Race and sexuality

Concepts of race and sexuality have interacted in various ways in different historical contexts. While partially based on physical similarities within groups, race is understood by scientists to be a social construct rather than a biological reality.[1][2] Human sexuality involves biological, erotic, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors.[3][4]

The ways in which people perceive the relationship between these two concepts implicitly informs attitudes toward interracial sexual relationships and sexual preferences for particular races expressed by individuals. Racial bias may involve a sexual dimension, which often takes the form of racial fetishism.[5][6][7][8]

Attitudes towards interracial relationships

In the United States before the Civil Rights Era

After the abolition of slavery in 1865, white Americans showed an increasing fear of racial mixing.[9] The remnants of the racial divide became stronger post-slavery as the concept of whiteness developed. There was a widely held belief that uncontrollable lust threatens the purity of the nation. This increased white anxiety about interracial sex, and has been described through Montesquieu's climatic theory in his book The Spirit of the Laws, which explains how people from different climates have different temperaments, "The inhabitants of warm countries are, like old men, timorous; the people in cold countries are, like young men, brave."[10] At the time, black women held the "Jezebel" stereotype, which claimed black women often initiated sex outside of marriage and were generally sexually promiscuous.[11] This idea stemmed from the first encounters between European men and African women. As the men were not used to the extremely hot climate, they misinterpreted the women's lack of clothing for vulgarity.[12]

There are a few potential reasons as to why such strong ideas on interracial sex developed. The Reconstruction Era which followed the Civil War started to disassemble traditional aspects of Southern society. Now, the Southerners who were used to being dominant were no longer legally allowed to run their farms by practicing slavery.[13] Many whites struggled with this reformation and they attempted to get around it by searching for legal loopholes which would have allowed them to continue their practice of exploiting black laborers. The Southern Democrats were not pleased with the outcome of this reformation. This radical reconstruction of the South was deeply unpopular and it slowly unraveled, leading to the introduction of Jim Crow laws.[14] There was an increase in the sense of white dominance and sexual racism among the Southern people.

Generally, tensions heightened after the end of the civil war in 1865, and as a result, the sexual anxiety which existed in the white population intensified. The Ku Klux Klan was formed in 1867, an event which triggered violence and terrorism which targeted the black population.[15] There was an increase in the number of acts of lynch-mob violence in which many black men were falsely accused of committing rape. These acts of violence were not just senseless, they were attempts to preserve 'whiteness' and prevent the blurring of racial distinctions; some racist whites wanted to maintain a system of racial separation and prevent the occurrence of interracial sexual activity. For example, mixed race couples that chose to live together were sought out and lynched by the KKK. The famous case of Emmett Till, who was lynched by two men when he was fourteen years old, shows the extent of the acts of violence which were committed against black people who flirted with white people. Till was lynched because the two men who lynched him believed that he had whistled at a white woman, but in actuality, he had whistled for his own reasons.[16] When Jim Crow laws were eventually overturned, it took years for the court to resolve the numerous acts of discrimination.

Challenges to attitudes

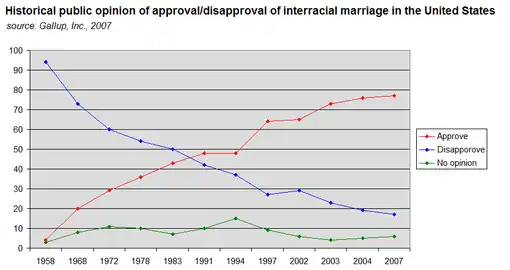

Sexual racism is presumed to exist in all sexual communities across the globe. The prevalence of interracial couples may demonstrate how attitudes have changed in the last 50 years.[17] A case that received heightened publicity is that of Mildred and Richard Loving. The couple lived in Virginia yet had to marry outside the state due to the anti-miscegenation laws present in nearly half of the US states in 1958. Once married, the pair returned to Virginia, and were both arrested in their home for the infringement of the Racial Integrity Act, and each sentenced to a year in prison, a sentence which was ultimately overturned by the United States Supreme Court.[18]

Around a similar time, the controversy involving Seretse and Ruth Khama broke out. Seretse was the chief of an eminent Botswanan tribe, and Ruth a British student. The pair married in 1948 but experienced frequent hardships from the onset of the relationship, including Seretse's removal from his tribal responsibilities as chief in Bechuanaland. For nearly 10 years, Seretse and Ruth lived as exiles in Britain, as the government refused to allow Seretse to return to Bechuanaland. Once the couple were allowed to return there in 1956, they became prominent campaigners for social equality, contributing to Seretse's election as president of the independent Botswana in 1966. Later, they continued campaigning for the legalization of interracial marriage around the globe.[19]

More recent examples portray the increasingly accepting attitudes of the majority to interracial relationships and marriage. In 1999, Jeb Bush was elected as Governor of Florida, accompanied by his wife, Columba, a Mexican woman he met in León who did not speak English when they met. They were one of the first interracial couples to stand in power side by side. Other prominent interracial couples in American politics are Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell and former Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao, as well as New York City mayor Bill de Blasio and his wife Chirlane McCray. The political success of these couples is seen by some to demonstrate that attitudes toward interracial marriage (at least in the United States) are much more positive and optimistic than in previous decades.[20] Across much of the world, it is ever increasingly the situation that interracial couples can live, marry and have children without prosecution that was previously rife, due to major changes in law along with reductions in discriminatory attitudes.

