Quark (dairy product)

Quark or quarg is a type of fresh dairy product made from milk. The milk is soured, usually by adding lactic acid bacteria cultures, and strained once the desired curdling is achieved. It can be classified as fresh acid-set cheese. Traditional quark can be made without rennet, but in modern dairies small quantities of rennet are typically added. It is soft, white and unaged, and usually has no salt added.

Name

Quark is possibly described by Tacitus in his book Germania as lac concretum ("thick milk"), eaten by Germanic peoples.[1][2] However, this could also have meant soured milk or any other kind of fresh cheese or fermented milk product.

Although quark is sometimes referred to loosely as a type of "cottage cheese", they can be distinguished by the different production aspects and textural quality, with the cottage cheese grains described as more chewy or meaty.[3]

Etymology

The word Quark (Late Middle High German: quarc, twarc, zwarg;[4] Lower Saxon: dwarg[5]), with usage in German documented since the 14th century,[6][7] is thought to derive from a West Slavic equivalent,[6][7][8][9] such as Lower Sorbian twarog, Upper Sorbian twaroh, Polish twaróg, Czech and Slovak tvaroh.[8][10][11] The word is also cognate with Russian tvorog (творог) and Belarusian: tvaroh (тварог).[8][10][12]

The original Old Slavonic tvarogъ (тварогъ) is supposed to be related to the Church Slavonic творъ, tr. tvor, meaning "form".[13] The meaning can thus be interpreted as "milk that solidified and took a form".[14] The word formation is thus similar to that of the Italian formaggio and French fromage.[13]

- More cognates and forms

The Slavic words may also be cognate with the Greek name for cheese, τῡρός (tūrós).[13][15] A cognate term for quark, túró, is used in Hungarian.

Cognates also occur in Scandinavia (Danish kvark, Norwegian and Swedish kvarg) and the Netherlands (Dutch kwark). The Old English form is geþweor.[4]

Other German forms include Quarck,[16] and Quaergel (Quärgel).[17]

Production

Quark is a member of the acid-set cheese group, whose coagulation mainly relies on the acidity produced by lactic acid bacteria feeding on the lactose.[lower-alpha 1][18][19] But moderate amounts of rennet have also been in use, both at the home consumption level and the industrial level.[20][21]

Manufacture of quark normally uses pasteurized skim milk as the main ingredient, but cream can be added later to adjust fat content.[21][22][3] The lactic acid bacteria are introduced in the form of mesophilic Lactococcus starter cultures.[3][23][24] In the dairy industry today, quark is mostly produced with a small quantity of rennet, added after the culture when the solution is still only slightly acidic (ph 6.1).[21][3] The solution will then continue to acidify, allowed to reach an approximate pH of 4.6.[21][3] At this point, the acidity causes the casein proteins in the milk to begin precipitating.[25]

In Germany, it is continuously stirred to prevent hardening, resulting in a thick, creamy texture.[26] According to German regulations on cheese (Käseverordnung), "fresh cheeses" (Frischkäse) such as quark or cottage cheese must contain at least 73% water in the fat-free component.[19] German quark is usually sold in plastic tubs. This type of quark has the firmness of sour cream but is slightly drier, resulting in a somewhat crumbly texture (like ricotta).[26]

Basic quark contains about 0.2% fat; this basic quark or skimmed quark (Magerquark) must under German law have less than 10% fat by dry mass.[27][28] Quark with higher fat content is made by adding cream after cooling.[21][27] It has a smooth and creamy texture, and is slightly sweet (unlike sour cream). A firmer version called Schichtkäse (layer cheese) is often used for baking. Schichtkäse is distinguished from quark by having an added layer of cream sandwiched between two layers of quark.

Quark may be flavored with herbs, spices, or fruit.[26] In general, the dry mass of quark has 1% to 40% fat;[26] most of the rest is protein (80% of which is casein), calcium, and phosphate.

In the 19th century, there was no industrial production of quark (as end-product) and it was produced entirely for home use.[29] In the traditional home-made process, the milk would be allowed to let stand until it soured naturally by the presence of naturally occurring bacteria, although the hardening could be encouraged with the addition of some rennet.[20][29]

Some or most of the whey is removed to standardize the quark to the desired thickness. Traditionally, this is done by hanging the cheese in a muslin bag[21][30] or a loosely woven cotton gauze called cheesecloth and letting the whey drip off,[31] which gives quark its distinctive shape of a wedge with rounded edges. In industrial production, however, cheese is separated from whey in a centrifuge and later formed into blocks.[21]

Variations in quark preparation occur across different regions of Germany and Austria.[26]

Common uses

Various cuisines feature quark as an ingredient for appetizers, salads, main dishes, side dishes and desserts.

