Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh

The Archdiocese of Armagh (Latin: Archidioecesis Ardmachana; Irish: Ard-Deoise Ard Mhacha) is a Latin ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church located in the northern part of Ireland. The ordinary is the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh who is also the Metropolitan of the Ecclesiastical province of Armagh and the Primate of All Ireland. The mother church is St Patrick's Cathedral. The claim of the archdiocese to pre-eminence in Ireland as the primatial see rests upon its traditional establishment by Saint Patrick circa 445. It was recognised as a metropolitan province in 1152 by the Synod of Kells.

Archdiocese of Armagh Archidioecesis Armachana Ard-Deoise Ard Mhacha | |

|---|---|

St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Armagh | |

| Location | |

| Country | Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland |

| Territory | County Louth, most of County Armagh and parts of counties Tyrone, Londonderry and Meath |

| Ecclesiastical province | Armagh |

| Coordinates | 54.348°N 6.656°W |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 3,472 km2 (1,341 sq mi) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2018) 348,000 242,860 (69.8%) |

| Parishes | 61 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | 445 (As Diocese) 1152 (As Archdiocese) |

| Cathedral | St Patrick's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Armagh |

| Patron saint | |

| Secular priests | 138 |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Archbishop | Eamon Martin |

| Auxiliary Bishops | Michael Router |

| Vicar General |

|

| Bishops emeritus | Seán Brady |

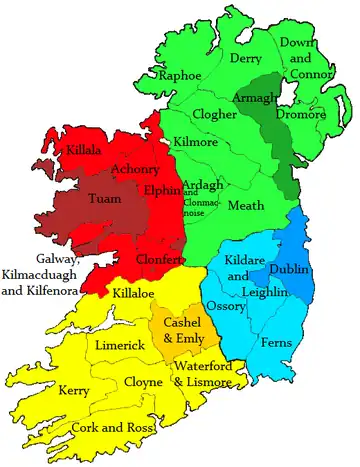

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| armagharchdiocese.org | |

As of September 2014 the incumbent Archbishop is Eamon Martin. He has been assisted since 2019 by Michael Router, who is currently the only Catholic auxiliary bishop in Ireland.

Province and geographic remit

The Province of Armagh is one of the four ecclesiastical provinces that together form the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland; the others are Dublin, Tuam and Cashel. The geographical remit of the province straddles both political jurisdictions on the island of Ireland – the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. In Northern Ireland, the remit covers parts of the former administrative counties of Armagh, Londonderry and Tyrone. In the Republic of Ireland, the remit covers parts of County Louth and most of County Meath. It contains the city of Armagh and the large towns Ardee, Coalisland, Drogheda, Dundalk, Dungannon and Magherafelt.

The suffragan dioceses of the Metropolitan Province are:

Ecclesiastical history

Foundation and early history

St. Patrick, having received some grants of land from the chieftain Daire, on the hill called Ard-Macha (the Height of Macha), built a stone church on the summit and a monastery and some other religious edifices and fixed on this place for his metropolitan see. He also founded a school in the same place, which soon became famous and attracted thousands of scholars. In the course of time other religious bodies settled in Armagh, such as the Culdees, who built a monastery there in the 8th century.

The city of Armagh was thus until modern times a purely ecclesiastical establishment. About 448, St. Patrick, aided by Secundinus and Auxilius, two of his disciples, held a synod at Armagh, of which some of the canons are still extant. One of these expressly mentions that all difficult cases of conscience should be referred to the judgment of the Archbishop of Armagh, and that if too difficult to be disposed of by him with his counsellors they should be passed on to the Apostolic See of Rome. In Irish times, the primacy of Armagh was questioned only by the great southern centre of the Irish Church, at Cashel.

For many centuries the primates were accustomed to make circuits and visitations through various parts of the country for the collection of their dues. This was called the "Cattlecess", or the "Law of St. Patrick". Beginning in 734, during the incumbency of Primate Congus, it continued until long after the Cambro-Norman invasion, but ceased as soon as Norman prelates succeeded to the see. Two kings gave it their royal sanction: Felim, King of Munster, in 822, and Brian Boru, in 1006. The record of the latter's sanction is preserved in the Book of Armagh, in the handwriting of Brian Boru's chaplain. To add solemnity to their collecting tours, the primates were in the habit of carrying with them the shrine of St. Patrick, and as a rule their success was certain. These collections seem to have been made at irregular intervals and were probably for the purpose of keeping up the famous school of Armagh, said at one time to contain 7,000 students, as well as for the restoration, often needed, of the church and other ecclesiastical buildings when destroyed by fire or plundered in war. The Irish annals record no fewer than seventeen burnings of the city, either partial or total. It was plundered on numerous occasions by the Danes and the clergy driven out of it. It was also sacked during the conquest of Ulster by the Cambro-Normans.

Disputes over primacy

The seizure of the primacy of Armagh by laymen in the 11th century has received great prominence owing to St. Bernard's denunciation of it in his "Life of St. Malachy", but the abuse was not without a parallel on the continent of Europe. The chiefs of the tribe in whose territory Armagh stood usurped the position and temporal emoluments of the primacy and discharged by deputy the ecclesiastical functions. The abuse continued for eight generations until Cellach, known as St. Celsus (1105–29), who was intruded as a layman, had himself consecrated bishop, and ruled the see with great wisdom.

In 1111 he held a great synod at Fiadh-Mic-Aengus at which were present fifty bishops, 300 priests, and 3,000 other ecclesiastics, and also Murrough O'Brian, King of Southern Ireland, and his nobles. During his incumbency the priory of Sts. Peter and Paul at Armagh was re-founded by Imar, the learned preceptor of St. Malachy. This was the first establishment in Ireland into which the Canons Regular of St. Augustine had been introduced. Rory O'Connor, High King of Ireland, afterwards granted it an annual pension for a public school.

After a short interval, Celsus was succeeded by St. Malachy O'Morgair (1134–37), who later suffered many tribulations in trying to effect a reformation in the diocese. He resigned the see after three years and retired to the Bishopric of Down. In 1139 he went to Rome and solicited the Pope for two palliums, one for the See of Armagh and the other probably for a new Metropolitan See of Cashel. The following year he introduced the Cistercian Order into Ireland, by the advice of St. Bernard. He died at Clairvaux, while making a second journey to Rome. St. Malachy is honoured as the patron saint of the diocese.

Gelasius succeeded him and during a long incumbency of thirty-seven years held many important synods which effected great reforms. At the Synod of Kells, held in 1152 and presided over by Cardinal Paparo, the Pope's legate Gelasius received the pallium and at the same time three others were handed over to the new metropolitan sees of Dublin, Cashel, and Tuam.

The successor of Gelasius in the see, Cornelius Mac Concaille, who died at Chambéry the following year, on a journey to Rome, has been venerated ever since in that locality as a saint. He was succeeded by Gilbert O'Caran (1175–80), during whose incumbency the see suffered greatly from the depredations of the Anglo-Norman invaders. William Fitz-Aldelm pillaged Armagh and carried away St. Patrick's crosier, called the "Staff of Jesus". O'Caran's successor was Thomas O'Connor (1181–1201). In the year after his succession to the see, Pope Lucius III, at the instance of John Comyn, the first English prelate in the See of Dublin, tried to abolish the old Irish custom according to which the primates claimed the right of making solemn circuits and visitations in the province of Leinster as well as those of Tuam and Munster. The papal bull issued was to the effect that no archbishop or bishop should hold any assembly or ecclesiastical court in the Diocese of Dublin, or treat of the ecclesiastical causes and affairs of the said diocese, without the consent of the Archbishop of Dublin, if the latter were actually in his see, unless specially authorised by the Papal See or the Apostolic legate. This Bull laid the groundwork of a bitter and protracted controversy between the Archbishops of Armagh and of Dublin, concerning the primatial right of the former to have his cross carried before him and to try ecclesiastical cases in the diocese of the latter. This contest, however, must not be confounded with that regarding the primacy, which did not arise until the 17th century.

Lordship of Ireland (1215–1539)

As the first Anglo-Norman adventurers who came to Ireland showed very little scruple in despoiling the churches and monasteries, Armagh suffered considerably from their depredations. When the English kings got a footing in the country, they began to intervene in the election of bishops and a contest arose between King John and Pope Innocent III regarding Eugene MacGillaweer, elected to the primatial see in 1203. This prelate was present at the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215 and died at Rome the following year. The English kings also began to claim possession of the temporalities of the sees during vacancies and to insist on the newly elected bishops suing them humbly for their restitution.