Sexual preferences

While discrimination among partners based on perceived racial identity has been asserted by some to be a form of racism, it is generally considered a matter of personal preference.[21] A study by Callander, Newman, and Holts quoted author Laurence Watts from the Huffington Post, who argued that sexual attraction and racism are not the same:[22]

Just because someone isn't sexually attracted to someone of Asian origin does not mean they wouldn't want to work, live next to, or socialize with him or her, or that they believe they are somehow naturally superior to them.

This suggests that people find it possible to view larger systemic racial preference as problematic, while viewing racial preferences in romantic or sexual personal relationships as not problematic. Researchers noted that racial preferences in one's own dating life were generally tolerated and that calling them "racist" is not a commonly accepted view.[21]

Online dating

In the twenty-first century, online dating has overtaken previously preferred methods of meeting with potential partners, surpassing both the occupational setting and area of residence as chosen locations. This spike is consistent with an increase in access to the internet in homes across the globe, in addition to the number of dating sites available to individuals differing in age, gender, race, sexual orientation and ethnic background.[23] Partner race is the most highly selected preference chosen by users when creating their online profiles, ahead of both educational and religious characteristics.[24] Research has indicated a progressive acceptance of interracial relationships by white individuals.[25] The majority of white Americans are not against interracial relationships and marriage,[26] though these beliefs do not imply that the person in question will pursue an interracial marriage themselves. Currently, fewer than 5% of white Americans wed outside their own race;[27] however this does not imply that whites are less likely to enter interracial relationships, because the larger size of the white population (relative to Asians or African-Americans) means that intermarriages do not make as large of an impact on white marriage rates as they do on non-white marriage rates.[28] In one study, African Americans appeared to be the most open to interracial relationships,[29] yet are the least preferred partner by other racial groups.[30] However, regardless of stated preferences, racial discrimination still occurs in online dating.[24]

Each group significantly prefers to date intra-racially. Beyond this, in the online dating world, preferences appear to follow a racial hierarchy.[31] White Americans are the least open to interracial dating, and select preferences in the order of Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans and then African American individuals last at 60.5%, 58.5% and 49.4% respectively.[29] African American preferences follow a similar pattern, with the most preferred partner belonging to the Hispanic group (61%), followed by white individuals (59.6%) and then Asian Americans (43.5%). Both Hispanic and Asian Americans prefer to date a white individual (80.3% and 87.3%, respectively), and both are least willing to date African Americans (56.5% and 69.5%).[30] In all significant cases, Hispanic Americans are preferred to Asian Americans, and Asian Americans are significantly preferred over African Americans.[29] Hispanic Americans are less likely to be excluded in online dating partner preferences by whites seeking a partner, as Latinos are often viewed as an ethnic group that is increasingly assimilating more into white American culture.[32]

Another aspect of racial preferences is that women of any race are significantly less likely to date inter-racially than a male of any race.[33] Specifically, Asian men and black men and women face more obstacles to acceptance online.[34] White women are the most likely to only date their own race, with Asian and black men being the most rejected groups by them.[35] The dating disadvantage of Asian men persisted even when they had advanced educational backgrounds and significantly higher incomes.[36][29] Increased education does however influence choices in the other direction, such that a higher level of schooling is associated with more optimistic feelings towards interracial relationships.[37] White men are most likely to exclude black women, as opposed to women of another race. High levels of previous exposure to a variety of racial groups is correlated with decreased racial preferences.[38] Racial preferences in dating are also influenced by the area of residence. Those residing in the south-eastern regions in American states are less likely to have been in an interracial relationship and are less likely to interracially date in the future.[39] People who engaged in regular religious customs at age 12 are also less likely to interracially date. Moreover, those from a Jewish background are significantly more likely to enter an interracial relationship than those from a Protestant background.[39]

A 2015 study of interracial online dating within multiple European countries, analyzing the dating preferences of Europeans, as well as Arabs (MENA), Africans, Asians (including South Asians and Hispanics, found that most races ranked Europeans as most preferred, followed by Hispanics and Asians as intermediately preferable, then by Arabs and finally Africans as the least preferred. Country-specific results were more variable, with more diverse countries showing more openness to engage in interracial dating. The researchers noted that Arabs tended to have higher same-race preferences in regions with higher Arabic populations, possibly due to more traditional cultural norms on marriage.[40]

Interracial preferences, dating, and intermarriages often vary by gender. In the United States, several studies have found that East Asian women are the most desired group of women,[41][42][43] while East Asian men are less desired.[44] Some view this to be the result of the hypersexualization of Asian women in popular media[42] while other studies attribute the higher rate of interracial marriages to a simple preference for Asian women's physical features.[45]

