Reddish

Reddish is an area in Metropolitan Borough of Stockport, Greater Manchester, England. 4.6 miles (7.4 km) south-east of Manchester city centre. At the 2011 Census, the population was 28,052.[1][2] Historically part of Lancashire, Reddish grew rapidly in the Industrial Revolution and still retains landmarks from that period, such as Houldsworth Mill, a former textile mill.

| Reddish | |

|---|---|

Houldsworth Square in central Reddish | |

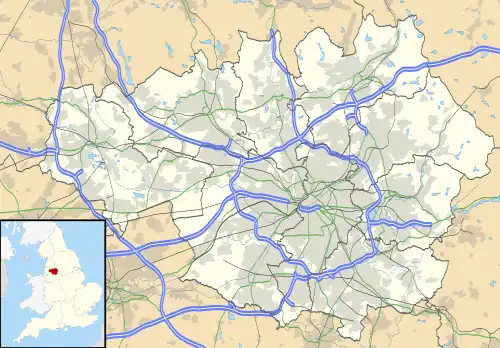

Reddish Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Area | 2.73 sq mi (7.1 km2) |

| Population | 28,052 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 11,009/sq mi (4,251/km2) |

| OS grid reference | SJ893935 |

| • London | 159 mi (256 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | STOCKPORT |

| Postcode district | SK4, SK5 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Reddish Vale is a country park.

History

Toponymy

Reddish is recorded as Redich (1205, 1212), Redych, Radich (1226), Radish, Rediche (1262), Redditch (1381), Redwyche, Radishe and Reddishe (16th century).[3][4] The name either means "reedy ditch" (OE hrēod-dīc) or "red ditch" (OE rēad-dīc). Ekwall (1922) allows either form, stating "red" is less probable; Mills (1991) and Arrowsmith (1997) only give the "reed" option.[5][6][7] The ditch referred to is possibly the Nico Ditch,[6] an earthwork of uncertain origin bordering Reddish, Manchester and Denton.[8] Folklore has it that the names Gorton and Reddish arose from a battle between Saxons and Danes.[4][9][10] John Higson wrote in 1852[10]

The neigh'ring trench is called the Nicker Ditch

Flowing with blood, it did the name convey

To th' bordering hamlet, Red-Ditch. Near here, Where

the last 'tween the foes was fought,

Where victory was won, that memorable

Eminence proudly was distinguished

By the name of Winning Hill. The streamlet

Aforemention'd gains appellation

Of Gore Brook, also the contiguous

Happy hamlet through which it floweth still

Bears, in glorious commemoration,

And e'er shall, the honour'd name of Gore Town.

Farrer and Brownbill dismiss this interpretation as "popular fancy".[11]

1066 to late 18th century

Reddish does not appear in the Domesday survey; this is in common with most of the then southeast Lancashire area.[12] A corn mill is known to have existed at the junction of Denton Brook and the River Tame from about 1400 onwards.[13] The two main mediaeval houses were Reddish Hall at grid reference SJ899932 (demolished 1780,[3] but visible on maps dated 1840) and Hulme Hall at grid reference SJ889926, later known as Broadstone, then Broadstone Hall (demolished 1945[14]). The Reddish family were major landowners in the area from at least 1212 to 1613 when title passed by marriage to the Coke family. It passed down the family to Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester, who sold his land in Reddish at the end of the 18th century, and in 1808 it was bought by Robert Hyde Greg and John Greg.[3] There were Hulmes in Reddish in the 13th century, and the land passed through the family until about 1700 when it was given to a charitable trust.[3]

Very few buildings in Reddish pre-date the 19th century. Canal Bridge Farm, close to Broadstone Mill, is dated to the mid to late 18th century (the name is later).[15] Hartwell dates a small group of farm buildings and cottages at Shores Fold, near the junction of Nelstrop Road and Marbury Road, to the sixteenth and late seventeenth to early 18th century. These would have been on the traditional Reddish – Heaton Norris border, but are now firmly inside Heaton Chapel.[16]

Industrial Revolution

The Stockport Branch Canal passed through Reddish and opened in 1797.[17] It seems to have had little effect by 1825, when Corry's description of Reddish, in full, was "The population of Reddish is but thin".[18] Booker states that in 1857 Reddish was almost entirely agricultural, being made of meadow and pasture (1,320 acres (5.3 km2)); arable land (90 acres (360,000 m2)); wood and water (50 acres (200,000 m2)); and buildings and streets (44 acres (180,000 m2)). At that time, Reddish contained "neither post-office, schoolmaster, lawyer, doctor, nor pawnshop".[19] The population increased over tenfold in the next fifty years with the Industrial Revolution.

The water-powered calico printworks in Reddish Vale on the River Tame is known to have been working before 1800. Industrial development followed the line of the canal[20] and was steam-powered throughout. A variety of manufacturers moved into Reddish during this period.

Robert Hyde Greg and John Greg, sons of Samuel Greg of Quarry Bank Mill, who owned about a third of Reddish by 1857,[21] opened Albert Mills for cotton spinning in 1845. Moor Mill, manufacturing knitting machines, was built around the same time. William Houldsworth's Reddish Mill for cotton spinning was opened in 1864. Hanover Mill was built in 1865 for cotton spinning, but in 1889 was converted to make silk, velvet, woven fur etc.

