Proteus (2003 film)

Proteus is a 2003 romantic drama film by Canadian director John Greyson. The film, based on an early 18th century court record from Cape Town, explores the romantic relationship between two prisoners, one black (Khoikhoi) and one Dutch-born white, at Robben Island in South Africa in the 18th century.[1][2]

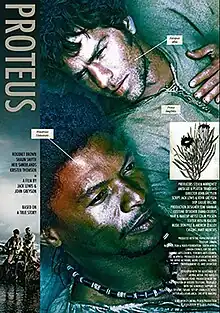

| Proteus | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | John Greyson |

| Written by | John Greyson Jack Lewis |

| Produced by | Anita Lee Steven Markovitz Platon Trakoshis Damon D'Oliveira John Greyson Jack Lewis |

| Cinematography | Giulio Biccari |

| Edited by | Roslyn Kalloo |

| Music by | Don Pyle Andrew Zealley |

| Distributed by | Strand Releasing |

Release date | 2003 |

Running time | 100 mins |

| Countries | Canada South Africa |

| Languages | Khoikhoi, English, Afrikaans, Dutch |

Although the film premiered at the 2003 Toronto International Film Festival, it did not have a general theatrical release until 2005.

Plot

Set in 18th-century South Africa, the film dramatizes the true story of Claas Blank (Rouxnet Brown) and Rijkhaart Jacobsz (Neil Sandilands), two prisoners on Robben Island. Herder Claas Blank was serving 10 years for "insulting a Dutch citizen" and Rijkhaart was a Dutch sailor convicted of committing "unnatural acts" with another man. The two men, initially hostile to each other, form a secret relationship, using trips to a private water tank to bond. Their relationship had a racial component, as Jacobsz was a Dutchman, while Blank was a Khoi.

Virgil Niven (Shawn Smyth), a Scottish botanist, befriends Blank for his knowledge of South African flora, including the protea. It is suggested that he may have had a sexual interest in Blank.

In 1735, Blank and Jacobsz were executed for sodomy, by being drowned, after jealousy by other inmates caused problems within the jail.

The film ends with an extract from the speech Nelson Mandela made at his sentencing hearing in 1964, before he was imprisoned on Robben Island.[3]

Analysis

The film explores unanswered questions, such as why prison officials tolerated the relationship for a full decade before Blank and Jacobsz were executed. In an interview packaged with the DVD release, John Greyson notes the real Blank and Jacobsz began their relationship when they were both teenagers—Blank having been imprisoned on Robben Island at age 16—and were actually known to be a couple for twenty years before they were charged with sodomy and executed, when they were both nearly 40.

Intentional anachronisms, such as transistor radios, electric typewriters and jeeps, are used in the film to illustrate Greyson's larger theme that homophobia and racism of the type that led to Blank's and Jacobsz' executions remain very much present in the world. These twentieth-century objects, including contemporary (c. 1964) dress on many occasions, appear in juxtaposition with eighteenth-century items. The eighteenth-century prison commandant, for example, is replaced by a former subordinate who wears a twentieth-century guard's uniform and is often accompanied by a fierce-looking Alsatian on a short lead.[3] A wet bag, a torture devise from Apartheid South Africa, is seen.[3]

Cast

- Rouxnet Brown as Claas Blank

- Shaun Smyth as Virgil Niven

- Neil Sandilands as Rijkhaart Jacobz

- Kristen Thomson as Kate

- Tessa Jubber as Elize

- Terry Norton as Betsy

- Adrienne Pearce as Tinnie

- Grant Swanby as Willer

- Brett Goldin as Lourens

- A.J. van der Merwe as Settler

- Deon Lotz as Governor

- Jeroen Kranenburg as Scholz

- Andre Samuels as Nanseb

- Johan Jacobs as Nama Prisoner

- Katrina Kaffer as Kaness

- Kwanda Malunga as Claas (when age 10)

- Illias Moseko as Claas's Grandfather

- Andre Lindveldt as Minstrel

- Peter van Heerden as Soldier

- Jane Rademeyer as Niven's Wife

- Andre Odendaal as Floris

- Lola Dollimore as Niven's Daughter

- Robin Smith as Munster

- Colin le Roux as Hendrik

- Andre Rousseau as De Mepesche

- Edwin Angless as Hangman

Reception

Dennis Harvey of Variety stated that the "film has enough erotic and exotic content to win arthouse viewers" but it "lacks lush aesthetics and impassioned complexity, ending up a tad remote".[4]

Giving the film 3 out of 4 stars, Ken Fox of TV Guide said "the postmodern touches never detract from what is at heart a deeply moving love story".[5]

Dave Kehr of The New York Times stated "a heavy, pretentious, and derivative film" and it had been "gussied it up with fantasy sequences and formal games that distract from the dramatic core".[6]

References

- Ben-Asher, Noa (15 December 2005). "Screening Historical Sexualities: A Roundtable on Sodomy, South Africa, and Proteus (with Brassel, Garrett, Greyson, Lewis, Newton-King)". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 11 (3): 437–455. doi:10.1215/10642684-11-3-437. S2CID 145313359. SSRN 1316545.

- Michelle MacArthur, Lydia Wilkinson and Keren Zaiontz (eds.) Performing Adaptations: Essays and Conversations on the Theory and Practice of Adaption, p. 190, at Google Books

- Gary M. Kramer Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews, p. 36, at Google Books

- Harvey, Dennis (15 September 2003). "Proteus". Variety. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Fox, Ken. "Proteus, TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Kehr, Dave (30 July 2004). "FILM IN REVIEW; 'Proteus'". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2018.