Pulsejet

A pulsejet engine (or pulse jet) is a type of jet engine in which combustion occurs in pulses. A pulsejet engine can be made with few[1] or no moving parts,[2][3][4] and is capable of running statically (i.e. it does not need to have air forced into its inlet, typically by forward motion). The best known example may be the Argus As 109-014 used to propel Nazi Germany's V-1 flying bomb.

| Part of a series on |

| Aircraft propulsion |

|---|

|

Shaft engines: driving propellers, rotors, ducted fans or propfans |

| Reaction engines |

Pulsejet engines are a lightweight form of jet propulsion, but usually have a poor compression ratio, and hence give a low specific impulse.

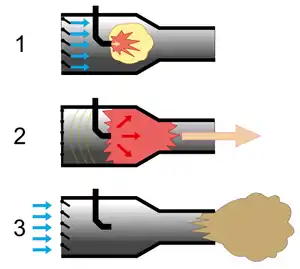

There are two main types of pulsejet engines, both of which use resonant combustion and harness the expanding combustion products to form a pulsating exhaust jet that produces thrust intermittently. The first is known as a valved or traditional pulsejet and it has a set of one-way valves through which the incoming air passes. When the air-fuel is ignited, these valves slam shut, which means that the hot gases can only leave through the engine's tailpipe, thus creating forward thrust. The second type of pulsejet is known as the valveless pulsejet.[5] Technically the term for this engine is the acoustic-type pulsejet, or aerodynamically valved pulsejet.

One notable line of research of pulsejet engines includes the pulse detonation engine, which involves repeated detonations in the engine, and which can potentially give high compression and reasonably good efficiency.

History

Russian inventor and retired artillery officer Nikolaj Afanasievich Teleshov patented a steam pulsejet engine in 1867 while Swedish inventor Martin Wiberg also has a claim to having invented the first pulsejet, in Sweden, but details are unclear.

The first working pulsejet was patented in 1906 by Russian engineer V.V. Karavodin, who completed a working model in 1907. The French inventor Georges Marconnet patented his valveless pulsejet engine in 1908, and Ramón Casanova, in Ripoll, Spain patented a pulsejet in Barcelona in 1917, having constructed one beginning in 1913. Robert Goddard invented a pulsejet engine in 1931, and demonstrated it on a jet-propelled bicycle.[6] Engineer Paul Schmidt pioneered a more efficient design based on modification of the intake valves (or flaps), earning him government support from the German Air Ministry in 1933.[7]

In 1909, Georges Marconnet developed the first pulsating combustor without valves. It was the grandfather of all valveless pulsejets. The valveless pulsejet was experimented with by the French propulsion research group SNECMA (Société Nationale d'Étude et de Construction de Moteurs d'Aviation ), in the late 1940s.

The valveless pulsejet's first widespread use was the Dutch drone Aviolanda AT-21[8]

Argus As 109-014

In 1934, Georg Hans Madelung and Munich-based Paul Schmidt proposed to the German Air Ministry a "flying bomb" powered by Schmidt's pulsejet. Madelung co-invented the ribbon parachute, a device used to stabilise the V-1 in its terminal dive. Schmidt's prototype bomb failed to meet German Air Ministry specifications, especially owing to poor accuracy, range and high cost. The original Schmidt design had the pulsejet placed in a fuselage like a modern jet fighter, unlike the eventual V-1, which had the engine placed above the warhead and fuselage.

The Argus Company began work based on Schmidt's work. Other German manufacturers working on similar pulsejets and flying bombs were The Askania Company, Robert Lusser of Fieseler, Dr. Fritz Gosslau of Argus and the Siemens company, which were all combined to work on the V-1.[7]

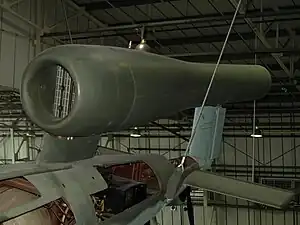

With Schmidt now working for Argus, the pulsejet was perfected and was officially known by its RLM designation as the Argus As 109-014. The first unpowered drop occurred at Peenemünde on 28 October 1942 and the first powered flight on 10 December 1942.