Currently, there are websites specifically targeted to different demographic preferences, such that singles can sign up online and focus on one particular partner quality, such as race, religious beliefs or ethnicity. In addition to this, there are online dating services that target race-specific partner choices, and a selection of pages dedicated to interracial dating that allow users to select partners based on age, gender and particularly race. Online dating services experience controversy in this context as debate is cast over whether statements such as "no Asians" or "not attracted to Asians" in user profiles are racist or merely signify individual preferences.[21]

Non-white ethnic minorities, mostly Indians and Asians,[46] who feel they lack dating prospects as a result of their race, sometimes refer to themselves as ricecels, currycels, or more broadly ethnicels,[47] a term related to the term incel.[48] Racial preferences are sometimes considered as a subset of lookism.[49]

LGBT community

Hoang Tan Nguyen, an Assistant Professor of English and Film Studies at Bryn Mawr College, wrote that Asian men are often feminized and desexualized by both mainstream and LGBT media.[50] The gay Asian-Canadian author Richard Fung has opined that he believes that while black men are portrayed as hypersexualized, gay Asian men are portrayed as being feminine.[51] According to Fung, gay Asian men tend to ignore or display displeasure with races such as Arabs, Blacks, and other Asians but seemingly give sexual acceptance and approval to gay white men.[52]

Within the transgender community and those attracted to trans women, women of East Asian descent are highly sought after, because of the racial stereotype that Asian women's features are 'prettier' than white women's. According to Chong-suk Han, this explains why East Asian drag queens typically win trans beauty pageants, because they are thought to pass more easily as female.[53] Charlie Anders notes that the best-selling transsexual pornographic films depict Asian transwomen, and they are highly esteemed and sought after by men identifying as heterosexual.[54]

Asian American women have reported a sense of invisibility in lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB) communities. According to a 2015 study, Asian American participants who identified as lesbian or bisexual often reported stereotyping, and fetishism in LGB circles and the larger U.S. culture, as well as low representation within the community, as minorities.[55]

In German gay male subculture, discriminatory attitudes have been reported, particularly towards obese or overweight men, feminine men, and Asian men.[56]

Racial preferences are also prevalent in gay online dating in the United States. Phua and Kaufman (2003) noted that men seeking men online were more likely than men seeking women to look at racial traits.[57] According to one study, LGBTQ+ people are significantly more likely to be in interracial relationships than heterosexual people.[58]

In a qualitative study conducted by Paul, Ayala, and Choi (2010) with Asian and Pacific Islanders (API), Latino, and African American men seeking men, participants interviewed endorsed racial preference as a common criterion in online dating partner selection.[59]

Racial bias

A 2015 study on sexual racism among gay and bisexual men found a strong correlation between test subjects' racist attitudes and their stated racial preferences.[21]

Philosopher Amia Srinivasan argued for racialized origins of Western beauty standards in her 2018 essay "Does anyone have the right to sex?", and stated that racial bias can shape sexual desire.[60]

Racial fetishism

Racial fetishism is sexually fetishizing a person or culture belonging to a specific race or ethnic group.[5][61][62]

Theories

Homi K. Bhabha explains racial fetishism as a version of racist stereotyping, which is woven into colonial discourse and based on multiple/contradictory and splitting beliefs, similar to the disavowal which Sigmund Freud discusses. Bhabha defines colonial discourse as that which activates the simultaneous "recognition and disavowal of racial/cultural/historical differences" and whose goal is to define the colonized as 'other', but also as fixed and knowable stereotypes. Racial fetishism involves contradictory belief systems where the 'other' is both demonized and idolized.[5]

The effects of racial fetishism as a form of sexual racism among gay men of color are discussed in research conducted by Mary Plummer. Plummer found that gay clubs and bars, casual sex encounters as well as romantic relationships frequently presented psychologically distressing situations for non-white gay men. These include lowered self-esteem, internalized sexual racism, and increased psychological distress in gay men of color, such as being expected to embody Asian racial stereotypes or to have stereotypically Asian racial characteristics, such as "smooth skin".[63]

Fetishism can take multiple forms and has branched off to incorporate different races. The theories of naturalist Darwin can offer some observations in regards to why some people might find other races more attractive than their own. Attraction can be viewed as a mechanism for choosing a healthy mate. People's minds have evolved to recognize aspects of other peoples' biology that makes them an appropriate or good mate. This area of theory is called optimal outbreeding hypothesis.[64]

White women

Rey Chow argues that the fetishism of white women in Chinese media has nothing to do with sex. Chow describes it as a type of commodity fetishism. White women, according to Chow, are seen as a representation of what China does not have: an image of a woman as something more than the heterosexual opposite to man.[65]

Perry Johansson argues that following the globalization of China, the perception of Westerners changed drastically. With the Opening of China to the outside world, representations of Westerners shifted from enemies of China to individuals of great power, money, and sophistication.[66] Chinese advertisements depict Western women as symbols of strength. The body language of Chinese models in ads expresses shyness and docility, while the body language of Western women demonstrates power and unashamedness. The study suggested White women represent are even presented with qualities otherwise considered to be "masculine" in Chinese culture.[66]

According to a 2014 study of Swedish women in Singapore, white women are not fetishized in East Asia, but placed beneath Asian women in the beauty hierarchy. European racial characteristics such as blond hair desexualized Swedish women in Singapore, and made them feel less feminine. Furthermore, their Swedish husbands found local Taiwanese women highly attractive, contributing to their low self esteem.[67]

