Prussian Crusade

The Prussian Crusade was a series of 13th-century campaigns of Roman Catholic crusaders, primarily led by the Teutonic Knights, to Christianize under duress the pagan Old Prussians. Invited after earlier unsuccessful expeditions against the Prussians by Christian Polish kings, the Teutonic Knights began campaigning against the Prussians, Lithuanians and Samogitians in 1230. By the end of the century, having quelled several Prussian uprisings, the Knights had established control over Prussia and administered the conquered Prussians through their monastic state, eventually erasing the Prussian language, culture and pre-Christian religion by a combination of physical and ideological force. Some Prussians took refuge in neighboring Lithuania.

Early missions and conflicts

Wulfstan of Hedeby, an agent of Alfred of Wessex, recorded the seafaring and cattle-herding Prussians as a strong and independent nation.[1] Mieszko I of the Polans tried to extend his realm from land he had just conquered around the mouth of the Oder as far as Prussia.[2] Bolesław I of Poland, son of Mieszko I, greatly expanded his land conquests and used Adalbert of Prague for his aim of conquering the Prussians in 997, but the missionary was killed by the natives. After some initial success among the Prussians, Adalbert's successor, Bruno of Querfurt, was also killed in 1009.[3] Bolesław I continued his conquests of surrounding lands and in 1015 he devastated the native populations of large parts of Prussia.

The Poles waged war with the neighboring Prussians, Sudovians, and Wends over the following two centuries.[4][5][6] While the Poles sought control over the Prussians under the aegis of facilitating the conversion of the Prussians to Christianity, the Prussians engaged in reciprocal raids, capturing slaves in the bordering territories of Chełmno Land and Masovia.[7] Many Prussians nominally accepted baptism under duress only to revert to native religious beliefs after hostilities ended. Henry of Sandomierz was killed fighting the Prussians in 1166.[8] Bolesław IV and Casimir II each led large armies into Prussia; while Bolesław's forces were defeated in guerilla warfare, Casimir imposed peace until his death in 1194.[9] King Valdemar II of Denmark supported Danish expeditions against Samland until his capture by Henry I, Count of Schwerin, in 1223.

In 1206, the Cistercian bishop Christian of Oliva, with the support of the King of Denmark and Polish dukes, found colonization of the natives in a better state than expected upon his arrival in the war-torn Chełmno Land. Inspired, he travelled to Rome to prepare for a larger mission. When he returned to Chełmno in 1215, however, Christian found the Prussians hostile out of outrage at the actions of the Sword-Brothers in Livonia[10] or fear of Christian Polish expansion.[11] The Prussians invaded Chełmno Land, and Pomerellia,[12] besieged Chełmno and Lubawa, and enabled Christian converts to return to their native, pre-Christian beliefs.[13]

Because of the growing intensity of reciprocal attacks,[14] Pope Honorius III sent a papal bull to Christian in March 1217 allowing him to begin preaching a crusade against the resisting Prussians. The following year the Prussians counter-attacked Chełmno Land and Masovia again, plundering 300 cathedrals and churches in revenge.[15] Duke Conrad of Masovia succeeded in making the Prussians leave by paying a huge tribute, which only encouraged the Prussians, however.[15]

Crusade of 1222/23

Honorius III called for a crusade under the leadership of Christian of Oliva and chose as papal legate the Archbishop of Gniezno, Wincenty I Niałek.[15] German and Polish crusaders began gathering in Masovia in 1219, but serious planning only began in 1222 upon the arrival of nobles such as Duke Henry of Silesia, Archbishop Laurentius of Breslau (Wroclaw), and Laurentius of Lebus. Numerous Polish nobles began endowing Christian's Bishopric of Prussia with estates and castles in Chełmno Land during the meantime. The lords agreed that the primary focus was to rebuild the colonizing fortresses of Chełmno Land, especially Chełmno itself, whose fortress was almost completely rebuilt.[16] By 1223, however, most of the crusaders had left the region, and the Prussians devastated Chełmno Land and Masovia yet again, forcing Duke Conrad to seek refuge in the castle of Płock. The Sarmatians (as they were then known) even reached Gdańsk (Danzig) in Pomerellia.[17]

