Rain shadow

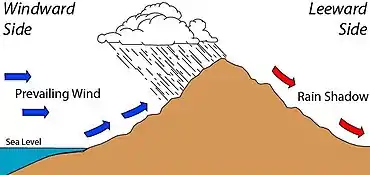

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from water bodies (such as oceans and large lakes) is carried by the prevailing onshore breezes towards the drier and hotter inland areas. When encountering elevated landforms, the moist air is driven upslope towards the peak, where it expands, cools, and its moisture condenses and starts to precipitate. If the landforms are tall and wide enough, most of the humidity will be lost to precipitation over the windward side (also known as the rainward side) before ever making it past the top. As the air descends the leeward side of the landforms, it is compressed and heated, producing foehn winds that absorb moisture downslope and cast a broad "shadow" of dry climate region behind the mountain crests. This climate typically takes the form of shrub–steppe, xeric shrublands or even deserts.

The condition exists because warm moist air rises by orographic lifting to the top of a mountain range. As atmospheric pressure decreases with increasing altitude, the air has expanded and adiabatically cooled to the point that the air reaches its adiabatic dew point (which is not the same as its constant pressure dew point commonly reported in weather forecasts). At the adiabatic dew point, moisture condenses onto the mountain and it precipitates on the top and windward sides of the mountain. The air descends on the leeward side, but due to the precipitation it has lost much of its moisture. Typically, descending air also gets warmer because of adiabatic compression (as with foehn winds) down the leeward side of the mountain, which increases the amount of moisture that it can absorb and creates an arid region.[1]

Regions of notable rain shadow

There are regular patterns of prevailing winds found in bands round Earth's equatorial region. The zone designated the trade winds is the zone between about 30° N and 30° S, blowing predominantly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere.[2] The westerlies are the prevailing winds in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude, blowing predominantly from the southwest in the Northern Hemisphere and from the northwest in the Southern Hemisphere.[3] Some of the strongest westerly winds in the middle latitudes can come in the Roaring Forties of the Southern Hemisphere, between 30 and 50 degrees latitude.[4]

Examples of notable rain shadowing include:

Northern Africa

- The Sahara is made even drier because of two strong rain shadow effects caused by major mountain ranges (whose highest points can culminate to more than 4,000 meters high). To the northwest, the Atlas Mountains, covering the Mediterranean coast for Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia as well as to the southeast with the Ethiopian Highlands, located in Ethiopia around the Horn of Africa. On the windward side of the Atlas Mountains, the warm, moist winds blowing from the northwest off the Atlantic Ocean which contain a lot of water vapor are forced to rise, lift up and expand over the mountain range. This causes them to cool down, which causes an excess of moisture to condense into high clouds and results in heavy precipitation over the mountain range. This is known as orographic rainfall and after this process, the air is dry because it has lost most of its moisture over the Atlas Mountains. On the leeward side, the cold, dry air starts to descend and to sink and compress, making the winds warm up. This warming causes the moisture to evaporate, making clouds disappear. This prevents rainfall formation and creates desert conditions in the Sahara. The same phenomenon occurs in the Ethiopian Highlands, but this rain shadow effect is even more pronounced because this mountain range is larger, with the tropical Monsoon of South Asia coming from the Indian Ocean and from the Arabian Sea. These produce clouds and rainfall on the windward side of the mountains, but the leeward side stays rain shadowed and extremely dry. This second extreme rain shadow effect partially explains the extreme aridity of the eastern Sahara Desert, which is the driest and the sunniest place on the planet.

- Desert regions in the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia and Djibouti) such as the Danakil Desert are all influenced by the air heating and drying produced by rain shadow effect of the Ethiopian Highlands, too.

Southern Africa

- The windward side of the island of Madagascar, which sees easterly on-shore winds, is wet tropical, while the western and southern sides of the island lie in the rain shadow of the central highlands and are home to thorn forests and deserts. The same is true for the island of Réunion.

- On Tristan da Cunha, Sandy Point on the east coast is warmer and drier than the rainy, windswept settlement of Edinburgh of the Seven Seas in the west.

- In Western Cape Province, the Breede River Valley and the Karoo region lie in the rain shadow of the Cape Fold Mountains and are arid; whereas the wettest parts of the Cape Mountains can receive 1,500 millimetres (59 in), Worcester receives only around 200 millimetres (8 in) and is useful only for grazing.

Central and Northern Asia

- The Himalaya and connecting ranges also contribute to arid conditions in Central Asia including Mongolia's Gobi desert, as well as the semi-arid steppes of Mongolia and north-central to north western China.

