Protestant work ethic

The Protestant work ethic,[1] also known as the Calvinist work ethic[2] or the Puritan work ethic,[3] is a work ethic concept in scholarly sociology, economics, and historiography. It emphasizes that diligence, discipline, and frugality[4] are a result of a person's subscription to the values espoused by the Protestant faith, particularly Calvinism.

The phrase was initially coined in 1905 by Max Weber in his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.[5] Weber asserted that Protestant ethics and values, along with the Calvinist doctrines of asceticism and predestination, enabled the rise and spread of capitalism.[6] It is one of the most influential and cited books in sociology, although the thesis presented has been controversial since its release. In opposition to Weber, historians such as Fernand Braudel and Hugh Trevor-Roper assert that the Protestant work ethic did not create capitalism and that capitalism developed in pre-Reformation Catholic communities. Just as priests and caring professionals are deemed to have a vocation (or "calling" from God) for their work, according to the Protestant work ethic the "lowly" workman also has a noble vocation which he can fulfill through dedication to his work.

The concept is often credited with helping to define the societies of Northern, Central and Northwestern Europe as well as the United States of America.[7][8]

Basis in Protestant theology

Protestants, beginning with Martin Luther, conceptualized worldly work as a duty which benefits both the individual and society as a whole.[9] Thus, the Catholic idea of good works[10] was transformed into an obligation to consistently work diligently as a sign of grace. Whereas Catholicism teaches that good works are required of Catholics as a necessary manifestation of the faith they received, and that faith apart from works is dead and barren, the Calvinist theologians taught that only those who were predestined to be saved would be saved.[11]

For Protestants, salvation is a gift from God; this is the Protestant distinction of sola gratia.[12] In light of salvation being a gift of grace, Protestants viewed work as stewardship given to them. Thus Protestants were not working in order to achieve salvation but viewed work as the means by which they could be a blessing to others. Hard work and frugality were thought to be two important applications of being a steward of what God had given them. Protestants were thus attracted to these qualities and strove to reach them.

There are many specific theological examples in the Bible that support Protestant theology. Old Testament examples abound, such as God's command in Exodus 20:8–10 to "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God."[13] Another passage from the Book of Proverbs in the Old Testament provides an example: "A little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to rest, and poverty will come upon you like a robber, and want like an armed man."[14]

The New Testament also provides many examples, such as the Parable of the Ten Minas in the Book of Luke.[15]

The Apostle Paul in 2 Thessalonians said "If anyone is not willing to work, let him not eat."[16]

Protestant theology shares its origins with other and older Judeo-Christian theologies, if for no other reason than it shares some of the same source documents.[17]

American political history

_(14780176584).jpg.webp)

The first permanent English Settlement in America in the 17th century, at Jamestown, was led by John Smith.[18] He trained the first English settlers to work at farming and fishing. These settlers were ill-equipped to survive in the English settlements in the early 1600's and were on the precipice of dying. John Smith emphasized the Protestant Work Ethic and helped propagate it by stating "He that will not work, shall not eat" which is a direct reference to 2 Thessalonians 3:10.[19] This policy is credited with helping the early colony survive and thrive in its relatively harsh environment.[20]

Writer Frank Chodorov argued that the Protestant ethic was long considered indispensable for American political figures:

There was a time, in these United States, when a candidate for public office could qualify with the electorate only by fixing his birthplace in or near the "log cabin". He may have acquired a competence, or even a fortune, since then, but it was in the tradition that he must have been born of poor parents and made his way up the ladder by sheer ability, self-reliance, and perseverance in the face of hardship. In short, he had to be "self made". The so-called Protestant Ethic then prevalent held that man was a sturdy and responsible individual, responsible to himself, his society, and his God. Anybody who could not measure up to that standard could not qualify for public office or even popular respect. One who was born "with a silver spoon in his mouth" might be envied, but he could not aspire to public acclaim; he had to live out his life in the seclusion of his own class.[21]

— Frank Chodorov, The Radical Rich

Support

Some support exists that the Protestant work ethic may be so ingrained in American culture that when it appears people may not recognize it.[22] This may be due to the fact that ethics may be difficult to measure.[23] Due to the history of Protestantism in the United States, it may be difficult to separate the successes of the country from the ethic that may have significantly contributed to propelling it.[24]

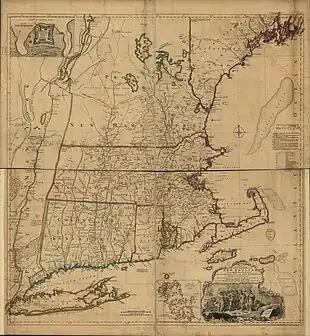

The original New England Colonies in 1677 were mostly Protestant in origin and thus were subject to the ethic.

