Punjabi festivals

Punjabi festivals are various festive celebrations observed by Punjabis in Pakistan, India and the diaspora Punjabi community found worldwide. The Punjabis are a diverse group of people from different religious background that affects the festivals they observe. According to a 2007 estimate, the total population of Punjabi Muslims is about 90 million (~75% of all Punjabis), with 97% of Punjabis who live in Pakistan following Islam, in contrast to the remaining 30 million Punjabi Sikhs and Punjabi Hindus who predominantly live in India.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Punjabis |

|---|

|

_with_cities.png.webp) Punjab portal |

The Punjabi Muslims typically observe the Islamic festivals, do not observe Hindu or Sikh religious festivals, and in Pakistan the official holidays recognize only the Islamic festivals.[2][3] The Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus typically do not observe these, and instead observe historic festivals such as Lohri, Basant and Vaisakhi as seasonal festivals.[4] The Sikh and Hindu festivals are regional official holidays in India, as are major Islamic festivals.[5] Other seasonal Punjabi festivals in India include Teejon (Teeyan) and Maghi.[4] Teeyan is also known as festival of women, as women enjoy it with their friends. On the day of maghi people fly kites and eat their traditional dish khichdi.

The Punjabi Muslim festivals are set according to the lunar Islamic calendar (Hijri), and the date falls earlier by 10 to 13 days from year to year.[6] The Hindu and Sikh Punjabi seasonal festivals are set on specific dates of the luni-solar Bikrami calendar or Punjabi calendar and the date of the festival also typically varies in the Gregorian calendar but stays within the same two Gregorian months.[7]

Some Punjabi Muslims participate in the traditional, seasonal festivals of the Punjab region: Baisakhi, Basant and to a minor scale Lohri, but this is controversial. Islamic clerics and some politicians have attempted to ban this participation because of the religious basis of the Punjabi festivals,[8] and they being declared haram (forbidden in Islam).[9]

Buddhist festivals

Punjabi Buddhists are a minority in Punjab, India.[10] In the Punjab province of Pakistan, the Buddhist population is negligible.[11]

Punjabi Buddhists celebrate festivals such as Buddha Jayanti.[12]

Christian Festivals

Christians are a minority in Pakistan, constituting about 2.3% of its population in contrast to 97.2% Muslims.[11] In Indian state of Punjab, Christians form about 1.1% of its total population, while the predominant majority of the population being Sikh and Hindus. Punjabi Christians celebrate Christmas to mark the birth of Jesus. In Punjab, Pakistan, people stay up late singing Punjabi Christmas carol services.[13] People attend churches in places such as Gurdaspur, Amritsar, Jalandhar and Hoshiarpur districts in Punjab, India that have a higher Christian population, to be part of Christmas celebrations.[14] Christians also celebrate Easter by engaging in processions.[15]

Hindu festivals

Punjabi Hindus celebrate a number of religious festivals.

Bavan Dvadasi

Bavan Dvadasi is a festival dedicated to the Hindu God Vamana. The festival is held during the lunar month of Bhadra. Singh writing for the Tribune in 2000 states that "Tipri, a local version of dandia of Gujarat and a characteristic of the Patiala and Ambala districts, is losing popularity. Its performances are now limited to the occasions of Bavan Dvadsi." According to Singh (2000) "Bavan Dvadsi is a local festival celebrated only in the Patiala and Ambala districts. Anywhere else, people are not aware of it. Now, tipri is performed during this festival only." Singh then states that Bavan Dvadsi "is to celebrate the victory of Lord Vishnu, who in the form of a dwarf, had tricked Raja Bali to grant him three wishes, before transforming into a giant to take the Earth, the sky and Bali's life". Tripri competitions are held during the festival. Dancers dance in pairs, striking the sticks and creating a rhythm whilst holding ropes.[16]

Raksha Bandhan

Raksha Bandhan, also Rakshabandhan, or Rakhi,[17][18] is a popular, traditionally Hindu, annual rite, or ceremony, which is central to a festival of the same name, celebrated in India, Nepal and other parts of the Indian subcontinent, and among people around the world influenced by Hindu culture. On this day, sisters of all ages tie a talisman, or amulet, called the rakhi, around the wrists of their brothers, symbolically protecting them, receiving a gift in return, and traditionally investing the brothers with a share of the responsibility of their potential care.[19]

Raksha Bandhan is observed on the last day of the Hindu lunar calendar month of Shraavana, which typically falls in August. The expression "Raksha Bandhan," Sanskrit, literally, "the bond of protection, obligation, or care," is now principally applied to this ritual. Until the mid-20th-century, the expression was more commonly applied to a similar ritual, also held on the same day, with precedence in ancient Hindu texts, in which a domestic priest ties amulets, charms, or threads on the wrists of his patrons, or changes their sacred thread, and receives gifts of money; in some places, this is still the case.[20][21] In contrast, the sister-brother festival, with origins in folk culture, had names which varied with location, with some rendered as Saluno,[22][23] Silono[24] and Rakri.[20] A ritual associated with included the sisters placing shoots of barley behind the ears of their brothers.[22]

Of special significance to married women, Raksha Bandhan is rooted in the practice of territorial or village exogamy, in which a bride marries out of her natal village or town, and her parents, by custom, do not visit her in her married home.[25] In rural north India, where village exogamy is strongly prevalent, large numbers of married Hindu women travel back to their parents' homes every year for the ceremony.[26][27] Their brothers, who typically live with the parents or nearby, sometimes travel to their sisters' married home to escort them back. Many younger married women arrive a few weeks earlier at their natal homes and stay until the ceremony.[28] The brothers serve as lifelong intermediaries between their sisters' married and parental homes,[29] as well as potential stewards of their security.

In urban India, where families are increasingly nuclear, the festival has become more symbolic, but continues to be highly popular. The rituals associated with this festival have spread beyond their traditional regions and have been transformed through technology and migration,[30] the movies,[31] social interaction,[32] and promotion by Hinduism,[33][34] as well as by the nation state.[35]

Among women and men who are not blood relatives, there is also a transformed tradition of voluntary kin relations, achieved through the tying of rakhi amulets, which have cut across caste and class lines,[36] and Hindu and Muslim divisions.[37] In some communities or contexts, other figures, such as a matriarch, or a person in authority, can be included in the ceremony in ritual acknowledgement of their benefaction.[38]

Krishna Janmashtami

Krishna Janmashtami, also known simply as Janmashtami or Gokulashtami, is an annual Hindu festival that celebrates the birth of Krishna, the eighth avatar of Vishnu.[39] It is observed according to the Hindu lunisolar calendar, on the eighth day (Ashtami) of the Krishna Paksha (dark fortnight) in Shraavana or Bhadrapad (depending on whether the calendar chooses the new moon or full moon day as the last day of the month), which overlaps with August or September of the Gregorian calendar.[39]

It is an important festival, particularly in the Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism.[40] Dance-drama enactments of the life of Krishna according to the Bhagavata Purana (such as Rasa Lila or Krishna Lila), devotional singing through the midnight when Krishna was born, fasting (upavasa), a night vigil (Ratri Jagaran), and a festival (Mahotsav) on the following day are a part of the Janmashtami celebrations.[41] It is celebrated particularly in Mathura and Vrindavan, along with major Vaishnava and non-sectarian communities found in Manipur, Assam, Bihar, West Bengal, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and all other states of India.[39][42]

Krishna Janmashtami is followed by the festival Nandotsav, which celebrates the occasion when Nanda Baba distributed gifts to the community in honor of the birth.[43]

Mahashivratri

Maha Shivaratri is the great night of Shiva, during which followers of Shiva observe religious fasting and the offering of Bael (Bilva) leaves to Shiva. Mahashivaratri Festival or ‘The Night of Shiva’ is celebrated with devotion and religious fervor in honor of Lord Shiva, one of the deities of Hindu Trinity. Shivaratri falls on the moonless 14th night of the new moon in Phalgun (February – March). Celebrating the festival of Shivaratri devotees observe day and night fast and perform ritual worship of Shiva Lingam to appease Lord Shiva. To mark the Shivratri festival, devotees wake up early and take a ritual bath, preferably in river Ganga. After wearing fresh new clothes devotees visit the nearest Shiva temple to give ritual bath to the Shiva Lingum with milk, honey, water etc. On Shivaratri, worship of Lord Shiva continues all through the day and night. Every three hours priests perform ritual pooja of Shivalingam by bathing it with milk, yoghurt, honey, ghee, sugar and water amidst the chanting of “Om Namah Shivaya’ and ringing of temple bells. Jaagran (Nightlong vigil) is also observed in Shiva temples where large number of devotees spend the night singing hymns and devotional songs in praise of Lord Shiva. It is only on the following morning that devotee break their fast by partaking prasad offered to the deity.[44]

