Rebellion

Rebellion is a violent uprising against one's government.[1] A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion.

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

Classification

An insurrection is an armed rebellion.[2]

A revolt is a rebellion with an aim to replace a government, authority figure, law, or policy.[3]

If a government does not recognize rebels as belligerents then they are insurgents and the revolt is an insurgency.[4] In a larger conflict the rebels may be recognized as belligerents without their government being recognized by the established government, in which case the conflict becomes a civil war.[lower-alpha 1]

Civil resistance movements have often aimed at, and brought about, the fall of a government or head of state, and in these cases could be considered a form of rebellion. In many of these cases, the opposition movement saw itself not only as nonviolent, but also as upholding their country's constitutional system against a government that was unlawful, for example, if it had refused to acknowledge its defeat in an election. Thus the term rebel does not always capture the element in some of these movements of acting to defend the rule of law and constitutionalism.[6]

Causes

Macro approach

The following theories broadly build on the Marxist interpretation of rebellion. Rebellion is studied, in Theda Skocpol's words, by analyzing "objective relationships and conflicts among variously situated groups and nations, rather than the interests, outlooks, or ideologies of particular actors in revolutions".[7]

Marxist view

Karl Marx's analysis of revolutions sees such expression of political violence not as anomic, episodic outbursts of discontents but rather the symptomatic expression of a particular set of objective but fundamentally contradicting class-based relations of power. The central tenet of Marxist philosophy, as expressed in Das Kapital, is the analysis of society's mode of production (societal organization of technology and labor) and the relationships between people and their material conditions. Marx writes about "the hidden structure of society" that must be elucidated through an examination of "the direct relationship of the owners of the conditions of production to the direct producers". The conflict that arises from producers being dispossessed of the means of production, and therefore subject to the possessors who may appropriate their products, is at the origin of the revolution.[8] The inner imbalance within these modes of production is derived from the conflicting modes of organization, such as capitalism emerging within feudalism, or more contemporarily socialism arising within capitalism. The dynamics engineered by these class frictions help class consciousness root itself in the collective imaginary. For example, the development of the bourgeoisie class went from an oppressed merchant class to urban independence, eventually gaining enough power to represent the state as a whole. Social movements, thus, are determined by an exogenous set of circumstances. The proletariat must also, according to Marx, go through the same process of self-determination which can only be achieved by friction against the bourgeoisie. In Marx's theory, revolutions are the "locomotives of history" because revolution ultimately leads to the overthrow of a parasitic ruling class and its antiquated mode of production. Later, rebellion attempts to replace it with a new system of political economy, one that is better suited to the new ruling class, thus enabling societal progress. The cycle of revolution, thus, replaces one mode of production with another through the constant class friction.[9]

Ted Gurr: Roots of political violence

In his book Why Men Rebel, Ted Gurr looks at the roots of political violence itself applied to a rebellion framework. He defines political violence as: "all collective attacks within a political community against the political regime, its actors [...] or its policies. The concept represents a set of events, a common property of which is the actual or threatened use of violence".[10] Gurr sees in violence a voice of anger that manifests itself against the established order. More precisely, individuals become angry when they feel what Gurr labels as relative deprivation, meaning the feeling of getting less than one is entitled to. He labels it formally as the "perceived discrepancy between value expectations and value capabilities".[11] Gurr differentiates between three types of relative deprivation:

- Decremental deprivation: one's capacities decrease when expectations remain high. One example of this is the proliferation and thus depreciation of the value of higher education.[12]

- Aspirational Deprivation: one's capacities stay the same when expectations rise. An example would be a first-generation college student lacking the contacts and network to obtain a higher paying job while watching her better-prepared colleagues bypass her.[13]

- Progressive deprivation: expectation and capabilities increase but the former cannot keep up. A good example would be an automotive worker being increasingly marginalized by the automatization of the assembly line.[14]

Anger is thus comparative. One of his key insights is that "The potential for collective violence varies strongly with the intensity and scope of relative deprivation among members of a collectivity".[15] This means that different individuals within society will have different propensities to rebel based on the particular internalization of their situation. As such, Gurr differentiates between three types of political violence:[16]

- Turmoil when only the mass population encounters relative deprivation;

- Conspiracy when the population but especially the elite encounters relative deprivation;

- Internal War, which includes revolution. In this case, the degree of organization is much higher than turmoil, and the revolution is intrinsically spread to all sections of society, unlike the conspiracy.

