Randolph, Oregon

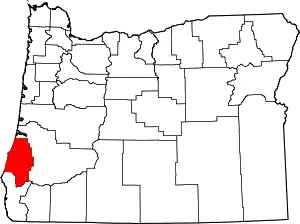

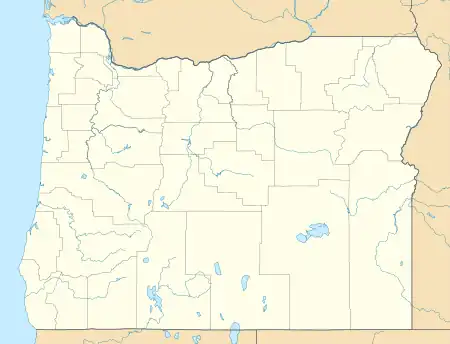

Randolph is an unincorporated community in Coos County, Oregon, United States, founded as a "black sand" gold mining boomtown in the 1850s.[1][2] Although it is considered a ghost town because there are no significant structures left at the site, the USGS classifies Randolph as a populated place.[1][3] It is on the north bank the Coquille River about 7 miles (11 km) north of Bandon and about 3 miles east of the Pacific Ocean.[4]

Randolph, Oregon | |

|---|---|

Randolph  Randolph | |

| Coordinates: 43°10′04″N 124°21′23″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Coos |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 1158438[1] |

| Coordinates and elevation from Geographic Names Information System | |

History

The community was established during a brief gold rush in Coos County by a Doctor Foster and a Captain Harris.[5] According to History of Southern Oregon (1884), they named the place after John Randolph of Roanoke, a Virginia politician.[6] However, an article published by the Oregon Historical Society in 1957 suggests two other possibilities: that it was named for Randolph, Massachusetts, or for one of the founders of Port Orford, Oregon, Randolph Tichenor.[7]

The site was first located several miles northwest of its current location, near the confluence of Whisky Run–a small stream–and the ocean.[5] The sands at this location were mined between 1853 and 1855.[5] A legend states that two miners buried a five-gallon can of gold dust under a tree in those days, but when they returned a forest fire had swept through the area, so they were unable to locate the gold, which has never been found.[8][9] The locale was originally named Whisky Run, and at one time it had the largest population of any gold camp on the coast, even approaching that of Jacksonville.[3]

Whisky Run was established in close proximity to an existing village of Coquille people known as the Nasomah tribe. Relations between the large group of miners and the small group of Nasomah grew increasingly tense after a series of sexual assaults on Coquille women and a verbal altercation at the Randolph Ferry over the Coquille River. In 1854, about 40 miners formed an anti-Coquille vigilante group, the Coos County Volunteers. Claiming that the Coquille had committed misdeeds such as riding a horse without permission, the Volunteers attacked the Nasomahs as they slept and killed about 20 of them. Joel Palmer, the Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs, responded to the massacre by persuading the remaining Coquilles to sign a treaty surrendering ownership of their homeland of about 7,000,000 acres (2,800,000 ha) in 1855 and agreeing to be transported to the Coast Indian Reservation further north.[10]

A somewhat different account of relations between the Nasomah and the miners appears in Verne Bright's "Randolph: Ghost Gold Town of the Oregon Beaches". In this account, some of the mutual antagonism stemmed from a fight in 1851 in which the Nasomah attacked twelve white men traveling along the Coquille River by canoe, killing eight of them. This incident, Bright says, was preceded by two decades during which white sailors and settlers infected many Nasomah and other Tututni with Old World diseases, usurped their hunting and fishing grounds, and generally treated them with cruel disrespect. After the 1851 fight, "The "Indians pillaged and murdered at intervals during the months that followed, and Randolph's earliest miners worked in the shadow of continued peril." For their part, the miners retaliated by summarily hanging or shooting Indians accused of theft. These acts of violence and related fears culminated in the formation of what Bright refers to as the Randolph Minute Men, who attacked the defiant Nasomah at night, killing sixteen, wounding four, taking "two score women, children, and old men" prisoner, and burning the Nasomah village. Violence continued at a reduced level until the removal of most of the remaining Indians to the Coast Reservation.[7]

Whisky Run was later moved to the mouth of the Coquille River, and after the gold rush subsided, it was moved inland to its current location.[3] A trail, originally established by the Coquille people, ran from the original site of Randolph to Empire.[2] Randolph post office opened in 1859 and ran until 1893.[5]

Further reading

- Wells, William V. (October 1856). "Wild Life in Oregon". Harper's New Monthly Magazine: 595.

References

- "Randolph". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- "Part 2. Historical Accounts, 1826 - 1875: 4. The Randolph Trail & Seven Devils: 1853 - 1857". Coquelle Trails: Early Historical Roads and Trails of Ancestral Coquille Indian Lands, 1826 - 1875. Oregon Websites and Watersheds Project. Inc. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- Friedman, Ralph (1990). In Search of Western Oregon. Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers, Ltd. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-0-87004-332-1.

- Oregon Atlas & Gazetteer (7th ed.). Yarmouth, Maine: DeLorme. 2008. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-89933-347-2.

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. pp. 799, 1029. ISBN 978-0875952772.

- Walling, A. G., ed. (1894). History of Southern Oregon: Comprising Jackson, Josephine, Douglas, Curry and Coos Counties: Compiled from the Most Authentic Sources. Portland, Oregon: A. G. Walling. p. 492. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- Bright, Verne (December 1957). "Randolph: Ghost Gold Town of the Oregon Beaches". Oregon Historical Quarterly. Oregon Historical Society. 58 (4): 293–306. JSTOR 20612359.

- Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Oregon (1940). Oregon: End of the Trail. American Guide Series. Portland, Oregon: Binfords & Mort. p. 85. OCLC 4874569.

- Friedman, Ralph (1978). "The Seasons of Randolph". Tracking Down Oregon. Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers, Ltd. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-0-87004-257-7.

- Younker, Jason. "Nasomah Massacre of 1854". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University and the Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved January 2, 2017.