Holi

Holi is the spring Hindu festival of colours which is celebrated by throwing colours on each other.[45][46] The festival is celebrated on the full moon day of Phalguna Month[47] of Hindu Calendar. The festival is primarily celebrated by Hindus and Sikhs.[48]

In the Indian state of Punjab, Holi is preceded by Holika Dahan the night before. On the day of Holi, people engage in throwing colours[49] on each other.[50]

During Holi in Punjab, walls and courtyards of rural houses are enhanced with drawings and paintings similar to rangoli in South India, mandana in Rajasthan, and rural arts in other parts of India. This art is known as chowk-poorana or chowkpurana in Punjab and is given shape by the peasant women of the state. In courtyards, this art is drawn using a piece of cloth. The art includes drawing tree motifs, flowers, ferns, creepers, plants, peacocks, palanquins, geometric patterns along with vertical, horizontal and oblique lines. These arts add to the festive atmosphere.[51]

Sanjhi

Sanjhi is celebrated mainly by women and girls in parts of Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh.[52] Sanjhi is the name of a mother goddess, after whom images are made of mud and molded into various shapes such as cosmic bodies or the face of the goddess, and they get different colors. The local potters make images of various body parts like her arms, legs, face decked with ornaments and weapons. These additions make the image look beautiful and gracious. The additions to the image this way depend upon the economic means of the family.[53]

The image is designed on the first day of the nine days of Durga Puja or Navratri. Every day women from the neighborhood are invited for singing bhajans and performing aarti. The young girls also gather there and offer their adoration to the mother who is believed to get them suitable husbands. The aarti or the bhajans are chanted daily and some elderly woman guides others. It is usually an all females event. Sanjhi image is prepared on the wall by those families who seek fulfillment of their wishes termed mannat by Punjabis. Some people also seek her blessings for the marriage of their daughters. Kirtan is performed and the image is immersed in water on the last day. The Sanjhi festival ends with the immersion of Sanjhi on the day of Dussehra.[54] The girls offer prayers and food to the goddess every day.

Maghi

Maghi is the regional name of Makar Sankranti or Magh Sankranti[47] and marks beginning of Magha month of Hindu Calendar.[55] While Hindus gather near Mandirs.[56] The Magha Mela, according to Diana L. Eck – a professor at Harvard University specializing in Indology, is mentioned in the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, thus placing this festival to be around 2,000 years old.[57] Many go to sacred rivers or lakes and bathe with thanksgiving to the sun.[57] Maghi happens to be the day when Bhishma, the octogenarian leader of Kauravas emacipated his soul from bondage of body, by conscious act of will after discoursing many days on mysteries of life and death.[58]

Vaisakhi

Vaisakhi, also pronounced as Baisakhi marks the beginning of Hindu solar New year.[59][60] Vaisakhi marks the first day of the month of Vaisakha and is usually celebrated on 13 or 14 April every year. This holiday also is known as Vaisakha Sankranti and celebrates the Solar new year, based on the Hindu Vikram Samvat calendar.

Vaisakhi is a historical and religious festival in Hinduism. It is usually celebrated on 13 or 14 April every year.[61][62] For Hindus, the festival is their traditional solar new year, a harvest festival, an occasion to bath in sacred rivers such as Ganges, Jhelum, and Kaveri, visit temples, meet friends and take part in other festivities. In other parts of India, the Vaisakhi festival is known by various regional names.[63]

In Undivided Punjab, the Hindu Shrine of Katas Raj was known for its Vaisakhi fair.[64] It was attended by around 10,000 pilgrims who were mostly Hindus.[65] Similarly, at the shrine of Bairagi Baba Ram Thaman, a Vaisakhi fair was held annually since 16th century CE which was attended by around 60,000 pilgrims and Bairagi saints from all over India used to throng the shrine.[66][67]

The Vaisakhi fair is at Thakurdwara Bhagwan Narainji at Pandori Mahatan village in Gurdaspur district of Punjab where the fair lasts for three days from 1st Vaisakha to 3rd Vaisakha.[68] The celebrations start in form of procession on morning of 1st Vaisakha, carrying Mahant in a palanquin by Brahmacharis and devotees. After that Navgraha Puja is held and charities in money, grains and cows are done.[69] At evening, Sankirtan is held in which Mahant delivers religious discourses and concludes it by distributing prasad of Patashas (candy drops). Pilgrims also take ritual bathings at sacred tank in the shrine.[70][68]

Ram Navami

Rama Navami is the celebration of the birth of Rama. Rama Navami is the day on which Lord Rama, the seventh incarnation of Lord Vishnu, incarnated in human form in Ayodhya. He is the ardha ansh of Vishnu or has half the divinitive qualities of Lord Vishnu. The word “Rama” literally means one who is divinely blissful and who gives joy to others, and one in whom the sages rejoice. Ram Navami falls on the ninth day of the bright fortnight in Chaitra (April/May) and coincides with Vasant Navratri or Chait Durga Puja. Therefore, in some regions, the festival is spread over nine days. This day, marking the birthday of Lord Rama, is also observed as the marriage day of Rama and Sita and thus also referred to as Kalyanotsavam. In Ayodhya, the birthplace of Lord Rama, a huge fair is held with thousands of devotees gathering to celebrate this festival. The fair continues for two days, and rathyatras, carrying the Deities of Ram, his brother Laxman, His wife Sita, and His greatest devotee Mahavir Hanuman, are taken out from almost all Ram Temples. Hanuman is known for is his devotion to Rama, and his tales form an important part of the celebration. In Andhra Pradesh, Ram Navami is celebrated for 10 days from the Chaitra saptami to the Bahula Padyami in March/April. Temples re-enact the marriage of Lord Rama and Sita to commemorate this event, since this day is also the day they got married.[71]

Dussehra

In most of northern and western India, Dasha-Hara (literally, "ten days") is celebrated in honour of Rama. Thousands of drama-dance-music plays based on the Ramayan and Ramcharitmanas (Ramlila) are performed at outdoor fairs across the land and in temporarily built staging grounds featuring effigies of the demons Ravan, Kumbhakarna and Meghanada. The effigies are burnt on bonfires in the evening of Vijayadashami-Dussehra.[72] While Dussehra is observed on the same day across India, the festivities leading to it vary. In many places, the "Rama Lila" or the brief version of the story of Rama, Sita and Lakshaman, is enacted over the 9 days before it, but in some cities, such as Varanasi, the entire story is freely acted out by performance-artists before the public every evening for a month.[73]

The performance arts tradition during the Dussehra festival was inscribed by UNESCO as one of the "Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity" in 2008.[74] The festivities, states UNESCO, include songs, narration, recital and dialogue based on the Hindu text Ramacharitmanas by Tulsidas. It is celebrated across northern India for Dussehra, but particularly in historically important Hindu cities of Ayodhya, Varanasi, Vrindavan, Almora, Satna and Madhubani.[74] The festival and dramatic enactment of the virtues versus vices filled story is organised by communities in hundreds of small villages and towns, attracting a mix of audiences from different social, gender and economic backgrounds. In many parts of India, the audience and villagers join in and participate spontaneously, helping the artists, others helping with stage setup, make-up, effigies, and lights.[74] These arts come to a close on the night of Dussehra, when the victory of Rama is celebrated by burning the effigies of evil Ravan and his colleagues.[75]

Diwali

Diwali festival usually lasts five days and is celebrated during the Hindu lunisolar month Kartika (between mid-October and mid-November).[77][78][79] One of the most popular festivals of Hinduism, Diwali symbolizes the spiritual "victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance".[80][81][82][83] The festival is widely associated with Lakshmi, goddess of prosperity, with many other regional traditions connecting the holiday to Sita and Rama, Vishnu, Krishna, Yama, Yami, Durga, Kali, Hanuman, Ganesha, Kubera, Dhanvantari, or Vishvakarman. Furthermore, it is, in some regions, a celebration of the day Lord Rama returned to his kingdom Ayodhya with his wife Sita and his brother Lakshmana after defeating Ravana in Lanka and serving 14 years of exile.

In the lead-up to Diwali, celebrants will prepare by cleaning, renovating, and decorating their homes and workplaces with diyas (oil lamps) and rangolis.[84] During Diwali, people wear their finest clothes, illuminate the interior and exterior of their homes with diyas and rangoli, perform worship ceremonies of Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity and wealth,[note 1] light fireworks, and partake in family feasts, where mithai (sweets) and gifts are shared. Diwali is also a major cultural event for the Hindu and Jain diaspora from the Indian subcontinent.[87][88][89]

The five-day long festival originated in the Indian subcontinent and is mentioned in early Sanskrit texts. Diwali is usually celebrated twenty days after the Dashera (Dasara, Dasain) festival, with Dhanteras, or the regional equivalent, marking the first day of the festival when celebrants prepare by cleaning their homes and making decorations on the floor, such as rangolis.[90] The second day is Naraka Chaturdashi. The third day is the day of Lakshmi Puja and the darkest night of the traditional month. In some parts of India, the day after Lakshmi Puja is marked with the Govardhan Puja and Balipratipada (Padwa). Some Hindu communities mark the last day as Bhai Dooj or the regional equivalent, which is dedicated to the bond between sister and brother,[91] while other Hindu and Sikh craftsmen communities mark this day as Vishwakarma Puja and observe it by performing maintenance in their work spaces and offering prayers.[92][93]

Karwa chauth

Karu-ay is the Punjabi name for the fast of Karva Chauth.[94] This fast is primarily traditionally observed in the Punjab region but is also observed in parts of Uttar Pradesh[95] and Rajasthan.

Although the mode of performing the Karva Chauth fast requires the woman to see the moon through a sieve and then her husband's face through the same sieve before she eats, in the Punjabi Karu-ay da varat, traditionally a brother will collect his married sister who will keep the fast at her natal home.[94]

The women will eat sweet dishes before sunrise and will not eat throughout the day. Women also get dressed up in traditional attire and gather in the evening for hearing tales about the fast. The purpose of the fast is for the well-being and longevity of husbands.[94]

Jhakrya

Jhakrya is a Punjabi fast which according to Kehal is observed by mothers for their sons' well-being. However, Pritam (1996) believes the fast is kept by mothers for the welfare of their children.[96]

Jharkri is a clay pot in which dry sweet dishes are kept. Mothers are required to eat something sweet in the morning and then fast all day. Jhakrya fast is observed four days after Karva Chauth and is related to Hoi Mata. A mother who keeps Jhakrya da varat for the first time will distribute the sweets kept in the Jhakri to her husband's clan. She will also give her mother-in-law a Punjabi suit.

On subsequent fasts, mothers will fill the Jhakri will water and jaggery and rice. When the moon rises, an offering is made to the stars and then the sons. Other food will also be given to the sons. Thereafter, mothers will eat something sweet to break the fast.[97]

Ahoi Ashtami is a Hindu festival celebrated about 8 days before Diwali on Krishna Paksha Ashtami. According to Purnimant calendar followed in North India, it falls during the month of Kartik and according to Amanta calendar followed in Gujarat, Maharashtra and other southern states, it falls during the month of Ashvin. However, it is just the name of the month which differs and the fasting of Ahoi Ashtami is done on the same day.

The fasting and puja on Ahoi Ashtami are dedicated to Mata Ahoi or Goddess Ahoi. She is worshiped by mothers for the well-being and long life of their children. This day is also known as Ahoi Aathe because fasting for Ahoi Ashtami is done during Ashtami Tithi which is the eighth day of the lunar month. Ahoi Mata is none other than Goddess Parvati.

Bhoogay

Bhoogay falls on the fourth day of the first half of the lunar month of Poh. The day is also called Sankat Chauth.[98] The fast is kept by sisters for the well-being of brothers during the Punjabi month of Poh (December–January). Sisters will break their fast by eating sweet balls made of sesame, jaggery and flour Pinni.[94]

Sikh Festivals

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

The following religious festivals are observed by Sikhs.

Muktsar Mela

This festival commemorates the Battle of Muktsar where the Chalis Mukte or the forty beloved died. Guru Gobind Singh Ji commemorated the martyrs by holding a gathering and performing Kirtan.

The Maghi fair is held to honour the memory of the forty Sikh warriors killed during the Battle of Muktsar in 1705. Muktsar, originally called Khidrana, was named as Muktsar ("the pool of liberation") following the battle. These forty Sikhs, led by their leader Mahan Singh, had formally deserted Sri Guru Gobind Singh in the need of hour, and signed a written memorandum to the effect.[99] When Mai Bhago, a valiant and upright lady, heard of this cowardly act, she scolded the Singh's and inspired them refresh with spirit of bravery for which Sikhs are known. Hence, the unit went back and joined the Guru who was already engaged in action at Khidrana. All forty of them attained martyrdom. The memorandum (bedawa) was torn-down by the Guru himself just before Mahan Singh died.

People gather from all over Punjab, even other parts of India to join the festival which is in fact spread over many days. Merchants display their wares for sale, which include from trinkets to high-end electronics, the weapons Nihangs bear and especially agricultural machinery (since most around are farmers). The country's biggest circuses, Apollo and Gemini, are there as a matter of rule, merry-go-rounds and giant wheels, and the famous Well of Death (trick motorcycling inside a consortium of wood planks) are there.

Parkash Utsav Dasveh Patshah

This festival's name, when translated, means the birth celebration of the 10th Divine Light, or Divine Knowledges. It commemorates the birth of Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh guru. The festival is one of the most widely celebrated event by Sikhs.

Gobind Singh was the only son of Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh guru, and Mata Gujri.[100] He was born in Patna on 22 December 1666, Bihar in the Sodhi Khatri family [101] while his father was visiting Bengal and Assam.[101] His birth name was Gobind Rai, and a shrine named Takht Sri Patna Harimandar Sahib marks the site of the house where he was born and spent the first four years of his life.[101] In 1670, his family returned to Punjab, and in March 1672 they moved to Chakk Nanaki in the Himalayan foothills of north India, called the Sivalik range, where he was schooled.[102]

Hola Mohalla

An annual festival of thousands held at Anandpur Sahib. It was started by Guru Gobind Singh as a gathering of Sikhs for military exercises and mock battles. The mock battles were followed by kirtan and valour poetry competitions. Today the Nihang Singhs carry on the martial tradition with mock battles and displays of swordsmanship and horse riding. There are also a number of darbars where kirtan is sung. It is celebrated by Sikhs across the world as 'Sikh Olympics' with events and competitions of swordsmanship, horse riding, Gatka (Sikh martial arts), falconry and others by Nihang Singhs.

Vaisakhi

In Punjab it is celebrated as the birth of the Khalsa brotherhood. It is celebrated at a large scale at Kesgarh Sahib, Anandpur Sahib. In India, U.K., Canada, United States, and other Sikh populated areas, people come together for a public mela or parade. The main part of the mela is where a local Sikh Temple (Gurdwara) has a beautiful Sikh themed float on which the Guru Granth Sahib is located and every one offers their respect by bowing with much reverence and fervour. To mark the celebrations, Sikh devotees generally attend the Gurudwara before dawn with flowers and offerings in hands. Processions through towns are also common. Vaisakhi is the day on which the Khalsa was born and Sikhs were given a clear identity and a code of conduct to live by, led by the 10th Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, who baptized the first Sikhs using sweet nectar called Amrit.

Martyrdom of Guru Arjan

The martyrdom anniversary of Guru Arjan, the fifth Guru, falls in June, the hottest month in India. He was tortured to death under the orders of Mughal Emperor, Jahangir, on the complaint of a Hindu banker Chandu Lal, who bore a personal enmity with Guru, at Lahore on 25 May 1606. Celebrations consist of Kirtan, Katha and Langar in the Gurdwara. Because of hot summer, chilled sweetened drink made from milk, sugar, essence and water is freely distributed in Gurdwaras and in neighborhoods to everybody irrespective of their religious belief as a sign and honour of the humble Guru who happily accepted his torture as a will of Waheguru and made no attempt to take any action.

Guru Nanak Gurpurab

On this day Guru Nanak was born in Nanakana Sahib, now situated in Pakistan. Every year Sikhs celebrate this day with large-scale gatherings. Candles, divas and lights are lit in Gurdwaras, in the honour of Guru along with fireworks. The birthday celebration usually lasts three days. Generally two days before the birthday, Akhand Path (forty-eight-hour non-stop reading of Guru Granth Sahib) is held in the Gurdwara. One day before the birthday, a procession is organized which is led by the Panj Pyares (Five Beloved Ones) and the Palki (Palanquin) of Sri Guru Granth Sahib and followed by teams of Ragis singing hymns, brass bands playing different tunes and devotees singing the chorus.

Sipanji

The Martyrdom of both the elder and younger Sahibzadas is a remembrance of the four young princes (sons of Guru Gobind Singh) who were martyred in late December. The two older sons, Sahibzade Ajit Singh and Jujhar Singh, were killed by Mughal soldiers during the battle of Chamkaur. Both the younger sons Sahibzade Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh, were executed after being captured. These Martyrs are observed 21 December and 26 December respectively.