White men

In China, White men are fetishized by Chinese women, who have stereotyped them as more masculine and better able to satisfy their sexual and emotional needs.[68] It has been reported that women in China seeking to have a child through in-vitro fertilisation have a tendency to select white men from America and Europe as sperm donors, even when Asian men are available in these countries as donors, because they are more attracted to white physical traits such as light hair or eye color. Women are forbidden from choosing sperm donors based on physical traits within China.[69]

Asian women

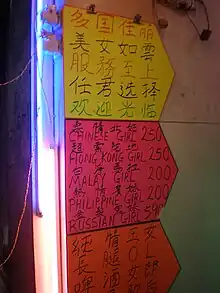

An Asian fetish focusing on East Asian, Southeast Asian women has been documented in Australasia, North America, and Scandinavia.[70][71][72][73]

According to a 2008 article from the Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice by Sunny Woan, the modern "Asian fetish" originates from Western imperialism. Western men deployed overseas found Asian women physically attractive, innocent, and sexually superior to white women.[74] These stereotypes became widespread when Western men returned to their home countries, and may be linked to the over-representation of Asian women in pornography, as well as the mail-order bride phenomenon.[74]

The girls follow Stefani around on tour and are contractually obligated not to speak English in public.[75] The performer had "renamed" them corresponding to her album title and clothing brand, L.A.M.B.: Love, Angel, Music, and Baby.[75]

A few cases of violence against Asian women, influenced by sexual stereotypes, have been reported in news media. In one case in 2000, two men, David Dailey and Edmund Ball, and a woman, Lana Vickery, abducted, blindfolded and raped two Japanese women in Washington.[76] Vickery said Ball specifically targeted these Japanese students because he thought that they were submissive and were less likely to report sexual abuse.[77] In another case, in 2005, Michael Lohman, a doctoral student at Princeton University, was charged by the state of New Jersey for reckless endangerment, theft, harassment as well as tampering with a food product, including cutting off Asian women's hair and tampering their food.[78]

Arab and Middle Eastern women

According to multiple articles, the West's fetishization of fully covered Arab women has led to the stereotype that Arab women and women from the Muslim world are oppressed and therefore submissive.[79][80][81] When French armies invaded Algeria, they had anticipated Algerian women to be sexually available and hookah smokers. To their surprise, Algerian women actually appeared to have been more modestly dressed and covered from their head to toes. Many French photographers paid Algerian women to remove part of their religious attire and pose for photos to make French postcards.[82] In his book Desiring Arabs, Joseph Massad talks about how the West's interpretation of Arab culture has painted the stereotype of Arab women being exotic and desirable. Massad's book was largely influenced by Edward Said's book Orientalism.[6][83]

Mixed race women/Latin woman

In her book Sex Tourism in Bahia Ambiguous Entanglements, Erica Lorraine Williams published the first full-length ethnography of sex tourism in Brazil, including interviews with tourists who come solely to participate in sexual tourism, which may be considered a form of racialized fetishism. One of the tourists interviewed described his experience, "I've had a thing for Latin, brown-skinned women since my early twenties. I'm from [a place] where there are a lot of blonde, white girls. Whatever you have, you like the opposite – they're exotic, intriguing."[84]

Black women

The fetishization of black women expanded during the Colonial Era, as some white male slave owners raped and sexually abused their black, female slaves. They justified their actions by labeling the women as hyper-sexual property. These labels solidified into what is commonly referred to as the "Jezebel" stereotype.[85] The opposite of this "Jezebel" identity or persona is the "Mammy" figure who loses all of her sexual agency and autonomy, and becomes an asexual figure. L. H. Stallings notes that the creation and identities for the Jezebel or Mammy figures are "dependent upon patriarchy and heterosexuality."[86] An example of racial fetishism within the colonial era is that of Sarah Baartman. Baartman's body was utilized as a means to develop an anatomically accurate representation of a black woman's body juxtaposed to that of a white European woman's body during the age of biological racism. The scientist studying her anatomy went as far as making a mold of Baartman's genitalia postmortem because she refused him access to examine her vaginal region while she was alive. The data collected on Baartman is the origin of the black female body stereotype, i.e. large buttocks and labia.[87]

Charmaine Nelson suggests that every nude painting feeds into the voyeuristic male gaze, but the way black women are painted has even more undertones. "The black female body defies the white male subject's desire for a single subject of 'pure' origin in two ways: firstly, through a sexual 'otherness' as woman, and secondly through a racial and color 'otherness' as black. It is the combined power of these two markers of social location which has enabled western artists to represent black women at the margins of societal boundaries of propriety." Nelson asserts that any black woman is considered a fetish in these paintings and that she is only viewed in a sexual lens.[62]

One of the more recent popular discourses around the fetishization of black women surrounds the release of Nicki Minaj's popular song, "Anaconda" in 2014. The entire song and music video revolves around the largeness of black women's bottoms. While some praise Minaj's work for its embrace of female sexuality, some criticized that this song continues to reduce black women to be the focus of the male gaze.[88] The 2020 song "WAP" ("Wet-Ass Pussy") by Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion received a similar mixed reception, with some outlets praising its embrace of black female sexuality and others claiming it was degrading or objectifying women of color.[89]

Black men

"Big black cock", usually shortened to "BBC", is a sexual slang and genre of ethnic pornography, that focuses on Black men with large penises.[90] The stereotype of larger penis size in black men has been subjected to scientific scrutiny, with inconclusive results. The theme is found in both straight and gay pornography.

