Rayonnant

In French Gothic architecture, the Rayonnant (French pronunciation: [ʁɛjɔnɑ̃]) style is the third of the four phases of Gothic architecture in France, as defined by French scholars.[1][2] Related to the English division of Continental Gothic into three phases (Early, High, Late Gothic), it is the second and larger part of High Gothic.

Prominent features of Rayonnant include development of the rose window; more windows in the upper-level clerestory; the reduction of the importance of the transept; and larger openings on the ground floor to establish greater communication between the central vessel and the side aisles.[3] Interior decoration increased, and the decorative motifs spread to the outside, to the facade and the buttresses utilizing great scale and spatial rationalism towards a greater concern for two-dimensional surfaces and the repetition of decorative motifs at different scales. The use of tracery gradually spread from the stained glass windows to areas of stonework, and to architectural features such as gables.[4][5]

The first building of this style was the product of the relaunch of the upper parts of the choir of the Basilica of Saint-Denis in 1231. The major example in France are the eastern parts Amiens Cathedral (since 1236) in contrast to its western parts (1200–1235) of Classic Gothic. The most prominent and accomplished French example wre the transepts of Notre Dame de Paris (begun 1250s), including the addition of the great rose windows.[4][5] The finest example of the late Rayonnant is the royal chapel in Paris, Sainte-Chapelle, in which the upper floor has the appearance of a great cage of stained glass.[4][5]

The most prominent Rayonnant building outside France may be Cologne Cathedral. Its choir was built from 1248 to 1322, the decoration accomplished and partly remodeled until 1360. After an interruption from 1528 to 1832, the Cathedral was completed in 1880. The footplan with all foundations is medieval, but many details of the western parts are creations of the 19th century.

From Medieval France, the style quickly spread to England, where French Rayonnant tracery was often incorporated into more traditional English features, such as colonettes and vault ribs.[4][5] Notable examples of Rayonnant in England include the Angel Choir of Lincoln Cathedral, and that of Exeter Cathedral (begun before 1280). The striking retrochoir of Wells Cathedral (begun before 1280), the choir of Saint Augustine at Bristol Cathedral, and Westminster Abbey are other important examples.[3]

After the mid-14th century, Rayonnant was gradually replaced by the more ornate and highly decorated Flamboyant style.

Name

The term "Rayonnant" comes from the radiating spokes of the rose windows of the major cathedrals. The largely contemporary Decorated style in England, used many ideas from French Rayonnant.[4][5]

The term was first used by the 19th-century French art historians (notably Henri Focillon and Ferdinand de Lasteyrie) to classify Gothic styles on the basis of window tracery.

Rayonnant in France

The style originated during the reign of Louis IX of France, or Saint Louis, from 1226 to 1270. During his reign, France was the wealthiest and most powerful nation in Europe. Louis was devoutly religious and was a major patron of the Catholic Church and arts. The University of Paris, or Sorbonne, was founded under his rule, as a school of theology. The major Rayonnant cathedrals had his patronage, and his royal chapel, Sainte-Chapelle, which he built to house his extensive collection of relics of the Saints, is considered one of the major landmarks of Rayonnant Gothic.[6] He also had an important influence on English Gothic; King Henry III of England was the brother-in-law of Louis, visited Paris, and had Westminster Abbey modified after 1245 following the new style. He also attended the dedication of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, and had the east end of St. Paul's Cathedral remodelled in 1258 to resemble it.[4]

Basilica of Saint-Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis, which had been the most influential initial building of Gothic style, got problems of stability in early 13th century. Therefore, the upper parts of the choir as well as the nave and the transepts were rebuilt beginning in 1231, opening up a greater amount of interior space (though altering beyond recognition some of the original Gothic features created by Suger). The walls were rebuilt with much larger windows, which opened up the upper elevation from the main arcades to the apexes of the vaults. The apse, once dark, was filled with light.[4] In this campaign, the first triforia with windows were built. This was the onset of Rayonnant Gothic.

