Zinc pyrithione

| |

Zinc pyrithione dimer | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

bis(2-pyridylthio)zinc 1,1'-dioxide | |

| Other names

ZnP, Pyrithione Zinc, Zinc OMADINE, ZnPT | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.324 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H8N2O2S2Zn | |

| Molar mass | 317.70 g/mol |

| Appearance | colourless solid |

| Melting point | 240 °C (464 °F; 513 K) (decomposition)[1] |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| 8 ppm (pH 7) | |

| Pharmacology | |

| D11AX12 (WHO) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Zinc pyrithione (or pyrithione zinc) is a coordination complex of zinc. It has fungistatic (inhibiting the division of fungal cells) and bacteriostatic (inhibiting bacterial cell division) properties and is used in the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis[2] and dandruff.

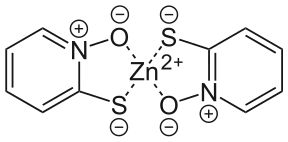

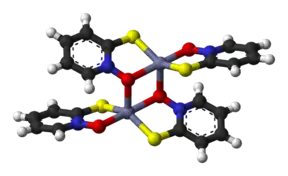

Structure of the compound

The pyrithione ligands, which are formally monoanions, are chelated to Zn2+ via oxygen and sulfur centers. In the crystalline state, zinc pyrithione exists as a centrosymmetric dimer (see figure), where each zinc is bonded to two sulfur and three oxygen centers.[3] In solution, however, the dimers dissociate via scission of one Zn-O bond.

This compound was first described in the 1930s.[4]

Pyrithione is the conjugate base derived from 2-mercaptopyridine-N-oxide (CAS# 1121-31-9), a derivative of pyridine-N-oxide.

Uses

Medicine

Zinc pyrithione can be used to treat dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis.[5][6][7] It also has antibacterial properties and is effective against many pathogens from the Streptococcus and Staphylococcus genera.[8] Its other medical applications include treatments of psoriasis, eczema, ringworm, fungus, athletes foot, dry skin, atopic dermatitis, tinea versicolor,[9][8] and vitiligo.

Paint

Because of its low solubility in water (8 ppm at neutral pH), zinc pyrithione is suitable for use in outdoor paints and other products that protect against mildew and algae. It is an algaecide. It is chemically incompatible with paints relying on metal carboxylate curing agents. When it is used in latex paints with water containing much iron, a sequestering agent that preferentially binds the iron ions is needed. It is decomposed by ultraviolet light slowly, providing years of protection in direct sunlight.

Sponges

Zinc pyrithione is an antibacterial treatment for household sponges, as used by the 3M Corporation.[10]

Clothing

A process to apply zinc pyrithione to cotton with washable results was patented in the United States in 1984.[11] Zinc pyrithione is used to prevent microbe growth in polyester.[12] Textiles with applied zinc pyrithione protect against odor-causing microorganisms. Export of antimicrobial textiles reached US$497.4 million in 2015.[13]

Mechanism of action

Its antifungal effect is thought to derive from its ability to disrupt membrane transport by blocking the proton pump that energizes the transport mechanism.[14]

Health effects

Zinc pyrithione is approved for over-the-counter topical use in the United States as a treatment for dandruff and is the active ingredient in several anti-dandruff shampoos and body wash gels. In its industrial forms and strengths, it may be harmful by contact or ingestion. Zinc pyrithione can in the laboratory setting trigger a variety of responses, such as DNA damage in skin cells.[15]

Legal status

Use of zinc pyrithione is prohibited in the European Union since December 2021.[16] The substance was considered safe for use in rinse-off and leave-in products of different tested concentrations, but due to environmental toxicity standard regulation was considered against potential alternatives – and as no submission was made for its use it was automatically prohibited.[16]

Environmental concerns

A large Swedish study shows that it is broken down in wastewater plants and does not release into waterways.[17] A Danish study shows that it biodegrades quickly, but that a risk of continuous leaching from boat paint may cause environmental toxicity.[18]

See also

- Ketoconazole, another antifungal agent used in shampoos

- Piroctone olamine, another antifungal agent used in shampoos

- Selenium disulfide, an active ingredient used in shampoos such as Selsun Blue

References

- Entry on Zink-Pyrithion. at: Römpp Online. Georg Thieme Verlag, retrieved 5 November 2020.

- Brayfield, A, ed. (23 September 2011). "Pyrithione Zinc". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Barnett, B. L.; Kretschmar, H. C.; Hartman, F. A. (1977). "Structural characterization of bis(N-oxopyridine-2-thionato)zinc(II)". Inorg. Chem. 16 (8): 1834–8. doi:10.1021/ic50174a002.

- prof. Mark Draganjac. "Pyrithione zinc". www.cas.astate.edu. Arkansas State University. Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- Marks, R.; Pearse, A. D.; Walker, A. P. (April 1985). "The effects of a shampoo containing zinc pyrithione on the control of dandruff". The British Journal of Dermatology. 112 (4): 415–422. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02314.x. ISSN 0007-0963. PMID 3158327. S2CID 23368244.

- Piérard-Franchimont, Claudine; Goffin, Véronique; Decroix, Jacques; Piérard, Gérald E. (November 2002). "A multicenter randomized trial of ketoconazole 2% and zinc pyrithione 1% shampoos in severe dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis". Skin Pharmacology and Applied Skin Physiology. 15 (6): 434–441. doi:10.1159/000066452. ISSN 1422-2868. PMID 12476017. S2CID 23162407.

- Ive, F. A. (1991). "An overview of experience with ketoconazole shampoo". The British Journal of Clinical Practice. 45 (4): 279–284. ISSN 0007-0947. PMID 1839767.

- "Zinc pyrithione". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- Faergemann, J. (2000). "Management of Seborrheic Dermatitis and Pityriasis Versicolor". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 1 (2): 75–80. doi:10.2165/00128071-200001020-00001. ISSN 1175-0561. PMID 11702314. S2CID 43516330.

- Notice of Filing a Pesticide Petition to Establish

- US US4443222A, Morris; Cletus E. & Welch; Clark M., issued 17 April 1984, assigned to The United States of America as represented by the Secretary of Agriculture

- "Zptech, Zinc Odor Control for Textiles". microban.com. Microban International. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- Jain, Anil Kumar; Tesema, Addisu Ferede. "Development of antimicrobial textiles using zinc pyrithione". ResearchGate. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Chandler CJ, Segel IH (1978). "Mechanism of the Antimicrobial Action of Pyrithione: Effects on Membrane Transport, ATP Levels, and Protein Synthesis". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 14 (1): 60–8. doi:10.1128/aac.14.1.60. PMC 352405. PMID 28693.

- Leading references: Lamore SD, Cabello CM, Wondrak GT (May 2010). "The topical antimicrobial zinc pyrithione is a heat shock response inducer that causes DNA damage and PARP-dependent energy crisis in cultured human skin cells". Cell Stress & Chaperones. 15 (3): 309–22. doi:10.1007/s12192-009-0145-6. PMC 2866994. PMID 19809895.

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2021/1902 of 29 October 2021 amending Annexes II, III and V to Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the use in cosmetic products of certain substances classified as carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction (Text with EEA relevance), 3 November 2021, retrieved 9 August 2022

- "Results from the Swedish Screening Programme 2006 Subreport 3: Zinc pyrithione and Irgarol 1051" (PDF). ivl.se. Swedish Environmental Research Institute . September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- "Ecotoxocicological assessment of antifouling biocides and non-biocidal antifouling paints". Miljøstyrelsen - Miljøministeriet. Ministry of Environment (Denmark). Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

External links

- "Pyrithione zinc". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.