In BDSM

There is also a practice in BDSM which involves fetishizing race called "raceplay".[91] Susanne Schotanus defined raceplay as "a sexual practice where the either imagined or real racial background of one or more of the participants is used to create this power-imbalance in a BDSM-scene, through the use of slurs, narratives and objects laden with racial history."[92] Feminist author Audre Lorde cautions that this kind of BDSM "operates in tandem with social, cultural, economic, and political patterns of domination and submission" creating the perpetuation of negative stereotypes for black women in particular.[93]

However, race play can also be used within BDSM as a curative practice for black individuals to take back their autonomy from a history of subjugation.[94] One BDSM Dominatrix explains that raceplay provides her with an "emotional sense of reparations".[95] "Violence for black female performers in BDSM becomes not just a vehicle of intense pleasure but also a mode of accessing and critiquing power."[96]

See also

- Afrophobia

- Anti-miscegenation laws

- Discrimination based on skin color

- Discrimination in the United States

- Ethnic pornography

- Gendered racism

- Interracial marriage

- Race and crime

- Racism against African Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Sexual capital#Race

- Sexual objectification

- Stereotypes of African Americans

- Stereotypes of groups within the United States

References

- Barnshaw, John (2008). "Race". In Schaefer, Richard T. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, Volume 1. SAGE Publications. pp. 1091–3. ISBN 978-1-45-226586-5.

- Gannon, Megan (February 5, 2016). "Race Is a Social Construct, Scientists Argue". Scientific American. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- Greenberg, Jerrold S.; Bruess, Clint E.; Oswalt, Sara B. (2016). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 4–10. ISBN 978-1-284-08154-1. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

Human sexuality is a part of your total personality. It involves the interrelationship of biological, psychological, and sociocultural dimensions. [...] It is the total of our physical, emotional, and spiritual responses, thoughts, and feelings.

- Bolin, Anne; Whelehan, Patricia (2009). Human Sexuality: Biological, Psychological, and Cultural Perspectives. Taylor & Francis. pp. 32–42. ISBN 978-0-7890-2671-2.

- Bhabha, Homi K. (June 1983). "The Other Question: Difference, Discrimination and the Discourses of Colonialism". Screen. 24 (6): 18–36. doi:10.1093/screen/24.6.18.

- Massad, Joseph (2007). Desiring Arabs. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226509600.

- Williams, Linda (2004). "Skin Flicks on the Racial Border: Pornography, Exploitation, and Interracial Lust". In Williams, Linda (ed.). Porn studies. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 271–308. ISBN 9780822333128.

- Poulson-Bryant, Scott (2005). Hung: A Meditation on the Measure of Black Men in America. New York. ISBN 9780385510028.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Yancey, George (March 15, 2019). "Experiencing Racism: Differences in the Experiences of Whites Married to Blacks and Non-Black Racial Minorities". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 38 (2): 197–213. doi:10.3138/jcfs.38.2.197.

- De Montesquieu, C. (1989). Montesquieu: The Spirit of the Laws. Cambridge University Press.

- West, Carolyn M. (1995). "Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical images of Black women and their implications for psychotherapy". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 32 (3): 458–466. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.32.3.458. ISSN 1939-1536.

- White, D.G. (1985). Ar'n't I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South. African American women's studies. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30406-0. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- Foner, E.; Mahoney, O. (2003). America's Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War.

- Kousser, J. M. (2003). "Jim Crow Laws". Dictionary of American History, vol. 4, pp. 479-480.

- Wade, W. C. (1998). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Whitfield, S. J. (1991). A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till. JHU Press.

- Mendelsohn, Gerald A.; Shaw Taylor, Lindsay; Fiore, Andrew T.; Cheshire, Coye (January 2014). "Black/White dating online: Interracial courtship in the 21st century". Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 3 (1): 2–18. doi:10.1037/a0035357. ISSN 2160-4142. S2CID 54038867.

- Moran, R. F. (2007). "Loving and the Legacy of Unintended Consequences". Wisconsin Law Review, 239, 240-281.

- Parsons, Neil (November 1, 1993). "The impact of Seretse Khama on British public opinion 1948–56 and 1978". Immigrants & Minorities. 12 (3): 195–219. doi:10.1080/02619288.1993.9974825. ISSN 0261-9288.

- Werner, D. & Mahler, H. (2014). "Primary health care: The Return of Health for All". World Nutrition, 5(4), 336-365.

- Callander, Denton; Newman, Christy E.; Holt, Martin (October 1, 2015). "Is Sexual Racism Really Racism? Distinguishing Attitudes Toward Sexual Racism and Generic Racism Among Gay and Bisexual White Men". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 44 (7): 1991–2000. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0487-3. ISSN 1573-2800. PMID 26149367. S2CID 7507490.

