Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem

Melisende (1105 – 11 September 1161) was Queen of Jerusalem from 1131 to 1153, and regent for her son between 1153 and 1161, while he was on campaign. She was the eldest daughter of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, and the Armenian princess Morphia of Melitene.

| Melisende | |

|---|---|

| |

| Queen of Jerusalem | |

| Reign | 1131–1153 |

| Predecessor | Baldwin II |

| Successor | Baldwin III (as sole monarch) |

| Co-Sovereign | Fulk (1131–1143) and Baldwin III (1143–1153) |

| Born | 1105 County of Edessa |

| Died | 11 September 1161 (aged 55–56) Jerusalem |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Fulk, King of Jerusalem |

| Issue | Baldwin III of Jerusalem Amalric I of Jerusalem |

| House | House of Rethel |

| Father | Baldwin II of Jerusalem |

| Mother | Morphia of Melitene |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Heir Patronage

Jerusalem had recently been conquered by Christian Franks in 1099 during the First Crusade, and Melisende's paternal family originally came from the County of Rethel in France. Her father Baldwin was a crusader knight who carved out the Crusader State of Edessa and married Morphia, daughter of the Armenian prince Gabriel of Melitene, in a diplomatic marriage to fortify alliances in the region.[1][2] Melisende, named after her paternal grandmother, Melisende of Montlhéry, grew up in Edessa until she was 13, when her father was elected as the King of Jerusalem as successor of his cousin Baldwin I. By the time of his election as king, Baldwin II and Morphia already had three daughters:[1] Melisende, Alice, and Hodierna. As the new king, Baldwin II had been encouraged to put away Morphia in favor of a new younger wife with better political connections, one that could yet bear him a male heir. Armenian historian Matthew of Edessa wrote that Baldwin II was thoroughly devoted to his wife,[1] and refused to consider divorcing her.[1] As a mark of his love for his wife, Baldwin II had postponed his coronation until Christmas Day 1119 so that Morphia and their daughters could travel to Jerusalem and so that the queen could be crowned alongside him.[1] For her part, Morphia did not interfere in the day to day politics of Jerusalem, but demonstrated her ability to take charge of affairs when events warranted it.[1] When Melisende's father was captured during a campaign in 1123, Morphia hired a band of Armenian mercenaries to discover where her husband was being held prisoner,[1] and in 1124 Morphia took a leading part in the negotiations with Baldwin's captors to have him released, including traveling to Syria and handing over their youngest daughter Ioveta as hostage and as surety for the payment of the king's ransom.[1] Both of her parents stood as role models for the young Melisende, half-Frankish and half-Armenian, growing up in the Frankish East in a state of constant warfare.

As the eldest child, Melisende was raised as heir presumptive.[1][2] Frankish women in the Outremer had a higher life expectancy than men, in part due to the constant state of war in the region, and as a result, Frankish women exerted a wide degree of influence in the region and provided a strong sense of continuity to Eastern Frankish society.[1] Women who inherited territory usually did so because men had died in war or violence. However, women, who were recognized as queen regnant, rarely exercised their authority directly. Instead their husband exercised authority through the rights of their wives, called jure uxoris.[1] Contemporaries of Melisende who did rule, however, included Urraca of Castile (1080–1129), and Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204). During her father's reign Melisende was styled daughter of the king and heir of the kingdom of Jerusalem, and took precedence above other nobles and Christian clergy in ceremonial occasions.[1][3] Increasingly she was associated with her father on official documents, including in the minting of money, granting of fiefdoms and other forms of patronage, and in diplomatic correspondence.[1] Baldwin raised his daughter as a capable successor to himself and Melisende enjoyed the support of the Haute Cour, a kind of royal council composed of the nobility and clergy of the realm.