- The Verkhoyansk Range in eastern Siberia is the coldest place in the Northern Hemisphere, because the moist southeasterly winds from the Pacific Ocean lose their moisture over the coastal mountains well before reaching the Lena River valley, due to the intense Siberian High forming around the very cold continental air during the winter. One effect in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) is that, in Yakutsk, Verkhoyansk, and Oymyakon, the average temperature in the coldest month is below −38 °C (−36 °F). These regions are synonymous with extreme cold.

Eastern Asia

- The Ordos Desert is rain shadowed by mountain chains including the Kara-naryn-ula, the Sheitenula, and the Yin Mountains, which link on to the south end of the Great Khingan Mountains.

- The central region of Myanmar is in the rain shadow of the Arakan Mountains and is almost semi-arid with only 750 millimetres (30 in) of rain, versus up to 5.5 metres (220 in) on the Rakhine State coast.

- The plains around Tokyo, Japan - known as Kanto plain - in the winter months experiences significantly less precipitation than the rest of the country by virtue of surrounding mountain ranges, including the Japanese Alps, blocking prevailing northwesterly winds originating in Siberia.

Southern Asia

- The eastern side of the Sahyadri ranges on the Deccan Plateau including: North Karnataka and Solapur, Beed, Osmanabad, the Vidharba Plateau and the eastern side of Kerala and western Tamil Nadu in India.

- Gilgit and Chitral, Pakistan, are rainshadow areas.

- The Thar Desert is bounded and rain shadowed by the Aravalli ranges to the southeast, the Himalaya to the northeast, and the Kirthar and Sulaiman ranges to the west.

Western Asia

- The peaks of the Caucasus Mountains to the west and Hindukush and Pamir to the east rain shadow the Karakum and Kyzyl Kum deserts east of the Caspian Sea, as well as the semi-arid Kazakh Steppe. They also cause vast rainfall differences between coastal areas on the Black Sea such as Rize, Batumi and Sochi contrasted with the dry lowlands of Azerbaijan facing the Caspian Sea.

- The semi-arid Anatolian Plateau is rain shadowed by mountain chains, including the Pontic Mountains in the north and the Taurus Mountains in the south.

- The High Peaks of Mount Lebanon rain-shadow the northern parts of the Beqaa Valley and Anti-Lebanon Mountains.

- The Judaean Desert, the Dead Sea and the western slopes of the Moab Mountains on the opposite (Jordanian) side are rain-shadowed by the Judaean Mountains.

- The Dasht-i-Lut in Iran is in the rain shadow of the Elburz and Zagros Mountains and is one of the most lifeless areas on Earth.

- The peaks of the Zagros mountains rain-shadow the northern half of the West Azerbaijan province in Iranian Azerbaijan (above Urmia), as manifested by the province's dry winters relative to those in the windward part of the region (i.e. Kurdistan Region and Hakkâri Province in Turkey).

Central Europe

- The Plains of Limagne and Forez in the northern Massif Central, France are also relatively rainshadowed (mostly the plain of Limagne, shadowed by the Chaîne des Puys (up to 2000 mm of rain a year on the summits and below 600mm at Clermont-Ferrand, which is one of the driest places in the country).

- The Piedmont wine region of northern Italy is rainshadowed by the mountains that surround it on nearly every side: Asti receives only 527 mm of precipitation per year, making it one of the driest places in mainland Italy.[5]

- Some valleys in the inner Alps are also strongly rainshadowed by the high surrounding mountains: the areas of Gap and Briançon in France, the district of Zernez in Switzerland.

- The Kuyavia and the eastern part of the Greater Poland has an average rainfall of about 450 mm because of rainshadowing by the slopes of the Kashubian Switzerland, making it one of the driest places in the North European Plain.[6]

Northern Europe

- The Pennines of Northern England, the mountains of Wales, the Lake District and the Highlands of Scotland create a rain shadow that includes most of the eastern United Kingdom, due to the prevailing south-westerly winds. Manchester and Glasgow, for example, receive around double the rainfall of Sheffield and Edinburgh respectively (although there are no mountains between Edinburgh and Glasgow). The contrast is even stronger further north, where Aberdeen gets around a third of the rainfall of Fort William or Skye. In Devon, rainfall at Princetown on Dartmoor is almost three times the amount received 48 kilometres (30 mi) to the east at locations such as Exeter and Teignmouth. The Fens of East Anglia receive similar rainfall amounts to Seville.[7]

- Iceland has plenty of microclimates courtesy of the mountainous terrain. Akureyri on a northerly fiord receives about a third of the precipitation that the island of Vestmannaeyjar off the south coast gets. The smaller island is in the pathway of Gulf Stream rain fronts with mountains lining the southern coast of the mainland.