In Germany, quark is sold in cubic plastic tubs and usually comes in three different varieties, Magerquark (skimmed quark, <10% fat by dry mass.[27][28]), "regular" quark (20% fat in dry mass[lower-alpha 2]) and Sahnequark ("creamy quark", 40% fat in dry mass[lower-alpha 3]) with added cream. Similar gradations in fat content are also common in Eastern Europe.

While Magerquark is often used for baking or is eaten as breakfast with a side of fruit or muesli, Sahnequark also forms the basis of a large number of quark desserts (called Quarkspeise when homemade or Quarkdessert when sold in German[33]).

Much like yoghurts in some parts of the world, these foods mostly come with fruit flavoring (Früchtequark, fruit quark), sometimes with vanilla and are often also simply referred to as quark.

Dishes in Germanic-speaking areas

One common use for quark is in making cheesecake called Käsekuchen or Quarkkuchen in Germany.[34][35] Quark cheesecake is called Topfenkuchen in Austria. The Quarktorte in Switzerland may be equivalent, though this has also been described as a torte that combines quark and cream.[lower-alpha 4][11]

In neighboring Netherlands there is a different variant; these cakes, called kwarktaart in Dutch, usually have a cookie crumb crust, and the quark is typically mixed with whipped cream, gelatine, and sugar. These cakes do not require baking or frying, but instead are placed in the refrigerator to firm up.[36] They may be made with quark or with the yogurt-like quark that is common in the Netherlands (see above).[37]

In Austria, Topfen is commonly used in baking for desserts like above-mentioned Topfenkuchen, Topfenstrudel and Topfen-Palatschinken (Topfen-filled crèpes).

Quark is also often used as an ingredient for sandwiches, salads, and savory dishes. Quark, vegetable oil and wheat flour are the ingredients of a popular kind of baking powder leavened dough called Quarkölteig ("quark oil dough"), used in German cuisine as an alternative to yeast-leavened dough in home baking, since it is considerably easier to handle and requires no rising period. The resulting baked goods look and taste very similar to yeast-leavened goods, although they do not last as long and are thus usually consumed immediately after baking.

In Germany, quark mixed with chopped onions and herbs such as parsley and chives is called Kräuterquark. Kräuterquark is commonly eaten with boiled potatoes and has some similarity to tzatziki which is based on yoghurt.

Quark with linseed oil and potatoes is the national dish of the Sorbs in Lusatia and an iconic dish in Brandenburg and parts of Saxony. Quark also has been used among Ashkenazi Jews.[1]

Availability in other countries

Most of the Austrian and other Central and Eastern European varieties contain less whey and are therefore drier and more solid than the German and Scandinavian ones.

In the Netherlands, many products labelled "kwark" are not based on quark as described in this article (fresh acid-set cheese), but instead a thick yogurt-like product made using yogurt bacteria (such as Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus) in a quicker process using a centrifuge.[39][37]

Under Russian governmental regulations, tvorog is distinguished from cheeses, and classified as a separate type of dairy product.[40] Typical tvorog usually contain 65–80% water out of the total mass.[41]

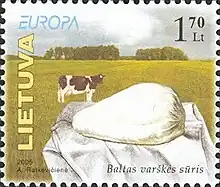

In several languages quark is also known as "white cheese" (French: fromage blanc, southern German: Weißkäse or weißer Käs, Hebrew: גבינה לבנה, romanized: gevina levana, Lithuanian: baltas sūris, Polish: biały ser, Serbian: beli sir), as opposed to any rennet-set "yellow cheese".[1] Another French name for it is fromage frais (fresh cheese), where the difference to fromage blanc is defined by French legislation: a product named fromage frais must contain live cultures when sold, whereas with fromage blanc fermentation has been halted.[42] In Swiss French, it is usually called séré.

In Israel, gevina levana denotes the creamy variety similar to the German types of quark.[1] The firmer version which was introduced to Israel during the Aliyah of the 1990s by immigrants from the former Soviet Union is differentiated as tvorog.

In Austria, the name Topfen (pot cheese) is common.[43] In Flanders, it is called plattekaas (runny cheese). In Finnish, it is known as rahka, while in Estonian as kohupiim (foamy milk), in Lithuanian as varškės sūris (curd cheese), in Ukrainian it is frequently called cир, and in Latvian is known as biezpiens (thick milk). Its Italian name is giuncata or cagliata (curd). Among the Albanians quark is known as gjizë.

