Red Jacket

Red Jacket (known as Otetiani in his youth and Sagoyewatha [Keeper Awake] Sa-go-ye-wa-tha as an adult because of his oratorical skills) (c. 1750 – January 20, 1830) was a Seneca orator and chief of the Wolf clan, based in Western New York.[1] On behalf of his nation, he negotiated with the new United States after the American Revolutionary War, when the Seneca as British allies were forced to cede much land following the defeat of the British; he signed the Treaty of Canandaigua (1794). He helped secure some Seneca territory in New York state, although most of his people had migrated to Canada for resettlement after the Paris Treaty.

Red Jacket | |

|---|---|

| Otetiani, later Sagoyewatha | |

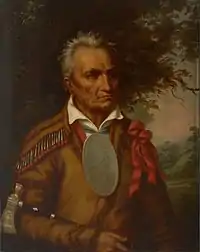

Red Jacket from an 1835 lithograph by Henry Corbould, after a painting by Charles Bird King, printed by Charles Joseph Hullmandel, and published in History of the Indian Tribes of North America | |

| Tribal chief of the Wolf clan | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1750 |

| Died | January 20, 1830 |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Seneca nation |

Red Jacket's speech on "Religion for the White Man and the Red" (1805) has been preserved as an example of his great oratorical style.

Life

Red Jacket's birthplace has long been a matter of debate. Some historians claim he was born about 1750 at Kanadaseaga, also known as the Old Seneca Castle. Present-day Geneva, New York, developed near here, at the foot of Seneca Lake.[2] Others believe he was born near Cayuga Lake and present-day Canoga.[3] Others say he was born south of present-day Branchport, at Keuka Lake near the mouth of Basswood Creek.[4][5] It is known that he grew up with his family at Basswood Creek, and his mother was buried there after her death. The Iroquois had a matrilineal kinship system, with inheritance and descent figured through the maternal line. Red Jacket was considered to be born into his mother's Wolf Clan, and his social status was based on her family and clan.

Red Jacket lived much of his adult life in Seneca territory in the Genesee River Valley in western New York. In the later years of his life, Red Jacket moved to Canada for a short period of time. He and the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant became bitter enemies and rivals before the American Revolutionary War, although they often met together at the Iroquois Confederacy's Longhouse. During the war, when most of both the Seneca and Mohawk were allies of the British, Brant contemptuously referred to Red Jacket as "cow killer". He alleged that at the Battle of Newtown in 1779, Red Jacket killed a cow and used the blood as evidence to claim he had killed an American rebel.[6]

Red Jacket became famous as an orator, speaking for the rights of his people. After the war, he played a prominent role in negotiations with the new United States federal government. In 1792 he led a delegation of 50 Native American leaders to Philadelphia. The US president George Washington presented him with a special "peace medal", a large oval of silverplate engraved with an image of Washington on the right-hand side shaking Red Jacket's hand; below was inscribed "George Washington", "Red Jacket", and "1792".

Red Jacket wore this medal on his chest in every portrait painted of him. The medal was held from 1895 to 2021 in the collection of the Buffalo History Museum.[7] In May 2021, it was repatriated to the Seneca Nation and is currently held in the collection of the Onöhsagwë:De' Cultural Center, also known as the Seneca-Iroquois National Museum.[8]

He was also presented with a silver inlaid half-stock long rifle, bearing his initials and Wolf clan emblem in the stock and his later name Sagoyewatha inlaid on the barrel. This rifle has been in private hands since his death.

In 1794, Red Jacket was a signatory, along with Cornplanter, Handsome Lake, and fifty other Iroquois leaders, of the Treaty of Canandaigua, by which they were forced to cede much of their land to the United States due to the defeat of their British ally during the war. Britain had ceded all its claims to land in the colonies without consulting the Iroquois or other Native American allies.[9] The treaty confirmed peace with the United States, as well as the boundaries of the postwar the Phelps and Gorham Purchase (1788) of most of the Seneca land east of the Genesee River in western New York.