There are some examples of scholarly work which support that the ethic has had a significant effect on some modern societies. Work at the University of Groningen supports this effect.[25] Other empirical research provides positive correlations as well.[26]

Recent scholarly work by Lawrence Harrison, Samuel P. Huntington, and David Landes has revitalized interest in Weber's thesis. In a New York Times article, published on June 8, 2003, Niall Ferguson pointed out that data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) seems to confirm that "the experience of Western Europe in the past quarter-century offers an unexpected confirmation of the Protestant ethic".[27]

Tshilidzi Marwala asserted in 2020 that the principles of Protestant ethic are important for development in Africa and that they should be secularized and used as an alternative to the ethic of Prosperity Christianity, which advocates miracles as a basis of development.[28]

In a recent journal article, Benjamin Kirby agrees that this influence of prosperity theology, particularly within neo-Pentecostal movements, complicates any attempt to draw parallels between, first, the relationship between contemporary Pentecostalism and neoliberal capitalism, and second, the relationship between Calvinistic asceticism and modern capitalism that interested Weber. Nevertheless, Kirby emphasises the enduring relevance of Weber's analysis: he proposes a "new elective affinity" between contemporary Pentecostalism and neoliberal capitalism, suggesting that neo-Pentecostal churches may act as vehicles for embedding neoliberal economic processes, for instance by encouraging practitioners to become entrepreneurial, responsibilised citizens.[29]

Criticism

Joseph Schumpeter argued that capitalism began in Italy in the 14th century, not in the Protestant areas of Europe.[30] Other factors that further developed the European market economy included the strengthening of property rights and lowering of transaction costs with the decline and monetization of feudalism, and the increase in real wages following the epidemics of bubonic plague.[31]

Economists Sascha Becker and Ludger Wößmann have posited an alternate theory, claiming that the literacy gap between Protestants (as a result of the Reformation) and Catholics was sufficient explanation for the economic gaps, and that the "results hold when we exploit the initial concentric dispersion of the Reformation to use distance to Wittenberg as an instrument for Protestantism".[32] However, they also note that, between Luther (1500) and Prussia during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), the limited data available has meant that the period in question is regarded as a "black box" and that only "some cursory discussion and analysis" is possible.[33]

Historian Fernand Braudel wrote that "all historians" opposed the "tenuous theory" of Protestant ethic, despite not being able to entirely quash the theory "once and for all". Braudel continues to remark that the "northern countries took over the place that earlier had been so long and brilliantly been occupied by the old capitalist centers of the Mediterranean. They invented nothing, either in technology or business management".[34]

Social scientist Rodney Stark commented that "during their critical period of economic development, these northern centers of capitalism were Catholic, not Protestant", with the Reformation still far off in the future. Furthermore, he also highlighted the conclusions of other historians, noting that, compared to Catholics, Protestants were "not more likely to hold the high-status capitalist positions", that Catholic Europe did not lag in its industrial development compared to Protestant areas, and that even Weber wrote that "fully developed capitalism had appeared in Europe" long before the Reformation.[35] As British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper stated, the concept that "large-scale industrial capitalism was ideologically impossible before the Reformation is exploded by the simple fact that it existed".[36]

Andersen et al found that the location of monasteries of the Catholic Order of Cistercians, and specifically their density, highly correlated to this work ethic in later centuries;[37] ninety percent of these monasteries were founded before the year 1300 AD. Joseph Henrich found that this correlation extends right up to the twenty-first century.[38]

Pastor John Starke writes that the Protestant work ethic "multiplied myths about Protestantism, Calvinism, vocation, and capitalism. To this day, many believe Protestants work hard so as to build evidence for salvation."[39] Others have connected the concept of a Protestant work ethic to racist ideals.[40][41] Civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. said:

