Revolt of the Three Feudatories

The Revolt of the Three Feudatories, (Chinese: 三藩之亂; pinyin: Sānfān zhī luàn) also known as the Rebellion of Wu Sangui, was a rebellion in China lasting from 1673 to 1681, during the early reign of the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). The revolt was led by the three lords of the fiefdoms in Yunnan, Guangdong and Fujian provinces against the Qing central government.[1] These hereditary titles had been given to prominent Han Chinese defectors who had helped the Manchu conquer China during the transition from Ming to Qing. The feudatories were supported by Zheng Jing's Kingdom of Tungning in Taiwan, which sent forces to invade Mainland China. Additionally, minor Han military figures, such as Wang Fuchen and the Chahar Mongols, also revolted against Qing rule. After the last remaining Han resistance had been put down, the former princely titles were abolished.

| Revolt of the Three Feudatories | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

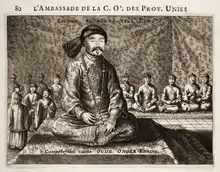

Wu Sangui (center) was one of the three rebel leaders | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

|

Wu Sangui Shang Zhixin Geng Jingzhong |

Chinggisid Chahar Mongol Zheng's Taiwan Other rebels Tiandihui | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

|

Giyesu Yolo Shang Kexi |

Wu Sangui Wu Shifan Geng Jingzhong (1674–76) Shang Zhixin(1676–79) |

Borni (Burni) Abunai Lubuzung Zheng Jing | ||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

| 400,000 |

Wu Sangui: 200,000 Shang Zhixin: 100,000 Geng Jingzhong: 200,000 |

Chahar Mongols: 10,000 Zheng Jing: 10,000 Wang Fuchen: Several thousands Sun Yanling/Kong Sizhen: 10,000 | ||||||||

Background

In the early years of the Qing Dynasty, during the reign of the Shunzhi Emperor, central government authority was not strong and the rulers were unable to control the provinces in southern China directly. The government initiated a policy of "letting the Han Chinese govern the Han Chinese" (以漢制漢). Some generals of the former Ming Dynasty who had surrendered the Qing were allowed to help govern the provinces in the south.[2]

That was the result of the crucial contributions those generals had made at decisive moments during the Qing conquest of China. For instance, the navy of Geng Zhongming and Shang Kexi brought about the quick capitulation of Joseon in 1636, allowing rapid advance into Ming territories without worrying about what was behind. The defection and subsequent cooperation of Wu Sangui allowed swift capture and settlement of the Ming capital Beijing. In return, the Qing government had to reward their achievements, and acknowledge their military and political influence.

In 1655, Wu Sangui was granted the title of "Pingxi Prince" (平西王; "West Pacifying Prince") and granted governorship of the provinces of Yunnan and Guizhou. Shang Kexi and Geng Zhongming were granted the titles of "Pingnan Prince" and "Jingnan Prince" (both mean "South Pacifying Prince") respectively, and were put in charge of the provinces of Guangdong and Fujian. The three lords had great influence over their lands and wielded far greater power than any other regional or provincial governors. They had their own military forces and had the authority to alter tax rates in their fiefs.

The Three Feudatories

In Yunnan and Guizhou, Wu Sangui was granted permission by the Shunzhi Emperor to appoint and promote his own personal group of officials, as well as the privilege of choosing warhorses first before the Qing armies. Wu Sangui's forces took up several million taels of silver in military pay, taking up a third of the Qing government's revenue from taxes. Wu was also in charge of handling the Qing government's diplomatic relationships with the Dalai Lama and Tibet. Most of Wu's troops were formerly Li Zicheng and Zhang Xianzhong's forces and they were well-versed in warfare.