In 1225[18] or 1228,[19] fourteen north German knights were recruited by Conrad and Christian to form a military order. First granted the estate of Cedlitz in Kuyavia until the completion of a castle at Dobrzyń, the group became known as the Order of Dobrzyń (or Dobrin).[20] The Knights of Dobrzyń initially had success driving the Prussians from Chełmno Land, but a Prussian counterattack against them and Conrad killed most of the Order. The survivors were granted asylum in Pomerania by Duke Swantopelk II. The Order of Calatrava, granted a base near Gdańsk, was also ineffective.[12]

Invitation of the Teutonic Order

While in Rome, Christian of Oliva had made the acquaintance of Hermann von Salza, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order from 1209 to 1239. With the permission of Duke Conrad of Masovia and the Masovian nobility, Christian requested aid from the Teutonic Order against the Prussians in 1226. Stability with the Prussians would then allow Conrad to pursue becoming High Duke of Poland.[21] While Hermann was interested in the Polish offer, his focus was on assisting Emperor Frederick II with the Fifth Crusade. Because the Teutonic Order had recently been expelled from the Burzenland in the Kingdom of Hungary, Hermann also desired greater autonomy for his forces in future endeavors.

Hermann met with Frederick II at Rimini and suggested that the subjugation of the Prussians would make the Holy Roman Empire's borders easier to defend against invaders, presumably referring to Lithuanian counterattacks against Christian crusades.[22] The Holy Roman Emperor gave his approval of the enterprise in the Golden Bull of Rimini of 1226, granting them Chełmno Land, or Culmerland, and any future conquests. The mission to convert the Prussians remained under the command of Bishop Christian of Oliva.[23]

Before beginning the campaign against the Prussians, the Teutonic Order allegedly signed the Treaty of Kruszwica with the Poles on June 16, 1230, by which the Order was to receive Culmerland and any future conquests, similar to the terms of the Golden Bull of Rimini. The agreement has been disputed by historians; the document has been lost and many Polish historians have doubted its authenticity and the Teutonic Order's territorial claims. However, recent studies by Polish historians have established the treaty's legitimacy.[24] From the viewpoint of Duke Conrad, Chełmno was only to be used as a temporary base against the Prussians and future conquests were to be under the authority of the Duke of Masovia. However, Hermann von Salza saw the document as granting the Order autonomy in all territorial acquisitions, aside from allegiance to the Holy See and the Holy Roman Emperor.[25] The Golden Bull of Rieti issued by Pope Gregory IX in 1234 reaffirmed the Order's control of conquered lands, placing them only under the authority of the Holy See.

The 14th century chronicler Peter von Dusburg mentioned eleven districts in Prussia: Bartia, Culmerland (formerly under Polish control), Galindia, Nadrovia, Natangia, Pogesania, Pomesania, Samland, Scalovia, Sudovia, and Ermland. Peter estimated that while most tribes could muster about 2,000 cavalry, Samland could raise 4,000 cavalry and 40,000 infantry, while Sudovia had 6,000 cavalry and "an almost innumerable multitude of other warriors".[26] In contrast, the Prussians of ravaged Culmerland could raise fewer troops than the other tribes. Galindia, a forested wilderness of lakes and rivers, also had a small population to raise troops from. Modern estimates indicate a total Prussian population of 170,000, smaller than that suggested by Peter von Dusburg.[26]

Initial Teutonic campaigns

After receiving or forging the claim to Culmerland in 1230,[27] Hermann von Salza dispatched Conrad von Landsberg[28] as his envoy[29] with a small force of seven Teutonic Knights and 70–100 squires and sergeants[30] to Masovia as a vanguard. They took possession of Vogelsang (German for "bird song"), a castle being built by Conrad opposite the future Thorn (Toruń).[30] Other sources indicate that two knights constructed Vogelsang in 1229, but were killed by Prussians soon after.[31] Soon after arriving at Vogelsang, Conrad von Landsberg began ordering small raids against pagans on the south side of the Vistula,[30] a region that was relatively safe with a mixed Christian and pagan population. Reinforcements began arriving at Vogelsang after the castle's completion. Led by Hermann Balk, a force numbering twenty knights and 200 sergeants arrived in 1230.

