Woodblock printing

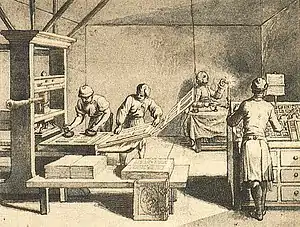

Woodblock printing or block printing is a technique for printing text, images or patterns used widely throughout East Asia and originating in China in antiquity as a method of printing on textiles and later paper. Each page or image is created by carving a wooden block to leave only some areas and lines at the original level; it is these that are inked and show in the print, in a relief printing process. Carving the blocks is skilled and laborious work, but a large number of impressions can then be printed.

As a method of printing on cloth, the earliest surviving examples from China date to before 220 AD. Woodblock printing existed in Tang China by the 7th century AD and remained the most common East Asian method of printing books and other texts, as well as images, until the 19th century. Ukiyo-e is the best-known type of Japanese woodblock art print. Most European uses of the technique for printing images on paper are covered by the art term woodcut, except for the block books produced mainly in the 15th century.

History

China

According to the Book of the Southern Qi, in the 480s, a man named Gong Xuanyi (龔玄宜) styled himself Gong the Sage and "said that a supernatural being had given him a 'jade seal jade block writing,' which did not require a brush: one blew on the paper and characters formed."[1] He then used his powers to mystify a local governor. Eventually he was dealt with by the governor's successor, who presumably executed Gong.[2] Timothy Hugh Barrett postulates that Gong's magical jade block was actually a printing device, and Gong was one of the first, if not the first printer. The semi-mythical record of him therefore describes his usage of the printing process to deliberately bewilder onlookers and create an image of mysticism around himself.[3] However woodblock print flower patterns applied to silk in three colours have been found dated from the Han dynasty (before AD 220).[4]

The rise of printing was greatly influenced by Mahayana Buddhism. According to Mahayana beliefs, religious texts hold intrinsic value for carrying the Buddha's word and act as talismanic objects containing sacred power capable of warding off evil spirits. By copying and preserving these texts, Buddhists could accrue personal merit. As a consequence the idea of printing and its advantages in replicating texts quickly became apparent to Buddhists, who by the 7th century, were using woodblocks to create apotropaic documents. These Buddhist texts were printed specifically as ritual items and were not widely circulated or meant for public consumption. Instead they were buried in consecrated ground. The earliest extant example of this type of printed matter is a fragment of a dhāraṇī (Buddhist spell) miniature scroll written in Sanskrit unearthed in a tomb in Xi'an. It is called the Great spell of unsullied pure light (Wugou jingguang da tuoluoni jing 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經) and was printed using woodblock during the Tang dynasty, c. 650–670 AD.[5] A similar piece, the Saddharma pundarika sutra, was also discovered and dated to 690 to 699.[6]

This coincides with the reign of Wu Zetian, under which the Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, which advocates the practice of printing apotropaic and merit making texts and images, was translated by Chinese monks.[5] The oldest extant evidence of woodblock prints created for the purpose of reading are portions of the Lotus Sutra discovered at Turpan in 1906. They have been dated to the reign of Wu Zetian using character form recognition.[5] The oldest text containing a specific date of printing was discovered in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang in 1907 by Aurel Stein. This copy of the Diamond Sutra is 14 feet long and contains a colophon at the inner end, which reads: "Reverently [caused to be] made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong [i.e. 11 May, AD 868 ]". It is considered the world's oldest securely dated woodblock scroll.[5] The Diamond sutra was closely followed by the earliest extant printed almanac, the Qianfu sinian lishu (乾符四年曆書), dated to 877.[5]

Spread

Evidence of woodblock printing appeared in Korea and Japan soon afterward. The Great Dharani Sutra (Korean: 무구정광대다라니경/無垢淨光大陀羅尼經, romanized: Muggujeonggwang Daedharanigyeong) was discovered at Bulguksa, South Korea in 1966 and dated between 704 and 751 in the era of Later Silla. The document is printed on a 8 cm × 630 cm (3.1 in × 248.0 in) mulberry paper scroll.[7] A dhāraṇī sutra was printed in Japan around AD 770. One million copies of the sutra, along with other prayers, were ordered to be produced by Empress Shōtoku. As each copy was then stored in a tiny wooden pagoda, the copies are together known as the Hyakumantō Darani (百万塔陀羅尼, "1,000,000 towers/pagodas Darani").[5][8]

Woodblock printing spread across Eurasia by 1000 AD and could be found in the Byzantine Empire. However printing onto cloth only became common in Europe by 1300. "In the 13th century the Chinese technique of blockprinting was transmitted to Europe",[9] soon after paper became available in Europe.