However, Baldwin II also thought that he would have to marry Melisende to a powerful ally, one who would protect and safeguard Melisende's inheritance and her future heirs. Baldwin deferred to King Louis VI of France to recommend a Frankish vassal for his daughter's hand.[1][2][N 1] The Frankish connection remained an important consideration for Crusader Jerusalem, as the nascent kingdom depended heavily on manpower and connections from France, Germany, and Italy. By deferring to France, Baldwin II was not submitting Jerusalem to the suzerainty of France; rather, he was placing the moral guardianship of the Outremer with the West for its survival, reminding Louis VI that the Outremer was, to some extent, Frankish lands.[2]

Louis VI chose Fulk V, Count of Anjou and Main, a renownedly rich crusader and military commander, and to some extent a growing threat to Louis VI himself.[1] Fulk's son from a previous marriage, Geoffrey, was married to Empress Matilda, Henry I of England's designated heir as England's next queen regnant. Fulk V could be a potential grandfather to a future ruler of England, a relationship that would outflank Louis VI. Fulk's wealth, connections, and influence made him as powerful as the King of France, according to historian Zoe Oldenbourg.[2] Throughout the negotiations Fulk insisted on being sole ruler of Jerusalem. Hesitant, Baldwin II initially acquiesced to these demands though he would come to reconsider.[1][N 2] Baldwin II perceived that Fulk, an ambitious man with grown sons to spare, was also a threat to Baldwin II's family and interest, and specifically a threat to his daughter Melisende. Baldwin II suspected that once he had died, Fulk would repudiate Melisende and set her and her children aside in favor of Elias, Fulk's younger but full grown son from his first marriage as an heir to Jerusalem.[1]

Fulk and Melisende were married on 2 June 1129 in Jerusalem. When Melisende bore a son and heir in 1130, the future Baldwin III, her father took steps to ensure Melisende would rule after him as reigning Queen of Jerusalem. Baldwin II held a coronation ceremony investing the kingship of Jerusalem jointly between his daughter, his grandson Baldwin III, and Fulk. Strengthening her position, Baldwin II designated Melisende as sole guardian for the young Baldwin, excluding Fulk. When Baldwin II died the next year in 1131, Melisende and Fulk ascended to the throne as joint rulers. Later, William of Tyre wrote of Melisende's right to rule following the death of her father that "the rule of the kingdom remained in the power of the lady queen Melisende, a queen beloved by God, to whom it passed by hereditary right".[1][N 3] However, with the aid of his knights, Fulk excluded Melisende from granting titles, offering patronage, and of issuing grants, diplomas, and charters. Fulk openly and publicly dismissed her hereditary authority. The fears of Baldwin II seemed to be justified, and the continued mistreatment of their queen irritated the members of the Haute Cour, whose own positions would be eroded if Fulk continued to dominate the realm. Fulk's behavior was in keeping with his ruling philosophy, as in Anjou Fulk had squashed any attempts by local towns to administer themselves and strong-armed his vassals into submission.[2][5] Fulk's autocratic style contrasted with the somewhat collegial association with their monarch that native Eastern Franks had come to enjoy.

Palace intrigue

The estrangement between husband and wife was a convenient political tool that Fulk used in 1134 when he accused Hugh II of Jaffa of having an affair with Melisende. Hugh was the most powerful baron in the kingdom, and devotedly loyal to the memory of his cousin Baldwin II. This loyalty now extended to Melisende. Contemporary sources, such as William of Tyre, discount the alleged infidelity of Melisende and instead point out that Fulk overly favoured newly arrived Frankish crusaders from Anjou over the native nobility of the kingdom. Had Melisende been guilty, the Church and nobility likely would not have supported her later.[6]

Hugh allied himself with the Muslim city of Ascalon, and was able to hold off the army set against him. He could not maintain his position indefinitely, however. His alliance with Ascalon cost him support at court. The Patriarch negotiated lenient terms for peace, and Hugh was exiled for three years. Soon thereafter an unsuccessful assassination attempt against Hugh was attributed to Fulk or his supporters. This was reason enough for the queen's party to challenge Fulk openly, as Fulk's unfounded assertions of infidelity were a public affront that would severely damage Melisende's position.

Through what amounted to a palace coup, the queen's supporters overcame Fulk, and from 1135 onwards Fulk's influence rapidly deteriorated. One historian wrote that Fulk's supporters "went in terror of their lives" in the palace.[7] William of Tyre wrote that Fulk "did not attempt to take the initiative, even in trivial matters, without [Melisende's] knowledge". Husband and wife reconciled by 1136 and had a second son, Amalric. When Fulk was killed in a hunting accident in 1143, Melisende publicly and privately mourned for him.

