Pubic symphysis

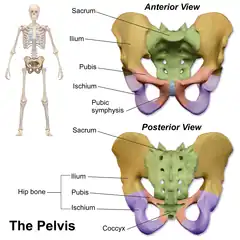

The pubic symphysis (PL: symphyses) is a secondary cartilaginous joint between the left and right superior rami of the pubis of the hip bones. It is in front of and below the urinary bladder. In males, the suspensory ligament of the penis attaches to the pubic symphysis. In females, the pubic symphysis is close to the clitoris. In most adults it can be moved roughly 2 mm and with 1 degree rotation. This increases for women at the time of childbirth.[1]

| Pubic symphysis | |

|---|---|

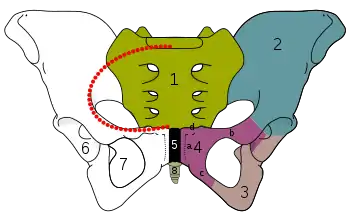

The pubic symphysis sits between and joins of the left and right superior rami of the pubic bones. | |

#5 is pubic symphysis. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | symphysis pubica, symphysis pubis |

| MeSH | D011631 |

| TA98 | A03.6.02.001 |

| TA2 | 1855 |

| FMA | 16950 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The name comes from the Greek word symphysis, meaning 'growing together'.

Structure

The pubic symphysis is a nonsynovial amphiarthrodial joint. The width of the pubic symphysis at the front is 3–5 mm greater than its width at the back. This joint is connected by fibrocartilage and may contain a fluid-filled cavity; the center is avascular, possibly due to the nature of the compressive forces passing through this joint, which may lead to harmful vascular disease.[2] The ends of both pubic bones are covered by a thin layer of hyaline cartilage attached to the fibrocartilage. The fibrocartilaginous disk is reinforced by a series of ligaments. These ligaments cling to the fibrocartilaginous disk to the point that fibers intermix with it.

Two such ligaments are the superior pubic ligament and the inferior pubic ligament, which provide the most stability; the anterior and posterior ligaments are weaker. The strong and thicker superior ligament is reinforced by the tendons of the rectus abdominis muscle, the abdominal external oblique muscle, the gracilis muscle, and by muscles of the hip. The superior pubic ligament connects together the two pubic bones superiorly, extending laterally as far as the pubic tubercles. The inferior ligament in the pubic arch is also known as the arcuate pubic ligament or subpubic ligament; it is a thick, triangular arch of ligamentous fibers, connecting together the two pubic bones below, and forming the upper boundary of the pubic arch. Above, it is blended with the interpubic fibrocartilaginous lamina; laterally, it is attached to the inferior rami of the pubic bones; below, it is free, and is separated from the fascia of the urogenital diaphragm by an opening through which the deep dorsal vein of the penis passes into the pelvis.

Fibrocartilage

Fibrocartilage is composed of small, chained bundles of thick, clearly defined, type I collagen fibers. This fibrous connective tissue bundles have cartilage cells between them; these cells to a certain extent resemble tendon cells. The collagenous fibers are usually placed in an orderly arrangement parallel to tension on the tissue. It has a low content of glycosaminoglycans (2% of dry weight). Glycosaminoglycans are long, unbranched polysaccharides (relatively complex carbohydrates) consisting of repeating disaccharide units. Fibrocartilage does not have a surrounding perichondrium. Perichondrium surrounds the cartilage of developing bone; it has a layer of dense, irregular connective tissue and functions in the growth and repair of cartilage.

Hyaline cartilage

Hyaline cartilage is the white, shiny gristle at the end of long bones. This cartilage has poor healing potential, and efforts to induce it to repair itself frequently end up with a similar, but poorer fibrocartilage.

Development

In the newborn, the symphysis pubis is 9–10 mm in width, with thick cartilaginous end-plates. By mid-adolescence the adult size is achieved. During adulthood the end-plates decrease in width to a thinner layer. Degeneration of the symphysis pubis accompanies aging and postpartum. Women have a greater thickness of this pubic disc which allows more mobility of the pelvic bones, hence providing a greater diameter of pelvic cavity during childbirth.

Function

Analysis of the pelvis shows the skinny regions function as arches, transferring the weight of the upright trunk from the sacrum to the hips. The symphysis pubis connects these two weight-bearing arches, and the ligaments that surround this pelvic region maintain the mechanical integrity.

The main motions of the symphysis pubis are superior/inferior glide and separation/compression. The functions of the joint are to absorb shock during walking and allow delivery of a baby.

Clinical significance

Injury

The pubic symphysis widens slightly when the legs are stretched far apart. In sports where these movements are often performed, the risk of a pubic symphysis blockage is high, in which case, after completion of the movement, the bones at the symphysis do not realign correctly and can get jammed in a dislocated position. The resulting pain can be severe, especially when further strain is put upon the affected joint. In most cases, the joint can only be successfully reduced into its normal position by a trained medical professional.

