Propylaia (Acropolis of Athens)

The Propylaia (Greek: Προπύλαια, lit. 'Gates') is the classical Greek Doric building complex that functioned as the monumental ceremonial gateway to the Acropolis of Athens. Built between 437 and 432 BCE as a part of the Periklean Building Program, it was the last in a series of gatehouses built on the citadel. Its architect was Mnesikles, his only known building. It is evident from traces left on the extant building that the plan for the Propylaia evolved considerably during its construction, and that the project was ultimately abandoned in an unfinished state.

History

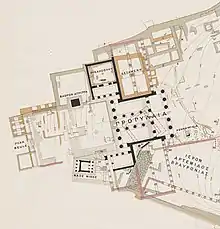

The approach to the Acropolis is determined by its geography. The only accessible pathway to the plateau lies between what is now the bastion of the Temple of Athena Nike and the terrace of the Agrippa Monument. In Mycenaean times the bastion (also referred to as the pyrgos or tower) was encased in a cyclopean wall, and amongst the few Mycenaean structures left in the archaeological record is a substantial wall on the terrace of the bastion that was part of the system of fortifications of the Acropolis.[2] This wall must have terminated at the first gateway, though opinions differ on the reconstruction of this earliest entrance.[3] At some point in the archaic period a ramp replaced the bedrock pathway; the buttress wall on the north side of the existing stairway is from this period.[4] This was followed shortly after Marathon by a programme of renovation on the Acropolis including the replacement of the gateway with a ceremonial entrance, usually referred to as the Older Propylon, and the refurbishment of the forecourt in front of it.[5] At this time, a section of the western Bronze Age wall, south of the gateway, received a marble lining on its western face and an integrated base at the northern extent for a perirrhanterion, or lustral basin. Bundgaard identified several remnants of this propylon and postulated a significant gatehouse situated between the Mycenaean wall and the archaic apsidal structure known as Building B.[6] What is evident, however, is that if the archaic gatehouse was not destroyed in the Persian attack of 480 then it must surely have been dismantled to facilitate the building works later in the century.[7]

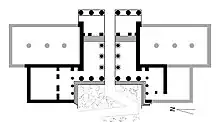

Mnesikles was appointed architect of the new propylon in 438.[8] From traces left in the construction of the final building it has been possible to reconstruct the development of the building plans during its construction. It was the practice of Greek builders to prepare for the bonding of joining walls, roof timber and other features in advance of the following phase of construction. From the socket for the roof beam and the spur walls on the north and south flanks of the central hall it can be discerned that the original plan was for a much larger building than its final form.[9] Mnesikles had planned a gatehouse composed of five halls: a central hall that would be the processional route to the Acropolis, two perpendicular flanking halls - north and south of the central hall - that would have spanned the whole width of the western end of the plateau, and two further, eastward projecting halls that were at 90 degrees to the north-south halls. Of these only the central hall, the north-east hall (the Pinakotheke) and a truncated version of the south-east hall reached completion. Furthermore, it is evident from the adaption of the stylobate that a stepped platform was added to the interior of the central hall such that the western-most tympanum and roof were raised above the rest of the building. The reasons for these alterations have been the cause of much speculation. They include practical considerations of the site,[10] religious objections to the displacement of the adjoining shrines,[11] and cost.[12] Whatever the reason it is clear that the project was abandoned in an unfinished state in 432 with the lifting bosses remaining and the surface of the ashlar blocks left undressed.

Alterations to the Propylaia in the classical period were slight,[14] the most significant being the construction of a monumental stairway in pentelic marble built in the reign of Claudius, probably 42 CE, and arranged as a straight flight of steps.[15] This included a central inclined plane along which the sacrificial animals could be led, also a small dog-leg stairway on the Nike bastion that led to the Temple of Athena Nike. This project was supervised by the Athenian Tib. Claudius Novius,[16] and is assumed to have been an Imperial benefaction from the great expense that must have been occurred.[17]