While the earlier Polish expeditions had usually marched eastward into the Prussian wilderness, the Order focused in the west to establish fortresses along the Vistula River. They campaigned annually whenever crusading knights from the west arrived. The early campaigns were primarily composed of Polish, German, and Pomeranian crusaders, as well as some Prussian militiamen auxiliaries. The Polish and Pomerellian dukes proved essential through their providing of troops and bases. Most of the secular crusaders would return to their homes after the end of the campaigns, leaving the monastic Teutonic Knights the task of consolidating the gains and garrisoning the newly built forts, most of which were small and made of timber.[32] Some secular Polish knights were granted vacant territories, especially in Culmerland, although most of the conquered territory was retained by the Teutonic Order. Colonists from the Holy Roman Empire began to immigrate eastward, allowing the foundation of a new town each year, many of which were granted Kulm law.[33]

The crusaders began campaigning against the neighboring Pomesanians and their leader Pepin. Advancing from Nessau (Nieszawa) with the aid of Conrad of Masovia, Balk took control of ruins at modern Toruń and advanced toward the pagan-occupied Rogów. A local Prussian captain defected and handed that castle to the crusaders, who then destroyed the Prussian fort of Quercz or Gurske. The defecting captain then tricked Pipin into being captured by the Knights, ending Prussian resistance in the Culmerland.[34] By 1232, the Knights had established or rebuilt fortresses at Culm (Chełmno) and Thorn. Pope Gregory IX called for reinforcements, which included 5,000 veterans under the leadership of the Burgrave of Magdeburg.[35]

In summer 1233, the Knights led a crusading army of 10,000[36] and established a fortress at Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) in Pomesania. The Pomerellian dukes Swantopelk and Sambor supported a smaller army for an invasion of Pogesania during the winter of 1233–34. After a close battle, the pagan Pogesanians were routed on the frozen Sirgune River by the arrival of the ducal cavalry,[36] and the battlefield was subsequently known as the "Field of the Dead".[37] The building of a fortress at Rehden (Radzyń Chełmiński) stabilized the eastern Culmerland in 1234.[38]

The bishop of Prussia, Christian of Oliva, claimed two-thirds of conquered territory, granting one-third to the Teutonic Order. The papal legate William of Modena mediated between the two sides, granting the Knights two-thirds but reserving extra rights for the bishop. The Teutonic Knights also sought the incorporation of the small Order of Dobrzyń into the larger Teutonic Order. Conrad of Masovia was furious with this proposal and demanded the return of the Dobrzyń Land, which the Knights were reluctant to do; Duke Conrad subsequently refused to aid the crusaders any further.[39] With the approval of the pope and the bishop of Płock, the Teutonic Knights assimilated the Order of Dobrzyń in a bull on April 19, 1235; the displeased Conrad of Masovia had the castle of Dobrzyń returned to him.[18] In 1237 the Teutonic Knights assimilated the Sword-Brothers or Livonian Order, a military order active in Livonia, after they were nearly wiped out by Lithuanians in the Battle of Saule.

With the support of Henry III, Margrave of Meissen, in 1236, the crusaders advanced north along both banks of the Vistula and forced the submission of most Pomesanians. Although Henry did not participate in the 1237 campaign against the Pogesanians, the margrave supplied the Order with two large river-boats which defeated the smaller craft used by the Prussian tribes. Near the Prussian settlement of Truso, Elbing (Elbląg) was founded with colonists from Lübeck, while Christburg (Dzierzgoń) protected the land east of Marienwerder.

From 1238 to 1240, the Teutonic Knights campaigned against the Bartians, Natangians, and Warmians. A small force of crusading knights were slaughtered besieging the Warmian fort of Honeida,[40] leading Marshal Dietrich von Berheim to return with a larger army. When the Warmian commander Kodrune advised that the pagans should surrender and convert, Honeida's own garrison killed him, leading Dietrich to order a successful capture of the fort.[41] The fort on the Vistula Lagoon was renamed Balga and rebuilt in 1239 to protect the Order's territory in Ermeland. A Prussian counterattack to reclaim the fort failed, and the local Prussian leader Piopso was killed.[42] Seasonal reinforcements led by Otto I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg[42] consolidated Teutonic control over Natangia and Bartia.[32]

In a bull of October 1, 1243, Pope Innocent IV and William of Modena divided Prussia into the Dioceses of Culm, Pomesania, Ermeland, and Samland, although the territory of the last had not yet been conquered.

First Prussian Uprising

The Teutonic Knights' further advance into Prussia was slowed by the outbreak of the First Prussian Uprising in 1242. Alarmed by the crusaders' rapid expansion into territory bordering his lands, the Christian Duke Swantopelk of Pomerellia allied with the conquered Prussians and supported an armed rebellion against the crusaders. The Teutonic Order's capacity to resist was weakened, as there were fewer German crusaders arriving and the Polish princes were feuding amongst themselves.

The crusaders' cavalry and crossbow artillery proved overwhelming in level terrain, but the Prussians were more experienced and maneuverable in smaller skirmishes in wooded terrain. While the Prussian and Pomerellian troops captured the majority of the Order's castles and defeated the Knights at Rensen in 1244, they lacked the siege capabilities to finish the Knights off. The Germans used their politics and diplomacy to divide Swantopelk from the Prussians. The Poles sought the Pomerellian prince's territory along the Vistula, while the papal legate, the future Pope Urban IV, wanted the Christians to direct their energies against pagans instead of each other. Swantopelk ceased aiding the Prussians in 1248, while most of the latter agreed to peace in the Treaty of Christburg in February 1249. The treaty granted civil liberties and considerable autonomy to native converts to Christianity. While the majority of tribes followed the terms of the treaty, intermittent fighting continued until 1253, with the Natangians even defeating the Order at Krücken in November 1249.

Samland

After the western Prussians were forcibly colonized by the early 1250s, the Teutonic Knights continued their advance north and east, next facing the Sambians of thickly-populated Samland. Komtur Heinrich Stango of Christburg led an army across the Vistula Lagoon in 1252, with the intention of attacking Romuve. The Sambians defeated the crusaders in battle, however, killing Stango in the process.[43] To replace the fallen soldiers, the pope and Poppo von Osterna, the new Grand Master, began preaching a crusade against the Sambians. In 1253 Poppo and the Provincial Master, Dietrich von Grüningen, as well as the Margrave of Meissen, reduced the resisting Galindians but spared too much further violence; the Order was concerned that the Prussians would seek to join Poland if they were pressed too greatly.[44] With the resisting tribes decimated, Pope Innocent IV directed Dominican friars to preach the crusade, and the Order sent embassies to the Kings of Hungary, Bohemia, and the princes of the Holy Roman Empire. While the Order waited for the crusaders to arrive in Prussia, the Livonian branch "founded" Memel (Klaipėda) along the Curonian Lagoon to prevent the Samogitians from assisting the Sambians. As the chronicles attest, the "founding" was accomplished by burning an existing native city to the ground and exterminating the entire population that seems to have lived there, according to contiguous archeological finds, for several millennia.

The 60,000-strong crusading army which gathered for the campaign included Bohemians and Austrians under the command of King Ottokar II of Bohemia, Moravians under Bishop Bruno of Olmütz, Saxons under Margrave Otto III of Brandenburg, and a contingent brought by Rudolph of Habsburg.[45] The Sambians were crushed at the Battle of Rudau, and the fort's garrison surrendered quickly and underwent baptism. The crusaders then advanced against Quedenau, Waldau, Caimen, and Tapiau (Gvardeysk); the Sambians who accepted baptism were left alive, but those who resisted were exterminated en masse. Samland was conquered in January 1255 in a campaign lasting less than a month.[46] Near the native settlement of Tvangste, the Teutonic Knights founded Königsberg ("King's Mountain"), named in honor of the Bohemian king. Braunsberg (Braniewo), possibly named in honor of Bruno of Olmütz or Bruno of Querfurt, was also founded nearby, likely in place of an existing native town. The Knights built the castle Wehlau (Znamensk) at the junction of the Alle and Pregel Rivers to guard against and be able to continue the colonization of the native Sudovian, Nadrovian, and Scalovian. Thirsko, a Christian Sambian chief, and his son Maidelo were entrusted with Wehlau.[47] With the assistance of Sambian levies, the Teutonic Order advanced further into Natangia, capturing the fortresses of Capostete and Ocktolite near Wohnsdorf. The Natangian leader Godecko and his two sons were killed resisting the advance.[47]

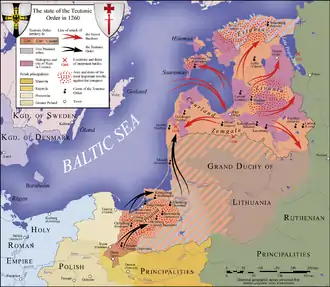

Great Prussian Uprising (1260–1274)

The Livonian Order had been invading and attempting to colonize Samogitia, which was northeast of the Prussians. The native Samogitians entered a two-year truce with the Order in 1259. In 1259 the Samogitians decided to retain the independence of their pre-Christian religion.[48] They defeated the Livonian Order at the Battle of Skuodas in 1259, and then inflicted a crushing defeat on the crusaders in the Battle of Durbe in 1260. The native victory inspired the Prussians to rebel again, starting the Great Prussian uprising the same year. In the minds of the indigenous peoples, their victories reinforced the validity of their pre-Christian beliefs.[49]

Despite their territorial gains in Prussia, the primary emphasis of the Teutonic Knights was still the Holy Land, and few reinforcements could be spared to complete the Christianization of what was then known as Sarmatia Europea. The German princes of the Holy Roman Empire were distracted by the imperial succession, and few seasonal (summer) crusaders came to the assistance of the Prussian Brothers; the first reinforcements were defeated at Pokarwis in 1261. The Order had most of its Prussian castles destroyed during the early 1260s. Besides Prussia, the natives also raided Livonia, Poland, and Volhynia.

The crusaders began to stem the resistance with the assistance of Albert I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and Henry III, Landgrave of Thuringia, in 1265. In the following year German crusading reinforcements were provided by Margraves Otto III and John I of Brandenburg, and the castle of Brandenburg (Ushakovo) was founded in their honor. King Ottokar II of Bohemia briefly returned to Prussia in 1267–68, but was deterred by poor weather, while Margrave Dietrich II of Meissen also campaigned with the Order in 1272.[50] The crusaders gradually killed or forced the surrender of each Prussian tribes' war leader while exterminating the native population en masse if it refused to convert to Christianity.

As a result of the uprising, many native Prussians lost some of the rights they had received in the Treaty of Christburg and were subsequently reduced to serfdom. Numerous Prussians fled to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania or to Sudovia, while others were forcibly resettled by the crusaders. The tribal chiefs who remained in Prussia became vassals of the Teutonic Knights, who began rebuilding their castles in stone or brick to provide greater protection against the restive colonized population.

Later campaigns

Although the Teutonic Knights' offensive capability was greatly weakened during the Great Pagan Uprising, they did engage in some campaigns against the pagan on their eastern flank. The Bartians, Natangians, and Warmians had converted to Christianity, but the Sudovians and Lithuanians to their east remained pagan and continued their border warfare with the Teutonic Knights. Led by Skalmantas during the Great Uprising, the Sudovians sacked Bartenstein (Bartoszyce) in Bartia, which was to be the focal point of their borders. Defenseless against the Sudovians, the Natangians and Bartians allied with the Teutonic Knights for protection, although little assistance could be provided initially. The Christian Natangians clans gathered in 1274 and killed 2,000 of the Sudovian raiders; Grand Master Anno von Sangershausen recruited Thuringians and Meisseners to complete the Teutonic recovery of Natangia.[51]

Anno's successor as Grand Master, Hartmann von Heldrungen, directed the Provincial Master of Prussia, Conrad von Thierberg the Elder, to attack eastward from Königsberg along the Pregel River to separate the Sudovians from the Nadrovians. Vogt Theodoric of Samland and his militia sacked two river forts and plundered a large amount of treasure and goods. Theodoric led another crusading force, including Teutonic Knights, 150 sergeants, and Prussian infantry, against another Nadrovian fort. Although the natives attempted to surrender after siege ladders were placed, most of the warriors were slaughtered by the crusaders, with only a few natives surviving to be resettled. Conrad then led the Knights past the destroyed border forts to assault the Nadrovians main redoubt of Kaminiswike, defended by 200 warriors. Most of the natives were killed after the Knights stormed the fortress, and the Nadrovian clans surrendered soon afterward to become auxiliaries of the crusaders.[52]

The Teutonic Knights then used Nadrovia and Memel as bases against Scalovia on the lower Memel River. Scalovia would then serve as a base against pagan Samogitia, which separated Teutonic Prussia from Teutonic Livonia. Because of this threat, the Lithuanians provided assistance to the pagan Scalovians, and the crusaders and pagans each engaged in border raids to distract enemy forces. Because the pagans were strongly defended in the wilderness, the Teutonic Knights focused on travelling up the Memel River toward the strong pagan fort Ragnit. Theodoric of Samland led 1,000 men in the assault. Artillery fire forced the defenders from the ramparts, allowing the crusaders to storm the walls with ladders and slaughter most of the pagans. Theodoric also captured Romige on the other bank of the Memel. The Scalovians retaliated by sacking Labiau near Königsberg. Conrad von Thierberg escalated the conflict by sending a large raid against Scalovia. Nicholas von Jeroschin documented the crusaders as killing and capturing numerous pagans. When the Scalovian warriors went in pursuit of the captured pagans, Conrad shattered the would-be rescuers in an ambush which killed the pagan leader, Steinegele. Most Scalovian nobles quickly surrendered to the Knights in the battle's aftermath.[53]

The Teutonic Knights planned to advance against Samogitia after conquering Scalovia, but the outbreak of a new rebellion engineered by Skalmantas of the Sudovians delayed the campaign. In 1276–77 the Sudovians and Lithuanians raided Culmerland and burned settlements near the castles of Rehden, Marienwerder, Zantir, and Christburg. Theodoric of Samland was able to convince the Sambians not to rebel, and the Natangians and Warmians followed suit.[54] Conrad von Thierberg the Elder led 1,500 men into Kimenau in summer 1277, and crushed a Sudovian army of 3,000 near the Winse forest.[55] Many Pogesanians fled to the Lithuanians and were resettled at Gardinas, while the ones who remained in Prussia were resettled by the crusaders, probably near Marienburg (Malbork). This new brick castle, built to replace Zantir, guarded against further rebellions with Elbing and Christburg. The central Prussian tribes surrendered to the crusaders by 1277.[50]

The crusaders and Sudovians engaged in guerilla warfare, which the Sudovians were particularly adept at. However, they lacked the sheer numbers to deal with their German, Polish, and Volhynian adversaries, and the Sudovian nobility began gradually surrendering one by one. Marshal Conrad von Thierberg the Younger raided Pokima, capturing large amounts of cattle, horses, and prisoners. They then successfully ambushed the 3,000-strong force of pursuing Sudovians, losing only six Christians in the process.[56] In 1280 the Sudovians and Lithuanian invaded Samland, but the alerted Order had fortified their castles and deprived the raiders of provisions. While the pagans were in Samland, Komtur Ulrich Bayer of Tapiau led a devastating counter-raid into Sudovia.[57] The Polish prince Leszek the Black achieved two significant victories over the pagans, securing the Polish border, and Skalmantas fled Sudovia to Lithuania.

In summer 1283, Conrad von Thierberg the Younger was named Provincial Master of Prussia and led a large army into Sudovia, finding little resistance. The Knight Ludwig von Liebenzell, who had once been a captive of the Sudovians, negotiated the surrender of 1,600 Sudovians and their leader Katingerde, who were subsequently resettled in Samland. Most of the remaining Sudovians were redistributed to Pogesania and Samland; Skalmantas was pardoned and allowed to settle at Balga. Sudovia was left unpopulated, becoming a border wilderness that protected Prussia, Masovia, and Volhynia from the Lithuanians.[58] The Prussians rebelled in short-lived uprisings in 1286 and 1295, but the crusaders firmly controlled the Prussian tribes by the end of the 13th century.