Charles Tilly: Centrality of collective action

In From Mobilization to Revolution, Charles Tilly argues that political violence is a normal and endogenous reaction to competition for power between different groups within society. "Collective violence", Tilly writes, "is the product of just normal processes of competition among groups in order to obtain the power and implicitly to fulfill their desires".[17] He proposes two models to analyze political violence:

- The polity model takes into account government and groups jockeying for control over power. Thus, both the organizations holding power and the ones challenging them are included.[18] Tilly labels those two groups "members" and "challengers".

- The mobilization model aims to describe the behavior of one single party to the political struggle for power. Tilly further divides the model into two sub-categories, one that deals with the internal dynamics of the group, and the other that is concerned with the "external relations" of the entity with other organizations and/or the government. According to Tilly, the cohesiveness of a group mainly relies on the strength of common interests and the degree of organization. Thus, to answer Gurr, anger alone does not automatically create political violence. Political action is contingent on the capacity to organize and unite. It is far from irrational and spontaneous.

Revolutions are included in this theory, although they remain for Tilly particularly extreme since the challenger(s) aim for nothing less than full control over power.[19] The "revolutionary moment occurs when the population needs to choose to obey either the government or an alternative body who is engaged with the government in a zero-sum game. This is what Tilly calls "multiple sovereignty".[20] The success of a revolutionary movement hinges on "the formation of coalitions between members of the polity and the contenders advancing exclusive alternative claims to control over Government.".[20]

Chalmers Johnson and societal values

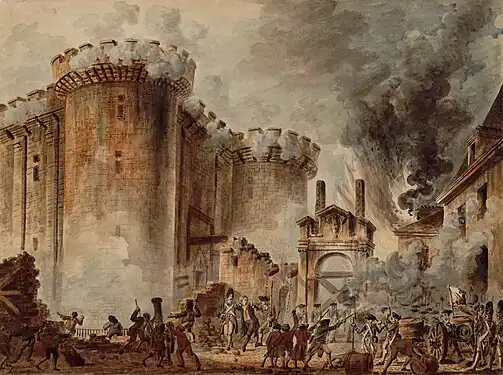

For Chalmers Johnson, rebellions are not so much the product of political violence or collective action but in "the analysis of viable, functioning societies".[21] In a quasi-biological manner, Johnson sees revolutions as symptoms of pathologies within the societal fabric. A healthy society, meaning a "value-coordinated social system"[22] does not experience political violence. Johnson's equilibrium is at the intersection between the need for society to adapt to changes but at the same time firmly grounded in selective fundamental values. The legitimacy of political order, he posits, relies exclusively on its compliance with these societal values and in its capacity to integrate and adapt to any change. Rigidity is, in other words, inadmissible. Johnson writes "to make a revolution is to accept violence for the purpose of causing the system to change; more exactly, it is the purposive implementation of a strategy of violence in order to effect a change in social structure".[23] The aim of a revolution is to re-align a political order on new societal values introduced by an externality that the system itself has not been able to process. Rebellions automatically must face a certain amount of coercion because by becoming "de-synchronized", the now illegitimate political order will have to use coercion to maintain its position. A simplified example would be the French Revolution when the Parisian Bourgeoisie did not recognize the core values and outlook of the King as synchronized with its own orientations. More than the King itself, what really sparked the violence was the uncompromising intransigence of the ruling class. Johnson emphasizes "the necessity of investigating a system's value structure and its problems in order to conceptualize the revolutionary situation in any meaningful way".[24]

Theda Skocpol and the autonomy of the state

Skocpol introduces the concept of the social revolution, to be contrasted with a political revolution. While the latter aims to change the polity, the former is "rapid, basic transformations of a society's state and class structures; and they are accompanied and in part carried through by class-based revolts from below".[25] Social revolutions are a grassroots movement by nature because they do more than change the modalities of power, they aim to transform the fundamental social structure of society. As a corollary, this means that some "revolutions" may cosmetically change the organization of the monopoly over power without engineering any true change in the social fabric of society. Her analysis is limited to studying the French, Russian, and Chinese revolutions. Skocpol identifies three stages of the revolution in these cases (which she believes can be extrapolated and generalized), each accordingly accompanied by specific structural factors which in turn influence the social results of the political action.