The Reddish Spinning Company, partly owned by Houldsworth, opened in 1870. Furnival & Co, making printing presses, opened in 1877.[22] Andrew's Gas Engine works opened in 1878.[23] The Manchester Guardian's printworks opened in 1899. Craven Brothers, a manufacturer of machine tools and cranes, opened the Vauxhall Works on Greg Street, in 1900.[24] Broadstone Spinning Company opened a large double mill in 1906/7. These major employers were accompanied by numerous smaller concerns, including dyeworks, bleachworks, wire ropeworks, brickworks, screw manufacturers, makers of surveying equipment, and a tobacco factory.[25]

A small number of closures of major industrial employers took place in the first half of the 20th century, due to the ebb and flow of trade. Andrew's Gas Engine Works was taken over in 1905 by Richard Hornsby & Sons of Grantham,[26][27] the business was transferred to Grantham and the Reddish works closed some time during the great depression following WWI.[27] Cronin indicates that the works were still in operation in 1930.[28] The Atlas wire rope works closed in 1927.[29]

Reddish took its share of the decline in Lancashire cotton production and finishing. Broadstone Mills ceased production in 1959;[30] Reddish Mills closed in 1958 with the loss of 350-400 jobs;[31][32] Spur Mill followed in 1972;[33] and the long-lived Reddish Vale printworks closed by 1975;[34] Albert Mill continued to trade as R. Greg and co under new ownership, but finally closed in 1982.[28] Ashmore wrote in 1975 that "Stockport has ceased to be a cotton town."[35]

The decline of Broadstone Mills was accompanied by high farce. In November 1958 the company sold a number of spinning mules as scrap for just over £3,000. By agreement, the machines remained in the mill over the winter. A small number had been broken and removed by April 1959, when the government announced a compensation package for firms that agreed to scrap spinning capacity. As the title in the mules had passed to the scrapman, it was decided that the company was not entitled to compensation amounting to over £60,000, despite the fact that the machinery was still on its premises. Actions in the High Court and the Court of Appeal in 1965 were fruitless.[36][37]

Some of the mills vacated by the spinners found other uses. The Reddish Spinning Company's mill was taken over by V. & E. Friedland who became the world's largest manufacture of doorbells; an extension to the mill won several architectural awards.[38] The mill is now residential. Broadstone Mill was partly demolished, but now houses small commercial units.[39] Regeneration efforts at Houldsworth Mill were instrumental in Stockport Council winning British Urban Regeneration Association's award for best practice in regeneration.[40] £12 million has been spent to convert the mill into mixed use.[41] The area around Houldsworth mill is now designated as a conservation area.[42][43]

Brewing, pubs and clubs

Reddish has been home to at least three breweries. Richard Clarke & Co brewed in the area for over 100 years, before being taken over, and later closed, by Boddingtons in 1962.[44][45] David Pollard's eponymous brewery opened in the former print works in Reddish Vale in 1975, moving out to Bredbury in 1978; the business went into liquidation in 1982.[46] The small 3 Rivers Brewery started brewing in Reddish in 2003 but had ceased brewing when the company was wound up in 2009.[47][48]

The pub stock is not well-regarded: "Never offering the best selection of pubs in the borough, it is now easily the worst area for real ale availability ..."[49] is a typical description. It has been suggested that this may be a consequence of Robert Hyde Greg's disapproval of alcohol,[50] (due to the alcoholism of an uncle of his father, see also Samuel Greg). The pubs are supplemented by several working men's and political clubs. The Houldsworth WMC was awarded a blue plaque by Stockport MBC in December 2006.[51] Reddish WMC was founded by in 1845 by millowner Robert Hyde Greg as a Mechanics' Institute and Library. Its members claim it to be the oldest club registered with the CIU.[52][53]

Governance

The extents have been well-defined for at least several hundred years. Reddish was a township in the ancient parish of Manchester, but lay outside the Manor of Manchester. This had the effect that boundaries of Reddish were described by the boundaries of the Manor of Manchester, with the exception of that with Cheshire, which was the River Tame. The manor boundaries were surveyed and recorded in 1322, and the relevant part was:[54]

following the said water [Tame] to the mid [stream] between the county of Chester and Assheton unto the Mereclowe at Redyshe so following Mereclowe unto Saltergate, from thence following the ditch of Redyshe unto Mikeldiche, following that unto Peyfyngate, following that unto Le Turrepittes between Heton Norreyes and Redishe, from thence following Le Merebroke unto the confluence of the waters of Tame and Mersey

"Mere" means boundary in this context. The description was traced into early 20th century features by Crofton[55][56] and can be cast as

following the middle of the Tame as far as Denton Brook at Reddish; and so following Denton Brook and a tributary as far as Thornley Lane South; and then following Thornley Lane as far as Nico Ditch; and following Nelstrop Road as far as the turf-pits between Heaton Norris and Reddish (these are lost); and from there following Black Brook as far as near the conjunction of the waters of the Tame and Goyt.

However, Black Brook cannot be le Merebroke as it does not flow to the Tame, but joins Cringle Brook, which flows into the Mersey several miles away via Chorlton Brook. With this exception, Crofton's interpretation of the 1322 boundaries matches those shown on Ordnance Survey maps of the 19th century.