The Propylaia’s post-classical history sees it return to a military function beginning with the construction of the Buelé gate in the late third century CE,[18] perhaps associated with the refortification of Athens in the form of the Post-Herulian Wall.[19] Built from the dismantled elements of the Choragic Monument of Nikias this gate may have been in response to the Herulian invasions.[20] Sometime in the early Byzantine period the south wing was converted into a chapel. This conversion must not have taken place before the end of the sixth century, since in all other cases of ancient monuments being converted into Christian churches, there is no evidence of an earlier application of such a process.[21] The central section of the Propylaia was converted into a church in the tenth century CE when it was dedicated to the Taxiarches. The colonnade of the north-east wing was also walled off. In the same period, and specifically during the reign of Justinian, the large cistern between the north wing and the central building of the Propylaia was also constructed.[22] During the De la Roche era of occupation the complex was converted to a fortified residence similar in form to the crusader castles of the Levant by building the Rizokastro Wall, fortifying the Klepsydra, removing the entrance through the Beulé Gate, building the protective enclosure in front of the gate to the west of the south-west corner of the Nike Tower (now the only remaining entrance to the Acropolis) and also building the bastion between the Nike bastion and the Agrippa pedestal.[23] The Propylaia then served as Ducal Palace to the Acciaioli family, at which time the so-called Frankish Tower was built. In the main building, the central passage still served as the only means of entry to the interior of the Acropolis. It is almost certain that the spaces between the Doric and Ionic columns of the northern part of the west hall were blocked by, probably low, walls, limiting a space that would have served as an antechamber for the ruler's residence in the north wing.

Under the Tourkokratia the Propylaia served both as a powder magazine and battery emplacement and suffered significant damage as a result.[24] Only after the evacuation of the Turkish garrison could excavation and restoration work begin. From 1834 onwards the Medieval and Turkish additions to the Propylaia were demolished. By 1875 the Frankish Tower built on the south wing of the Propylaia was demolished, this marked the end of the clearing of the site of its post-classical accretions. The second major anastylosis since the early work of Pittakis and Rangavis was undertaken by engineer Nikolaos Balanos in 1909-1917.[25]

Architecture and sculpture

The Propylaia is approached from the west by means of the Beulé Gate, which as noted was a late Roman addition to the fortification of the citadel. Beyond this is the archaic ramp leading to the zig-zag Mnesiklean ramp that remains today. Immediately ahead is the U-shaped structure of the central hall and eastward wings. The central hall is a hexastyle Doric pronaos whose central intercolumniation is spaced one triglyph and one metope wider than the others. This central pathway, which leads through to the plateau, passes under a double row of Ionic columns the capitals of which are orientated north-south, and is axially parallel with the Parthenon. The westward-projecting wings are attached to the central hall by way of a tristyle in antis Doric colonnade of a scale two-thirds of that of the central hall. The crepidoma of the wings is in the canonical three-step form and in Pentelic marble, but the last course of the euthynteria below is in a contrasting blue Eleusian limestone. The orthostates of the two wings were also made of dark Eleusinian limestone, this visual continuity was maintained with the orthostates of the central hall and the top step on the interior flight of stairs all constructed in the same limestone.[26] The interior of the Central Hall is divided by a wall in which there are five doorways symmetrically arranged; the eponymous gates. The ceilings were supported by marble beams (about 6 m long) and the innermost squares of the coffers (Doric and Ionic coffers were both used) were decorated either with golden stars on a blue field with a bright green margin or an arrangement of palmettes.[27] The roofs were covered with Pentelic marble tiles. The building had some of the optical refinements of the Parthenon: inward inclination and entasis of the columns and curvature of the architrave.[28] However, the stylobate had no curvature. Some of its parts also shared the proportions with the Parthenon. For instance, the general ratio used was 3:7, very similar to the ratio of 4:9 used for the Parthenon.[29]

The building features no decorative or architectural sculpture; all metopes and pediments were left empty and there were no akroteria.[30] Nonetheless, a number of freestanding shrines and votives stood in the vicinity of the Propylaia, and have come to be associated with it if only by virtue of Pausanias' description of them and their proximity to the building. In the western precinct, there was the Hermes Propylaios by Alkamenes, which stood on the north end of the entrance.[31] Similarly, a relief of the Graces, made by Sokrates (the Boeotian sculptor active around 450 BCE), stood on the south of the entrance. In the east precinct, the bronze statue of Diotrephes, an Athenian general killed in combat in Boeotia during the Peloponnesian War, stood behind the second column from the south. The statue of Aphrodite made by Kalamis and dedicated by Kallias stood behind the second column from the north. The Leaina (an Archaic bronze lioness) stood near the north wall. A votive column carrying a young rooster probably stood along the south wall. A small shrine dedicated to Athena Hygieia was erected against the southernmost column on the eastern facade soon after 430 BCE.[32] Though accounts differ, this last shrine might have been erected to thank Athena for the end of the great plague.[33]