Melisende's victory was complete. Again, she is seen in the historical record granting titles of nobility, fiefdoms, appointments and offices, granting royal favours and pardons and holding court. Melisende was no mere regent-queen for her son Baldwin III, but a queen regnant, reigning by right of hereditary and civil law.

Patroness of the church and arts

Melisende enjoyed the support of the Church throughout her lifetime; from her appointment as Baldwin II's successor, throughout the conflict with Fulk, and later when Baldwin III would come of age. In 1138 she founded the large convent of St. Lazarus in Bethany, where her younger sister Ioveta would rule as abbess. In keeping with a royal abbey, Melisende granted the convent the fertile plains of Jericho. Additionally, the queen supplied rich furnishings and liturgical vessels, so that it would not be inferior to religious houses for men. Melisende also gave endowments to the Holy Sepulchre, Our Lady of Josaphat, the Templum Domini, the Order of the Hospital, St Lazarus leper hospital, and the Praemonstratensian St Samuel's in Mountjoy.[8]

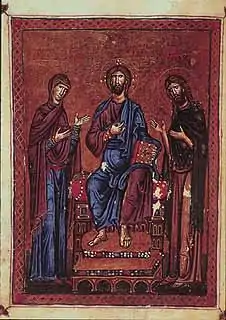

She also appreciated a variety of literary and visual arts due to the artistic exposures she received as a result of her parents' mixed Frankish-Armenian union. She created a school of bookmakers and a school of miniature painters of illuminated manuscripts.[9] She also commissioned the construction of a vaulted complex of shops, including the Street of Bad Cooking.[9] The street (Malquisinat, now the Sūq al-ʿAṭṭārīn/Spice Market)[10][11] was the central and most famous market of Crusader Jerusalem, where merchants and cooks supplied the numerous pilgrims who visited the city with food.[12]

Melisende's love for books and her religious piety were very well known. She was recognized as a patroness of books,[13] a fact her husband knew how to exploit following the incident that greatly injured their relationship and the monarchy's stability. King Fulk was jealous of the friendship Melisende shared with Hugh, Count of Jaffa.[14] Placed under scrutiny for supposed adultery with the queen, Hugh was attacked by an assassin who was most likely sent by the king himself.[15] This greatly angered the queen. Melisende was extremely hostile after the accusations about her alleged infidelity with Hugh and refused to speak to or allow in court those who sided with her husband – deeming them "under the displeasure of the queen".[16] Fulk likely set to appease his wife by commissioning her a book as a peace offering: the Melisende Psalter. It is expensively adorned, with a silk spine, ivory carvings, studded gemstones,[13][17] a calendar, and prayers with illuminated initial letters.[17] It is in Latin, suggesting that Melisende was literate in Latin and that some noblewomen in the Middle East were educated in this way. While there is no identification placing this book as Melisende's or made with her in mind, there are indications: the use of Latin text appropriate for a secular woman (as opposed to an abbess or such), the particular venerations of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalen (suggestive of the nearby abbey Melisende patronized), the only two royal mentions/inclusions being of Melisende's parents, and a possible bird pun on the king's name.[13][18]

Though influenced by Byzantine and Italian traditions in the illuminations, the artists who contributed to the Melisende Psalter had a unique and decidedly 'Jerusalem style'. The historian Hugo Buchtal wrote that

- "Jerusalem during the second quarter of the twelfth century possessed a flourishing and well-established scriptorium which could, without difficulty, undertake a commission for a royal manuscript de grand luxe".

There is no account of how Melisende received this gift but shortly after its creation, the royal union appeared stronger than ever. Two things prove the couple's reconciliation: 1) almost every single charter after this was issued by Fulk but labeled "with the consent and the approval of Queen Melisende", and 2) the birth of the royal pair's second son, Amalric, in 1136.[18] It is also reported that Queen Melisende mourned greatly after her husband fell off a horse and died in 1143.[9]

Second Crusade

In 1144 the Crusader state of Edessa was besieged in a border war that threatened its survival. Queen Melisende responded by sending an army led by constable Manasses of Hierges, Philip of Milly, and Elinand of Bures. Raymond of Antioch ignored the call for help, as his army was already occupied against the Byzantine Empire in Cilicia. Despite Melisende's army, Edessa fell.