Primate Reginald (1247–56), a Dominican, obtained a papal brief uniting the county of Louth to the See of Armagh. Primate Patrick O'Scanlan (1261–70), also a Dominican, rebuilt to a large extent the cathedral of Armagh and founded a house for Franciscans in that city. Primate Nicholas MacMaelisu (1272–1302) convened an important assembly of the bishops and clergy of Ireland at Tuam in 1291, at which they bound themselves by solemn oaths to resist the encroachments of the secular power. Primate Richard Fitz-Ralph (1346–60) contended publicly both in Ireland and England with the Mendicant Orders on the question of their vows and privileges.

A contest regarding the primacy of Armagh was carried on intermittently during these centuries by the Archbishops of Dublin and Cashel, especially the former, as the city of Dublin was the civic metropolis of the kingdom. During the English period, the primates rarely visited the city of Armagh, preferring to reside at the arch-episcopal manors of Dromiskin and Termonfechan, in the county of Louth, which was within the Pale. During the reign of Henry VIII, Primate Cromer, being suspected of heresy by the Holy See, was deposed in favour of Robert Wauchope (1539–51), a distinguished theologian, who assisted at the Council of Trent. In the meantime, George Dowdall, a zealous supporter of Henry, had been elevated into the Church of Ireland See of Armagh by that monarch, but upon the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer in the reign of Edward VI, he left Ireland in disgust. In the beginning of the reign of Queen Mary I, Dowdall (1553–58) was appointed properly by the Pope on account of the great zeal he had shown against Protestantism. He survived his consecration only three months.

During the English Reformation

After the short incumbency of Donagh O'Tighe (1560–62), the see was filled by Richard Creagh (1564–85), a native of Limerick. He was lawfully arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was judicially examined and left to languish in captivity for some years until his death. Edward MacGauran, who succeeded him (1587–94), was very active in soliciting aid from the pope and Philip II of Spain for the Irish who were then engaged in a struggle with the Crown. After an interval of eight years, MacGauran was succeeded by Peter Lombard (1601–25) (not to be confused with Peter Lombard, the medieval Bishop of Paris). He remained in exile, in Rome, during the whole twenty-four years of his incumbency and thus never once visited his diocese.

Hugh MacCawell, a Franciscan, was consecrated abroad for the see in 1626, but died before he could reach it. Hugh O'Reilly, the next primate (1628–53), was very active in the political movements of his day. In the chaotic aftermath of the Irish Rebellion of 1641, in 1642, he summoned the Ulster bishops and clergy to a synod at Kells in which the war then carried on by the Irish was declared lawful and pious. He took a prominent part in the Irish Confederation of Kilkenny and was appointed a member of the Supreme Council of twenty-four persons who carried on the government of the country in the name of King Charles I. During the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–53), Ireland was re-conquered by English Parliamentarian forces, who were very hostile to Catholicism. After the defeat, death or exile of most of the Roman Catholic Irish leaders he was elected nominal commander of the Roman Catholic forces for the remainder of the conflict.

Edmund O'Reilly (1657–69) succeeded to the see, but owing to the difficulties of the time was only able to spend two years in the diocese out of the twelve of his incumbency. He was exiled on four occasions. During the whole time he spent in the diocese, he was hiding in woods and caves and never had any bed but a cloak thrown over straw. He opposed Peter Valesius Walsh, the author of the "Loyal Remonstrance" (1661, 1672) to King Charles II, and died in exile in France.

The next primate was Oliver Plunkett (1669–81). Shortly after his accession to the see, he was obliged to defend the primatial rights of Armagh against the claims put forward for Dublin by its archbishop, Peter Talbot. At a meeting of the Roman clergy in Dublin in 1670, each of these prelates refused to subscribe subsequent to the other. Plunkett thereupon wrote a work on the ancient rights and prerogatives of his see, published in 1672, under the title Jus Primatiale; or the ancient Preeminence of the See of Armagh above all the other Archbishops in the Kingdom of Ireland, asserted by O. A. T. H. P. Talbot replied to two years later in a dissertation styled Primatus Dublinensis; or the chief reasons on which the Church of Dublin relies in the possession and prosecution of her right to the Primacy of Ireland. A violent persecution stilled the controversy for some time and subsequent primates asserted their authority from time to time in Dublin.