- The Scandinavian Mountains create a rain shadow for lowland areas east of the mountain chain and prevents the Oceanic climate from penetrating further east; thus Bergen and a place like Brekke in Sogn, west of the mountains, receive an annual precipitation of 2,250 millimetres (89 in) and 3,575 millimetres (141 in), respectively,[8] while Oslo receives only 760 millimetres (30 in), and Skjåk, a municipality situated in a deep valley, receives only 280 millimetres (11 in). Further east, the partial influence of the Scandinavian Mountains contribute to areas in east-central Sweden around Stockholm only receiving 550 millimetres (22 in) annually. In the north, the mountain range extending to the coast in around Narvik and Tromsø cause a lot higher precipitation there than in coastal areas further east facing north such as Alta or inland areas like Kiruna across the Swedish border.

- The South Swedish highlands, although not rising more than 377 metres (1,237 ft), reduce precipitation and increase summer temperatures on the eastern side. Combined with the high pressure of the Baltic Sea, this leads to some of the driest climates in the humid zones of Northern Europe being found in the triangle between the coastal areas in the counties of Kalmar, Östergötland and Södermanland along with the offshore island of Gotland on the leeward side of the slopes. Coastal areas in this part of Sweden usually receive less precipitation than windward locations in Andalusia in the south of Spain.[9]

Southern Europe

- The Cantabrian Mountains form a sharp divide between "Green Spain" to the north and the dry central plateau. The northern-facing slopes receive heavy rainfall from the Bay of Biscay, but the southern slopes are in rain shadow. The other most evident effect on the Iberian Peninsula occurs in the Almería, Murcia and Alicante areas, each with an average rainfall of 300 mm, which are the driest spots in Europe (see Cabo de Gata) mostly a result of the mountain range running through their western side, which blocks the westerlies.

- The Norte Region in Portugal has extreme differences in precipitation with values surpassing 3,000 mm (120 in) in the Peneda-Gerês National Park to values close to 500 mm (20 in) in the Douro Valley. Despite being only 28 km (17 mi) apart, Chaves has less than half the precipitation of Montalegre.[10]

- The eastern part of the Pyrenean mountains in the south of France (Cerdagne).

- In the Northern Apennines of Italy, Mediterranean city La Spezia receives twice the rainfall of Adriatic city Rimini on the eastern side. This is also extended to the southern end of the Apennines that see vast rainfall differences between Naples with above 1,000 millimetres (39 in) on the Mediterranean side and Bari with about 560 millimetres (22 in) on the Adriatic side.

- The valley of the Vardar River and south from Skopje to Athens is in the rain shadow of the Prokletije and Pindus Mountains. On its windward side the Prokletije has the highest rainfall in Europe at around 5,000 millimetres (200 in) with small glaciers even at mean annual temperatures well above 0 °C (32 °F), but the leeward side receives as little as 400 millimetres (16 in).

Caribbean

- Throughout the Greater Antilles, the southwestern sides are in the rain shadow of the trade winds and can receive as little as 400 millimetres (16 in) per year as against over 2,000 millimetres (79 in) on the northeastern, windward sides and over 5,000 millimetres (200 in) over some highland areas. This is most apparent in Cuba, where this phenomenon leads to the Cuban cactus scrub ecoregion, and the island of Hispaniola (which contains the Caribbean's highest mountain ranges), which results in xeric semi-arid shrublands throughout the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

Northern America

- On the largest scale, the entirety of the North American Interior Plains are shielded from the prevailing Westerlies carrying moist Pacific weather by the North American Cordillera. More pronounced effects are observed, however, in particular valley regions within the Cordillera, in the direct lee of specific mountain ranges. Most rainshadows in the western United States are due to the Sierra Nevada and Cascades ranges.[11]

- The deserts of the Basin and Range Province in the United States and Mexico, which includes the dry areas east of the Cascade Mountains of Oregon and Washington and the Great Basin, which covers almost all of Nevada and parts of Utah are rain shadowed.[12]

- The Cascades also cause rain shadowed Columbia Basin area of Eastern Washington and valleys in British Columbia, Canada - most notably the Thompson and Nicola Valleys which can receive less than 250 millimetres (10 in) of rain in parts, and the Okanagan Valley (particularly the south, nearest to the US border) which receives anywhere from 12-17 inches of rain annually.[13][14]

- The Dungeness Valley around Sequim and Port Angeles, Washington lies in the rain shadow of the Olympic Mountains. The area averages 10–15 inches of rain per year. The rain shadow extends to the eastern Olympic Peninsula, Whidbey Island, parts of the San Juan Islands, and Victoria, British Columbia which receive between 18-24 inches of precipitation each year. Seattle is also affected by the rain shadow, albeit to a much lesser effect.[15] By contrast, Aberdeen, which is situated southwest of the Olympics, receives nearly 85 inches of rain per year[16]

- The east slopes of the Coast Ranges in central and southern California also cut off the southern San Joaquin Valley from enough precipitation to ensure desert-like conditions in areas around Bakersfield.

- San Jose, and adjacent cities are usually drier than the rest of the San Francisco Bay Area because of the rain shadow cast by the highest part of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

- The Mojave, Black Rock, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan deserts all are in regions which are rain shadowed.

- The Owens Valley in the United States, behind the Sierra Nevada range in California.

- Death Valley in the United States, behind both the Pacific Coast Ranges of California and the Sierra Nevada range, is the driest place in North America and one of the driest places on the planet. This is also due to its location well below sea level which tends to cause high pressure and dry conditions to dominate due to the greater weight of the atmosphere above.

- The Colorado Front Range is limited to precipitation that crosses over the Continental Divide. While many locations west of the Divide may receive as much as 1,000 millimetres (40 in) of precipitation per year, some places on the eastern side, notably the cities of Denver and Pueblo, Colorado, typically receive only about 12 to 19 inches. Thus, the Continental Divide acts as a barrier for precipitation. This effect applies only to storms traveling west-to-east. When low pressure systems skirt the Rocky Mountains and approach from the south, they can generate high precipitation on the eastern side and little or none on the western slope.

- The Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, wedged between the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians and the Blue Ridge Mountains and partially shielded from moisture from the west and southeast, is much drier than the very humid remainder of Virginia and the American Southeast.[17]

- Asheville, North Carolina sits in the rain shadow of the Balsam, Smoky, and Blue Ridge Mountains. While the mountains surrounding Asheville contain the Appalachian Temperate Rainforests, with areas receiving over an annual average precipitation of 2,500 millimetres (100 in) , the city itself is the driest location in North Carolina, with an annual average precipitation of only 940 millimetres (37 in) .[18][19][20]

- Ashcroft, British Columbia, the only true desert in Canada, sits in the rain shadow of the Coast Mountains of Canada.[21]

- Yellowknife, the capital and most populous city in the Northwest Territories of Canada, is located in the rain shadow of the mountain ranges to the west of the city.

Australia

- In New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, Monaro is shielded by both the Snowy Mountains to the northwest and coastal ranges to the southeast. Consequently, parts of it are as dry as the wheat-growing lands of those states. For comparison, Cooma receives 535 millimetres (21.1 in) of rain annually, whereas Batlow, on the western side of the ranges, receives 1,220 millimetres (48 in) of precipitation. Furthermore, Australia's capital Canberra is also protected from the west by the Brindabellas which create a strong rain shadow in Canberra's valleys, where it receives an annual rainfall of 580 millimetres (23 in), compared to Adjungbilly's 1,075 millimetres (42.3 in). In the cool season, the Great Dividing Range also shields much of the southeast coast (i.e. Sydney, the Central Coast, the Hunter Valley, Illawarra, the South Coast) from south-westerly polar blasts that originate from the Southern Ocean.[22][23]

- In Queensland, the land west of Atherton Tableland in the Tablelands Region lies on a rain shadow and therefore would feature significantly lower annual rainfall averages than those in the Cairns Region. For comparison, Tully, which is on the eastern side of the tablelands, towards the coast, receives annual rainfall that exceeds 4,000 millimetres (160 in), whereas Mareeba, which lies on the rain shadow of the Atherton Tableland, receives 870 millimetres (34 in) of rainfall annually.

- In Tasmania, one of the states of Australia, the central Midlands region is in a strong rain shadow and receives only about a fifth as much rainfall as the highlands to the west.

- In Victoria, the western side of Port Phillip Bay is in the rain shadow of the Otway Ranges. The area between Geelong and Werribee is the driest part of southern Victoria: the crest of the Otway Ranges receives 2,000 millimetres (79 in) of rain per year and has myrtle beech rainforests much further west than anywhere else, whilst the area around Little River receives as little as 425 millimetres (16.7 in) annually, which is as little as Nhill or Longreach and supports only grassland. Also in Victoria, Omeo is shielded by the surrounding Victorian Alps, where it receives around 650 millimetres (26 in) of annual rain, whereas other places nearby exceed 1,000 millimetres (39 in).