It is traditional in the cuisines of Baltic, Germanic and Slavic-speaking countries as well as amongst Ashkenazi Jews and various Turkic peoples.

Dictionaries sometimes translate it as curd cheese, cottage cheese, farmer cheese or junket. In Germany, quark and cottage cheese are considered to be different types of fresh cheese and quark is often not considered cheese at all, while in Eastern Europe cottage cheese is usually viewed as a type of quark (e.g. Ukrainian for cottage cheese is "сир" syr).

Quark is similar to French fromage blanc. It is distinct from Italian ricotta because ricotta (Italian "recooked") is made from scalded whey. Quark is somewhat similar to yogurt cheeses such as the South Asian chak(k)a, the Arabic labneh, and the Central Asian suzma or kashk, but while these products are obtained by straining yogurt (milk fermented with thermophile bacteria), quark is made from soured milk fermented with mesophile bacteria.

Although common in continental Europe, manufacturing of quark is rare in the Americas. A few dairies manufacture it, such as the Vermont Creamery in Vermont,[44] and some specialty retailers carry it.[45][46][47] Lifeway Foods manufactures a product under the title "farmer cheese" which is available in a variety of metropolitan locations with Jewish, as well as former Soviet populations. Elli Quark, a Californian manufacturer of quark, offers soft quark in different flavors.[48]

In Canada, the firmer East European variety of quark is manufactured by Liberté Natural Foods; a softer German-style quark is manufactured in the Didsbury, Alberta, plant of Calgary-based Foothills Creamery. Glengarry Fine Cheesemaking in Lancaster (Eastern Ontario) also produces Quark. Also available in Canada is the very similar Dry Curd Cottage Cheese manufactured by Dairyland. Quark may also be available as baking cheese, pressed cottage cheese, or fromage frais.[49]

In Australia, Ukrainian traditional quark is produced by Blue Bay Cheese in the Mornington Peninsula. It is also sometimes available from supermarkets labelled as quark or quarg.

In New Zealand, European traditional Kwark is produced by Karikaas in North Canterbury. It is available in 350 g pots and available online and in speciality stores such as Moore Wilsons.

In the United Kingdom, fat-free quark is produced by several independent manufacturers based throughout the country. All the big four supermarkets in the UK sell their own branded quark, as well as other brands of quark.

In Finland, quark (rahka) is commonly available in supermarkets, both in plain and flavored forms. It is produced by Arla, Valio and is also sold under private labels by Kesko and S Group.[50] It is often used as a dessert when mixed with berries and whipped cream.[51] Karelians have a dish called piimäpiirakka, which is a quark pie.[52]

Slavic and Baltic countries

Desserts using quarks (Russian: tvorog, etc.) in Slavic regions include the tvarohovník in Slovakia, tvarožník in Czech Republic, sernik in Poland, and syrnyk in Ukraine) and cheese pancakes (syrnyky in Russia and Ukraine).

In Poland, twaróg is mixed with mashed potatoes to produce a filling for pierogi. Twaróg is also used to make gnocchi-shaped dumplings called leniwe pierogi ("lazy pierogi"). Ukrainian recipes for varenyky or lazy varenyky are similar but tvorog and mashed potatoes are different fillings which are usually not mixed together.

In Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, tvorog (Russian: творог) is highly popular and is bought frequently or made at home by almost every family. In Russian families, it is especially recommended for growing babies. It can be enjoyed simply with sour cream, or jam, sugar, sugar condensed milk, or as a breakfast food. It is often used as a stuffing in blinchiki offered at many fast-food restaurants. It is also commonly used as the base for making Easter cakes. It is mixed with eggs, sugar, raisins and nuts and dried into a solid pyramid-shaped mass called paskha. The mass can also be fried, then known as syrniki.

In Latvia, quark is eaten savory mixed with sour cream and scallions on rye bread or with potatoes. In desserts, quark is commonly baked into biezpiena plātsmaize, a crusted sheet cake baked with or without raisins. A sweetened treat biezpiena sieriņš (small curd cheese) is made of small sweetened blocks of quark dipped in chocolate.

- Dishes including quark

Russian paskha

Russian paskha

Noodle kugel with quark and raisins

Noodle kugel with quark and raisins

Pirog with quark and beet greens filling

Pirog with quark and beet greens filling

Quark rings (Pączki serowe)

Quark rings (Pączki serowe)

See also

Explanatory notes

- This group is distinguished from the "rennet cheeses", whose coagulation relies primarily on the action of rennet, in Fox's classification scheme (1993).[18]

- 20% FDM is also referred to as "half fat".[32]

- 40% FDM is also referred to as "full fat".[32]

- "Was in der deutschen Schweiz eine Quarktorte, ist in Deutschland eine Käsesahnetorte, denn Käsesahne ist eine süsse Creme aus Quark und Sahne."

