Blue-footed booby

The blue-footed booby (Sula nebouxii) is a marine bird native to subtropical and tropical regions of the eastern Pacific Ocean. It is one of six species of the genus Sula – known as boobies. It is easily recognizable by its distinctive bright blue feet, which is a sexually selected trait and a product of their diet. Males display their feet in an elaborate mating ritual by lifting them up and down while strutting before the female. The female is slightly larger than the male and can measure up to 90 cm (35 in) long with a wingspan up to 1.5 m (5 ft).[2]

| Blue-footed booby Temporal range: Holocene–recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| A blue-footed booby at the Galápagos Islands | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Suliformes |

| Family: | Sulidae |

| Genus: | Sula |

| Species: | S. nebouxii |

| Binomial name | |

| Sula nebouxii Milne-Edwards, 1882 | |

_world2.png.webp) | |

| Range shown by red area | |

The natural breeding habitats of the blue-footed booby are the tropical and subtropical islands of the Pacific Ocean. It can be found from the Gulf of California south along the western coasts of Central and South America to Peru. About half of all breeding pairs nest on the Galápagos Islands.[3] Its diet mainly consists of fish, which it obtains by diving and sometimes swimming under water in search of its prey. It sometimes hunts alone, but usually hunts in groups.[4]

%252C_Las_Bachas%252C_isla_Santa_Cruz%252C_islas_Gal%C3%A1pagos%252C_Ecuador%252C_2015-07-23%252C_DD_17.jpg.webp)

The blue-footed booby usually lays one to three eggs at a time. The species practices asynchronous hatching, in contrast to many other species whereby incubation begins when the last egg is laid and all chicks hatch together. This results in a growth inequality and size disparity between siblings, leading to facultative siblicide in times of food scarcity.[5] This makes the blue-footed booby an important model for studying parent–offspring conflict and sibling rivalry.

Taxonomy

The blue-footed booby was described by the French naturalist Alphonse Milne-Edwards in 1882 under the current binomial name Sula nebouxii.[6] The specific epithet was chosen to honor the surgeon, naturalist, and explorer Adolphe-Simon Neboux (1806–1844).[7] There are two recognized subspecies:[8]

- S. n. nebouxii Milne-Edwards, 1882 – Pacific coast of Southern and Middle America

- S. n. excisa Todd, 1948 – Galápagos Islands[9]

Its closest relative is the Peruvian booby. The two species likely split from each other recently due to their shared ecological and biological characteristics.[10] A 2011 study of multiple genes calculated the two species diverged between 1.1 and 0.8 million years ago.[11]

The name booby comes from the Spanish word bobo ("stupid", "foolish", or "clown") because the blue-footed booby is, like other seabirds, clumsy on land.[3] They are also regarded as foolish for their apparent fearlessness of humans.[2]

Description

_on_Santa_Cruz%252C_Gal%C3%A1pagos_Islands.JPG.webp)

The blue-footed booby is on average 81 cm (32 in) long and weighs 1.5 kg (3+1⁄4 lb), with the female being slightly larger than the male. Its wings are long, pointed, and brown in color. The neck and head of the blue-footed booby are light brown with white streaks, while the belly and underside exhibit pure white plumage.[12] Its eyes are placed on either side of its bill and oriented towards the front, enabling excellent binocular vision. Its eyes are a distinctive yellow, with the male having more yellow in its irises than the female. Blue-footed booby chicks have black beaks and feet and are clad in a layer of soft white down. The subspecies S. n. excisa that breeds on the Galápagos Islands is larger than the nominate subspecies and has lighter plumage especially around the neck and head.[9]

The Peruvian booby is similar in appearance, but has grey feet, whiter head and neck, and white spots on its wing coverts. The ranges of the two species overlap in the waters of northern Peru and southern Ecuador.[13]

Since the blue-footed booby preys on fish by diving headlong into the water, its nostrils are permanently closed, and it has to breathe through the corners of its mouth. Its most notable characteristic is its blue-colored feet, which can range in color from a pale turquoise to a deep aquamarine. Males and younger birds have lighter feet than females.[2] Its blue feet play a key role in courtship rituals and breeding, with the male visually displaying his feet to attract mates during the breeding season.

Distribution and habitat

The blue-footed booby is distributed among the continental coasts of the eastern Pacific Ocean from California to the Galápagos Islands south into Peru.[14] It is strictly a marine bird. Its only need for land is to breed and rear young, which it does along the rocky coasts of the eastern Pacific.[13]

A booby may use and defend two or three nesting sites, which consist of bare black lava in small divots in the ground, until they develop a preference for one a few weeks before the eggs are laid. These nests are created as parts of large colonies. While nesting, the female turns to face the sun throughout the day, so the nest is surrounded by excrement.

Natal dispersal

Females start breeding when they are 1 to 6 years old, while males start breeding when they are 2 to 6 years old. Very limited natal dispersal occurs, meaning that young pairs do not move far from their original natal nests for their own first reproduction, leading to the congregation of hundreds of boobies in dense colonies. The benefit of limited dispersal is that by staying close to their parents' nesting sites, the boobies are more likely to have a high-quality nest. Since their parents had successfully raised chicks to reproductive age, their nest site must have been effective, either by providing cover from predation and parasitism, or by its suitability for taking off and landing.[15] Bigamy has been observed in the species, and cases are known where two females and one male all share a single nest.[16]

Foot pigmentation

The blue color of the blue-footed booby's webbed feet comes from structures of aligned collagens in the skin modified by carotenoid pigments obtained from its diet of fresh fish. The collagens are arranged in a manner that makes the skin appear blue. The underlying color is a "flat, purplish blue". That color is modified by carotenoids to aquamarine in healthy birds. Carotenoids also act as antioxidants and stimulants for the blue-footed booby's immune function, suggesting that carotenoid pigmentation is an indicator of an individual's immunological state.[17][18] Blue feet also indicate the current health condition of a booby. Boobies that were experimentally food-deprived for 48 hours experienced a decrease in foot brightness due to a reduction in the amount of lipids and lipoproteins that are used to absorb and transport carotenoids. Thus, the feet are rapid and honest indicators of a booby's current level of nourishment.[17] As blue feet are signals that reliably indicate the immunological and health condition of a booby, coloration is favored through sexual selection.

Female selection

The brightness of the feet decreases with age, so females tend to mate with younger males with brighter feet, which have higher fertility and greater ability to provide paternal care than older males. In a cross-fostering experiment, foot color reflects paternal contribution to raising chicks; chicks raised by foster fathers with brighter feet grew faster than chicks raised by foster males with duller feet.[19] Females continuously evaluate their partners' condition based on foot color. In one experiment, males whose partners had laid a first egg in the nest had their feet dulled by make-up. The female partners laid smaller second eggs a few days later. As duller feet usually indicate a decrease in health and possibly genetic quality, it is adaptive for these females to decrease their investment in the second egg. The smaller second eggs contained less yolk concentration, which could influence embryo development, hatching success, and subsequent chick growth and survival. In addition, they contained less yolk androgens.[20] As androgen plays an important role in chick survival, the experiment suggested female blue-footed boobies use the attractiveness and perceived genetic quality of their mates to determine how much resources they should allocate to their eggs.[17] This supports the differential allocation theory, which predicts that parents invest more in the care of their offspring when paired with attractive mates.[17]

Male selection

Males also assess their partner's reproductive value and adjust their own investment in the brood according to their partner's condition. Females that lay larger and brighter eggs are in better condition and have greater reproductive value. Therefore, males tend to display higher attentiveness and parental care to larger eggs, since those eggs were produced by a female with apparent good genetic quality. Smaller, duller eggs garnered less paternal care. Female foot color is also observed as an indication of perceived female condition. In one experiment, the color of eggs was muted by researchers, males were willing to exercise similar care for both large eggs and small eggs if his mate had brightly colored feet, whereas males paired with dull-footed females only incubated larger eggs. Researchers also found that males did not increase their care when females exhibited both bright feet and high-quality offspring.[21]

Behavior and ecology

Hunting and feeding

%252C_feeding_of_the_juvenile_at_Seymour_Norte_(9263).jpg.webp)

The blue-footed booby is a specialized fish eater, feeding on small schooling fish such as sardines, anchovies, mackerel, and flying fish. It will also take squid and offal. The blue-footed booby hunts by diving into the ocean after prey, sometimes from a great height, and can also swim underwater in pursuit of its prey. It can hunt singly, in pairs, or in larger flocks. Boobies travel in parties of about 12 to areas of water with large schools of small fish. When the lead bird sees a fish shoal in the water, it signals to the rest of the group and they all dive in unison, pointing their bodies down like arrows.[4]