- The Collapse of the Old-Regime State: this is an automatic consequence of certain structural conditions. She highlights the importance of international military and economic competition as well as the pressure of the misfunctioning of domestic affairs. More precisely, she sees the breakdown of the governing structures of society influenced by two theoretical actors, the "landed upper class" and the "imperial state".[26] Both could be considered as "partners in exploitation" but in reality competed for resources: the state (monarchs) seek to build up military and economic power to ascertain their geopolitical influence. The upper class works in a logic of profit maximization, meaning preventing as much as possible the state to extract resources. All three revolutions occurred, Skocpol argues, because states failed to be able to "mobilize extraordinary resources from the society and implement in the process reforms requiring structural transformations".[27] The apparently contradicting policies were mandated by a unique set of geopolitical competition and modernization. "Revolutionary political crises occurred because of the unsuccessful attempts of the Bourbon, Romanov, and Manchu regimes to cope with foreign pressures."[27] Skocpol further concludes "the upshot was the disintegration of centralized administrative and military machinery that had theretofore provided the solely unified bulwark of social and political order".[28]

- Peasant Uprisings: more than simply a challenge by the landed upper class in a difficult context, the state needs to be challenged by mass peasant uprisings in order to fall. These uprisings must be aimed not at the political structures per se but at the upper class itself so that the political revolution becomes a social one as well. Skocpol quotes Barrington Moore who famously wrote: "peasants [...] provided the dynamite to bring down the old building".[29] Peasant uprisings are more effective depending on two given structural socioeconomic conditions: the level of autonomy (from both an economic and political point of view) peasant communities enjoy, and the degree of direct control the upper class on local politics. In other words, peasants must be able to have some degree of agency in order to be able to rebel. If the coercive structures of the state and/or the landowners keep a very close check on peasant activity, then there is no space to foment dissent.

- Societal Transformation: this is the third and decisive step after the state organization has been seriously weakened and peasant revolts become widespread against landlords. The paradox of the three revolutions Skocpol studies is that stronger centralized and bureaucratic states emerge after the revolts.[30] The exact parameters depend, again, on structural factors as opposed to voluntarist factors: in Russia, the new state found most support in the industrial base, rooting itself in cities. In China, most of the support for the revolt had been in the countryside, thus the new polity was grounded in rural areas. In France, the peasantry was not organized enough, and the urban centers not potent enough so that the new state was not firmly grounded in anything, partially explaining its artificiality.

Here is a summary of the causes and consequences of social revolutions in these three countries, according to Skocpol:[31]

| Conditions for political crises (A) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | State of agrarian economy | International pressures | |

| France | Landed-commercial upper class has moderate influence on the absolutist monarchy via bureaucracy | Moderate growth | Moderate, pressure from England |

| Russia | Landed nobility has no influence in absolutist state | Extensive growth, geographically unbalanced | Extreme, string of defeats culminating with World War I |

| China | Landed-commercial upper class has moderate influence on absolutist state via bureaucracy | Slow growth | Strong, imperialist intrusions |

| Conditions for peasant insurrections (B) | |||

| Organization of agrarian communities | Autonomy of agrarian communities | ||

| France | Peasants own 30–40% of the land and must pay tribute to the feudal landlord | Relatively autonomous, distant control from royal officials | |

| Russia | Peasants own 60% of the land, pay rent to landowners that are part of the community | Sovereign, supervised by the bureaucracy | |

| China | Peasants own 50% of the land and pay rent to the landowners, work exclusively on small plots, no real peasant community | Landlords dominate local politics under the supervision of Imperial officials | |

| Societal transformations (A + B) | |||

| France | Breakdown of absolutist state, important peasant revolts against feudal system | ||

| Russia | Failure of top-down bureaucratic reforms, eventual dissolution of the state and widespread peasant revolts against all privately owned land | ||

| China | Breakdown of absolutist state, disorganized peasant upheavals but no autonomous revolts against landowners | ||

