History of the Quakers

The Religious Society of Friends began as a proto-evangelical Christian movement in England in the mid-17th century in Lancashire.[1][2] Members are informally known as Quakers, as they were said "to tremble in the way of the Lord". The movement in its early days faced strong opposition and persecution, but it continued to expand across the British Isles and then in the Americas and Africa.

| Part of a series on |

| Quakerism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Quakers, though few in numbers, have been influential in the history of reform. The colony of Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn in 1682, as a safe place for Quakers to live and practice their faith. Quakers have been a significant part of the movements for the abolition of slavery, to promote equal rights for women, and peace. They have also promoted education and the humane treatment of prisoners and the mentally ill, through the founding or reforming of various institutions. Quaker entrepreneurs played a central role in forging the Industrial Revolution, especially in England and Pennsylvania.

During the 19th century, Friends in the United States suffered a number of secessions, which resulted in the formation of different branches of the Religious Society of Friends.

The Quakers have historically believed in equality for men and women. Two Quaker women are part of the history of science, specifically astronomy. Jocelyn Bell Burnell, from Northern Ireland, is credited with being a key part of research that later led to a Nobel Prize Physics. However, she was not a recipient of the prize.[3] Maria Mitchell (1818-1889) was the first internationally known woman to work as both a professional astronomer and a professor of astronomy.[4]

George Fox and the Religious Society of Friends

When George Fox was eleven, he wrote that God spoke to him about "keeping pure and being faithful to God and man."[2] After being troubled when his friends asked him to drink alcohol with them at the age of nineteen, Fox spent the night in prayer and soon afterwards, he left his home to search for spiritual satisfaction, which lasted four years.[2] In his Journal, at age 23, he recorded the words:[2]

And when all my hopes in them and in all men were gone, so that I had nothing outwardly, to help me, nor could tell what to do; then, O then, I heard a voice which said 'There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can speak to thy condition.' When I heard it, my heart did leap for joy. Then the Lord let me see why there was none upon the earth that could speak to my condition, namely, that I might give him all the glory. For all are concluded under sin, and shut up in unbelief, as I had been, that Jesus Christ might have the pre-eminence, who enlightens, and gives grace, faith, and power. Thus when God doth work, who shall let (hinder) it?[2]

At this time, Fox believed that he "found through faith in Jesus Christ the full assurance of salvation."[2] Fox began to spread his evangelical Christian message and his emphasis on "the necessity of an inward transformation of heart", as well as the possibility of Christian perfection, drew opposition from English clergy and laity.[2] Fox wrote that "The professors [professing Christians] were in a rage, all pleading for sin and imperfection, and could not endure to hear talk of perfection, or of a holy and sinless life."[2] However, in the mid-1600s, many people became attracted to Fox's preaching and his followers became known as Friends.[2] By 1660, the Quakers grew to 35,000.[2] Well known early advocates of Quaker Christianity included Isaac Penington, Robert Barclay, Thomas Ellwood, William Penn and Margaret Fell.[2]

Quakerism pulled together groups of disparate Seekers that formed the Religious Society of Friends following 1647. This time of upheaval and social and political unrest called all institutions into question, so George Fox and his leading disciples—James Nayler, Richard Hubberthorne, Margaret Fell, as well as numerous others—targeted "scattered Baptists", disillusioned soldiers, and restless common folk as potential Quakers. Confrontations with the established churches and its leaders and those who held power at the local level assured those who spoke for the new sect a ready hearing as they insisted that God could speak to average people, through his risen son, without the need to heed churchmen, pay tithes, or engage in deceitful practices. They found fertile ground in northern England in 1651 and 1652, building a base there from which they moved south, first to London and then beyond. In the early days the groups remained scattered, but gradually they consolidated in the north—the first meeting being created in Durham in 1653—to provide financial support to the missionaries who had gone south and presently abroad. Before long they seemed a potential threat to the dignity of the Cromwellian state. Even arresting its leaders failed to slow the movement, instead giving them a new audience in the courts of the nation.[5]

Nayler's sign

In 1656, a popular Quaker minister, James Nayler, went beyond the standard beliefs of Quakers when he rode into Bristol on a horse in the pouring rain, accompanied by a handful of men and women saying "Holy, holy, holy" and strewing their garments on the ground, imitating Jesus's entry into Jerusalem. While this was apparently an attempt to emphasize that the "Light of Christ" was in every person, most observers believed that he and his followers believed Nayler to be Jesus Christ. The participants were arrested by the authorities and handed over to Parliament, where they were tried. Parliament was sufficiently incensed by Nayler's heterodox views that they punished him savagely and sent him back to Bristol to jail indefinitely.[6] This was especially bad for the movement's respectability in the eyes of the Puritan rulers because some considered Nayler (and not Fox, who was in jail at the time) to be the actual leader of the movement. Many historians see this event as a turning point in early Quaker history because many other leaders, especially Fox, made efforts to increase the authority of the group, so as to prevent similar behaviour. This effort culminated in 1666 with the "Testimony from the Brethren", aimed at those who, in its own words, despised a rule "without which we ... cannot be kept holy and inviolable"; it continued the centralizing process that began with the Nayler affair and was aimed at isolating any separatists who still lurked in the Society. Fox also established women's meetings for discipline and gave them an important role in overseeing marriages, which served both to isolate the opposition and fuel discontent with the new departures. In the 1660s and 1670s Fox himself travelled the country setting up a more formal structure of monthly (local) and quarterly (regional) meetings, a structure that is still used today.[7]

Other early controversies

The Society was rent by controversy in the 1660s and 1670s because of these tendencies. First, John Perrot, previously a respected minister and missionary, raised questions about whether men should uncover their heads when another Friend prayed in meeting. He also opposed a fixed schedule for meetings for worship. Soon this minor question broadened into an attack on the power of those at the centre. Later, during the 1670s, William Rogers of Bristol and a group from Lancashire, whose spokesmen John Story and John Wilkinson were both respected leaders, led a schism. They disagreed with the heightening influence of women and centralizing authority among Friends closer to London. In 1666, a group of about a dozen leaders, led by Richard Farnworth (Fox was absent, being in prison in Scarborough), gathered in London and issued a document that they styled "A Testimony of the Brethren". It set rules to maintain the good order that they wanted to see among adherents and excluded separatists from holding office and prohibited them from travelling lest they sow errors. Looking to the future, they announced that authority in the Society rested with them.[8] By the end of the century, these leaders were almost all now dead but London's authority had been established; the influence of dissident groups had been mostly overcome.