Plunge diving can be done from heights of 10–30.5 m (33–100 ft) and even up to 100 m (330 ft). These birds hit the water around 97 km/h (27 m/s) and can go to depths of 25 m (80 ft) below the water surface. Their skulls contain special air sacs that protect the brain from enormous pressure.[2] Prey are usually eaten while the birds are still under water. Individuals prefer to eat on their own instead of with their hunting group, usually in the early morning or late afternoon.[22] Males and females fish differently, which may contribute to why blue-foots, unlike other boobies, raise more than one young. The male is smaller and has a proportionally larger tail, which enables the male to fish in shallow areas and deep waters. The female is larger and can carry more food. Both the male and female feed the chicks through regurgitation.[22]

Breeding

The blue-footed booby is monogamous, although it has the potential to be bigamous.[16] It is an opportunistic breeder, with the breeding cycle occurring every 8 to 9 months.[23] The courtship of the blue-footed booby consists of the male flaunting his blue feet and dancing to impress the female. The male begins by showing his feet, strutting in front of the female. Then, he presents nest materials and finishes the mating ritual with a final display of his feet.[24] The dance also includes "sky-pointing", which involves the male pointing his head and bill up to the sky while keeping the wings and tail raised.[25]

_-displaying.jpg.webp) Displaying (sky-pointing)

Displaying (sky-pointing)_-one_leg_raised.jpg.webp) Another way of displaying by raising a foot

Another way of displaying by raising a foot

Rearing young

The blue-footed booby is one of only two species of booby that raises more than one chick in a breeding cycle.

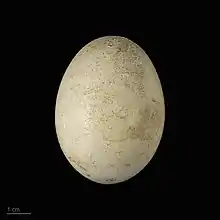

The female blue-footed booby lays two or three eggs, about four to five days apart. Both male and female take turns incubating the eggs, while the nonsitting bird keeps watch. Since the blue-footed booby does not have a brooding patch, it uses its feet to keep the eggs warm. The incubation period is 41–45 days. Usually, one or two chicks are hatched from the two or three eggs originally laid. The male and female share parental responsibilities. The male provides food for the young in the first part of their lives because of his specialized diving. The female takes over when the demand is higher.[10] Chicks feed off the regurgitated fish in the adult's mouth. If the parent blue-footed booby does not have enough food for all of the chicks, it will only feed the biggest chick, ensuring that at least one will survive.[5]

Like other sexually size-dimorphic birds, female blue-footed boobies usually favor the smaller sex during times of food scarcity. Booby chicks do not show clear differences in size based on sex, but females do grow faster than males, which means they require greater parental investment. Blue-footed boobies display behavior that is described in the flexible investment hypothesis, which states that a female adjusts the allocation of resources to maximize her lifetime reproductive success. This was shown in an experiment in which females had their flight feathers trimmed, so that they had to expend more energy during flights to obtain food for their broods. Female chicks of such mothers were more strongly affected than their brothers, in that they had lower masses and shorter wing lengths.[26]

Fledglings are more likely to become reproductive adults when one parent is old and the other young. The reason for this is unknown, but nestlings with different aged parents are least infected by ticks.[27]

With egg and new young

With egg and new young Chick

Chick

Brood hierarchy due to asynchronous hatching

The blue-footed booby lays one to three eggs in one nest at a time, although 80% of nests only contain two eggs.[28] Eggs are laid five days apart. After the first egg is laid, it is immediately incubated, which results in a difference in chick hatching times. The first chick hatches four days before the other, so it receives a four-day head start in growth compared to its younger sibling. This asynchronous hatching serves many purposes. First, it spaces out the difficult time period in rearing during which newborn chicks are too feeble to accept regurgitated food. In addition, it reduces the chance that parents will suffer total brood loss to predators such as the milk snake.[29]

Asynchronous hatching may also reduce sibling rivalry. Experimentally manipulated synchronous broods produced more aggressive chicks; chicks in asynchronous broods were less violent. This pattern of behavior arguably occurs through a clearly established brood hierarchy in asynchronously hatched siblings. Although asynchronous hatching is not vital for the formation of brood hierarchies (the experimentally synchronous broods established them, as well), it does aid in efficient brood reduction when food levels are low. Subordinate chicks in asynchronous broods die more quickly, thus relieving the parents of the burden of feeding both offspring when resources are insufficient to properly do so.[30]