In 1719 two Briefs of Pope Clement XI were in favour of the claims of Armagh. In practice, however, the primatial right has fallen into desuetude in Ireland as in every other part of the Church. In 1679, Oliver Plunkett was arrested on a charge of conspiring to bring 20,000 Frenchmen into the country and of having levied moneys on his clergy for the purpose of maintaining 70,000 men for an armed rebellion against the Crown. After being confined in Dublin Castle for many months, he was presented for trial on these and other charges in Dundalk; but the jury, though all Protestants, refused to find a true bill against him. The venue, however, of his trial was changed to London, where he was tried by a jury before he was able to gather his witnesses and bring them across, though he made the request to the judge. The principal witnesses against him were some priests and friars of Armagh whom he had censured and suspended for their alleged conduct. He was dragged on a sledge to Tyburn on 1 July 1681, where he was hanged, drawn, and quartered in presence of an immense multitude. His head, still in a good state of preservation, can be viewed to this day in St. Peter's church, West St., Drogheda.

Penal times

Dominic Maguire (1683–1707), a Dominican, succeeded to the see after the death of the Oliver Plunket. This primate, having to go into exile after the surrender of Limerick in 1691, spent the sixteen years that intervened between that time and his death in a very destitute condition. In the meantime the See of Armagh was administered by a vicar, Patrick Donnelly, a priest of the diocese, who in 1697 was appointed Bishop of Dromore, though retaining the administration of Armagh for several years afterwards.

Owing to the severity of the laws there was no primate resident in Ireland for twenty-three years after the flight of Primate Maguire, in 1691. Hugh MacMahon (1714–37), Bishop of Clogher, was at last appointed to the bereft see. Living during the worst of the penal times, the primate was obliged constantly to wander from place to place, saying Mass and administering Confirmation in the open air. Nevertheless, in spite of these difficulties he has left his name to posterity by the learned work Jus Primatiale Armacanum, written by command of the pope in defence of the primatial rights of Armagh. He was succeeded by his nephew, Bernard MacMahon (1737–47), then Bishop of Clogher, who is described as a prelate remarkable for zeal, charity, prudence, and sound doctrine. He also suffered considerably from the persecution, and spent most of his time in hiding. Bernard was succeeded in the primacy by his brother, Ross MacMahon (1747–48), also Bishop of Clogher.

Michael O'Reilly (1749–58), Bishop of Derry, was the next primate. He published two catechisms, one in Irish and the other in English, the latter of which has been in use in parts of the north of Ireland until our own time. On one occasion this primate and eighteen of his priests were arrested near Dundalk. He lived in a small thatched cottage at Milltown, in Termonfechin parish, and at times had to lie concealed in a narrow loft under the thatch. Anthony Blake (1758–86) was his successor. The persecution having subsided to a great extent, he was not harried like his predecessors, but nevertheless could not be induced to live permanently in his diocese, a circumstance which was the occasion of much discontent among his clergy and led to a temporary suspension from his duties. Richard O'Reilly (1787–1818) was his successor in the primacy. Having an independent fortune, he was the first Catholic prelate since the Revolution who was able to live in a manner becoming his station. By his gentleness and affability he succeeded in quieting the dissensions which had distracted the diocese during the time of his predecessor and was thenceforward known as the "Angel of Peace". In 1793, he laid the foundation-stone of Saint Peter's Church in Drogheda, which was to serve as his pro-cathedral, one of the first Catholic churches to be built within the walls of a town in Ireland since the Reformation. The Corporation of Drogheda, wearing their robes and carrying the mace and sword, appeared on the scene and forbade the ceremony to proceed, but their protest was disregarded.

19th and 20th centuries

Patrick Curtis (1819–32), who had been rector of the Irish College of Salamanca, was appointed to the see in more hopeful times, and lived to witness the emancipation of the Roman Church in the UK. He was one of the first to join the Catholic Association, and was on friendly terms with the Duke of Wellington, whom he had met in Spain during the Peninsular War. Thomas Kelly succeeded Curtis (1832–35). He lived and died with the reputation of a saint.