In 1790 the Public Universal Friend and the Philadelphia Society of Friends were the first settlers in the formerly Seneca region. Despite the pillaging of the Native River-Settlement in Ah-Wa-Ga Owego, New York, by generals Clinton and Sullivan during the Revolutionary War, the Society made peace with the wary Seneca tribe. The Seneca Tribe made peace with settlers in the Finger Lakes region, but they suffered hardship in the Genesee Region and other parts of Western New York.[10]

In 1797, by the Treaty of Big Tree, Robert Morris paid $100,000 to the Seneca for rights to some of their lands west of the Genesee River. (This area developed as present-day Geneseo in Livingston County). Red Jacket had tried to prevent the sale but, unable to persuade the other chiefs, he gave up his opposition. As often occurred, Morris used gifts of liquor to the Seneca men and trinkets to the women to "grease" the sale.[11] Morris had previously purchased the land from Massachusetts, subject to the Indian title, then sold it to the Holland Land Company for speculative development. He retained only the Morris Reserve, an estate near the present-day city of Rochester. During the negotiations, Brant was reported to have told an insulting story about Red Jacket. Cornplanter intervened and prevented the Seneca leader from attacking and killing Brant.[12]

War of 1812

Red Jacket took his name, one of several he used as an adult, from a highly favored embroidered coat given to him by the British for his wartime services.[13] The Seneca allied with the British Crown during the American Revolution, both because of their long trading relationships and in the hope that the British could limit American encroachment on their territory. After the British were defeated, the Seneca were forced to cede much of their territory to the United States. Many of their people resettled in Canada at what is now the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario. In the War of 1812, Red Jacket supported the American side.[14]

Ambush at South of Chippawa

Peter B. Porter was able to successfully negotiate an alliance with Red Jacket to assist the American armed forces in the Battle of Chippawa. Red Jacket conceived of a plan to maneuver his force of 300 Seneca warriors close enough to ambush the enemy force which consisted of British regulars, Canadian militia, and Mohawkss. Peter B. Porter accompanied Red Jacket's force with a force of his own numbering 250-300 men. Porter's 250-300 man force consisted mostly of American militia and some U.S. regulars. Porter and Red Jacket headed with their combined force of 600 Senecas, militia, and regulars to ambush the British-allied force. Porter's 600 man force moved stealthily into the woods, creeping off to the south. The Americans entered the natural cover of the massive forest to stay out of sight of the enemy. The Americans came close undetected to the enemy's position. The Americans formed a formation of 3 arcs. Red Jacket's Senecas were in the 2 front arcs while Porter's men were in the third arc in the rear. Red Jacket's Senecas all wore white-hankie hats so that Porter's men could tell the difference between a British mohawk indian and a pro-American Seneca indian in the heat of battle. Once the Americans were in position enveloping the unsuspecting enemy. Each American aimed and leveled his gun at an enemy. The Americans sprang their ambush and opened heavy fire. The British-allied force was taken completely by surprise and many of them dropped dead. The Americans then charged in and engaged the enemy in close hand-to-hand combat. The Americans brutally killed many British, Canadian, and Mohawk as they were still so shocked and confused from the American ambush. The British and their allies retreated into the wilderness. Peter and his force pursued the enemy. However, the Americans ran into a fresh reserve of British regulars waiting in linear formation who fired a volley. Porter and his force retreated to safety as the British pursued them a short distance. After the battle of Chippawa ended between the main British army and the main American army, all British forces including the British main army withdrew temporarily. Porter and his men came back to their ambush site to police the scene to assess casualties of their force and of the enemy. There were at least 90 dead bodies of British, Canadian, and mohawks. There were only a dozen dead Americans on the field. The Senecas scalped all of the dead British, Canadian, and Mohawks. After that, Porter, Red Jacket, and their forces withdrew from the field.[15]

Later life

His later adult name, Sagoyewatha, which roughly translates as "he keeps them awake", was given by the Seneca about 1780 in recognition of his oratory skill. When in 1805 Mr. Cram, a New England missionary, asked to do mission work among the Seneca, Red Jacket responded by saying that the Seneca had suffered much at the hands of Europeans. His speech, "Religion for the White Man and the Red", expressed his profound belief that Native American religion was fitting and sufficient for Seneca and Native American culture. It has been documented and preserved as one of the best examples of North American oratory.[16]

Red Jacket developed a problem with alcohol and deeply regretted having taken his first drink (see following quote). When asked if he had children, the chief, who had lost most of his offspring to illness, said:

Red Jacket was once a great man, and in favor with the Great Spirit. He was a lofty pine among the smaller trees of the forest. But, after years of glory, he degraded himself by drinking the firewater of the white man. The Great Spirit has looked upon him in anger, and his lightning has stripped the pine of its branches.[17]

In his later years, Sagoyewatha lived in Buffalo, New York. On his death, his remains were buried in an Indian cemetery (now within Seneca Indian Park in South Buffalo, New York). In 1876, the politician William C. Bryant presented a plan to the Council of the Seneca Nation to reinter Red Jacket's remains in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo.[18] This was carried out on October 9, 1884. The proceedings, with papers documenting speeches given by Horatio Hale, General Ely S. Parker (Red Jacket's nephew's grandson, known as a "clan grandson," who inherited the famous medal[19]), and others, were published (Buffalo, 1884).[14] A memorial to Red Jacket, sculpted by James G. C. Hamilton, still stands within Seneca Indian Park.

According to Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography, "Several portraits were made of him. George Catlin painted him twice, Henry Inman once, and Robert W. Weir did his portrait in 1828, when Red Jacket was on a visit to New York City. Fitz-Greene Halleck has celebrated him in song."[14]

Speech to Rev. Cram

This famous speech, also known as his talk on "Religion for the White Man and the Red", is an example of his great skill as an orator. He spoke in 1805 as a response to a request by Jacob Cram, a New England missionary, to evangelize among the Seneca. On this day, the two men met in Buffalo Creek, New York, to discuss their religious beliefs.[20][21] After meeting with the leaders of the Seneca delegation, Red Jacket provided a thought-out response representing his people as a whole. He responded to Cram's words: "There is but one religion, and but one way to serve God, and if you do not embrace the right way, you cannot be happy hereafter". He argued peacefully that the European Americans and Native American peoples should each have the right to worship the religion that suits them best.

At the time, the Iroquois of present-day New York State were having difficulty dealing with the constant increase of European immigrants and encroachment on their remaining lands. As the numbers of European Americans grew in the Iroquois territories, the two peoples' opposing cultures became more and more apparent.

Red Jacket made it clear that he and his people would not change their religious beliefs based on the white man's word. He began, "It was the will of the Great Spirit that we should meet together this day. He orders all things, and has given us a fine day for our Council." He proceeded to count all the blessings on the day, attributing them to the Great Spirit. "For all these favors we thank the Great Spirit, and Him only."

Red Jacket said that his peoples' beliefs were very like those of the missionary, differing only in the names of their omnipresent and almighty creator. Their creation stories were the same. "There was a time when our forefathers owned this great island. Their seats extended from the rising to the setting sun. The Great Spirit had made it for the use of Indians. He had created the buffalo, the deer, and other animals for food . ... He had caused the earth to produce corn for bread. All this He had done for his red children, because He loved them." The difference between the faiths involved not whether an almighty creator existed, but which faith was the truth and deserved to be followed.

Red Jacket questioned the legitimacy of the white man's beliefs. "You say that you are sent to instruct us how to worship the Great Spirit agreeably to his mind, and, if we do not take hold of the religion which you white people teach, we shall be unhappy hereafter. You say that you are right and we are lost." Iroquois "separatist" belief held that there is not necessarily one true religion for all people. Red Jacket acknowledged that the European Americans' religious beliefs were based on a sacred text, but said, "If it was intended for us as well as you, why has not the Great Spirit given to us, and not only to us, but why did he not give to our forefathers, the knowledge of that book, with the means of understanding it rightly?"

In conclusion he urged his audience to accept different forms of belief. "The Great Spirit has made us all, but He has made a great difference between his white and red children ... to you He has given the arts. To these He has not opened our eyes. We know these things to be true. Since He has made so great a difference between us in other things, why may we not conclude that he has given us a different religion according to our understanding? The Great Spirit does right. He knows what is best for his children; we are satisfied." "We do not wish to destroy your religion, or take it from you. We only want to enjoy our own."

Civility

In his "Speech to the U.S. Senate", Red Jacket was respectful and open-minded regarding his visitors' beliefs, hoping that his audience would respond similarly. "We have listened with attention to what you have said. You requested us to speak our minds freely. This gives us great joy; for we now consider that we stand upright before you, and can speak what we think." He reassured his audience that he understood they were far from home, and would waste no time in giving them his answer.