Pinakotheke

Pausanias records that the inner compartment of the north-east wing was used to display paintings; he calls it οἴκημα ἔχον γραφάς, “a chamber with paintings,”[34] and describes a number of works by masters of the fifth century. By Pausanias' time the picture gallery had been in existence for several centuries, so the Hellenistic historian Polemon of Ilion had written a, now lost, book entitled Περὶ τῶν ἐντοῖς Προπυλαίοις πινάκων (On the Panel Paintings in the Propylaia) which might have been an influence on the later writer.[35] Satyros, writing in the third century, described two panels dedicated by Alkibiades after his victories in the chariot race at Olympia and Nemea.[36] Also, a painting depicting Diomedes and Odysseus taking the Palladion from Troy, and the painting depicting Achilles on Skyros, painted by Polygnotos of Samos around 450 BCE. On the basis of these references, modern writers have frequently called the building the Pinakotheke, but there is no ancient authority for that epithet and no reason to believe the building was intended to be a picture gallery.

One particular problem posed by the northwest wing has been to explain the asymmetric placement of the doorway and windows in the front wall behind the colonnade.[37] It was John Travlos who first observed that in the placement of its door the chamber resembled Greek banqueting rooms, both the androns of private houses and the larger dining halls associated with sanctuaries.[38] His demonstration that seventeen dining couches could be placed end to end around the four walls of the room has become the consensus view, and the idea has been developed further to explain the intended function of the four subsidiary halls of the Propylaia in the original plan as banqueting facilities for the city’s high officials after the sacrifices at the Panathenaic festival.[39] Though this argument remains speculative.

Reception and influence

Despite being unfinished the Propylaia was admired in its own time. Demosthenes in his speech Against Androtion 23.13 describes the victors of Salamis as "the men who from the spoils of the barbarians built the Parthenon and Propylaia, and decorated the other temples, things in which we all take a natural pride." This revealing passage not only equates the Parthenon and gatehouse in significance but associates them with the heroic past.[41] His political rival Aeschines also made laudatory reference to the Propylaia when on the Pnyx he invited the demos to gaze on the gates and recall Salamis.[42] It wasn't only the object of approbation, however, Cicero in his De Officiis 2.60 (citing Demetrios of Phaleron) critiques the financial profligacy of the building.

The first documentary evidence of the Propylaia from the early modern period is Niccolò di Martoni's account of 1395 which indicated that the Buelé Gate was not in use at this point but the entrance to the Acropolis was still through the Propylaia. In the following centuries the only information on the building is from traveller's reports or the diaries of military officers. Attempts to survey the building begin in earnest in the late eighteenth century, notably J.-D. Le Roy's Ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Gréce 1758, and Stuart and Revett's The Antiquities of Athens 1762-1804, but are hampered by the spoilia and overbuilding on the structure. Subsequent studies include Bohn's fundamental work Die Propyläen der Akropolis zu Athen 1882 which summarized our knowledge of the building prior to the archaeological discoveries of 1885-1890; Bundgaard's Mnesicles, A Greek Architect at Work 1957 that examined the building's implications for planning practice; Dinsmoor Jr., The Propylaia I: The Predecessors 1980, careful study of the predecessors of the Propylaea. Since 1975? has been subject to ongoing restoration work under T. Tanoulas whose work has been published by the Acropolis Restoration Service as Μελέτη αποκαταστάσεως των Προπυλαίων (Study for the Restoration of the Propylaea) 1994.

Perhaps the two most notable examples of the Propylaia's architectural influence are the Greater Propylaia at Eleusis and Langhans's Brandenburg Gate of 1791. The former was a Roman Neo-Attic copy of the Central Hall at Athens from the late second century CE, probably instigated by Hadrian.[43] This was framed by two memorial arches in what was possibly a reference to the wings of the original building.[44] The latter, while an inexact copy, is clearly informed by the Athenian original likely drawing on Le Roy’s work, then the only reference source before the publication of The Antiquities of Athens. Commissioned by the King of Prussia the Gate inaugurated the Greek Revival in Germany even though the edifice deviated notably from the canonical Doric form; its frieze ends with a half-metope and its columns have bases.[45]

Notes

- P. Kavvadias, G. Kawerau, (1907). Die Ausgrabung der Akropolis vom Jahre 1885 bis zum Jahre 1890.

- Wright, 1994, p.325 lists the remains

- Wright, p.328

- E. Vanderpool, in Bradeen and McGregor, (eds.), Φορος, pp.159–160, argues that the ramp “de-militarized” the Acropolis and turned it from a fortress into a religious centre.