Bandi Chhor Divas

Bandi Chhor Divas was celebrated when Guru Hargobind sahib ji was released from Gwalior prison with 52 Hindu kings and princes holding on to his robe or cape with 52 ropes.The guru let all 52 innocent rulers to safety without any signs of war or battle. In addition to Nagar keertan (a street procession) and an Akhand paath (a continuous reading of Guru Granth Sahib), Bandi Chhor (Shodh) Divas is celebrated with a fireworks display. The Sri Harmandir Sahib, as well as the whole complex, is festooned with thousands of shimmering lights. The gurdwara organizes continuous kirtan singing and special musicians. Sikhs consider this occasion as an important time to visit Gurdwaras and spend time with their families.[103]

Hindu and Sikh festivals

The following festivals are celebrated jointly by Hindus and Sikhs and members of other faiths as Punjabi seasonal/cultural celebrations.

Lohri

Lohri is a cultural festival but for some Hindus it is considered a religious festival in North West India,[104] the religious part being offerings made to sacred fire, Agni, lit on Lohri festival.[105] The offering consists of sesame, jaggery, peanuts and popcorns.[105] Besides Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs, Lohri is also celebrated by Dogras and other people of Jammu,[106] people of Haryana and people from western and southern half of Himachal Pradesh.[107] According to Chauhan (1995), all Punjabis, including Sikhs, Muslims and Christians celebrate Lohri in Punjab, India.[108] Lohri is celebrated on the last day of the month of Poh (Pausha).[109]

Many people believe the festival commemorates the passing of the winter solstice.[110][111][112] Lohri is observed the night before Makar Sankranti, also known as Maghi, and according to the solar part of the Lunisolar Punjabi calendar (variation of the Bikrami calendar) and typically falls about the same date every year (January 13).[113]

Lohri is an official gazetted holiday in the state of Punjab (India),[114] but it is not a holiday in Punjab (Pakistan).[115] It is, however, observed by Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims and Christians in Punjab, India and by some Punjabi Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and Christians in Pakistan as well.[116]

Maghi

The festival marks the increase in daylight.[117] Maghi is celebrated by ritual bathing in holy water bodies and performing Daan (charity).[118][119] Hindus will visit the Mandir and bathe is rivers and Sikhs will observe the day by visiting the Gurdwara and also bathe in rivers and pools to mark Mela Maghi. Punjabis will consume Khichdi (Boiled Rice and Lentil mixture) and Rauh di kheer which is rice pudding cooked in sugarcane juice on this occasion. Rauh Di Kheer is prepared in the evening before Maghi and is kept to cool. It is served cold next morning on Maghi with red-chilly mixed curd.[120] Fairs are held at many places on Maghi.[121]

Basant Panchami

Basant Panchami is an ancient Hindu spring festival dedicated to god Kama as well as goddess Saraswati.[122] Its link with the Hindu god of love and its traditions have led some scholars to call it "a Hindu form of Valentine's Day".[123][124] The traditional colour of the day is yellow and the dish of the day is saffron rice. People fly kites.[122][125]

In North India, and in the Punjab province of Pakistan, Basant is celebrated as a spring festival of kites.[126] The festival marks the commencement of the spring season. In the Punjab region (including the Punjab province of Pakistan), Basant Panchami has been a long established tradition of flying kites[127] and holding fairs.

Punjabi Muslims have treated parts of the festival as a cultural event. In Pakistan however kite flying has been banned starting in 2007 with officials stating that it uses dangerous, life-threatening substances on the strings.[128] The festival ban was confirmed by the Pakistan Punjab state chief minister Shehbaz Sharif in 2017. According to some analysts, "the festival was banned due to pressure from hardline religious and extremist groups like the Hafiz Saeed-led Jamaat-ud Dawah, which claimed the festival had “Hindu origins” and was “un-Islamic”.[129]

Vaisakhi

Vaisakhi is a religious festival of Sikhs. Vaisakhi marks the beginning of Sikh new year and the formation of the Khalsa.[130][131] Punjabi Muslims observe the new year according to the Islamic calendar. Vaisakhi is also a harvest festival for people of the Punjab region.[132] The harvest festival is celebrated by Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus.[133] In the Punjab, Vaisakhi marks the ripening of the rabi harvest.[134]

Vaisakhi additionally marks the Punjabi new year.[135] This day is observed as a thanksgiving day by farmers whereby farmers pay their tribute, thanking God for the abundant harvest and also praying for future prosperity.[136] Historically, during the early 20th century, Vaisakhi was a sacred day for Sikhs and Hindus and a secular festival for all Muslims and non-Muslims including Punjabi Christians.[137] In modern times, sometimes Christians participate in Baisakhi celebrations along with Sikhs and Hindus.[138]

According to Aziz-ud-din Ahmed, Lahore used to have Baisakhi Mela after the harvesting of the wheat crop in April. However, adds Ahmed, the city started losing its cultural vibrancy in the 1970s after Zia-ul-Haq came to power, and in recent years "the Pakistan Muslim League (N) government in Punjab banned kite flying through an official edict more under the pressure of those who want a puritanical version of Islam to be practiced in the name of religion than anything else".[139] Unlike the Indian state of Punjab that recognizes the Vaisakhi Sikh festival as an official holiday,[5] the festival is not an official holiday in Punjab or Sindh provinces of Pakistan where Islamic holidays are officially recognized instead.[2][3] However, On 8 April 2016, Punjabi Parchar at Alhamra (Lahore) organised a show called Visakhi mela, where the speakers pledged to "continue our struggle to keep the Punjabi culture alive" in Pakistan through events such as Visakhi Mela.[140] Elsewhere Besakhi fairs or melas are held in various places including Eminabad[141] and Dera Ghazi Khan.[142][note 2]

Aawat pauni

Aawat pauni is a tradition associated with harvesting, which involves people getting together to harvest the wheat. Drums are played while people work. At the end of the day, people sing dohay to the tunes of the drum.[146]

Fairs and dances

The harvest festival is also characterized by the folk dance, Bhangra which traditionally is a harvest dance.

Fairs or Melas (fair) are held in many parts of Punjab, India to mark the new year and the harvesting season. Vaisakhi fairs take place in various places, including Jammu City, Kathua, Udhampur, Reasi and Samba,[147] in the Pinjore complex near Chandigarh,[148] in Himachal Pradesh cities of Rewalsar, Shimla, Mandi and Prashar Lakes.

Teeyan

Teeyan welcomes the monsoon season and the festival officially starts of the day of Teej and last for 13 days. The seasonal festival involves women and girls dancing Gidha and visiting family. The festival is observed in Punjab, India as a cultural festival by all communities.

The festival is celebrated during the monsoon season from the third day of the lunar month of Sawan on the bright half, up to the full moon of sawan, by women. Married women go to their maternal house to participate in the festivities.[149][150] In the past, it was traditional for women to spend the whole month of Sawan with their parents.[149][151]

Teej is historically a Hindu festival, dedicated to Goddess Parvati and her union with Lord Shiva, one observed in northern, western, central and Himalayan regions of the Indian subcontinent.[152][153]

Rakhri

Rakhri or Rakhrhee (Punjabi: ਰੱਖੜੀ) is the Punjabi word for Rakhi and a festival observed by Hindus and Sikhs.[154][155][156] In the Punjab region, the festival of Raksha Bandhan is celebrated as Rakhrhya (Punjabi: ਰੱਖੜੀਆ).[157] Rakhrhya is observed on the same day of the lunar month of Sawan. It, like Raksha Bandhan, celebrates the relationship between brothers and sisters. Rakhri means “to protect” whereby a brother promises to look out for his sister and in return, a sister prays for the well-being of her brother. According to Fedorak (2006), the festival of Rakhri celebrates "the bonds between brothers and sisters".[158] Married women often travel back to their natal homes for the occasion.[159]

A Rakhri can also be tied on a cousin or an unrelated man. If a woman ties a Rakhri on the wrist of an unrelated man, their relationship is treated as any other brother and sister relationship would be. The festival is a siblings-day comparable to Mother's day/Father's day/Grandparents day etc.[160]

A sister will tie the Rakhri on her brother's wrist and her brother will traditionally give his sister a gift in exchange. Another feature of the celebration is the consumption of sweets.[161] There is no special ceremony but a sister will sing folk songs[162] and say something along the lines of:

ਸੂਰਜ ਛੱਡੀਆਂ ਰਿਸ਼ਮਾਂ

ਮੂਲੀ ਛੱਡਿਆਂ ਬੀਅ

ਭੈਣ ਨੇ ਬੰਨੀ ਰੱਖੜੀ

ਜੁਗ ਜੁਗ ਵੀਰਾ ਜੀਅ

[163]

Transliteration:

Suraj chhadya rishma

mooli chhadya bi

bhain ne banni rahkhree

jug jug veera ji

Muslim festivals

The following religious festivals are observed by Punjabi Muslims.

