Radicalism in the United States

"Radicalism" or "radical liberalism" was a political ideology in the 19th century United States aimed at increasing political and economic equality. The ideology was rooted in a belief in the power of the ordinary man, political equality, and the need to protect civil liberties.

| Part of a series on |

| Radicalism |

|---|

Overview

Upon the founding of the United States, many ideas later associated with Radicalism were staples of American political life, it was not to the same degree. For example, while separation of church and state was enshrined in the first amendment, many states continued not allowing "blasphemers" to run for office and paid churches out of the public treasury.[1] Additionally, many states had wealth and property requirements for voting. Most property requirements were done away with by the 1820s, with North Carolina being the last state to do so in 1856.[2][3]

One of the first major factions that might be characterized as radical are the Jeffersonian Republicans,[4] and by extension the various Democratic-Republican Societies and the Democratic-Republican Party that rallied behind Thomas Jefferson. The party believed in expansionism, social mobility,[5] frequently defended the French Revolution[6] until Napoleon took power,[7] and, though open to some redistributive measures, saw a strong centralized government as a threat to freedom.[8]

The Radical faction of the Democratic-Republican party eventually became the Democrats, a populist political movement that advocated for the political equality of white men.[9] A faction of the Democrats that could be characterized as Radical is the Locofocos, originally known as the Equal Rights Party. They were vigorous advocates for laissez-faire economics and trade unionism, and were opposed to state banks and monopolies.

While Slavery was becoming a more divisive issue among Americans, the term "Radical" eventually became synonymous with Northerners opposed to Slave Power.[10] Many abolitionist Democrats, called "Barnburners" in New York, began leaving the party in favor of others, such as the Free Soil Party, during this period.[11] These abolitionist Democrats, Conscience Whigs and European Revolutionaries fleeing after the largely unsuccessful Revolutions of 1848, eventually formed the backbone of the Radical faction of the Republican party.

While Radical Republicans were not unified in regards to many issues in their early years, they were unified in their desire for the immediate complete abolition of slavery, belief in the predominance of Free Labor (both agricultural and industrial) over Slave Labor, support of Land Reform, suffrage expansion, opposition to the Southern Aristocracy, and belief in civil rights for emancipated slaves.

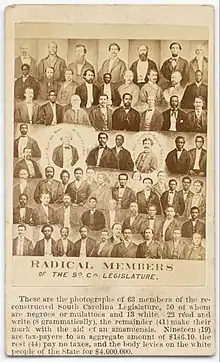

The ideology reached its peak relevance during the Reconstruction period following the Civil War. Radical Republicans sought to guarantee civil rights for African Americans, ensure that the former Confederate states had limited power in the federal government, and promote free market capitalism in the South in place of a slave based economy. Many Radical Republicans were also supportive of Labor Unions, though this element would fade over time. Many liberal Radical Republicans, (Liberal in this case meaning pro-free trade, civil service reform, federalism, and generally soft money) such as Charles Sumner and Lyman Turnbull, eventually began to leave the faction for other parties and Republican factions as Reconstruction wore on to a point considered excessive and the corruption of many hardliners became evident.[12][13]

The remaining radicals after this came to be referred to as the Stalwarts, and were from thereon marked primarily their advocacy of spoils system politics and African-American civil rights.[14] It was eventually succeeded as a liberal egalitarian left leaning ideology by Populism and later Progressivism.

According to Gene Clanton's study of Kansas from 1880s to 1910s, populism and progressivism in Kansas had similarities but different policies and distinct bases of support. Both opposed corruption and trusts. Populism emerged earlier and came out of the farm community. It was radically egalitarian in favor of the disadvantaged classes; it was weak in the towns and cities except in labor unions. Progressivism, on the other hand, was a later movement. It emerged after the 1890s from the urban business and professional communities. Most of its activists had opposed populism. It was elitist, and emphasized education and expertise. Its goals were to enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and enlarge the opportunities for upward social mobility. However, some former Populists changed their emphasis after 1900 and supported progressive reforms.[15]

Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were referred to as radicalist because they supported social-liberal reforms.[16][17]

Timeline

1824: The Jacksonian faction of the Democratic-Republicans is formed after the Presidential Election of that year.

1826: The Jacksonian Democratic Party is formed.

1828: Andrew Jackson wins the 1828 Presidential Election. This is the first election in which non-property-owning white males can vote in most states.

1832: Andrew Jackson is re-elected.

1833: American Anti-Slavery Society is founded by William Lloyd Garrison, Arthur Tappan, and Frederick Douglass.

1835: The Locofoco faction of the Democratic Party is established.

1836: Andrew Jackson's secretary of state, Martin Van Buren, wins the 1836 Presidential Election.

1840: The abolitionist Liberty Party is formed.

1848: The Mexican–American War is won, making the westward expansion of Slavery a prominent political issue. The Free Soil Party, opposed to the expansion of slavery, is formed, attracting the vote of many anti-slavery Democrats.

1850: The Compromise of 1850 is passed, temporarily settling the issue of slavery, but infuriating many who were pro-slavery and anti-slavery.

1854: The Kansas-Nebraska Act is passed, leading to Bleeding Kansas and the breakup of the Whig Party. The Republican Party, and by extension the Radical Republican Faction, is formed.

1860: Republican Abolitionist Abraham Lincoln wins the Presidential Election, serving as the catalyst for the civil war.

1864: The Radical Democracy Party forms to oppose Lincoln in the 1864 election, but later drops out due to not wanting to act as a spoiler. Abraham Lincoln is re-elected. The civil war ends.