We have deluded ourselves into believing the myth that capitalism grew and prospered out of the Protestant ethic of hard work and sacrifice. The fact is that capitalism was built on the exploitation and suffering of black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor—both black and white, here and abroad.[42]

A 2021 study argues that the values represented by the Protestant ethic as developed by Max Weber are not exclusively related to Protestantism but to the modernization phase of economic development. Weber observed this phase of development in areas dominated by Protestants at the time of his observations. From these observations, he concludes that a worldly asceticism consisting of a preference for work and a sober life are associated with Protestantism. Economists Annemiek Schilpzand and Eelke de Jong argue that this value pattern is associated with the modernization phase of a region’s economic development and thus, in principle, can be found for any religion or for non-religious persons.[43]

See also

- Achievement ideology

- Anglo-Saxon economy

- Critical responses to Weber

- Critique of work

- God helps those who help themselves – Religious saying

- Imperial German influence on Republican Chile

- Industrial Revolution

- Laziness

- Merton thesis

- Pray and work

- Predestination in Calvinism

- Prosperity theology – Material wealth-based Christian belief

- Prussian virtues

- Refusal of work

- Sloth (deadly sin)

- Underclass

Notes

References

- Gini, Al (2018). "Protestant Work Ethic". The SAGE Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society: 2791–2793. doi:10.4135/9781483381503. ISBN 9781483381527.

- The Idea of Work in Europe from Antiquity to Modern Times by Catharina Lis

- Ryken, Leland (2010). Worldly Saints: The Puritans As They Really Were. Harper Collins. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-0-310-87428-7.

- "Protestant Ethic". Believe: Religious Information Source.

- Weber, Max (2003) [First published 1905]. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Parsons, Talcott. New York: Dover. ISBN 9780486122373.

- "Weber, Calvinism and the Spirit of Modern…". tutor2u. March 22, 2020.

- Ward, Charles (September 1, 2007). "Protestant work ethic that took root in faith is now ingrained in our culture". Houston Chronicle.

- Luzer, Daniel (September 4, 2013). "The Protestant Work Ethic is Real". Pacific Standard.

- "How Martin Luther gave us the roots of the Protestant work ethic". November 2017.

- "Are Good Works Necessary for Salvation?".

- "Predestination Calvinism | Cru Singapore".

- "Sola Gratia". June 13, 2016.

- "Bible Gateway passage: Exodus 20 – English Standard Version".

- "Proverbs 6:6–11 ESV – Bible Gateway".

- "Luke 19:11–27 ESV – Bible Gateway".

- "2 Thessalonians 3:6–12 ESV – Bible Gateway".

- "Jewish and Christian Bibles: Comparative Chart".

- "John Smith (bap. 1580–1631)". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- "2 Thessalonians 3:10 ESV – Bible Gateway".

- "John Smith, Jamestown and the Roots of America". YouTube.

- Chodorov, Frank (21 March 2011). "The Radical Rich". Mises Daily Articles. Mises Institute.

- "Protestant work ethic that took root in faith is now ingrained in our culture". September 2007.

- "Why Ethics is Hard | Psychology Today".

- "Protestantism in America".

- O'Connell, Andrew (August 29, 2013). "There Really is Such a Thing as the Protestant Work Ethic". Harvard Business Review.

- Jones, Harold B. (July 1997). "The Protestant Ethic: Weber's Model and the Empirical Literature". Human Relations. 50 (7): 757–778. doi:10.1177/001872679705000701. S2CID 146171646.

- Ferguson, Niall (June 8, 2003). "The World; Why America Outpaces Europe (Clue: The God Factor)". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- Marwala, Tscilidzi (November 29, 2020). "A Protestant work ethic, and not the flash and glamour of Prosperity Christianity, is what Africa needs". Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- Kirby, Benjamin (2019). "Pentecostalism, economics, capitalism: Putting the Protestant Ethic to work". Religion. 49 (4): 571–591. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2019.1573767. S2CID 182190916.