Eid ul-Adha

Eid ul-Adha is also known as Eid-ul-Azha. The festival is celebrated on the tenth day of the last Islamic month of Zilhij. Eid-ul-Azha occurs about two months after Eid-ul-Fitr. Eid-ul-Azha is celebrated to commemorate the occasion when the prophet Abraham was ready to sacrifice his son, Ismail, on God's command. Abraham was awarded by God by replacing Ismail with a goat. Muslims make pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca during this time.[164]

Animal sacrifice is a tradition offered by Muslims on this day.[165] Special markets are set up to deal with the increase in demand of animals. Cattle markets are set up in places such as Multan, (Punjab, Pakistan)[166] and goat markets in Ludhiana,[167] (Punjab, India). The children celebrate Eid ul-Adha and Eid ul-Fitr with great pump and show and receive gifts and Eidi (money) from parents and others.[168]

Eid-ul-Fitr

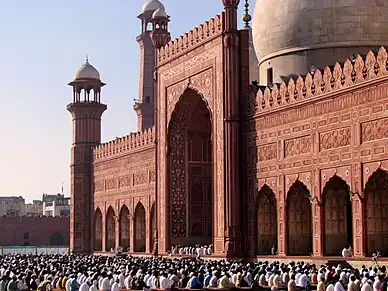

Eid al-Fitr takes place on the first day of the tenth month of the Islamic lunar calendar and celebrates the end of Ramadan. Ramadan is the time of fasting that continues throughout the ninth month.[169] On this day, after a month of fasting, Muslims express their joy and happiness by offering a congregational prayer in the mosques. Special celebration meals are served.[170] The festival is celebrated in Punjab, Pakistan. It is also celebrated in Malerkotla (Punjab, India) which has a sizable Muslim population where Sikhs and Hindus also participate in the observance.[171]

Eid-e-Milad-un-Nabi

Eid-e-Milad-un- Nabi is an Islamic festival which is celebrated in honour of the birth-day of Prophet Muhammad.[172] The festival is observed in the third month of the Islamic lunar calendar called Rabi'al-Awal.[173] Various processions take place in Lahore to celebrate the festival.[174] According to Nestorovic (2016), hundreds of thousands of people gather at Minare-Pakistan, Lahore, between the intervening night of 11th and 12th Rabi' al-awwal of the Islamic calendar Eid Milad Dun Nabi.[175] The festival was declared a national holiday in Pakistan in 1949.[176]

People from various places in Punjab, Pakistan including Bahawalpur, Faisalabad, Multan and Sargodha participate in processions and engage in decorating Mosques, streets and houses with green flags and lights.[177] According to Khalid, children, teenagers and young adults decorate their Pahari (mountain) of all sorts of toys, including cars, stereos, and numerous other commodities. Within various places of Lahore, there are numerous stalls. Before the festival became a celebratory day, people used to celebrate the day quietly. However, the first procession to mark the day was led from Delhi gate in Lahore in 1935. This tradition then became popular elsewhere.[178] Processions are also taken out in Bathinda (Punjab, India).[179]

Muharram

Remembrance of Muharram is a set of rituals associated with Shia,[180] which takes place in Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar. Many of the events associated with the ritual take place in congregation halls known as Hussainia. The event marks the anniversary of the Battle of Karbala when Imam Hussein ibn Ali, the grandson of Muhammad, was killed by the forces of the second Umayyad caliph Yazid I at Karbala. Family members, accompanying Hussein ibn Ali, were killed or subjected to humiliation. The commemoration of the event during yearly mourning season, from first of Muharram to twentieth of Safar with Ashura comprising the focal date, serves to define Shia communal identity.[181]

In Pakistani Punjab, Muharram is celebrated twice, once according to the Muslim year and again on the 10th of harh.[182]

Processions

Traditionally, a white horse representing Ali's white Mule Duldul, is usually lead in the Muharram procession, as in Jhang, Punjab, Pakistan.[183] Zuljanah, Tazia and Alam processions are observed in many places in Punjab, Pakistan including Sialkot, Gujranwala, Bahawalnagar, Sargodha, Bahawalpur.[184] and Lahore.

Zuljana

Zuljanah processions are held which involves taking a replica of a horse. The Zuljanah has two wings and the processions were introduced from Iran to Lahore during the 19th century.[185]

Tazia

Shia Muslims take out a Tazia procession on the day of Ashura. [186] A Tazia is traditionally a bamboo and paper model of Hussain's tomb at Karbala, which is carried in procession by Shias on the tenth day of the month of Muharram.[187] Moderns forms of Tazia can be more elaborate. Tazia processions in Punjab are historic and were observed during the Sikh and British period when the Tazia would be divided into many storeys, but not ordinarily more than three.[188] Such processions take place in Lahore where mourners take to the streets to commemorate the sacrifices of Imam Hussain and his family in Karbala. Various stalls are set up offering milk, water and tea along the route of the processions. Some distribute juice packets, dry fruit, sweetmeats and food among mourners.[189] Tazia processions can also be seen in Malerkotla[190] and Delhi.[191]

Alam

Alam processions take place in Punjab, Pakistan too.[192] Alam is an elaborate, heavy battle standard, carried by a standard bearer, alam-dar, ahead of the procession. It represents Imam Hussain's standard and is revered as a sacred object.[193]

Local festivals

Various local fairs and festivals are associated with particular shrines, temples and gurdwaras.

Mela Chiragan

Mela Chiraghan (Festival of Lights) is a three-day annual festival to mark the urs (death anniversary) of the Punjabi Sufi poet and saint Shah Hussain (1538-1599) who lived in Lahore in the 16th century. It takes place at the shrine of Shah Hussain in Baghbanpura, on the outskirts of Lahore, Pakistan, adjacent to the Shalimar Gardens.[194]

Rath Yatra Nabha

Rath Yatra Nabha, Ratha Jatra or Chariot Festival is a Hindu festival associated with the god Jagannath held at Mandir Thakur Shri Saty Narayan Ji in the Nabha City, state of Punjab, India. This annual festival is celebrated in the month of August or September. The festival is connected to Jagannath's visit to Nabha city.[195]

See also

Notes

- Hindus of eastern and northeastern states of India associate the festival with the goddess Durga, or her fierce avatar Kali (Shaktism).[85] According to McDermott, this region also celebrated the Lakshmi puja historically, while the Kali puja tradition started in the colonial era and was particular prominent post-1920s.[86]

- Security concerns are another reason for the lack of holding fairs which lead to the Baisakhi mela in Gujranwala to mark wheat harvesting being cancelled in 2015.[143] Despite the bomb blast at the Sakhi Sarwar sufi shrine in Dera Ghazi Khan in 2011,[144] the Baisakhi mela around the water channel near the shrine that continues until the wheat harvest was integrated with the annual Urs of the saint in 2012.[145]

References

- Wade Davis; K. David Harrison; Catherine Herbert Howell (2007). Book of Peoples of the World: A Guide to Cultures. National Geographic. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4262-0238-4.

- Official Holidays 2016, Government of Punjab – Pakistan (2016)

- Official Holidays 2016 Archived 2018-09-01 at the Wayback Machine, Karachi Metropolitan, Sindh, Pakistan

- Census of India, 1961: Punjab. Manage of Publications

- Official Holidays, Government of Punjab, India (2016)

- Jacqueline Suthren Hirst; John Zavos (2013). Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia. Routledge. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-136-62668-5.;

Eid ul-Fitar, Ramzan Id/Eid-ul-Fitar in India, Festival Dates - Tej Bhatia (2013). Punjabi. Routledge. pp. 209–212. ISBN 978-1-136-89460-2.

- The ban on fun, IRFAN HUSAIN, Dawn, Feb 18, 2017

- The barricaded Muslim mind, Saba Naqvi (August 28, 2016), Quote: "Earlier, Muslim villagers would participate in 🕉️ festivals; now they think that would be haraam, so stay away. Visiting dargahs is also haraam"

- Jain, Harish (2003) Punjab Hand Book: Population and Housing Census. Unistar Books.

- POPULATION BY RELIGION, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

- D. C. Ahir (1992) Dr. Ambedkar and Punjab. B.R. Publishing Corporation

- Sarfraz, Emanuel The Nation (25.12.2016) Understanding the changing face of Christmas .

- Hindustan Times (25.12.2015) Christmas celebrations held across Punjab, Haryana and Chandigarh

- The Tribune (10/04/2017)

- Singh, Jangveer (10.09.2000) The Tribune: Tipri rhythms are fading out in region accessed 04.10.2019)

- Setiajatnika, Eka; Iriani, Kandis (2018-10-29). "Pengaruh Return on Asset, Asset Growth, dan Debt to Equity Ratio terhadap Dividend Payout Ratio". Jurnal Soshum Insentif: 22–34. doi:10.36787/jsi.v1i1.31. ISSN 2655-2698.

- McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563846-2 Quote: m Hindi rakśābandhan held on the full moon of the month of Savan, when sisters tie a talisman (rakhi q.v.) on the arm of their brothers and receive small gifts of money from them.

- Agarwal, Bina (1994), A Field of One's Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 264, ISBN 978-0-521-42926-9

- Berreman, Gerald Duane (1963), Hindus of the Himalayas, University of California Press, pp. 390–, GGKEY:S0ZWW3DRS4S Quote: Rakri: On this date Brahmins go from house to house tying string bracelets (rakrī) on the wrists of household members. In return the Brahmins receive from an anna to a rupee from each household. ... This is supposed to be auspicious for the recipient. ... It has no connotation of brother-sister devotion as it does in some plains areas. It is readily identified with Raksha Bandhan.

- Gnanambal, K. (1969), Festivals of India, Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, p. 10 Quote: In North India, the festival is popularly called Raksha Bandhan ... On this day, sisters tie an amulet round the right wrists of brothers wishing them long life and prosperity. Family priests (Brahmans) make it an occasion to visit their clientiele to get presents.

- Marriott, McKim (1955), "Little Communities in an Indigenous Civilization", in McKim Marriott (ed.), Village India: Studies in the Little Community, University of Chicago Press, pp. 198–202, ISBN 9780226506432

- Wadley, Susan S. (27 July 1994), Struggling with Destiny in Karimpur, 1925–1984, University of California Press, pp. 84, 202, ISBN 978-0-520-91433-9 Quote: (p 84) Potters: ... But because the festival of Saluno takes place during the monsoon when they can't make pots, they make pots in three batches ...

- Lewis, Oscar (1965), Village Life in Northern India: Studies in a Delhi Village, University of Illinois Press, p. 208, ISBN 9780598001207

- Coleman, Leo (2017), A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi, Cornell University Press, p. 127, ISBN 978-1-5017-0791-9 Quote: Rakhi and its local performances in Kishan Garhi were part of a festival in which connections between out-marrying sisters and village-resident brothers were affirmed. In the "traditional" form of this rite, according to Marriott, sisters exchanged with their brothers to ensure their ability to have recourse—at a crisis, or during childbearing—to their natal village and their relatives there even after leaving for their husband's home. For their part, brothers engaging in these exchanges affirmed the otherwise hard-to-discern moral solidarity of the natal family, even after their sister's marriage.

- Goody, Jack (1990), The Oriental, the Ancient and the Primitive: Systems of Marriage and the Family in the Pre-Industrial Societies of Eurasia, Cambridge University Press, p. 222, ISBN 978-0-521-36761-5 Quote: "... the heavy emphasis placed on the continuing nature of brother-sister relations despite the fact that in the North marriage requires them to live in different villages. That relation is celebrated and epitomised in the annual ceremony of Rakśābandhan in northern and western India. ... The ceremony itself involves the visit of women to their brothers (that is, to the homes of their own fathers, their natal homes)

- Hess, Linda (2015), Bodies of Song: Kabir Oral Traditions and Performative Worlds in North India, Oxford University Press, p. 61, ISBN 978-0-19-937416-8 Quote: "In August comes Raksha Bandhan, the festival celebrating the bonds between brothers and sisters. Married sisters return, if they can, to their natal villages to be with their brothers.

- Wadley, Susan Snow (2005), Essays on North Indian Folk Traditions, Orient Blackswan, p. 66, ISBN 978-81-8028-016-0 Quote: In Savan, greenness abounds as the newly planted crops take root in the wet soil. It is a month of joy and gaiety, with swings hanging from tall trees. Girls and women swing high into the sky, singing their joy. The gaiety is all the more marked because women, especially the young ones, are expected to return to their natal homes for an annual visit during Savan.

- Gnanambal, K. (1969), Festivals of India, Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, p. 10

- Coleman, Leo (2017), A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi, Cornell University Press, p. 148, ISBN 978-1-5017-0791-9 Quote: In modern rakhi, technologically mediated and performed with manufactured charms, migrating men are the medium by which the village women interact, vertically, with the cosmopolitan center—the site of radio broadcasts, and the source of technological goods and national solidarity

- Pandit, Vaijayanti (2003), Business @ Home, Vikas Publishing House, p. 234, ISBN 978-81-259-1218-7 Quote: "Quote: Raksha Bandhan traditionally celebrated in North India has acquired greater importance due to Hindi films. Lightweight and decorative rakhis, which are easy to post, are needed in large quantities by the market to cater to brothers and sisters living in different parts of the country or abroad."

- Khandekar, Renuka N. (2003), Faith: filling the God-sized hole, Penguin Books, p. 180, ISBN 9780143028840 Quote: "But since independence and the gradual opening up of Indian society, Raksha Bandhan as celebrated in North India has won the affection of many South Indian families. For this festival has the peculiar charm of renewing sibling bonds."

- Joshy, P. M.; Seethi, K. M. (2015), State and Civil Society under Siege: Hindutva, Security and Militarism in India, Sage Publications, p. 112, ISBN 978-93-5150-383-5 Quote: (p. 111) The RSS employs a cultural strategy to mobilise people through festivals. It observes six major festivals in a year. ... Till 20 years back, festivals like Raksha Bandhan were unknown to South Indians. Through Shakha's intense campaign, now they have become popular in the southern India. In colleges and schools tying `Rakhi'—the thread that is used in the 'Raksha Bandhan'—has become a fashion and this has been popularised by the RSS and ABVP cadres.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (1999), The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s : Strategies of Identity-building, Implantation and Mobilisation (with Special Reference to Central India), Penguin Books, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-14-024602-5 Quote: This ceremony occurs in a cycle of six annual festivals which often coincides with those observed in Hindu society, and which Hedgewar inscribed in the ritual calendar of his movement: Varsha Pratipada (the Hindu new year), Shivajirajyarohonastava (the coronation of Shivaji), guru dakshina, Raksha Bandhan (a North Indian festival in which sisters tie ribbons round the wrists of their brothers to remind them of their duty as protectors, a ritual which the RSS has re-interpreted in such a way that the leader of the shakha ties a ribbon around the pole of the saffron flag, after which swayamsevaks carry out this ritual for one another as a mark of brotherhood), ....

- Coleman, Leo (2017), A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi, Cornell University Press, p. 148, ISBN 978-1-5017-0791-9 Quote: ... as citizens become participants in the wider "new traditions" of the national state. Broadcast mantras become the emblems of a new level of state power and the means of the integration of villagers and city dwellers alike into a new community of citizens

- Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert L. (1996), India: A Country Study, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, p. 246, ISBN 978-0-8444-0833-0

- Vanita, Ruth (2002), "Dosti and Tamanna: Male-Male Love, Difference, and Normativity in Hindi Cinema", in Diane P. Mines; Sarah Lamb (eds.), Everyday Life in South Asia, Indiana University Press, pp. 146–158, 157, ISBN 978-0-253-34080-1

- Chowdhry, Prem (1994), The Veiled Women: Shifting Gender Equations in Rural Haryana, Oxford University Press, pp. 312–313, ISBN 978-0-19-567038-7 Quote: The same symbolic protection is also requested from the high caste men by the low caste women in a work relationship situation. The ritual thread is offered, though not tied and higher caste men customarily give some money in return.

- Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 314–315

- J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 396. ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0.

- Edwin Francis Bryant (2007). Sri Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 224–225, 538–539. ISBN 978-0-19-803400-1.

- "In Pictures: People Celebrating Janmashtami in India". International Business Times. 10 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Cynthia Packert (2010). The Art of Loving Krishna: Ornamentation and Devotion. Indiana University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-253-00462-8.

- "Mahashivaratri Festival : Festival of Shivratri, Mahashivratri Festival India – Mahashivaratri Festival 2019". Mahashivratri.org. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- McKim Marriott (2006). John Stratton Hawley and Vasudha Narayanan (ed.). The Life of Hinduism. University of California Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-520-24914-1.

- The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) ISBN 0-19-861263-X - p.874 "Holi /'həʊli:/ noun a Hindu spring festival ..."

- Monier-Williams, Sir Monier (1876). Indian Wisdom Or Exemples of the Religions, Philosophical, and Ethical Doctrines of the Hindus: with a Brief History of the Chief Departments of Sanskrit Literature. 3. Ed. Allen.

- Rait, S.K (2005) Sikh Women in England: Their Religious and Cultural Beliefs and Social Practices. Trentham Books.

- Parminder Singh Grover and Moga, Davinderjit Singh, Discover Punjab: Attractions of Punjab

- Jasbir Singh Khurana, Punjabiyat: The Cultural Heritage and Ethos of the People of Punjab, Hemkunt Publishers (P) Ltd, ISBN 978-81-7010-395-0

- Drawing Designs on Walls, Trisha Bhattacharya (13 October 2013), Deccan Herald. Retrieved 7 January 2015

- Dabas, Maninder (28 Sep 2017). "Here's The Story Of Sanjhi - A Forgotten Festival And Delhi's 'Own Version' Of Durga Puja". India Times. Archived from the original on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 30 Sep 2018.

- "Sanjhi". Haryana Online. Archived from the original on 28 June 2002. Retrieved 30 Sep 2018.

- "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - Punjab".

- General, India Office of the Registrar (1962). Census of India, 1961: Punjab. Manager of Publications.

- J. Gordon Melton; Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 1769. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- Diana L. Eck (2013). India: A Sacred Geography. Random House. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0-385-53192-4.

- General, India Office of the Registrar (1962). Census of India, 1961: Punjab. Manager of Publications.

- Rinehart, Robin; Rinehart, Robert (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- Kelly, Aidan A.; Dresser, Peter D.; Ross, Linda M. (1993). Religious Holidays and Calendars: An Encyclopaedic Handbook. Omnigraphics, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-55888-348-2.

- Harjinder Singh. Vaisakhi. Akaal Publishers. p. 2.

- K.R. Gupta; Amita Gupta (2006). Concise Encyclopaedia of India. Atlantic Publishers. p. 998. ISBN 978-81-269-0639-0.

- Christian Roy (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 479–480. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- A Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province. Low Price Publications. 1999. ISBN 978-81-7536-153-9.

- Nijjar, Bakhshish Singh (1972). Panjab Under the Later Mughals, 1707-1759. New Academic Publishing Company.

- Gazetteer of the Ferozpur District: 1883. 1883.

- Khalid, Haroon (28 April 2017). "In defiance: Celebrating Baisakhi at a Hindu shrine in Pakistan". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Darshan. Consulate-General of India. 1982.

- Punjab (India) (1992). Punjab District Gazetteers: Supplement. Controller of Print. and Stationery.

- Anand, R.L. (1962). Fairs and Festivals, Part VII-B, Vol-XIII, Punjab, Census of India 1961. p. 60.

- "Rama Navami – Hindupedia, the Hindu Encyclopedia". Hindupedia.com. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- Encyclopedia Britannica Dussehra 2015.

- Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 212–213.

- Ramlila, the traditional performance of the Ramayana, UNESCO

- Jones & Ryan 2006, pp. 308–309.

- John William Kaye; William Simpson (1867). India ancient and modern: a series of illustrations of the Country and people of India and adjacent territories. Executed in chromolithography from drawings by William Simpson. London Day and Son. p. 50. OCLC 162249047.

- The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) ISBN 978-0-19-861263-6 – p. 540 "Diwali /dɪwɑːli/ (also Diwali) noun a Hindu festival with lights...".

- Diwali Encyclopædia Britannica (2009)

- "Diwali 2020 Date in India: When is Diwali in 2020?". The Indian Express. 11 November 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- Vasudha Narayanan; Deborah Heiligman (2008). Celebrate Diwali. National Geographic Society. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4263-0291-6.

All the stories associated with Deepavali, however, speak of the joy connected with the victory of light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, and good over evil.

- Tina K Ramnarine (2013). Musical Performance in the Diaspora. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-317-96956-3.

Light, in the form of candles and lamps, is a crucial part of Diwali, representing the triumph of light over darkness, goodness over evil and hope for the future.

- Jean Mead, How and why Do Hindus Celebrate Divali?, ISBN 978-0-237-53412-7

- J Gordon Melton 2011, p. 252.

- Pramodkumar (2008). Meri Khoj Ek Bharat Ki. ISBN 978-1-4357-1240-9. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

It is extremely important to keep the house spotlessly clean and pure on Diwali. The goddess Lakshmi likes cleanliness, and she will visit the cleanest house first. Lamps are lit in the evening to welcome the goddess. They are believed to light up her path.

- Laura Amazzone 2012.

- McDermott 2011, pp. 183–188.

- India Journal: ‘Tis the Season to be Shopping Devita Saraf, The Wall Street Journal (August 2010)

- Henry Johnson 2007, pp. 71–73.

- Kelly 1988, pp. 40–55.

- Karen Bellenir (1997). Religious Holidays and Calendars: An Encyclopedic Handbook, 2nd Edition, ISBN 978-0-7808-0258-2, Omnigraphics

- Rajat Gupta; Nishant Singh; Ishita Kirar. Hospitality & Tourism Management. Vikas. p. 84. ISBN 978-93-259-8244-4.

- Kristen Haar; Sewa Singh Kalsi (2009). Sikhism. Infobase Publishing. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-1-4381-0647-2.

- Shobhna Gupta (2002). Festivals of India. Har-Anand. p. 84. ISBN 978-81-241-0869-7.

- Alop ho riha Punjabi Visra by Harkesh Singh Kehal Unistar Publications PVT Ltd ISBN 81-7142-869-X

- Madhusree Dutta, Neera Adarkar, Majlis Organization (Bombay) (1996), The nation, the state, and Indian identity, Popular Prakashan, 1996, ISBN 978-81-85604-09-1,

... originally was practised by women in Punjab and parts of UP, is gaining tremendous popularity ... We found women of all classes and regional communities ... all said they too were observing the Karva Chauth Vrat for their husbands' longevity. All of them had dekha-dekhi (in imitation) followed a trend which made them feel special on this one day. Husbands paid them undivided attention and showered them with gifts. The women from the bastis go to beauty parlours to have their hair set and hands decorated with mehendi

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pritam, Amrita. Dekhya Kabira (1996)

- Alop ho riha Punjabi Visra by Harkesh Singh Kehal Bhag Dooja Unistar Publications PVT Ltd ISBN 978-93-5017-532-3

- Khoja darapaṇa, Volume 22, Issue 1 1999

- "Sikh History". Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- "Happy Guru Gobind Singh Jayanti: Wishes, Pics, Facebook Messages To Share". NDTV.com. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Vanjara Bedi, S. S. "SODHI". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Patiala. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "BBC Religions - Sikhism". BBC. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I.B.Tauris. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-85773-549-2.

- Dilagīra, Harajindara Siṅgha (1997). The Sikh Reference Book. Sikh Educational Trust for Sikh University Centre, Denmark. ISBN 978-0-9695964-2-4.

- Singh, Sardar Harjeet (2009). Faith & Philosophy of Sikhism. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7835-721-8.

- Jeratha, Aśoka (1998). Dogra Legends of Art & Culture. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-082-8.

- Śarmā, Baṃśī Rāma (2007). Gods of Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7387-209-9.

- Chauhan, Ramesh K. (1995) Punjab and the nationality question in India. Deep and Deep Publications

- McLeod, W. H. (2009) The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press

- "The Tribune...Science Tribune". Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- The Tribune Festival binge: Amarjot Kaur 10 January 2015

- Celebrating with the Robin Hood of the Punjab and all his friends! Nottingham Post 13 01 2014 "Celebrating with the Robin Hood of the Punjab and all his friends! | Nottingham Post". Archived from the original on 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- Dr. H.S. Singha (2005). Sikh Studies. Hemkunt Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-81-7010-245-8.

- Punjab notifies gazetted, restricted holidays for 2016, The Hindustan Times (2016)

- Public and Optional Holidays, Government of Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan (2017)

- Asian News Jan 2013: Lohri celebrated in Faisalabad, Punjab, Pakistan

- Sundar mundarye ho by Assa Singh Ghuman Waris Shah Foundation ISBN B1-7856-043-7

- General, India Office of the Registrar (1962). Census of India, 1961: Punjab. Manager of Publications.

- Gupta, Shakti M. (1991). Festivals, Fairs, and Fasts of India. Clarion Books. ISBN 978-81-85120-23-2.

- 'Rauh di kheer’ is the people's favourite. (14.01.2017 )The Tribune. accessed 15.01.2017

- Sekhon, Iqbal S. The Punjabis. 2. Religion, society and culture of the Punjabis. Cosmos (2000)

- Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 741–742

- J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 903. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7., Quote: "Vasant Panchami is a day to think about the person one loves, a spouse or special friend. In rural areas, people note that the crops are already in the field and rippening. It has in the modern world developed a reputation as a Hindu form of Valentine's Day."

- ASPECTS OF PUNJABI CULTURE S. S. NARULA Published by PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, INDIA, 1991

- Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I.B.Tauris. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-85773-549-2.