Microfoundational evidence on causes

The following theories are all based on Mancur Olson's work in The Logic of Collective Action, a 1965 book that conceptualizes the inherent problem with an activity that has concentrated costs and diffuse benefits. In this case, the benefits of rebellion are seen as a public good, meaning one that is non-excludable and non-rivalrous.[32] Indeed, the political benefits are generally shared by all in society if a rebellion is successful, not just the individuals that have partaken in the rebellion itself. Olson thus challenges the assumption that simple interests in common are all that is necessary for collective action. In fact, he argues the "free rider" possibility, a term that means to reap the benefits without paying the price, will deter rational individuals from collective action. That is, unless there is a clear benefit, a rebellion will not happen en masse. Thus, Olson shows that "selective incentives", only made accessible to individuals participating in the collective effort, can solve the free rider problem.[33]

The Rational Peasant

Samuel L. Popkin builds on Olson's argument in The Rational Peasant: The Political Economy of Rural Society in Vietnam. His theory is based on the figure of a hyper rational peasant that bases his decision to join (or not) a rebellion uniquely on a cost-benefit analysis. This formalist view of the collective action problem stresses the importance of individual economic rationality and self-interest: a peasant, according to Popkin, will disregard the ideological dimension of a social movement and focus instead on whether or not it will bring any practical benefit to him. According to Popkin, peasant society is based on a precarious structure of economic instability. Social norms, he writes, are "malleable, renegotiated, and shifting in accord with considerations of power and strategic interaction among individuals"[34] Indeed, the constant insecurity and inherent risk to the peasant condition, due to the peculiar nature of the patron-client relationship that binds the peasant to his landowner, forces the peasant to look inwards when he has a choice to make. Popkin argues that peasants rely on their "private, family investment for their long run security and that they will be interested in short term gain vis-à-vis the village. They will attempt to improve their long-run security by moving to a position with higher income and less variance".[35] Popkin stresses this "investor logic" that one may not expect in agrarian societies, usually seen as pre-capitalist communities where traditional social and power structures prevent the accumulation of capital. Yet, the selfish determinants of collective action are, according to Popkin, a direct product of the inherent instability of peasant life. The goal of a laborer, for example, will be to move to a tenant position, then smallholder, then landlord; where there is less variance and more income. Voluntarism is thus non-existent in such communities.

Popkin singles out four variables that impact individual participation:

- Contribution to the expenditure of resources: collective action has a cost in terms of contribution, and especially if it fails (an important consideration with regards to rebellion)

- Rewards : the direct (more income) and indirect (less oppressive central state) rewards for collective action

- Marginal impact of the peasant's contribution to the success of collective action

- Leadership "viability and trust" : to what extent the resources pooled will be effectively used.

Without any moral commitment to the community, this situation will engineer free riders. Popkin argues that selective incentives are necessary to overcome this problem.[36]

Opportunity cost of rebellion

Political Scientist Christopher Blattman and World Bank economist Laura Ralston identify rebellious activity as an "occupational choice".[37] They draw a parallel between criminal activity and rebellion, arguing that the risks and potential payoffs an individual must calculate when making the decision to join such a movement remains similar between the two activities. In both cases, only a selected few reap important benefits, while most of the members of the group do not receive similar payoffs.[38] The choice to rebel is inherently linked with its opportunity cost, namely what an individual is ready to give up in order to rebel. Thus, the available options beside rebellious or criminal activity matter just as much as the rebellion itself when the individual makes the decision. Blattman and Ralston, however, recognize that "a poor person's best strategy" might be both rebellion illicit and legitimate activities at the same time.[38] Individuals, they argue, can often have a varied "portofolio" of activities, suggesting that they all operate on a rational, profit maximizing logic. The authors conclude that the best way to fight rebellion is to increase its opportunity cost, both by more enforcement but also by minimizing the potential material gains of a rebellion.[38]

Selective incentives based on group membership

The decision to join a rebellion can be based on the prestige and social status associated with membership in the rebellious group. More than material incentives for the individual, rebellions offer their members club goods, public goods that are reserved only for the members inside that group. Economist Eli Berman and Political Scientist David D. Laitin's study of radical religious groups show that the appeal of club goods can help explain individual membership. Berman and Laitin discuss suicide operations, meaning acts that have the highest cost for an individual. They find that in such a framework, the real danger to an organization is not volunteering but preventing defection. Furthermore, the decision to enroll in such high stakes organization can be rationalized.[39] Berman and Laitin show that religious organizations supplant the state when it fails to provide an acceptable quality of public goods such a public safety, basic infrastructure, access to utilities, or schooling.[40] Suicide operations "can be explained as a costly signal of "commitment" to the community".[41] They further note "Groups less adept at extracting signals of commitment (sacrifices) may not be able to consistently enforce incentive compatibility."[42] Thus, rebellious groups can organize themselves to ask of members proof of commitment to the cause. Club goods serve not so much to coax individuals into joining but to prevent defection.