Facultative siblicide

Blue-footed booby chicks practice facultative siblicide, opting to cause the death of a sibling based on environmental conditions. The A-chick, which hatches first, will kill the younger B-chick if a food shortage exists. The initial size disparity between the A-chick and B-chick is retained for at least the first two months of life.[29] During lean times, the A-chick may attack the B-chick by pecking at its younger sibling vigorously, or it may simply drag its younger sibling by the neck and oust it from the nest. Experiments in which the necks of chicks were taped to inhibit food ingestion showed that sibling aggression increased sharply when the weight of the A-chicks dropped below 20-25% of their potential. A steep increase in pecking occurred below that threshold, indicating that siblicide is, in part, triggered by the dominant chick's weight, and not simply by the size difference between the siblings. Younger broods (those less than six weeks old) had three times the rate of pecking than older broods. This is perhaps due to the relative inability of young B-chicks to defend themselves against an A-chick attack.[31]

The elder sibling also may harm the younger one by controlling access to the food delivered by the parents. A-chicks always receive food before B-chicks. Although subordinate chicks beg just as much as their dominant siblings, the older chicks are able to divert the parents' attention to themselves, as their large size and conspicuousness serve as more effective stimuli.[29]

However, another experiment showed that booby chicks do not operate exclusively by the "leftovers hypothesis", where younger chicks are fed only after the elder ones are completely satiated. Instead, researchers identified a certain degree of tolerance towards the younger sibling during short-term periods of food shortages. This hypothesis suggests that the elder chicks reduce food intake moderately, just enough so that the younger sibling does not starve. Although this system works during short-term food shortages, it is unsustainable during prolonged periods of dearth. In this latter case, the elder sibling usually becomes aggressive and siblicidal.[32]

Parental role in siblicide

Blue-footed booby parents are passive spectators of this intrabrood conflict. They do not intervene in their offspring's struggles, even at the point of siblicide. Booby parents even appear to facilitate the demise of the younger sibling by creating and maintaining the inequality between the two chicks. They reinforce the brood hierarchy by feeding the dominant chick more often than the subordinate one. Thus, they respond to the brood hierarchy and not to the level of begging when deciding which chick to feed, as both chicks beg in equal amounts. This level of passivity towards the very possible death of their younger offspring may be an indication that brood reduction is advantageous for the parents.[31] The "insurance egg hypothesis" views the second egg and resulting chick as insurance for the parent in case the first egg does not hatch, or if food levels are higher than expected.[28]

However, booby parents may not be as indifferent as they seem. The parental behavior described above may be masking parent-offspring conflict. Blue-footed booby parents make steep-sided nests that serve to deter the early ejection of the younger chick by the older sibling. This is in direct contrast to the masked booby, a species in which siblicide is obligate due to the ease in which older siblings can eject younger chicks from their flat nests. When blue-footed booby nests were experimentally flattened, parents restored them to their original steepness.[33] Blue-footed booby chicks that were placed in masked booby nests were more likely to engage in siblicide, which reveals that parental care somehow affects the level of siblicide.[34] Parents also appear to respond more frequently to chicks that are in poorer body conditions during periods of food deprivation.[35] Egg-mass analysis shows that in clutches produced at the beginning of the breeding season, the second egg in a nest were, on average, 1.5% heavier than the first. Since heavier eggs give rise to heavier chicks that have greater fitness, this evidence indicates that parents may try to rectify any disadvantages that accompany a late hatching date by investing more into the second egg.[36] Hormonal analysis of eggs also shows that no parental favoritism seems to exist in regards to androgen allocation. This may simply be because the species has evolved simpler ways to manipulate asymmetries and maximize parental reproductive output.[37] What may at first appear to be parental cooperation with the elder chick may in fact mask a genetic parent-offspring conflict.[38]

Long-term effects of hierarchies

A dominant-subordinate relationship always exists between chicks in a brood. Although dominant A-chicks grow faster and survive past infancy more often than subordinate B-chicks, no difference in reproductive success is seen between the two types of siblings during adulthood. In one longitudinal study, no long-term effects of dominance hierarchies were apparent; in fact, subordinate chicks were often observed producing nests of their own before their dominant siblings.[38]

Communication

Blue-footed boobies make raucous or polysyllabic grunts or shouts and thin whistling noises. The males of the species have been known to throw up their heads and whistle at a passing, flying female. These ritual displays are also a form of communication.

