Redwood National and State Parks

The Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP) are a complex of one national park and three California state parks located in the United States along the coast of northern California. The combined RNSP contain 139,000 acres (560 km2), and include Redwood National Park, Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park. Located within Del Norte and Humboldt counties, the four parks protect 45 percent of all remaining coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) old-growth forests. The species is the tallest, among the oldest, and one of the most massive tree species on Earth. The parks also preserve other indigenous flora, fauna, grassland prairie, cultural resources, waterways, and 37 miles (60 km) of pristine coastline.

| Redwood National and State Parks | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

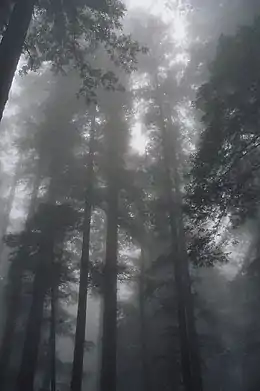

A forest of coast redwoods in fog | |

| |

| Location | Humboldt County & Del Norte County, California, US |

| Nearest city | Crescent City |

| Coordinates | 41°18′N 124°00′W |

| Area | 138,999 acres (562.51 km2)[1] |

| Established | October 2, 1968 |

| Visitors | 458,400 (in 2022)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service and California Department of Parks and Recreation |

| Website | https://www.nps.gov/redw/ |

| Criteria | Natural: (vii), (ix) |

| Reference | 134 |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th Session) |

In 1850, old-growth redwood forest covered more than 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of the California coast. The northern portion of that area was originally inhabited by Native Americans who were forced out of their land by gold seekers and timber harvesters. The enormous redwoods attracted timber harvesters to support the gold rush in more southern regions of California and the increased population from booming development in San Francisco and other places on the West Coast. After many decades of unrestricted clear-cut logging, serious efforts toward conservation began. By 1918, the work of the Save the Redwoods League, founded to preserve remaining old-growth redwoods, resulted in the establishment of Prairie Creek, Del Norte Coast, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Parks among others. The federally managed Redwood National Park was created in 1968, by which time nearly 90 percent of the original redwoods had been logged. In 1994, the National Park Service (NPS) and the California Department of Parks and Recreation (CDPR) combined Redwood National Park with the three abutting Redwoods State Parks as a single administrative unit for the purpose of cooperative forest management and stabilization of forests and watersheds.

The ecosystems of the RNSP preserve a number of threatened animal species, such as the tidewater goby, Chinook salmon, northern spotted owl, and Steller's sea lion, though the tidewater goby and the candlefish are believed to have been extirpated from the park in 1968.[3] In recognition of the rare ecosystem and cultural history found in the parks, the United Nations designated them a World Heritage Site on September 5, 1980.

History

Native Americans

Modern day Native American nations such as the Yurok, Tolowa, Karok, Chilula, and Wiyot have historical ties to the region.[4] Historian David Stannard accounts for more than thirty native nations living for millennia in northwestern California, one of the world's most diverse regions.[5] Scholar Gail L. Jenner estimates that "at least fifteen" tribes inhabited the area we now assign to the park,[6] and some groups still live within park boundaries today.

The Yurok, Chilula, and Tolowa were the most connected to the places we now call parks.[7] Based on an 1852 census, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber estimated that the Yurok population in that year was around 2,500. Historian Ed Bearss described the Yurok as the most populous in the area, estimating that there were around 55 villages.[8] Until the 1860s, the Chilula lived in the middle region of the Redwood Creek valley in close company with the redwood trees.[9] They primarily settled along Redwood Creek between the coast and Minor Creek, California, and when food was abundant they would range into and camp in the Bald Hills. Part of the Yurok reservation and two Chilula village sites (Howunakut and Noieding) are located within the contemporary boundaries of the parks.[10] The Tolowa considered their origin to be near the mouth of the Smith River,[11] and they mainly settled along it, though their territory ranged from near the Oregon border to just above the Klamath River.[12] They inhabited lands that are now part of Jedediah Smith State Park, an area which has been inhabited for about 8,500 years.[11]

The tribes harvested coast redwoods and processed them into planks, using them as building material for boats, houses, and small villages.[13] To construct buildings, the planks would be erected side by side in a narrow trench, with the upper portions bound with leather strapping and held by notches cut into the supporting roof beams. Redwood boards were used to form a shallow sloping roof.[14]