Song dynasty

From 932 to 955 the Twelve Classics and an assortment of other texts were printed. During the Song dynasty, the Directorate of education and other agencies used these block prints to disseminate their standardized versions of the Classics. Other disseminated works include the Histories, philosophical works, encyclopedias, collections, and books on medicine and the art of war.[5]

In 971 work began on the complete Tripiṭaka Buddhist Canon (Kaibao zangshu 開寶藏書) in Chengdu. It took 10 years to finish the 130,000 blocks needed to print the text. The finished product, the Sichuan edition of the Kaibao canon, also known as the Kaibao Tripitaka, was printed in 983.[5]

Prior to the introduction of printing, the size of private collections in China had already seen an increase since the invention of paper. Fan Ping (215–84) had in his collection 7,000 rolls (juan), or a few hundred titles. Two centuries later, Zhang Mian owned 10,000 juan, Shen Yue (441–513) 20,000 juan, and Xiao Tong and his cousin Xiao Mai both had collections of 30,000 juan. Emperor Yuan of Liang (508–555) was said to have had a collection of 80,000 juan. The combined total of all known private book collectors prior to the Song dynasty number around 200, with the Tang alone accounting for 60 of them.[10]

Following the maturation of woodblock printing, official, commercial, and private publishing businesses emerged while the size and number of collections grew exponentially. The Song dynasty alone accounts for some 700 known private collections, more than triple the number of all the preceding centuries combined. Private libraries of 10–20,000 juan became commonplace while six individuals owned collections of over 30,000 juan. The earliest extant private Song library catalogue lists 1,937 titles in 24,501 juan. Zhou Mi's collection numbered 42,000 juan, Chen Zhensun's collection lists 3,096 titles in 51,180 juan, and Ye Mengde (1077–1148) as well as one other individual owned libraries of 6,000 titles in 100,000 juan. The majority of which were secular in nature. Texts contained material such as medicinal instruction or came in the form of a leishu (類書), a type of encyclopedic reference book used to help examination candidates.[5][10]

Imperial establishments such as the Three Institutes: Zhaowen Institute, History Institute, and Jixian Institute also followed suit. At the start of the dynasty the Three Institutes' holdings numbered 13,000 juan, by the year 1023 39,142 juan, by 1068 47,588 juan, and by 1127 73,877 juan. The Three Institutes were one of several imperial libraries, with eight other major palace libraries, not including imperial academies.[11] According to Weng Tongwen, by the 11th century, central government offices were saving tenfold by substituting earlier manuscripts with printed versions.[12] The impact of woodblock printing on Song society is illustrated in the following exchange between Emperor Zhenzong and Xing Bing in the year 1005:

The emperor went to the Directorate of Education to inspect the Publications Office. He asked Xing Bing how many woodblocks were kept there. Bing replied, "At the start of our dynasty, there were fewer than four thousand. Today, there are more than one hundred thousand. The classics and histories, together with standard commentaries, are all fully represented. When I was young and devoted myself to learning, there were only one or two scholars in every hundred who possessed copies of all the classics and commentaries. There was no way to copy so many works. Today, printed editions of these works are abundant, and officials and commoners alike have them in their homes. Scholars are fortunate indeed to have been born in such an era as ours![13]

In 1076, the 39 year old Su Shi remarked upon the unforeseen effect an abundance of books had on examination candidates:

I can recall meeting older scholars, long ago, who said that when they were young they had a hard time getting their hands on a copy of Shiji or Han shu. If they were lucky enough to get one, they thought nothing of copying the entire text out by hand, so they could recite it day and night. In recent years merchants engrave and print all manner of books belonging to the hundred schools, and produce ten thousand pages a day. With books so readily available, you would think that students' writing and scholarship would be many times better than what they were in earlier generations. Yet, to the contrary, young men and examination candidates leave their books tied shut and never look at them, preferring to amuse themselves with baseless chatter. Why is this?[14]

Woodblock printing also changed the shape and structure of books. Scrolls were gradually replaced by concertina binding (經摺裝) from the Tang period onward. The advantage was that it was now possible to flip to a reference without unfolding the entire document. The next development known as whirlwind binding (xuanfeng zhuang 旋風裝) was to secure the first and last leaves to a single large sheet, so that the book could be opened like an accordion.[15]

Around the year 1000, butterfly binding was developed. Woodblock prints allowed two mirror images to be easily replicated on a single sheet. Thus two pages were printed on a sheet, which was then folded inwards. The sheets were then pasted together at the fold to make a codex with alternate openings of printed and blank pairs of pages. In the 14th century the folding was reversed outwards to give continuous printed pages, each backed by a blank hidden page. Later the sewn bindings were preferred rather than pasted bindings.[16] Only relatively small volumes (juan 卷) were bound up, and several of these would be enclosed in a cover called a tao, with wooden boards at front and back, and loops and pegs to close up the book when not in use. For example, one complete Tripitaka had over 6,400 juan in 595 tao.[17]

Ming dynasty

Despite the productive effect of woodblock printing, historian Endymion Wilkinson notes that it never supplanted handwritten manuscripts. Indeed, manuscripts remained dominant until the very end of Imperial China:

As a result of block-printing technology, it became easier and cheaper to produce multiple copies of books quickly. By the eleventh century, the price of books had fallen by about one tenth what they had been before and as a result they were more widely disseminated. Nevertheless, even in the fifteenth century most books in major libraries were still in manuscript, not in print. Almost to the end of the empire it remained cheaper to pay a copyist than to buy a printed book. Seven hundred and fifty years after the first imperially sponsored printed works in the Northern Song, the greatest book project of the eighteenth century, the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries (四庫全書), was produced as a manuscript, not as a printed collection. About 4 percent of it was printed in movable type in 1773, but it was hand-carved movable wooden type. Indeed, the entire collection was only printed for the first time in the 1980s. Access to books, especially large works, such as the Histories, remained difficult right into the twentieth century.[18]

— Endymion Wilkinson

Not only did manuscripts remain competitive with imprints,[19] they were even preferred by elite scholars and collectors. The age of printing gave the act of copying by hand a new dimension of cultural reverence. Those who considered themselves real scholars and true connoisseurs of the book did not consider imprints to be real books. Under the elitist attitudes of the time, "printed books were for those who did not truly care about books."[20]

However, copyists and manuscript only continued to remain competitive with printed editions by dramatically reducing their price. According to the Ming dynasty author Hu Yinglin, "if no printed edition were available on the market, the hand-copied manuscript of a book would cost ten times as much as the printed work,"[21] also "once a printed edition appeared, the transcribed copy could no longer be sold and would be discarded."[21] The result is that despite the mutual co-existence of hand-copied manuscripts and printed texts, the cost of the book had declined by about 90 percent by the end of the 16th century.[21] As a result, literacy increased. In 1488, the Korean Choe Bu observed during his trip to China that "even village children, ferrymen, and sailors" could read, although this applied mainly to the south while northern China remained largely illiterate.[22]

Three-five colored prints

%252C_from_the_Mustard_Seed_Garden_Manual_of_Painting_MET_DP-14004-001.jpg.webp)

In modern times, Chinese printing continued the tradition begun in medieval times. Black-and-white woodcuts were generally replaced by colored ones, achieved by printing successive runs with different inks. Between the end of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th century, three—and five—color prints appeared. The oldest surviving print is the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Paintings (1644) by Hu Zhengyan, of which there are several copies in various museums and collections. It is still commonly reproduced in China today and its images are very popular: it includes landscapes, flowers, animals, reproductions of jades, bronzes, porcelain and other objects.[23]

Another outstanding series is the collection of twenty-nine Kaempfer Prints (British Museum, London), brought in 1693 by a German physician from China to Europe, which includes flowers, fruits, birds, insects and ornamental motifs reminiscent of the style of Kangxi ceramics. Equally famous is the compilation Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, published in two parts between 1679 and 1701. It was initiated by the scholar and landscape painter Wáng Gài and expanded and prefaced by the art critic Li Yu and the landscape painter Wáng Niè. It was noted for the quality of its polychrome and drawings, which influenced Qing painting.[24]

Goryeo

In 989 Seongjong of Goryeo sent the monk Yeoga to request from the Song a copy of the complete Buddhist canon. The request was granted in 991 when Seongjong's official Han Eongong visited the Song court.[25] In 1011, Hyeonjong of Goryeo issued the carving of their own set of the Buddhist canon, which would come to be known as the Goryeo Daejanggyeong. The project was suspended in 1031 after Heyongjong's death, but work resumed again in 1046 after Munjong's accession to the throne. The completed work, amounting to some 6,000 volumes, was finished in 1087. Unfortunately the original set of woodblocks was destroyed in a conflagration during the Mongol invasion of 1232. King Gojong ordered another set to be created and work began in 1237, this time only taking 12 years to complete. In 1248 the complete Goryeo Daejanggyeong numbered 81,258 printing blocks, 52,330,152 characters, 1496 titles, and 6568 volumes. Due to the stringent editing process that went into the Goryeo Daejanggyeong and its surprisingly enduring nature, having survived completely intact over 760 years, it is considered the most accurate of Buddhist canons written in Classical Chinese as well as a standard edition for East Asian Buddhist scholarship.[26]

Japan

In the Kamakura period from the 12th century to the 13th century, many books were printed and published by woodblock printing at Buddhist temples in Kyoto and Kamakura.[27]

The mass production of woodblock prints in the Edo period was due to the high literacy rate of Japanese people. The literacy rate of the Japanese by 1800 was almost 100% for the samurai class and 50% to 60% for the chōnin and nōmin (farmer) class due to the spread of private schools terakoya. There were more than 600 rental bookstores in Edo, and people lent woodblock-printed illustrated books of various genres. The content of these books varied widely, including travel guides, gardening books, cookbooks, kibyōshi (satirical novels), sharebon (books on urban culture), kokkeibon (comical books), ninjōbon (romance novel), yomihon, kusazōshi, art books, play scripts for the kabuki and jōruri (puppet) theatre, etc. The best-selling books of this period were Kōshoku Ichidai Otoko (Life of an Amorous Man) by Ihara Saikaku, Nansō Satomi Hakkenden by Takizawa Bakin, and Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige by Jippensha Ikku, and these books were reprinted many times.[27][28][29][30]

From the 17th century to the 19th century, ukiyo-e depicting secular subjects became very popular among the common people and were mass-produced. ukiyo-e is based on kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, beautiful women, landscapes of sightseeing spots, historical tales, and so on, and Hokusai and Hiroshige are the most famous artists. In the 18th century, Suzuki Harunobu established the technique of multicolor woodblock printing called nishiki-e and greatly developed Japanese woodblock printing culture such as ukiyo-e. Ukiyo-e influenced European Japonisme and Impressionism. In the early 20th century, shin-hanga that fused the tradition of ukiyo-e with the techniques of Western paintings became popular, and the works of Hasui Kawase and Hiroshi Yoshida gained international popularity.[27][28][31][32]

Asia and North Africa

A few specimen of wood block printing, possibly called tarsh in Arabic,[33] have been excavated from a 10th-century context in Arabic Egypt. They were mostly used for prayers and amulets. The technique may have spread from China or been an independent invention,[34] but had very little impact and virtually disappeared at the end of the 14th century.[35] In India the main importance of the technique has always been as a method of printing textiles, which has been a large industry since at least the 10th century.[36] Nowadays wooden block printing is commonly used for creating beautiful textiles, such as block print saree, kurta, curtains, kurtis, dress, shirts, cotton sarees.[37]

Europe

Block books, where both text and images are cut on a single block for a whole page, appeared in Europe in the mid-15th century. As they were almost always undated, and without statement of printer or place of printing, determining their dates of printing has been an extremely difficult task. Allan H. Stevenson, by comparing the watermarks in the paper used in block books with watermarks in dated documents, concluded that the "heyday" of block books was the 1460s, but that at least one dated from about 1451.[38][39] Block books printed in the 1470s were often of cheaper quality, as a cheaper alternative to books printed by printing press.[40] Block books continued to be printed sporadically up through the end of the 15th century.[38]

The method was also used extensively for printing playing cards.[41]

China

Ceramic and wooden movable type were invented in the Northern Song dynasty around the year 1041 by the commoner Bi Sheng. Metal movable type also appeared in the Southern Song dynasty. The earliest extant book printed using movable type is the Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union, printed in Western Xia c. 1139–1193. Metal movable type was used in the Song, Jin, and Yuan dynasties for printing banknotes. The invention of movable type did not have an immediate effect on woodblock printing and it never supplanted it in East Asia.

Only during the Ming and Qing dynasties did wooden and metal movable types see any considerable use, but the preferred method remained woodblock. Usage of movable type in China never exceeded 10 percent of all printed materials while 90 percent of printed books used the older woodblock technology. In one case an entire set of wooden type numbering 250,000 pieces was used for firewood.[15] Woodblocks remained the dominant printing method in China until the introduction of lithography in the late 19th century.[42]

Traditionally it has been assumed that the prevalence of woodblock printing in East Asia as a result of Chinese characters led to the stagnation of printing culture and enterprise in that region. S. H. Steinberg describes woodblock printing in his Five Hundred Years of Printing as having "outlived their usefulness" and their printed material as "cheap tracts for the half-literate, [...] which anyway had to be very brief because of the laborious process of cutting the letters."[43] John Man's The Gutenberg Revolution makes a similar case: "wood-blocks were even more demanding than manuscript pages to make, and they wore out and broke, and then you had to carve another one – a whole page at a time."[43]