- Watts, Laurence (February 29, 2012). "Gay Men and Women Are Not More Racist". The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 16, 2016. As cited in Callander, Newman, and Holts, 2015, p. 1992.

- Rosenfeld, Michael J.; Thomas, Reuben J. (June 13, 2012). "Searching for a Mate". American Sociological Review. 77 (4): 523–547. doi:10.1177/0003122412448050. ISSN 0003-1224.

- Hitsch, Gunter J.; Hortacsu, Ali; Ariely, Dan (2007). "What makes you click? Mate preferences and matching outcomes in online dating". PsycExtra Dataset. doi:10.1037/e633982013-148.

- Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations (revised edition): Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Ludwig, J. (2004). "Acceptance of interracial marriage at record high". Gallup.com Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/11836/acceptance-interracial-marriage-record-high.aspx, 23.11.2016, 20:00pm.

- Qian, Zhenchao; Lichter, Daniel T. (February 2007). "Social Boundaries and Marital Assimilation: Interpreting Trends in Racial and Ethnic Intermarriage". American Sociological Review. 72 (1): 76. doi:10.1177/000312240707200104. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 145200056.

". To be sure, differences in population size for each group account for part of the racial/ethnic variation in intermarriage. For example, the Asian American population is much smaller in size than the white population, which means that one Asian American-white marriage affects the percentage intermarried much more for Asian Americans than for whites.

- Robnett, B., & Feliciano, C. (2011). "Patterns of racial-ethnic exclusion by internet daters". Social Forces, 89, 807-828.

- Yancey, George (February 1, 2009). "Crossracial Differences in the Racial Preferences of Potential Dating Partners: A Test of the Alienation of African Americans and Social Dominance Orientation". The Sociological Quarterly. 50 (1): 121–143. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.01135.x. ISSN 0038-0253. S2CID 143872921.

- "How modern dating encourages racial prejudice". November 9, 2018.

- Yancey, G. (2003). Who Is White? Latinos, Asians, and the New Black/Nonblack Divide. Lynne Rienner Pub.

- Simonson, Itamar; Kamenica, Emir; Iyengar, Sheena S.; Fisman, Raymond (May 1, 2006). "Gender Differences in Mate Selection: Evidence From a Speed Dating Experiment". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 121 (2): 673–697. doi:10.1162/qjec.2006.121.2.673. ISSN 0033-5533.

- Spell, Sarah A. (July 28, 2016). "Not Just Black and White". Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 3 (2): 172–187. doi:10.1177/2332649216658296. ISSN 2332-6492. S2CID 148478280.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Kao, Grace; Balistreri, Kelly Stamper; Joyner, Kara (November 2018). "Asian American Men in Romantic Dating Markets". Contexts. 17 (4): 48–53. doi:10.1177/1536504218812869. ISSN 1536-5042.

Recent headlines suggest that Asian men have not only reached parity with White men in terms of education and earnings, they may have surpassed them. In 2016, Pew reported that Asian American men earned 117% of what White men earned. There is no doubt that Asian American men have higher levels of education and income than Hispanic and Black men. These patterns would suggest a considerable advantage of Asian American men in the dating market, because scholars agree that men's economic success increases their desirability as partners. So why are Asian American men at such a dating disadvantage?

- Bobo, L. D. & Massagli, M. P. (2001). "Stereotyping and Urban Inequality." Urban Inequality; pp. 89–162. Lawrence, M. P. M.; Bobo, D. (eds.). New York: Russell Sage.

- Potârcă, Gina; Mills, Melinda (January 5, 2015). "Racial Preferences in Online Dating across European Countries". European Sociological Review. Oxford University Press (OUP). 31 (3): 326–341. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu093. ISSN 0266-7215.

- Perry, Samuel L. (July 10, 2016). "Religious Socialization and Interracial Dating". Journal of Family Issues. 37 (15): 2138–2162. doi:10.1177/0192513x14555766. ISSN 0192-513X. S2CID 145428097.

- Nedelman, Michael (August 8, 2018). "Online dating study: Are you chasing people 'out of your league'?". CNN.

- Zheng, Robin (October 2016). "Why Yellow Fever Isn't Flattering: A Case Against Racial Fetishes" (PDF). Journal of the American Philosophical Association. 2 (3): 406. doi:10.1017/apa.2016.25. ISSN 2053-4477.

- Mason, Corinne Lysandra (September 2, 2016). "Tinder and humanitarian hook-ups: the erotics of social media racism". Feminist Media Studies. 16 (5): 822–837. doi:10.1080/14680777.2015.1137339. ISSN 1468-0777.

- Tsunokai, Glenn T.; McGrath, Allison R.; Kavanagh, Jillian K. (September 2014). "Online dating preferences of Asian Americans". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 31 (6): 796–814. doi:10.1177/0265407513505925. ISSN 0265-4075.

- Stephen, Ian D.; Salter, Darby L. H.; Tan, Kok Wei; Tan, Chrystalle B. Y.; Stevenson, Richard J. (2018). "Sexual dimorphism and attractiveness in Asian and White faces". Visual Cognition. 26 (6): 442–449. doi:10.1080/13506285.2018.1475437. ISSN 1350-6285.

- "Misogynist Incels and Male Supremacism". New America. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- "The foundational misogyny of incels overlaps with racism". The Star. May 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- "When Women are the Enemy: The Intersection of Misogyny and White Supremacy". www.adl.org. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- Davis, Andrew. "'Lookism', Common Schools, Respect and Democracy". Journal of Philosophy of Education 41.4 (2007): 811-827.

- Nguyen 2014.

- Gross & Woods 1999, pp. 235–253.

- Williams, L. (2004). Porn Studies. Book collections on Project MUSE (in German). Duke University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-8223-3312-8. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- Han, Chong-suk (2009). "Asian Girls Are Prettier: Gendered Presentations as Stigma Management among Gay Asian Men". Symbolic Interaction. Wiley. 32 (2): 112, 119–120. doi:10.1525/si.2009.32.2.106. ISSN 0195-6086.

p.112: "For gay Asian men, their perceived feminine traits allow them to manipulate the illusion and appear more "real" than white drag queens. For example, one white drag queen was quoted as saying, "I'm never entering another pageant with Asian girls again. . . . they're just too hard to beat. They're just way too real, it's not even fair" (Han 2005:83)"..."Because gay Asian men are perceived in the gay community to be more feminine than gay white men, they are better able to convince judges and audience members that they have achieved "realness," thereby winning multiple drag titles."

- "When Fetishes Collide". Hyphen. September 1, 2005. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

Many prefer transwomen who haven't had genital reconstruction surgery, because they find an otherwise female body with a penis sexy. And many trans admirers also actively seek out Asian girls above all others. Many tranny chasers believe that male-born Asians have an easier time appearing convincingly female because of facial features or less body hair. Look on any dating/hookup service for men-for-trans (M4T) posts and you'll find "Asian only" or "Asian preferred" all over the place. The top-selling transsexual porn videos, according to industry trade magazine Adult Video News, depict Asian transwomen"...

- Sung, Mi Ra; Szymanski, Dawn M.; Henrichs-Beck, Christy (2015). "Challenges, coping, and benefits of being an Asian American lesbian or bisexual woman". Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1037/sgd0000085.

- "Intoleranz unter schwulen und bi Männern | anyway" (in German). Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- Phua, Voon C.; Kaufman, Gayle (2003). "The Crossroads of Race and Sexuality: Date Selection Among Men in Internet 'Personal' Ads". Journal of Family Issues. 24 (8): 981–994. doi:10.1177/0192513x03256607. S2CID 11222750.

- Rohlinger, D.A.; Sobieraj, S. (2022). The Oxford Handbook of Digital Media Sociology. Oxford Handbooks Series. Oxford University Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-19-751063-6. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- Paul, Jay P.; Ayala, George; Choi, Kyung-Hee (November 2, 2010). "Internet Sex Ads for MSM and Partner Selection Criteria: The Potency of Race/Ethnicity Online". The Journal of Sex Research. 47 (6): 528–538. doi:10.1080/00224490903244575. ISSN 0022-4499. PMC 3065858. PMID 21322176.

- Srinivasan, Amia (March 22, 2018). "Does anyone have the right to sex?". The London Review of Books. Nicholas Spice. 40 (6). Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- McClintock, Anne (1995). Imperial Leather: Race Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge.

- Mercer, Kobena (1993). "Reading Racial Fetishism: The Photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe". In Apter, Emily; Pietz, William (eds.). Fetishism as Cultural Discourse. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Plummer, Mary Dianne (2007). Sexual racism in gay communities: negotiating the ethnosexual marketplace. Scholarly Publishing Services (Thesis). pp. 53–55. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- "Cross-cultural dating: Why are some people only attracted to one ethnicity?". News. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- Chow, Rey (1991). Mohanty, Chandra Talpade; Russo, Ann; Torres, Lourdes (eds.). Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism. Indiana University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-253-20632-9.

- Johansson, Perry (November 1, 1999). "Consuming the other: The fetish of the western woman in Chinese advertising and popular culture". Postcolonial Studies. 2 (3): 377–388. doi:10.1080/13688799989661. ISSN 1368-8790.

- Lundström, C. (2014). White Migrations: Gender, Whiteness and Privilege in Transnational Migration. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-137-28919-3. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

...the Singaporean society made the women feel 'less feminine' and unable to embody the local Asian feminine ideal...On the other hand, desexualization was comprehensive to an extent that deprived them of a sense of heterosexual desirability. In this way, their embodied version of European whiteness weakened their femininity.

- Liu, M. (2022). Seeking Western Men: Email-Order Brides under China's Global Rise. Globalization in Everyday Life. Stanford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-5036-3374-2. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- "Why single women in China use foreign sperm to have babies". South China Morning Post. December 10, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- "Playboy Petrarch: Racial Fetishism and K-pop". SeoulBeats. February 21, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- King, Ritchie (November 20, 2013). "The uncomfortable racial preferences revealed by online dating". Quartz. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- Ren, Yuan (July 2014). "'Yellow fever' fetish: Why do so many white men want to date a Chinese woman?".