Melisende sent word to the Pope in Rome, and the west called for a Second Crusade. The crusader expedition was led by French Louis VII of France and the German Emperor Conrad III. Accompanying Louis was his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, with her own vassal lords in tow. Eleanor had herself been designated by her father, William X, to succeed him in her own right, just as Melisende had been designated to succeed her father.

During the Crusader meeting in Acre in 1148, the battle strategy was planned. Conrad and Louis advised 18-year-old Baldwin III to attack the Muslim city-state of Damascus, though Melisende, Manasses, and Eleanor wanted to take Aleppo, which would aid them in retaking Edessa. The meeting ended with Damascus as their target. Damascus and Jerusalem were on very good diplomatic terms and there was a peace treaty between them. The result of this breach of treaty was that Damascus would never trust the Crusader states again, and the loss of a sympathetic Muslim state was a blow from which later monarchs of Jerusalem could not recover. After 11 months, Eleanor and Louis departed for France, ending the Second Crusade.

Mother and son

Melisende's relationship with her son was complex. As a mother she would know her son and his capabilities, and she is known to have been particularly close to her children. As a ruler she may have been reluctant to entrust decision-making powers to an untried youth. Either way there was no political or social pressure to grant Baldwin any authority before 1152, even though Baldwin reached majority in 1145. Baldwin III and Melisende were jointly crowned as co-rulers on Christmas Day, 1143. This joint crowning was similar to Melisende's own crowning with her father in 1128, and may have reflected a growing trend to crown one's heir in the present monarch's lifetime, as demonstrated in other realms of this period.

Baldwin grew up to be a capable, if not brilliant, military commander. By age 22 however, Baldwin felt he could take some responsibility in governance. Melisende had hitherto only partially associated Baldwin in her rule. Tension between mother and son mounted between 1150 and 1152, with Baldwin blaming Manasses for alienating his mother from him. The crisis reached a boiling point early 1152 when Baldwin demanded that the patriarch Fulcher crown him in the Holy Sepulchre, without Melisende present. The Patriarch refused. Baldwin, in protest, staged a procession in the city streets wearing laurel wreaths, a kind of self-crowning.

Baldwin and Melisende agreed to put the decision to the Haute Cour. The Haute Cour decided that Baldwin would rule the north of the kingdom and Melisende the richer Judea and Samaria, and Jerusalem itself. Melisende acquiesced, though with misgivings. This decision would prevent a civil war but also divide the kingdom's resources. Though later historians criticized Melisende for not abdicating in favor of her son, there was little impetus for her to do so. She was universally recognized as an exceptional steward for her kingdom, and her rule had been characterized as a wise one by church leaders and other contemporaries. Baldwin had not shown any interest in governance prior to 1152, and had resisted responsibility in this arena. The Church clearly supported Melisende, as did the barons of Judea and Samaria.

Despite putting the matter before the Haute Cour, Baldwin was not happy with the partition any more than Melisende. But instead of reaching further compromise, within weeks of the decision he launched an invasion of his mother's realms. Baldwin showed that he was Fulk's son by quickly taking the field; Nablus and Jerusalem fell swiftly. Melisende with her younger son Amalric and others sought refuge in the Tower of David. Church mediation between mother and son resulted in the grant of the city of Nablus and adjacent lands to Melisende to rule for life, and a solemn oath by Baldwin III not to disturb her peace. This peace settlement demonstrated that though Melisende lost the "civil war" to her son, she still maintained great influence and avoided total obscurity in a convent.

Retirement

By 1153, mother and son had been reconciled. Since the civil war, Baldwin had shown his mother great respect. Melisende's connections, especially to her sister Hodierna, and to her niece Constance of Antioch, meant that she had direct influence in northern Syria, a priceless connection since Baldwin had himself broken the treaty with Damascus in 1147.