Greed vs grievance model

World Bank economists Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler compare two dimensions of incentives:

- Greed rebellion: "motivated by predation of the rents from primary commodity exports, subject to an economic calculus of costs and a military survival constraint".[43]

- Grievance rebellion: "motivated by hatreds which might be intrinsic to ethnic and religious differences, or reflected objective resentments such as domination by an ethnic majority, political repression, or economic inequality".[43] The two main sources of grievance are political exclusion and inequality.

Vollier and Hoeffler find that the model based on grievance variables systematically fails to predict past conflicts, while the model based on greed performs well. The authors posit that the high cost of risk to society is not taken into account seriously by the grievance model: individuals are fundamentally risk-averse. However, they allow that conflicts create grievances, which in turn can become risk factors. Contrary to established beliefs, they also find that a multiplicity of ethnic communities make society safer, since individuals will be automatically more cautious, at the opposite of the grievance model predictions.[43] Finally, the authors also note that the grievances expressed by members of the diaspora of a community in turmoil has an important on the continuation of violence.[44] Both greed and grievance thus need to be included in the reflection.

The Moral Economy of the Peasant

Spearheaded by political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott in his book The Moral Economy of the Peasant, the moral economy school considers moral variables such as social norms, moral values, interpretation of justice, and conception of duty to the community as the prime influencers of the decision to rebel. This perspective still adheres to Olson's framework, but it considers different variables to enter the cost/benefit analysis: the individual is still believed to be rational, albeit not on material but moral grounds.[45]

Early conceptualization: E. P. Thompson and bread riots in England

British historian E.P. Thompson is often cited as being the first to use the term "moral economy", he said in his 1991 publication that the term had been in use since the 18th century.[46][47] In his 1971 Past & Present journal article, Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century, he discussed English bread riots, and other localized form of rebellion by English peasants throughout the 18th century. He said that these events have been routinely dismissed as "riotous", with the connotation of being disorganized, spontaneous, undirected, and undisciplined. He wrote that, on the contrary, such riots involved a coordinated peasant action, from the pillaging of food convoys to the seizure of grain shops. A scholar such as Popkin has argued that peasants were trying to gain material benefits, such as more food. Thompson sees a legitimization factor, meaning "a belief that [the peasants] were defending traditional rights and customs". Thompson goes on to write: "[the riots were] legitimized by the assumptions of an older moral economy, which taught the immorality of any unfair method of forcing up the price of provisions by profiteering upon the necessities of the people". In 1991, twenty years after his original publication, Thompson said that his, "object of analysis was the mentalité, or, as [he] would prefer, the political culture, the expectations, traditions, and indeed, superstitions of the working population most frequently involved in actions in the market".[46] The opposition between a traditional, paternalist, and the communitarian set of values clashing with the inverse liberal, capitalist, and market-derived ethics is central to explain rebellion.

James C. Scott and the formalization of the moral economy argument

In his 1976 book The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia, James C. Scott looks at the impact of exogenous economic and political shocks on peasant communities in Southeast Asia. Scott finds that peasants are mostly in the business of surviving and producing enough to subsist.[48] Therefore, any extractive regime needs to respect this careful equilibrium. He labels this phenomenon the "subsistence ethic".[49] A landowner operating in such communities is seen to have the moral duty to prioritize the peasant's subsistence over his constant benefit. According to Scott, the powerful colonial state accompanied by market capitalism did not respect this fundamental hidden law in peasant societies. Rebellious movements occurred as the reaction to an emotional grief, a moral outrage.[50]

Other non-material incentives

Blattman and Ralston recognize the importance of immaterial selective incentives, such as anger, outrage, and injustice ("grievance") in the roots of rebellions. These variables, they argue, are far from being irrational, as they are sometimes presented. They identify three main types of grievance arguments:

- Intrinsic incentives holds that "injustice or perceived transgression generates an intrinsic willingness to punish or seek retribution".[51] More than material rewards, individuals are naturally and automatically prompted to fight for justice if they feel they have been wronged. The ultimatum game is an excellent illustration: player one receives $10 and must split it with another player who doesn't get the chance to determine how much he receives, but only if the deal is made or not (if he refuses, everyone loses their money). Rationally, player 2 should take whatever the deal is because it is better in absolute term ($1 more remains $1 more). However, player 2 is most likely unwilling to accept less than 2 or 2 dollars, meaning that they are willing to pay a-$2 for justice to be respected. This game, according to Blattman and Ralston, represents "the expressive pleasure people gain from punishing an injustice".[51]

- Loss aversion holds that "people tend to evaluate their satisfaction relative to a reference point, and that they are 'loss adverse".[52] Individuals prefer not losing over the risky strategy of making gains. There is a substantial subjective part to this, however, as some may realize alone and decide that they are comparatively less well off than a neighbor, for example. To "fix" this gap, individuals will in turn be ready to take great risks so as to not enshrine a loss.[52]

- Frustration-aggression: this model holds that the immediate emotional reactions to highly stressful environments do not obey to any "direct utility benefit but rather a more impulsive and emotional response to a threat".[52] There are limits to this theory: violent action is to a large extent a product of goals by an individual which are in turn determined by a set of preferences.[53] Yet, this approach shows that contextual elements like economic precarity have a non-negligible impact on the conditions of the decisions to rebel at minimum.

Recruitment

Stathis N. Kalyvas, a political science professor at Yale University, argues that political violence is heavily influenced by hyperlocal socio-economic factors, from the mundane traditional family rivalries to repressed grudges.[54] Rebellion, or any sort of political violence, are not binary conflicts but must be understood as interactions between public and private identities and actions. The "convergence of local motives and supralocal imperatives" make studying and theorizing rebellion a very complex affair, at the intersection between the political and the private, the collective and the individual.[55] Kalyvas argues that we often try to group political conflicts according to two structural paradigms:

- The idea that political violence, and more specifically rebellion, is characterized by a complete breakdown of authority and an anarchic state. This is inspired by Thomas Hobbes' views. The approach sees rebellion as being motivated by greed and loot, using violence to break down the power structures of society.[54]

- The idea that all political violence is inherently motivated by an abstract group of loyalties and beliefs, "whereby the political enemy becomes a private adversary only by virtue of prior collective and impersonal enmity".[54] Violence is thus not a "man to man" affair as much as a "state to state" struggle, if not an "idea vs idea" conflict.[54]

Kalyvas' key insight is that the central vs periphery dynamic is fundamental in political conflicts. Any individual actor, Kalyvas posits, enters into a calculated alliance with the collective.[56] Rebellions thus cannot be analyzed in molar categories, nor should we assume that individuals are automatically in line with the rest of the actors simply by virtue of ideological, religious, ethnic, or class cleavage. The agency is located both within the collective and in the individual, in the universal and the local.[56] Kalyvas writes: "Alliance entails a transaction between supralocal and local actors, whereby the former supply the later with external muscle, thus allowing them to win decisive local advantage, in exchange the former rely on local conflicts to recruit and motivate supporters and obtain local control, resources, and information- even when their ideological agenda is opposed to localism".[56] Individuals will thus aim to use the rebellion in order to gain some sort of local advantage, while the collective actors will aim to gain power. Violence is a mean as opposed to a goal, according to Kalyvas.

The greater takeaway from this central/local analytical lens is that violence is not an anarchic tactic or a manipulation by an ideology, but a conversation between the two. Rebellions are "concatenations of multiple and often disparate local cleavages, more or less loosely arranged around the master cleavage".[56] Any pre-conceived explanation or theory of a conflict must not be placated on a situation, lest one will construct a reality that adapts itself to his pre-conceived idea. Kalyvas thus argues that political conflict is not always political in the sense that they cannot be reduced to a certain discourse, decisions, or ideologies from the "center" of collective action. Instead, the focus must be on "local cleavages and intracommunity dynamics".[57] Furthermore, rebellion is not "a mere mechanism that opens up the floodgates to random and anarchical private violence".[57] Rather, it is the result of a careful and precarious alliance between local motivations and collective vectors to help the individual cause.

Footnotes

- In supporting Lincoln on this issue, the Supreme Court upheld his theory of the Civil War as an insurrection against the United States government that could be suppressed according to the rules of war. In this way, the United States was able to fight the war as if it were an international war, without actually having to recognize the de jure existence of the Confederate government.[5]

References

- Lalor, John Joseph (1884). Cyclopedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political ... Rand, McNally. p. 632.

- "Insurrection". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

Insurrection: The action of rising in arms or open resistance against established authority or governmental restraint; with pl., an instance of this, an armed rising, a revolt; an incipient or limited rebellion.

- "revolt". Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- "Insurgent". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

Insurgent: One who rises in revolt against constituted authority; a rebel who is not recognized as a belligerent.

- Hall, Kermit L. (2001). The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions. U.S.: Oxford University Press. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-19-513924-0, ISBN 978-0-19-513924-2.

- Roberts, Adam; Ash, Timothy Garton, eds. (2009). Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The experience of non-violent action from Gandhi to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199552016.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 291.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 7.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 8.

- Gurr 1970, p. 3.

- Gurr 1970, p. 37.

- Gurr 1970, p. 47.

- Gurr 1970, p. 52.

- Gurr 1970, p. 53.

- Gurr 1970, p. 24.

- Gurr 1970, p. 11.

- Tilly 1978, p. 54.

- Tilly 1978, p. ch3.

- Tilly 1978, p. ch7.

- Tilly 1978, p. 213.

- Johnson 1966, p. 3.

- Johnson 1966, p. 36.

- Johnson 1966, p. 57.

- Johnson 1966, p. 32.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 4.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 49.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 50.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 51.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 112.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 162.

- Skocpol 1979, p. 155.

- Olson 1965, p. 9.

- Olson 1965, p. 76.

- Popkin 1979, p. 22.

- Popkin 1979, p. 23.

- Popkin 1979, p. 34.

- Blattman & Ralston 2015, p. 22.

- Blattman & Ralston 2015, p. 23.

- Berman & Laitin 2008, p. 1965.

- Berman & Laitin 2008, p. 1944.

- Berman & Laitin 2008, p. 1943.

- Berman & Laitin 2008, p. 1954.

- Collier & Hoeffler 2002, p. 26.

- Collier & Hoeffler 2002, p. 27.

- Scott 1976, p. 6.

- Thompson, E. P. (1991). Customs in Common: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture. The New Press. ISBN 9781565840744.

- Thompson, E. P. (1971-01-01). "The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century". Past & Present. 50 (50): 76–136. doi:10.1093/past/50.1.76. JSTOR 650244.

- Scott 1976, p. 15.

- Scott 1976, p. 13.

- Scott 1976, p. 193.

- Blattman & Ralston 2015, p. 24.

- Blattman & Ralston 2015, p. 25.

- Blattman & Ralston 2015, p. 26.

- Kalyvas 2003, p. 476.

- Kalyvas 2003, p. 475.

- Kalyvas 2003, p. 486.

- Kalyvas 2003, p. 487.

Sources

- Berman, Eli; Laitin, David (2008). "Religion, terrorism and public goods: Testing the club model" (PDF). Journal of Public Economics. 92 (10–11): 1942–1967. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.178.8147. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.03.007. S2CID 1698386.

- Blattman, Christopher; Ralston, Laura (2015). "Generating employment in Poor and Fragile States: Evidence from labor market and entrepreneurship programs". World Bank Development Impact Evaluation (DIME).

- Collier, Paul; Hoeffler, Anke (2002). Greed and Grievance in Civil War (PDF). The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Vol. 2355.

- Gurr, Ted Robert (1970). Why Men Rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691075280.

- Johnson, Chalmers (1966). Revolutionary Change. Boston: Little Brown.

- Kalyvas, Stathis N. (2003-01-01). "The Ontology of 'Political Violence': Action and Identity in Civil Wars". Perspectives on Politics. 1 (3): 475–494. doi:10.1017/s1537592703000355. JSTOR 3688707. S2CID 15205813.

- Marx, Karl (1967). Capital Vol. 3: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole. New York: International Publishers.

- Olson, Mancur (1965). The Logic of Collective Action:Public Groups and Theories of Groups. Harvard University Press.

- Popkin, Samuel L. (1979). The Rational Peasant: The Political Economy of Rural Society in Vietnam.

- Scott, James C. (November 16, 1976). The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia.

- Skocpol, Theda (1979). States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tilly, Charles (1978). From Mobilization to Revolution. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0201075717.

External links

Quotations related to Rebellion at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Rebellion at Wikiquote