van schilder van militaire taferelen tot schilder van paarden en Brabantse landschappen uit onze streek" (PDF) (in Dutch). 15. LACA-Tijdingen: 27–37. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - de Witt 2007, pp. 351–352.

- Paoli 1998, p. 121.

- Énache 1999, p. 209.

- "Le mariage de la princesse Clémentine". L'Indépendance Belge (in French) (304): 2. 31 October 1910. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 354–355.

- Emilio (15 November 1910). "Le mariage de S.A.I. le Prince Napoléon et de S.A.R. la Princesse Clémentine". Le Figaro (in French) (319): 3. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 120–137.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 356–358.

- Paoli 1998, p. 157.

- de Witt 2007, p. 222 and 384.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 157–158.

- de Witt 2007, p. 384.

- Énache 1999, pp. 197–198.

- "Le domaine de Ronchinne". Journal de Bruxelles (in French) (124): 1. 4 May 1913. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- de Witt 2007, p. 387.

- Paoli 1998, p. 161.

- Olivier Defrance (2006). Clémentine de Belgique (1872-1955). pp. 108–109. ISBN 9782873864347.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - de Witt 2007, p. 358.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 161–169.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 174–178.

- de Witt 2007, p. 393.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 391–392.

- de Witt 2007, p. 392.

- Maria Biermé (29 November 1915). "Notre princesse". L'Indépendance Belge (in French) (282): 2. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- Paoli 1998, p. 179.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 180–181.

- Paoli 1998, p. 186.

- de Witt 2007, p. 398.

- de Witt 2007, p. 313.

- de Witt 2007, p. 360.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 366–367.

- de Witt 2007, p. 402.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 401–402.

- de Witt 2007, p. 401 and 403.

- de Witt 2007, p. 406.

- de Witt 2007, p. 435.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 187–188.

- de Witt 2007, p. 423.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 190–193.

- de Witt 2007, p. 424.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 193–195.

- de Witt 2007, p. 433.

- Paoli 1998, p. 196.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 197–198.

- "Les souverains belges qui ont visité le Congo". RTBF (in French). 10 May 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- Paoli 1998, p. 200.

- Paoli 1998, p. 206.

- Paoli 1998, p. 202.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 204–205.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 209–210.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 211–220.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 221–225.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 225–228.

- "Le prince Louis-Napoléon". Le Monde (in French). 16 August 1969. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 229–231.

- Dumont 1959, p. 83.

- Reuter (9 March 1955). "La princesse Clémentine n'est plus". Journal de Genève (in French) (57): 3. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- Tourtchine 1999, p. 94.

- Paoli 1998, pp. 231–232.

- de Witt 2007, pp. 7–9.

- de Witt 2007, p. 427.

- Région de Bruxelles-Capitale. "Saint-Gilles, Forest, Avenue Clémentine". Inventaire du patrimoine architectural (in French). Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- Région de Bruxelles-Capitale. "Laeken, Square Clémentine". Inventaire du patrimoine architectural (in French). Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- "La Clémentine". marinebelge.be (in French). 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- "Malles OSTEND-DOVER pré 1940 (historique)". belgian-navy.be (in French). 2 January 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- Paoli 1998, p. 22.

- Dumont 1959, p. 89.

- Paoli 1998, p. 146.

- Paoli 1998, p. 230.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Princess Clémentine of Belgium |

|---|

Bibliography

- Bilteryst, Damien (2013). Le prince Baudouin: Frère du Roi-Chevalier (in French). Brussels: Éditions Racine. ISBN 978-2-87386-847-5.

- Defrance, Olivier (2001). Louise de Saxe-Cobourg:Amours, argent, procès (in French). Brussels: Éditions Racine. ISBN 978-2-87386-230-5.

- de Witt, Laetitia (2007). Le Prince Victor Napoléon (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-63127-1.

- Dumont, Georges-Henri (1959). La dynastie belge (in French). Paris-Brussels: Elsevier.

- Énache, Nicolas (1999). La descendance de Marie-Thérèse de Habsburg (in French). Paris: Éditions L'intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux. ISBN 978-2-908003-04-8.

- Kerckvoorde, Mia (2001). Marie-Henriette: une amazone face à un géant. ISBN 2-87386-261-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Paoli, Dominique (1998). Clémentine, Princesse Napoléon (in French). Brussels: Éditions Racine. ISBN 978-2-87386-128-5.

- Schiel, Irmgard (1980). Stéphanie princesse héritière dans l'ombre de Mayerling. ISBN 978-3-421-01867-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Tourtchine, Jean-Fred (1999). Jean-Fred Tourtchine (ed.). Les manuscrits du CEDRE – L'Empire des Français. ASIN B000WTIR9U.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

.JPG.webp)