William Crolly succeeded him (1835–49). He was the first Catholic primate to reside in Armagh, and perform episcopal functions there, since the introduction of the Penal Laws. He began construction of St. Patrick's Cathedral, which took more than sixty years to bring to completion. The foundation-stone was laid 17 March 1840, and before the primate's death, the walls had been raised to a considerable height. Paul Cullen succeeded in 1849, but was translated to the See of Dublin in 1852. In 1850 he presided over the National Synod of Thurles, the first synod held in Ireland since the convention of the bishops and clergy in Kilkenny in 1642.

Joseph Dixon (1852–66), the next primate, held a synod in Drogheda in 1854, at which all the northern bishops assisted. Archbishop Dixon resumed the building of the cathedral, but did not live to see it finished. Michael Kieran (1866–69) succeeded, residing in Dundalk during his tenure of the primatial see. His successor, Daniel McGettigan (1870–87), spent three years of earnest labour in the completion of the cathedral, and was able to open it in 1873. He was succeeded by Cardinal Michael Logue, who succeeded to the primacy in 1887. He was the first Primate of Armagh to become a member of the College of Cardinals. He devoted himself for several years to the task of beautifying and completing in every sense the noble edifice. In the building of the sacristy, library, synod-hall, muniment-room, the purchase in fee-simple of the site, and the interior decorations and altars, he spent more than £50,000 on the cathedral. This great cathedral was consecrated on 24 July 1904. Cardinal Vincenzo Vannutelli, representing Pope Pius X, was present at the consecration.

Redemptoris Mater Seminary

A House of Formation was founded in 2012 by Cardinal Seán Brady and in 2016,[1] the Redemptoris Mater Seminary was officially opened (in the former De La Salle monastery), in Dundalk, County Louth, in the Archdiocese of Armagh,[2] it is a diocesan seminary that operates under the auspices of the Neocatechumenal way.[3] Seminarians travel to Maynooth College for philosophical and theological studies.[4] The first ordination took place in 2014. Rev. Giuseppe Pollio from Italy, serves as rector of the seminary.[5] In 2022, Archbishop Eamon Martin, laid the foundation stone for an extension to the seminary.[6]

Adult Faith Programmes

The Armagh Diocese in conjunction with St. Patrick's College, Maynooth commenced in 2019, Certificate, Diploma and Degree programmes in Theology (Adult Education and Pastoral Ministry) in Armagh and Dundalk.[7][8] The archdiocese of Armagh is one of the regional locations where Maynooth run the Diploma in Diaconate Studies programme.

Ordinaries

List of recent archbishops:[9][10]

- Michael Kieran (1867–1869)

- Daniel McGettigan (1870–1887)

- Cardinal Michael Logue (1887–1924)

- Cardinal Patrick O'Donnell (1924–1927)

- Cardinal Joseph MacRory (1928–1945)

- Cardinal John D'Alton (1946–1963)

- Cardinal William John Conway (1963–1977)

- Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich (1977–1990)

- Cardinal Cahal Daly (1990–1996)

- Cardinal Seán Brady (1996–2014)

- Eamon Martin (2014 – present)

See also

- Roman Catholicism in Ireland

- List of Roman Catholic dioceses in Northern Ireland

- List of Roman Catholic dioceses (alphabetical) (including archdioceses)

- List of Roman Catholic dioceses (structured view) (including archdioceses)

- List of Roman Catholic archdioceses (by country and continent)

- Apostolic Nuncio to Ireland

References

- New Armagh seminary is blessed by Cian Molloy, catholicireland.net, 26 November 2018.

- Redemptoris Mater Seminary, Dundalk Co. Louth

- Support Neocatechumenal Way in Ireland.

- Archbishop Eamon Martin officially opens new Irish missionary seminary Catholic Bishops Conference, 25 November 2016.

- Redemptoris Mater house of formation, Dundalk, Diocese of Armagh (Ireland)

- Sustained growth in vocations leads to extension of Armagh Archdiocese seminary in Dundalk by Ruth O'Connell, LMFM, February 12, 2022.

- Affiliated Programmes Kalendarium (2020-2021), St. Patrick's College, Maynooth.

- Theology Programme Armagh Diocesan Pastoral Plan.

- "Former Archbishops of Armagh". Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1986). Handbook of British Chronology (Third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 415–416. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Coleman, Ambrose (1907). "Archdiocese of Armagh". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Coleman, Ambrose (1907). "Archdiocese of Armagh". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.