RAF Akrotiri

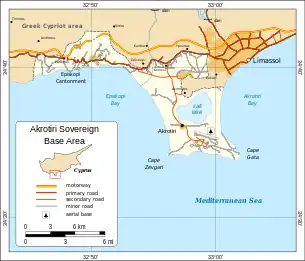

Royal Air Force Akrotiri, commonly abbreviated RAF Akrotiri (IATA: AKT, ICAO: LCRA) (Greek: Βασιλική Πολεμική Αεροπορία Ακρωτηρίου) is a large Royal Air Force (RAF) military airbase on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.[2] It is located in the Western Sovereign Base Area, one of two areas which comprise Akrotiri and Dhekelia, a British Overseas Territory, administered as a Sovereign Base Area.

RAF Akrotiri | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of British Forces Cyprus | |||||||

| Akrotiri in Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, Cyprus | |||||||

A RAF Tornado GR4 returns to RAF Akrotiri after a mission undertaken during Operation Shader | |||||||

| |||||||

RAF Akrotiri  RAF Akrotiri  RAF Akrotiri | |||||||

| Coordinates | 34°35′25″N 32°59′16″E | ||||||

| Type | Permanent joint operating base | ||||||

| Area | 2,128 hectares (5,260 acres) | ||||||

| Site information | |||||||

| Owner | Ministry of Defence | ||||||

| Operator | Royal Air Force | ||||||

| Condition | operational | ||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||

| Site history | |||||||

| Built | 1955 | ||||||

| In use | 1955 – present | ||||||

| Garrison information | |||||||

| Current commander | Group Captain Nikki Thomas | ||||||

| Occupants |

| ||||||

| Airfield information | |||||||

| Identifiers | IATA: AKT, ICAO: LCRA, WMO: 17601 | ||||||

| Elevation | 75.4 feet (23 metres) AMSL | ||||||

| |||||||

| Source: United Kingdom Military Aeronautical Information Publication[1] | |||||||

The station commander has a dual role, and is also the officer commanding the Akrotiri or Western Sovereign Base Area, reporting to the commander of British Forces Cyprus (BFC) who is also the Administrator.

History

RAF Akrotiri was first constructed in the mid-1950s to relieve pressure on the main RAF station in the centre of the island, RAF Nicosia.[3]

Suez Crisis

In late 1956, relations between the United Kingdom and Egypt had reached a crisis. The Suez Crisis saw a further increase in the strength of RAF forces in Cyprus. Akrotiri was mainly an airfield for fighter, photo reconnaissance, and ground attack aircraft. Its regular squadrons of Gloster Meteor night fighters, English Electric Canberra photo reconnaissance aircraft, and de Havilland Venom ground attack machines were reinforced by further Canberras which were ready for action if Egypt attacked Israel.[4]

1960s

After the Suez Crisis, the main emphasis of life on the airfield shifted to helping quell the EOKA revolt, and training missions. After the withdrawal from both Egypt and Iraq, and Suez Crisis, it was clear that a command centred on Cyprus could not control units stationed in the Arabian Peninsula, of which there were still many. Consequently, the Middle East Command was split; with that east of Suez being controlled from Aden, Yemen, and the remainder being renamed the Near East Command, controlled from Cyprus. From 1957 to 1969, four squadrons operating the Canberra (No. 6 Squadron, No. 32 Squadron, No. 73 Squadron, and No. 249 Squadron) provided first a conventional and then from November 1961, a nuclear striking capability as part of the Baghdad Pact, later the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO).[5]

Akrotiri, along with Nicosia, assumed a very important status, as virtually the sole means for projecting British airpower into the eastern Mediterranean, outside of aircraft carriers. In 1960, independence was granted to Cyprus, with the RAF maintaining both RAF Nicosia and RAF Akrotiri as airfields, controlled by the Near East Air Force (NEAF). However, Akrotiri assumed more importance as Nicosia was used for greater civil aviation traffic. After 1966, it was no longer possible to maintain RAF units at Nicosia due to pressures of space, and Akrotiri became the only RAF flying station left on the island.[6]

1970s

In August 1970, detachment 'G' of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) arrived at the airfield with Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft to monitor the Egypt / Israel Suez Canal fighting and cease fire. Permanent monitoring of Middle East Ceasefire was undertaken by the 100th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, known as Operation 'OLIVE HARVEST'.[7]

Up until 1974, RAF Akrotiri had a balanced force of aircraft assigned to it, including No. 9 Squadron and No. 35 Squadron, both flying Avro Vulcan strategic bombers. The Vulcans provided a bomber force for CENTO, one of the three main anti-Communist mutual defence pacts signed in the early days of the Cold War.[8] However, during that year, Turkish forces invaded Cyprus in connection with a Greek-sponsored coup. The UK then evacuated most of the RAF from Akrotiri as the CENTO treaty had degenerated to the point of uselessness. The two Vulcan squadrons left for UK stations in 1975. What was left at the airfield was the flying unit that is permanently assigned to the station to this day; No. 84 Squadron, a helicopter search and rescue unit.[9] In addition, the role of No. 34 Squadron RAF Regiment provided support.[10]

In September 1976, the US U-2 operations were reassigned to the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing (9th SRW), but the U-2 operation at RAF Akrotiri continued to be called Operating Location (OLIVE HARVEST) OH until September 1980. Thereafter, it became Detachment 3 of the 9th SRW, although the name OLIVE HARVEST continues. Two U-2s are stationed at RAF Akrotiri, and they are still monitoring the ceasefire agreement between the Egypt and Israel, although the present operations in the US Central Command area requires further missions. U-2s also transit through RAF Akrotiri either on going into the Central Command theatre, or returning to Beale AFB, California.[11]

1980s

Due to the station's relative proximity to the Middle East, it was used for the reception of American casualties after the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing.[13]

Between April 1983 and September 1984, RAF Boeing Chinooks helicopters deployed to Akrotiri in support of British United Nations forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL).[14]

In the mid-1980s, the US launched retaliatory attacks against Libya after the country's leader, Muammar al-Gaddafi, was implicated in the bombing of a West Berlin discotheque. Although the bombing operations were staged out of the UK, Akrotiri was employed in the role of an alternate in case of emergency, and was used as such by at least one aircraft. This led to retaliatory action against the British base.[15]

2000s - 2010s

In July 2006, RAF Akrotiri played a major role as a transit point for personnel evacuations out of Lebanon during the 2006 Lebanon War (see international reactions to the 2006 Lebanon War and Joint Task Force Lebanon).[16]

Akrotiri was the location of the main transmitter of the well known numbers station, the Lincolnshire Poacher, although transmissions ceased in 2008.[17]

In March 2011, the station was used as a staging base for support aircraft involved in Operation Ellamy, the UK's contribution to the NATO-led military intervention in Libya. Tanker support and logistical units were based here to support aerial operations over the country.[18]

In August 2013, six RAF Eurofighter Typhoon aircraft were deployed to Akrotiri to defend the base, "to ensure the protection of UK interests and the defence of our sovereign base areas at a time of heightened tension in the wider region". Earlier, two RAF TriStar aerial refuelling aircraft and a Sentry AEW1 had been deployed to Akrotiri.[19][20]

The station hosted the main hospital for British Forces Cyprus, The Princess Mary's Hospital (TPMH), located on Cape Zevgari. This closed in October 2012, and cases too serious to be dealt with at the base health clinic are sent to the private Ygia Polyclinic in Limassol.[1][21]

In August 2014, six RAF Panavia Tornado fighter-bombers were deployed to Akrotiri to carry out reconnaissance missions over Iraq, following the rise of Islamic State (ISIS) in Iraq and Syria. On 26 September 2014, Members of Parliament voted in favour of the RAF carrying out air strikes on ISIS in Iraq, and on 27 September the first two Tornado jets took off from Akrotiri loaded with laser-guided bombs and missiles. On 30 September 2014, two British Tornados successfully intercepted and attacked ISIS targets of a heavily armed truck, at the request of Iraqi Kurdish fighters.[22][23]

The station was used to support the 2018 missile strikes against Syria.[24]

In June 2019, the station launched the RAF's first F-35 Lightning II operational sortie. Six aircraft were deployed to take part in operations against Islamic State.[25]

Controversy

Radar

In 2007, a large over-the-horizon radar antenna was erected within the base. Several demonstrations and protests took place, with the most memorable incident being the act of MP (MEP since 2004) Marios Matsakis chaining himself to the antenna. Matsakis stated "It is outrageous that in the 21st century there are Cypriot villages living under British military rule, neither under their own government's jurisdiction nor under the protection of the EU treaties".[26]

US surveillance flights

In 2010, U-2s from the United States Air Force's 9th Reconnaissance Wing were used in Operation Cedar Sweep to fly surveillance over Lebanon, relaying information about Hezbollah militants to Lebanese authorities, and in Operation Highland Warrior to fly surveillance over Turkey and northern Iraq to relay information to Turkish authorities. These flights were the topic of acrimonious diplomatic cables between British officials and the American embassy, later leaked by WikiLeaks, with David Miliband saying that "policymakers needed to get control of the military". The British were concerned that the flights over Lebanon were authorised by the Lebanese Ministry of Defence, rather than the entire cabinet, and that the intelligence so gained could lead to the UK being complicit in the unlawful torture of detainees. After warnings that these issues "could jeopardise future use of British territory", John Rood, a senior Bush administration official, and Mariot Leslie, the Foreign Office's director general for defence and intelligence, became involved. Leslie said that the U.S. was not actually expected to check on detained terrorists, but that future spy missions would require full written applications.[27][28]

Based units

Units based at RAF Akrotiri.[29][30]

Royal Air Force

No. 2 Group (Air Combat Support) RAF

No 83. Expeditionary Air Group RAF

- No. 903 Expeditionary Air Wing

- Operation Shader (anti-ISIL operations)

- Detachment of nine Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4 from RAF Coningsby[32] and RAF Lossiemouth

- Elements of the RAF Air Mobility Force:

- Airbus A400M Atlas transport aircraft (replaced previously operated Hercules C5 aircraft withdrawn from RAF service in 2023)

- Voyager KC3 tanker aircraft[32]

- Elements of the RAF ISTAR Force:

- MQ-9A Reaper UAVs (No. 13 Squadron RAF) and RC-135W Rivet Joint (No. 51 Squadron RAF) (aircraft may operate from locations other than RAF Akrotiri)[33][34]

- Shadow R1 aircraft from No. 14 Squadron RAF[35]

- P-8 Poseidon aircraft from RAF Lossiemouth (deployed in October 2023 in conjunction with the Royal Navy's Littoral Response Group (South) in response to the outbreak of the 2023 Israel–Hamas war).[36]

- Elements of the RAF A4 Force

- Operation Shader (anti-ISIL operations)

- RAF Akrotiri Volunteer Band

Joint service units

- Cyprus Operations Support Unit

United States Air Force

- 9th Reconnaissance Wing

- 9th Operations Group (Detachment 1) – Lockheed U-2S

Airlines and destinations

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| AirTanker | Charter: RAF Brize Norton Seasonal charter: Birmingham, East Midlands |

| West Atlantic UK | Charter: Bari, Ta'if, Warton[37] |

See also

References

Citations

- "United Kingdom Military Aeronautical Information Publication AD 2 - LCRA – Akrotiri" (PDF). AIDU.MoD.uk. Ministry of Defence. 11 August 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- "RAF Akrotiri - The Station". Royal Air Force. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- "Journal 30" (PDF). RAFMuseum.org.uk. Royal Air Force Historical Society. 2007. p. 9. ISSN 1361-4231. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Varble, Derek (2003). The Suez Crisis. Osprey. p. 51. ISBN 978-1841764184.