- Dinsmoor 1980, Eiteljorg 1993 doubts it

- Bundgaard, 1957, pp.55-63. Dinsmoor Jr, 1980, p.2 n.10 questioned whether Building B occupied this site at all.

- Shear, 2016, pp.273-274.

- Philochorus, FGrH 328 F 36, cited by Harpokration, s.v. προπύλαια ταῦτα (p 101 Keaney), the archon was Euthymenes (437/6)IG I3 462, line 3. Cf. also Heliodoros, FGrH 373 F 1, Plut. Per. 13.12.

- Shear, 2016, pp.278-279

- "perfect symmetry between the southwest and northwest wings would have required dismantling much of the still-impressive stretch of Cyclopean masonry south of the Propylaia", Hurwit, The Acropolis in the Age of Pericles, 2004, p.158

- W.B. Dinsmoor, The architecture of ancient Greece, Norton, 1975, pp.204-205. However recent scholarship questions whether the demos didn't supersede the priesthood, R. Parker, Athenian Religion, Oxford, 1996, pp-125-127.

- Shear, 2016, p.312 ff notes that the revolt of Potidaea in 432 could have changed the political climate against further building works. The Kallias Decrees, IG I3 52 434/3 BCE, appear to have already halted work on the Propylaia, J.M. Hurwit, The Athenian Acropolis, 1999, p.155.

- A. Trevor Hodge, "Bosses Reappraised," In Omni Pede Stare: Saggi Architettonici e circumvesuviani in memoriam Jos de Waele, 2005, Mols & Moormann, (eds.) disputes that this was their function.

- Some restoration work might have been done, Tanoulas, 1994, p.23. Also two brass equestrian groups were placed on the tops of the pilasters forming the western ends of the crest of each of the lateral wings. Stevens, Architectural Studies, pp.82-83.

- The final steps to the Propylaia might have been in the zigzag formation it has currently been restored as ("In 1956/7 Stikas replaced Pitakis' stairway with today's zig-zag ramp", The Acropolis Restoration News, 4, July 2004, p.15.) in the Mycenaean period. In the Classical period, it was probably a straight stairway, W.B. Dinsmoor Jr, 1982, p.18 n.3. See also Bundgaard, 1957, p.29.

- Inferred from IG II2 3271, II. 4-5

- Geoffrey C. R. Schmalz, Public Building and Civic Identity in Augustan and Julio-Claudian Athens, Ph.D diss. University of Michigan, 1994, p.203

- C.E. Beulé, L'Acropole d'Athènes, 1853, I, pp.100-106.

- A. Frantz, The Athenian Agora, vol. XXVI, Late Antiquity: AD 267-700, Princeton, 1988, Appendix.

- Tanoulas, 1994, p.26

- A. Frantz, 'From Paganism to Christianity in the Temples of Athens', Dumbarton Oaks Papers 19, 1965, p.204

- Tanoulas, 1994, p.29.

- Tanoulas, 1994, p.31.

- Including a lightning strike in 1640 that destroyed part of the roof, Tanoulas, 1994, p.33

- Tanoulas, 1994, p.33-36.

- R.F. Rhodes, Architecture and Meaning on the Athenian Acropolis, Cambridge, 1995, p.72 argues the colour scheme signifies the continuity of the Sacred Way.

- Dinsmoor (ed), 2004, p.256.

- L. Haselberger, Bending the Truth: Curvature and Other Refinements of the Parthenon, in J. Neils (ed), The Parthenon: From Antiquity to the Present, Cambridge, 2005, pp.133-136

- Dinsmoor (ed), 2004, pp.93-119.

- W.B. Dinsmoor, The architecture of ancient Greece, Norton, 1950, p.201 asserts, but doesn't demonstrate, that these were prepared.

- F. Chamoux, Hermès Propylaios, Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 141(1), 1996, pp.37-55.

- Of which the dedicatory base survives, IG I3 506; DAA 166, the only material evidence of the otherwise now lost sculptures.

- Catherine M. Keesling, Misunderstood Gestures: Iconatrophy and the Reception of Greek Sculpture in the Roman Imperial Period, Classical Antiquity, 2005, 24 (1): pp.41–79.

- 1.22.6

- Muller, FHG III, frag. 78, 260.

- Quoted in Athenaios 534d-e.

- Shear, 2016, p.293 n.65 lists the various theories.

- Travlos, 1971, p.482.