Women and equality

One of their most radical innovations was a more nearly equal role for women, as Taylor (2001) shows. Despite the survival of strong patriarchal elements, Friends believed in the spiritual equality of women, who were allowed to take a far more active role than had ordinarily existed before the emergence of radical civil war sects. Among many female Quaker writers and preachers of the 1650s to 1670s were Margaret Fell, Dorothy White, Hester Biddle, Sarah Blackborow, Rebecca Travers and Alice Curwen.[9] Early Quaker defenses of their female members were sometimes equivocal, however, and after the Restoration of 1660 the Quakers became increasingly unwilling to publicly defend women when they adopted tactics such as disrupting services. Women's meetings were organized as a means to involve women in more modest, feminine pursuits. Writers such as Dorcas Dole and Elizabeth Stirredge turned to subjects seen as more feminine in that period.[10] Some Quaker men sought to exclude them from church public concerns with which they had some powers and responsibilities, such as allocating poor relief and in ensuring that Quaker marriages could not be attacked as immoral. The Quakers continued to meet openly, even in the dangerous year of 1683. Heavy fines were exacted and, as in earlier years, women were treated as severely as men by the authorities.[11]

Persecution in England

In 1650 George Fox was imprisoned for the first time. Over and over he was thrown in prison during the 1650s through the 1670s. Other Quakers followed him to prison as well. The charge was causing a disturbance; at other times it was blasphemy.[12]

Two acts of Parliament made it particularly difficult for Friends. The first was the Quaker Act of 1662[13] which made it illegal to refuse to take the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown. Those refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown were not allowed to hold any secret meetings and, because Friends believed it was wrong to take any "superstitious" oath, their freedom of religious expression was certainly compromised by this law. The second was the Conventicle Act of 1664 which reaffirmed that the holding of any secret meeting by those who did not pledge allegiance to the Crown was a crime. Despite these laws, Friends continued to meet openly.[14] They believed that by doing so, they were testifying to the strength of their convictions and were willing to risk punishment for doing what they believed to be right.

The ending of official persecution in England

Under James II of England, persecution practically ceased.[15] James issued a Declaration of Indulgence in 1687 and 1688, and it was widely held that William Penn had been its author.[16]

In 1689 the Toleration Act was passed. It allowed for freedom of conscience and prevented persecution by making it illegal to disturb anybody else from worship. Thus Quakers became tolerated though still not widely understood or accepted.

Netherlands

Quakers first arrived in the Netherlands in 1655 when William Ames and Margaret Fell's nephew, William Caton, took up residence in Amsterdam.[17] The Netherlands were seen by Quakers as a refuge from persecution in England and they perceived themselves to have affinities with the Dutch Collegiants and also with the Mennonites who had sought sanctuary there. However, English Quakers encountered persecution no different from that they had hoped to leave behind. Eventually, however, Dutch converts to Quakerism were made, and with Amsterdam as a base, preaching tours began within the Netherlands and to neighboring states. In 1661, Ames and Caton visited the County Palatine of the Rhine and met with Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine at Heidelberg.

William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania, who had a Dutch mother, visited the Netherlands in 1671 and saw, first hand, the persecution of the Emden Quakers.[18] He returned in 1677 with George Fox and Robert Barclay and at Walta Castle, their religious community at Wieuwerd in Friesland, he unsuccessfully tried to convert the similarly minded Labadists to Quakerism. They also journeyed on the Rhine to Frankfurt, accompanied by the Amsterdam Quaker Jan Claus who translated for them. His brother, Jacob Claus, had Quaker books translated and published in Dutch and he also produced a map of Philadelphia, the capital of Penn's Holy Experiment.

The attraction of a life free from persecution in the New World led to a gradual Dutch Quaker migration. English Quakers in Rotterdam were permitted to transport people and cargo by ship to English colonies without restriction and throughout the 18th century many Dutch Quakers emigrated to Pennsylvania.[18] There were an estimated 500 Quaker families in Amsterdam in 1710[19] but by 1797 there were only seven Quakers left in the city. Isabella Maria Gouda (1745–1832), a granddaughter of Jan Claus, took care of the meeting house on Keizersgracht but when she stopped paying the rent the Yearly Meeting in London had her evicted.[20] The Quaker presence disappeared from Dutch life by the early 1800s until reemerging in the 1920s, with Netherlands Yearly Meeting being established in 1931.[21]

The Friends had no ordained ministers and thus needed no seminaries for theological training. As a result, they did not open any colleges in the colonial period, and did not join in founding the University of Pennsylvania. The major Quaker colleges were Haverford College (1833), Earlham College (1847), Swarthmore College (1864), and Bryn Mawr College (1885), all founded much later.[22] The Friends did start the first elementary schools in Pennsylvania, Penn Charter (1689), Darby Friends School (1692) and Abington (1696).[23]

Persecution and acceptance in the New World

In 1657 some Quakers were able to find refuge to practice in Providence Plantations established by Roger Williams.[24] Other Quakers faced persecution in Puritan Massachusetts. In 1656 Mary Fisher and Ann Austin began preaching in Boston. They were considered heretics because of their insistence on individual obedience to the Inner Light. They were imprisoned and banished by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Their books were burned, and most of their property was confiscated. They were imprisoned under terrible conditions, then deported.[25]

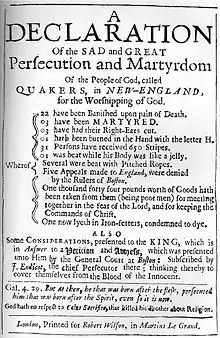

Some Quakers in New England were only imprisoned or banished. A few were also whipped or branded. Christopher Holder, for example, had his ear cut off. A few were executed by the Puritan leaders, usually for ignoring and defying orders of banishment. Mary Dyer was thus executed in 1660. Three other martyrs to the Quaker faith in Massachusetts were William Robinson, Marmaduke Stephenson, and William Leddra. These events are described by Edward Burrough in A Declaration of the Sad and Great Persecution and Martyrdom of the People of God, called Quakers, in New-England, for the Worshipping of God (1661). Around 1667, the English Quaker preachers Alice and Thomas Curwen, who had been busy in Rhode Island and New Jersey, were imprisoned in Boston under Massachusetts law and publicly flogged.[26]

In 1657 a group of Quakers from England landed in New Amsterdam. One of them, Robert Hodgson, preached to large crowds of people. He was arrested, imprisoned, and flogged. Governor Peter Stuyvesant issued a harsh ordinance, punishable by fine and imprisonment, against anyone found guilty of harboring Quakers. Some sympathetic Dutch colonists were able to get him released. Almost immediately after the edict was released, Edward Hart, the town clerk in what is now Flushing, New York, gathered his fellow citizens on Dec. 27, 1657 and wrote a petition to Stuyvesant, called the Flushing Remonstrance, citing the Flushing town charter of 1645, which promised liberty of conscience. Stuyvesant arrested Hart and the other official who presented the document to him, and he jailed two other magistrates who had signed the petition, and also forced the other signatories to recant. But Quakers continued to meet in Flushing. Stuyvesant arrested a farmer, John Bowne, in 1662 for holding illegal meetings in his home and banished him from the colony; Bowne immediately went to Amsterdam to plead for the Quakers. Though the Dutch West India Company called Quakerism an "abominable religion", it nevertheless overruled Stuyvesant in 1663 and ordered him to "allow everyone to have his own belief".[27]

