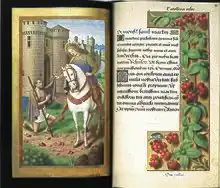

Recto and verso

Recto is the "right" or "front" side and verso is the "left" or "back" side when text is written or printed on a leaf of paper (folium) in a bound item such as a codex, book, broadsheet, or pamphlet.

In double-sided printing, each leaf has two pages – front and back. In modern books, the physical sheets of paper are stacked and folded in half, producing two leaves and four pages for each sheet. For example, the outer sheet in a 16-page book will have one leaf with pages 1 (recto) and 2 (verso), and another leaf with pages 15 (recto) and 16 (verso). Pages 1 and 16, for example, are printed on the same side of the physical sheet of paper, combining recto and verso sides of different leaves. The number of pages in a book using this binding technique must thus be a multiple of four, and the number of leaves must be a multiple of two, but unused pages are typically left unnumbered and uncounted. A sheet folded in this manner is known as a folio, a word also used for a book or pamphlet made with this technique.

Loose leaf paper consists of unbound leaves. Sometimes single-sided or blank leaves are used for numbering or counting and abbreviated "l." instead of "p." for the number of pages.

Etymology

The terms are shortened from Latin: rēctō foliō and versō foliō (which translate as "on the right side of the leaf" and "on the back side of the leaf"). The two opposite pages themselves are called folium rēctum and folium versum in Latin,[1] and the ablative rēctō, versō already imply that the text on the page (and not the physical page itself) are referred to.

Usage

In codicology, each physical sheet (folium, abbreviated fol. or f.) of a manuscript is numbered, and the sides are referred to as folium rēctum and folium versum, abbreviated as r and v respectively. Editions of manuscripts will thus mark the position of text in the original manuscript in the form fol. 1r, sometimes with the r and v in superscript, as in 1r, or with a superscript o indicating the ablative rēctō foliō, versō, as in 1ro.[2] This terminology has been standard since the beginnings of modern codicology in the 17th century.

In 2011, Martyn Lyons argued that the term rēctum "right, correct, proper" for the front side of the leaf derives from the use of papyrus in late antiquity, as a different grain ran across each side, and only one side was suitable to be written on, so that usually papyrus would carry writing only on the "correct", smooth side (and just in exceptional cases would there be writing on the reverse side of the leaf).[3]

The terms "recto" and "verso" are also used in the codicology of manuscripts written in right-to-left scripts, like Syriac, Arabic and Hebrew. However, as these scripts are written in the other direction to the scripts witnessed in European codices, the recto page is to the left while the verso is to the right. The reading order of each folio remains first verso, then recto, regardless of writing direction.

The terms are carried over into printing; recto-verso[4] is the norm for printed books but was an important advantage of the printing press over the much older Asian woodblock printing method, which printed by rubbing from behind the page being printed, and so could only print on one side of a piece of paper. The distinction between recto and verso can be convenient in the annotation of scholarly books, particularly in bilingual edition translations.

The "recto" and "verso" terms can also be employed for the front and back of a one-sheet artwork, particularly in drawing. A recto-verso drawing is a sheet with drawings on both sides, for example in a sketchbook—although usually in these cases there is no obvious primary side. Some works are planned to exploit being on two sides of the same piece of paper, but usually the works are not intended to be considered together. Paper was relatively expensive in the past; good drawing paper still is much more expensive than normal paper.

By book publishing convention, the first page of a book, and sometimes of each section and chapter of a book, is a recto page,[5] and hence all recto pages will have odd numbers and all verso pages will have even numbers.[6][7]

In many early printed books or incunables and still in some 16th-century books (e.g. João de Barros's Décadas da Ásia), it is the folia ("leaves") rather than the pages, that are numbered. Thus, each folium carries a consecutive number on its recto side, while on the verso side there is no number.[8] This was also very common in e.g. internal company reports in the 20th century, before double-sided printers became commonplace in offices.

See also

References

- e.g. Quibus carminibus finitur totum primum folium versum (rectum vacat) voluminis "These poems finish the full back page (the front is blank) of the first leaf of the volume" [Giovanni Battista Audiffredi], Catalogus historico-criticus Romanarum editionum saeculi XV (1783), p. 225.

- e.g. Roberts, Longinus on the Sublime: The Greek Text Edited After the Paris Manuscript (2011), 170; Wijngaards, The Ordained Women Deacons of the Church's First Millennium (2012), 232; etc. Tylus, Manuscrits français de la collection berlinoise disponibles à la Bibliothèque Jagellonne de Cracovie (XVIe-XIXe siècles) (2010)

- Martyn Lyons (2011). Books: A Living History. Getty Publications. p. 21. ISBN 9781606060834.

- Recto verso is an expression in French that means "two sides of a sheet or page". In Flanders the term recto verso is also used to indicate two-sided printing. Duplex printers are referred to as recto verso printers.

- Drake, Paul (2007). "The Basic Elements and Order of a Book". You Ought to Write All That Down. Heritage Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7884-0989-9.

- Gilad, Suzanne (2007). Copyediting & Proofreading For Dummies. For Dummies. p. 209. ISBN 9780470121719.

- Merriam–Webster, Inc. (1998). Merriam-Webster's Manual for Writers and Editors. Merriam–Webster. pp. 337. ISBN 9780877796220.

- See e.g. a modern reprint of the 3rd Década (1563): Ásia de João de Barros: Dos feitos que os Portugueses fizeram no descobrimento e conquista dos mares e terras do Oriente. Tercera Década. Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda, 1992.