The pulsejet was evaluated to be an excellent balance of cost and function: a simple design that performed well for minimal cost.[7] It would run on any grade of petroleum and the ignition shutter system was not intended to last beyond the V-1's normal operational flight life of one hour. Although it generated insufficient thrust for takeoff, the V-1's resonant jet could operate while stationary on the launch ramp. The simple resonant design based on the ratio (8.7:1) of the diameter to the length of the exhaust pipe functioned to perpetuate the combustion cycle, and attained stable resonance frequency at 43 cycles per second. The engine produced 2,200 N (490 lbf) of static thrust and approximately 3,300 N (740 lbf) in flight.[7]

Ignition in the As 014 was provided by a single automotive spark plug, mounted approximately 75 cm (30 in) behind the front-mounted valve array. The spark only operated for the start sequence for the engine; the Argus As 014, like all pulsejets, did not require ignition coils or magnetos for ignition — the ignition source being the tail of the preceding fireball during the run. The engine casing did not provide sufficient heat to cause diesel-type ignition of the fuel, as there is insignificant compression within a pulsejet engine.

The Argus As 014 valve array was based on a shutter system that operated at the 43 to 45 cycles-per-second frequency of the engine.

Three air nozzles in the front of the Argus As 014 were connected to an external high pressure source to start the engine. The fuel used for ignition was acetylene, with the technicians having to place a baffle of wood or cardboard in the exhaust pipe to stop the acetylene diffusing before complete ignition. Once the engine ignited and minimum operating temperature was attained, external hoses and connectors were removed.

The V-1, being a cruise missile, lacked landing gear, instead the Argus As 014 was launched on an inclined ramp powered by a piston-driven steam catapult. Steam power to fire the piston was generated by the violent exothermic chemical reaction created when hydrogen peroxide and potassium permanganate (termed T-Stoff and Z-Stoff) are combined.

The principal military use of the pulsejet engine, with the volume production of the Argus As 014 unit (the first pulsejet engine ever in volume production), was for use with the V-1 flying bomb. The engine's characteristic droning noise earned it the nicknames "buzz bomb" or "doodlebug". The V-1 was a German cruise missile used in World War II, most famously in the bombing of London in 1944. Pulsejet engines, being cheap and easy to construct, were the obvious choice for the V-1's designers, given the Germans' materials shortages and overstretched industry at that stage of the war. Designers of modern cruise missiles do not choose pulsejet engines for propulsion, preferring turbojets or rocket engines. The only other uses of the pulsejet that reached the hardware stage in Nazi Germany were the Messerschmitt Me 328 and an experimental Einpersonenfluggerät project for the German Heer.

Wright Field technical personnel reverse-engineered the V-1 from the remains of one that had failed to detonate in Britain. The result was the creation of the JB-2 Loon, with the airframe built by Republic Aviation, and the Argus As 014 reproduction pulsejet powerplant, known by its PJ31 American designation, being made by the Ford Motor Company.

General Hap Arnold of the United States Army Air Forces was concerned that this weapon could be built of steel and wood, in 2000 man hours and approximate cost of US$600 (in 1943).[7]

Design

Pulsejet engines are characterized by simplicity, low cost of construction, and high noise levels. While the thrust-to-weight ratio is excellent, thrust specific fuel consumption is very poor. The pulsejet uses the Lenoir cycle, which, lacking an external compressive driver such as the Otto cycle's piston, or the Brayton cycle's compression turbine, drives compression with acoustic resonance in a tube. This limits the maximum pre-combustion pressure ratio, to around 1.2 to 1.