Sandwhich and Daniel Wing

In Bowden’s History of the Society of Friends in America, it is mentioned that “two English Friends, named Christopher Holden and John Copeland came to Sandwhich on the 20th of the 6th month” of 1657[28] and there they found friends of toleration and resisters of an oppressive law in Daniel Wing, the son of John Wing and Deborah Bachiler, and grandson of Stephen Bachiler. Daniel Wing and his brother Stephen Wing and others resisted an oppressive law in the town of Sandwhich which publicly punished men and women by whipping, for “meetings at private houses, for encouraging others in holding meetings, for entertaining the preachers and for the unworthy speeches”. By 1658, Daniel Wing, with others who acted with him, became active converts and there were 18 families who recorded their names in the documents of the society. Writers of 1658-1660 said “We have two strong places in this land, the one at Newport and the other at Sandwhich; almost the whole town of Sandwhich is adhering towards them” and the records of the Monthly Meetings of Friends show that the Sandwhich Monthly Meeting was the first established in America. [29]

William Penn and settlement in colonial Pennsylvania

William Penn, a colonist to whom the king owed money, received ownership of Pennsylvania in 1681, which he tried to make a "holy experiment" by a union of temporal and spiritual matters. Pennsylvania made guarantees of religious freedom, and kept them, attracting many Quakers and others. Quakers took political control but were bitterly split on the funding of military operations or defenses; finally they relinquished political power. They created a second "holy experiment" by extensive involvement in voluntary benevolent associations while remaining apart from government. Programs of civic activism included building schools, hospitals and asylums for the entire city. Their new tone was an admonishing moralism born from a feeling of crisis. Even more extensive philanthropy was possible because of the wealth of the Quaker merchants based in Philadelphia.[30]

The Quakers did not want to provide military troops to defend frontier settlements. They passed a bill that gave themselves the authority to appoint commissioners to oversee provincial Indian agents, interpreters, traders, and the legal means to build their own trade posts. In April 1756, a group of Philadelphia Quakers formed the Friendly Association for Regaining and Preserving Peace with the Indians by Pacific Measures. Its purpose was to fulfill the legacy of William Penn's "Holy Experiment", which included "preserving the Friendship of the Indians. The association provided funding for commissioners of Indian affairs helping the Quakers control Indian diplomacy and trade in Pennsylvania.[31]

Eighteenth century

In 1691 George Fox died. Thus the Quaker movement went into the 18th century without one of its most influential early leaders. Thanks to the Toleration Act of 1689, people in Great Britain were no longer criminals simply by being Friends.

During this time, other people began to recognize Quakers for their integrity in social and economic matters. Many Quakers went into manufacturing or commerce. These Quaker businessmen were successful, in part, because people trusted them. The customers knew that Quakers felt a strong conviction to set a fair price for goods and not to haggle over prices. They also knew that Quakers were committed to quality work, and that what they produced would be worth the price.

Some useful and popular products made by Quaker businesses at that time included iron and steel by Abraham Darby II and Abraham Darby III and pharmaceuticals by William Allen. An early meeting house was set up in Broseley, Shropshire by the Darbys.

American colonies

In North America, Quakers, like other religious groups, were involved in the migration to the frontier. Initially this involved moves south from Pennsylvania and New Jersey along the Great Wagon Road. Historic meeting houses such as the 1759 Hopewell Friends Meeting House in Frederick County, Virginia and Lynchburg, Virginia's 1798 South River Friends Meetinghouse stand as testaments to the expanding borders of American Quakerism.[32] From Maryland and Virginia, Quakers moved to the Carolinas and Georgia. In later years, they moved to the Northwest Territory and further west.

Social reform

Quakers were becoming more concerned about social issues and becoming more active in society at large. Slavery (considered below) was the most controversial issue.

Another issue that became a concern of Quakers was the treatment of the mentally ill. Tea merchant, William Tuke opened the Retreat at York in 1796. It was a place where the mentally ill were treated with the dignity that Friends believe is inherent in all human beings. Most asylums at that time forced such people into deplorable conditions and did nothing to help them.

The Quakers' commitment to pacifism came under attack during the American Revolution, as many of those living in the Thirteen Colonies struggled with conflicting ideals of patriotism for the new United States and their rejection of violence. Despite this dilemma, a significant number still participated in some form, and there were many Quakers involved in the American Revolution.

By the late 18th century, Quakers were sufficiently recognized and accepted that the United States Constitution contained language specifically directed at Quaker citizens—in particular, the explicit allowance of "affirming", as opposed to "swearing" various oaths.

The abolition of slavery

Most Quakers did not oppose owning slaves when they first came to America. To most Quakers, "slavery was perfectly acceptable provided that slave owners attended to the spiritual and material needs of those they enslaved".[33] 70% of the leaders of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting owned slaves in the period from 1681 to 1705; however, from 1688 some Quakers began to speak out against slavery.

John Blunston, Quaker pioneer founder of Darby Borough, Pennsylvania; and 12th Speaker of the PA Colonial Assembly; took part in an early action against slavery in 1715.

In The Friend, Vol. 28:309 there is text of a "minute made in 'that Quarterly Meeting held at Providence Meeting-house the first day of the Sixth month, 1715' ." It reads as follows "A weighty concern coming before the meeting concerning some Friends being yet in the practice of importing, buying and selling negroe slaves; after some time spent in a solid and serious consideration thereof, it is the unanimous sense and judgment of this meeting, that Friends be not concerned in the importing, buying or selling of any negro slaves that shall be imported in future; and that the same be laid before the next Yearly Meeting desiring their concurrence therein. Signed by order and on behalf of the Meeting, Caleb Pusey, Jno. Wright,Nico. Fairlamb, Jno. Blunsten"

The Germantown (Pennsylvania) Monthly Meeting published its opposition to slavery in 1688, but abolitionism did not become universal among Quakers until the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting reached unity on the issue in 1754. Reaching unity (spiritual consensus) was a long and difficult process. William Penn himself owned slaves. Some Quaker businessmen had made their fortunes in Barbados or owned ships that worked the British/West Indies/American triangle. But gradually the reality of slavery took hold and the promotion by concerned members such as John Woolman in the early 18th century changed things. Woolman was a farmer, retailer, and tailor from New Jersey who became convinced that slavery was wrong and published the widely read "John Woolman's Journal". He wrote: "...Slaves of this continent are oppressed, and their cries have reached the ears of the Most High. Such are the purity and certainty of his judgments, that he cannot be partial to our favor." In general Quakers opposed mistreatment of slaves[34][35] and promoted the teaching of Christianity and reading to them. Woolman argued that the entire practice of buying, selling, and owning human beings was wrong in principle. Other Quakers started to agree and became very active in the abolition movement. Other Quakers who ministered against slavery were not so moderate. Benjamin Lay would minister passionately and personally and once sprayed fake blood on the congregation, a ministry which got him disowned. After initially finding agreement that they would buy no slaves off the boats, the entire society came to unity (spiritual consensus) on the issue in 1755, after which time no one could be a Quaker and own a slave. In 1790, one of the first documents received by the new Congress was an appeal by the Quakers (presented through Benjamin Franklin) to abolish slavery in the United States.