Mates can recognize each other by their calls. Although calls differed between sexes, unique individual signatures were present. Both males and females can discriminate the calls of their mates from others.[39]

Population decline

Concerns of a decline in the booby population of the Galápagos Islands prompted a research project in its cause. The project, completed in April 2014, confirmed the population decline.[40] The blue-footed booby population appears to be having trouble breeding, thus is slowly declining. The decline is feared to be long-term, but annual data collection is needed for a firm conclusion that this is not a normal fluctuation.

Food problems may be the cause of an observed failure of the birds to even try to breed. This is related to a decline in sardines (Sardinops sagax), an important part of the boobies’ diet. Earlier work on Española Island had successful breeding in blue-footed boobies that have access to sardines, in which case their diet consists essentially wholly of sardines. However, sardines have been largely absent from the Española area since 1997, as has been shown from Nazca boobies there, which also prefer sardines, but can breed using other prey. In 2012–13, roughly only half of prey items in the boobies' diet were sardines. No evidence was seen of other possible causes for the decline, such as effects of humans, introduced predators, or disease.[41]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Sula nebouxii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22696683A132588719. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22696683A132588719.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Blue-footed Booby Day". Galapagos Conservation Trust. 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- "Blue-Footed Booby". National Geographic. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Handbook of the Birds of the World Vol 1. Lynx Edicions. 1992.

- Drummond, Hugh; Gonzalez, Edda; Osorno, Jose Luis (1986). "Parent-Offspring Cooperation in the Blue-footed Booby (Sula nebouxii): Social Roles in Infanticidal Brood Reduction". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 19 (5): 365–372. doi:10.1007/bf00295710. S2CID 36417383.

- Milne-Edwards, Alphonse (1882). "Recherches sur la faune des régions Australes: Chapitre VII - Totipalmes". Annales des sciences naturelles, Zoologie. 6 (in French). 13 (4). p. 37, plate 14.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2016). "Hamerkop, Shoebill, pelicans, boobies & cormorants". World Bird List Version 6.3. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Todd, W. E. Clyde (1948). "A new booby and a new Ibis from South America". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 61: 49.

- Handbook of the Birds of the World Vol. 1. Lynx Edicions. 1992. p. 312.

- Patterson, S.A.; Morris-Pocock, J.A.; Friesen, V.L (2011). "A multilocus phylogeny of the Sulidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (2): 181–91. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.021. PMID 21144905.

- "Blue-footed Booby - Sula nebouxii". NatureWorks. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Díaz, Hernández; José Alfredo; Erika Nathalia Salazar Gómez. "Blue-footed Booby (Sula nebouxii)". Neotropical Birds Online. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- Zavalaga, Carlos B.; Benvenuti, Silvano; Dall'Antonia, Luigi; Emslie, Steven D. (2007). "Diving behavior of Blue-footed Boobies Sula nebouxii in northern Peru in relation to sex, body size and prey type". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 336: 291–303. doi:10.3354/meps336291.

- Osorio-Beristain, Marcela; Drummond, Hugh (1993). "Natal dispersal and deferred breeding in the Blue-Footed Booby" (PDF). The Auk. 110 (2).

- Castillo-Guerrero, Jose Alfredo; Mellink, Eric; Aguilar, Aaron (2005). "Bigamy in the Blue-footed Booby and the Brown Booby?". Waterbirds. 28 (3): 399–401. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2005)028[0399:bitbba]2.0.co;2.

- Velando, Alberto; Beamonte-Barrientos, Rene; Torres, Roxana (2006). "Pigment-based skin colour in the Blue-footed Booby: an honest signal of current condition used by females to adjust reproductive investment". Oecologia. 149 (3): 535–542. doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0457-5. PMID 16821015. S2CID 18852190.

- Angier, Natalie (March 6, 2017). "On Galapagos, Revealing the Blue-Footed Booby's True Colors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- Torres, Roxana; Velando, Alberto (2007). "Male reproductive senescence: the price of immune-induced oxidative damage on sexual attractiveness in the blue-footed booby". Journal of Animal Ecology. 76 (6): 1161–1168. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01282.x. PMID 17922712.

- Detressangle, Fabrice; Boeck, Lordes; Torres, Roxana (2008). "Maternal investment in eggs is affected by male feet colour and breeding conditions in the Blue-Footed Booby, Sula nebouxii". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 62 (12): 1899–1908. doi:10.1007/s00265-008-0620-6. S2CID 23627338.

- Morales, Judith; Torres, Roxana; Velando, Alberto (2012). "Safe betting: males help dull females only when they raise high-quality offspring". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 66 (1): 135–143. doi:10.1007/s00265-011-1261-8. S2CID 14882787.

