Siege of Arcot

The siege of Arcot (23 September – 14 November 1751) took place at Arcot, India between forces of the British East India Company led by Robert Clive allied with Muhammad Ali Khan Wallajah and forces of Nawab of the Carnatic, Chanda Sahib, allied with the French East India Company. It was part of the Second Carnatic War.[1]

| Siege of Arcot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Carnatic War | |||||||

_(14566747909).jpg.webp) Robert Clive fires a cannon in the siege of Arcot | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

600 Carnatic Troops

|

5,000 Carnatic Troops

| ||||||

Background

In the early part of the 18th century, the Mughal Empire of India was in its last throes. The princely states of India, a few hundred in number, became more and more autonomous and independent with the reduced oversight of the vast Mughal empire. The British and French East India companies, which were present in Mughal India due to the hospitality of the Mughal emperors, were doing vibrant trade across the oceans between Mughal India and Europe.

The British East India Company represented British trading interests with factories, ports at Calcutta, Madras and Bombay on the three coasts of India. The French East India Company operated out of Pondicherry, just down the coast from Madras. Both European powers entered into agreements with local Nawabs and princely states, primarily for trade contacts but also hoping to gain influence over the territories that provided trade goods and tax revenue. As England and France were rivals in Europe, they carried on their rivalry to the new Eastern trade frontier by way of extending their support to rival Nawabs in India. The Indian princes were ambivalent toward the Europeans. As much as they appreciated the income from trade, they primarily desired the military might the Europeans could supply to tip the local balance of power in their favour.

In the Deccan proper, the Asaf Jah I (also known as Nizam-ul-Mulk) had founded a hereditary dynasty, with Hyderabad as its capital, which claimed to exercise authority over the entire South. The Carnatic – that is, the lowland tract between the central plateau and the Bay of Bengal – was ruled by the Nizam's deputy, the Nawab of Arcot. Farther to the south, a Hindu king reigned at Trichinopoly; and another Hindu kingdom had its seat at Tanjore. Inland, Mysore was rapidly developing into a third Hindu state; while everywhere lived chieftains, called palegars or naiks, in semi-independent lordship of citadels or hill-forts, representing the fief-holders of the ancient Hindu Vijayanagara Empire and many of them having maintained a practical independence since its fall in 1565.[2]

When the Nizam of the Deccan, Asaf Jah I died in 1748, the British and French supported rival claimants to the throne and the French candidate ultimately won out. In another disputed succession of the Carnatic which was ruled by the Nizam's deputy, the Nawab of Arcot. The French supported Chanda Sahib in his intrigues and military campaigns to become Nawab of Arcot. The net result of the above two important events was the British factory and port situated at Madras was surrounded by hostile territory.

Chanda Sahib, after consolidating his control of Arcot, wanted to eliminate his last major British-supported rival, Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah, who was at Trichinopoly. Chanda Sahib led a large force to besiege Trichinopoly. was supported by a handful of his own men and about 600 British troops. As the British commander did not have a reputation for inspiring confidence, British authorities in other parts of India were on the verge of writing off Trichinopoly and the entire south to the French.

Robert Clive, a one-time East India Company clerk who had served in the company's forces during the First Carnatic War, was outraged at the weak British response to French expansion. He proposed a plan to the governor at Madras, Thomas Saunders. Rather than challenge the strong Franco-Indian forces at Trichinopoly, he would strike at Arcot, Chanda Sahib's capital city, with the goal of forcing Chanda Sahib to lift the siege at Trichinopoly. Saunders agreed, but could only part with 200 of the 350 British soldiers under his command. Those 200 soldiers and a further 300 sepoys along with 3 small guns and eight European officers marched towards Arcot from Madras on 26 August 1751. On the morning of 29 August they reached Conjeeveram, which was at a distance of 42 miles (68 km) from Madras. Clives's intelligence informed him that the enemy garrison at Arcot was twice the size of his marching forces.

From Conjeeveram to Arcot is 27 miles (43 km) and the troops of Clive, in spite of a delay caused by a tremendous storm of thunder and lightning, reached Arcot in two days of forced marching. The garrison left by Chanda Sahib to defend Arcot, struck with panic at the sudden coming of the foe, at once abandoned the fort, despite their larger numbers. Clive and his forces took over the city and the fort without firing a single shot.[3]

When apprised of the loss of Arcot, Chanda Sahib immediately dispatched 4,000 of his best troops with 150 of the French, under the command of his son, Raza Sahib, to recapture it. On 23 September Raza Sahib entered the town and invested the fort with an army of 2,000 native regular troops, 5,000 irregulars, 120 Europeans, and 300 cavalry.

Preliminary stories

Arcot, a city of 100,000 at the time, quickly came under Clive's control, since he ordered that there be no looting and he returned property Chanda Sahib had confiscated to its rightful owners. He immediately began gathering supplies and fresh water, and reinforcing the city's defenses. There were only sixty days' provisions, but an ample supply of water. The Arcot fort was about a mile in circuit, with a low, unsubstantial parapet; some of its towers were in dilapidated condition and virtually useless as artillery positions. The moat was in several places fordable, and in other places completely dry. Clive's force was also reduced by disease and casualties to a mere 120 Europeans and 200 sepoys.