The high noise levels usually make them impractical for other than military and other similarly restricted applications.[8] However, pulsejets are used on a large scale as industrial drying systems, and there has been a resurgence in studying these engines for applications such as high-output heating, biomass conversion, and alternative energy systems, as pulsejets can run on almost anything that burns, including particulate fuels such as sawdust or coal powder.

Pulsejets have been used to power experimental helicopters, the engines being attached to the ends of the rotor blades. In providing power to helicopter rotors, pulsejets have the advantage over turbine or piston engines of not producing torque upon the fuselage since they don't apply force to the shaft, but push the tips. A helicopter may then be built without a tail rotor and its associated transmission and drive shaft, simplifying the aircraft (cyclic and collective control of the main rotor is still necessary). This concept was being considered as early as 1947 when the American Helicopter Company started work on its XA-5 Top Sergeant helicopter prototype powered by pulsejet engines at the rotor tips.[9] The XA-5 first flew in January 1949 and was followed by the XA-6 Buck Private with the same pulsejet design. Also in 1949 Hiller Helicopters built and tested the Hiller Powerblade, the world's first hot-cycle pressure-jet rotor. Hiller switched to tip mounted ramjets but American Helicopter went on to develop the XA-8 under a U.S. Army contract. It first flew in 1952 and was known as the XH-26 Jet Jeep. It used XPJ49 pulsejets mounted at the rotor tips. The XH-26 met all its main design objectives but the Army cancelled the project because of the unacceptable level of noise of the pulsejets and the fact that the drag of the pulsejets at the rotor tips made autorotation landings very problematic. Rotor-tip propulsion has been claimed to reduce the cost of production of rotary-wing craft to 1/10 of that for conventional powered rotary-wing aircraft.[8]

Pulsejets have also been used in both control-line and radio-controlled model aircraft. The speed record for control-line pulsejet-powered model aircraft is greater than 200 miles per hour (323 km/h).

The speed of a free-flying radio-controlled pulsejet is limited by the engine's intake design. At around 450 km/h (280 mph) most valved engines' valve systems stop fully closing owing to ram air pressure, which results in performance loss.

Variable intake geometry lets the engine produce full power at most speeds by optimizing for whatever speed at which the air enters the pulsejet. Valveless designs are not as negatively affected by ram air pressure as other designs, as they were never intended to stop the flow out of the intake, and can significantly increase in power at speed.

Another feature of pulsejet engines is that their thrust can be increased by a specially shaped duct placed behind the engine. The duct acts as an annular wing, which evens out the pulsating thrust, by harnessing aerodynamic forces in the pulsejet exhaust. The duct, typically called an augmentor, can significantly increase the thrust of a pulsejet with no additional fuel consumption. Gains of 100% increases in thrust are possible, resulting in a much higher fuel efficiency. However, the larger the augmenter duct, the more drag it produces, and it is only effective within specific speed ranges.

Operation

Valved designs

Valved pulsejet engines use a mechanical valve to control the flow of expanding exhaust, forcing the hot gas to go out of the back of the engine through the tailpipe only, and allow fresh air and more fuel to enter through the intake as the inertia of the escaping exhaust creates a partial vacuum for a fraction of a second after each detonation. This draws in additional air and fuel between pulses.

The valved pulsejet comprises an intake with a one-way valve arrangement. The valves prevent the explosive gas of the ignited fuel mixture in the combustion chamber from exiting and disrupting the intake airflow, although with all practical valved pulsejets there is some 'blowback' while running statically or at low speed, as the valves cannot close fast enough to prevent some gas from exiting through the intake. The superheated exhaust gases exit through an acoustically resonant exhaust pipe.

The intake valve is typically a reed valve. The two most common configurations are the daisy valve, and the rectangular valve grid. A daisy valve consists of a thin sheet of material to act as the reed, cut into the shape of a stylized daisy with "petals" that widen towards their ends. Each "petal" covers a circular intake hole at its tip. The daisy valve is bolted to the manifold through its centre. Although easier to construct on a small scale, it is less effective than a valve grid.

The cycle frequency is primarily dependent on the length of the engine. For a small model-type engine the frequency may be around 250 pulses per second, whereas for a larger engine such as the one used on the German V-1 flying bomb, the frequency was closer to 45 pulses per second. The low-frequency sound produced resulted in the missiles being nicknamed "buzz bombs."

Valveless designs

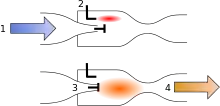

Valveless pulsejet engines have no moving parts and use only their geometry to control the flow of exhaust out of the engine. Valveless pulsejets expel exhaust out of both the intakes and the exhaust, but the majority of the force produced leaves through the wider cross section of the exhaust. The larger amount of mass leaving the wider exhaust has more inertia than the backwards flow out of the intake, allowing it to produce a partial vacuum for a fraction of a second after each detonation, reversing the flow of the intake to its proper direction, and therefore ingesting more air and fuel. This happens dozens of times per second.

The valveless pulsejet operates on the same principle as the valved pulsejet, but the 'valve' is the engine's geometry. Fuel, as a gas or atomized liquid spray, is either mixed with the air in the intake or directly injected into the combustion chamber. Starting the engine usually requires forced air and an ignition source, such as a spark plug, for the fuel-air mix. With modern manufactured engine designs, almost any design can be made to be self-starting by providing the engine with fuel and an ignition spark, starting the engine with no compressed air. Once running, the engine only requires input of fuel to maintain a self-sustaining combustion cycle.

The combustion cycle comprises five or six phases depending on the engine: Induction, Compression, (optional) Fuel Injection, Ignition, Combustion, and Exhaust.

Starting with ignition within the combustion chamber, a high pressure is raised by the combustion of the fuel-air mixture. The pressurized gas from combustion cannot exit forward through the one-way intake valve and so exits only to the rear through the exhaust tube.

The inertial reaction of this gas flow causes the engine to provide thrust, this force being used to propel an airframe or a rotor blade. The inertia of the traveling exhaust gas causes a low pressure in the combustion chamber. This pressure is less than the inlet pressure (upstream of the one-way valve), and so the induction phase of the cycle begins.

In the simplest of pulsejet engines this intake is through a venturi, which causes fuel to be drawn from a fuel supply. In more complex engines the fuel may be injected directly into the combustion chamber. When the induction phase is under way, fuel in atomized form is injected into the combustion chamber to fill the vacuum formed by the departing of the previous fireball; the atomized fuel tries to fill up the entire tube including the tailpipe. This causes atomized fuel at the rear of the combustion chamber to "flash" as it comes in contact with the hot gases of the preceding column of gas—this resulting flash "slams" the reed-valves shut or in the case of valveless designs, stops the flow of fuel until a vacuum is formed and the cycle repeats.

Valveless pulsejets come in a number of shapes and sizes, with different designs being suited for different functions. A typical valveless engine will have one or more intake tubes, a combustion chamber section, and one or more exhaust tube sections.

The intake tube takes in air and mixes it with fuel to combust, and also controls the expulsion of exhaust gas, like a valve, limiting the flow but not stopping it altogether. While the fuel-air mixture burns, most of the expanding gas is forced out of the exhaust pipe of the engine. Because the intake tube(s) also expel gas during the exhaust cycle of the engine, most valveless engines have the intakes facing backwards so that the thrust created adds to the overall thrust, rather than reducing it.

The combustion creates two pressure wave fronts, one traveling down the longer exhaust tube and one down the short intake tube. By properly 'tuning' the system (by designing the engine dimensions properly), a resonating combustion process can be achieved.

While some valveless engines are known for being extremely fuel-hungry, other designs use significantly less fuel than a valved pulsejet, and a properly designed system with advanced components and techniques can rival or exceed the fuel efficiency of small turbojet engines.

A properly designed valveless engine will excel in flight as it does not have valves, and ram air pressure from traveling at high speed does not cause the engine to stop running like a valved engine. They can achieve higher top speeds, with some advanced designs being capable of operating at Mach .7 or possibly higher.

The advantage of the acoustic-type pulsejet is simplicity. Since there are no moving parts to wear out, they are easier to maintain and simpler to construct.

Future uses

Pulsejets are used today in target drone aircraft, flying control line model aircraft (as well as radio-controlled aircraft), fog generators, and industrial drying and home heating equipment. Because pulsejets are an efficient and simple way to convert fuel into heat, experimenters are using them for new industrial applications such as biomass fuel conversion, and boiler and heater systems.

Some experimenters continue to work on improved designs. The engines are difficult to integrate into commercial crewed aircraft designs because of noise and vibration, though they excel on the smaller-scale uncrewed vehicles.

The pulse detonation engine (PDE) marks a new approach towards non-continuous jet engines and promises higher fuel efficiency compared to turbofan jet engines, at least at very high speeds. Pratt & Whitney and General Electric now have active PDE research programs. Most PDE research programs use pulsejet engines for testing ideas early in the design phase.

Boeing has a proprietary pulsejet engine technology called Pulse Ejector Thrust Augmentor (PETA), which proposes to use pulsejet engines for vertical lift in military and commercial VTOL aircraft.[10]

References

- "Pulse Detonation Engine". Gofurther.utsi.edu. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Google News". Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Patent US6216446 – Valveless pulse-jet engine with forward facing intake duct – Google Patents". Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Valveless Pulsjet". Home.no. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Geng, T.; Schoen, M. A.; Kuznetsov, A. V.; Roberts, W. L. (2007). "Combined Numerical and Experimental Investigation of a 15-cm Valveless Pulsejet". Flow, Turbulence and Combustion. 78 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1007/s10494-006-9032-8. S2CID 122906134.

- U.S. Patent 1,980,266

- George Mindling, Robert Bolton: US Airforce Tactical Missiles:1949–1969: The Pioneers, Lulu.com, 200: ISBN 0-557-00029-7. pp6-31

- Jan Roskam, Chuan-Tau Edward Lan; Airplane aerodynamics and performance, DARcorporation: 1997, ISBN 1-884885-44-6, 711 pages

- "Excerpt of Flight May 12, 1949" (PDF). flightglobal.com. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Diaz, Jesus (28 July 2011). "Boeing's Millennium Falcon Floats Using Nazi Technology". Wired.

Further reading

- Aeronautical Engineering Review, Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences (U.S.): 1948, vol. 7.

- George Mindling, Robert Bolton: US Airforce Tactical Missiles:1949–1969: The Pioneers, Lulu.com, 200: ISBN 0-557-00029-7. pp6–31

External links

- pulse-jets.com: An international site dedicated to pulsejets, including design and experimentation. Includes an extremely active forum composed of knowledgeable enthusiasts

- Video of 21st century-built German reproduction Argus As 014 pulsejet testing

- Pulsejets in aeromodels

- Popular Rotocraft Association Archived 7 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Pulsejet Bike

- Apocalyptic robotics performance group Survival Research Labs operates a collection of pulsejet engines in some of their creations, including the Hovercraft, V1, and the Flame Hurricane.

- PETA (Pulse-Ejector-Thrust-Augmentors) article

- Ramon Casanova's pulsejet

- American Helicopter XA-5 Flight

- PULSE JET ENGINE CAN BE USE IN BICYCLE TO RUN IT AT HIGH SPEED USING U-SHAPE TUBE

- Pulse jet designs and valveless pulsejet configurations

- Interaction behaviour of pulsejet engines

- Theoretical and Experimental Evaluation of Pulse Jet Engine

- US Air Force funds development of pulsejet powered air decoy