- Harris, M. 2001. "Sula nebouxii" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed September 22, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Sula_nebouxii/

- Anderson, David J. (1989). "Differential responses of boobies and other seabirds in the Galápagos to the 1986–87 El Nino- Southern Oscillation event". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 52: 209–216. doi:10.3354/meps052209.

- "Blue-footed Booby, Sula nebouxii". MarineBio. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- "Blue-footed Booby". Oiseaux-birds. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- Velando, Alberto (2002). "Experimental manipulation of maternal effort produces differential effects in sons and daughters: implications for adaptive sex ratios in the Blue-footed Booby". Behavioral Ecology. 13 (4): 443–449. doi:10.1093/beheco/13.4.443.

- Ramos, A.G.; Drummond, H. (2018). "Ectoparasite burden of Blue‐footed Booby chicks depends on combined parental ages". Ibis. 160 (4): 914–918. doi:10.1111/ibi.12624.

- Velando, Alberto; Carlos Alonso-Alvarez (2003). "Differential body condition regulation by males and females in response to experimental manipulations of brood size and parental effort in the blue-footed booby". Journal of Animal Ecology. 72 (5): 846–856. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00756.x.

- Drummond, Hugh; Gonzalez, Edda; Osorno, Jose Luis (1986). "Parent-offspring cooperation in the Blue-footed Booby (Sula nebouxii): social roles in infanticidal brood reduction". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 19 (5): 365–372. doi:10.1007/bf00295710. S2CID 36417383.

- Osorno, Jose Luis; Drummond, Hugh (1995). "The function of hatching asynchrony in the Blue-footed Booby". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 37 (4): 265–273. doi:10.1007/bf00177406. S2CID 23498574.

- Drummond, Hugh; Chavelas, Cecilia Garcia (1989). "Food shortage influences sibling aggression in the Blue-footed Booby". Animal Behaviour. 37: 806–819. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(89)90065-1. S2CID 53165189.

- Anderson, David J.; Ricklefs, R. E. (1995). "Evidence of kin-selected tolerance by nestlings in a siblicidal bird". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 37 (3): 163–168. doi:10.1007/bf00176713. S2CID 19382068.

- Anderson, David J. (1995). "The Role of parents in siblicidal brood reduction of two Booby Species". The Auk. 112 (4): 860–869. doi:10.2307/4089018. JSTOR 4089018.

- Loughweed, Lynn W. (1999). "Parent Blue-footed Boobies suppress siblicidal behavior of offspring". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 45 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1007/s002650050535. S2CID 21985621.

- Villasenor, Emma; Drummond, Hugh (2007). "Honest begging in the Blue-footed Booby: signaling food deprivation and body condition". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 61 (7): 1133–1142. doi:10.1007/s00265-006-0346-2. S2CID 301883.

- D'Alba, Liliana; Torres, Roxana; Bortolotti, G.R. (2007). "Seasonal egg-mass variation and laying sequence in a bird with facultative brood reductions". The Auk. 124 (2): 643–652. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[643:sevals]2.0.co;2.

- Drummond, Hugh; Rodriguez, Cristina; Schwabl, Hubert (2008). "Do mothers regulate facultative and obligate siblicide by differentially provisioning eggs with hormones?". Journal of Avian Biology. 39 (2): 139–143. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04365.x.

- Drummond, Hugh; Torres, Roxana; Krishnana, V.V. (2003). "Buffered development: resilience after aggressive subordination in infancy". The American Naturalist. 161 (5): 794–807. doi:10.1086/375170. PMID 12858285. S2CID 24047097.

- Dentressangle, F.; Aubin, T.; Mathevon, N. (2012). "Males use time whereas females prefer harmony: individual call recognition in the dimorphic Blue-footed Booby". Animal Behaviour. 84 (2): 413–420. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.05.012. S2CID 53159414.

- Anchundia, D.; Huyvaert, K.P. & Anderson, D.J. (2014). "Chronic lack of breeding by Galápagos Blue-footed Boobies and associated population decline". Avian Conservation and Ecology. 9 (1): 6. doi:10.5751/ACE-00650-090106.

- "Blue-footed Booby Population Analysis". Galapagos Conservancy. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

External links

Data related to Sula nebouxii at Wikispecies

Data related to Sula nebouxii at Wikispecies Media related to Sula nebouxii at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sula nebouxii at Wikimedia Commons