- Western Australia's Wheatbelt and Great Southern regions are shielded by the Darling Range to the west: Mandurah, near the coast, receives about 700 millimetres (28 in) annually. Dwellingup, 40 km inland and in the heart of the ranges, receives over 1,000 millimetres (39 in) a year while Narrogin, 130 kilometres (81 mi) further east, receives less than 500 millimetres (20 in) a year.

Pacific Islands

- Hawaii also has rain shadows, with some areas being desert.[24] Orographic lifting produces the world's second-highest annual precipitation record, 12.7 meters (500 inches), on the island of Kauai; the leeward side is understandably rain-shadowed.[1] The entire island of Kahoolawe lies in the rain shadow of Maui's East Maui Volcano.

- New Caledonia lies astride the Tropic of Capricorn, between 19° and 23° south latitude. The climate of the islands is tropical, and rainfall is brought by trade winds from the east. The western side of the Grande Terre lies in the rain shadow of the central mountains, and rainfall averages are significantly lower.

- In the South Island of New Zealand is to be found one of the most remarkable rain shadows anywhere on Earth. The Southern Alps intercept moisture coming off the Tasman Sea, precipitating about 6,300 mm (250 in) to 8,900 mm (350 in) liquid water equivalent per year and creating large glaciers on the western side. To the east of the Southern Alps, scarcely 50 km (30 mi) from the snowy peaks, yearly rainfall drops to less than 760 mm (30 in) and some areas less than 380 mm (15 in). (see Nor'west arch for more on this subject).

South America

- The Atacama Desert in Chile is the driest non-polar desert on Earth because it is blocked from moisture on both sides (the Andes Mountains to the east block moist Amazon basin air while the Chilean Coast Range stops the oceanic influence from coming in from the west).

- Cuyo and Eastern Patagonia is rain shadowed from the prevailing westerly winds by the Andes range and is arid. The aridity of the lands next to eastern piedmont of the Andes decreases to the south due to a decrease in the height of the Andes with the consequence that the Patagonian Desert develop more fully at the Atlantic coast contributing to shaping the climatic pattern known as the Arid Diagonal.[25] The Argentinian wine region of Cuyo and Northern Patagonia is almost completely dependent on irrigation, using water drawn from the many rivers that drain glacial ice from the Andes.

- The Guajira Peninsula in northern Colombia is in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and despite its tropical latitude is almost arid, receiving almost no rainfall for seven to eight months of the year and being incapable of cultivation without irrigation.

References

- Whiteman, C. David (2000). Mountain Meteorology: Fundamentals and Applications. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513271-8.

- Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "trade winds". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "westerlies". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "roaring forties". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- "Asti weather". weatherbase.com.

- S.A, Wirtualna Polska Media (2016-02-02). "Kujawy - najsuchsze miejsce w Polsce". turystyka.wp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- "UK Rainfall averages". Archived from the original on 2010-02-18.

- "Spør meteorologen!". www.miljolare.no. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- "Dataserier med normalvärden för perioden 1991-2020" [Data series with normals for the period 1991-2020] (in Swedish). Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- "Iberian Climatic Atlas" (PDF). IPMA, AEMET. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- "How mountains influence rainfall patterns". USA Today. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- Chris Johnson; Matthew D. Affolter; Paul Inkenbrandt; Cam Mosher. "Deserts". An Introduction to Geology.

- Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Westerlies". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- Sue Ferguson (2001-09-07). "Climatology of the Interior Columbia River Basin" (PDF). Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- John Metcalfe (14 October 2015). "The Wet and Slightly Less Wet Microclimates of Seattle". Bllomberg News.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Aberdeen, WA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 17, 2023..

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-03. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Precipitation Variability | Western North Carolina Vitality Index".

- "Answer Man: Asheville a 'temperate rainforest' in wake of record rain?".

- "Gorges State Park | NC State Parks".

- "Canada's only desert is in B.C. But not where you think it is".

- Rain Shadows by Don White. Australian Weather News. Willy Weather. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- And the outlook for winter is … wet by Kate Doyle from The New Daily. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Giambelluca, Tom; Sanderson, Marie (1993). Prevailing Trade Winds: Climate and Weather in Hawaií. University of Hawaii Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8248-1491-5.

- Bruniard, Enrique D. (1982). "La diagonal árida Argentina: un límite climático real". Revista Geográfica (in Spanish): 5–20.