Recent commentaries on printing in China using contemporary European observers with first hand knowledge complicate the traditional narrative. T. H. Barrett points out that only Europeans who had never seen Chinese woodblock printing in action tended to dismiss it, perhaps due to the almost instantaneous arrival of both xylography and movable type in Europe. The early Jesuit missionaries of late 16th century China, for instance, had a similar distaste for wood based printing for very different reasons. These Jesuits found that "the cheapness and omnipresence of printing in China made the prevailing wood-based technology extremely disturbing, even dangerous."[44] Matteo Ricci made note of "the exceedingly large numbers of books in circulation here and the ridiculously low prices at which they are sold."[45] Two hundred years later the Englishman John Barrow, by way of the Macartney mission to Qing China, also remarked with some amazement that the printing industry was "as free as in England, and the profession of printing open to everyone."[44] The commercial success and profitability of woodblock printing was attested to by one British observer at the end of the nineteenth century, who noted that even before the arrival of western printing methods, the price of books and printed materials in China had already reached an astoundingly low price compared to what could be found in his home country. Of this, he said:

We have an extensive penny literature at home, but the English cottager cannot buy anything like the amount of printed matter for his penny that the Chinaman can for even less. A penny Prayer-book, admittedly sold at a loss, cannot compete in mass of matter with many of the books to be bought for a few cash in China. When it is considered, too, that a block has been laboriously cut for each leaf, the cheapness of the result is only accounted for by the wideness of sale.[46]

Other modern scholars such as Endymion Wilkinson hold a more conservative and skeptical view. While Wilkinson does not deny "China's dominance in book production from the fourth to the fifteenth century," he also insists that arguments for the Chinese advantage "should not be extended either forwards or backwards in time."[47]

European book production began to catch up with China after the introduction of the mechanical printing press in the mid fifteenth century. Reliable figures of the number of imprints of each edition are as hard to find in Europe as they are in China, but one result of the spread of printing in Europe was that public and private libraries were able to build up their collections and for the first time in over a thousand years they began to match and then overtake the largest libraries in China.[47]

— Endymion Wilkinson

Decline of woodblock printing in China

During the 16th and 17th centuries, printmaking enjoyed great popularity, especially in the illustration of books such as Buddhist texts, poems, novels, biographies, medical treatises, music, etc. The major center of production was initially in Kien-ngan (Fujian) and, from the 17th century, in Sin-ngan (Anhui) and Nanjing (Jiangsu). On the other hand, in the 18th century, the industry began to decline, with stereotyped images. This coincided with the arrival of European missionaries who introduced Western engraving techniques. The Jesuit Matteo Ripa edited in 1714-1715 a series of poems by Emperor Kangxi, which he illustrated with landscapes of the imperial summer residence at Jehol. During the reign of Emperor Qianlong the one hundred and four maps of the Chinese Empire made by Jesuit missionaries were printed, as well as illustrations of his military victories, which he commissioned in Paris from the engraver Charles-Nicolas Cochin (Conquests of the Emperor of China, 1767–1773). The emperor himself commissioned the Jesuits to instruct Chinese artisans in the intaglio technique, but they did not obtain good results. Already in the 19th century, the growing xenophobia against Europeans was progressively relegating the use of engraving in China.[48]

In the 20th century, the genre was revived by the writer Lou Siun, who founded a woodcut school in Shanghai in 1930. Influenced by contemporary Russian engraving, this school dealt especially with popular, agricultural and military subjects for propaganda purposes, as is evident in the work of P'an Jeng and Huang Yong-yu.[49]

Korea

In 1234, cast metal movable type was used in Goryeo (Korea) to print the 50-volume Prescribed Texts for Rites of the Past and Present, compiled by Choe Yun-ui, but no copies survived to the present.[50] The oldest extant book printed with movable metal type is the Jikji of 1377.[51] This form of metal movable type was described by the French scholar Henri-Jean Martin as "extremely similar to Gutenberg's".[52]

Movable type never replaced woodblock printing in Korea. Indeed, even the promulgation of Hangeul was done through woodblock prints. The general assumption is that movable type did not replace block printing in places that used Chinese characters due to the expense of producing more than 200,000 individual pieces of type. Even woodblock printing was not as cost productive as simply paying a copyist to write out a book by hand if there was no intention of producing more than a few copies. Although Sejong the Great introduced Hangeul, an alphabetic system, in the 15th century, Hangeul only replaced Hanja in the 20th century.[53] And unlike China, the movable type system was kept mainly within the confines of a highly stratified elite Korean society:

Korean printing with movable metallic type developed mainly within the royal foundry of the Yi dynasty. Royalty kept a monopoly of this new technique and by royal mandate suppressed all non-official printing activities and any budding attempts at commercialization of printing. Thus, printing in early Korea served only the small, noble groups of the highly stratified society.[54]

— Sohn Pow-Key

Japan

Western style movable type printing-press was brought to Japan by Tenshō embassy in 1590, and was first printed in Kazusa, Nagasaki in 1591. However, western printing-press were discontinued after the ban on Christianity in 1614.[27][55] The moveable type printing-press seized from Korea by Toyotomi Hideyoshi's forces in 1593 was also in use at the same time as the printing press from Europe. An edition of the Confucian Analects was printed in 1598, using a Korean moveable type printing press, at the order of Emperor Go-Yōzei.[27][56]

Tokugawa Ieyasu established a printing school at Enko-ji in Kyoto and started publishing books using domestic wooden movable type printing-press instead of metal from 1599. Ieyasu supervised the production of 100,000 types, which were used to print many political and historical books. In 1605, books using domestic copper movable type printing-press began to be published, but copper type did not become mainstream after Ieyasu died in 1616.[27]

The great pioneers in applying movable type printing press to the creation of artistic books, and in preceding mass production for general consumption, were Honami Kōetsu and Suminokura Soan. At their studio in Saga, Kyoto, the pair created a number of woodblock versions of the Japanese classics, both text and images, essentially converting emaki (handscrolls) to printed books, and reproducing them for wider consumption. These books, now known as Kōetsu Books, Suminokura Books, or Saga Books, are considered the first and finest printed reproductions of many of these classic tales; the Saga Book of the Tales of Ise (Ise monogatari), printed in 1608, is especially renowned. Saga Books were printed on expensive paper, and used various embellishments, being printed specifically for a small circle of literary connoisseurs.[57] For aesthetic reasons, the typeface of the Saga-bon, like that of traditional handwritten books, adopted the renmen-tai (ja), in which several characters are written in succession with smooth brush strokes. As a result, a single typeface was sometimes created by combining two to four semi-cursive and cursive kanji or hiragana characters. In one book, 2,100 characters were created, but 16% of them were used only once.[58][59][60]

Despite the appeal of moveable type, however, craftsmen soon decided that the semi-cursive and cursive script style of Japanese writings was better reproduced using woodblocks. By 1640 woodblocks were once again used for nearly all purposes.[61] After the 1640s, movable type printing declined, and books were mass-produced by conventional woodblock printing during most of the Edo period. It was after the 1870s, during the Meiji period, when Japan opened the country to the West and began to modernize, that this technique was used again.[27][62]

Middle East

In countries using Arabic scripts, works, especially the Qur'an were printed from blocks or by lithography in the 19th century, as the links between the characters require compromises when movable type is used which were considered inappropriate for sacred texts.[63]

Europe

Around the mid-1400s, block-books, woodcut books with both text and images, usually carved in the same block, emerged as a cheaper alternative to manuscripts and books printed with movable type. These were all short heavily illustrated works, the bestsellers of the day, repeated in many different block-book versions: the Ars moriendi and the Biblia pauperum were the most common. There is still some controversy among scholars as to whether their introduction preceded or, the majority view, followed the introduction of movable type, with the range of estimated dates being between about 1440–1460.[40]

Technique

Jia xie is a method for dyeing textiles (usually silk) using wood blocks invented in the 5th–6th centuries in China. An upper and a lower block are made, with carved out compartments opening to the back, fitted with plugs. The cloth, usually folded a number of times, is inserted and clamped between the two blocks. By unplugging the different compartments and filling them with dyes of different colours, a multi-coloured pattern can be printed over quite a large area of folded cloth. The method is not strictly printing however, as the pattern is not caused by pressure against the block.[4]

Colour woodblock printing

The earliest woodblock printing known is in colour—Chinese silk from the Han dynasty printed in three colours.[4]

Colour is very common in Asian woodblock printing on paper; in China the first known example is a Diamond sutra of 1341, printed in black and red at the Zifu Temple in modern-day Hubei province. The earliest dated book printed in more than 2 colours is Chengshi moyuan (Chinese: 程氏墨苑), a book on ink-cakes printed in 1606 and the technique reached its height in books on art published in the first half of the 17th century. Notable examples are the Hu Zhengyan's Treatise on the Paintings and Writings of the Ten Bamboo Studio of 1633,[64] and the Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual published in 1679 and 1701.[65]

See also

| Part of a series on the |

| History of printing |

|---|

|

References

- Barrett 2008, p. 60.

- Barrett 2008, p. 50.

- Barrett 2008, p. 61.

- Shelagh Vainker in Anne Farrer (ed), "Caves of the Thousand Buddhas", 1990, British Museum publications, ISBN 0-7141-1447-2

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 910.

- Pan, Jixing (1997). "On the Origin of Printing in the Light of New Archaeological Discoveries". Chinese Science Bulletin. 42 (12): 976–981 [pp. 979–980]. Bibcode:1997ChSBu..42..976P. doi:10.1007/BF02882611. ISSN 1001-6538. S2CID 98230482.

- Andrea Matles Savada, ed. (1993). "Silla". North Korea: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 3 December 2009 – via Countrystudies.us.

• "A History of Writings in Japanese and Current Studies in the Field of Rare Books in Japan". 62nd IFLA General Conference - Conference Proceedings - August 25–31, 1996. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

• "Gutenberg and the Koreans: The Invention of Movable Metal Type Printing in Korea". Rightreading.com. 13 September 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

• "Early Print Culture in Korea". Buddhapia. Hyundae Bulkyo Media Center. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

• "National Treasure No. 126". Cultural Heritage Administration of South Korea. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008.

• "Printed copy of the Diamond Sutra". Collection Items. British Library. The Xiantong era (咸通 Xián tōng) ran from 860–874, crossing the reigns of Yi Zong (懿宗 Yì zōng) and Xi Zong (僖宗 Xī zōng), see List of Tang Emperors. The book was thus prepared in the time of Yi Zong. - "MS 2489". The Schøyen Collection. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- Hsü, Immanuel C. Y. (1970). The Rise of Modern China. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 830. ISBN 0-19-501240-2.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 930.

- Chia 2011, p. 43.

- Chia 2011, p. 21.

- Chia 2011, p. 33.

- Chia 2011, p. 38.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 912.

- "Dunhuang concertina binding findings". Archived from the original on 9 March 2000. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "MS 2540". The Schøyen Collection. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 910-911.

- Kai-Wing Chow (2004). Publishing, Culture, and Power in Early Modern China. Stanford University Press. p. 36.

In late Ming/early Qing China, cost for copying 20 to 30 pages was around .02 to .03 tael, which worked out to something like 0.005 tael per hundred characters, while a carver was typically paid 0.02 to 0.03 tael per hundred characters carved, and could carve 100 to 150 characters a day.

- Chia 2011, p. 41.

- Tsien 1985, p. 373.

- Twitchett 1998b, p. 636.

- Rivière (1966, pp. 577–578)

- Rivière (1966, pp. 578–579)

- Hyun, Jeongwon (2013). Gift Exchange among States in East Asia During the Eleventh Century (PDF) (PhD dissertation). University of Washington. p. 191.

- "Printing woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana and miscellaneous Buddhist scriptures". UNESCO Memory of the World. United Nations. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- The Past, Present and Future of Printing in Japan. Izumi Munemura. (2010). The Surface Finishing Society of Japan.

- Edo Picture Books and the Edo Period. National Diet Library.

- 第6回 和本の楽しみ方4 江戸の草紙. Konosuke Hashiguchi. (2013) Seikei University.

- Nihonbashi. Mitsui Fdosan.

- Shin hanga bringing ukiyo-e back to life. The Japan Times.

- Junko Nishiyama. (2018) 新版画作品集 ―なつかしい風景への旅. p18. Tokyo Bijutsu. ISBN 978-4808711016

- See (Bulliet 1987), p. 427: "The thesis proposed here, that the word tarsh meant "printblock" in the dialect of the medieval Muslim underworld".

- See (Bulliet 1987), p. 435: "Printing in Arabic appears in the Middle East within a century or so of becoming well established in China. Moreover, medieval Arabic chronicles confirm that the craft of paper making came to the Middle East from China by way of Central Asia, and one print was found in the excavation of the medieval Egyptian Red Sea port of al-Qusair al-Qadim where wares imported from China have been discovered. Nevertheless, it seems more likely that Arabic block printing was an independent invention".