References

Citations

- Marks, Gil (2010). "Gevina Levana". Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-39130-3.

- Tacitus: De origine et situ Germanorum (Germania) Archived 2012-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, par. 23.

- Guinee, Pudjya & Farkyhe (2012), p. 406.

- Kluge, Friedrich (1989). "Quark". Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. Walter de Gruyter. p. 574. ISBN 9783110845037. ISBN 3-11-084503-2 (in German)

- Adelung, Johann Christoph (1798). Der Quargkäse. p. 881.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Kluge, Friedrich (2002). "Quark". Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (24., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage (bearbeitet von Elmar Seebold) ed.). Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 605. ISBN 3-11-017473-1(in German)

- Pronk-Tiethoff, Saskia (2013). The Germanic loanwords in Proto-Slavic. Rodopi. p. 71. ISBN 9789401209847., citing Kluge & Seebold (2002) "Quark", Philippa, EWN (Etymlogisch woordenboek van het Nederlands) "kvark", Schuster-Sewc, HEW (Historisch-etymologisches Wörterbuch der ober- und niedersorbischen Sprache) 20:1563, etc.

- Wolfgang Pfeifer. Das Digitale Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (DWDS), Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Quark (in German)

- Johann Gottlieb Hauptmann. Niederlausitzsche Wendische Grammatica. Lübben, 1761. Twarog, p. 73 (in German).

- Imholtz, August A. Jr. (1977). "Charmed and Other Quarks". Verbatim. 3 (3): 148. ISBN 9783319148922.

- Schmid, Christian (2004). Durchs wilde Wortistan: unterwegs in der Welt der Wörter (in German). Cosmos-Verlag. p. 88. ISBN 9783305004065.

- Miklosich, Franz (1886). "tvarogŭ". Etymologisches wörterbuch der slavischen sprachen. Wien: W. Braumüller.

- Vasmer, Max (1973). Etimologicheskiy slovar' russkogo yazyka Этимологический словарь русского языка [Etymological dictionary of Russian language] (in Russian). Vol. 4. p. 31.; Vasmer, Max (1953-1958) Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Winter, Heidelberg. (in German)

- Shansky, N. M. (Н. М. Шанский); Bobrova, T. A. (Т. А. Боброва) (2004), Shkol'nyy etimologicheskiy slovar' russkogo yazyka. Proiskhozhdeniye slov Школьный этимологический словарь русского языка. Происхождение слов [Scholastic etymological dictionary of the Russian language. Origin of words], Moscow: Drofa Дрофа ISBN 5-7107-8679-9 (in Russian).

- Greek names for cheese.

- Johann Rädeln. Europäischer Sprach-Schatz – oder ... Wörterbuch ... in drei Theile verfasset. Leipzig, 1711. Quarg, Quark-Käs (in German)

- Christian Samuel Theodor Bernd. Die deutsche Sprache in dem Herzogthume Posen und einem Theile des angrenzenden Königreiches Polen. Bonn, 1820, p. 227, Der Qua(o)rk (in German).

- Fox, Patrick F (2004), "1. Cheese: An Overview", Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology (3rd ed.), Elsevier Academic Press, vol. 1: General Aspects, pp. 1–2, ISBN 978-0-08-050093-5. Also 2nd edition (1993), p. 22

- Käseverordung (German regulations on cheese; in German).

- Davis, John Gilbert (1965), Cheese: Manufacturing methods, American Elsevier, p. 756, ISBN 9780443010675

- Ranken, M. D. (2012). "Quarg". Food Industries Manual. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 94. ISBN 9781461520993. ISBN 978-1-4615-2099-3

- Fox, Patrick F; Guinee, Timothy P.; Cogan, Timothy M.; McSweeney, Paul L. H. (2000), "1. Cheese: An Overview", Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology (1st ed.), Aspen, vol. 1: General Aspects, pp. 379–380, ISBN 978-0-8342-1260-2

- Jelen, P.; A. Renz-Schauen (1989). "Quark manufacturing innovations and their effect on quality, nutritive value and consumer acceptance". Food Technology. 43 (3): 74.

- Shah, N.; P. Jelen (1991). "Lactose absorption by postweaning rats from Yoghurt, Quark, and Quark whey". Journal of Dairy Science. 74 (5): 1512–1520. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78311-2. PMID 1908866.