By 1756 only 10% of leaders of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting owned slaves.[36] Virginia was a bastion of slaveholding. In 1765, the Quaker minister John Griffith wrote that " the life of religion is almost lost where slaves are numerous..the practice being as contrary to the spirit of Christianity as light is to darkness"

Two other early prominent Friends to denounce slavery were Anthony Benezet and John Woolman. They asked the Quakers, "What thing in the world can be done worse towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away and sell us for slaves to strange countries".[37] In that same year, a group of Quakers along with some German Mennonites met at the meeting house in Germantown, Pennsylvania, to discuss why they were distancing themselves from slavery. Four of them signed a document written by Francis Daniel Pastorius that stated, "To bring men hither, or to rob and sell them against their will, we stand against."[38]

From 1755 to 1776, the Quakers worked at freeing slaves, and became the first Western organization to ban slaveholding.[35] They also created societies to promote the emancipation of slaves.[39] From the efforts of the Quakers, Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were able to convince the Continental Congress to ban the importation of slaves into America as of December 1, 1775. Pennsylvania was the strongest anti-slavery state at the time, and with Franklin's help they led "The Pennsylvania Society for Promoting The Abolition of Slavery, The Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, and for Improving the Condition of the African Race" (Pennsylvania Abolition Society).[37] In November 1775, Virginia's royal governor announced that all slaves would be freed if they were willing to fight for Great Britain (Dunmore's Proclamation). This encouraged George Washington to allow slaves to enlist as well, so that they all did not try to run away and fight on the Royalist side to get their freedom (Black Patriot). About five thousand African Americans served for the Continental Army and thus gained their freedom. By 1792 states from Massachusetts to Virginia all had similar anti-slavery groups. From 1780 to 1804, slavery was largely abolished in all of New England, the Middle Atlantic states, and the North West territories.

The Southern states, however, were still very prominent in keeping slavery running. Because of this, an informal network of safe houses and escape routes—called the Underground Railroad—developed across the United States to get enslaved people out of America and into Canada (British North America) or the free states. The Quakers were a very prominent force [40][41] in the Underground Railroad, and their efforts helped free many slaves. Immediately north of the Mason-Dixon line, the Quaker settlement of Chester County, Pennsylvania—one of the early hubs of the Underground Railroad—was considered a "hotbed of abolition". However, not all Quakers were of the same opinion regarding the Underground Railroad: because slavery was still legal in many states, it was therefore illegal for anyone to help a slave escape and gain freedom. Many Quakers, who saw slaves as equals, felt it was proper to help free slaves and thought that it was unjust to keep someone as a slave; many Quakers would "lie" to slave hunters when asked if they were keeping slaves in their house, they would say "no" because in their mind there was no such thing as a slave. Other Quakers saw this as breaking the law and thereby disrupting the peace, both of which go against Quaker values thus breaking Quaker belief in being pacifistic. Furthermore, involvement with the law and the government was something from which the Quakers had tried to separate themselves. This divisiveness caused the formation of smaller, more independent branches of Quakers, who shared similar beliefs and views.

However, there were many prominent Quakers who stuck to the belief that slavery was wrong, and were even arrested for helping the slaves out and breaking the law. Richard Dillingham, a school teacher from Ohio, was arrested because he was found helping three slaves escape in 1848. Thomas Garrett had an Underground Railroad stop at his house in Delaware and was found guilty in 1848 of helping a family of slaves escape. Garrett was also said to have helped and worked with Harriet Tubman, who was a very well-known slave who worked to help other slaves gain their freedom. Educator Levi Coffin and his wife Catherine were Quakers who lived in Indiana and helped the Underground Railroad by hiding slaves in their house for over 21 years. They claimed to have helped 3,000 slaves gain their freedom.[38] [42] Susan B. Anthony was also a Quaker, and did a lot of antislavery work hand in hand with her work with women's rights.

Free Quakers

A small breakaway group, the Religious Society of Free Quakers, originally called "The Religious Society of Friends, by some styled the Free Quakers", was established on February 20, 1781 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. More commonly known as Free Quakers, the Society was founded by Quakers who had been expelled for failure to adhere to the Peace Testimony during the American Revolution.[43]

Notable Free Quakers at the early meetings include Lydia Darragh and Betsy Ross. After 1783, the number of Free Quakers began to dwindle as some members died and others were either accepted back into the Society of Friends or by other religious institutions. The movement had died out by the 1830s.[44]

Nineteenth century

Quaker influence on society

During the 19th century, Friends continued to influence the world around them. Many of the industrial concerns started by Friends in the previous century continued as detailed in Milligan's Biographical dictionary of British Quakers in commerce and industry, with new ones beginning. Friends also continued and increased their work in the areas of social justice and equality. They made other contributions as well in the fields of science, literature, art, law and politics.

In the realm of industry Edward Pease opened the Stockton and Darlington Railway in northern England in 1825. It was the first modern railway in the world, and carried coal from the mines to the seaports. Henry and Joseph Rowntree owned a chocolate factory in York, England. When Henry died, Joseph took it over. He provided the workers with more benefits than most employers of his day. He also funded low-cost housing for the poor. John Cadbury founded another chocolate factory, which his sons George and Richard eventually took over. A third chocolate factory was founded by Joseph Storrs Fry in Bristol. The shipbuilder John Wigham Richardson was a prominent Newcastle upon Tyne Quaker. His office at the centre of the shipyard was always open to his workers for whom he cared greatly and he was a founder of the Workers’ Benevolent Trust in the region, (a forerunner to the trades’ union movement). Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson, the builders of the RMS Mauretania, refused to build war ships on account of his pacifist beliefs.

Quakers actively promoted equal rights during this century as well. As early as 1811, Elias Hicks published a pamphlet showing that slaves were "prize goods"—that is, products of piracy—and hence profiting from them violated Quaker principles; it was a short step from that position to reject use of all products made from slave labour, the free produce movement that won support among Friends and others but also proved divisive. Quaker women such as Lucretia Mott and Susan B. Anthony joined the movement to abolish slavery, moving them to cooperate politically with non-Quakers in working against the institution. Somewhat as a result of their initial exclusion from abolitionist activities, they changed their focus to the right of women to vote and influence society. Thomas Garrett led in the movement to abolish slavery, personally assisting Harriet Tubman to escape from slavery and to coordinate the Underground Railroad. Richard Dillingham died in a Tennessee prison where he was incarcerated for trying to help some slaves escape. Levi Coffin was also an active abolitionist, helping thousands of escaped slaves migrate to Canada and opening a store for selling products made by former slaves.

Prison reform was another concern of Quakers at that time. Elizabeth Fry and her brother Joseph John Gurney campaigned for more humane treatment of prisoners and for the abolition of the death penalty. They played a key role in forming the Association for the Improvement of the Female Prisoners in Newgate, which managed to better the living conditions of woman and children held at the prison. Their work raised concerns about the prison system as a whole, so that they were a factor behind Parliament eventually passing legislation to improve conditions further and decrease the number of capital crimes.

In the early days of the Society of Friends, Quakers were not allowed to get an advanced education. Eventually some did get opportunities to go to university and beyond, which meant that more and more Quakers could enter the various fields of science. Thomas Young an English Quaker, did experiments with optics, contributing much to the wave theory of light. He also discovered how the lens in the eye works and described astigmatism and formulated an hypothesis about the perception of color. Young was also involved in translating the Rosetta Stone. He translated the demotic text and began the process of understanding the hieroglyphics. Maria Mitchell was an astronomer who discovered a comet. She was also active in the abolition movement and the women's suffrage movement. Joseph Lister promoted the use of sterile techniques in medicine, based on Pasteur's work on germs. Thomas Hodgkin was a pathologist who made major breakthroughs in the field of anatomy. He was the first doctor to describe the type of lymphoma named after him. An historian, he was also active in the movement to abolish slavery and to protect aboriginal people. John Dalton formulated the atomic theory of matter, among other scientific achievements.