Redwoods were not just a useful resource for indigenous groups. Jenner notes that "their lives were – and are – built on more than just wood, although the redwood was the source of much of their material culture; their lives were enmeshed in the very character and fabric of the trees." Minnie Reeves, a Chilula tribal elder and religious leader, said in 1976 that the Chilula are "people from within the redwood tree".[15] Reeves elaborates that the trees are a gift from the creator as a demonstration of love: "Destroy these trees and you destroy the Creator's love. And if you destroy that which the Creator loves so much, you will eventually destroy mankind."[16] To the Yurok, the trees are sacred living beings that "stand as 'guardians' over sacred places". Indigenous people regard traditional houses made of redwood trees as "living beings" too, since, according to Bearss, "the redwood that formed its planks was itself the body of one of the Spirit Beings", which were considered, in his words, to be a "divine race who existed before humans in the redwood region and who taught people the proper way to live there".[15]

Arrival of European Americans

Prior to Jedediah Smith in 1828, no other explorer of European descent is known to have explored the interior of the Northern California coastal region. Smith and nineteen companions left San Jose, California, and explored what are now called the Trinity, Smith, and Klamath rivers, passing through coastal redwood forests and trading with Native American groups. They reached the coast near Requa, parts of which are within the parks' boundaries.[17]

The California Gold Rush of 1848 brought hundreds of thousands of Europeans and Americans to California,[18] and the discovery of gold along the Trinity River in 1850 brought many of them to the region of the parks. This quickly led to conflicts wherein native peoples were displaced, raped, enslaved, and massacred.[19] By 1895, only one third of the Yurok in one group of villages remained; by 1919, virtually all members of the Chilula tribe had either died or been assimilated into other tribes.[20] The Tolowa—whose numbers Bearss estimates at "well under 1,000" by the 1850s—had a population of about 120 in 1910,[12] having been nearly extinguished in massacres by settlers between 1853 and 1855.[21]

The miners logged redwoods for building; when this minor gold rush ended, some of them turned again to logging, cutting down the giant redwood trees.[22]

Preservation

Initially, over 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of the California and southwestern coast of Oregon were old-growth redwood forest, but by 1910, extensive logging led conservationists and concerned citizens to begin seeking ways to preserve the remaining trees, which they saw being logged at an alarming rate.[22] In 1911, U.S. Representative John E. Raker, of California, became the first politician to introduce legislation for the creation of a redwood national park. However, no further action was taken by Congress at that time.

Preservation of the redwood stands in California is considered one of the most substantial conservation contributions of the Boone and Crockett Club. The Save the Redwoods League was founded in 1918 by Boone and Crockett Club members Madison Grant, John C. Merriam, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and future member, Frederick Russell Burnham. The initial purchases of land were made by club member Stephen Mather and William Kent. In 1921, Boone and Crockett Club member John C. Phillips donated $32,000 to purchase land and create the Raynal Bolling Memorial Grove in the Humboldt Redwoods State Park.[23] This was timely as U.S. Route 101, which would soon provide nearly unfettered access to the trees, was under construction. Using matching funds provided initially by the County of Humboldt and later by the State of California, the Save the Redwoods League managed to protect areas of concentrated or multiple redwood groves and a few entire forests in the 1920s. As California created a state park system, beginning in 1927, three of the preserved redwood areas became Prairie Creek Redwoods, Del Norte Coast Redwoods, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Parks. A fourth became Humboldt Redwoods State Park, by far the largest of the individual Redwoods State Parks, but not in the Redwood National and State Parks system. Because of the high demand for lumber during World War II and the construction boom that followed in the 1950s, the creation of a national park was delayed. Efforts by the Save the Redwoods League, the Sierra Club, and the National Geographic Society to create a national park began in the early 1960s.[24] After intense lobbying of Congress, the bill creating Redwood National Park was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on October 2, 1968.

The Save the Redwoods League and other entities purchased over 100,000 acres (400 km2), which were added to existing state parks. Amidst both local support of environmentalists and opposition from local loggers and logging companies, 48,000 acres (190 km2) were added to Redwood National Park in a major expansion in 1978.[24] However, only a fifth of that land was old-growth forest, the rest having been logged. This expansion protected the watershed along Redwood Creek from being adversely affected by logging operations outside the park. The federal and state parks were administratively combined in 1994.[25]

Expansion of the national park was controversial because of the impact on the logging community and because most of the parkland was already sustainably managed by the private timber industry with the old-growth within the expanded park already protected.[26] It remains the largest purchase of private land by the federal government in history as well as the largest eminent domain action. In 1977, a 25-truck convoy featuring logging equipment crossed the country to deliver President Jimmy Carter a 9-ton peanut carved from old-growth redwood. The president refused the gift, and the Orick Peanut was returned to Orick, a logging town adjacent to the newly expanded park that saw substantial economic decline in the following decades.[27]

The United Nations designated the Redwood National and State Parks a World Heritage Site on September 5, 1980. The evaluation committee noted 50 prehistoric archaeological sites, spanning 4,500 years. It also cited ongoing research in the park by Humboldt State University researchers, among others.[28]

Park management

Redwood National Park is directly managed by the U.S. government's National Park Service (NPS) located in Crescent City, California.[29] NPS also manages about 1,400 acres (5.7 km2) of federal park land and waters that lie within the Yurok Indian Reservation.[30] The three state parks are overseen by the California Department of Parks and Recreation (CDPR). Federal and state agencies agreed to a joint general plan, and so to manage all four parks together as Redwood National and State Parks.[31]

Redwood National Park management oversees many other details aside from the redwoods and organic species that reside within the park boundaries. They also regulate areas that are off limits to motor vehicles, boats, drones, horses, pets and even bicycles. In addition, park management establishes limitations on camping, campfires, food storage and backcountry use, as well as necessary permits needed.[32]

When it opened in 1969, Redwood National Park had only six permanent employees.[33] Early park managers prioritized restoring existing structures, rehabilitating the watershed, and developing wildlife management plans.[34] Until 1980, managers assumed that the three state parks, which are contained within the boundaries of the national park, would be donated to the NPS.[30] The donation did not happen,[30] and NPS and the state signed a memorandum in 1994 governing joint management and agreeing to the name "Redwood National and State Parks".[35]

Natural resources

The Redwood National and State Parks form one of the most significant protected areas of the Northern California coastal forests ecoregion.

Coast redwood

Coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) are the tallest trees on Earth. The tallest specimen alive is 380 feet (120 m)[36] and the species has a theoretical maximum height of between 400 and 427 feet (122 and 130 m).[37] Not as long-lived as its relative Sequoia gigantea,[38] mature coast redwoods live an average of 500–700 years and a few are documented to be 2,000 years old.[39] Coast redwood is a shade tolerant conifer.[40] It has no taproot, and its roots spread into a wide lateral root system.[41] Due to a thick protective bark and high tannin content, it is highly resistant to disease.[39] As of 1990 a stand in Humboldt Redwoods State Park had the greatest biomass ever recorded.[41] Redwood trees develop enormous limbs that accumulate deep organic soils and can support tree-sized trunks growing on them.[42] Plants called epiphytes which normally grow on the forest floor grow in these soils.[43] Mats of epiphytic ferns well above ground are home to invertebrates, mollusks, earthworms, and salamanders.[44] During drought seasons, some treetops die back, but the trees do not die outright. Instead, redwoods developed lignotubers to regrow new trunks from other limbs.[45] These secondary trunks, called reiterations, also develop root systems in the accumulated soils at their bases.[45] This helps transport water to the highest reaches of the trees.[45] Redwoods prefer sheltered slopes, and thrive on moist flat ground along rivers below 1,000 feet (300 m) in elevation.[40] Coastal fog provides about 40 percent of their annual water intake.[46]

Redwoods have existed along the coast of northern California for at least 20 million years and are related to tree species that existed 160 million years ago in the Jurassic era.[46] One of three living redwood species, the coast redwood is closely related to the giant sequoia of central California, and more distantly to the dawn redwood which is indigenous to the Sichuan–Hubei region of China.[47] The current range of coast redwood is a 450-mile (720 km) long and 5-to-35-mile (8 to 56 km) wide strip along the west coast of the United States from the northern California coast north to the southern Oregon Coast.[48] It is estimated that old-growth redwood forest once covered close to 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of coastal northern California.[49] Almost half (45 percent) of the redwoods remaining in California are found in RNSP, and 96 percent of all old-growth redwoods have been logged. The parks protect 38,982 acres (157.75 km2) of old-growth forest almost equally divided between federal and state management.[39] The International Union for Conservation of Nature named the coastal redwood an endangered species in 2011.[50]

As of September 2006, the tallest tree in the park was Hyperion at 380 feet (120 m), followed by Helios at 377 feet (115 m), and Icarus at 371 feet (113 m).[36] For many years thought to be the tallest, one specimen named simply "Tall Tree" within the RNSP in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park was measured at 367.8 feet (112.1 m). "So many people have stood on the base of the tree that the ground is hard packed," said Professor Stephen C. Sillett of Humboldt State in the 1990s.[51] The top 10 feet (3.0 m) of the tree died in the 1970s, and fell off in the 1990s.[51] In 2022 after documenting damage caused by visitors to the tallest living tree, NPS announced a penalty for those who approach it of up to a $5,000 fine and six months in jail,[36] and shows visitors instead to views of other trees—views that are better than any possible view of Hyperion.[52]

Other flora

Coast redwood tends to dominate in places it likes but often can be found together with also-fast-growing coast Douglas-fir trees. Closer to the ocean, red alder grow in place of the salt-water intolerant redwood.[53] The tallest known Sitka spruce grows in the parks.[54] Sitka spruce are plentiful along the coast, better adapted to salty air than other species. Other associated trees are the tanoak, Pacific madrone, bigleaf maple, and California laurel.[55]

Huckleberry and snowberry are part of the forest understory.[55] The California rhododendron and azalea are flowering shrubs common in the parks.[55] Plants such as the sword fern and redwood sorrel are prolific.[55]

In Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, Fern Canyon is a well-known ravine 50 feet (15 m) deep,[53] with walls completely covered in ferns—California maidenhair, deer fern, California polypody, licorice fern, and western swordfern.[56] The ancestors of some of these ferns reach back 325 million years.[57]

Fauna

The ecosystems of the RNSP preserve a number of rare animal species. Numerous ecosystems exist, with seacoast, river, prairie, and densely forested zones all within the park. Over 40 species of mammals have been documented, including the black bear, coyote, cougar, bobcat, beaver, river otter, and black-tailed deer. Roosevelt elk are the most readily observed of the large mammals in the park.[58] Successful herds, brought back from the verge of extinction in the region, are now common in park areas.[58] Many smaller mammals live in the high forest canopy. Different species of bats, such as the big brown bat, and other smaller mammals including the red squirrel and northern flying squirrel spend most of their lives well above the forest floor.[59]

About half of RNSP's 28 species that are federally recognized as endangered, threatened, or candidates can be seen in the parks.[3] The bald eagle, which usually nests near a water source, is listed as a state of California endangered species.[60] The Chinook salmon, northern spotted owl, and Steller's sea lion are a few of the other animal species that are threatened.[3][61] The tidewater goby is a federally listed endangered species that lives near the Pacific coastline that were extirpated from the parks in 1968 when shoreline alterations affected the water's salinity. The candlefish soon followed in the 1970s.[62] Sea otters were extirpated in the parks at the turn of the 20th century but river otters remain.[63] Also endangered, the marbled murrelet can nest high on redwood branches.[58]

Along the coastline, California sea lions, Steller sea lions and harbor seals live near the shore and on seastacks, rocky outcroppings forming small islands just off the coast.[63] Dolphins and Pacific gray whales are occasionally seen offshore.[63] Brown pelicans and three species of cormorants are mainly found on cliffs along the coast and on seastacks, while sandpipers and three species of gulls inhabit the seacoast and inland areas.[64] Inland, freshwater-dependent birds such as the common merganser, osprey, red-tailed hawk, herons, and jays are a few of the bird species that have been documented.[64] Approximately 280 bird species, or about one third of those found in the US, have been documented within park boundaries.[64]

Reptiles like four species of sea turtle can be found offshore and sometimes on beaches.[65] Amphibians can also be found in the parks, which the gopher snake,[66] tailed frog,[67] clouded salamander,[68] and three species of newt[69] call home. Well-known detritivores, the banana slug and the yellow-spotted millipede, inhabit the parks.[70]

NPS provides safety tips for visitors who encounter wildlife such as elk, black bears, and mountain lions, as well as poison oak and ticks.[71]

Invasive species

Currently, over 200 exotic species live in the RNSP. Of these, 30 have been identified as invasive species, and 10 of the 30 are considered threats to local species and ecosystems.[72] Exotic species currently account for about a quarter of the total flora in the parks.[72] Only about one percent of plant growth in old-growth areas are of exotic species, while areas such as the Bald Hills prairies have a relative exotic cover of 50 to 75 percent.[72] Spotted knapweed and poison hemlock were both under consideration in 2015 for addition to a high priority watch list maintained by the park system.[73]

Geology

The parks are located in the most seismically active area in the country.[74] Frequent minor earthquakes in the park and offshore under the Pacific Ocean have resulted in shifting river channels, landslides, and erosion of seaside cliffs.[74] The North American, Pacific, and Gorda Plates are tectonic plates that all meet at the Mendocino Triple Junction, only 100 miles (160 km) southwest of the parks.[74] During the 1990s, more than nine magnitude 6.0 earthquakes occurred along this fault zone resulting in one death and major financial loss, and there is always potential for a major earthquake.[75] The area is the most tsunami-prone in the continental U.S., and visitors to the seacoast are told to seek higher ground immediately after any significant earthquake.[71] The park's altitude is below sea level up to 837 meters (2,746 ft) at Rodgers Peak.[28]

Both coastline and the mountains of the California Coast Ranges can be found within park boundaries.[28] The majority of the rocks in the parks are part of the Franciscan Assemblage,[28] uplifted from the ocean floor millions of years ago. These sedimentary rocks are primarily sandstone, siltstone, shale, and chert, with lesser amounts of metamorphic rocks such as greenstone.[28] Redwood Creek follows the Grogan Fault; along the west bank of the creek, schist and other metamorphic rocks can be found, while sedimentary rocks of the Franciscan Assemblage are located on the east bank.[28]

Climate

| Climate data for Redwood National and State Parks (Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park; Del Norte County) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

80 (27) |

81 (27) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

90 (32) |

78 (26) |

72 (22) |

98 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 53.4 (11.9) |

55.0 (12.8) |

56.0 (13.3) |

56.9 (13.8) |

60.7 (15.9) |

63.4 (17.4) |

65.0 (18.3) |

65.1 (18.4) |

65.2 (18.4) |

62.6 (17.0) |

56.6 (13.7) |

52.7 (11.5) |

59.4 (15.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 35.8 (2.1) |

36.5 (2.5) |

38.1 (3.4) |

39.9 (4.4) |

44.0 (6.7) |

47.6 (8.7) |

50.4 (10.2) |

50.8 (10.4) |

47.4 (8.6) |

42.9 (6.1) |

38.8 (3.8) |

35.5 (1.9) |

42.3 (5.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 18 (−8) |

19 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

27 (−3) |

24 (−4) |

33 (1) |

34 (1) |

36 (2) |

24 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

16 (−9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 12.18 (309) |

10.65 (271) |

10.31 (262) |

6.27 (159) |

3.94 (100) |

2.00 (51) |

0.37 (9.4) |

0.53 (13) |

1.21 (31) |

5.00 (127) |

11.42 (290) |

15.72 (399) |

79.60 (2,022) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.4 (1.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.1 (2.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.6 | 15.7 | 17.1 | 14.0 | 9.0 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 16.3 | 17.4 | 127.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA (normals, 1981–2010)[76] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Western Regional Climate Center (records and snowfall 1948–2006)[77] | |||||||||||||

The Redwood National and State Parks have an oceanic temperate rainforest climate, with cool-summer Mediterranean characteristics.[78] The nearby Pacific Ocean has major effects on the climate in the parks.[79] Temperatures near the coast mostly remain between 40 and 60 degrees Fahrenheit (4–15 °C) all year.[79] Redwoods tend to grow in this area of steadily temperate climate, though most grow at least a mile or two (1.5–3 km) from the coast to avoid the saltier air, and they never grow more than 50 miles (80 km) from it. In this humid coastal zone, the trees receive moisture from both heavy winter rains and persistent summer fog.[80] The presence and consistency of the summer fog is actually more important to overall health of the trees than the precipitation. This fact is born out in annual precipitation totals, which range between 25 and 122 inches (64 and 310 cm) annually, with healthy redwood forests throughout the areas of less precipitation because excessive needs for water are mitigated by the ever-present summer fog and the cooler temperatures it ensures. Snow is uncommon even on peaks above 1,500 feet (460 m),[81] but light snow mixed with rain is common during the winter months.

Parts of the parks are threatened by climate change. Increasing average temperatures have led to reduced water quality, affecting the fish and other fauna, and rising sea levels threaten to damage park structures near the coast. The redwoods benefit from higher carbon levels and are resilient against temperature changes, though the range in which they live is likely to shift along with weather patterns.[82]

Fire management

Prescribed controlled fires are part of the fire management plan, and they help to eliminate exotic species of plants and allow a more fertile and natural ecosystem. Fire is also used to protect prairie grasslands and to keep out forest encroachment, ensuring sufficient rangeland for elk and deer. The oak forest regions also benefit from controlled burns, as Douglas fir would otherwise eventually take over and decrease biodiversity. The use of fire in old-growth redwood zones reduces dead and decaying material, and lessens the mortality of larger redwoods by eliminating competing vegetation.[83] The park's fire management plan calls for monitoring all fires, weather patterns and the fuel load (dead and decaying plant material). The fuel load level is controlled by either removing material or using controlled burns.[84]

Recreation

The park has five visitor centers, where general information, maps, and souvenirs are available; some of the centers offer activities during the summer, led by the park rangers.[85] There is no entry fee for the RNSP, though some camping areas and park areas require paid passes.[86]

Since the late-2019 closure of the DeMartin Redwood Youth Hostel, a low-amenities shared lodging facility (near Klamath),[87] there are no hotels or motels within the parks' boundaries. However, nearby towns such as Klamath, Requa, and Orick provide small hotels and inns, with extensive lodging options available in the regional trading centers: Crescent City on the northern end of the park and Arcata and Eureka located to the south. The park is about 260 miles (420 km) north of San Francisco and 300 miles (480 km) south of Portland, Oregon; U.S. Route 101 passes through it from north to south. The Smith River National Recreation Area, part of the Six Rivers National Forest, is adjacent to the north end of the RNSP.

The state parks have four frontcountry campgrounds which can be accessed by vehicle and used for a fee; the parks' website suggests making a reservation. These are at Mill Creek campground in Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park and Jedediah Smith campground in Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, which together have 251 campsites; the Elk Prairie campground in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, which has 75; and the Gold Bluffs Beach campground which has 26. Other nearby parks and recreation areas have additional camping options.[88]

Hiking is the only way to reach the seven backcountry camping areas, the use of which requires a permit. Camping is only allowed in designated sites, except on gravel bars along Redwood Creek that allow for dispersed camping. Proper food storage to minimize encounters with bears is strongly enforced, and hikers and backpackers are required to take out any trash they generate.[89]

Almost 200 miles (320 km) of hiking trails exist in the parks. Throughout the year, trails are often wet and hikers need to be well prepared for rainy weather and consult information centers for updates on trail conditions. Some temporary footbridges are removed during the rainy season, as they would be destroyed by high streams.[89]

Horseback riding and mountain biking are allowed on certain trails.[90] Kayaking is permitted, with ranger-led kayak tours offered during the summer.[91] Kayakers and canoeists frequently travel the Smith River,[92] which is the longest undammed river remaining in California.[91] Visitors can fish for salmon and trout in the Smith and Klamath rivers, and the beach areas offer opportunities to catch smelt and perch. A California sport fishing license is required to fish any of the rivers and streams.[93]

See also

- Redwoods State Parks:

Notes

- "NPS listing of acreage". National Park Service. September 30, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- "Annual Visitation Report by Years: 2012 to 2022". National Park Service. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- "Threatened and Endangered Species". National Park Service. March 3, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- Bearss 1982, Section 1A. The Yurok.

- Stannard 1993, pp. 21–22.

- Jenner 2016, p. 20.

- Jenner 2016, pp. 20–21.

- Bearss 1982, Section 1A. The Yurok. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- "The Chilula: Bald Hills People" (PDF). Park Newspaper (Visitor's Guide). National Park Service. 2002. p. 2. Retrieved August 11, 2023 – via National Park Service History eLibrary.

- Bearss 1982, Section 1C. The Chilula Retrieved July 29, 2023..

- Jenner 2016, p. 23.

- Bearss 1982, Section 1B. The Tolowa Retrieved October 15, 2023..

- Castillo, Edward D. (1998). "Short Overview of California Indian History". California Native American Heritage Commission. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- Nabokov & Easton 1990.

- Jenner 2016, pp. VII–VIII.

- Jenner 2016, p. 35.

- Jenner 2016, pp. 41–42.

- Jenner 2016, p. 44.

- "American Indians". Area History. National Park Service. February 5, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- "The Chilula". The Indians of the Redwoods. National Park Service. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Jenner 2016, p. 54.

- "Logging". Area History. National Park Service. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Sheldon 1925, p. 198.

- Schrepfer, Susan R. (1983). The Fight to Save the Redwoods: A History of Environmental Reform, 1917-1978. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 130–185. ISBN 978-0-299-08850-7.

- "Redwood National and State Parks". UNESCO. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Associated California Loggers (1977). Enough is Enough (Film).

- Rosalsky, Greg (June 21, 2022). "The tale of a distressed American town on the doorstep of a natural paradise". National Public Radio.

- "Redwood National Park (includes Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park)" (PDF). Protected Areas and World Heritage. United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- "Directions". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- "Redwood National and State Parks: General Management Plan, General Plan (Summary)" (PDF). State of California. p. 6. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- "Redwood National and State Parks: General Management Plan, General Plan (Summary)" (PDF). State of California. p. 3. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- "Superintendent's Compendium". National Park Service. May 17, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Jenner 2016, p. 167.

- Jenner 2016, pp. 167–168.

- Jenner 2016, p. 168.

- Kim, Juliana (August 1, 2022). "People who want to visit the world's tallest living tree now risk a $5,000 fine". NPR. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- Koch et al. 2004.

- Shirley 1947, Section 11.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. August 17, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Olson, Jr., Roy & Walters 1990, p. 543.

- Olson, Jr., Roy & Walters 1990, p. 547.

- Sillett et al. 2018.

- Spickler et al. 2006, p. 16.

- Spickler et al. 2006, pp. 17, 18, 22.

- Sillett & Van Pelt 2007.

- "About The Trees". National Park Service. February 28, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- "The Three Redwoods" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- Griffith, Randy Scott (1992). "Sequoia sempervirens. In: Fire Effects Information System". Rocky Mountain Research Station: US Forest Service, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- "The Struggle For Redwood National Park". Redwood History Basic Data. National Park Service. January 15, 2004. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Farjon, Aljos; Schmid, Rudolf (2013). "Sequoia sempervirens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T34051A2841558. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T34051A2841558.en. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- Carle, Janet. "Tracking the Tallest Tree". California State Park Rangers Association. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- "Should I Hike to Hyperion?". National Park Service. November 29, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- Urness, Zach (June 4, 2014). "World's best redwood hike not all about big trees". Statesman Journal. Gannett.

- Jenner 2016, p. 5.

- "Plants". National Park Service. March 4, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- "Fern Viewing Areas Not On National Forests". US Forest Service. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- "Trails - South of the Klamath River". National Park Service. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- "Redwood National and State Parks Visitor Guide" (PDF). National Park Service. 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- "Redwood National and State Parks Visitor Guide" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- "Bald Eagles in California". State of California. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Animals". National Park Service. April 17, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- "Tidewater Goby and Candlefish". National Park Service. November 24, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- "Marine Mammals". National Park Service. November 21, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Birds". National Park Service. February 1, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Coastal Redwood National and State Parks" (PDF). Save the Redwoods League. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Gopher snake". National Park Service. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Tailed Frog". National Park Service. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Clouded Salamander". National Park Service. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Showers activate waterfalls, newts, and fungi". Save the Redwoods League. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "Banana Slug & Millipede". National Park Service. November 20, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- "Your Safety". National Park Service. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- "Resource Management and Science - exotic plant management". National Park Service. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- "exotic plant species list". National Park Service. February 28, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- "Natural Features & Ecosystems". National Park Service. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- Oppenheimer, David (December 17, 2007). "Mendocino Triple Junction Offshore Northern California". A Policy for Rapid Mobilization of USGS OBS (RMOBS). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- "CA Klamath". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- "Klamath, California". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- Jenner 2016, p. 3.

- "Weather". National Park Service. October 13, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- Jenner 2016, p. 6.

- "Park Geology". Geology Fieldnotes. National Park Service. January 1, 2005. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- "Redwoods and Climate Change". National Park Service. October 25, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- "Environmental Factors: Living with Fire". National Park Service. January 24, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- "Redwood National and State Parks Fire Management Plan 2010" (pdf). National Park Service. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- "Visitor Centers". National Park Service. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- "Fees & Passes". National Park Service. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- "Former Hostel Building To Be Removed". Redwood National and State Parks (U.S. National Park Service).

- "Campgrounds". National Park Service. December 8, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- "Backcountry: Designated Campsites". National Park Service. October 30, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- "Outdoor Activities". National Park Service. October 22, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- "Kayaking". National Park Service. November 24, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "Jedediah Smith Redwoods Day Use Area". National Park Service. January 28, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "Fishing". National Park Service. September 30, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

References

Works cited

Books

- Bearss, Edwin C. (March 1982) [September 1, 1969]. Redwood National Park: History Basic Data. National Park Service. OCLC 22209484. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- Silvics of North America (Agriculture Handbook #654). Vol. 1. Conifers. Russell M. Burns & Barbara H. Honkala, tech. coords. Southern Research Station: United States Department of Agriculture: US Forest Service. 1990.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

- Olson, Jr., David F.; Roy, Douglass F.; Walters, Gerald A. (1990). "Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don) Endl.". Silvics of North America. pp. 541–551.

- Jenner, Gail (2016). Historic Redwood National and State Parks. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4930-1809-3.

- Nabokov, Peter; Easton, Robert (October 25, 1990). Native American Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506665-4.

- Redwood: A Guide to Redwood National and State Parks, California. Interior Dept., National Park Service, Division of Publications. 1997. ISBN 978-0-912627-61-8.

- Sheldon, Charles (1925). Grinnell, George Bird (ed.). Hunting and Conservation: The Book of the Boone and Crockett Club. Yale University Press. OCLC 1631773.

- Shirley, James Clifford (1947). The Redwoods of Coast and Sierra. University of California Press. OCLC 1455702 – via National Park Service.

- Stannard, David E. (November 18, 1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983890-5.

Journal articles

- Koch, George W.; Sillett, Stephen C.; Jennings, Gregory M.; Davis, Stephen D. (2004). "The limits to tree height". Nature. 428 (6985): 851–854. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..851K. doi:10.1038/nature02417. PMID 15103376. S2CID 11846291.

- Sillett, Stephen C.; Antoine, Marie E.; Campbell-Spickler, Jim; Carroll, Allyson L.; Coonen, Ethan J.; Kramer, Russell D.; Scarla, Kalia H. (2018). "Manipulating tree crown structure to promote old-growth characteristics in second-growth redwood forest canopies". Forest Ecology and Management. 417: 77–89. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2018.02.036. ISSN 0378-1127.

- Spickler, James C.; Sillett, Stephen C.; Marks, Sharyn B.; Welsh, Jr., Hartwell H. (2006). "Evidence of a new niche for a North American salamander: Aneides vagrans residing in the canopy of old-growth redwood forest" (PDF). Herpetological Conservation and Biology. 1 (1): 16–26.

- Sillett, Stephen C.; Van Pelt, Robert (2007). "Trunk Reiteration Promotes Epiphytes and Water Storage in an Old-Growth Redwood Forest Canopy". Ecological Monographs. 77 (3): 335–59. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

External links

- Official website of Redwood National Park

- Official website of Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park

- Official website of Humboldt Redwoods State Park

- Official website of Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park

- Humboldt Redwoods Project at Humboldt State University

- Chronology: Establishment of the Redwood National Park at Forest History Society

- Inventory of the Redwood National Park Collection, 1926–1980, at Forest History Society