- Fox, Patrick F; Uniacke-Lowe, T.; McSweeney, Paul L. H.; O'Mahony, J. A. (2015), Dairy Chemistry and Biochemistry (2nd ed.), Springer, p. 148, ISBN 978-3-3191-4892-2

- "Guide to German Cheese and Dairy Products". Germanfoods.org. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Staff, M. C. (1998). 4 Cultured Milk and Fresh Cheeses. p. 148. ISBN 9780751403442.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Daweke, H.; Haase, J.; Irmsche, K. (2013), Diätkatalog: Diätspeisepläne, Indikation und klinische Grundlagen, Springer-Verlag, pp. 215, 225, ISBN 978-3-6429-6537-1

- Drusch & Einhorn-Stoll (2016), p. 24.

- Farkye, Nana Y.; Vedamuthu, Ebenezer R. (2005), Robinson, Richard K. (ed.), "Microbiology of Soft Cheeses", Dairy Microbiology Handbook: The Microbiology of Milk and Milk Products, John Wiley & Sons, p. 484, ISBN 978-0-4712-2756-4

- Fox, Patrick F; Guinee, Timothy P.; Cogan, Timothy M.; McSweeney, Paul L. H. (2017), Fundamentals of Cheese Science (2nd ed.), Springer, p. 571, ISBN 978-1-4899-7681-9

- Guinee, Pudjya & Farkyhe (2012), p. 407.

- Grell, Monika (1999). Unterrichtsrezepte. Beltz. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-407-22008-0.

- Weiss, Luisa (2016). Käsekuchen (Classic Quark Cheesecake); Quarkkuchen mit Mandarinen (Mandarin Orange Cheesecake). pp. 48–49, 52–53. ISBN 9781607748250.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Rönner, Josef (2006). Backen mit Trennkost. Schlütersche. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-3-89994-056-5.

- "The Dutch Table: Kwarktaart". Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Kwark". Keuringsdienst van Waarde. 15 February 2018. NPO 3. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Quark - Cheese.com". www.cheese.com. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- The Dutch Table: How to make quark

- ГОСТ Р 52096-2003. Творог. Технические условия. (Russian state standard GOST R 52096-2003. Tvorog. Specifications; in Russian). The standard for tvorog is defined separately from the standards for cheeses.

- Pokrovskiy, A. A. (А. А. Покровский); Samsonov, M. A. (М. А. Самсонов), eds. (1981). Spravochnik po diyetologii Справочник по диетологии [Dietology Handbook] (in Russian). Moscow: Medicina publishers.

- "Note d'information accompagnant le décret n°2007-628 relatif aux fromages et spécialités fromagères" (PDF). Ministère de l'économie. 2008.

- "Die besten Topfen Rezepte". IchKoche.at (in Austrian German).

- Quark (Vermont Butter & Cheese Creamery) Archived 2011-01-25 at the Wayback Machine, Culture.

- "Milton Creamery Quark available in Minnesota". Archived from the original on 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- "Appel Farms Traditional Quark (Green Label)". GermanDeli.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-20. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- "Cows' Milk Cheeses". Vermont Butter and Cheese Company Store. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- "Elli Quark". Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- "Baker's special". Western Creamery. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- "Kuluttaja: Proteiinirahkojen todellinen koostumus yllättää – katso vertailu". 29 October 2014.

- "Marjarahka". 20 July 2005.

- Nevavesi, Heli. Ortodoksisen paaston ja pääsiäisen ruokakulttuuri Raja-Karjalassa syntyneiden keskuudessa ja Valamon luostarissa. Savonia AMK 2004. http://portal.savonia.fi/img/amk/sisalto/_tki-ja-palvelut/julkaisutoiminta/pdf/Ortodoksisen_paaston_ja_paasiaisen_ruokakulttuuri_Raja_Karjalassa_koko-teos.pdf

General bibliography

- Drusch, S.; Einhorn-Stoll, U. (2016), "3. Quark: A Traditional German Fresh Cheese", Modernization of Traditional Food Processes and Products, Springer, pp. 21–30, ISBN 9781489976710 ISBN 978-1-4899-7671-0

- Guinee, T.; Pudjya, P. D.; Farkyhe, N. Y. (2012), "Fresh Acid-Cured Cheese Varieties", Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology (2nd ed.), Springer, vol. 2: Major Cheese Groups, pp. 363–420, ISBN 978-1-4615-2648-3.

External links

- Instruction on how to make Quark at home

- Recipe for homemade Quark without rennet

- Easter Molded Cheese Dessert Recipe - Paska / Paskha Archived 2017-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Konditoreja un deserti - recepšu kolekcijas, Receptes.lv Archived 2014-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Making Quark at home using buttermilk Archived 2017-03-06 at the Wayback Machine