As Baldwin III was often on military campaigns, he realized he had few reliable advisers. From 1154 onwards, Melisende is again associated with her son in many of his official public acts. In 1156, she concluded a treaty with the merchants of Pisa. In 1157, with Baldwin on campaign in Antioch, Melisende saw an opportunity to take el-Hablis, which controlled the lands of Gilead beyond the Jordan. Also in 1157, on the death of patriarch Fulcher, Melisende, her sister Ioveta the Abbess of Bethany, and Sibylla of Flanders had Amalric of Nesle appointed as patriarch of Jerusalem. Additionally, Melisende was witness to her son Amalric's marriage to Agnes of Courtenay in 1157. In 1160, she gave her assent to a grant made by her son Amalric to the Holy Sepulchre, perhaps on the occasion of the birth of her granddaughter Sibylla to Agnes and Amalric.

Death

In 1161, Melisende had what appears to have been a stroke. Her memory was severely impaired, and she could no longer take part in state affairs. Her sisters – the countess of Tripoli and abbess of Bethany – came to nurse her before she died on 11 September 1161. Melisende was buried next to her mother Morphia in the shrine of Our Lady of Josaphat. Melisende, like her mother, bequeathed property to the Orthodox monastery of Saint Sabbas in Jerusalem.

William of Tyre, writing on Melisende's 30-year reign, wrote that "she was a very wise woman, fully experienced in almost all affairs of state business, who completely triumphed over the handicap of her sex so that she could take charge of important affairs", and that, "striving to emulate the glory of the best princes, Melisende ruled the kingdom with such ability that she was rightly considered to have equalled her predecessors in that regard". Professor Bernard Hamilton of the University of Nottingham has written that, while William of Tyre's comments may seem rather patronizing to modern readers, they amount to a great show of respect from a society and culture in which women were regarded as having fewer rights and less authority than their brothers, their fathers or even their sons.

Notes

- Baldwin II's embassy to France was headed by his constable, William I of Bures and with Hugues de Payens.

- Historian Hans E. Mayer argued that Baldwin II had promised sole rulership of Jerusalem after his death to Fulk, however historian Bernard Hamilton points out that there is no evidence to support Mayer's conclusion that Baldwin ever intended to prevent Melisende from ruling, rather the opposite, that Baldwin II purposefully associated Melisende, and then Fulk, with his rule up until the time of his death.[4]

- reseditque reginam regni potestas penes dominam Melisendem, Deo amabilem reginam, cui jure hereditario competebat

- Hamilton, Bernard, Queens of Jerusalem, Ecclesiastical History Society, 1978, Frankish women in the Outremer, p. 143, Melisende's youth pp. 147, 148, Recognized as successor pp. 148, 149, Offers patronage and issues diplomas, Marriage with Fulk, Birth of Baldwin III, Second Crowing with father, husband, and son, p. 149,

- Oldenbourg, Zoe, The Crusades, Pantheon Books, 1966, Baldwin II searches for a husband for Melisende, feudal relationship between France and Jerusalem, Fulk V of Anjou, p. 264,

- ''filia regis et regni Jerosolimitani haeres

- Medieval Women; Queens of Jerusalem, p. 151

- Oldenbourg wrote that Fulk had "broken the resistance of his principal vassals on his own domains and paralyzed all attempts at emancipation by the townspeople. p. 264

- Bernard Hamilton (1978). Baker, Derek (ed.). Medieval Women. Oxford: The Ecclesiastical History Society. p. 150.

- Bernard Hamilton (1978). Baker, Derek (ed.). Medieval Women. Oxford: The Ecclesiastical History Society. p. 150.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2018). Crusaders, Cathars and the Holy Places. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-81278-1.

- Philips, Jonathan (2010). Holy Warriors: a Modern History of the Crusades. Vintage Books. p. 72.

- Anonymous Pilgrims, I–VIII. Translated by Stewart, Aubrey. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. 1897. p. 11.

- Boas, Adrian J. (2001). Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-58272-3.

Street of Bad Cooking/Street of Cooks (Malquisinat/Vicus Coquinatus/Vicus Coquinatorum/Kocatrice)

- "Jewish Food". The Jewish Mosaic. Hebrew School of Jerusalem. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- Philips, Jonathan (2010). Holy Warriors: a Modern History of the Crusades. Vintage Books. p. 70.