Quakers were not apt to participate publicly in the arts. For many Quakers these things violated their commitment to simplicity and were thought too "worldly". Some Quakers, however, are noted today for their creative work. John Greenleaf Whittier was an editor and a poet in the United States. Among his works were some poems involving Quaker history and hymns expressing his Quaker theology. He also worked in the abolition movement. Edward Hicks painted religious and historical paintings in the naive style and Francis Frith was a British photographer, whose catalogue ran to many thousands of topographical views.

At first Quakers were barred by law and their own convictions from being involved in the arena of law and politics. As time went on, a few Quakers in England and the United States did enter that arena. Joseph Pease was the son of Edward Pease mentioned above. He continued and expanded his father's business. In 1832 he became the first Quaker elected to Parliament. Noah Haynes Swayne was the only Quaker to serve on the United States Supreme Court. He was an Associate Justice from 1862 to 1881. He strongly opposed slavery, moving out of the slave-holding state of Virginia to the free state of Ohio in his young adult years.

Theological schisms

Quakers found that theological disagreements over doctrine and evangelism had left them divided into the Gurneyites, who questioned the applicability of early Quaker writings to the modern world, and the conservative Wilburites. Wilburites not only held to the writings of Fox (1624–91) and other early Friends, they actively sought to bring not only Gurneyites, but Hicksites, who had split off during the 1820s over antislavery and theological issues, back to orthodox Quaker belief.[45] Apart from theology there were social and psychological patterns revealed by the divisions. The main groups were the growth-minded Gurneyites, Orthodox Wilburites, and reformist Hicksites. Their differences increased after the Civil War (1861–65), leading to more splintering. The Gurneyites became more evangelical, embraced Methodist-like revivalism and the Holiness Movement, and became probably the leading force in American Quakerism. They formally endorsed such radical innovations as the pastoral system. Neither the Hicksites nor Wilburites experienced such numerical growth. The Hicksites became more liberal and declined in number, while the Wilburites remained both orthodox and divided.[46]

During the Second Great Awakening after 1839 Friends began to be influenced by the revivals sweeping the United States. Robert Pearsall Smith and his wife Hannah Whitall Smith, Quakers from New Jersey, had a profound effect. They promoted the Wesleyan idea of Christian perfection, also known as holiness or sanctification, among Quakers and among various denominations. Their work inspired the formation of many new Christian groups. Hannah Smith was also involved in the movements for women's suffrage and for temperance.

Hicksites

The Society in Ireland, and later, the United States suffered a number of schisms during the 19th century. In 1827–28, the views and popularity of Elias Hicks resulted in a division within five-yearly meetings, Philadelphia, New York, Ohio, Indiana, and Baltimore. Rural Friends, who had increasingly chafed under the control of urban leaders, sided with Hicks and naturally took a stand against strong discipline in doctrinal questions. Those who supported Hicks were tagged as "Hicksites", while Friends who opposed him were labeled "Orthodox". The latter had more adherents overall, but were plagued by subsequent splintering. The only division the Hicksites experienced was when a small group of upper-class and reform-minded Progressive Friends of Longwood, Pennsylvania, emerged in the 1840s; they maintained a precarious position for about a century.[47]

Gurneyites

In the early 1840s the Orthodox Friends in America were exercised by a transatlantic dispute between Joseph John Gurney of England and John Wilbur of Rhode Island. Gurney, troubled by the example of the Hicksite separation, emphasized Scriptural authority and favored working closely with other Christian groups. Wilbur, in response, defended the authority of the Holy Spirit as primary, and worked to prevent the dilution of the Friends tradition of Spirit-led ministry. After privately criticizing Gurney in correspondence to sympathetic Friends, Wilbur was expelled from his yearly meeting in a questionable proceeding in 1842. Probably the best known Orthodox Friend was the poet and abolitionist editor John Greenleaf Whittier. Over the next several decades, a number of Wilburite–Gurneyite separations occurred.[48]

Starting in the late 19th century, many American Gurneyite Quakers, led by Dougan Clark Jr., adopted the use of paid pastors, planned sermons, revivals, hymns and other elements of Protestant worship services. They left behind the old "plain style".[49] This type of Quaker meeting is known as a "programmed meeting". Worship of the traditional, silent variety is called an "unprogrammed meeting", although there is some variation on how the unprogrammed meetings adhere strictly to the lack of programming. Some unprogrammed meetings may have also allocated a period of hymn-singing or other activity as part of the total period of worship, while others maintain the tradition of avoiding all planned activities. (See also Joel Bean.)

Beaconites

For the most part, Friends in Britain were strongly evangelical in doctrine and escaped these major separations, though they corresponded only with the Orthodox and mostly ignored the Hicksites.[50]

The Beaconite Controversy arose in England from the book A Beacon to the Society of Friends, published in 1835 by Isaac Crewdson. He was a Recorded Minister in the Manchester Meeting. The controversy arose in 1831 when doctrinal differences amongst the Friends culminated in the winter of 1836–1837 with the resignation of Isaac Crewdson and 48 fellow members of the Manchester Meeting. About 250 others left in various localities in England, including some prominent members. A number of these joined themselves to the Plymouth Brethren and brought influences of simplicity of worship to that society. Those notable among the Plymouthists who were former Quakers included John Eliot Howard of Tottenham and Robert Mackenzie Beverley.

Native Americans

The Quakers were involved in many of the great reform movements of the first half of the 19th century. After the Civil War they won over President Grant to their ideals of a just policy toward the American Indians, and became deeply involved in Grant's "Peace Policy". Quakers were motivated by high ideals, played down the role of conversion to Christianity, and worked well side by side with the Indians. They had been highly organized and motivated by the anti-slavery crusade, and after the Civil War were poised to expand their energies to include both ex-slaves and the western tribes. They had Grant's ear and became the principal instruments for his peace policy. During 1869–85, they served as appointed agents on numerous reservations and superintendencies in a mission centered on moral uplift and manual training. Their ultimate goal of acculturating the Indians to American culture was not reached because of frontier land hunger and Congressional patronage politics.[51]

Twentieth-century developments

During the 20th century, Quakerism was marked by movements toward unity, but at the end of the century Quakers were more sharply divided than ever. By the time of the First World War, almost all Quakers in Britain and many in the United States found themselves committed to what came to be called "liberalism", which meant primarily a religion that de-emphasized corporate statements of theology and was characterized by its emphasis on social action and pacifism. Hence when the two Philadelphia and New York Yearly Meetings, one Hicksite, one Orthodox, united in 1955—to be followed in the next decade by the two in Baltimore Yearly Meeting—they came together on the basis of a shared liberalism. As time wore on and the implication of this liberal change became more apparent, lines of division between various groups of Friends became more accentuated.