1865: Abraham Lincoln is assassinated and his vice president, confederate sympathizer Andrew Johnson, is sworn into office.

1867: The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry is formed.

1868: Radical Republican Ulysses S. Grant wins the presidential election. The radical government passes the Fourteenth Amendment.

1870: Republicans disillusioned with the extent of Reconstruction and the corruption of the Republicans form the Liberal Republican Party. The Fifteenth Amendment, giving African Americans the right to vote, is ratified. the Enforcement Act of 1870 is passed to protect the new voting rights of African Americans and fight white supremacist paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

1872: Grant is re-elected by a landslide, causing the Liberal Republicans to disband.

1873: The Anti-Monopoly Party is formed.

1874: The Greenback Party is formed.

1875: The Southern Farmers' Alliance is formed.

1877: The Northern Farmers' Alliance is formed.

1876: Rutherford B. Hayes is sworn into office as a result of the Compromise of 1877, ending reconstruction and federal protection of the African American population of the south.

1880: Ulysses S. Grant fails to win a third Republican Nomination.

1881: The Readjuster Party is formed.

1886: The Colored Farmers' Alliance is formed.

1890: The Sherman Antitrust Act is signed into law, making cartels and certain anti-competitive actions illegal.

1892: The Farmers' Alliances form a third party, the People's Party, also known as the Populist Party. While it initially tries to win the black vote from the Republicans, much of it would eventually gain a more white supremacist character. They would go on to win 11 house seats, 3 senate seats, and the Colorado Governorship in the following midterms.

1894: The Republican and Populist parties of North Carolina begin collaborating via electoral fusion. This coalition included African Americans, causing significant gains for civil rights in the state.

1896: The Populist Party nominates Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan to be President after his Cross of Gold speech, though with a different Vice President. This proves to be disastrous for the party, with the Democrats significantly sapping away at the base of the Populists. The populists would never recover from this, and would be a shadow of their former selves.

1898: The Democrats launch a white supremacy campaign against the biracial fusionist North Carolina Government, culminating in the massacre of Wilmington's black population and overthrow of the local government.

1900: The first President of the Progressive Era, William McKinley, is elected.

1901: William McKinley is shot, and his progressive Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt, enters office.

1904: Theodore Roosevelt is re-elected.

1908: Theodore Roosevelt's hand picked successor, William Howard Taft, is elected president.

1910: The United States Postal Savings System is established.

1912: Theodore Roosevelt, perceiving the Republican Party as not progressive enough, forms the Progressive Party, splitting the Republican vote and allowing Woodrow Wilson to claim victory in the 1912 election.

1913: The Sixteenth Amendment is ratified, allowing a federal level progressive income tax. The Seventeenth Amendment is ratified, making senators directly elected.

1914: The Clayton Antitrust Act and Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 are passed, outlawing certain unfair trade practices and monopolies.

1916: Woodrow Wilson is re-elected.

1919: The Nineteenth Amendment is ratified, granting women the right to vote.

References

- Sehat, David (April 22, 2011). "Five myths about church and state in America". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Engerman & Sokoloff 2005, p. 14"Property- or tax-based qualifications were most strongly entrenched in the original thirteen states, and dramatic political battles took place at a series of prominent state constitutional conventions held during the late 1810s and 1820s."

- "Who got the right to vote when?". Al Jazeera. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- Matthews, Richard K. (1984). The radical politics of Thomas Jefferson: a revisionist view. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. p. 18. ISBN 0-7006-0256-9. OCLC 10605658.

- Brown (1999), p. 19.

- Reichley (2000), pp. 35–36.

- Wilentz (2005), p. 108.

- Reichley (2000), pp. 55–56.

- Eugenio F. Biagini, ed. (2004). Liberty, Retrenchment and Reform: Popular Liberalism in the Age of Gladstone, 1860-1880. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780521548861.

... which was one of the recurrent themes in European and in particular American radicalism : Jacksonian democrats were ...

- Victor B. Howard (2015). Religion and the Radical Republican Movement, 1860–1870. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-6144-0.

- Sean Wilentz, "Politics, Irony, and the Rise of American Democracy." Journal of The Historical Society 6.4 (2006): 537-553, at p. 538, summarizing his book The rise of American democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (2006).

- Slap, Andrew L. (3 May 2010). The Doom of Reconstruction: The Liberal Republicans in the Civil War Era. Fordham University Press. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-0-8232-2711-2.

- Summers (1994), Chapter 15.

- Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper & Row.

- Gene Clanton, "Populism, Progressivism, and Equality: The Kansas Paradigm" Agricultural History (1977) 51#3 pp.559-581.

- Gilbert Abcarian, ed. (1971). American Political Radicalism: Contemporary Issues and Orientations. Xerox College Pub.

- Jacob Kramer, ed. (2017). The New Freedom and the Radicals: Woodrow Wilson, Progressive Views of Radicalism, and the Origins of Repressive Tolerance. Temple University Press.

Sources

- Brown, David (1999). "Jeffersonian Ideology and the Second Party System". Wiley. 62 (1): 17–30. JSTOR 24450533.

- Engerman, Stanley L.; Sokoloff, Kenneth L. (February 2005). "The Evolution of Suffrage Institutions in the New World" (PDF). Yale Workshops and Seminars.

- Reichley, A. James (2000) [1992]. The Life of the Parties: A History of American Political Parties (Paperback ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-0888-9.

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren (1994). The Press Gang: Newspapers and Politics, 1865-1878. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807844465.

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-05820-4.