- P. Hellström, The planned function of the Mnesiklean Propylaia, OpAth 17, 1988, pp.107–121.

- J. Stuart, N. Revett. The Antiquities of Athens, vol. II, Ch.5 pl.1, 1787.

- D. Castriota, Myth, Ethos, and Actuality: Official Art in Fifth-century B.C. Athens, p.135 n.6. It is also, of course, historically inaccurate.

- 2.74-77. He also quoted the Theban general Epaminondas' wish to drag the gates off to the Cadmeia in Thebes.

- D. Giraud, Η κυρία είσοδος του ιερού της Ελευσίνος, 1991.

- Margaret M. Miles, The Roman Propylon in the City Eleusinion, in Architecture of the sacred, Bonna D. Wescoat and Robert G. Ousterhout (eds.), Cambridge, 2012, p.128.

- D.Watkin, German architecture and the classical ideal, MIT, 1987, p.62.

Bibliography

- Bohn, R. (1882). Die Propylaeen der Akropolis zu Athen. Berlin: Spemann. doi:10.11588/diglit.675.

- Bundgaard, J.A. (1957). Mnesicles, A Greek Architect at Work. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Bundgaard, J.A. (1974). The Excavation at the Athenian Acropolis 1882-1890. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- De Waele, J. (1990). The Propylaea of the Akropolis in Athens. The Project of Mnesikles. Amsterdam: J C Gieben.

- Dinsmoor, W.B. (1910). "The Gables of the Propylaea at Athens". American Journal of Archaeology. 14 (2): 143–184. doi:10.2307/496827. JSTOR 496827. S2CID 245265318.

- Dinsmoor, W.B. (1950). The Architecture of Ancient Greece. London: B. T. Batsford.

- Dinsmoor Jr., W.B. (1980). The Propylaia I: The Predecessors. Princeton.

- Dinsmoor Jr., W.B. (1982). "The asymmetry of the Pinakotheke - for the last a time?". Studies in Athenian Architecture, Sculpture, and Topography Presented to Homer A. Thompson. Hesperia Suppl.

- Dinsmoor Jr., W.B. (1984). "Preliminary Planning of the Propylaia by Mnesicles". Le dessin d'architecture dans les sociétés antiques. Actes du Colloque de Strasbourg 26-29 Janvier 1984.

- Dinsmoor, William B. & Dinsmoor Jr., William B. (2004). Dinsmoor, Anastasia Norre (ed.). The Propylaia to the Athenian Akropolis II: The Classical Building. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

- Eiteljorg II, Harrison (1993). The Entrance to the Acropolis Before Mnesicles.

- Frantz, A. (1988). The Athenian Agora XXIV, Late Antiquity A.D. 267-700. American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

- Kavvadias, P.; Kawerau, G. (1907). Die Ausgrabung der Akropolis vom Jahre 1885 bis zum Jahre 1890.

- Paga, J. (2021). Building democracy in late archaic Athens. Oxford.

- Shear, Ione Mylonas (1999). "The Western Approach to the Athenian Akropolis". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 119: 86–127. doi:10.2307/632313. JSTOR 632313.

- Shear Jr., T. Leslie (2016). Trophies of Victory: Public Building in Periklean Athens. Princeton.

- Stevens, G.Ρ. (1936). "The Periclean Entrance Court of the Acropolis of Athens". Hesperia. 5 (4): 443–520. doi:10.2307/146607. JSTOR 146607.

- Stevens, G.Ρ. (1946). "Architectural Studies Concerning the Acropolis of Athens". Hesperia. 15 (2): 73–106. doi:10.2307/146883. JSTOR 146883.

- Tanoulas, T. (1987). "The Propylaea of the Acropolis at Athens since the seventeenth century". Jahrbuch des deutschen archäologishen Instituts. 102.

- Tanoulas, T.; Ioannidou, M.; Moraitou, A. (1994). Μελέτη αποκαταστάσεως των Προπυλαίων. Athens.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Tanoulas, T. (1997). "Τα Προπύλαια της Αθηναϊκής Ακρόπολης κατά τον Μεσαιώνα". Βιβλιοθηκη Της Εν Αθηνας Αρχαιολογικης Εταιρειας. Archaeological Society at Athens (165).

- Travlos, J. (1971). Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Wright, James C. (1994). "The Mycenaean Entrance System at the West end of the Akropolis of Athens". Hesperia. 63 (3): 323–360. doi:10.2307/148295. JSTOR 148295.

.jpg.webp)