In Fujian province, Geng Zhongming ruled as a tyrant over his fief, allowing his subordinates to extort food supplies and money from the common people. After Geng's death, his son Geng Jimao inherited his father's title and fiefdom, and Geng Jimao was later succeeded by his son Geng Jingzhong.[3]

In Guangdong province, Shang Kexi ruled his fief in a similar fashion to Geng Jingzhong. In total, much of the central government's revenue and reserves were spent on the Three Feudatories, and their expenditure emptied almost half of the imperial treasury. When the Kangxi Emperor came to the throne, he felt that the Three Feudatories posed a great threat to his sovereignty and wanted to reduce their power.

In 1667, Wu Sangui submitted a request to the Kangxi Emperor, asking for permission to be relieved of his duties in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces, on the premise that he was ill. Kangxi, not yet ready for a trial of strength with him, refused Wu's request.[4] In 1673, Shang Kexi asked for permission to retire,[5] and in July, Wu Sangui and Geng Jingzhong followed suit. Kangxi sought advice from his council on the issue and received divided responses. Some thought that the Three Feudatories should be left as they were, while others supported the idea of reducing the three lords' powers. Kangxi went against the views of the majority in the council and accepted the three lords' requests for retirement, ordering them to leave their respective fiefs and resettle in Manchuria.[6]

Declaring rebellion

In December 1673, Wu Sangui ended his connection to the Qing dynasty and instigated the rebellion under the banner of "opposing Qing and restoring Ming" (反清復明). Wu courted Han Chinese officials to join the rebellion by restoring Ming customs and cutting off queues.[7] Later on in 1678, he declared a new dynasty, the Zhou, invoking the name of the great pre-imperial dynasty.[8] Wu offered the Kangxi emperor clemency if he were to leave Beijing and return to the Manchu homeland.

Wu's forces captured Hunan and Sichuan provinces. In 1674 both Geng Jingzhong in Fujian and after Shang Zhixin, the man who massacred Guangzhou, died, his son followed suit in Guangdong.[9] At the same time, Sun Yanling and Wang Fuchen also rose in revolt in Guangxi and Shaanxi provinces. Zheng Jing, ruler of the Kingdom of Tungning, led an allegedly 150,000 strong army from Taiwan and landed in Guangdong, Fujian and Zhejiang to fight and join the rebel forces.

Composition of Qing armies

.jpg.webp)

The Qing forces were initially defeated by Wu in 1673–1674.[10] Manchu Generals and Bannermen were put to shame by the performance of the Han Chinese Green Standard Army, who fought better than them against the rebels. The Qing had the support of the majority of Han Chinese soldiers and the Han elite, as they did not join the Three Feudatories. Different sources offer different account of the Han and Manchu forces deployed against the rebels. According to one, 400,000 Green Standard Army soldiers and 150,000 Bannermen served on the Qing side during the war.[11] according to another, 213 Han Chinese Banner companies, and 527 companies of Mongol and Manchu Banners were mobilized by the Qing.[12] According to a third, mustered the Qing a massive army of more than 900,000 northern Han Chinese to fight the Three Feudatories.[13]

Fighting in northwestern China against Wang Fuchen, the Qing put Bannermen in the rear as reserves while they used Han Chinese Green Standard Army soldiers and Han Chinese Generals like Zhang Liangdong, Wang Jinbao, and Zhang Yong as their main military force.[14] The Qing thought that Han Chinese soldiers were superior at fighting other Han people and so used the Green Standard Army as their main army against the rebels instead of Bannermen.[15][16][17] As a result, after 1676, the tide turned in favor of the Qing forces. In the northwest, Wang Fuchen surrendered after a three-year-long stalemate, while Geng Jingzhong and Shang Zhixin surrendered in turn as their forces weakened.

Campaigning

In 1676 Shang Zhixin joined the rebellion, consolidating Guangdong under his rule and sending troops north into Jiangxi.[18]

In 1677, Wu Sangui suspected Sun Yanling would surrender to the Qing in Guangxi and he sent his relative Wu Shizong, to assassinate Sun. Sun's wife Kong Sizhen took control of his troops after his death, although she may already have had control beforehand.