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1994), "Part II From the Beginning to the First Classical Situation (to about 1790), chapter 2 The scholastic Doctors and the Philosophers of Natural Law", History of Economic Analysis, Routledge, pp. 74–75, ISBN 978-0-415-10888-1, OCLC 269819. In the footnote, Schumpeter refers to Usher, Abbott Payson (1943). The Early History of Deposit Banking in Mediterranean Europe. Harvard economic studies; v. 75. Harvard university press. and de Roover, Raymond (December 1942). "Money, Banking, and Credit in Medieval Bruges". Journal of Economic History. 2, supplement S1: 52–65. doi:10.1017/S0022050700083431. S2CID 154125596.

- Voigtlander, Nico; Voth, Hans-Joachim (October 9, 2012). "The Three Horsemen of Riches: Plague, War, and Urbanization in Early Modern Europe" (PDF). The Review of Economic Studies. 80 (2): 774–811. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.303.2638. doi:10.1093/restud/rds034. hdl:10230/778.

- Becker, Sascha O.; Woessmann, Ludger (May 2009). "Was Weber Wrong? A Human Capital Theory of Protestant Economic History *". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 124 (2): 531–596. doi:10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.531. hdl:1893/1653. ISSN 0033-5533. S2CID 3113486.

- Becker, Wossmann (2007), p. A5, Appendix B

- Braudel, Fernand (1977). Afterthoughts on Material Civilization and Capitalism Material Civilization and Capitalism. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- "Protestant Modernity".

- Trevor-Roper. 2001. The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century. Liberty Fund

- Andersen, Thomas Barnebeck; Bentzen, Jeanet; Dalgaard, Carl‐Johan; Sharp, Paul (September 2017). "Pre‐Reformation Roots of the Protestant Ethic". The Economic Journal. 127 (604): 1756–1793. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12367. S2CID 153784078.

- Henrich, Joseph (2020). The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374173227.

- Starke, John (16 June 2017). "The Myth of the Protestant Work Ethic".

- Rosenthal, L. (2011). "Protestant work ethic's relation to intergroup and policy attitudes: A meta-analytic review | Semantic Scholar". European Journal of Social Psychology. 41 (7): 874–885. doi:10.1002/EJSP.832. S2CID 33949400.

- Massey, Alana (May 26, 2015). "The White Protestant Roots of American Racism". The New Republic.

- "Smiley: Capitalism has always been built on the back of the poor — both black and white". Public Radio International.

- Schilpzand, Annemiek; de Jong, Eelke (2021). "Work ethic and economic development: An investigation into Weber's thesis". European Journal of Political Economy. 66: 101958. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2020.101958.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

Further reading

- Anderson, Elizabeth (2023). "The Dual Nature of the Protestant Work Ethic and the Birth of Utilitarianism". Hijacked: How Neoliberalism Turned the Work Ethic against Workers and How Workers Can Take It Back. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1009275439.

- Sascha O. Becker and Ludger Wossmann. "Was Weber Wrong? A Human Capital Theory of Protestant Economics History". Munich Discussion Paper No. 2007-7, January 22, 2007.

- Frey, Donald (August 14, 2001), "Protestant Ethic Thesis", in Robert Whaples (ed.), EH.Net Encyclopedia, archived from the original on March 28, 2014

- Robert Green, editor. The Weber Thesis Controversy. D.C. Heath, 1973, covers some of the criticism of Weber's theory.

- Hill, Roger B. (1992), Historical Context of the Work Ethic, archived from the original on August 17, 2012

- Haller, William. "Milton and the Protestant Ethic." Journal of British Studies 1.1 (1961): 52–57 [www.jstor.org/stable/175098 online].

- McKinnon, Andrew (2010). "Elective affinities of the Protestant ethic: Weber and the chemistry of capitalism" (PDF). Sociological Theory. 28 (1): 108–126. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01367.x. hdl:2164/3035. S2CID 144579790.

- Max Weber. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Charles Scribner's sons, 1959.

- Van Hoorn, André; Maseland, Robbert (2013). "Does a Protestant work ethic exist? Evidence from the well-being effect of unemployment". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 91 (2013): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2013.03.038. ISSN 0167-2681.

External links

| Library resources about Protestant work ethic |

![]() Quotations related to Protestant work ethic at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Protestant work ethic at Wikiquote