The Prussian populace retained many of their traditions and way of life, especially after the Treaty of Christburg protected the rights of converts. The Prussian uprisings led to the crusaders only applying these rights to the most powerful converts, however, and the pace of conversion slowed. After the Prussians were militarily defeated in the second half of the 13th century, they were gradually subjected to Christianization and cultural assimilation during the following centuries as part of the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights. With the fall of Acre and Outremer and the securing of Prussia, the Order then turned its focus against Christian Pomerellia, which separated Prussia from imperial Pomerania, and against pagan Lithuania.

See also

Footnotes

- Christiansen, p. 38

- Gieysztor, p. 50

- Wyatt, pp. 22–23

- Wyatt, p. 24

- Gieysztor, p. 77

- Recent Issues in Polish Historiography of the Crusades Archived 2007-11-28 at the Wayback Machine Darius von Güttner Sporzyński. 2005

- Urban, p. 50

- Gieysztor, p. 69

- Wyatt, p. 29

- Wyatt, p. 47

- Urban, p. 51

- Gieysztor, p. 94

- Wyatt, p. 32

- Gieysztor, p. 93

- Wyatt, p. 33

- Wyatt, p. 34

- Wyatt, p. 39

- McClintock, p. 720

- Perlbach, p. 61

- Wyatt, p. 36

- Christiansen, p. 82

- Wyatt, p. 81

- Christiansen, p. 83

- Dariusz Sikorski, 'Neue Erkenntnisse ueber das Kruschwitzer Privileg' in Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung, 51 (2002), p. 317-350

- Halecki, p. 35

- Urban, p. 43

- Due to a clerical mistake by Peter von Dusburg, the arrival of the Teutonic Knights has sometimes been given as 1226; see Töppen, pp. 276–79. Töppen states von Landsberg arrived in Masovia in 1230, while Fahne states von Landsberg arrived ca. 1228; see Fahne, p. 50

- Fahne, p. 50

- Töppen, p. 276

- Urban, p. 52

- Seward, p. 101

- Christiansen, p. 106

- Urban, p. 57

- Wyatt, pp. 92–93

- Wyatt, p. 95

- Urban, p. 56

- Wyatt, p. 99

- Christiansen, p. 105

- Wyatt, p. 101

- Wyatt, p. 143

- Wyatt, p. 151

- Wyatt, p. 152

- Wyatt, pp. 203–204

- Wyatt, pp. 209–210

- Wyatt, pp. 212–213

- Wyatt, pp. 214–216

- Wyatt, pp. 216–217

- Urban, p. 59

- Urban p.59

- Christiansen, p. 108

- Urban, p. 63

- Urban, pp. 64–65

- Urban, p. 67

- Urban, p. 70

- Wyatt, p. 259

- Urban, p. 71

- Wyatt, p. 262

- Urban, p. 78

References

- Christiansen, Erik (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books. p. 287. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- Fahne, Anton (1875). Livland: Ein Beitrag zur Kirchen- und Sitten-Geschichte (in German). Düsseldorf: Schaub'sche Buchhandlung. p. 240.

- Gieysztor, Aleksander; Stefan Kieniewicz; Emanuel Rostworowski; Janusz Tazbir; Henryk Wereszycki (1979). History of Poland. Warsaw: PWN. p. 668. ISBN 83-01-00392-8.

- Halecki, Oskar (1970). A History of Poland. New York: Roy Publishers. p. 366. ISBN 0-679-51087-7.

- McClintock, John; James Strong (1883). Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature: Vol. VIII: PET-RE. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 1086.

- Perlbach, Max (1886). Preussisch-Polnische Studien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters (in German). Halle: Max Niemeyer. p. 128.

- Seward, Desmond (1995). The Monks of War: The Military Religious Orders. London: Penguin Books. p. 416. ISBN 0-14-019501-7.

- Töppen, Max (1853). Geschichte der Preussischen Historiographie von P. v. Dusburg bis aus auf K. Schütz (in German). Berlin: Verlag von Wilhelm Hertz. p. 290.

- Urban, William (2003). The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. London: Greenhill Books. p. 290. ISBN 1-85367-535-0.

- Wyatt, Walter James (1876). The History of Prussia, Volume 1. London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 506.