- See (Bulliet 1987), p. 427: "Judging from palaeography and the eighth-century date of the introduction of paper to the Islamic world, Arabic block printing must have begun in the ninth or tenth century. It persisted into, but possibly not beyond, the fourteenth century"... "Yet it had so little impact on Islamic society that today only a handful of scholars are aware it ever existed, and no definite textual reference to it has been thought to survive".

- "Ashmolean − Eastern Art Online, Yousef Jameel Centre for Islamic and Asian Art".

- Khan, Irshad (10 February 2023). "Block Printing History, Types, Process and Materials To Be Used". Wooden Printing block. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Carter 2006, p. 46.

- Allan H. Stevenson (Spring 1967). "The Quincentennnial of Netherlandish Blockbooks". British Museum Quarterly. 31 (3/4): 83–87. doi:10.2307/4422966. JSTOR 4422966.

- Master E.S., Alan Shestack, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1967.

- "Early Card painters and Printers in Germany, Austria and Flanders (14th and 15th century)". Trionfi. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 909.

- Barrett 2008, p. 10.

- Barrett 2008, p. 11.

- Twitchett 1998b, p. 637.

- Barrett 2008, p. 14.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 935.

- Rivière (1966, pp. 580–581)

- Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 2110)

- Taylor, Insup; Taylor, Martin M. (1995). Writing and Literacy in Chinese, Korean and Japanese. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 266. ISBN 9789027285768. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (11 July 1985). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. p. 330.

- Briggs, Asa and Burke, Peter (2002) A Social History of the Media: from Gutenberg to the Internet, Polity, Cambridge, pp.15–23, 61–73.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 911.

- Sohn, Pow-Key, "Early Korean Printing," Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 79, No. 2 (April -June , 1959), pp. 96–103 (103).

- Lane 1978, p. 33.

- Ikegami, Eiko (28 February 2005). Bonds of Civility: Aesthetic Networks and the Political Origins of Japanese Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521601153.

- Kotobank Saga Books. The Asahi Shimbun.

- 嵯峨本『伊勢物語』 (in Japanese). Printing Museum, Tokyo. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- Kazuo Mori (25 May 2017). 嵯峨本と角倉素庵。 (in Japanese). Letterpress Labo. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- Noriyuki Kasai. "About the Japanese and Composition, the reconstruction of history and future" (in Japanese). Japan Science and Technology Agency. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan: 1334–1615. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- History of printing. The Japan Federation of Printing Industries.

- Robertson, Frances, Print Culture: From Steam Press to Ebook, p.75, 2013, Routledge, ISBN 0415574161, 9780415574167, google books

- "Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu (FH.910.83-98)". University of Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- Sickman, L.; Soper, A. (1971). The Art and Architecture of China. Pelican History of Art (3rd ed.). Penguin. ISBN 0-14-056110-2.

Works cited

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7

- Bulliet, Richard W. (1987). "Medieval Arabic Tarsh: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Printing" (PDF). Journal of the American Oriental Society. 107 (3): 427–438. doi:10.2307/603463. JSTOR 603463. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Carter, John (2006). An ABC for Book Collectors (8th ed.). Delaware: Oak Knoll Books. ISBN 9781584561125.

- Chia, Lucille (2011), Knowledge and Text Production in an Age of Print: China, 900-1400, Brill

- Lane, Richard (1978). Images from the Floating World: The Japanese Print. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 978-1-56852-481-8. OCLC 475522764.

- McMurtrie, Douglas C. (1962), THE BOOK: The Story of Printing & Bookmaking, Oxford University Press, seventh edition

- Rivière, Jean Roger (1966). Summa Artis XX. El arte de la China (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985), Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 1: Paper and Printing, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08690-6

- Twitchett, Denis (1998b), The Cambridge History of China Volume 8 The Ming Dynasty, 1368—1644, Part 2, Cambridge University Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute

External links

- Centre for the History of the Book

- Excellent images and descriptions of examples, mostly Chinese, from the Schoyen Collection (Archived 11 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine)

- Fine example of a European block-book, Apocalypse, with hand-colouring

- Chinese book-binding methods, from the V&A Museum

- Chinese book-binding methods, from the International Dunhuang Project

- Chinese woodblock prints from SOAS University of London

- "Multiple Impressions: Contemporary Chinese Woodblock Prints" at the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- American Printing History Association—Numerous links to Online Resources and Other Organizations

- Wood-Block Printing, by F. Morley Fletcher, Illustrated by A. W. Seaby at Project Gutenberg

- Block printing in India

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on woodblock printing

- The History of Chinese Bookbinding: the case of Dunhuang findings

- Video: Block-printed wallpaper, a video demonstrating printing of multicolored wallpaper with a press, using blocks produced by William Morris