- Basilica of Saint-Denis, relaunch since 1231

%252C_basilique_Saint-Denis%252C_abside_3.jpg.webp) Rayonnant windows of clerestory and triforium, Primary Gothic below

Rayonnant windows of clerestory and triforium, Primary Gothic below Rayonnant rose window

Rayonnant rose window

Amiens Cathedral

The construction of Amiens Cathedral had begun in 1220 with its western parts, in the more advanced version of Classic Gothic, similar to the eastern parts of Reims Cathedral, at the same time. Its builder, Bishop Evrard de Fouilly, set out to build the largest cathedral in France; one-hundred forty-five meters long, and seventy meters wide, with a surface area of 7700 square meters. The vaults are 42.5 meters high. The nave was completed by 1235.

After the necessary enlargement of the area enclosed by the city wall, in 1236, began the construction of transept and choir, which was completed between 1241 and 1269. Here, the innovations were applied, that had been initiated in the relaunch of Saint-Denis abbey church.

The western rose window was renewed in the 16th century in Flamboyant style. A close study of the tympanum in 1992 revealed traces of paint, indicating that it was entirely painted in bright colors. The original appearance is simulated today on special occasions with coloured lights.

- Amiens Cathedral

Rayonnant choir, begun in 1236, mainly 1241–1258

Rayonnant choir, begun in 1236, mainly 1241–1258 Southern transept of Amiens Cathedral: To the right the nave of Classic Gothic, to the left the Rayonnant choir

Southern transept of Amiens Cathedral: To the right the nave of Classic Gothic, to the left the Rayonnant choir Nave of Classic Gothic, before 1235; Flamboyant rose window of 15th century

Nave of Classic Gothic, before 1235; Flamboyant rose window of 15th century

Notre-Dame de Paris

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris also received a major makeover into the new style. Between 1220 and 1230, flying buttresses were constructed to replace the old wall buttresses, and to support the walls of upper level. Thirty-seven new windows were installed, each one six meters high, each with a double-arched window topped by a rose. (Twenty-five are still in place, twelve in the nave and thirteen in the choir.).[7]

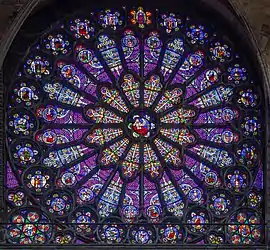

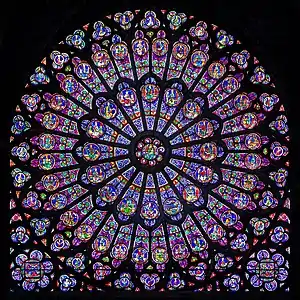

The first rose window of Notre-Dame was built on the west facade in the 1220s. In the Middle Ages, the rose was the symbol of the Virgin Mary, to whom the cathedral was dedicated.[7] The west window was smaller, with thick spokes of stone. The larger transept windows were added in about 1250 (north) and 1260 (south), with much more ornate designs and thinner mullions, or ribs, between the glass. The north window was devoted to the events of the Old Testament, and the South to the teachings of Christ and the New Testament.[7]

- Notre Dame de Paris

Rayonnant rose window of the north transept (1250s), Primary Gothic tribune windows (before 1190), one Classic Gothic clerestory (c. 1200)

Rayonnant rose window of the north transept (1250s), Primary Gothic tribune windows (before 1190), one Classic Gothic clerestory (c. 1200) North transept outside

North transept outside

Le Mans and Tours

Rayonnant spread quickly from the Ile de France to other parts of France Normandy, in many projects already under construction. At Le Mans Cathedral in Normandy, the Bishop Geoffrey de Loudon modified the plans to add double flying arches and high windows divided into lancets, as well as a circle of new Rayonnant chapels. Tours Cathedral had an even more ambitious program, financed with the assistance of Louis IX between 1236 and 1279. Its most striking Rayonnant feature was the fusion of the windows of the triforium and high clerestory windows to create a curtain of stained glass, similar to that of Sainte-Chapelle.[8]

_(13196674174).jpg.webp) Combination of the triforium and clerestory windows of Tours Cathedral (1236–1279)

Combination of the triforium and clerestory windows of Tours Cathedral (1236–1279) Triforium and Clerestory of Le Mans Cathedral (mid-13th century)

Triforium and Clerestory of Le Mans Cathedral (mid-13th century)

Sainte-Chapelle

Sainte-Chapelle, the chapel constructed by Louis IX for the relics of the Passion of Christ that he had brought back from the Crusades, consecrated in 1248, is considered the summit of the Rayonnant style. It served as a model of several similar chapels around Europe, in Aachen, Riom, and Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes at the edge of Paris. The glass was heavily coloured, the walls were brightly painted, and the portions of the walls not covered with glass were densely covered with sculpted and painted tracery.[4][5]

- Sainte-Chapelle, consecrated in 1248

Upper level

Upper level Detail sculpture

Detail sculpture

Decorated in England

An English version of the Rayonnant style began to appear in England in the middle of the 13th century. Later scholars gave the English version the term "Decorated Period". English Historians sometimes subdivide this style into two periods, based on the predominant motifs of the designs. The first, the Geometric style, lasted (about 1245 or 50 until 1315 or 1360), where ornament tended to be based on straight lines, cubes and circles, followed by the Curvilinear style (from about 1290 or 1315 until 1350 or 1360) which used gracefully curving lines.[9]

Henry III of England was the brother-in-law of Louis IX of France, and he had attended the consecration of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris in 1248. In 1245 he had begun reconstructing portions of Westminster Abbey. After his visit to Paris, he began adding Rayonnant elements. He also ordered the reconstruction of the east end of St. Paul's Cathedral, based upon the model of Sainte Chapelle. Unlike the French Rayonnant, the English version at Westminster was more heavily decorated with carved stonework.[4][5]

The style was soon used in other cathedrals and churches across England. Lincoln Cathedral saw the addition of several important Rayonnant features; the vaulted ceiling of the chapter house (1220); and the Dean's Eye rose window (1237); the Galilee Porch and the Angel Choir (1256–1280).[10] Other notable Rayonnant examples include Exeter Cathedral (begun before 1280); in the Choir of Saint Augustine at Bristol Cathedral; and in the unusual retrochoir of Wells Cathedral. In these structures, the French tracery and decoration was often mixed with typical English decorative features, including colonettes, and added very decorative ribs to the ceiling vaults.[4][5]

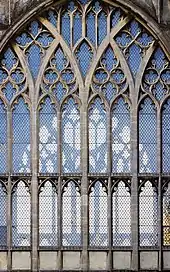

In the 14th century, the technique of grisaille was more widely used in English cathedrals, such as the nave windows of York Minster (1300–38). This was monochrome painting in large windows onto the glass, usually grey or white, which allowed more light to enter, and was usually surrounded by smaller panels of stained glass.[11]

Lierne vaulting of nave of Bristol Cathedral (1298–1382)

Lierne vaulting of nave of Bristol Cathedral (1298–1382) The Angel Choir of Lincoln Cathedral (1256–1280)

The Angel Choir of Lincoln Cathedral (1256–1280) View through retrochoir to Lady Chapel of Wells Cathedral (1329–1345)

View through retrochoir to Lady Chapel of Wells Cathedral (1329–1345) Tracery of Exeter Cathedral (after 1258)

Tracery of Exeter Cathedral (after 1258).jpg.webp) Great West window of York Minster (1338–39)

Great West window of York Minster (1338–39).jpg.webp) Grisaille in nave windows of York Minster (1330–38)

Grisaille in nave windows of York Minster (1330–38)

Central Europe

The Rayonnant style gradually spread to the east from Paris and was adapted to local styles. The nave of Strasbourg Cathedral, then in the Holy Roman Empire, was a notable early example.[3] It was begun in 1245, built atop the foundations of an earlier Romanesque church which some deviations from the usual Rayonnant arrangement of arcades, which were separated by bundled columns. The three-part elevation were large windows with lancets and roses along the aisles, more windows above on the narrow Triforium, and dramatic high windows with four lancets surmounted by quadrille windows, filling the church with light. One special aspect of the cathedral was its color; the reddish-grey stone in different shades became part of the decoration. The western façade was built in 1277. Its fine rose window of more than 13 metres diameter is divided into sixteen "soufflets", or elongated heart-shaped forms.[12] Stone of similar colour as on Strasbourg Cathedral was used for many important medieval churches in the Upper Rhine Plain. Famous examples are the cathedrals of Mainz (various Romanesque and Gothic phases) and of Worms (Late Romanesque, 1130–1181) and the minsters of Basel (Late Romanesque and Late Gothic) and of Freiburg, nave (1220–1230) and spire (finished in 1330) High Gothic.

Another important example was Cologne Cathedral. Work began in 1248 and the choir was consecrated in 1322, but work stopped in the 14th century and was not resumed until the 19th, and not finished until 1880.

The Central European examples of Rayonnant demonstrate the bias between French and German phasings; in German literature, they are called High Gothic (GE: Hochgotisch).[13]

West façade and rose window of Strasbourg Cathedral, begun in 1277

West façade and rose window of Strasbourg Cathedral, begun in 1277 Nave of Strasbourg Cathedral, begun in 1245

Nave of Strasbourg Cathedral, begun in 1245 Choir of Cologne Cathedral, begun in 1248

Choir of Cologne Cathedral, begun in 1248 Western tower of Freiburg Minster, finished in 1330

Western tower of Freiburg Minster, finished in 1330

Spain

In Spain, the Christian states of the north expanded with the success of Reconquista. They invited specialists from France, and particularly even from Germany, who made Spain participate in the actual developments north of the Pyrenees. This way, Rayonnant appeared in Spain. But each Spanish cathedral had its own very distinctive style that was difficult to classify.

Toledo Cathedral, begun in 1226 and continued in Gothic style until 1493 ,shows more preference of large windows than most other churches in Spain.

- Toledo Cathedral, begun in 1226

Elevations of Toledo Cathedral

Elevations of Toledo Cathedral Ambulatory of Toledo Cathedral

Ambulatory of Toledo Cathedral

Another important example of Rayonnant are the nave and transepts of León Cathedral, begun 1255. Other examples in Spain include Burgos cathedral, though it was much modified in the time of Flamboyant Gothic.

- León Cathedral, begun in 1255

Gerona Cathedral, begun in 1292, has triforia without windows. In Barcelona, two large churches wer built, parallelly, the cathedral 1298 to 1448 (without the facade, which was added as late as after 1882, and the central tower, added 1906–1911) and Santa Maria del Mar, 1324 to 1384. Besides some elaborate tracery in Santa Maria del Mar, both have dominant Catalonian character and little Rayonnant elements.[4] (Note: Sagrada Familia is a work of Catalan Modernisme, begun in 1882 and still not accomplished.)

Girona Cathedral, begun in 1292

Girona Cathedral, begun in 1292 The spacious nave of Girona Cathedral

The spacious nave of Girona Cathedral Santa Maria del Mar, westward

Santa Maria del Mar, westward Santa Maria del Mar, eastward

Santa Maria del Mar, eastward

Italy

In most of the Gothic architecture of Italy, transalpine forms are applied very selectively. So was the adaption of Rayonnant architecture. Some of the few examples are abbey churches whose orders were active in France and other parts of Europe. But also cathedrals have to be mentioned. The façade of Siena Cathedral was planned in the Rayonnant style, in 1284, though modified in later years. The façade is covered by fine sculpture. The interior was remodeled and vaulted in 1260 and therefore resembles northern Gothic – except of the round arcades and travers arches. Orvieto Cathedral, begun in 1290 or 1310, has many Gothic but also some Romanesque elements. It is notable for its elaborate two-dimensional decorative patterns on its façade and interiors. Its open trusses emphasize the difference from transalpine Gothic. Both interiors are dominated by polychrome marble. The facade of the bell tower 1334–1358) of Florence Cathedral is decorated with elaborate patterns in the marble, resembling Rayonnant tracery.

Upper facade of Siena Cathedral, 1215–1264

Upper facade of Siena Cathedral, 1215–1264.jpg.webp) Siena Cathedral, westward

Siena Cathedral, westward.jpg.webp) Siena Cathedral, apse and clerestory

Siena Cathedral, apse and clerestory Orvieto Cathedral, begun in 1310

Orvieto Cathedral, begun in 1310 Orvieto Cathedral, westward

Orvieto Cathedral, westward.jpg.webp) Orvieto Cathdral, traverse view

Orvieto Cathdral, traverse view

Characteristics

The distinguishing features of Rayonnant architecture included the greatly increased amount of light in the interior, due to the enlargement of the arcades and especially the increase in the number and size of windows. In distinction from the dark triforia of Classic Gothic, Rayonnant triforia are lit by windows. This became possible by covering the aisles with roofs with own ridges, instead of lean-to roofs. Nevertheless, there was some roll back of this development, see Utrecht Cathedral (younger but with dark triforia) in relation to Cologne Cathedral.

In the layout of stained glass windows, combinations of coloured subjects and uncoloured areas made the presentations more impressive and interiors brighter. The Rayonnant period coincided with the development of the band window, in which a central strip of richly coloured stained glass is positioned between upper and lower bands of clear or frosted glass, which allowed even more light to flood in, and a comparable increase in the amount of ornament, both on the inside and the exterior. This was often achieved by very elaborate designs in the rose windows and the lace-like tracery screens on the exterior to cover the facades and elements like the buttresses.

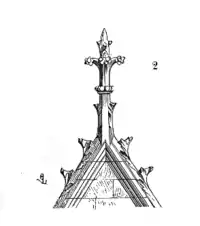

On the walls, the use of gables, pinnacles and open tracery increased.

Elevations

In early Gothic cathedrals, the walls of the nave were about equally divided between the arcades on the ground floor, the Tribune, an arcaded passage above, which buttressed the nave; above that the narrow arcaded Triforium which was a passageway which further reinforced the walls; and the clerestory on the top, just below the vaults, which usually had small windows. This changed dramatically in the Rayonnant period. Thanks to the more efficient flying buttress and quadripartite rib vaults, the walls could be higher and thinner, with more space for windows. The arcade became higher and higher, with much larger openings. The tribune, no longer needed for support, disappeared entirely. The intermediate triforium nearly disappeared, or was itself filled with windows. Most impressive was the change to the top level, the clerestory, supported by longer buttresses; the upper walls were filled with larger and larger windows, until the walls at that level nearly disappeared.[14]

The final architectural innovation that emerged as part of the Rayonnant style in France was the use of glazed triforia. Traditionally, the triforium of a Primary Gothic or Classic Gothic basilica was a dark horizontal band, usually housing a narrow passageway, that separated the top of the arcade from the clerestory. Although it made the interior darker, it was a necessary feature to accommodate the sloping lean-to roofs over the side aisles and chapels. The Rayonnant solution to this, as employed to brilliant effect in the 1230s nave of the Abbey Church of St Denis, was to use double-pitched roofs over the aisles, with hidden gutters to drain off the rainwater. This meant the outer wall of the triforioum passage could now be glazed, and the inner wall reduced to slender bar tracery. Architects also began to emphasise the linkage between triforium and clerestory by extending the central mullions from the windows of the latter in a continuous moulding running from the top of the windows down through the blind tracery of the triforium to the string course at the top of the arcading.

-Abside_et_ch%C5%93ur_adjusted.jpg.webp) Noyon Cathedral, Primary Gothic: tribune, blind triforium, windows without tracery.

Noyon Cathedral, Primary Gothic: tribune, blind triforium, windows without tracery. Choir of Chartres Cathedral, Classic Gothic: dark triforium, windows partly without tracery, partly with proto-tracery.

Choir of Chartres Cathedral, Classic Gothic: dark triforium, windows partly without tracery, partly with proto-tracery. Choir of Cologne Cathedral, Rayonnant: Above the arcades almost all is large windows with fine tracery.

Choir of Cologne Cathedral, Rayonnant: Above the arcades almost all is large windows with fine tracery.

Windows

Light, and therefore the window, was a central feature of Rayonnant architecture; Rayonnant windows were larger, more numerous, and more ornate than in earlier styles. They also frequently had clear or grisaille glass, brightening up the interior. The shadows and darkness of early Gothic cathedrals, with their small windows and deep, rich colors such as Chartres blue, was replaced by a brightly lit space with a full spectrum of coloured light.[3]

Intermediate levels of the walls, such as the Triforium, were given windows. At the high level of the clerestory, rows of lancet windows appeared, often topped with tri-lobed or four-part windows and a type of miniature rose windows, called an oculus. This was made possible at Notre-Dame by the construction of taller and longer kind of flying buttress that made a double leap to support the higher sections of the walls.

There was also a fundamental change in the tracery, or ornamental designs, within windows. Early Gothic windows often used plate-tracery (in which the window openings look as if they have been punched out of a flat stone plate. This was replaced by the more delicate bar-tracery in which the stone ribs separating the glass panels are made of narrow carved mouldings, with rounded inner and outer profiles. The elaborate designs of the spokes of the rose windows, radiating outward, gave the name to the Rayonnant style. Bar-tracery probably made its first appearance in the clerestory windows at Reims Cathedral and quickly spread across Europe.

A notable architectural innovation that emerged as part of the Rayonnant style in France was the use of glazed triforia. Traditionally, the triforium of an Early or High Gothic cathedral was a dark horizontal band, usually housing a narrow passageway, that separated the top of the arcade from the clerestory. Although it made the interior darker, it was a necessary feature to accommodate the sloping lean-to roofs over the side aisles and chapels. The Rayonnant solution to this, as employed to brilliant effect in the 1230s nave of the Abbey Church of St Denis, was to use double-pitched roofs over the aisles, with hidden gutters to drain off the rainwater. This meant the outer wall of the triforioum passage could now be glazed, and the inner wall reduced to slender bar tracery. Architects also began to emphasise the linkage between triforium and clerestory by extending the central mullions from the windows of the latter in a continuous moulding running from the top of the windows down through the blind tracery of the triforium to the string course at the top of the arcading.

In England, the Rayonnant or Decorated period was characterised by windows of great width and height, divided by mullions into subdivisions, and further elaborated with tracery. Early characteristics were a trefoil or quadrifoil design. Later windows often used an S-shaped curve, called an ogee, giving a flame-like design that heralded the Flamboyant style. Notable examples include the windows in the cloister of Westminster Abbey (1245–69), the Angel Choir of Lincoln Cathedral (1256), and the nave and west front of York Minster (1260–1320).[5]

The glazed triforium of the Abbey Church of Saint Denis (1230s)

The glazed triforium of the Abbey Church of Saint Denis (1230s)_Golden_window_crop.jpg.webp) The "Golden Window" of Wells Cathedral

The "Golden Window" of Wells Cathedral Geometric bar tracery, Ely Cathedral (1321–1351)

Geometric bar tracery, Ely Cathedral (1321–1351) Window of Lady Chapel, Ely Cathedral (1321–1351)

Window of Lady Chapel, Ely Cathedral (1321–1351) Emperor Window of Strasbourg Cathedral

Emperor Window of Strasbourg Cathedral

Rose windows

The great rose window was among the most distinctive elements of the Rayonnant. The transepts of Notre-Dame de Paris were rebuilt to make a place for two enormous rose windows, made by Jean de Chelles and Pierre de Montreuil, and paid for by King Louis IX. Similar great roses were added to the nave of the Basilica of Saint-Denis and Amiens Cathedral.[3] With the use of stone mullions separating the pieces of glass, and those glass pieces supported by lead ribs, windows became stronger and larger, able to resist strong winds. Rayonnant rose windows reached a diameter of ten meters.[15]

.jpg.webp) Plate tracery, Lincoln Cathedral "Dean's Eye" rose window (c. 1225), in French terms Classic Gothic

Plate tracery, Lincoln Cathedral "Dean's Eye" rose window (c. 1225), in French terms Classic Gothic Notre-Dame de Paris, north rose window (1250s), typically Rayonnant: the glass area exceeds the round shape of the rose structure.

Notre-Dame de Paris, north rose window (1250s), typically Rayonnant: the glass area exceeds the round shape of the rose structure.

Blind tracery

The tracery within windows inspired another form of Rayonnant decoration; the use of blind tracery, or meshes of thin ribs that could be used to cover blank walls in decorative designs, matching the designs within the windows.

Lateral choir screens of Amiens Cathedral, after 1236, pierced tracery and high relief sculpture

Lateral choir screens of Amiens Cathedral, after 1236, pierced tracery and high relief sculpture Lincoln Cathedral, Angel Choir, 2nd half of C 13, blind tracery below a dark triforium

Lincoln Cathedral, Angel Choir, 2nd half of C 13, blind tracery below a dark triforium.jpg.webp) Broederenkerk, Zutphen, blind tracery instead of lit triforia, about 1300

Broederenkerk, Zutphen, blind tracery instead of lit triforia, about 1300

Sculpture

Sculpture was an important feature of the decoration of the facades of cathedrals, a practice dating back to the Romanesque period. Stone figures of saints and the Holy family were featured on the facade and tympanum. In the Rayonnant period, the sculptures became more naturalistic and three-dimensional, standing out in their own niches across the facade. They had individual facial characteristics, natural gestures and postures, and finely-sculpted costumes. The other decorative sculpture, such as the leaves and plants that decorated the capitals of columns, also became more realistic.[5]

The sculptural decoration of Italian Gothic churches, such as the facade Orvieto Cathedral, designed by Lorenzo Maitani (1310) was extremely fine, and was part of a combination of bronze and marble figures, mosaics, and polychrome reliefs. It was a forecast of the Renaissance that was about to begin.

Naturalistic figures of Saints over west portal of Strasbourg Cathedral

Naturalistic figures of Saints over west portal of Strasbourg Cathedral Sculpture and tracery on facade of Rouen Cathedral

Sculpture and tracery on facade of Rouen Cathedral Detail of column capital sculpture, showing a farmer hitting a fruit thief Wells Cathedral

Detail of column capital sculpture, showing a farmer hitting a fruit thief Wells Cathedral Adam and Eve Sculpture on facade of Orvieto Cathedral by Lorenzo Maitani, (begun 1310)

Adam and Eve Sculpture on facade of Orvieto Cathedral by Lorenzo Maitani, (begun 1310)

Decorative elements

One distinctive element of Rayonnant was the use of carved stone decorative elements on the exterior and interior. These included the fleuron, the pinnacle, and the finial, which gave greater height to everything from doorways to buttress. These elements usually also had a practical purpose; they were often added to external structures, such as buttresses, to give them additional weight.[16]

These elements included the crocket, in the form of a stylized carving of curled leaves, buds or flowers which are used at regular intervals to decorate the sloping edges of spires, finials, pinnacles, and wimpergs.[17]

13th century Fleuron illustrated by Viollet-le-Duc

13th century Fleuron illustrated by Viollet-le-Duc_%C3%89glise_Notre-Dame_Fa%C3%A7ade_sud_01.JPG.webp) Crockets on the spire of the church of Notre-Dame de Vitré, Brussels (35)

Crockets on the spire of the church of Notre-Dame de Vitré, Brussels (35) Buttresses decorated with pinnacles, Cologne Cathedral

Buttresses decorated with pinnacles, Cologne Cathedral

Transition

The transition (in France) from Rayonnant to Flamboyant Gothic was gradual, marked primarily by a shift towards new tracery patterns based on S-shaped curves (these curves resemble flickering flames, from which the new style got its name). However, amidst the chaos of the Hundred Years War and the various other misfortunes experienced by Europe during the 14th century, relatively little large-scale construction occurred and certain elements of the Rayonnant style remained in vogue well into the next century.

See also

Notes and citations

- Dominique Vermand, site Églises de l'Oise, presentation of Beauvais Cathedral – with a didactic timetable of French architecture

- L'Histoire, L'art gothique à la conquête de l'Europe

- "Gothique". Encyclopédie Larousse (in French) (online ed.). Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Rayonnant Style at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Gothic art at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Louis IX". Encyclopédie Larousse (in French) (online ed.). Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Trintignac & Coloni 1984, p. 34-41.

- Mignon 2015, p. 32.

- Smith, A. Freeman, English Church Architecture of the Middle Ages (1922), pp. 45–47

- "Timeline - Lincoln Cathedral". Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- stained glass at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Mignon 2015, p. 40.

- Wilfried Koch, Baustilkunde, 33rd eddition (2016), Prestel Verlag, ISBN 978-3-7913-4997-8, p. 170. On the same page, for France the French criteria for Classic Gothic are applied for "Hochgotik", which pretends an immense delay of German Gothic architecture.

- Renault & Lazé 2006, p. 36.

- Ducher 2014, p. 46.

- Ducher 2014, p. 52-56.

- Crocket at the Encyclopædia Britannica

Bibliography

- Robert Branner, Paris and the Origins of Rayonnant Gothic Architecture down to 1240 ; The Art Bulletin, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Mar., 1962), pp. 39-51; JSTOR

- Bony, Jean (1983). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02831-9.

- Ducher, Robert (2014). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.

- Gothic Architecture, Paul Frankl (revised by Paul Crossley), Yale, 2000

- Smith, A. Freeman, English Church Architecture of the Middle Ages - an Elementary Handbook (1922), T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., London (1922) (Full text available on Project Gutenberg)

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Gisserot. ISBN 9-782877-474658.

- Trintignac, Andrei; Coloni, Marie-Jeanne (1984). Decouvrir Notre-Dame der Paris. Les Editions du Cerf. ISBN 2-204-02087-7.

- The Gothic Cathedral, Christopher Wilson, London, 1990, especially p. 120ff