On the relations between his people and the first white settlers to come to their land, he said, "They found friends and not enemies ... they asked for a small seat. We took pity on them, granted their request; and they sat amongst us. We gave them corn and meat; they gave us poison." He argued that it was wrong to portray his people as savages, when they had shown kindness but received in return only "poison" (hard liquor). Further,

Yet we did not fear them. We took them to be friends. They called us brothers. We believed them and gave them a larger seat ... they wanted more land; they wanted our country. Our eyes were opened, and our minds became uneasy. You have got our country, but are not satisfied; you want to force your religion upon us.

The white settlers' actions did not encourage belief in their religion. "How shall we know when to believe, being so often deceived by the white people?"

Red Jacket also acknowledged that the white settlers' religion was beset with divisive controversies, unlike his peoples' own faith.

We also have a religion, which was given to our forefathers, and has been handed down to us their children. We worship in that way. It teaches us to be thankful for all the favors we receive; to love each other, and to be united. We never quarrel about religion.

He wished his visitors well. "You have now heard our answer to your talk, and this is all we have to say at present. As we are going to part, we will come and take you by the hand, and hope the Great Spirit will protect you on your journey, and return you safe to your friends."

Rhetoric

Red Jacket's "Speech to the U.S. Senate" expresses his ability to use a distinct form of rhetoric that distinguishes the difference in religious tolerance between the Indians and United States citizens. His emotional appeal to members of the US Senate, whom he feels are neglecting the Indians' right of religious freedom, is an example of his attempt to persuade his audience to recognize their fallacies. He repeatedly refers to the Great Spirit, who he believes oversees both the red and white man.

At the beginning, he says,

But we will first look back a little, and tell you what our fathers have told us, and what we have heard from the white people". Red Jacket is referring to the history of how the white man has treated the red man on the latter's native soil. The white man commonly tried to persuade the Indians, whom he considered less fortunate, to adopt the ways of Western society. Red Jacket noted the European Americans had tried to force their religion on the Indian peoples. Red Jacket recognized religion as a cultural right, but he explained that the Indians had inherited their belief system within their culture just as the European Americans had been given the Bible and Christianity. He said that both people came from a similar Great Spirit, yet it is up to the beholder as to how he accepts religion. The attempts of European Americans to force Christianity on the Indians violated the liberties of both people. Red Jacket said, "You have now become a great people, and we have scarcely a place left to spread our blankets. You have got our country, but are not satisfied; you want to force your religion upon us.

Red Jacket continues to identify the religious continuities that exist between both people with his elaboration on the Great Spirit. He states, "You say there is but one way to worship and serve the Great Spirit. If there is but one religion, why do you white people differ so much about it? Why not all agreed, as you can all read the book?". Red Jacket distinguishes the fallacies that exist between the Americans' speech and their actions. If the Indians are being secularized for their religious beliefs, yet they believe in one ultimate Creator, just like the European Americans, how can they be viewed as a lesser body? Red Jacket says they do not understand the European Americans' mission to eradicate the Indians based on religion, but Red Jacket sees the European Americans as divided in their beliefs. However, he goes on to say that the Great Spirit is not one that can tear the two people apart but ultimately unite them in their ability to peacefully coexist.

Red Jacket's ability to distinguish this form of religious discussion was very favorable to his legacy in history. He argues the injustices of the cultural system in the time period but does not back away from recognizing their common cultural and religious beliefs.

Honors and legacy

A variety of structures, ships and places were named in his honor, especially in the Finger Lakes region and Buffalo:

- A complex of dormitory buildings at the University at Buffalo

- Red Jacket Dining Hall at SUNY Geneseo.

- The Red Jacket Building, an apartment and commercial building in Buffalo.

- A memorial statue and Red Jacket Park are in Penn Yan, New York near Keuka Lake. The statue was sculpted by Michael Soles.

- Red Jacket Yacht Club, which lies on the western shores of Cayuga Lake.

- The Red Jacket clipper ship, which set the unbroken speed record from New York to Liverpool.[1]

- A public school system, Red Jacket Central, which serves the communities of Manchester and Shortsville in Ontario County, New York.[22]

- The Red Jacket Volunteer Fire Department, which served the Town of Seneca Falls.

- A section of land on the Buffalo River (New York) is named "Red Jacket Peninsula". On the eastern bank of the river is the plaque containing a brief bio of Red Jacket and river history.

- Red Jacket Parkway in South Buffalo

- The community of Red Jacket in southern West Virginia, although the leader was not known to have had any connection to that region.[23]

- There is a hand-carved portrait of Red Jacket alongside a brief quotation from his Senate speech on the Empire State Carousel at the Farmers' Museum in Cooperstown, NY.

Red Jacket wearing the "Peace Medal" given to him by George Washington. Portrait by Charles Bird King, ca. 1828, Colby College Museum of Art.

Red Jacket wearing the "Peace Medal" given to him by George Washington. Portrait by Charles Bird King, ca. 1828, Colby College Museum of Art. The Trial of Red Jacket, by John Mix Stanley, 1869.

The Trial of Red Jacket, by John Mix Stanley, 1869._-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Portrait by Thomas Hicks (1868), National Portrait Gallery

Portrait by Thomas Hicks (1868), National Portrait Gallery Chief Red Jacket, with Two Warriors, by George Catlin

Chief Red Jacket, with Two Warriors, by George Catlin

See also

- U.S. Constitution, Native American influence

Further reading

- Graymont, Barbara, The Iroquois in the American Revolution, 1972, ISBN 0-8156-0083-6

- Robert G. Koch, "Red Jacket: Seneca Orator", Crooked Lake Review, March 1992

Footnotes

- Maine League of Historical Societies and Museums (1970). Doris A. Isaacson (ed.). Maine: A Guide 'Down East'. Rockland, ME: Courier-Gazette, Inc. pp. 260–261.

- John Niles Hubbard, "An Account of Sa-Go-Ye-Wat-Ha"

- Col. William L. Stone (1838), Life of Red Jacket

- Miles A. Davis (1912), History of Jerusalem, p. 38

- Stafford C. Cleveland (1873), History of Yates County, p. 450

- Graymont, pg. 216

- "Fact, Fiction & Spectacle: the Trial of Red Jacket". Buffalo History Museum. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- McCarthy, Robert J. (16 May 2021). "Red Jacket Medal's long journey ends at Seneca museum". Buffalo News. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- "The Canandaigua Treaty of the 1794". Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- Wisbey, Herbert A., Jr. (2009). Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson the Publick Universal Friend. Cornell Press.

- Goldman, Mark (1983). High hopes : the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780873957342.

- The Cornplanter Chronicles, Vol. 4, part 7, Mountain Laurel Review

- William Jennings Bryant, ed. (1906). "The World's Famous Orations. America: Vol I. (1761–1837)". Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- "Dispatches from the War of 1812 "Guerrillas in a Thrilla: The Battle of Chippawa, Part 2"". History Of Buffalo. 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Red Jacket on Religion for the White Man and the Red", Bartleby Website, accessed 22 May 2011

- Lossing, Benson J. (1876). A Centennial Edition of the History of the United States. Hartford: T. Belknap. p. 26. ISBN 9781177937429.

- "The Graves of Red Jacket". wnyheritagepress.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Armstrong, William H. (1978). Warrior in Two Camps: Ely S. Parker. Syracuse Univ. Press. p. 204. ISBN 0-8156-2495-6.

- "Red Jacket Defends Native American Religion, 1805". historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

- "Great Native American Speeches". www.eacfaculty.org. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

- "Home". redjacket.org.

- Kenny, Hamill (1945). West Virginia Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning, Including the Nomenclature of the Streams and Mountains. Piedmont, West Virginia: The Place Name Press. p. 524.

References

- Baym, Nina, Robert S. Levine, and Arnold Krupat. The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Vol. A. New York: W. W. Norton &, 2007. Print.

- Stone, William L. Life and times of Red-Jacket, Or, Sa-go-ye-wat-ha: Being the Sequel to the History of the Six Nations. New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1841. Print.

External links

- An Account of Sa-Go-Ye-Wat-Ha, or Red Jacket, and His People at Project Gutenberg by John Niles Hubbard

- Red Jacket on Religion for the White Man and Red, Audio from Greatest Speeches in History Podcast

- "Red Jacket on Religion for the White Man and the Red", Bartleby Website, text online

- "Red Jacket, noted Indian orator, colorful character", Wisconsin History