- The Sikh World: An Encyclopedia Survey of Sikh Religion and Culture: Ramesh Chander Dogra and Urmila Dogra; ISBN 81-7476-443-7

- Punjabiat: The Cultural Heritage and Ethos of the People of Punjab: Jasbir Singh Khurana

- PT (07.02.2017) Punjab govt says ‘NO’ to Basant festival

- Pakistan's Punjab govt imposes ‘complete ban’ on Basant festival, The Hindustan Times (Apr 03, 2017)

- Cath Senker (2007). My Sikh Year. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4042-3733-9., Quote: "Vaisakhi is the most important mela. It marks the Sikh New Year. At Vaisakhi, Sikhs remember how their community, the Khalsa, first began."

- Knut A. Jacobsen (2008). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4., Quote: "Baisakhi is also a Hindu festival, but for the Sikhs, it celebrates the foundation of the Khalsa in 1699."

- Bakshi, S. R. Sharma, Sita Ram (1998) Parkash Singh Badal: Chief Minister of Punjab

- Gupta, Surendra K. (1999) Indians in Thailand, Books India International

- Dogra, Ramesh Chander and Dogra, Urmila (2003) Page 49 The Sikh World: An Encyclopedic Survey of Sikh Religion and Culture. UBS Publishers Distributors Pvt Ltd ISBN 81-7476-443-7

- Sainik Samachar: The Pictorial Weekly of the Armed Forces, Volume 33 (1986) Director of Public Relations, Ministry of Defence,

- Dhillon, (2015) Janamsakhis: Ageless Stories, Timeless Values. Hay House

- "Link: Indian Newsmagazine". 13 April 1987 – via Google Books.

- Nahar, Emanual (2007) Minority politics in India: role and impact of Christians in Punjab politics. Arun Pub. House.

- Cultural Decline in Pakistan, Pakistan Today, Aziz-ud-din Ahmed (February 21, 2015)

- Pakistan Today (8 April 2016) Punjabi Parchar spreads colours of love at Visakhi Mela

- A fair dedicated to animal lovers (20.04.2009) Dawn

- Agnes Ziegler, Akhtar Mummunka (2006) The final Frontier: unique photographs of Pakistan. Sang-e-Meel Publications

- Dunya New 14 April 2016: Gujranwala: Baisakhi festival cancelled due to security threats

- BBC News (03 04 2011) Pakistan Sufi shrine suicide attack kills 41

- Tariq Ismaeel (01.03. 2012)"Sakhi Sarwar: Thousands arrive for festival ahead of urs" The Express Tribune

- Dr Singh, Sadhu (2010) Punjabi Boli Di Virasat. Chetna Prakashan. ISBN 817883618-1

- "Baisakhi celebrated with fervour, gaiety in J&K". 14 April 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Punia, Bijender K. (1 January 1994). Tourism Management: Problems and Prospects. APH Publishing. ISBN 9788170246435. Retrieved 14 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- Alop Ho Raha Punjabi Virsa: Harkesh Singh KehalUnistar Books PVT Ltd ISBN 81-7142-869-X

- Shankarlal C. Bhatt (2006) Land and People of Indian States and Union Territories: In 36 Volumes. Punjab, Volume 22

- Rainuka Dagar (2002) Identifying and Controlling Female Foeticide and Infanticide in Punjab

- J Mohapatra (December 2013). Wellness In Indian Festivals & Rituals. Partridge. p. 125. ISBN 9781482816907.

- Manju Bhatnagar (1988). "The Monsoon Festival Teej in Rajasthan". Asian Folklore Studies. 47 (1): 63–72. doi:10.2307/1178252. JSTOR 1178252.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016) Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press

- Marian de Souza, Gloria Durka, Kathleen Engebretson, Robert Jackson, Andrew McGrad (2007) International Handbook of the Religious, Moral and Spiritual Dimensions in Education. Springer

- People of India: A - G., Volume 4 (1998) Oxford Univ. Press

- "Raksha bandhan is here!". The Hindu. 2014-08-08. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- Fedorak, Shirley (2006) Windows on the World: Case Studies in Anthropology. Nelson.

- Hess, Linda (2015) Bodies of Song: Kabir Oral Traditions and Performative Worlds in North India. Oxford University Press

- "Articles - Siblings Day Foundation". Archived from the original on 2016-06-17. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- Kristen Haar, Sewa Singh Kalsi (2009) Sikhism

- Pande, Alka (1999) Folk Music & Musical Instruments of Punjab: From Mustard Fields to Disco Lights, Volume 1

- Alop ho riha Punjabi virsa - bhag dooja by Harkesh Singh Kehal Unistar Book PVT Ltd ISBN 978-93-5017-532-3

- Mohiuddin, Yasmeen Niaz (2007) Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO

- Leaman,Oliver (2006 The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis

- The Express Tribune (05.09.2015) Eid preparations: Eight Eid cattle markets to be set up in Multan

- Sharma, Arjun (14.09.2015)Goat sellers go online ahead of Bakr-Eid, to affect direct retail The Hindustan Times

- 1998 provincial census report of Punjab (2001) Population Census Organization

- Barbara DuMoulin, Sylvia Sikundar (1998) Celebrating Our Cultures: Language Arts Activities for Classroom Teachers. Pembroke Publishers Limited

- Bhalla,Kartar Singh 2005) Let's Know Festivals of India. Star Publications

- Kamal, Neel (01.09.2011) The Times of India. Eid celebrated with fervour in Malerkotla

- Guide to Lahore. Ferozsons

- Edelstein, Sari (2011) Food, Cuisine, and Cultural Competency for Culinary, Hospitality, and Nutrition Professionals. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- The Nation. (25.01.2013) City celebrates Eid Miladun Nabi

- Nestorović, Čedomir (2016) Islamic Marketing: Understanding the Socio-Economic, Cultural, and Politico-Legal Environment. Springer

- Paracha, Nadeem. F. Dawn (02.02.2017) Pakistan: The lesser-known histories of an ancient land

- The Express Tribune (16.02.2011) Eid-e-Milad-un-Nabi celebrations: What's new on the milad menu?

- Khalid, Haroon (14.02.2011) Celebrating Eid Millad ul Nabi by Haroon Khalid. Lahorenama

- The Tribune (25.12.2015) Milad-un-Nabi celebrated

- Jean, Calmard (2011). "AZĀDĀRĪ". iranicaonline.

- Martín, Richard C. (2004). Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim World. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 488.

- Jacobsen, Knut A. (ed) (2008) South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1982) Islam in India and Pakistan. BRILL

- (26.10.2015) The Nation Punjab marks Ashura with fervour amid tight security.

- Knut A. Jacobsen (2008) South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge.

- Reza Masoudi Nejad (2015). Peter van der Veer (ed.). Handbook of Religion and the Asian City: Aspiration and Urbanization in the Twenty-First Century. University of California Press. pp. 89–105. ISBN 978-0-520-96108-1.

- Proceedings, Volume 21 (1988) Punjab History Conference. Punjab University.

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892) Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities: With an Account of its Modern Institutions, Inhabitants, Their, Customs. New Imperial Press.

- The Express Tribune (12.10.2016) Annual commemoration: Mourners brace for Ashura amid tight security.

- Randhawa, Karenjot Bhangoo (2012) Civil Society in Malerkotla, Punjab: Fostering Resilience through Religio. Lexington Books

- The Tribune (13.10.2016 ) Muharram observed amid tight security

- The International News (12.10.2016) Security tightened in City on Youm-e-Ashur

- Torab, Azam (2007) Performing Islam: Gender and Ritual in Islam. BRILL

- http://apnaorg.com/articles/news-1/, An article on Mela Chiraghan on Academy of the Punjab in North America (APNA) website, Published 29 March 2005, Retrieved 19 Aug 2016

- Singha, H.s (2000) The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press.

Sources cited

- Laura Amazzone (2012). Goddess Durga and Sacred Female Power. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-5314-5.

- Henry Johnson (2007). "'Happy Diwali!' Performance, Multicultural Soundscapes and Intervention in Aotearoa/New Zealand". Ethnomusicology Forum. 16 (1): 71–94. doi:10.1080/17411910701276526. JSTOR 20184577. S2CID 191322269.

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- Kelly, John D. (1988). "From Holi to Diwali in Fiji: An Essay on Ritual and History". Man. 23 (1): 40–55. doi:10.2307/2803032. JSTOR 2803032.

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A–M. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0823931798.

- McDermott, Rachel Fell (2011). Revelry, Rivalry, and Longing for the Goddesses of Bengal. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52787-3.

- J Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays Festivals Solemn Observances and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0.

- "Dussehra – Hindu festival". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2017.