Reddish became an urban district in 1894.[57] By 1901 the neighbouring County Borough of Stockport had effectively run out of land, and was overflowing into abutting districts. In 1901, after petitioning the Local Government Board, Stockport expanded into several areas including the whole of Reddish, described by Arrowsmith as Stockport's "greatest prize".[58][59] Stockport gained Reddish's tax income and building land, and in return Reddish received several civic amenities. A council school opened in 1907,[60] and a combined fire station, free library, and baths opened in stages during 1908 (Cronin identifies a small building at the rear as a mortuary).[61] The council opened new municipal parks at Mid Reddish (on land presented by Houldsworth) and at South Reddish.[62] A park at North Reddish followed, described in 1932 as "recently laid out, provid(ing) a number of horticultural features combined with recreation facilities, and illustrat(ing) the layout of a modern recreation park".[63] At that time, the Stockport Canal and the Reddish Iron Works made up two of the park's boundaries.

The separate civil parish was merged into Stockport parish in 1935.[64] Reddish's position north of the Tame means it was historically part of Lancashire.[57] On the merger with Stockport in 1901 the boundary between Lancashire and Cheshire was moved to place it in Cheshire.[65] In 1974 Stockport and several adjacient territories became a unified metropolitan borough in the newly created metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.

Parliamentary representation

The parliamentary constituency of Denton and Reddish has been represented by Labour MP Andrew Gwynne since 2005. At the 2010 general election, Gwynne got 51% of votes, and the second-placed Conservative candidate 25%.[66] The seat has been held by Labour since its creation in 1983.

Council representation

Reddish is divided into two wards (Reddish North and Reddish South) for the purpose of electing councillors to Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Each ward returns three councillors.

As of May 2020, Roy Driver, David Wilson and Kate Butler (all Labour) represent Reddish North; Janet Mobbs, Jude Wells (both Labour) and Gary Lawson (The Green Party) represent Reddish South. The 2021 local election saw Reddish South's first independent candidate, Daniel Zieba, who came fourth, beating the Liberal Democrats.[67]

Geography

Reddish borders Heaton Chapel and Brinnington of Stockport; Denton of Tameside; and Gorton and Levenshulme of the City of Manchester.

Reddish is a densely populated area and is near to affluent parts of Greater Manchester, such as Heaton Chapel and Heaton Moor. Reddish continues to be an attraction to many people in the Greater Manchester area to work, live and relax.

Climate

Reddish has a mild climate. The main population is situated along a linear stretch parallel with Reddish Vale. Reddish Vale and the lower lying land in the valley is often cooler and effectively a 'frost pocket'. It is still mild comparatively speaking; temperatures on a clear night will likely be colder than the land at the top of valley floor or, roughly speaking, along Reddish Road/Gorton Road. The effects of a Fohn Wind are often present here, where the warm air rises from the valley floor, tempering the air at the top and thereby reducing overnight lows, more particularly in winter.

As a comparison, temperatures on any given clear night throughout the year can be between 1-3 degrees C warmer than the Manchester weather station, situated at the nearby Woodford Aerodrome, but on a cloudy night are almost equal. Daytime highs are similar and predominately almost exacting to Woodford, though fluctuations due to localised weather patterns can produce variations.

Again, on a cloudy day, the temperatures can be slightly cooler than Woodford. Dependent on the prevailing weather patterns and the wind direction, temperatures can be either lower by around 1 degree C and occasionally (more noticeably on a warm sunny day) and in the absence of early morning mist/fogs(common in Woodford and Reddish Vale) can be up to 2 degrees C warmer than Woodford.

Due to its suburban nature and geographical location, close to the municipal centres of Stockport and Manchester, it benefits from an 'urban heat island' effect.

Most of Reddish would be equivalent to Usda Zone 8B/9A in recent years and, with the influence of global warming, with typical annual minimum lows of around -5/-6C.

Summer high temperatures average around 20-21C and peak at around 28C in any given year, occasionally to around 32C. Overnight lows average around 12-14C typically.

Winter high temperatures average around 6-9C. Winter overnight lows typically average around 3C.

Many tender plants can grow here and in the Stockport/Manchester area in general; the municipal planting consists of much New Zealand flora, such as Phormiums and Cordylines and Mediterranean plantings such as European Fan Palms and Canary Island date palms and Yuccas in residential gardens are commonplace.

Weather data specifically for South Reddish can be found here : https://web.archive.org/web/20110710210003/http://www.everyoneweb.com/palmsnexotics/

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1774 | 302 | — |

| 1811 | 456 | +1.12% |

| 1821 | 574 | +2.33% |

| 1831 | 860 | +4.13% |

| 1841 | 1,188 | +3.28% |

| 1851 | 1,218 | +0.25% |

| 1861 | 1,363 | +1.13% |

| 1901 | 8,668 | +4.73% |

| 1911 | 14,252 | +5.10% |

| [50][68][69] | ||

The most recent data is from the United Kingdom Census 2001. The census data below is based on the North Reddish and South Reddish wards. The modern South Reddish ward contains a small area that was traditionally part of Heaton Chapel and Heaton Norris; some of Reddish has been transferred to Heaton Chapel.

White British is the predominant ethnicity. For the North Reddish ward, just under 97% of the population of 16,120 were identified as white (including Irish and other white), 1.48% as mixed-race, 0.73% as black, 0.6% as Chinese and 0.43% as Asian. For the South Reddish ward, just under 96% of the population of 13,935 were identified as White, 1.28% as mixed race, 1.28% as Asian, 0.86% as Black and 0.84% as Chinese.

The housing stock remains mainly terraced and semi-detached. For the North Reddish ward, the 6,914 housing units were divided into 8% detached house, 46% semi-detached, 36% terraced and 10% flats. For the South Reddish ward, the 6,598 housing units were divided into 5% detached house, 29% semi-detached, 44% terraced and 22% flats. There are no tower blocks in Reddish,[70] unlike several neighbouring areas.

Some housing built by factory owners for their employees remains. Greg Street, Birkdale Road and Broadstone Hall Road South have mid-19th century terraces built by the Gregs for the workers at their, now demolished, Victoria and Albert Mills.[71] Furnival Street was built in 1886 to house workers at the (demolished) Furnival's ironworks[72] The largest collection is that built by Houldsworth near to his Reddish Mill, even though only Liverpool Street and Houldsworth Street remain after clearance in about 1974.[73] The houses on Houldsworth Street, directly facing the mill, are grander and would have been for the higher placed workers.[74]

Economy

The shopping area around Houldsworth Square contains about eighty small shops[75] and has been chosen as one of eight areas to benefit from the Agora Project,[76][77] an EU-funded project to reverse the decline in local shopping areas.

Stockport MBC describes Reddish as one of the eight major district centres in the borough that offer "local history, modern convenient facilities and traditional high street retailing". The other seven are Bramhall, Cheadle, Cheadle Hulme, Edgeley, Hazel Grove, Marple and Romiley.[78]

Reddish is home to many tertiary services. Houldsworth Square, named after local Victorian era mill-owner William Houldsworth), has many shops and banks serving the local population. There are schools, such as Reddish Vale Technology College in South Reddish, which in 2006 became the only school in Greater Manchester to be announced by the Government as a 'Trust Pathfinder' school. In 2014, the school was judged by OFSTED as "an inadequate school" and was later put into special measures.

Affluence

There are several measures of overall wealth and poverty. The Human Poverty Index calculates a value based on longevity, literacy, unemployment and income. High values indicate increasing poverty. The parliamentary constituency scores 14.4, close to the UK average of 14.8. This compares well with neighbours Manchester Gorton (20.5) and Stockport (14.2), but poorly with the other Stockport constituencies of Hazel Grove (10.9) and Cheadle, placed third best in the UK with a value of 7.9.[79]

On a narrower level, the estimated household weekly income for the period April 2001 to March 2002 for North and South Reddish wards was £440 and £400 respectively. In comparison with nearby wards, this is higher than Gorton North, Gorton South and Brinnington (at £350, £330 and £340 respectively), slightly lower than Denton West (£480) and significantly lower than Heaton Moor and Heaton Mersey (£590).[80] The averages for the North-West region and the UK were £489 and £554 respectively (2001–4).[81]

Landmarks

Reddish is home to several listed buildings and structures.[82] All the Grade I and Grade II* listings are part of Houldsworth's community.

*Grade I

- St. Elisabeth's Church and wall at St. Elisabeth's Church (Grade II*)

- Grade II*

- Houldsworth Mill, Houldsworth Street. Designed by Abraham Henthorn Stott. Opened 1860s, closed as a cotton mill 1958.

- Houldsworth Working Men's Club, Leamington Road. Designed by Abraham Henthorn Stott. Opened 16 May 1874.

- St Elisabeth's C of E Primary School (Houldsworth School), Liverpool Street. Wall at St. Elisabeth's C of E Primary School, Liverpool Street. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse. Consecrated 1883.

- St. Elisabeth's Church Rectory and wall at St. Elisabeth's Church Rectory, Liverpool Street. Designed by Alfred Waterhouse.

- Grade II

- Broadstone Mill House, Broadstone Road

- Clock and drinking fountain, Houldsworth Square

- North Reddish Infant & Junior School, Lewis Road

- Tame Viaduct, Reddish Vale

- 40 Sandy Lane

- Shoresfold Farmhouse and numbers 2 and 4 Marbury Road

- Locally listed

- Bull's Head Building, formerly the Bull's Head pub, Gorton Road. Now occupied by Manchester Vacs, a retailer and repairer of vacuum cleaners.[83]

Transport

Buses

The B6167 was designated a Quality Bus Corridor in 2004[84] and a number of modifications made. As of 2006, any improvements have not been quantified. The main bus route is the high frequency service 203 operated by Stagecoach Manchester, which runs from Stockport via Reddish and Gorton to Manchester city centre. Less-frequent services run to Ashton via Gorton & Droylsden; Ashton via Denton; Manchester via Didsbury and Rusholme; Hazel Grove; and Wythenshawe.[85]

Canal

The Ashton Canal and the Stockport Branch Canal were built to join Manchester and Stockport to the coal mines in Oldham and Ashton-under-Lyne. The branch was dependent on the main for its utility, and hence its planning, passing through parliament, and construction came after that of the main. The main opened in 1796 and the branch in 1796. The branch was just under five miles (8 km) long; it left the Ashton Canal at Clayton, passed through Gorton & Reddish and terminated just over the boundary in Heaton Norris, adjacent to what was then the main turnpike between Manchester and Stockport. The Beat Bank Branch Canal was planned as a sub-branch and was intended to cross Reddish Vale to a colliery at Denton, but the scheme was abandoned by 1798.[86][87] By 1827, the canal was bringing coal to Stockport from as far as Norbury and Poynton.[88]

The canal was purchased by the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway in 1848.[87] Traffic declined and the canal was described as derelict as early as 1922.[25] Commercial traffic ceased in the 1930s;[87] the canal was declared officially closed in 1962 and filled in.[89]

Roads

The B6167 is the main road through Reddish; it allows access to the A57 for Manchester or the M60/M67 junction at the north, and to Stockport and the M60 to the south. The road, currently designated Sandy Lane, Reddish Road, Gorton Road and Reddish Lane, was turnpiked by the Manchester, Denton and Stockport Trust following an Act of 1818.[87][90]

Railway

Reddish North railway station lies on the Hope Valley Line between Sheffield, New Mills Central and Manchester Piccadilly. Services are generally half-hourly on Mondays to Saturdays, hourly on Sundays.

Reddish South railway station only has a weekly return parliamentary service on Saturday mornings, running between Stockport and Stalybridge.

The history of the development of rail infrastructure in the UK is complicated, with lines and stations being built by a myriad of railway companies and joint ventures. Routes did not always follow the best path; they were created, altered or blocked through lobbying of parliament by interested parties intent on protecting their interests and preventing competition. Due to their strategic position between Manchester and London, Stockport and Reddish played their parts. Reddish played host to three railway lines, two railway stations and a traction depot. To improve readability, the names of the stations and lines are the latest (or last) used.

Reddish South

The West Coast Main Line running between Manchester Piccadilly and London via Crewe was opened in 1840-2 by the Manchester and Birmingham Railway (M&B), crossing the Mersey valley on a large viaduct at Stockport. In 1849, a line was opened from the north side of the viaduct via Reddish South and Denton stations to join the Woodhead Line (Piccadilly to Sheffield) of the Sheffield, Ashton-Under-Lyne and Manchester Railway (SA&MR) at Guide Bridge. A short branch went to Denton Colliery. The station at Reddish South contained a large goods yard and trade through the station played an important role, alongside the canal, in the industrialisation of the area.[91]

The M&B became part of the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) by 1849; the SA&MR became part of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&L) in 1847. At this stage, both companies used Piccadilly as their Manchester terminus. The LNWR held a monopoly on the important London route.[91]

Reddish North

In 1862, the MS&L built a line from Hyde Junction to near Compstall on the River Goyt. In 1865, this was extended over the river to New Mills and later joined the Midland Railway's Derbyshire lines. By 1867, Midland trains were running from London to Piccadilly via this (considerably longer) route, providing competition to the LNWR. In 1875, the Sheffield and Midland Railway Companies' Committee, a joint venture between the MS&L and the Midland, opened a new more direct route from near Romiley to Piccadilly giving Reddish its second station, Reddish North.[91]

Reddish Electric Depot

The Midland was given notice to leave Piccadilly in the same year that Reddish North opened and construction of Manchester Central railway station started.[91] The Fallowfield Loop line was opened in 1892, to allow access from the Woodhead Line to Manchester Central and Trafford Park, passing through a corner of Reddish. Stations were built just outside Reddish at Hyde Road and Levenshulme South.[92] In 1936, the MS&L's successor, the London and North Eastern Railway, planned to electrify the Woodhead Line and the Fallowfield Loop line, primarily for shipping coal from Yorkshire, but World War II interrupted progress.

After the war, the railways were nationalised as British Rail (BR). The electrification plan was put in place as the Manchester-Sheffield-Wath electric railway, opening in 1954 using a 1500 V DC system.

Reddish Electric Depot was constructed to maintain the Class 76 & Class 77 locomotives and Class 506 electric multiple units; the depot was also used to house the prestigious Midland Pullman in the early 1960s. The building was 400 ft (120 m) long. However, electrification was not continued beyond the depot to Trafford Park.[92][93] Shortly afterwards, BR adopted the 25 kV AC system for electrification, with the effect that the Woodhead Line "passed very quickly from ultra-modern to obsolescent".[94]

Local passenger services stopped using the Fallowfield Loop line in 1958, although through trains continued until 1969.[92][93] The Beeching Report of 1963 recommended that the Woodhead Line be retained and the Hope Valley line, serving Reddish North station, to be closed; in 1966, BR controversially implemented the reverse.[94]

The depot continued to service locomotives and electric multiple units until the Woodhead Line was closed in 1981. Despite rumours that the depot would be used to service the Manchester Metrolink, the depot fully closed in 1983; it was quickly vandalised and has since been demolished. The Fallowfield Loop line closed completely in 1988 and the track was taken up.[92][95] The site has since been redeveloped as a housing estate.

Education

Reddish's only secondary school is Reddish Vale High School. Sited on the edge of the green belt, the school has its own farm and is characterised by OFSTED as "an inadequate school" as of 2014. It teaches about 1,400 pupils from the ages of 11 to 16, but does not have a sixth form.[96][97][98][99]

As of 2007, Reddish has ten nursery and primary schools, including some church schools (Roman Catholic and Church of England).[100][101] It has been proposed to close three of these and build a new school. The site chosen was formerly a clay pit for a brickworks and later a landfill site. Much of the landfill took place before modern controls and there is local concern about the suitability of the site.[102][103][104]

Community facilities

Of the 1907 facilities provided by Stockport, only the library is still open. The baths closed in 2005; there is a campaign to reopen them,[105] but it does not have the backing of the council.[106] The ground floor of the fire station is used as a community centre. The mortuary closed in the 1980s.[14]

Religion

Reddish falls in the Diocese of Manchester for the Church of England, and the Diocese of Salford for the Roman Catholic Church.

- St Agnes, Gorton Road;[107][108] (Church of England). 1908, brick, some good glass.[109]

- Bethel Christian Centre/Reddish Community Church/Bethel Apostolic Church, Sykes Street; (Apostolic Church).

- Christ Church, Lillian Grove;[110] (Methodist/United Reformed Church).

- St Elisabeth, Lemington Road;[111][112] (Anglo-Catholic - Church of England); 1883 Victorian Gothic building by Alfred Waterhouse. Paid for by Houldsworth

- Holy Family, Thornley Lane North;[113] (Roman Catholic).

- St Joseph, Gorton Road[114] (Roman Catholic).

- St Mary, Reddish Road;[115] (Church of England). Reddish's first church, built 1862-4[69][116] at a cost of £2500 in the "decorated English style".[69] The parish was carved from Heaton Norris, and is still known as Heaton Reddish.

- Reddish Christian Fellowship, Broadstone Road;[117] sited in an end-of-terrace house.

- Stockport Seventh-day Adventist Church, Coronation Street;[118] (Seventh-day Adventist Church); modern building.

St Elisabeth's Church. The shadow across the roof is cast by the chimney from the nearby Reddish (Houldsworth) Mill.

St Elisabeth's Church. The shadow across the roof is cast by the chimney from the nearby Reddish (Houldsworth) Mill. St Joseph's Church

St Joseph's Church St Joseph's Church interior

St Joseph's Church interior

Notable people

- Norman Foster was born in Reddish in 1935 and went on to study architecture at the University of Manchester. Foster is one of the leading architects in the world and is noted for buildings including 30 St Mary Axe, the new Wembley Stadium, Hearst Tower, Torre Caja Madrid and Deutsche Bank Place. His work under-construction includes APIIC Tower, Hermitage Plaza, the new Camp Nou stadium, home of FC Barcelona and 200 Greenwich Street, the second tower of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan.

- Paul Morley, music journalist, critic and author of The North (And Almost Everything In It) grew up in Reddish.

- David Carr, incorrectly believed (due to a mix-up in samples) to have been the first human to contract AIDS, was born in Reddish.

- Clifford Poole, who worked as a music educator and composer in Ontario, Canada, was born in Reddish.[119]

See also

References

Bibliography

- Astle, William (1922). Stockport Advertiser Centenary History of Stockport. Stockport: The Stockport Advertiser. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- Arrowsmith, Peter (1997). Stockport: a History. Stockport: Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. ISBN 0-905164-99-7.

- Ashmore, Owen (1975). The Industrial Archaeology of Stockport. Manchester: University of Manchester. ISBN 0-902637-17-7.

- Booker, John (1857). A history of the ancient chapels of Didsbury and Chorlton. Chetham.

- Cronin, Jill (2000). Images of England: Reddish. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-1878-5.

- Downham, W A (1922). "Chapter XIII". In Astle, William (ed.). Stockport Advertiser Centenary History of Stockport. Stockport: The Stockport Advertiser.

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, John (2003–2006) [1911]. The Victoria history of the county of Lancaster. - Lancashire. Vol.4. University of London & History of Parliament Trust.

- Hartwell, Clare; Matthew Hyde; Nikolaus Pevsner (2004). Lancashire: Manchester and the South-East. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10583-5.

Notes

- "Reddish North 2011 Census figures". Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "Reddish South Census Figures 2011". Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- Farrer and Brownbill, pp. 326–9.

- Booker, p. 197.

- Ekwall, E (1922). NS 81 The place-names of Lancashire. Manchester: Chethams. p. 30.

- Arrowsmith, p. 23.

- Mills, A D (1997). Dictionary of English Place-Names (2nd ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 285. ISBN 0-19-280074-4.

- Hartwell et al., p. 197.

- Harland, John; Wilkinson, Thomas Turner (1993) [1873]. Lancashire Legends, Traditions. Llanerch Press. pp. 26–9. ISBN 1-897853-06-8.

- Higson, John; Jeff Goldthorpe (January 2004). "The battle of Gorton" (PDF). Gorton News. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2006.

- Farrer and Brownbill, pp 275–279, footnote 1. "Out of Gore-ton and Red-ditch, with the help of the intervening Nico Ditch, popular fancy has made the story of a great battle in the neighbourhood; Harland and Wilkinson, Traditions. 26.

- Hartwell et al., p. 18.

- Downham, p. 142.

- Cronin, p. 45.

- "Houldsworth Conservation Area Character Appraisal". Stockport MBC webpages. Stockport MBC. April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- Hartwell et al., p. 230.

- Cited in many places, e.g. Downham p. 144. Archived March 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Corry, John (2006) [1825]. The history of Lancashire, Volume 1. Thomson Gale. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- Booker, p. 200, repeated verbatim by Farrer & Brownbill.

- Downham, p. 149.

- Booker, p. 201.

- Furnival and Co

- J. E. H. Andrew and Co

- Craven Brothers

- Downham.

- Astle

- Newman, Bernard (1957). One hundred years of good company. Lincoln: Ruston & Hornsby. pp. 75–6.

- Cronin, p82.

- Ashmore, pp 45, 86.

- Holden p168, Ashmore p84, Arrowsmith p258.

- Cronin p58

- "TWO COTTON MILLS TO CLOSE". The Times. The Times. 28 October 1958. p. 10.

- Ashmore p85, Cronin p79.

- Ashmore p85.

- Ashmore p27.

- "SOURCE OF RUEFUL REFLECTION". The Times. The Times. 24 March 1965. p. 5.

- "ELIMINATED TOO SOON". The Times. The Times. 19 October 1965. p. 5.

- "Now MBB spotlight will fall on Europe". Manchester Evening News. 3 August 1994.

CARADON Friedland of Reddish, the world's leading maker of doorbells and chimes ...

- "Opportunities knock for entrepreneur Richard". Manchester Evening News. Manchester Evening News. 19 December 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Stockport awarded Houldsworth honour". Manchester Evening News. Manchester Evening News. 1 November 2005. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "Houldsworth Mill: The Prince's Regeneration Trust". The Prince's Regeneration Trust. 17 October 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Houldsworth (1981)". Stockport MBC web pages. Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- "£60 m scheme to launch Reddish urban village". Manchester Online. GMG Regional Digital. 1 February 2005. Archived from the original on 23 December 2005. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "40 years ago". Stockport Express. Guardian Media Group. 10 December 2002. Archived from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- "Boddingtons' bid £1M. for R. Clarke". The Times. 8 December 1962. p. 13.

- Jones, Rhys P, ed. (1991). Viaduct and vaults: a celebration of Stockport's pubs. St Albans: CAMRA Ltd. p. 43. ISBN 1-85249-054-3.

- "History page". 3 Rivers Brewery. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- "WebCHeck". Companies House. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Edwardson, Peter (28 October 2006). "Stockport Pub Guide M-Z". Archived from the original on 16 July 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- Ordnance Survey; Jill Cronin (1994) [1904]. Old Ordnance Survey Maps: North Reddish and S W Denton. Gateshead: Alan Godfrey Maps. ISBN 0-85054-654-0.

- "Blue Plaque Winners". Stockport MBC web site. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- In the early stages of the blue plaque campaign that saw the Houldsworth WMC honoured, the council's web site mistakenly listed and described Reddish WMC. The web page was originally at www.stockport.gov.uk/content/councildemoc/council/campaigns/blueplaqueselection/reddishworkingmensclub, now removed, and stated "The club was founded by Robert Hyde Greg in 1845 as a Mechanics Institute and Library and located within the Albert Mills. It was acknowledged to be the oldest club on the Club and Institute Union Register. From 1878, it occupied part of the Albert British School until 1891, when a new building was erected on the present site."

- Scapens, Alex (29 August 2007). "Club celebrates its 150 year history". Stockport Express. M.E.N media. Retrieved 21 September 2007. Sandfold brewing, which used to be called 3 rivers.

- Farrer, William (1907). Record Society for the publication of Original Documents relating to Lancashire and Cheshire. Vol LIV. Lancashire Inquests, Extents, and Feudal Aids. Part II. The Record Society. pp. 65–6.

- Crofton, H T (1905). "Agrimensorial remains around Manchester". Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society. 23: 112–71.

- Crofton, H T (1904). NS 52 A history of Newton chapelry in the ancient parish of Manchester. Manchester: Chetham Society.

- "Reddish UD Lancashire through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project. Archived from the original on 26 July 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- Arrowsmith, p. 239. Astle, pp. 73–4. Cronin, pp. 8, 35.

- "Reddish Tn/CP Lancashire through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project. Archived from the original on 26 July 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- Astle p 49 (pdf). Archived March 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Arrowsmith p 239. Astle pp 49 Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, 77 Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, 79 Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, 94 Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine (pdf). Cronin pp 35–6.

- Astle p 80 (pdf). Archived March 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Stockport Advertiser History of Stockport, 1922–1932, being a supplement to the Advertiser centenary history 1822–1922, pp 7 Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, 18 Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine (pdf).

- "Reddish Tn/CP Lancashire through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- Green, Judith A. & Lander, S. J. (1979). "Table of population". In Harris, B. E. (ed.). A History of the county of Chester. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. p. 188. ISBN 0-19-722749-X.

In 1901 Reddish U.D. and part of Heaton Norris C.P. were transferred from Lancashire to Cheshire, and a further part of Heaton Norris was added in 1913

- "Denton and Reddish". Guardian Unlimited Politics. London: Guardian Newspapers Limited. Archived from the original on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

- "Your Councillors by Ward". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council webpages. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Booker, p. 200.

- Wilson, John Marius (1870–72). Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales. Cited at "Reddish Lancashire through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project. Retrieved 5 October 2006.

- Cronin, p. 8.

- Ashmore pp 28, 84. Cronin, pp. 7, 41.

- Cronin, pp. 7, 12.

- Ashmore, pp. 28–9

- Cronin, pp. 40–1. Hartwell et al., p. 582.

- "Stockport District Centres ANNUAL UPDATE January 2004". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. January 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- "Agora Project". Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- "AGORA". Manchester Metropolitan University Business School. Archived from the original on 4 January 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- "District Centres". Stockport MBC web site. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- Seymore, Jane (2000). "Appendix 4, Human Poverty Index for British Parliamentary Constituencies and OECD Countries". Poverty in Plenty: A Human Development Report for the UK. London: Sterling Earthscan Publications Ltd. pp. 143, 147–8, 153, 156. ISBN 978-1-85383-707-4.

- National Statistics Online Archived 11 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine, Model-Based Estimates of Income for Wards (April 01 to March 02), retrieved 14 February 2006.

- North West Selected Key Statistics, National Statistics, retrieved 14 February 2006.

- "Listed buildings in stockport" (PDF). Stockport MBC web pages. Stockport MBC. 3 February 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- "Landmark former pub in Reddish is given new lease of life by vac firm". Manchester Evening News. Manchester Evening News. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Reddish Corridor". u to us. 14 October 2004. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- Bus routes & timetables are at "GMPTE - Public Transport for Greater Manchester, UK". GMPTE. Retrieved 20 October 2006. See: 7 (Stockport-Ashton); 178 (Reddish-Wythenshawe Hospital); 203 (Stockport - Manchester); 317 (Hazel Grove-Ashton).

- Arrowsmith, p. 161.

- Ashmore, pp. 58–70.

- Butterworth, James (1827–1828). A history and description of the towns and parishes of Stockport, Ashton-under-Lyne, Mottram-Long-den-Dale and Glossop. Manchester. pp. 250, 282.

- Arrowsmith, p. 263.

- Arrowsmith, p. 160

- Arrowsmith, pp. 231–6

- Johnson, E M (2000). The Fallowfield line: an illustrated review of the Manchester Central Station line. Romiley: Foxline. pp. 3–6. ISBN 1-870119-69-X.

- Suggitt, Gordon (2004). Lost railways of Merseyside and Greater Manchester. Newbury: Countryside Books. p. 134. ISBN 1-85306-869-1.

- Hulme, Charles (1991). Rails of Manchester: a short history of the city's rail network. Manchester: John Rylands University Library of Manchester. p. 24. ISBN 0-86373-105-8.

- Johnson, E M (1997). Woodhead: Manchester London Road, Gorton, Guide Bridge, Glossop and the Longdendale Valley Pt. 1. Romiley: Foxline. p. 37. ISBN 1-870119-43-6.

- Woodward, Mark (2004). Inspection Report: Reddish Vale Technology College (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2005. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- "Department for Education and Skills / Details for Reddish Vale Technology College". EduBase. Crown copyright. 1995–2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Reddish Vale Farm". Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Reddish Vale Technology College, Reddish, Stockport, Specialist School". RVTC. 1998–2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council / Primary Schools". SMBC webpages. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Department for Education and Skills / Welcome to EduBase". EduBase. Crown copyright. 1995–2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Primary Schools (Denton and Reddish)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 1 November 2005. col. 801–804. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007.

- "£5million new Reddish school moves step closer". Stockport Express. Guardian Media Group. 7 December 2005. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Poisoned school site is a 'minefield'". Stockport Express. Guardian Media Group. 31 May 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- "Friends of Reddish Baths". Archived from the original on 2 January 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "Councillors pull plug on residents' bath takeover". Stockport Express. Guardian Media Group. 30 March 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- "Church Details - Diocese of Manchester Web Site". The Diocese of Manchester web site. The Diocese of Manchester. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "St Agnes Church, North Reddish - An Inclusive Church". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- Hartwell et al., p. 372.

- "Welcome to Christ Church". Archived from the original on 27 May 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "Church Details - Diocese of Manchester Web Site". The Diocese of Manchester web site. The Diocese of Manchester. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "St Elisabeth's". Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "Parish details (Mass times and Websites)". Salford Diocese pages. Salford Diocese. 2006. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "Parish details (Mass times and Websites)". Salford Diocese pages. Salford Diocese. 2006. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- "Church Details - Diocese of Manchester Web Site". The Diocese of Manchester web site. The Diocese of Manchester. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Edward Hubbard (1969). The Buildings of England: South Lancashire. London: Penguin. p. 372. ISBN 0-14-071036-1.

- "Welcome to Reddish Christian Fellowship". Archived from the original on 2 May 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- "Stockport - Adventist Organizational Directory". Archives&Statistics. General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 12 January 2003. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- "Clifford Poole". The Canadian Encyclopedia, by Betty Nygaard King, July 16, 2007