- Newman, Sharan (2014). Defending the City of God: a Medieval Queen, the First Crusades, and the Quest for Peace in Jerusalem. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 152.

- Newman, Sharan (2014). Defending the City of God: a Medieval Queen, the First Crusades, and the Quest for Peace in Jerusalem. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 155.

- Newman, Sharan (2014). Defending the City of God: a Medieval Queen, the First Crusades, and the Quest for Peace in Jerusalem. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 156.

- Tranovich, Margaret (2011). Melisende of Jerusalem: the World of a Forgotten Crusader Queen. Melisende. p. 23.

- Philips, Jonathan (2010). Holy Warriors: a Modern History of the Crusades. Vintage Books. p. 71.

Sources

- Bernard Hamilton (1978). Baker, Derek (ed.). Medieval Women. Oxford: The Ecclesiastical Historical Society. pp. 143–174. ISBN 0-631-12539-6.

- Hodgson, Natasha R. (2007). Women, Crusading and the Holy Land in Historical Narrative. Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-332-1.

- Hopkins, Andrea (2004). Damsels Not in Distress: the True Story of Women in Medieval Times. New York: Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 0-8239-3992-8.

- Mayer, Hans E. (1974). Studies in the History of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 26.

- Leon, Vicki (1997). Uppity Women of the Medieval Times. Berkeley, CA: Conari Books. ISBN 1-57324-010-9.

- Oldenbourg, Zoé (1965). The Crusades. New York: Pantheon Books, A Division of Random House. LCCN 65010013.

- Tranovich, Margaret, Melisende of Jerusalem: The World of a Forgotten Crusader Queen (Sawbridgeworth, East and West Publishing, 2011).

- Gaudette, Helen A. (2010), "The Spending Power of a Crusader Queen: Melisende of Jerusalem", in Theresa Earenfight (ed.), Women and Wealth in Late Medieval Europe, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 135–148

- Gerish, Deborah (2006), "Holy War, Royal Wives, and Equivocation in Twelfth-Century Jerusalem", in Naill Christie and Maya Yazigis (ed.), Noble Ideals and Bloody Realities, Leiden, J. Brill, pp. 119–144

- Gerish, Deborah (2012), "Royal Daughters of Jerusalem and the Demands of Holy War", Leidschrift Historisch Tijdschrift, vol. 27, no 3, pp. 89–112

- Hamilton, Bernard (1978), "Women in the Crusader States: the Queens of Jerusalem", in Derek Baker and Rosalind M. T. Hill (ed.), Medieval Women, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 143–174; Nurith Kenaan-Kedar, "Armenian Architecture in Twelfth-Century Crusader Jerusalem", Assaph Studies in Art History, no 3, pp. 77–91

- Kühnel, Bianca (1991), "The Kingly Statement of the Bookcovers of Queen Melisende’s Psalter", in Ernst Dassmann and Klaus Thraede (ed.), Tesserae: Festschrift für Joseph Engemann, Münster, Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, pp. 340–357

- Lambert, Sarah (1997), "Queen or Consort: Rulership and Politics in the Latin East, 1118–1228", in Anne J. Duggan (ed.), Queens and Queenship in Medieval Europe, Woodbridge, Boydell Press, pp. 153–169

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard (1972), "Studies in the History of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, vol. 26, pp. 93–182.[1]

- Newman, Sharan, Defending the City of God: a Medieval Queen, the First Crusades, and the Quest for Peace in Jerusalem, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014

- Philips, Jonathan. Holy Warriors: a Modern History of the Crusades, Vintage Books, 2010

- Ferdinandi, Sergio (2017). La Contea Franca di Edessa. Fondazione e Profilo Storico del Primo Principato Crociato nel Levante (1098–1150). Rome: Pontificia Università Antonianum. ISBN 978-88-7257-103-3.

Further reading

- Historical fiction

- Tarr, Judith (1997). Queen of Swords. Tom Doherty LLC.

External links

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard. “Studies in the History of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Volume 26 (1972), pp. 93–182.

.svg.png.webp)