- Chou, Rosalind S. (January 5, 2015). Asian American Sexual Politics: The Construction of Race, Gender, and Sexuality. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 65. ISBN 9781442209251.

- Woan, Sunny (March 2008). "White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence". Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice. 14 (2): 2, 19. ISSN 1535-0843.

American military men stationed in Asia brought back to the United States their stereotypes of Asian women as "cute, doll-like, and unassuming, with extraordinary sexual powers," which then became an expectation White men had of all women of Asian descent.137 This section addresses the negative, often dark, ramifications the hyper-sexed stereotype has caused.

- Ahn, Mihi (April 9, 2005). "Gwenihana". Salon. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- Geranios, Nicholas K. (December 31, 2000). "Abduction and Rape of 2 Japanese Students Outrages Spokane". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- "Rapists bet on victims' silence – and lose". Seattle Times. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- "For Asian women, 'fetish' is less than benign". Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- Rich, Janine (Fall 2014). "'Saving' Muslim Women: Feminism, U.S. Policy and the War on Terror" (PDF). USFCA.edu. University of San Francisco. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2021.

- Abdulrahim, Safa'a (June 2013). "Between Empire and Diaspora: Identity Poetics in Contemporary Arab-American Women's Poetry" (PDF). DSpace.Stir.ak.uk. STORRE: Stirling Online Research Repository, University of Stirling. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2023.

- Platt, Kaylee (August 12, 2014). Women and the Islamic Veil: Deconstructing implications of orientalism, state, and feminism through an understanding of performativity, cultivation of piety and identity, and fashion (PDF). Hofstra.edu (MA). Hofstra University. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2022.

- Sentilles, Sarah (October 5, 2017). "Colonial Postcards and Women as Props for War-making". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Said, Edward (1978). Orientalism.

- Williams, Erica Lorraine (2013). Sex Tourism in Bahia Ambiguous Entanglements. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- West, Carolyn M. "Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire and their homegirls: Developing an 'oppositional gaze' toward the images of Black women" 4th New York Lectures on the Psychology of Women (2008) pp. 286–299.

- Stallings, L. H. (2007). Mutha is Half a Word: Intersections of Folklore, Vernacular, Myth and Queerness in Black Female Culture. Ohio State University Press.

- Lederman, Muriel; Bartsch, Ingrid, eds. (2001). The Gender and Science Reader. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415213576. OCLC 44426765.

- Lhooq, Michelle (August 23, 2014). "Shocked and outraged by Nicki Minaj's Anaconda video? Perhaps you should butt out". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- Holt, Brianna (August 9, 2020). "Why Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion's Empowering Anthem 'WAP' Is So Important". Complex. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- "BBC » What does BBC mean? » Slang.org". Slang.org.

- "Exploring the controversial fetish of race play". Metro. DMG Media. November 3, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Schotanus, Susanne (April 20, 2017). "Racism or Race Play: A Conceptual Investigation of the Race Play Debates". Zapruder World. 4. doi:10.21431/Z3001F.

- Cruz, Ariane (2016). The color of kink : black women, BDSM, and pornography. New York: New York University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4798-9942-5. OCLC 992466612.

- Cruz, Ariane (2016). The color of kink : black women, BDSM, and pornography. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-9942-5. OCLC 992466612.

- "Meet The Dominatrix Who Requires The Men Who Hire Her To Read Black Feminist Theory". HuffPost. February 13, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- Cruz, Ariane (2016). The color of kink : black women, BDSM, and pornography. New York: New York University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4798-9942-5. OCLC 992466612.

Bibliography

- Gross, Larry P.; Woods, James D., eds. (1999). The Columbia Reader on Lesbians and Gay Men in Media, Society, and Politics. Between Men—Between Women. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10446-3.

- Marubbio, M. Elise (2006). Killing the Indian Maiden: Images of Native American Women in Film. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2414-8.

- Nguyen, Hoang Tan (2004). "The Resurrection of Brandon Lee: The Making of a Gay Asian American Porn Star". In Williams, Linda (ed.). Porn Studies. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 223–270. ISBN 978-0-8223-3300-5.

- ——— (2014). A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation. Perverse Modernities. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-5684-4.

Further reading

- Kudler, Benjamin A. (2007). Confronting Race and Racism: Social Identity in African American Gay Men (MSW thesis). Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Lay, Kenneth James (1993). "Sexual Racism: A Legacy of Slavery". National Black Law Journal. 13 (1): 165–183. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Lilly, J. Robert; Thomson, J. Michael (1997). "Executing US Soldiers in England, World War II: Command Influence and Sexual Racism". The British Journal of Criminology. 37 (2): 262–288. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a014158. JSTOR 23638647.

- Plummer, Mary Dianne (2007). Sexual Racism in Gay Communities: Negotiating the Ethnosexual Marketplace (PhD thesis). Seattle: University of Washington. hdl:1773/9181.

- Stevenson, Howard C, Jr. (1994). "The Psychology of Sexual Racism and AIDS: An Ongoing Saga of Distrust and the 'Sexual Other'". Journal of Black Studies. 25 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1177/002193479402500104. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 2784414. S2CID 144716464.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)