In the south, Wu Sangui moved his armies north after conquering Hunan, while the Qing forces concentrated on recapturing Hunan from him. In 1678, Wu finally proclaimed himself emperor of the Great Zhou Dynasty (大周)[19] in Hengzhou (衡州; present-day Hengyang, Hunan province) and established his own imperial court. However Wu died of illness in August (lunar month) that year and was succeeded by his grandson Wu Shifan, who ordered a retreat back to Yunnan.[20] While the rebel army's morale was low, Qing forces launched an attack on Yuezhou (岳州; present-day Yueyang, Hunan province) and captured it, along with the rebel territories of Changde, Hengzhou and others. Wu Shifan's forces retreated to the Chenlong Pass. Sichuan and southern Shaanxi were retaken by the Han Chinese Green Standard Army under Wang Jinbao and Zhao Liangdong in 1680,[21] with Manchu forces involved only in dealing with logistics and provisions, not combat.[22][23] In 1680, the provinces of Hunan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and Sichuan were recovered by the Qing, and Wu Shifan retreated to Kunming in October.

In 1681, the Qing general Zhao Liangdong proposed a three-pronged attack on Yunnan, with imperial armies from Hunan, Guangxi and Sichuan. Cai Yurong, Viceroy of Yun-Gui, led the attack on the rebels together with Zhang Tai and Laita Giyesu, conquering Mount Wuhua and besieging Kunming. In October, Zhao Liandong's army was the first to break through into Kunming and the others followed suit, swiftly capturing the city. Wu Shifan committed suicide in December and the rebels surrendered the following day.[24]

Zheng Jing's forces were defeated near Xiamen in 1680 and forced to withdraw to Taiwan.[25] The final victory over the revolt was the Qing conquest of the Kingdom of Tungning on Taiwan. Shi Lang was appointed as admiral of the Qing navy and led an invasion of Taiwan, defeating the Tungning navy under Liu Guoxuan in the Battle of Penghu.[26] Zheng Jing's son Zheng Keshuang surrendered in October 1683, and Taiwan became part of the Qing Empire. Zheng Keshuang was awarded by the Kangxi Emperor with the title "Duke of Haicheng" (海澄公) and he and his soldiers were inducted into the Eight Banners.[27][28]

Aftermath

Shang Zhixin was forced to commit suicide in 1680;[29] of his thirty six brothers, four were executed when he committed suicide, while the rest of his family was allowed to live. Geng Jingzhong was executed; his brother Geng Juzhong 耿聚忠 was in Beijing with the Qing court with the Kangxi Emperor, during the rebellion, and was not punished for his brother's revolt. Geng Juzhong died of natural causes in 1687. Several Ming princes had accompanied Koxinga to Taiwan in 1661–1662, including the Prince of Ningjing, Zhu Shugui and Prince Zhu Honghuan (朱弘桓), son of Zhu Yihai. The Qing sent the 17 Ming princes still living on Taiwan back to mainland China where they spent the rest of their lives in exile since their lives were spared from execution.[30]

In 1685, the Qing used former Ming loyalist Han Chinese naval specialists who had served under the Zheng family in Taiwan in the siege of Albazin.[18][31] Former Ming loyalist Han Chinese troops who had served under Zheng Chenggong and who specialized at fighting with rattan shields and swords (Tengpaiying) 藤牌营 were recommended to the Kangxi Emperor to reinforce Albazin against the Russians. Kangxi was impressed by a demonstration of their techniques and ordered 500 of them to defend Albazin, under Ho Yu, a former Koxinga follower, and Lin Hsing-chu, a former General of Wu Sangui. These rattan shield troops did not suffer a single casualty when they defeated and cut down Russian forces traveling by rafts on the river, only using the rattan shields and swords while fighting naked.[32][33][34]

"[the Russian reinforcements were coming down to the fort on the river] Thereupon he [Marquis Lin] ordered all our marines to take off their clothes and jump into the water. Each wore a rattan shield on his head and held a huge sword in his hand. Thus they swam forward. The Russians were so frightened that they all shouted: 'Behold, the big-capped Tartars!' Since our marines were in the water, they could not use their firearms. Our sailors wore rattan shields to protect their heads so that enemy bullets and arrows could not pierce them. Our marines used long swords to cut the enemy's ankles. The Russians fell into the river, most of them either killed or wounded. The rest fled and escaped. [Lin[ Hsing-chu had not lost a single marine when he returned to take part in besieging the city.", written by Yang Hai-Chai, who was related to Marquis Lin, a participant in the war[35]

Literature

The revolt is featured in Louis Cha's novel The Deer and the Cauldron. The story tells of how the protagonist, Wei Xiaobao, helps the Kangxi Emperor suppress the rebellion.

Tsao, Kai-Fu. The Rebellion of the Three Feudatories Against the Manchu Throne in China, 1673–1681: Its Setting and Significance.

External links

References

- Michael Dillon (19 December 2013). Dictionary of Chinese History. Taylor & Francis. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-135-16681-6.

- Harold Miles Tanner (13 March 2009). China: A History. Hackett Publishing. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-87220-915-2.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1990). The Search for Modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 50. - Registration required

- Peter C Perdue (30 June 2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5.

- Qizhi Zhang (15 April 2015). An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Springer. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-662-46482-3.

- Spence, Emperor of China, p. xvii

- Spence (1990)

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Search for Modern China. W. W. Morton & Company. p. 50. ISBN 0-393-97351-4.

- Spence, Jonathan (2002). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 9. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780521243346.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- Nicola Di Cosmo (2006). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China. pp. 17.

- Nicola Di Cosmo (2006). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China. p. 23.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- Nicola Di Cosmo (2006). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-135-78955-8.

- Nicholas Belfield Dennys (1888). The China Review, Or, Notes and Queries on the Far East. "China Mail" Office. pp. 234–.

- Nicola Di Cosmo (2006). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China. pp. 24–25.

- Nicola Di Cosmo (2006). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China. p. 15.

- Jonathan D. Spence (1991). The Search for Modern China. Norton. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-0-393-30780-1.

- John Keegan; Andrew Wheatcroft (12 May 2014). Who's Who in Military History: From 1453 to the Present Day. Routledge. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-136-41409-1.

- Barbara Bennett Peterson (17 September 2016). Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century. Taylor & Francis. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-317-46372-6.

- Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo (24 January 2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-135-78955-8.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- Nicola Di Cosmo (2006). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China. p. 17.

- Nicola Di Cosmo (24 January 2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-1-135-78954-1.

- Xing Hang (5 January 2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-316-45384-1.

- Young-tsu Wong (5 August 2017). China's Conquest of Taiwan in the Seventeenth Century: Victory at Full Moon. Springer Singapore. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-981-10-2248-7.

- Herbert Baxter Adams (1925). Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science: Extra volumes. p. 57.

- Pao Chao Hsieh (23 October 2013). Government of China 1644- Cb: Govt of China. Routledge. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-1-136-90274-1.Pao C. Hsieh (May 1967). The Government of China, 1644-1911. Psychology Press. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-0-7146-1026-9.

- Eric Tagliacozzo; Helen F. Siu; Peter C. Perdue (5 January 2015). Asia Inside Out: Changing Times. Harvard University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-674-59850-8.

- Jonathan Manthorpe (15 December 2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan. St. Martin's Press. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-0-230-61424-6.

- R. G. Grant (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. DK Pub. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- Robert H. Felsing (1979). The Heritage of Han: The Gelaohui and the 1911 Revolution in Sichuan. University of Iowa. p. 18.

- Louise Lux (1998). The Unsullied Dynasty & the Kʻang-hsi Emperor. Mark One Printing. p. 270.

- Mark Mancall (1971). Russia and China: their diplomatic relations to 1728. Harvard University Press. p. 338. ISBN 9780674781153.

- Lo-shu Fu (1966). A Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western Relations, 1644–1820: Translated texts. Published for the Association for Asian Studies by the University of Arizona Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780816501519.