Chanda Sahib's garrison was encamped a few miles away, blocking the arrival of any resupply or reinforcements. Two sallies against them failed, so Clive decided on a night attack on 14 September. It was so successful the entire force scattered in fear, while Clive's men incurred no casualties. Two days later word came that Governor Saunders had sent two large cannon. Clive sent almost his entire force to escort the guns to the city, and the handful that remained drove off two night attacks, taking advantage of the darkness to disguise their low numbers.

Siege

Clive occupied the fort in the city centre, allowing Raza's troops to man taller buildings overlooking the walls. Clive attempted a sortie to drive the newcomers away, but ran into intense fire from newly occupied buildings. His attack managed to kill most of the French artillerymen, but he suffered the loss of fifteen of his British troops.

Completely surrounded, the defenders soon began to suffer. Cut off from outside water, the fort's reservoir was brackish. Food, thankfully, was not a problem. The besieging force, manning the nearest houses, shot at anyone who moved. The small defending force exhausted itself trying to maintain a patrol of the fort's wall.

"The native troops, it should be said, showed no less zeal and energy in the defence than their European comrades; and, with a fine generosity of feeling, they proposed to give that all the grain in store should be reserved for the use of the latter, who required more nourishment than Asiatics; for themselves, the liquor in which the rice was steeped would be sufficient." (pp.37–38, W.H. Davenport Adams (1894), The Makers of British India. Edinburgh: Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. ref1 ref2)

Negotiations

Back in Madras Governor Saunders scraped together a few more soldiers and received some new recruits from England. In the third week in October a force of but 130 British and 100 sepoys finally got on the way. Unfortunately for the defenders, the relief force was intercepted and forced to retreat. Late in October a battery of artillery arrived from the French base at Pondicherry and was positioned northwest of Clive's position. It soon knocked out one of Clive's large cannon and damaged another. For six days the French pounded the walls, destroying a section of wall between two dilapidated towers. The British tried to plug the gap with trenches, wooden palisades, and piled-up rubble. Another battery was set up to the southwest and created another breach.

The siege dragged its slow length along. Provisions and ammunition were on the point of exhaustion, and when the fiftieth day was reached, Clive's only hope lay in the assistance promised by Morari Rao, a Maratha chief, who had hitherto remained neutral, but, impressed by the British will, promised to come to their aid.

As the Maratha commander, Morari Rao, was collecting his pay, Raza Sahib learned of the threat. He quickly offered Clive honorable conditions and a gift if he would surrender. Knowing the Marathas were at hand and that another force was coming from Madras, Clive refused. Then Raza Sahib sent word that he would immediately storm the fort, and put every one of its defenders to the sword. Clive coldly replied that his father was a usurper, his army a rabble, and that he should think twice before he sent such cravens into a breach defended by English soldiers.

Battle

Raza Sahib resolved to venture an assault, and fixed it for 14 November, a day on which is celebrated the great Muhammadan festival of the Moharram, in memory of Hassan, the son of Wallajah. But on 13 November, a spy alerted Clive to the oncoming assault. The enemy advanced, driving before them elephants whose foreheads were armed with iron plates. It was expected that the gates would yield to the shock of those living battering-rams. But the huge beasts no sooner felt the English musket-balls, than they turned round and rushed furiously away, trampling on the multitude which had urged them forward. A raft was launched on the water which filled one part of the ditch. Clive, perceiving that the gunners at that post did not understand their business, took the management of a piece of artillery himself, and cleared the raft in a few minutes.

Where the moat was dry the assailants mounted with great boldness, but the British fire was heavy and well directed that they made no progress. The rear ranks of the British kept the front ranks well supplied with a constant succession of loaded muskets, and every shot told upon the living mass below. After these desperate assaults the besiegers retired behind the ditch.

The struggle lasted about an hour. Four hundred of the assailants fell, while the defenders lost only five or six men. The besieged passed an anxious night, looking for a renewal or the attack. But when day broke the enemy were no more to be seen. Under cover of fire, Raza Sahib had raised the siege and withdrawn his army to Vellore, leaving behind several guns and a large quantity of ammunition.

Aftermath

Clive's force had achieved an amazing feat in the face of the overwhelming numerical odds against them, but in India numbers were not always the telling factor. The death of the assault commander in the final charge broke his force's spirit. Whatever the combination of circumstances that brought about Clive's victory, the siege of Arcot marked a sea change in the British experience in India. Clive's biographer Mark Bence-Jones wrote, "It may have been luck, it may have been bungling on the part of the enemy, but it created the legend of English courage and invincibility which was to carry English arms in India from one success to another".[4]

Many in southern India, including some of the attacking soldiers, joined the British company's army. When the British began to seriously recruit and train the men from the armies and provinces they conquered, they ended up with a top-notch army of sepoys mixed with a handful of British Army units assigned to India. France lost her colonial empire ambitions, and the fall in her fortunes in India was made worse by French losses a few years later in the Seven Years' War.

References

- Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honorourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. p. 156. ISBN 9788131300343.

- Full text of "The makers of British India"

- With Clive in India, Or, the Beginnings of an Empire - G. A. Henty - Google Boeken

- Clive by Bence-Jones, page 48

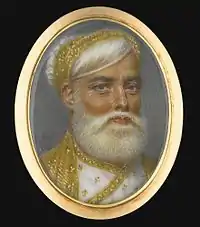

_(after)_-_Robert_Clive_(1725%E2%80%931774)%252C_Baron_Clive_of_Plassey%252C_'Clive_of_India'_-_1180787.2_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)