World War I at first produced an effort toward unity, embodied in the creation of the American Friends Service Committee in 1917 by Orthodox Friends, led by Rufus Jones and Henry Cadbury. A Friends Service Committee, as an agency of London Yearly Meeting, had already been created in Britain to help Quakers there deal with problems of military service; it continues today, after numerous name changes, as Quaker Peace & Social Witness. Envisioned as a service outlet for conscientious objectors that could draw support from across diverse yearly meetings, the AFSC began losing support from more evangelical Quakers as early as the 1920s and served to emphasize the differences between them, but prominent Friends such as Herbert Hoover continued to offer it their public support. Many Quakers from Oregon, Ohio, and Kansas became alienated from the Five Years Meeting (later Friends United Meeting), considering it infected with the kind of theological liberalism that Jones exemplified; Oregon Yearly Meeting withdrew in 1927.[52] That same year, eleven evangelicals met in Cheyenne, Wyoming, to plan how to resist the influence of liberalism, but depression and war prevented another gathering for twenty years, until after the end of the second world war.

To overcome such divisions, liberal Quakers organized so-called worldwide conferences of Quakers in 1920 in London and again in 1937 at Swarthmore and Haverford Colleges in Pennsylvania, but they were too liberal and too expensive for most evangelicals to attend. A more successful effort at unity was the Friends Committee on National Legislation, originating during World War II in Washington, D.C., as a pioneering Quaker lobbying unit. In 1958 the Friends World Committee for Consultation was organized to form a neutral ground where all branches of the Society of Friends could come together, consider common problems, and get to know one another; it held triennial conferences that met in various parts of the world, but it had not found a way to involve very many grassroots Quakers in its activities. One of its agencies, created during the Cold War and known as Right Sharing of World Resources, collects funds from Quakers in the "first world" to finance small self-help projects in the "Third World", including some supported by Evangelical Friends International. Beginning in 1955 and continuing for a decade, three of the yearly meetings divided by the Hicksite separation of 1827, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York, as well as Canadian Yearly Meeting, reunited.

Disagreements between the various Quaker groups, Friends United Meeting, Friends General Conference, Evangelical Friends International, and Conservative yearly meetings, involved both theological and more concrete social issues. FGC, founded in 1900[53] and centered primarily in the East, along the West coast, and in Canada, tended to be oriented toward the liberal end of the political spectrum, was mostly unprogrammed, and aligned itself closely with the American Friends Service Committee. By the last part of the century it had taken a strong position in favor of same-sex marriage, was supportive of gay rights, and usually favored a woman's right to choose an abortion. Its membership tended to be professional and middle class or higher.

Rooted in the Midwest, especially Indiana, and North Carolina, FUM was historically more rural and small-town in its demographics. The Friends churches which formed part of this body were predominantly programmed and pastoral. Though a minority of its yearly meetings (New York, New England, Baltimore, Southeastern and Canada) were also affiliated with Friends General Conference and over the decades became more theologically liberal and predominantly unprogrammed in worship style, the theological position of the majority of its constituent yearly meetings continues to be often similar in flavor to the Protestant Christian mainstream in Indiana and North Carolina. In 1960, a theological seminary, Earlham School of Religion, was founded in FUM's heartland—Richmond, Indiana—to offer ministerial training and religious education.[54] The seminary soon came to enroll significant numbers of unprogrammed Friends, as well as Friends from pastoral backgrounds.

EFI was staunchly evangelical and by the end of the century had more members converted through its missionary endeavors abroad than in the United States; Southwest Friends Church illustrated the group's drift away from traditional Quaker practice, permitting its member churches to practice the outward ordinances of the Lord's Supper and baptism. On social issues its members exhibited strong antipathy toward homosexuality and enunciated opposition to abortion. At century's end, Conservative Friends held onto only three small yearly meetings, in Ohio, Iowa, and North Carolina, with Friends from Ohio arguably the most traditional. In Britain and Europe, where institutional unity and almost universal unprogrammed worship style were maintained, these distinctions did not apply, nor did they in Latin America and Africa, where evangelical missionary activity predominated.

In the 1960s and later, these categories were challenged by a mostly self-educated Friend, Lewis Benson, a New Jersey printer by training, a theologian by vocation. Immersing himself in the corpus of early Quaker writings, he made himself an authority on George Fox and his message. In 1966, Benson published Catholic Quakerism, a small book that sought to move the Society of Friends to what he insisted was a strongly pro-Fox position of authentic Christianity, entirely separate from theological liberalism, churchly denominationalism, or rural isolation. He created the New Foundation Fellowship, which blazed forth for a decade or so, but had about disappeared as an effective group by the end of the century.

By that time, the differences between Friends were quite clear, to each other if not always to outsiders. Theologically, a small minority of Friends among the "liberals" expressed discomfort with theistic understandings of the Divine, while more evangelical Friends adhered to a more biblical worldview. Periodical attempts to institutionally reorganize the disparate Religious Society of Friends into more theologically congenial organizations took place, but generally failed. By the beginning of the 21st century, Friends United Meeting, as the middle ground, was suffering from these efforts, but still remained in existence, even if it did not flourish. In its home base of yearly meetings in Indiana especially, it lost numerous churches and members, both to other denominations and to the evangelicals.

Quakers in Britain and the Eastern United States embarked on efforts in the field of adult education, creating three schools with term-long courses, week-end activities, and summer programs. Woodbrooke College began in 1903 at the former home of chocolate magnate George Cadbury in Birmingham, England, and later became associated with the University of Birmingham, while Pendle Hill, in the Philadelphia suburb of Wallingford, did not open until 1930. Earlier, beginning in 1915 and continuing for about a decade, the Woolman School had been created by Philadelphia Hicksites near Swarthmore College; its head, Elbert Russell, a midwestern recorded minister, tried unsuccessfully to maintain it, but it ended in the late 1920s. All three sought to educate adults for the kind of lay leadership that the founders Society of Friends relied upon. Woodbrooke and Pendle Hill still maintain research libraries and resources.

During the 20th century, two Quakers, Herbert Hoover and Richard Nixon, both from the Western evangelical wing, were elected to serve as presidents of the United States, thus achieving more secular political power than any Friend had enjoyed since William Penn.

Kindertransport

In 1938–1939, just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, 10,000 European Jewish children were given temporary resident visas for the UK, in what became known as the Kindertransport. This allowed these children to escape the Holocaust. American Quakers played a major role in pressuring the British government to supply these visas. The Quakers chaperoned the Jewish children on the trains, and cared for many of them once they arrived in Britain.[55]

War Rescue Operations, and The One Thousand Children

Before and during the Second World War, the Quakers, often working with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee or Œuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE), helped in the rescue from Europe of mainly Jewish families of refugees, in their flight finally to America. But in some cases, only the children could escape—these mainly Jewish children fled unaccompanied, leaving their parents behind, generally to be murdered by the Nazis. Such children are part of the One Thousand Children, actually numbering about 1400. Quakers were nominated five times, starting from 1912, by the Nobel Peace Prize Committee[56] for "...their pioneering work in the international peace movement and compassionate effort to relieve human suffering."[57]

Costa Rica

In 1951 a group of Quakers, objecting to the military conscription, emigrated from the United States to Costa Rica and settled in what was to become Monteverde. The Quakers founded a cheese factory and a Friends' school, and in an attempt to protect the area's watershed, purchased much of the land that now makes up the Monteverde Reserve. The Quakers have played a major role in the development of the community.[58]

See also

References

- Christian Scholar's Review, Volume 27. Hope College. 1997. p. 205.