Disease

Metabolic diseases, such as renal osteodystrophy, produce widening, while ochronosis results in calcific deposits in the symphysis. Inflammatory diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis, result in bony fusion of the symphysis. Osteitis pubis, the most common inflammatory disease in this area, is treated with anti-inflammatory medication and rest. Degenerative joint disease of the symphysis, which can cause groin pain, results from instability or from abnormal pelvic mechanics.[3]

Symphysiolysis is separation or slipping of the symphysis. It has been estimated to occur in 0.2% of pregnancies.[4]

Pregnancy

During pregnancy in the human, hormones such as relaxin remodel this ligamentous capsule allowing the pelvic bones to be more flexible for delivery. The gap of the symphysis pubis, normally is 4–5 mm but during pregnancy there will be an increase of at least 2–3 mm, therefore, it is considered that a total width of up to 9 mm between the two bones is normal for a pregnant woman. The symphysis pubis separates to some degree during childbirth. In some women this separation can become a diastasis of the symphysis pubis. The diastasis could be the result of a rapid birth,[5] or a forceps delivery,[6] or may be a prenatal condition.[7] A diastasis of the symphysis pubis is a cause of pelvic girdle pain (PGP). Overall, about 45% of all pregnant women and 25% of all women postpartum suffer from PGP.[8]

Symphysiotomy

Symphysiotomy is a surgical procedure in which the cartilage of the pubic symphysis is divided to widen the pelvis allowing childbirth when there is a mechanical problem. It allows the safe delivery of the fetus where Caesarean section is not an option. Symphysiotomy is suggested for woman in isolated areas experiencing obstructed labor where other medical intervention is unavailable.[9]

This practice was carried out in Europe before the introduction of the Caesarean section. Historically, during obstructed labor, the skull of the fetus was also, at least occasionally, crushed in order to further facilitate the delivery.[10]

Society and culture

Use in forensic anthropology

Pubic symphyses have importance in the field of forensic anthropology, as they can be used to estimate the age of adult skeletons. Throughout life, the surfaces are worn at a fairly predictable rate. By examining the wear of the pubic symphysis, it is possible to estimate the age of the person at death.[11]

Additional images

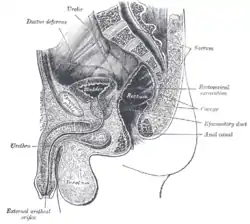

Median sagittal section of male pelvis

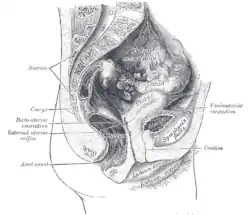

Median sagittal section of male pelvis Median sagittal section of female pelvis

Median sagittal section of female pelvis Anterior view of the body pelvis from a dissection. Pubic symphysis anteriorly.

Anterior view of the body pelvis from a dissection. Pubic symphysis anteriorly.

See also

References

- Becker, I.; Woodley, S.J.; Stringer, M.D. (2010). "The adult human pubic symphysis: a systematic review". Journal of Anatomy. 217 (5): 475–87. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01300.x. PMC 3035856. PMID 20840351.

- da Rocha, RC; Chopard, RP (March 2004). "Nutrition pathways to the symphysis pubis". Journal of Anatomy. 204 (3): 209–215. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00271.x. PMC 1571274. PMID 15032910.

- Gamble, J.G.; Simmons, S.C. (February 1986). "The Symphysis Pubis: Anatomic and Pathologic Considerations". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 203 (203): 261–272. doi:10.1097/00003086-198602000-00033. PMID 3955988.

- Lebel, D.E.; et al. (2010). "Symphysiolysis as an independent risk factor for cesarean delivery". Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 23 (5): 417–420. doi:10.3109/14767050903420291. PMID 20199196. S2CID 42116716.

- "Pubic symphysis separation". Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review (2002), 13: 141-155 Kelly Owens, Anne Pearson, Gerald Mason.

- "Pubic Symphysial Diastasis During Normal Vaginal Delivery of a", Journal of Obste India Vol. 55 No. 4 July/August 2005 pp:365-366 S. A. Panditrao et al.

- Scicluna, J.K.; et al. (January 2004). "Epidural analgesia for acute symphysis pubis dysfunction in the second trimester". International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesiology. 13 (1): 50–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2003.08.006. PMID 15321442.

- Wu, W.H.; et al. (2004). "Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence". European Spine Journal. 13 (7): 575–589. doi:10.1007/s00586-003-0615-y. PMC 3476662. PMID 15338362.

- Obstetrics and Gynaecology in The Tropics and Developing Countries. J. B. Lawson, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria; D. B. Stewart, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of The West Indies, Jamaica

- Hope Langer, MD; New York Times Review of Books, 22 October 2006

- Franklin, D (January 2010). "Forensic age estimation in human skeletal remains: current concepts and future directions". Legal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 12 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.09.001. PMID 19853490.

External links

- Pelvic Instability Network Support (PINS)

- Anatomy photo:17:st-0206 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Major Joints of the Lower Extremity – hip and sacrum (anterior view)"

- Anatomy photo:44:03-0104 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "The Male Pelvis: Hemisection of the Male Pelvis"

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna