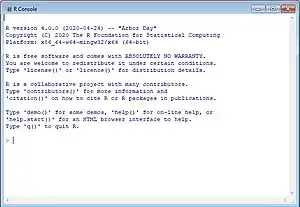

R (programming language)

R is a programming language for statistical computing and graphics supported by the R Core Team and the R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Created by statisticians Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman, R is used among data miners, bioinformaticians and statisticians for data analysis and developing statistical software.[7] The core R language is augmented by a large number of extension packages containing reusable code and documentation.

| |

R terminal | |

| Paradigms | Multi-paradigm: procedural, object-oriented, functional, reflective, imperative, array[1] |

|---|---|

| Designed by | Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman |

| Developer | R Core Team |

| First appeared | August 1993 |

| Stable release | |

| Typing discipline | Dynamic |

| Platform | arm64 and x86-64 |

| License | GNU GPL v2 |

| Filename extensions | |

| Website | www |

| Influenced by | |

| Influenced | |

| Julia[6] | |

| |

According to user surveys and studies of scholarly literature databases, R is one of the most commonly used programming languages in data mining.[8] As of April 2023, R ranks 16th in the TIOBE index, a measure of programming language popularity, in which the language peaked in 8th place in August 2020.[9][10]

The official R software environment is an open-source free software environment released as part of the GNU Project and available under the GNU General Public License. It is written primarily in C, Fortran, and R itself (partially self-hosting). Precompiled executables are provided for various operating systems. R has a command line interface.[11] Multiple third-party graphical user interfaces are also available, such as RStudio, an integrated development environment, and Jupyter, a notebook interface.

History

.jpg.webp)

R was started by professors Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman as a programming language to teach introductory statistics at the University of Auckland.[12] The language took heavy inspiration from the S programming language with most S programs able to run unaltered in R[5] as well as from Scheme's lexical scoping allowing for local variables.[1] The name of the language comes from being an S language successor and the shared first letter of the authors, Ross and Robert.[13] Ihaka and Gentleman first shared binaries of R on the data archive StatLib and the s-news mailing list in August 1993.[14] In June 1995, statistician Martin Mächler convinced Ihaka and Gentleman to make R free and open-source under the GNU General Public License.[14][15] Mailing lists for the R project began on 1 April 1997 preceding the release of version 0.50.[16] R officially became a GNU project on 5 December 1997 when version 0.60 released.[17] The first official 1.0 version was released on 29 February 2000.[12]

The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) was founded in 1997 by Kurt Hornik and Fritz Leisch to host R's source code, executable files, documentation, and user-created packages.[18] Its name and scope mimics the Comprehensive TeX Archive Network and the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network.[18] CRAN originally had three mirrors and 12 contributed packages.[19] As of December 2022, it has 103 mirrors[20] and 18,976 contributed packages.[21]

The R Core Team was formed in 1997 to further develop the language.[22][23] As of January 2022, it consists of Chambers, Gentleman, Ihaka, and Mächler, plus statisticians Douglas Bates, Peter Dalgaard, Kurt Hornik, Michael Lawrence, Friedrich Leisch, Uwe Ligges, Thomas Lumley, Sebastian Meyer, Paul Murrell, Martyn Plummer, Brian Ripley, Deepayan Sarkar, Duncan Temple Lang, Luke Tierney, and Simon Urbanek, as well as computer scientist Tomas Kalibera. Stefano Iacus, Guido Masarotto, Heiner Schwarte, Seth Falcon, Martin Morgan, and Duncan Murdoch were members.[14][24] In April 2003,[25] the R Foundation was founded as a non-profit organization to provide further support for the R project.[26]

Features

Data processing

R's data structures include vectors, arrays, lists, data frames and environments.[27] Vectors are ordered collections of values and can be mapped to arrays of one or more dimensions in a column major order. That is, given an ordered collection of dimensions, one fills in values along the first dimension first, then fills in one-dimensional arrays across the second dimension, and so on.[28] R supports array arithmetics and in this regard is like languages such as APL and MATLAB.[27][29] The special case of an array with two dimensions is called a matrix. Lists serve as collections of objects that do not necessarily have the same data type. Data frames contain a list of vectors of the same length, plus a unique set of row names.[27] R has no scalar data type.[30] Instead, a scalar is represented as a length-one vector.[31]

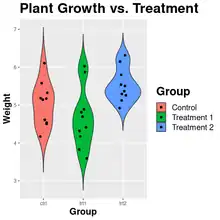

R and its libraries implement various statistical techniques, including linear, generalized linear and nonlinear modeling, classical statistical tests, spatial and time-series analysis, classification, clustering, and others. For computationally intensive tasks, C, C++, and Fortran code can be linked and called at run time. Another of R's strengths is static graphics; it can produce publication-quality graphs that include mathematical symbols.[32]

Programming

R is an interpreted language; users can access it through a command-line interpreter. If a user types 2+2 at the R command prompt and presses enter, the computer replies with 4.

R supports procedural programming with functions and, for some functions, object-oriented programming with generic functions.[33] Due to its S heritage, R has stronger object-oriented programming facilities than most statistical computing languages. Extending it is facilitated by its lexical scoping rules, which are derived from Scheme.[34] R uses S syntax (not to be confused with S-expressions) to represent both data and code.[35] R's extensible object system includes objects for (among others): regression models, time-series and geo-spatial coordinates. Advanced users can write C, C++,[36] Java,[37] .NET[38] or Python code to manipulate R objects directly.[39]

Functions are first-class objects and can be manipulated in the same way as data objects, facilitating meta-programming that allows multiple dispatch. Function arguments are passed by value, and are lazy—that is to say, they are only evaluated when they are used, not when the function is called.[40] A generic function acts differently depending on the classes of the arguments passed to it. In other words, the generic function dispatches the method implementation specific to that object's class. For example, R has a generic print function that can print almost every class of object in R with print(objectname).[41] R is highly extensible through the use of packages for specific functions and specific applications.

Packages

R's capabilities are extended through user-created[42] packages, which offer statistical techniques, graphical devices, import/export, reporting (RMarkdown, knitr, Sweave), etc. These packages and their easy installation and use has been cited as driving the language's widespread adoption in data science.[43][44][45][46][47] The packaging system is also used by researchers to organize research data, code, and report files in a systematic way for sharing and archiving.[48]

Multiple packages are included with the basic installation. Additional packages are available on CRAN,[21] Bioconductor, R-Forge,[49] Omegahat,[50] GitHub, and other repositories.[51][52][53]

The "Task Views" on the CRAN website[54] lists packages in fields including Finance, Genetics, High-Performance Computing, Machine Learning, Medical Imaging, Meta-Analysis,[55] Social Sciences and Spatial Statistics.[55] R has been identified by the FDA as suitable for interpreting data from clinical research.[56] Microsoft maintains a daily snapshot of CRAN that dates back to Sept. 17, 2014.[57]

Other R package resources include R-Forge,[58][49] a platform for the collaborative development of R packages. The Bioconductor project provides packages for genomic data analysis, including object-oriented data handling and analysis tools for data from Affymetrix, cDNA microarray, and next-generation high-throughput sequencing methods.[59]

A group of packages called the Tidyverse, which can be considered a "dialect" of the R language, is increasingly popular among developers.[note 1] It strives to provide a cohesive collection of functions to deal with common data science tasks, including data import, cleaning, transformation, and visualisation (notably with the ggplot2 package). Dynamic and interactive graphics are available through additional packages.[60]

Interfaces

Early developers preferred to run R via the command line console,[61] succeeded by those who prefer an IDE.[62] IDEs for R include (in alphabetical order) R.app (OSX/macOS only), Rattle GUI, R Commander, RKWard, RStudio, and Tinn-R.[61] R is also supported in multi-purpose IDEs such as Eclipse via the StatET plugin,[63] and Visual Studio via the R Tools for Visual Studio.[64] Of these, RStudio is the most commonly used.[62]

Statistical frameworks which use R in the background include Jamovi and JASP.

Editors that support R include Emacs, Vim (Nvim-R plugin),[65] Kate,[66] LyX,[67] Notepad++,[68] Visual Studio Code, WinEdt,[69] and Tinn-R.[70] Jupyter Notebook can also be configured to edit and run R code.[71]

R functionality is accessible from scripting languages including Python,[72] Perl,[73] Ruby,[74] F#,[75] and Julia.[76] Interfaces to other, high-level programming languages, like Java[77] and .NET C#[78][79] are available.

Implementations

The main R implementation is written in R, C, and Fortran.[80] Several other implementations are aimed at improving speed or increasing extensibility. A closely related implementation is pqR (pretty quick R) by Radford M. Neal with improved memory management and support for automatic multithreading. Renjin and FastR are Java implementations of R for use in a Java Virtual Machine. CXXR, rho, and Riposte[81] are implementations of R in C++. Renjin, Riposte, and pqR attempt to improve performance by using multiple cores and deferred evaluation.[82] Most of these alternative implementations are experimental and incomplete, with relatively few users, compared to the main implementation maintained by the R Development Core Team.

TIBCO, who previous sold the commercial implementation S-PLUS, built a runtime engine called TERR, which is part of Spotfire.[83]

Microsoft R Open (MRO) is a fully compatible R distribution with modifications for multi-threaded computations.[84][85] As of 30 June 2021, Microsoft started to phase out MRO in favor of the CRAN distribution.[86]

Community

The R community hosts many conferences and in-person meetups. Some of these groups include:

- R-Ladies: an organization to promote gender diversity in the R community[87]

- UseR!: an annual international R user conference[88]

- SatRdays: R-focused conferences held on Saturdays[89]

- R Conference[90]

- Posit::conf (formerly known as Rstudio::conf)[91]

The R Foundation supports two conferences, useR! and Directions in Statistical Computing (DSC), and endorses several others like R@IIRSA, ConectaR, LatinR, and R Day.[88]

The R Journal

The R Journal is an open access, refereed journal of the R project. It features short to medium-length articles on the use and development of R, including packages, programming tips, CRAN news, and foundation news.

Comparison with alternatives

SAS

In January 2009, the New York Times ran an article charting the growth of R, noting its extensibility with user-created packages as well as R's open-source nature in contrast to SAS.[92] SAS supports Windows, UNIX, and z/OS.[93] R has precompiled binaries for Windows, macOS, and Linux with the option to compile and install R from source code.[94] SAS can only store data in rectangular data sets while R's more versatile data structures allow it to perform difficult analysis more flexibly. Completely integrating functions in SAS requires a developer's kit but, in R, user-defined functions are already on equal footing with provided functions.[95] In a technical report authored by Patrick Burns in 2007, respondents found R more convenient for periodic reports but preferred SAS for big data problems.[96]

Stata

Stata and R are designed to be easily extendable. Outputs in both software are structured to become inputs for further analysis. They hold data in main memory giving a performance boost but limiting data both can handle. R is free software while Stata is not.[97]

Python

Python and R are interpreted, dynamically typed programming languages with duck typing that can be extended by importing packages. Python is a general-purpose programming language while R is specifically designed for doing statistical analysis. Python has a BSD-like license in contrast to R's GNU General Public License but still permits modifying language implementation and tools.[98]

Commercial support

Although R is an open-source project, some companies provide commercial support and extensions.

In 2007, Richard Schultz, Martin Schultz, Steve Weston, and Kirk Mettler founded Revolution Analytics to provide commercial support for Revolution R, their distribution of R, which includes components developed by the company. Major additional components include ParallelR, the R Productivity Environment IDE, RevoScaleR (for big data analysis), RevoDeployR, web services framework, and the ability for reading and writing data in the SAS file format.[99] Revolution Analytics offers an R distribution designed to comply with established IQ/OQ/PQ criteria that enables clients in the pharmaceutical sector to validate their installation of REvolution R.[100] In 2015, Microsoft Corporation acquired Revolution Analytics[101] and integrated the R programming language into SQL Server, Power BI, Azure SQL Managed Instance, Azure Cortana Intelligence, Microsoft ML Server and Visual Studio 2017.[102]

In October 2011, Oracle announced the Big Data Appliance, which integrates R, Apache Hadoop, Oracle Linux, and a NoSQL database with Exadata hardware.[103] As of 2012, Oracle R Enterprise[104] became one of two components of the "Oracle Advanced Analytics Option"[105] (alongside Oracle Data Mining).

IBM offers support for in-Hadoop execution of R,[106] and provides a programming model for massively parallel in-database analytics in R.[107]

TIBCO offers a runtime-version R as a part of Spotfire.[108]

Mango Solutions offers a validation package for R, ValidR,[109][110] to comply with drug approval agencies, such as the FDA. These agencies required the use of validated software, as attested by the vendor or sponsor.[111]

Examples

Basic syntax

The following examples illustrate the basic syntax of the language and use of the command-line interface. (An expanded list of standard language features can be found in the R manual, "An Introduction to R".[112])

In R, the generally preferred assignment operator is an arrow made from two characters <-, although = can be used in some cases.[113][114]

> x <- 1:6 # Create a numeric vector in the current environment

> y <- x^2 # Create vector based on the values in x.

> print(y) # Print the vector’s contents.

[1] 1 4 9 16 25 36

> z <- x + y # Create a new vector that is the sum of x and y

> z # Return the contents of z to the current environment.

[1] 2 6 12 20 30 42

> z_matrix <- matrix(z, nrow=3) # Create a new matrix that turns the vector z into a 3x2 matrix object

> z_matrix

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 2 20

[2,] 6 30

[3,] 12 42

> 2*t(z_matrix)-2 # Transpose the matrix, multiply every element by 2, subtract 2 from each element in the matrix, and return the results to the terminal.

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 2 10 22

[2,] 38 58 82

> new_df <- data.frame(t(z_matrix), row.names=c('A','B')) # Create a new data.frame object that contains the data from a transposed z_matrix, with row names 'A' and 'B'

> names(new_df) <- c('X','Y','Z') # Set the column names of new_df as X, Y, and Z.

> print(new_df) # Print the current results.

X Y Z

A 2 6 12

B 20 30 42

> new_df$Z # Output the Z column

[1] 12 42

> new_df$Z==new_df['Z'] && new_df[3]==new_df$Z # The data.frame column Z can be accessed using $Z, ['Z'], or [3] syntax and the values are the same.

[1] TRUE

> attributes(new_df) # Print attributes information about the new_df object

$names

[1] "X" "Y" "Z"

$row.names

[1] "A" "B"

$class

[1] "data.frame"

> attributes(new_df)$row.names <- c('one','two') # Access and then change the row.names attribute; can also be done using rownames()

> new_df

X Y Z

one 2 6 12

two 20 30 42

Structure of a function

One of R's strengths is the ease of creating new functions. Objects in the function body remain local to the function, and any data type may be returned.[115] Example:

# Declare function “f” with parameters “x”, “y“

# that returns a linear combination of x and y.

f <- function(x, y) {

z <- 3 * x + 4 * y

return(z) ## the return() function is optional here

}

> f(1, 2)

[1] 11

> f(c(1,2,3), c(5,3,4))

[1] 23 18 25

> f(1:3, 4)

[1] 19 22 25

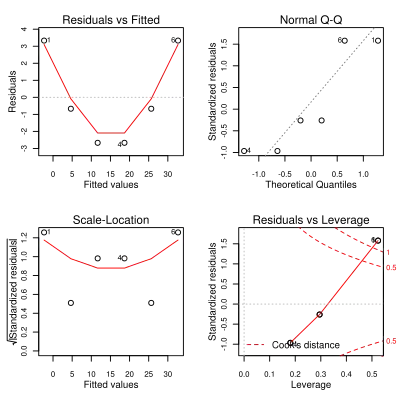

Modeling and plotting

The R language has built-in support for data modeling and graphics. The following example shows how R can easily generate and plot a linear model with residuals.

> x <- 1:6 # Create x and y values

> y <- x^2

> model <- lm(y ~ x) # Linear regression model y = A + B * x.

> summary(model) # Display an in-depth summary of the model.

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x)

Residuals:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

3.3333 -0.6667 -2.6667 -2.6667 -0.6667 3.3333

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -9.3333 2.8441 -3.282 0.030453 *

x 7.0000 0.7303 9.585 0.000662 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 3.055 on 4 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9583, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9478

F-statistic: 91.88 on 1 and 4 DF, p-value: 0.000662

> par(mfrow = c(2, 2)) # Create a 2 by 2 layout for figures.

> plot(model) # Output diagnostic plots of the model.

Mandelbrot set

Short R code calculating Mandelbrot set through the first 20 iterations of equation z = z2 + c plotted for different complex constants c. This example demonstrates:

- use of community-developed external libraries (called packages), such as the caTools package

- handling of complex numbers

- multidimensional arrays of numbers used as basic data type, see variables

C,Z, andX.

install.packages("caTools") # install external package

library(caTools) # external package providing write.gif function

jet.colors <- colorRampPalette(c("green", "pink", "#007FFF", "cyan", "#7FFF7F",

"white", "#FF7F00", "red", "#7F0000"))

dx <- 1500 # define width

dy <- 1400 # define height

C <- complex(real = rep(seq(-2.2, 1.0, length.out = dx), each = dy),

imag = rep(seq(-1.2, 1.2, length.out = dy), dx))

C <- matrix(C, dy, dx) # reshape as square matrix of complex numbers

Z <- 0 # initialize Z to zero

X <- array(0, c(dy, dx, 20)) # initialize output 3D array

for (k in 1:20) { # loop with 20 iterations

Z <- Z^2 + C # the central difference equation

X[, , k] <- exp(-abs(Z)) # capture results

}

write.gif(X, "Mandelbrot.gif", col = jet.colors, delay = 100)

See also

Notes

- As of 13 June 2020, Metacran listed 7 of the 8 core packages of the Tidyverse in the list of most download R packages.

References

- Morandat, Frances; Hill, Brandon; Osvald, Leo; Vitek, Jan (11 June 2012). "Evaluating the design of the R language: objects and functions for data analysis". European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming. 2012: 104–131. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31057-7_6. Retrieved 17 May 2016 – via SpringerLink.

- Peter Dalgaard (16 June 2023). "R 4.3.1 is released". Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- "R scripts". mercury.webster.edu. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- "R Data Format Family (.rdata, .rda)". Loc.gov. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Hornik, Kurt; The R Core Team (12 April 2022). "R FAQ". The Comprehensive R Archive Network. 3.3 What are the differences between R and S?. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- "Introduction". The Julia Manual. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Giorgi, Federico M.; Ceraolo, Carmine; Mercatelli, Daniele (27 April 2022). "The R Language: An Engine for Bioinformatics and Data Science". Life. 12 (5): 648. Bibcode:2022Life...12..648G. doi:10.3390/life12050648. ISSN 2075-1729. PMC 9148156. PMID 35629316.

- R's popularity

- David Smith (2012); R Tops Data Mining Software Poll, R-bloggers, 31 May 2012.

- Karl Rexer, Heather Allen, & Paul Gearan (2011); 2011 Data Miner Survey Summary, presented at Predictive Analytics World, Oct. 2011.

- Robert A. Muenchen (2012). "The Popularity of Data Analysis Software".

- Tippmann, Sylvia (29 December 2014). "Programming tools: Adventures with R". Nature. 517 (7532): 109–110. doi:10.1038/517109a. PMID 25557714.

- "TIOBE Index - The Software Quality Company". TIOBE. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- "TIOBE Index: The R Programming Language". TIOBE. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Kurt Hornik. The R FAQ: Why R?. ISBN 3-900051-08-9. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- Ihaka, Ross. "The R Project: A Brief History and Thoughts About the Future" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Hornik, Kurt; The R Core Team (12 April 2022). "R FAQ". The Comprehensive R Archive Network. 2.13 What is the R Foundation?. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Ihaka, Ross. "R: Past and Future History" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- GNU project

- "GNU R". Free Software Foundation. 23 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- R Project. "What is R?". Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- Maechler, Martin (1 April 1997). ""R-announce", "R-help", "R-devel" : 3 mailing lists for R". stat.ethz.ch. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Ihaka, Ross (5 December 1997). "New R Version for Unix". stat.ethz.ch. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Hornik, Kurt (2012). "The Comprehensive R Archive Network". WIREs Computational Statistics. 4 (4): 394–398. doi:10.1002/wics.1212. ISSN 1939-5108. S2CID 62231320.

- Kurt Hornik (23 April 1997). "Announce: CRAN". r-help. Wikidata Q101068595..

- "The Status of CRAN Mirrors". cran.r-project.org. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "CRAN - Contributed Packages". cran.r-project.org. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Hornik, Kurt; R Core Team (12 April 2022). "R FAQ". 2.1 What is R?. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Fox, John (2009). "Aspects of the Social Organization and Trajectory of the R Project". The R Journal. 1 (2): 5. doi:10.32614/RJ-2009-014. ISSN 2073-4859.

- "R: Contributors". R Project. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- Mächler, Martin; Hornik, Kurt (December 2014). "R Foundation News" (PDF). The R Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- Hornik, Kurt; R Core Team (12 April 2022). "R FAQ". 2.13 What is the R Foundation?. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Dalgaard, Peter (2002). Introductory Statistics with R. New York, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 10–18, 34. ISBN 0387954759.

- An Introduction to R, Section 5.1: Arrays. Retrieved in 2010-03 from https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/R-intro.html#Arrays.

- Chen, Han-feng; Wai-mee, Ching; Da, Zheng. "A Comparison Study on Execution Performance of MATLAB and APL" (PDF). McGill University. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Ihaka, Ross; Gentlman, Robert (September 1996). "R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics" (PDF). Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. American Statistical Association. 5 (3): 299–314. doi:10.2307/1390807. JSTOR 1390807. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "Data structures · Advanced R." adv-r.had.co.nz. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- "R: What is R?". R-project.org. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- White, Homer. 14.1 Programming Paradigms | Beginning Computer Science with R.

- Jackman, Simon (Spring 2003). "R For the Political Methodologist" (PDF). The Political Methodologist. Political Methodology Section, American Political Science Association. 11 (1): 20–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "An Introduction to R: 1.2 Related software and documentation". Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Eddelbuettel, Dirk; Francois, Romain (2011). "Rcpp: Seamless R and C++ Integration". Journal of Statistical Software. 40 (8). doi:10.18637/jss.v040.i08.

- "nution-j2r: Java library to invoke R native functions". Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- .NET Framework

- "Making GUIs using C# and R with the help of R.NET". 19 June 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "R.NET homepage". Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Haynold, Oliver M. (April 2011). An Rserve Client Implementation for CLI/.NET (PDF). R/Finance 2011. Chicago, IL, USA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- R manuals. "Writing R Extensions". r-project.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Functions · Advanced R." adv-r.had.co.nz.

- R Core Team. "Print Values". R Documentation. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- Hadley, Wickham; Bryan, Jenny. "R packages: Organize, Test, Document, and Share Your Code".

- Chambers, John M. (2020). "S, R, and Data Science". The R Journal. 12 (1): 462–476. doi:10.32614/RJ-2020-028. ISSN 2073-4859.

- Vance, Ashlee (6 January 2009). "Data Analysts Captivated by R's Power". New York Times.

- Tippmann, Sylvia (29 December 2014). "Programming tools: Adventures with R". Nature News. 517 (7532): 109–110. doi:10.1038/517109a. PMID 25557714.

- Thieme, Nick (2018). "R generation". Significance. 15 (4): 14–19. doi:10.1111/j.1740-9713.2018.01169.x. ISSN 1740-9713.

- widely used

- Fox, John & Andersen, Robert (January 2005). "Using the R Statistical Computing Environment to Teach Social Statistics Courses" (PDF). Department of Sociology, McMaster University. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Vance, Ashlee (6 January 2009). "Data Analysts Captivated by R's Power". New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

R is also the name of a popular programming language used by a growing number of data analysts inside corporations and academia. It is becoming their lingua franca...

- Marwick, Ben; Boettiger, Carl; Mullen, Lincoln (26 August 2017). "Packaging data analytical work reproducibly using R (and friends)". PeerJ Preprints. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.3192v1. ISSN 2167-9843.

- Theußl, Stefan; Zeileis, Achim (2009). "Collaborative Software Development Using R-Forge". The R Journal. 1 (1): 9. doi:10.32614/RJ-2009-007. ISSN 2073-4859.

- "Omegahat.net". Omegahat.net. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- packages available from repositories

- Robert A. Muenchen (2012). "The Popularity of Data Analysis Software".

- Tippmann, Sylvia (29 December 2014). "Programming tools: Adventures with R". Nature. 517 (7532): 109–110. doi:10.1038/517109a. PMID 25557714.

- "Search all R packages and function manuals | Rdocumentation". Rdocumentation. 16 June 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Wickham, Hadley; Bryan, Jennifer. Chapter 10 Object documentation | R Packages.

- "Rd formatting". cran.r-project.org. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- "CRAN Task Views". cran.r-project.org. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Hornik, Kurt; Zeileis, Achim (2013). "Changes on CRAN" (PDF). The R Journal. 5 (1): 239–264.

- "FDA: R OK for drug trials". Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "CRAN Time Machine. MRAN". Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "R-Forge: Welcome". Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Huber, W; Carey, VJ; Gentleman, R; Anders, S; Carlson, M; Carvalho, BS; Bravo, HC; Davis, S; Gatto, L; Girke, T; Gottardo, R; Hahne, F; Hansen, KD; Irizarry, RA; Lawrence, M; Love, MI; MacDonald, J; Obenchain, V; Oleś, AK; Pagès, H; Reyes, A; Shannon, P; Smyth, GK; Tenenbaum, D; Waldron, L; Morgan, M (2015). "Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor". Nature Methods. Nature Publishing Group. 12 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3252. PMC 4509590. PMID 25633503.

- Lewin-Koh, Nicholas (7 January 2015). "CRAN Task View: Graphic Displays & Dynamic Graphics & Graphic Devices & Visualization". Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- "Poll: R GUIs you use frequently (2011)". kdnuggets.com. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "R Programming - The State of Developer Ecosystem in 2020 Infographic". JetBrains: Developer Tools for Professionals and Teams. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- Stephan Wahlbrink. "StatET for R".

- "Work with R in Visual Studio". 13 November 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- "Nvim-R - Plugin to work with R : vim online". Vim.org. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Syntax Highlighting". Kate Development Team. Archived from the original on 7 July 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- Paul E. Johnson & Gregor Gorjanc. "LyX with R through Sweave". Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "NppToR: R in Notepad++". sourceforge.net. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Uwe Ligges (5 January 2017). "RWinEdt: R Interface to 'WinEdt'". Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "Tinn-R". Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- "Using the R programming language in Jupyter Notebook". Anaconda. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Gautier, Laurent. "rpy2 - R in Python". Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Florent Angly. "Statistics::R - Perl interface with the R statistical program". Metacpan.org.

- Alex Gutteridge (15 July 2021). "GitHub - alexgutteridge/rsruby: Ruby - R bridge". Github.com.

- BlueMountain Capital. "F# R Type Provider".

- "JuliaInterop/RCall.jl". Github.com. 2 June 2021.

- "Rserve - Binary R server - RForge.net". Rforge.net.

- "konne/RserveCLI2". Github.com. 8 March 2021.

- "R.NET". Jmp75.github.io. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- "r-source: Read only mirror of R source code on GitHub". GitHub. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Talbot, Justin; DeVito, Zachary; Hanrahan, Pat (1 January 2012). "Riposte: A trace-driven compiler and parallel VM for vector code in R". Proceedings of the 21st international conference on Parallel architectures and compilation techniques. ACM. pp. 43–52. doi:10.1145/2370816.2370825. ISBN 9781450311823. S2CID 1989369.

- Neal, Radford (25 July 2013). "Deferred evaluation in Renjin, Riposte, and pqR". Radford Neal's blog. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Jackson, Joab (16 May 2013). TIBCO offers free R to the enterprise. PC World. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "Home". mran.microsoft.com. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- "Microsoft R Open: The Enhanced R Distribution". Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- "Looking to the future for R in Azure SQL and SQL Server". 30 June 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- "R Ladies". R Ladies. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- "Conferences". The R Project for Statistical Computing. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- "satRdays". satrdays.org. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Bighetti, Nelson. "R Conference". R Conference. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- "posit::conf". Posit. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- R as competition for commercial statistical packages

- Vance, Ashlee (7 January 2009). "Data Analysts Are Mesmerized by the Power of Program R: [Business/Financial Desk]". The New York Times.

- Vance, Ashlee (8 January 2009). "R You Ready for R?". The New York Times.

- "SAS Supported Operating Systems". support.sas.com. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Hornik, Kurt; R Core Team (12 April 2022). "R FAQ". How can R be installed?. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Muenchen, Robert A. (2011). R for SAS and SPSS Users. Statistics and Computing (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 2–3. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0685-3. ISBN 978-1-4614-0684-6.

- Burns, Patrick (27 February 2007). "R Relative to Statistical Packages: Comment 1 on Technical Report Number 1 (Version 1.0) Strategically using General Purpose Statistics Packages: A Look at Stata, SAS and SPSS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Muenchen, Robert A.; Hilbe, Joseph M. (2010). R for Stata Users. Statistics and Computing. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 2–3. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1318-0. ISBN 978-1-4419-1317-3.

- Grogan, Michael (2018). Python vs. R for Data Science. O'Reilly Media, Inc.

- Morgan, Timothy Prickett (2011-02-07). "'Red Hat for stats' goes toe-to-toe with SAS". The Register, 7 February 2011. Retrieved from https://www.theregister.co.uk/2011/02/07/revolution_r_sas_challenge/.

- "Analyzing clinical trial data for FDA submissions with R". Revolution Analytics. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Sirosh, Joseph. "Microsoft Closes Acquisition of Revolution Analytics". blogs.technet.com. Microsoft. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Introducing R Tools for Visual Studio". Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Oracle Corporation's Big Data Appliance

- Doug Henschen (2012); Oracle Makes Big Data Appliance Move With Cloudera, InformationWeek, 10 January 2012.

- Jaikumar Vijayan (2012); Oracle's Big Data Appliance brings focus to bundled approach, ComputerWorld, 11 January 2012.

- Timothy Prickett Morgan (2011); Oracle rolls its own NoSQL and Hadoop Oracle rolls its own NoSQL and Hadoop, The Register, 3 October 2011.

- Chris Kanaracus (2012); Oracle Stakes Claim in R With Advanced Analytics Launch, PC World, February 8, 2012.

- Doug Henschen (2012); Oracle Stakes Claim in R With Advanced Analytics Launch Archived 27 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, InformationWeek, April 4, 2012.

- "What's New in IBM InfoSphere BigInsights v2.1.2". IBM. Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- "IBM PureData System for Analytics" (PDF). IBM. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- Tibco. "Unleash the agility of R for the Enterprise". Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- "ValidR on Mango website". Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Andy Nicholls at Mango Solutions. "ValidR Enterprise: Developing an R Validation Framework" (PDF). Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- FDA. "Statistical Software Clarifying Statement" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "An Introduction to R. Notes on R: A Programming Environment for Data Analysis and Graphics" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- R Development Core Team. "Assignments with the = Operator". Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- most used assignment operator in R is

<-- R Development Core Team. "Writing R Extensions". Retrieved 11 September 2018.

[...] we recommend the consistent use of the preferred assignment operator '<-' (rather than '=') for assignment.

- "Google's R Style Guide". Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- Wickham, Hadley. "Style Guide". Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- Bengtsson, Henrik (January 2009). "R Coding Conventions (RCC) – a draft". Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- R Development Core Team. "Writing R Extensions". Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- Kabacoff, Robert (2012). "Quick-R: User-Defined Functions". statmethods.net. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

External links

- Official website

of the R project

of the R project - R Technical Papers