This was especially true of proto-evangelical movements like the Quakers, organized as the Religious Society of Friends by George Fox in 1668 as a group of Christians who rejected clerical authority and taught that the Holy Spirit guided

- Manual of Faith and Practice of Central Yearly Meeting of Friends. Central Yearly Meeting of Friends. 2018. p. 2.

- "Jocelyn Bell Burnell", Wikipedia, 2023-01-30, retrieved 2023-02-16

- "Maria Mitchell", Wikipedia, 2023-01-08, retrieved 2023-02-16

- Ingle, H. Larry (1996). First Among Friends: George Fox and the Creation of Quakerism.

- Damrosch, Leo (1996). The Sorrows of the Quaker Jesus: James Nayler and the Puritan Crackdown on the Free Spirit, pp. 66, 221

- Moore, Rosemary (2000). The Light in Their Consciences: Faith, Practices, and Personalities in Early British Quakerism, (1646–1666).

- Moore, Rosemary The Light in Their Consciences: The Early Quakers in Britain, 1646–1666, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press (2000) pp. 224–26.

- Orlando Project site: Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- Virginia Blain, Patricia Clements and Isobel Grundy, eds: The Feminist Companion to Literature in English (London: Batsford, 1990), entry on Dorcas Dole, p. 302.

- Taylor, Kay S. (2001). "The Role of Quaker Women in the Seventeenth Century, and the Experiences of the Wiltshire Friends." Southern History 23: 10–29. ISSN 0142-4688

- George Fox's Imprisonment

- Charles II, 1662: An Act for preventing the Mischeifs and Dangers that may arise by certaine Persons called Quakers and others refusing to take lawfull Oaths, Statutes of the Realm: volume 5: 1628–80. 1819. pp. 350, 351. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- Ingle, First Among Friends, 212–14

- Catholic Encyclopedia 1917, Entry on Society of Friends

- Lodge, Richard The History of England – From the Restoration to the Death of William III 1660–1702 (1910). p. 268

- Hull, William I. (1938). The Rise of Quakerism in Amsterdam, 1655–1665. Swarthmore College. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- Hull, William Isaac (1970). William Penn and the Dutch Quaker Migration to Pennsylvania. Genealogical Publishing Com. ISBN 9780806304328. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- British Travellers in Holland During the Stuart Period: Edward Browne and John Locke As Tourists in the United Provinces. Brill. 1993. p. 203. ISBN 9789004094826. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- Kannegieter, J. Z. (1972). Geschiedenis van de Vroegere Quackergemeenschap te Amsterdam. Scheltema & Holkema. p. 326. ISBN 9789060608890. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- Handbook of the Religious Society of Friends. 1952. pp. 38, 40. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- Yount, David (2007). How the Quakers invented America. pp. 83–4

- Woody, Thomas (1920). Early Quaker education in Pennsylvania. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

- The Colonies Rhode Island (Est. 1636)

- Baltzell, Edward Digby (1996). Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. p. 86.

- Mullett, Michael (2004). "Curwen, Thomas (c. 1610–1680)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, UK: OUP) Retrieved 17 November 2015

- Jackson, Kenneth T. (December 27, 2007). "A Colony With a Conscience". The New York Times.

- Bowden, James (1850). History of the Society of Friends in America (Volume 1 ed.). London: Richard Bartlet Printer. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Pierce, Frederic Clifton (2013). Batchelder, Batcheller Genealogy, Descendants of Rev. Stephen Bachiller of England (1898 ed.). New Dehli, India: Isha Books. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9789333137287.

- Illick, Joseph E. (1976). Colonial Pennsylvania: A History. p. 225.

- Merritt, Jane (2003). At the Crossroads: Indians and Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Frontier, 1700-1763. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. pp. 203–204.

- Harold Wickliffe Rose. The Colonial House of Worship in America. New York: Hastings House, Publishers, 1963, p. 518.

- Wood, Betty Slavery in colonial America, 1619–1776 AltaMira Press (2005) p. 14.

- "Quakers (Society of Friends)". The Abolition Project. 2009.

- Moore Mueller, Anne (2008). "John Woolman". web.tricolib.brynmawr.edu.

- Fischer, David Hackett Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America Oxford University Press (1989) p. 601.

- (Zuber 1993, 4)

- Ralph 2008

- (Marietta 1991, 894–896)

- Huffman, Jeanette (15 July 2017). Starbuck, Waldschmidt, & Huffman Family of Bangor, Michigan. p. 59. ISBN 9781387103201.

- "THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD". Indiana Historical Bureau. 15 December 2020.

- Levi Coffin (1880). Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, the Reputed President of the Underground Railroad: Being a Brief History of the Labors of a Lifetime in Behalf of the Slave, with the Stories of Numerous Fugitives, who Gained Their Freedom Through His Instrumentality, and Many Other Incidents. Robert Clarke & Company. pp. 671, 705.

- William C. Kashatus, "The Quakers and the American Revolution." Quaker History 86.2 (1997): 58-59.

- Arthur J. Mekeel, "Free Quaker Movement in New England During the American Revolution." Bulletin of Friends' Historical Association 27.2 (1938): 72-82.

- Hamm, Thomas D. (2004). "'New Light on Old Ways': Gurneyites, Wilburites, and the Early Friends". Quaker History. 93 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1353/qkh.2004.0020. JSTOR 41947529. S2CID 162136169.

- Hamm, Thomas D. (2002). "The Divergent Paths of Iowa Quakers in the Nineteenth Century". Annals of Iowa. 61 (2): 125–150. doi:10.17077/0003-4827.10564.

- Doherty, Robert W. (1967). The Hicksite Separation A Sociological Analysis of Religious Schism in Early Nineteenth Century America.

- A Short History of Conservative Friends

- Kostlevy, William (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Holiness Movement. Scarecrow Press. p. 68. ISBN 9780810863187.

- For an account of how British Friends (London Yearly Meeting) transformed from evangelical to liberal Christian thinking, see Thomas C. Kennedy, British Quakerism 1860–1920: the transformation of a religious community (2001)

- Illick, Joseph E. (1971). "'Some of Our Best Friends Are Indians...': Quaker Attitudes and Actions Regarding the Western Indians during the Grant Administration". Western Historical Quarterly. 2 (3): 283–294. doi:10.2307/967835. JSTOR 967835.

- "Historical Summary" from Mid-America Yearly Meeting's Faith and Practice. Archived March 10, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "Locations of FGC Conferences and Gatherings" Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, FGC website.

- "Earlham School of Religion website". Archived from the original on 2010-05-29. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- Eve Nussbaum Soumerai and Carol D. Schulz, A voice from the Holocaust (2003) p. 53.

- "History | Quakers and the Nobel Peace Prize". quakernobel.org. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- "1947 Nobel Peace Laureate". Nobel Peace Prize. Norwegian Nobel Institute. 6 August 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- Mara Vorhees and Matthew Firestone, Costa Rica (2006) p. 187

- Further reading

- Abbott, Margery Post et al. Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers). (2003). 432 pp.

- Bacon, Margaret Hope. "Quakers and Colonization," Quaker History, 95 (Spring 2006), 26–43. JSTOR 41947575.

- Barbour, Hugh, and J. William Frost. The Quakers. (1988), 412pp; historical survey, including many capsule biographies online edition

- Barbour, Hugh. The Quakers in Puritan England (1964).

- Benjamin, Philip. Philadelphia Quakers in an Age of Industrialism, 1870–1920 (1976),

- Braithwaite, William C. The Beginnings of Quakerism (1912); revised by Henry J. Cadbury (1955) online edition

- Braithwaite, William C. Second Period of Quakerism (1919); revised by Henry Cadbury (1961), covers 1660 to 1720s in Britain

- Brock, Peter. Pioneers of the Peaceable Kingdom (1968), on Peace Testimony from the 1650s to 1900.

- Bronner, Edwin B. William Penn's Holy Experiment (1962)

- Connerley, Jennifer. "Friendly Americans: Representing Quakers in the United States, 1850–1920." PhD dissertation U. of North Carolina, Chapel Hill 2006. 277 pp. Citation: DAI 2006 67(2): 600-A. DA3207363 online at ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Dandelion, Pink. The Quakers: A Very Short Introduction (2008). ISBN 978-0-19-920679-7.

- Davies, Adrian. The Quakers in English Society, 1655–1725. (2000). 261 pp.

- Doherty, Robert. The Hicksite Separation (1967), uses the new social history to inquire who joined which side

- Dunn, Mary Maples. William Penn: Politics and Conscience (1967).

- Frost, J. William. The Quaker Family in Colonial America: A Portrait of the Society of Friends (1973), emphasis on social structure and family life.

- Frost, J. William. "The Origins of the Quaker Crusade against Slavery: A Review of Recent Literature," Quaker History 67 (1978): 42–58. JSTOR 41946850.

- Hamm, Thomas. The Quakers in America. (2003). 293 pp., strong analysis of current situation, with brief history

- Hamm, Thomas. The Transformation of American Quakerism: Orthodox Friends, 1800–1907 (1988), looks at the effect of the Holiness movement on the Orthodox faction

- Hamm, Thomas D. Earlham College: A History, 1847–1997. (1997). 448 pp.

- Hewitt, Nancy. Women's Activism and Social Change (1984).

- Illick, Joseph E. Colonial Pennsylvania: A History. 1976. online edition

- Ingle, H. Larry Quakers in Conflict: The Hicksite Reformation (1986)

- Ingle, H. Larry. First among Friends: George Fox and the Creation of Quakerism. (1994). 407 pp.

- Ingle, H. Larry. Nixon's First Cover-up: The Religious Life of a Quaker President. (2015). 272 pp.

- James, Sydney. A People among Peoples: Quaker Benevolence in Eighteenth-Century America (1963), a broad ranging study that remains the best history in America before 1800.

- Jones, Rufus M., Amelia M. Gummere, and Isaac Sharpless. Quakers in the American Colonies (1911), history to 1775 online edition

- Jones, Rufus M. Later Periods of Quakerism, 2 vols. (1921), covers England and America until World War I.

- Jones, Rufus M. The Story of George Fox (1919) 169 pages online edition

- Jones, Rufus M. A Service of Love in War Time: American Friends Relief Work in Europe, 1917–1919 (1922) online edition

- Jordan, Ryan. "The Dilemma of Quaker Pacifism in a Slaveholding Republic, 1833–1865," Civil War History, Vol. 53, 2007 doi:10.1353/cwh.2007.0016. online edition

- Jordan, Ryan. Slavery and the Meetinghouse: The Quakers and the Abolitionist Dilemma, 1820–1865. (2007). 191 pp.

- Kashatus, William C. A Virtuous Education of Youth: William Penn and the Founding of Philadelphia's Schools (1997).

- Kashatus, William C. Conflict of Conviction: A Reappraisal of Quaker Involvement in the American Revolution (1990).

- Kashatus, William C. Abraham Lincoln, the Quakers and the Civil War: "A Trial of Faith and Principle" (2010).

- Kennedy, Thomas C. British Quakerism, 1860–1920: The Transformation of a Religious Community. (2001). 477 pp.

- Larson, Rebecca. Daughters of Light: Quaker Women Preaching and Prophesying in the Colonies and Abroad, 1700–1775. (1999). 399 pp.

- LeShana, James David. "'Heavenly Plantations': Quakers in Colonial North Carolina." PhD dissertation: U. of California, Riverside 1998. 362 pp. DAI 2000 61(5): 2005-A. DA9974014 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Milligan, Edward The Biographical dictionary of British Quakers in commerce and industry, 1775–1920, Sessions of York, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85072-367-7.

- Moore, Rosemary. The Light in Their Consciences: Faith, Practices, and Personalities in Early British Quakerism, (1646–1666), Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-271-01988-3.

- Nash, Gary. Quakers and Politics: Pennsylvania, 1680–1726 (1968).

- Punshon, John. Portrait in Grey: A short history of the Quakers. (Quaker Home Service, 1984).

- Rasmussen, Ane Marie Bak. A History of the Quaker Movement in Africa. (1994). 168 pp.

- Russell, Elbert. The History of Quakerism (1942). online edition

- Ryan, James Emmett. Imaginary Friends: Representing Quakers in American Culture, 1650–1950. (2009). ISBN 978-0-299-23174-3.

- Smuck, Harold. Friends in East Africa (Richmond, Indiana: 1987).

- Trueblood, D. Elton The People Called Quakers (1966).

- Tolles, Frederick B. Meeting House and Counting House (1948), on Quaker businessmen in colonial Philadelphia.

- Tolles, Frederick B. Quakers and the Atlantic Culture (1960).

- Vlach, John Michael. "Quaker Tradition and the Paintings of Edward Hicks: A Strategy for the Study of Folk Art," Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 94, 1981. doi:10.2307/540122. JSTOR 540122. online edition

- Walvin, James. The Quakers: Money and Morals. (1997). 243 pp.

- Yarrow, Clarence H. The Quaker Experience in International Conciliation (1979), for post–1945

- Primary sources

- Gummere, Amelia, ed. The Journal and Essays of John Woolman (1922) online edition

- Jones, Rufus M., ed. The Journal of George Fox: An Autobiography online edition

- Mott, Lucretia Coffin. Selected Letters of Lucretia Coffin Mott. edited by Beverly Wilson Palmer, U. of Illinois Press, 2002. 580 pp.

- West, Jessamyn, ed. The Quaker Reader (1962, reprint 1992) – collection of essays by Fox, Penn, and other notable Quakers

External links

- Quaker Heritage Press Reprints and on-line versions of classic Quaker works with links to works at other websites.

- Quaker Information Center

- A Quaker Page at the Street Corner Society

- Article by Bill Samuel on the Beginnings of Quakerism in quakerinfo.com

- Early Modern Quaker Texts Post-Reformation Digital Library