- Lee, 1989, 172-176.

- Proctor, Ian (2014). The Royal Air Force in the Cold War 1950-1970. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1783831890.

- "RAF Akrotiri". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 174. UK Parliament: House of Commons. 15 June 1990. col. 380W. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Lee, Sir David (1989). Wings in the Sun: A History of the Royal Air Force in the Mediterranean 1945-1986. Great Britain: RAF Air Historical Branch, HMSO Books.

- "84 Squadron". RAF.MoD.uk. Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 1 September 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Pike, Mike (19 October 2018). "Gunners target Daesh terror with Cyprus Return". RAF News. No. 1, 453. p. 13. ISSN 0035-8614.

- "UK overruled on Lebanon spy flights from Cyprus, WikiLeaks cables reveal". TheGuardian.com. The Guardian. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- March 1989, p. 88.

- "Report of the DoD Commission on Beirut Int'l Airport terrorist act, October 23, 1983 – part eight". Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Cotter 2008, p. 71.

- "British base on Cyprus attacked: two wounded". NYTimes.com. New York Times. 5 August 1986. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "News in English". HRI.org. Cyprus News Agency. 6 July 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Mason, Simon (30 October 2009). "E3 Lincolnshire Poacher". Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Second UK strike against Libyan defence assets". MoD.uk. Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Rankin, Ben (29 August 2013). "Syria: RAF Typhoon jets sent to Cyprus". Mirror.co.uk. Daily Mirror. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Typhoons deploying to Cyprus". GOV.UK. HM Government. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Vassallo, David (2017). A history of the Princess Mary Hospital; Royal Air Force Akrotiri 1963-2013. Vassallo. p. 22. ISBN 9780992798017.

- "RAF planes bomb Islamic State targets in Iraq for the first time". TheGuardian.com. The Guardian. 30 September 2014.

- "RAF jets sent on Iraqi combat mission". BBC.co.uk. BBC News.

- "Syria air strikes: UK confident strikes were successful, says PM". BBC.co.uk. BBC News. 14 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "UK stealth fighter jets join fight against Islamic State". BBC.co.uk. BBC News. 25 June 2019.

- "MEP arrested at UK base in Cyprus". News.BBC.co.uk. BBC News. 12 April 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Norton-Taylor, Richard; Leigh, David (1 December 2010). "UK overruled on Lebanon spy flights from Cyprus, WikiLeaks cables reveal". TheGuardian.com. The Guardian.

- "Viewing cable 08LONDON1350, HMG RAISES THE BAR ON INTEL FLIGHTS". WikiLeaks. 2 December 2010. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010.

- "RAF Akrotiri". RAF.MoD.uk. Royal Air Force. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "U-2S/TU-2S 'Dragon Lady'". United States Air Force Air Power Yearbook 2021. Key Publishing: 113. 2021.

- "RAF Akrotiri helicopter capability transfers from Griffin to Puma". RAF.MoD.uk. Royal Air Force. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- Air Forces Monthly. Stamford, Lincolnshire, England: Key Publishing Ltd. January 2016. p. 4.

- "UK deploys Reaper to the Middle East". GOV.UK. HM Government. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- "RAF Rivet Joint on first operational deployment over Iraq". FlightGlobal.com. Flight Global. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- "RAF Shadow R1". Milavreachout.org. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- Sheridan, Danielle (12 October 2023). "Royal Navy to send ships and aircraft to support Israel".

- "BAE102 flight activity history". uk.FlightAware.com. Flight Aware. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

Bibliography

- Cotter, J. (2008). Royal Air Force celebrating 90 years. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-946219-11-7.

- Lee, David (1989). Wings in the Sun: A history of the Royal Air Force in the Mediterranean 1945–1986. HMSO Books.

- March, P. (1989). Royal Air Force Yearbook 1989. Fairford, UK: Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund.