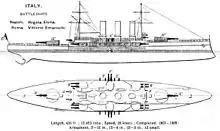

Regina Elena-class battleship

The Regina Elena class was a group of four pre-dreadnought battleships built for the Italian Regia Marina between 1901 and 1908. The class comprised four ships: Regina Elena, the lead ship, Vittorio Emanuele, Roma, and Napoli. Designed by Vittorio Cuniberti, they were armed with a main battery of two 12-inch (305 mm) guns and twelve 8 in (203 mm) guns, and were capable of a top speed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph). They were the fastest battleships in the world at the time of their commissioning, faster even than the British turbine-powered HMS Dreadnought.

Regina Elena on 17 May 1907, about four months before she was commissioned. | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders | Regina Elena class |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Regina Margherita class |

| Succeeded by | Dante Alighieri |

| Built | 1901–1908 |

| In commission | 1907–1927 |

| Completed | 4 |

| Scrapped | 4 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 13,807 long tons (14,029 t) |

| Length | 144.6 m (474 ft) |

| Beam | 22.4 m (73 ft) |

| Draft | 8.58 m (28.1 ft) |

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) |

| Range | 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 742–764 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

The ships saw service during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912 with the Ottoman Empire. They frequently supported Italian ground forces during the campaigns in North Africa and the islands of the eastern Mediterranean Sea. They served during World War I, in which Italy participated from 1915 to 1918, but they saw no combat as a result of the cautious policies adopted by the Italian and Austro-Hungarian navies. All four ships were discarded between 1923 and 1926 and broken up for scrap.

Design

Starting in 1899, Vittorio Cuniberti began design work on a warship armed with a uniform battery of twelve 8-inch (203 mm) guns, armored with 6 in (150 mm) thick belt armor, and capable of a top speed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph), on a displacement of 8,000 long tons (8,100 t). This proved to be the genesis of Cuniberti's later designs, which culminated in the British all-big-gun HMS Dreadnought. When the 1899 design project was not accepted, Cuniberti turned his attention to a new design requirement for a 13,000-long-ton (13,210 t) battleship faster than all British and French battleships and stronger than the armored cruisers fielded by both navies. This resulted in a modified version of his earlier design, what came to be the Regina Elena class. The first two vessels—Regina Elena and Vittorio Emanuele—were ordered for the 1901 fiscal year, and the final pair—Roma and Napoli—were authorized the following year.[1][2] Due to their high speed, they are sometimes referred to as "forerunner[s] of the battlecruiser."[3]

General characteristics and machinery

The ships of the Regina Elena class were 132.6 meters (435 ft) long at the waterline and 144.6 m (474 ft) long overall. They had a beam of 22.4 m (73 ft) and a draft of 7.91 to 8.58 m (26.0 to 28.1 ft). They displaced 12,550 to 12,658 long tons (12,751 to 12,861 t) at normal loading and up to 13,771 to 13,914 long tons (13,992 to 14,137 t) at full combat load. The ships had a crew of 742–764 officers and enlisted men. The ships were initially fitted with two masts, but after refits early in their careers, Regina Elena's and Napoli's foremasts were removed. The ships had a slightly inverted bow and a long forecastle deck that extended past the main mast.[4]

The battleships' propulsion system consisted of two vertical four-cylinder triple expansion engines that drove a pair of screw propellers. Steam for the engines was provided by twenty-eight coal-fired Belleville boilers in the first two ships, and twenty-eight Babcock & Wilcox boilers in the last two, split between three boiler rooms. The boilers were trunked into three tall funnels. The ships' propulsion system was rated at 19,299 to 21,968 indicated horsepower (14,391 to 16,382 kW) and provided a top speed in excess of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph); Napoli, the fastest member of the class, reached 22.15 knots (41.02 km/h; 25.49 mph) on her speed trials. The ships had a range of approximately 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). At the time of their completion, they were the fastest battleships in the world, faster even than the steam turbine-powered HMS Dreadnought.[4][5]

Armament and armor

The Regina Elenas were armed with a main battery of two 305 mm (12 in) 40-caliber guns placed in two single gun turrets, one forward and one aft. The turrets were placed well clear of the superstructure, giving them a wide arc of fire, close to 300 degrees of rotation. Electric power was used for training and elevation of the turrets and ammunition handling. The lighter main battery, compared to other pre-dreadnought type battleships that typically carried twice as many heavy guns, was criticized by some observers, but Dr. Philip Alger, writing in Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute noted that "it should be borne in mind that a pair of guns in a turret do not make twice as good shooting as a single gun," and that given the limited displacement of the design, it "was the wisest choice that could be made."[6] Fire control for the guns was provided by Barr and Stroud rangefinders mounted on the conning tower. The ammunition magazines were fitted with refrigeration systems to minimize the risk of accidental explosions.[7]

The ships were also equipped with a secondary battery of twelve 203 mm (8 in) 45-cal. guns in six twin turrets amidships,[4] which also used electrical operation. The central turrets were placed a deck higher than the others to permit them firing directly ahead and astern.[8] Close-range defense against torpedo boats was provided by a battery of sixteen 76 mm (3 in) 40-cal. guns, though Roma and Napoli both had an additional eight guns of this caliber. All four ships were also equipped with two 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes placed in the hull below the waterline.[4]

The ships were protected with Krupp cemented steel manufactured in Terni. The main belt was 250 mm (9.8 in) thick amidships, reduced to 152 mm (6 in) abreast of the main battery turrets, and 102 mm (4 in) thick at the bow and stern. The deck was 38 mm (1.5 in) thick. The conning tower was protected by 254 mm (10 in) of armor plating. The main battery guns had 203 mm thick plating, and the secondary turrets had 152 mm thick sides.[4][5]

Ships of the class

| Name | Builder[4] | Laid down[4] | Launched[4] | Completed[4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regina Elena | Arsenale di La Spezia | 27 March 1901 | 19 June 1904 | 11 September 1907 |

| Vittorio Emanuele | Regio Cantiere di Castellammare di Stabia | 18 September 1901 | 12 October 1904 | 1 August 1908 |

| Roma | Arsenale di La Spezia | 20 September 1903 | 21 April 1907 | 17 December 1908 |

| Napoli | Regio Cantiere di Castellammare di Stabia | 21 October 1903 | 10 September 1905 | 1 September 1908 |

Service histories

.jpg.webp)

The four ships of the Regina Elena class served in the active duty squadron after their commissioning through 1911 and participated in the peacetime routine of fleet training.[9] On 29 September 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire, starting the Italo-Turkish War. The four ships saw action during the war in the 1st Division of the 1st Squadron. They participated in the operations off North Africa in the first months of the war, including escorting the crossing of the Italian expeditionary army sent to conquer Cyrenaica. Later in the war, they took part in the seizure of Rhodes and the Dodecanese.[10]

Italy initially remained neutral during World War I, but by 1915, had been convinced by the Triple Entente to enter the war against Germany and Austria-Hungary. Both the Italians and Austro-Hungarians adopted a cautious fleet policy in the confined waters of the Adriatic Sea, and so the four Regina Elena-class battleships did not see action.[11] They spent the war rotating between the naval bases at Taranto, Brindisi, and Valona.[12] After the end of the war, the ships of the class were included amongst the battleships that Italy could keep in service (by the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty[13]), but they were retained only for a few years. Between February 1923 and September 1926, all four ships were stricken from the naval register and broken up for scrap.[4]

Notes

- Fraccaroli, pp. 336, 344.

- Hore, p. 81.

- Marshall, p. 228.

- Fraccaroli, p. 344.

- Alger, p. 345.

- Alger, p. 344.

- Alger, pp. 345–346.

- Alger, p. A344.

- Brassey, p. 56.

- Beehler, pp. 6, 9, 27–29, 74–76.

- Halpern 1995, pp. 140–142.

- Halpern 2004, p. 20.

- "Conference on the Limitation of Armament". ibiblio - The Public's Library and Digital Archive. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

References

- Alger, Philip R. "Professional Notes". Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. 34 (125): 333–379.

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1911). "Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 55–62.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1979). "Italy". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Annapolis: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 334–359. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2004). The Battle of the Otranto Straights: Controlling the Gateway to the Adriatic in World War I. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34379-6.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- Marshall, Chris, ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of Ships: The History and Specifications of Over 1200 Ships. Enderby: Blitz Editions. ISBN 1-85605-288-5.

Further reading

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0105-3.

External links

- Regina Elena Marina Militare website